Abstract

Background: The symptom checklist SCL-27-plus is a short, multidimensional screening instrument for mental health problems. It contains five scales on current symptoms: depressive, vegetative, agoraphobic, and sociophobic symptoms and pain; a global severity index (GSI-27); a lifetime assessment for depressive symptoms; and a screening question for suicidality.

Method: A reformulated version of screening items constituted a survey of n=374 students. Therefore, a total of 76 items was formulated and presented to the students within a questionnaire booklet, that could be filled out at home.

Results: All scales of the SCL-27-plus showed good to satisfactory reliability (i.e. .90 ≥ Cronbach’s a ≥ .70). The distributions of the scales were less skewed than in older versions of the symptom checklists and scale inter-correlations were lower. The scale “symptoms of mistrust” could not be retained.

Conclusion: The SCL-27-plus demonstrates a clear improvement over the SCL-27. Test-statistical properties were improved. In addition, the supplementation by a lifetime scale for depression and a screener for suicidality shall help the clinician as well as the epidemiologist.

Keywords: SCL-27-plus, screening for mental health problems, reliability, suicidality

Abstract

Hintergrund: Die Symptomcheckliste-27-plus ist ein kurzes, mehrdimensionales Screening-Instrument für psychische Probleme. Sie enthält fünf Skalen zu aktuellen Symptomen (depressive, vegetative, agoraphobische und soziophobische Symptome, Schmerz), einen globalen Schwere-Index, eine Skala zur Lebenszeit-Erfassung von Depression und ein Item zu Suizidalität.

Methode: Reformulierte Screening-Items wurden in einer Stichprobe von n=374 Studenten vorgelegt. Dazu erhielten die Studenten 985 reformulierte Items innerhalb eines Fragebogenheftes, das sie zuhause ausfüllen konnten.

Ergebnisse: Alle Skalen der SCL-27-plus zeigen gute bis befriedigende Reliabilitäten (.90 ≥ Cronbach’s a ≥ .70) . Die Skalen sind weniger schief verteilt als in älteren Versionen der SCL und die Skaleninterkorrelationen liegen niedriger. Die Skala „Symptome von Misstrauen“ konnte nicht erhalten werden.

Schlussfolgerung: Die SCL-27-plus stellt eine klare Verbesserung der SCL-27 dar. Die teststatistischen Eigenschaften wurden verbessert. Die zusätzliche Erfassung von Lebenszeit-Depression und Suizidalität soll dem Kliniker wie dem Epidemiologen zugute kommen.

Introduction

The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R: [1]), including its short forms (for an overview, see [2], [3]) probably constitutes the most widely applied psychometric questionnaire. The full-length version assesses nine distinct psychiatric dimensions and a global severity index. At least in research, the frequency of the use of the full length version has decreased considerably since various studies reported severe psychometric shortcomings of the SCL-90-R (e.g. [4], [5]. Most researchers today use one of the short versions (e.g. [6], [7], [8]). Some of the short forms retain only the global severity index, others try to retain a multidimensional structure [2].

We developed a short form comprising only 27 out of the 90 original items [SCL-27: [4], [9], [10]). The SCL-27 is a selection of those items from the SCL-90-R that could be summarised into distinct scales. It has six sub scales, i.e. “depressive symptoms”, “dysthymic symptoms”, “vegetative symptoms” , “agoraphobic symptoms”, “symptoms of social phobia” and “symptoms of mistrust”. The SCL-27 demonstrated considerably better psychometric properties than the SCL-90-R, but not all problems inherent in the SCL were solved in a satisfactory way.

The wording of the items does not always fulfill the criteria set for modern psychological tests [11]. Some items are not precisely formulated, others contains an “or” or relative clauses. In addition, some items sound antiquated, i.e. do not mirror the language people talk and think today. Maybe this is one reason why two psychometric problems remained in basically all existing short versions of the SCL. Scales are extremely skewed and if various dimensions are retained the inter-correlations of the sub scales were sometimes close to the coefficients for reliability.

Due to this reasons, a new questionnaire was developed, the symptom checklist-27-plus. All items were translated into a modern language, short and precise wording of the items was minded. Symptoms as formulated in DSM-IV [12] and ICD-10 [13] were added. Five instead of four items were generated for each dimension, what makes it possible to estimate a score even for probands who leave two items per subscale missing. A subscale on pain was added. The subscale for “dysthymic symptoms” was deleted because it had not found much interest beside depressive symptoms. The subscale for symptoms of mistrust had to be deleted because it could not be separated from symptoms of social phobia.

For the depressive symptoms scale, the point prevalence estimate was supplemented with a lifetime estimate. This is one reason why the new version carries a “plus” in its name. The second reason for adding the “plus” was that a screening question on suicidality was included in the SCL-27-plus. The purpose of this addition was to help the clinician avoid overlooking a patient’s potentially fatal feeling of desperation. Congruent with DSM-IV [12] and ICD-10 [13], the time frame for depressive symptoms was extended to two weeks, the introduction for the other scales was changed from “one week” to “in general”. The latter was done because anxiety and vegetative symptoms are not expected to show much variation. High stability over time in the SCL-90-R indicates that he state concept may not be fully right for the SCL [14].

The present paper introduces the SCL-27-plus and presents similarities and differences between the new SCL-27-plus and the old SCL-27. We not only looked at item means and standard deviations, but analysed the structure of the scales as well. Ancovas were performed to test for age and gender effects. The SCL-27-plus is available via internet [15].

Design

Sample

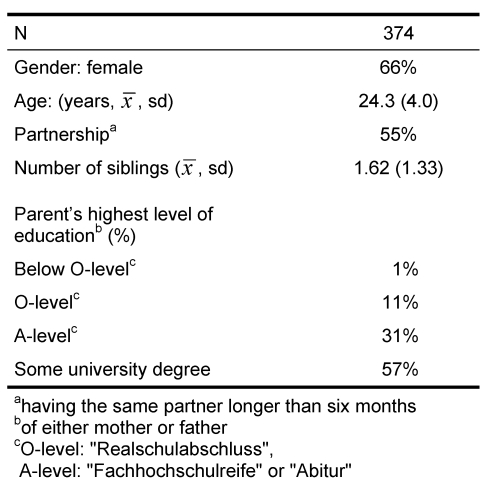

Participants were students of social sciences and medicine in one of their first six semesters. They were informed that the survey was being conducted to examine various circumstances of their lives and well-being. They also were told that new questionnaires were to be examined as well as that cross-national surveys were going to be made. At the end of various lectures, a total of about 640 students were asked to take part in the study. The students were handed a booklet with questionnaires and asked to take it home, fill it out alone, and return it at the next lecture. Later filing was accepted until the end of the semester. To assure anonymity, an envelope addressed to JH was distributed with the booklet for return of the questionnaires. Students were informed that the time needed to fill out the booklet was about 45 minutes. Because one part of the questionnaire booklet contained sensitive items on abuse, students received a guarantee that their data would be handled with all care necessary to retain their anonymity. Hence, neither name nor date of birth was revealed. Returned questionnaires were left in the closed envelopes, which were mixed in a box; data entry did not begin until 100 questionnaires had been turned in. A total of 376 out of the 640 students returned a filled-out booklet in time. Participation was voluntary for all students and unpaid for one part (n=141) of the sample; another part (n=235) received compensation of about € 5,- when they returned the closed envelope (differences between the two subsamples are the subject of a different paper). Two students in the subsample that was paid returned an empty questionnaire in the envelope and were counted as no return. Hence, we achieved a participation rate of about 59%. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Düsseldorf. Characteristics of the sample are summarised in Table 1 (Tab. 1).

Table 1. Sample characteristics .

Procedures

The SCL-27-plus was the second questionnaire in a booklet that consisted of about 30 pages and approximately 430 items. It covered the content of the SCL-27 through various formulations of about 76 items and was supplemented by additional symptoms regarded as important by clinicians. Out of all 76 items, the 27 presenting with highest concordant and lowest discriminant correlations were selected. The old version of the SCL-27 followed as the third questionnaire in the booklet. Because it made no sense to ask for current suicidality in an anonymous survey, the question was turned into one on lifetime suicidality. In order to minimise typing errors, double data entry was accomplished via different persons using a special computer program. The items for the point estimate had a range from “0” to “4”. For the scales vegetative, agoraphobic, and sociophobic symptoms and pain, the instruction was changed to mark how often the symptoms generally occurred; a value of “0” stood for never, “1” stood for seldom, “2” for sometimes, “3” for often, and “4” for very often. For current depressive symptoms, a time frame of two weeks was set; the answers indicated the number of days during the last two weeks that the individual experienced the respective symptom. A value of “0” stood for never, “1” stood for 1-2 days, “2” for 3-7 days, “3” for 8-12 days, and “4” for 13-14 days. The items for lifetime depression were to be answered with “No” or “Yes” to indicate whether there ever was a time period of two weeks or longer during which a particular symptom was present for at least half of the days. Some individuals who had more than one depressive phase in their lifetime may become confused by a more detailed answering mode. Subscore scales of the SCL-27-plus were calculated as the mean of their respective items. Two items of each scale (in GSI, five items) were allowed to be missing; in that case the mean of the other items was used to estimate the values of the missing items.

The first step of the analysis was to compare item and subscore means between the old and the new version. In a second step, convergent and discriminant item correlations were displayed for the new version. (Data regarding the old version already have been displayed in various previous articles.) The alpha level for all statistical tests was set to .05 (two-tailed). Calculations were performed using ITAMIS [16], R 2.6.0 [17], SPSS 6.13 [18], and STATA 9.0 [19].

Results

Acceptability

Most students (90%) filled out all items of the SCL-27-plus without leaving a single one unanswered. About six percent of the students left exactly one item unanswered, and the remaining four percent between two and ten items. This outcome yielded a missing rate of about 8.5 per 1000 items. On the lifetime scale for depression, 96.5% of the students filled out all five items, 1.5% left one item unanswered, about 1% left all five items unanswered, and the remaining group was in-between. Here, the missing rate was 16.5 per 1000 items.

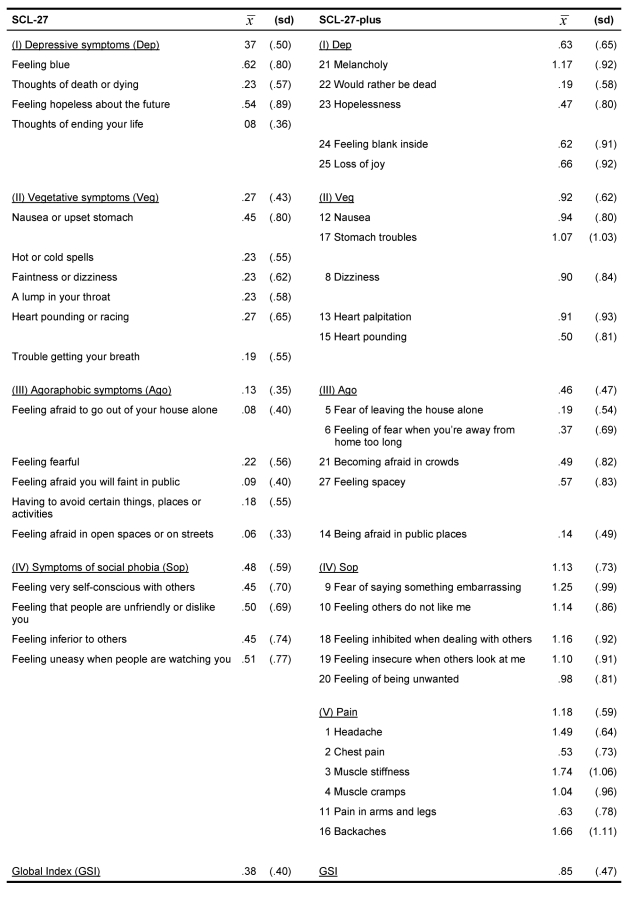

Comparison of means

The new scales displayed higher means than the old ones throughout, the tests for depressive, vegetative, agoraphobic and sociophobic symptoms were all significant at p<.001. Depressive symptoms, for example, presented with a mean of  =.37 in the old form compared with

=.37 in the old form compared with  =.63 in the new one. Larger differences were observed for vegetative symptoms (

=.63 in the new one. Larger differences were observed for vegetative symptoms (  =.27 old vs.

=.27 old vs.  =.92 new) and symptoms of social phobia (

=.92 new) and symptoms of social phobia (  =.48 old vs.

=.48 old vs.  =1.13 new). Still, the lowest mean was observed for agoraphobic symptoms (

=1.13 new). Still, the lowest mean was observed for agoraphobic symptoms (  =.13 old vs.

=.13 old vs.  =.36 new). The new scale on pain had a mean of

=.36 new). The new scale on pain had a mean of  =1.18. Symptoms of mistrust could not be separated from symptoms of social phobia, so the former scale was excluded from the questionnaire. The global index showed a value of

=1.18. Symptoms of mistrust could not be separated from symptoms of social phobia, so the former scale was excluded from the questionnaire. The global index showed a value of  =.85 compared with

=.85 compared with  =.38 for the old form. Except for the scale “vegetative symptoms”, which has a higher mean in women than in men, there are no significant sex differences (Table 2 (Tab. 2)).

=.38 for the old form. Except for the scale “vegetative symptoms”, which has a higher mean in women than in men, there are no significant sex differences (Table 2 (Tab. 2)).

Table 2. Scale and item means and standard deviations .

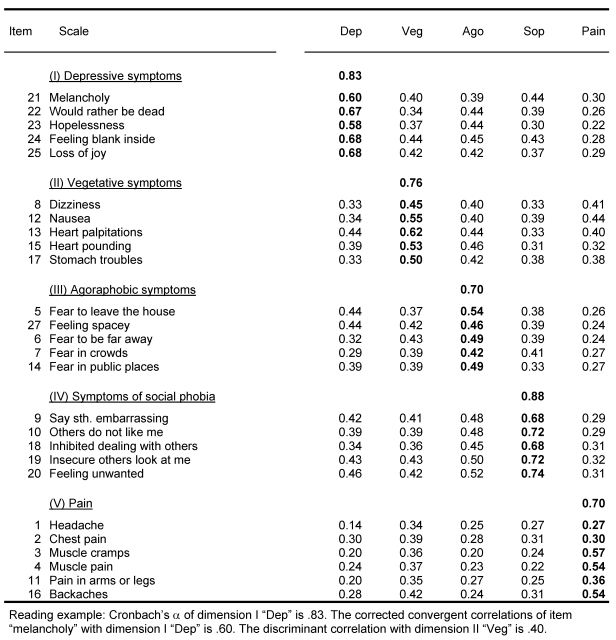

Reliabilities, item-scale assignments, and scale correlations

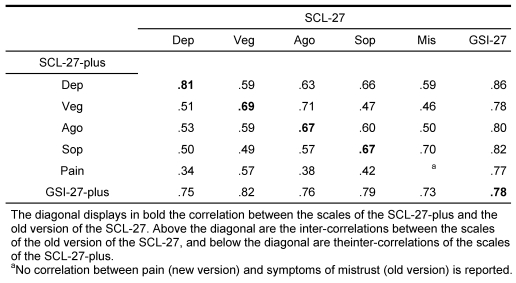

Reliabilities of the new scales were satisfactory for all scales. Depressive symptoms presented with a value of α=.83 (current), vegetative symptoms had an internal consistency of α=.76, agoraphobic symptoms showed a value of α=.70, symptoms of social phobia presented with α=.88, and pain showed a value of α=.70. The global index presented with α=.90. All item assignments to their subscales were optimal except for two items: Headaches and chest pain had higher affiliations with the scale “vegetative symptoms” than with the scale “pain” (Table 3 (Tab. 3)). The scale intercorrelations are lower in the SCL-27-plus than in the old version, the median is .50.

Table 3. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and item correlations.

Lifetime assessment of depression and suicidality

The scale for lifetime depression showed a mean of  =.39 (sd=.35, α=.83). The item “melancholy” was positively answered by 61% of the students, the item “blank inside” by 36%, “would rather be dead” by 19%, “hopelessness” by 37% and “loss of joy” by 41%. A total of 151 students reported to have had one or more depressive phases during their lifetime, with a median of 3.0 phases. The maximum number that was reported was 99, followed by 50, then 25. We first considered excluding the largest number, but an exploration of the rest of the questionnaire revealed severe symptoms throughout, along with many and severe adverse experiences in childhood and adulthood. So we decided to retain the value, which probably signified that this student had had many depressive phases, too many to count. A lifetime history of suicide attempts was reported by 2% of the sample, a suicide plan by 3%, serious thoughts about suicide by 18%, and never to have had a serious thought about suicide by 74%. Three percent chose not to answer the question (Table 3 (Tab. 3), Table 4 (Tab. 4)).

=.39 (sd=.35, α=.83). The item “melancholy” was positively answered by 61% of the students, the item “blank inside” by 36%, “would rather be dead” by 19%, “hopelessness” by 37% and “loss of joy” by 41%. A total of 151 students reported to have had one or more depressive phases during their lifetime, with a median of 3.0 phases. The maximum number that was reported was 99, followed by 50, then 25. We first considered excluding the largest number, but an exploration of the rest of the questionnaire revealed severe symptoms throughout, along with many and severe adverse experiences in childhood and adulthood. So we decided to retain the value, which probably signified that this student had had many depressive phases, too many to count. A lifetime history of suicide attempts was reported by 2% of the sample, a suicide plan by 3%, serious thoughts about suicide by 18%, and never to have had a serious thought about suicide by 74%. Three percent chose not to answer the question (Table 3 (Tab. 3), Table 4 (Tab. 4)).

Table 4. Dimension intercorrelations (Pearson).

Discussion

In this first study on students, the SCL-27-plus presents as a questionnaire that has promising psychometric properties. The acceptability of the questionnaire was good, with 8 to 9 missing responses per 1000 items. The lifetime depressive symptom scale showed a slightly higher missing rate, but this result could be expected because not everybody can remember previous depressive episodes. Scale means were considerably higher than in the old version. All items except two (headaches and chest pain) fulfilled the criterion of having a higher concordant than any discriminant correlation. However, both definitively constitute some forms of pain; if the correlation with the vegetative symptoms scale is higher than that with other forms of pain, additional surveys should demonstrate the same result. If that turns out to be the case, this item should be replaced by another form of pain. Reliabilities of the scales were satisfactory, even though pain and agoraphobic symptoms were borderline. Disappointing were the relatively high inter-correlations of the scales: A median of .50 was higher than expected. However, the old version of the SCL-27 also displayed higher inter-correlations in this sample than were observed in previous samples. One explanation for this result could be that some students, bored by the large number of items that asked about similar symptoms, decided to mark “does not apply” without reading the questions carefully. Previous research on the old version of the SCL-27 demonstrated that students displayed some specific characteristics not seen in other samples [20]. Major changes to the questionnaire should await a second run in a non-student sample and with a reduced number of items.

Somewhat surprising was the result that few items the clinicians suggested could be incorporated into the SCL-27-plus. Only to the scale depressive symptoms two items could be added, i.e. “empty inside” and “loss of joy”. No other item on the list passed the statistical criterion of having a high loading on exactly one subscale. There were items in the pool, such as “having problems with writing when others watch you” for symptoms of social phobia and “early awakening” for depressive symptoms in the current version, from which we expected some contributions, but either they did not show any significant contribution to building a scale or they were non-specific, i.e. contributed to more than one scale.

The correlations between the old scales and the new ones of the SCL-27-plus were essentially congruent but not identical. The highest values were observed for depressive symptoms and the global index; correlations in the range of .80 indicated that the scales captured almost identical constructs. Correlations in the range of .67 for the other scales were substantially lower. It should be taken into consideration that the items, the answering mode, and the instructions all were changed. Therefore, the similarity between the old and the new form is considerable. Nevertheless, the SCL-27-plus should not be taken as a one-by-one substitute for the SCL-27 in research, in particular since scale means differ considerably for the two questionnaires. Whether these changes produce a better measuring instrument is a challenge for the future.

Not very surprising was the lack of gender effects except for the scale “vegetative symptoms”. Similar results, based on students as well as representative samples, were observed previously in the SCL-27 by Hardt et al. [8]. This lack of gender effects stands in strong contrast to results of studies found in the literature that used measures other than the SCL-27. At least with respect to anxiety and depression, women show higher prevalences than men throughout the literature [21], [22], [23]. At present, the question remains open as to whether there is a general trend that gender differences in symptom checklists vanish over time or whether a specific effect of the SCL-27 will become apparent.

Our study has the following limitations: (1) The present survey is based on students, a group that is not representative of the general population, as the comparison between the German student sample and German representative surveys demonstrated [20]. In addition, no data on clinical samples are available up to now. (2) No validation data are available as of now. It will be necessary to combine independent screenings with subsequent standard diagnostic procedures to determine whether the SCL-27-plus has validity.

Given the limitations stated above, the study permits the following conclusions: The new symptom checklist-27-plus displays better psychometric properties than the old version of the SCL-27, which was based on original items of the SCL-90-R. Scale means are higher, leading to less-skewed distributions, internal consistencies are better and scale intercorrelations are lower.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank 374 students who filled out the 30-page questionnaire voluntarily. Some were totally unpaid; others, who were paid, were honest enough to return a filled-out questionnaire instead of an unanswered one in the closed envelope.

This work was supported, in part, by the Koehler-Stiftung, Essen, Germany.

References

- 1.Derogatis LR, Cleary PA. Confirmation of the dimensional structure of the SCL-90-R: a study in construct validation. J Clin Psychol. 1977;33:981–989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardt J, Brähler E. Symptomchecklisten bei Patienten mit chronischen Schmerzen: Ein Überblick. Schmerz. 2007;21:7–14. doi: 10.1007/s00482-006-0512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Recklitis CJ, Parsons SK, Shih MC, Mertens A, Robison LL, Zeltzer L. Factor structure of the brief symptom inventory--18 in adult survivors of childhood cancer: results from the childhood cancer survivor study. Psychol Assess. 2006;18(1):22–32. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardt J, Gerbershagen HU, Franke P. The symptom check-list, SCL-90-R: its use and characteristics in chronic pain patients. Eur J Pain. 2000;4(2):137–148. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2000.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cyr JJ, McKenna-Foley JM, Peacock E. Factor structure of the SCL-90-R: is there one? J Pers Assess. 1985;49(6):571–578. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4906_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaghofer R, Brähler E. Konstruktion und Teststatistische Überprüfung einer Kurzform der SCL-90-R. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2000;50:109. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen CS, Drescher KD, Moos RH, Finney JW, Murphy RT, Gusman F. Six- and ten-item indexes of psychological distress based on the Symptom Checklist-90. Assessment. 2000;7(2):103–111. doi: 10.1177/107319110000700201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardt J, Egle UT, Brähler E. Die Symptom-Checkliste 27 in Deutschland: Unterschiede in zwei Repräsentativbefragungen der Jahre 1996 und 2003. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2006;56(7):276–284. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-932577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardt J, Gerbershagen HU. Cross-validation of the SCL-27: a short psychometric screening instrument for chronic pain patients. Eur J Pain. 2001;5(2):187–197. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardt J, Egle UT, Kappis B, Hessel A, Brähler E. Die Symptom-Checkliste SCL-27: Ergebnisse einer deutschen Repräsentativbefragung. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2004;54(5):214–223. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-814786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babbie ER. The practice of social research. 7. ed. Belmont: Wadsworth; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth edition (DSM-IV) Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dilling H, Mombour W, Schmidt MH. Internationale Klassifikation psychischer Störungen. ICD-10 Kapitel V (F) Bern: Huber; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klaghofer R, Brähler E. Testbesprechung: Die Symptom-Ckeckliste von Derogatis (SCL-90-R). Deutsche Version von G. H. Franke (1995) Diagnostica. 2002;48:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardt J. Screening 4 you. Essenheim: Jochen Hardt GbR; 2008. Available form: http://www.screening4you.de/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohr HU. ITAMIS. Ein benutzerorientiertes Fortran-Programm zur Test- und Fragebogenanalyse. München: Sozialwiss. Institut der Bundeswehr; 1978. (Berichte aus dem Sozialwissenschaftlichen Institut der Bundeswehr; 6). [Google Scholar]

- 17.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.SPSSInc. Chicago: Illinois; 1995. SPSS V 6.1.3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. College Station, Texas: Stata Corporation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardt J, Dragan M, Kappis B. The SCL-27 in Poland and Germany. In prep. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Wittchen HU, Zhao S, Abelson JM, Abelson JL, Kessler RC. Reliability and procedural validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R phobic disorders. Psychol Med. 1996;26(6):1169–1177. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer C, Rumpf HJ, Hapke U, Dilling H, John U. Lebenszeitprävalenzen psychischer Störungen in der erwachsenen Allgemeinbevölkerung. Ergebnisse der TACOS-Studie. Nervenarzt. 2000;71(7):535–542. doi: 10.1007/s001150050623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]