Germany has a long record of pro-tobacco industry activities and weak tobacco control policies.1–3 In contrast, during the Nazi era in the 1930s and 1940s, Germany promoted smoke-free public places, advertising restrictions and epidemiology linking smoking to lung cancer, infertility and heart disease.4–7 Although the Nazi approach to tobacco control was ambivalent and complex, often building on pre-existing policies and with poor enforcement,8, 9 the association with the Nazis has been widely suggested as one reason for Germany’s modern weakness on tobacco control.10–12 Although Proctor cautioned against the oversimplistic interpretation of his work in The Nazi War on Cancer5 and emphasised that the introduction of tobacco control measures by the Nazis did not make tobacco control inherently fascist,4 the tobacco industry and its front groups abused and distorted history to condemn tobacco control measures as Nazi policies and its advocates as “health fascists.”8

Plans to introduce smoke-free environments in several German states by January 2008 fuelled an extensive public debate, including cover articles in the major national news magazines Der Spiegel13 and Der Stern.14 Libertarian pro-tobacco activists started using “Nazi” rhetoric to discredit journalists and public health experts.10, 15, 16 Analogies with Nazi symbols, including the use of the yellow Star of David on a pro-smoking T-shirt (fig 1) and in a TV news broadcast, were used to liken the treatment of smokers to the stigmatisation and discrimination of Jews under the Nazis.17–19 Against the background of Germany’s history, these accusations are particularly charged.

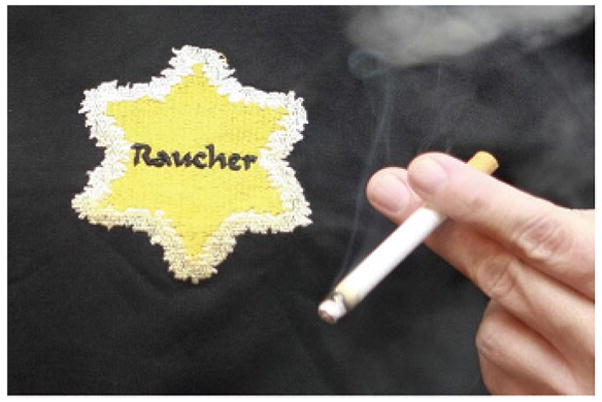

Figure 1.

T-shirt offered by a German event-marketing company in December 2007 depicting the word “smoker” (“Raucher”) in the yellow Star of David, a symbol used to stigmatise Jews during the Third Reich.17 The T-shirt, which attempted to compare the “persecution” of smokers, under smoke-free legislation, to that of Jews under the Nazis, was removed from the company’s website after public outrage.

Members of the German subsidiary of the US smokers’ rights organisation Fight Ordinances and Restrictions to Control and Eliminate Smoking (FORCES), Netzwerk Rauchen—Forces Germany eV, discussed suing a German tobacco control champion and head of the German WHO Collaborating Center for Tobacco Control, alleging “Volksverhetzung” (Agitation of the People), an accusation typically directed against neo-Nazis.15 Under German law incitement of hatred against a minority is punishable with up to five years in prison.(Strafgesetzbuch, Section 130).20

The tobacco industry and smokers’ rights groups21–24 have evoked the rhetoric and symbolism of Nazi Germany to describe public health authorities and advocates as oppressors who discriminate against smokers since at least the late 1960s. Although “Nazism” and “fascism” are not synonymous, they are often seen by the public as being the same, and were probably conflated in their use against tobacco control to evoke the same negative feelings and reactions. In the past Germany has been spared such rhetoric, probably because of fears of upsetting a tobacco industry friendly government in an environment sensitive to Nazi comparisons.25 This article traces how the tobacco industry developed and promoted Nazi and health fascism rhetoric for decades around the world.

METHODS

Between August and December 2007, we searched the tobacco industry documents made available as a result of litigation in the United States (www.legacy.library.ucsf.edu, bat.library.ucsf.edu and tobaccodocuments.org/). Initial search terms included “Nazi”, “fascism” and “health fascism” in several spellings, followed by standard snowball techniques.26 To assess the public debate we also searched for comments and articles on “health fascism AND tobacco” and “Nazi AND tobacco” on the internet. Secondary source materials included online blogs of major magazines and newspapers and open discussion fora of smokers’ rights groups (FOREST, www.forestonline.org, FORCES, www.forces.org).

RESULTS

Nazism appears: the 1960s cancer debate

After the 1964 US Surgeon General’s report27 linked smoking and cancer, the Tobacco Institute (TI), the US tobacco companies’ political and public relations arm, worked to undermine the credibility of researchers supporting this link.28 In 1967, the president of the Tiderock Corporation, one of the TI’s public relations agencies,29 published an article in Esquire magazine that the TI widely distributed to the media30–32 comparing non-smokers and tobacco control measures to Hitler and the Nazi regulations: “Start thinking about the non-smokers that you know. Well, round and round and round we smokers go—and things, today, look black indeed. Mao Tse-tung wishes to legislate thought. Adolph Hitler wished to legislate race. Anthony Comstock wished to legislate sex. Volstead wished to legislate sobriety. And Big Brother, now, wishes to legislate our habits …. We have laws which penalise discriminating in job against a man for his race, creed or color—but the health agencies are now issuing a bulletin stating that they will hire only non-smokers [emphasis in original]”.33

This rhetoric continued: a 1977 memo to the TI chairman from its vice-president compared the anti-smoking campaign plans of the American Cancer Society (ACS) to General von Runstedt’s nearly victorious counteroffensive in the second world war: “Like the 1944 Nazi blitzkrieg in the European Theatre, the new ACS drive appears to have both limited tactical objectives and larger strategic goals”.34

Fighting smoke-free air in the 1970s

The modern movement for restrictions on smoking in workplaces and public places started in the United States in the 1970s.35 In 1978 and 1980 the tobacco industry defeated efforts to pass laws requiring non-smoking sections by popular vote.36 In 1980 the industry-funded opposition campaign “Californians against regulatory excess” sent direct mail campaign materials to California voters headlined “You’re under arrest!” arguing, with regard to enforcement of the proposed law by the Health Department, “If you’re like me, you conjured up scenes from Nazi Germany where no one was safe, and where children turned their parents in to the authorities”.37

Building an intellectual frame against “health fascism”: the 1980s

At the urging of US tobacco company RJ Reynolds, in 1978 the multinational tobacco companies came together under their International Committee on Smoking Issues to commission “third party” social science academics to develop arguments to maintain the social acceptability of smoking and undermine the credibility of public health arguments, initially through its Social Costs/Social Values project and later, in the 1990s, through Associates for Research in the Science of Enjoyment (ARISE).38–40 These third parties rarely disclosed the nature of their relationships to the industry.

In a speech at the TI’s Winter Meeting in 1980, a syndicated columnist and television news commentator compared the 1964 US Surgeon General’s report to the Nazi propaganda against German and European Jews before the second world war, then continued, “having been victims since 1964, and even longer, of violent verbal propaganda abuse it is clearly possible that in the future, businessmen will become the victims of actual violence”.41 In 1991, reacting to calls for regulations based on smoking-attributable health costs, R Tollison and R Wagner, two members of the industry’s Social Costs Economist Network,42 published the book The Economics of Smoking: Getting It Right,43 arguing that “fascism technically refers to a form of state socialism where the government ‘manages’ the economy by making most or all important decisions for individuals (usually for some supposedly ‘higher purpose’) without actually nationalizing all property. The anti-smoking lobby advocates a form of ‘health fascism,’ in which Health—irrespective of the desires, goals, and plans of individuals—is touted as the only true aim of government policy”.43 As part of the industry’s effort to fight advertising restrictions, industry consultant and marketing professor Jean Boddwyn44–50 publicly argued that bans “raise serious concerns about ‘health fascism,’ censorship and behavior control by governments”.51

In 1988, the chairman and chief executive officer of Philip Morris Companies gave a speech at the Virginia Foundation for Independent Colleges in which he argued, “if fascism comes to America, it will come in the form of a health campaign … But it may be that it’s not such a long step from cigarettes to red meat and fast food, to nuclear power plants, to fried chicken, to sitting on your porch Saturday morning instead of joining the joggers”.52

In the United Kingdom the “health fascism” accusations were spearheaded by the campaign director of the tobacco industry-funded front group FOREST,24 a former employee of the influential Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), a think-tank co-financed by BAT since 1963.53 After the retirement of the FOREST founder and chairman in 1989, he wrote an internal strategy discussion paper that highlighted the appeal of the “health fascism” argument and argued that the only way that the right to smoke could be preserved would be to link it up “with the broader libertarian critique of ‘health fascism’ and the paternalism and authoritarianism of the medical establishment”.54 Two years later, FOREST published a report on the “The Historical Origins of Health Fascism,” in which a senior lecturer in history at Manchester Metropolitan University, explained how health fascism originated in the 19th century from the Victorian vaccination debate and the English social hygiene and eugenics movement.55 In the foreword former FOREST chairman Lord Harris of High Cross, head and founder of the IEA, and director of The Times (London), linked the treatment of smokers to the persecutions under the Nazis, arguing that “after all, the German Fascists are chiefly remembered for imprisoning, even killing, people with whom they disagreed, while those busily persecuting smokers stop well short of such penalties […] in many other respects there are striking similarities” [emphasis in original].55

Also in 1991, a public relations consultant to RJ Reynolds reported opposing the political correctness movement in his monthly report and suggested identifying and, when possible, “building alliances with academics who oppose the New Fascism”.56 The recruitment of third-party allies among academics in social sciences continued; Walter Williams, professor of economics at George Mason University and chair of the industry-funded 1997 Social Costs Forum, published pro-industry op-eds criticising the science behind smoke-free legislation in the Washington Times and the New York Tribune,57 in which he stated that “some of the world’s most barbarous acts, from slavery to genocide, have been facilitated by bogus science … The Food and Drug Administration’s Dr David Kessler, along with Rep Henry Waxman and Environmental Protection Agency head Carol Browner, are modern-day leaders of that ugly scheme. Don’t get me wrong; I’m not equating them to Hitler. But what distinguishes them is a matter of degree but not kind”.58 The same language has been used by influential physicians and epidemiologists with deep seated anti-authoritarian sentiments, such as the former regular Lancet contributor, tobacco industry consultant and “very keen and active member of ARISE” Petr Skrabanek,59–62 in his critique on “lifestylism”63 and “coercive healthism”,64 as well as ARISE-participant Bruce Charlton65 in “How Hitler tried to stub out smoking”, in which he compared the health promotion focus in the UK Health of the Nation strategy66 to the propaganda used by the Nazis.67

Playing the Nazi card to fight smoke-free environments around the world: the 1990s

During a demonstration against the UK National No Smoking Day, in 1992, FOREST supporters dressed in Nazi SS uniforms thanked England’s secretary of state for health for “continuing the good work of his predecessors in Nazi Germany”.68 FOREST explained the background of “health fascism” to the media and highlighted how the “various anti-food, anti-drink, and anti-lots-of-other-things groups” mirror the tactics of the anti-smokers.68 According to FOREST, the focus on health fascism “evoked a particularly interesting result from the media”: while the “die-hard anti-smoking journalists” mocked and ignored it, others realised that it was a growing phenomenon in British society.68

In response to growing pressure to limit smoking in Australia in 1993, executives from Philip Morris Australia suggested to the chief executive officer of Philip Morris International that Philip Morris “exploit the extremism, what has been described as the ‘Liberal Fascism’ of public interest groups who seek to eliminate smoking” and that “undermining the support for these groups [would be] a platform for the industry’s long term strategies”.69

The same year, despite polling Philip Morris had conducted in 198970 that showed stronger support for smoking restrictions in some European countries than in the United States, Philip Morris Corporate Affairs Europe suggested in their “Smoking Restrictions 3 Year Plan” to “pitch US practices as ‘extremist,’ indicative of intolerance, risk aversion and health fascism (for example, via ARISE)”, as one of their media targets.71 Confronted by an increasing number of draft smoke-free laws, Philip Morris Corporate Affairs launched its pan-European Advocacy Campaign “Where will they draw the line?”72 in 1995 to convince opinion leaders that smoking restrictions would not be supported in Europe.72 The aim was to frame the smokers as victims, as described in the October 1994 market research report: “What is clever about the campaign idea is that it makes the smoker the victim, whose rights need protecting, rather than the non-smoker who needs protecting from the smoker”.72 The $2.9 million advertising campaign targeted European and national legislators and civil servants and consisted of a letter to employees and two different sets of advertisements, “Pythagoras”, “attacking excessive and over-complicated legislation” and “Map”, “dramatising the dangers of the way things are going”25 in major pan-European and national print media throughout the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Greece, Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Ireland, Portugal and Greece.

The Philip Morris “map” ads (fig 2) explicitly recalled the Third Reich’s Jewish ghettos to argue that “excessive government regulation serves only to marginalize the millions who choose to smoke, causing unnecessary tension and division between smokers and non-smokers”.73 The demarcation of small “smoking sections” on city maps placed near the traditional Jewish quarters and the headlines (for example, “Where will they draw the line?” or “Do we want to create another ghetto?” as used in the Italian [“Vogliamo creare un altro Ghetto?”] and Portuguese [“Será que queremos criar um novo gueto?”] versions) explicitly recall the introduction of Jewish ghettos by the Nazis.72, 74

Figure 2.

The advertisement “Where will they draw the line?” was part of Philip Morris’s 1995 pan-European Advocacy Campaign.72 The demarcation of a small “smoking section” on a city map and the header “Vogliamo creare un altro Ghetto?” (Do we want another ghetto?) resembles the location of the Jewish ghetto during the Third Reich. The advertisements were placed in pan-European and local press in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Belgium, Luxembourg, Portugal and Greece.25 In some countries, Philip Morris opted out of the national implementation and only ran the campaign through pan-European media, in Italy because of a changing political environment, in The Netherlands because of colliding national campaigns and in Germany because of fears of upsetting a tobacco friendly government.

DISCUSSION

As early as the 1970s, the transnational tobacco companies already worked on a set of programmes using third party social science academics to construct an alternative cultural repertoire to halt the decline in social acceptability of smoking on global level.40 Besides the political advocacy by the tobacco industry through advertisements, (secretly) commissioned reports and op-eds in the media, industry-supported front groups directly attacked tobacco control initiatives with Nazi rhetoric, either to fight the introduction of new legislation or to discredit and ridicule tobacco control advocates. FORCES, a smokers’ rights organisation, uses similar strategies, as their tactics include “constantly linking anti-tobacco activists either to fascism/Nazism/communism or to some sort of criminal conspiracy against smokers and those people sympathetic towards FORCES’ causes”.75 (Unlike earlier “smokers’ rights” groups where information in tobacco industry documents demonstrates often undisclosed funding and management by the tobacco industry, the documents are silent on FORCES.23, 24, 76–78) As of December 2007, the FORCES archives portal (http://www.forces.org/Archive/) documented this endeavour with 85 online newspaper articles or commentaries including the word “Nazi”, 61 including “fascism”, 31 including “Hitler” and 23 including “Gestapo” (out of a total of 3724 articles on the tobacco debate).79 As such, the tobacco industry’s efforts to popularise the images and rhetoric of Nazism have successfully penetrated the popular media, including sources with no identifiable ties to the tobacco industry80–87 (fig 3, 88). Nazi imagery is also appearing in the new media, such as www.youtube.com, a potentially fruitful social networking site for tobacco marketers.89 Between October and December 2007, this website published 19 short videos using extensive Nazi imagery to attack and ridicule tobacco control interventions, including the Irish smoke-free legislation, and organisations like Action on Smoking and Health (fig 4).

Figure 3.

A cover article on “The Dictatorship of the Non-smokers”,88 published in the popular left-wing political magazine Veintitres in Argentina in 2003 in the context of a new administration with a ministry of health that developed a national tobacco control programme.96 Symbols combining cigarettes and swastikas are also used in other publications, mainly referring to Nicotine Nazis.97

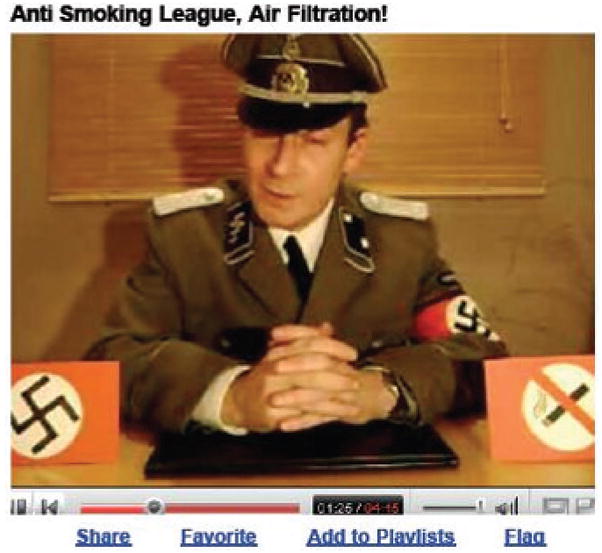

Figure 4.

The self-described propaganda minister of the fictional “Anti Smoking League.” ridicules tobacco control interventions and organisations in 19 short movie-clips on www.youtube.com. In most clips he is wearing Nazi uniform and showing swastika and non-smoking sign flags on his desk. Some movies end with links to www.forces.org and www.freedom2choose.info. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2X-PUT1WGRM, accessed 25 November 2007.)

CONCLUSION

Nazi and health fascism rhetoric has been used and promoted for decades by the tobacco industry around the world. Against the background of Proctor’s suggestion that the use of Nazi rhetoric would increase with stronger tobacco control efforts,5 the current use in Germany is neither new nor a purely German phenomenon, but probably a sign of increasing strength of Germany’s tobacco control movement. The use of Nazi and health fascism rhetoric can be regarded as part of an institutionalised practice of the tobacco industry and its front groups to discredit tobacco control activities and prevent the introduction of effective policies. “Playing the Nazi card” is an established strategy developed first in the United States and the United Kingdom, then widely used around the world, so far, predominantly outside countries with a Nazi or fascist history. This imagery is now simply being applied in Germany.

The tobacco industry is far from abandoning this strategy. Capitalising on fears of terrorist attacks in the Western world, this rhetoric is increasingly receiving a new focus, as more and more articles aim at the “Antismoking Ayatollahs” and the “theocracy of the Tobacco Taliban,” especially in the British Isles.90–95 The tobacco control community should identify and monitor the use of extremist imagery and rhetoric by the tobacco industry and its front groups, to unveil their strategies and counter their attacks on effective tobacco control and its advocates. It remains to be unveiled if the Tobacco Taliban will one day replace the Nicotine Nazi. In the meantime, such rhetoric should not deter public health advocates (and the media) from educating the public about the adverse effects of tobacco use and secondhand smoke.

What this paper adds

Following the introduction of smoke-free legislation in Germany and based on the false premise of similarities with Nazi policies, national public health leaders and media sympathetic to tobacco control were accused of being “health Nazis” or “health fascists”.

Historically accurate or not, the tobacco industry has drawn connections between tobacco control and authoritarianism, evoking the rhetoric and symbolism of Nazi Germany. The tobacco industry has used and promoted Nazi and health fascism rhetoric in the United States and United Kingdom and around the world for decades and successfully penetrated the popular media, including sources with no identifiable ties to the tobacco industry. Identification and monitoring of the use of extremist imagery and rhetoric are crucial to counter this strategy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ernesto Sebrie, Daniel Cortese, Yogi Hendlin and Sarah Sullivan for helpful comments on this work.

Both authors developed the research idea and designed the study. NS collected the industry document and drafted the manuscript, which was revised in collaboration with SG. Both authors approve the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grants CA-113710 and CA-87472). The funding agency played no part in the conduct of the research or in the preparation or revision of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Bornhauser A, McCarthy J, Glantz SA. German tobacco industry’s successful efforts to maintain scientific and political respectability to prevent regulation of secondhand smoke. Tob Control. 2006;15:e1. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuman M, Bitton A, Glantz S. Tobacco industry strategies for influencing European community tobacco advertising legislation. Lancet. 2002;359:1323–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmore A, Nolte E, McKee M, et al. Continuing influence of tobacco industry in Germany. Lancet. 2002;360:1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11262-1. author reply 1255–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Proctor RN. The anti-tobacco campaign of the Nazis: a little known aspect of public health in Germany, 1933–45. BMJ. 1996;313:1450–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7070.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Proctor RN. The Nazi war on cancer. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proctor RN. Hitler and the anti-smoking movement in the time of national socialism. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2000;112:641–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Micozzi MS. The Nazi war on cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:380–1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachinger E, McKee M. Tobacco policies in Austria during the Third Reich. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1033–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachinger E, McKee M, Gilmore A. Tobacco policies in Nazi Germany: not as simple as it seems. Public Health. 2008;122:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackenbach JP. Odol, autobahne and a non-smoking fuehrer: reflections on the innocence of public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:537–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith GD, Strobele SA, Egger M. Smoking and health promotion in Nazi Germany. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994;48:220–3. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.3.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.British American Tobacco. Smoking all over the world. 2000 2 Jul; Bates No 324540688-324540720. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/pxl55a99.

- 13.Evers M. Das ende der toleranz. Der Spiegel. 2006;24:64–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Götting M. Raucher—die verlierer der nation. Der Stern. 2007;(34) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Netzwerk Rauchen—Forces Germany eV. Raucher forum [smoker forum]. [Blog] 2007 (accessed 28 August 2007). Available from http://www.forenhoster.com/cgi-bin/yabbserver/foren/F_1858/YaBB.cgi?board=News;action=display;num=1185971256.

- 16.Der Stern. Stigmatisierte raucher—zigaretten sind droge der unterschicht [stigmatized smokers—cigarettes are the drug of the lower class]. [website] (accessed 20 August 2007). Available from http://www.stern.de/politik/panorama/595398.html?id=595398&ks=12&rendermode=comment=comments.

- 17.ast/AP/dpa. [accessed 3 March 2008];“rauchershirt” mit judenstern erlaubt. 2008 14 January; Available from http://www.focus.de/politik/deutschland/urteil_aid_233425.html.

- 18.ast/AP/dpa. [accessed 3 March 2008];Raucher-t-shirt löst empörung aus. 2008 14 January; Available from http://www.focus.de/politik/deutschland/judenstern_aid_233185.html.

- 19.ddp. [accessed 3 March 2008];Linke kritisiert mdr wegen umgang mit symbolik der judenverfolgung. 2008 3 January; Available from http://de.news.yahoo.com/ddp/20080103/ten-linke-kritisiert-mdr-wegen-umgang-mi-e3d3a04_1.html.

- 20.Federal Ministries of Justice. Criminal code (strafgestzbuch, stgb) IUSCOMP, The Comparative Law Society; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samuels B, Glantz SA. The politics of local tobacco control. JAMA. 1991;266:2110–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardador MT, Hazan AR, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry smokers’ rights publications: a content analysis. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1212–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.9.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stauber J, Rampton S. Toxic sludge is good for you. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith EA, Malone RE. ‘We will speak as the smoker’: the tobacco industry’s smokers’ rights groups. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17:306–13. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philip Morris., editor. Review of the pan-European advocacy campaign. 1995 Sep; Bates No 2045745556/5585. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wns57d00.

- 26.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control. 2000;9:334–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Department of Health Education and Welfare. Smoking and health: report of the advisory comittee to the Surgeon General of the public health service. Washington, DC: US Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cummings KM, Brown A, O’Connor R. The cigarette controversy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1070–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glantz SA, Slade J, Bero LA, et al. The cigarette papers. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loomis D, Bates T. Possible tobacco institute campaigns. Tobacco Institute; 27 Nov, 1967. Bates No TIFL0534335/4336. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hmw02f00. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blalock JV. Brown & Williamson; 17 Apr, 1967. Bates No 690014126/4127. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kex93f00. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kloepfer WJ. Reynolds RJ, editor. Attached is your copy of the Tobacco Institute’s statement of the industry’s view of the cigarette controversy. 1969 14 Jan; Bates No 508330037. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dvv93d00.

- 33.Reeves RT. Tobacco Institute; 29 Nov, 1967. Bates No TIMN0070482. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wsv92f00. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panzer F. Position paper on target 5. Brown & Williamson; 1 Feb, 1977. Bates No 670309567/9568. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kwj30f00. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glantz SA. Achieving a smokefree society. Circulation. 1987;76:746–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glantz SA, Balbach ED. Tobacco war: inside the California battles. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergland. ‘You’re under arrest’ (or ‘sign this ticket’). Sep 1980. Lorillard. Bates No 03623894/3901. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jdn71e00.

- 38.Hartogh JM. Philip Morris., editor. Telex international committee on smoking issues—ICOSI. 1978 17 Oct; Bates No 2501024613. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yqz19e00.

- 39.Philip Morris. The role and purpose of ICOSI. 1978 17 Jul; Bates No 2501024148/4149. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ltz19e00.

- 40.Landman A, Cortese D, Glantz S. Tobacco industry sociological programs to influence public beliefs about smoking. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:970–81. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.John JS. The new terrorism: the cancer crusade, and the political corruption of science. Tobacco Institute; 29 Feb, 1980. Bates No TIMN0091973/1990. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hdq92f00. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tobacco Institute. Chilcote SD., Jr Reynolds RJ, editor. “Social costs” activities. 1988 16 Mar; Bates No 506644070/4073. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fzv44d00.

- 43.Tollison RD, Wagner RE. The economics of smoking: getting it right. Tobacco Institute; 5 Feb, 1991. Bates No TITX0036852/7159. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/usx32f00. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chilcote SJ. 5 May 1987. Lorillard. Bates No 91831389/1393. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aqm50e00.

- 45.Boddewyn J, King T. Philip Morris, editor. Infotab workshop. In defense of advertising. Reports from discussion groups. Environmental tobacco smoke. 1987 13 Oct; Bates No 2500082180/2201. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eod42e00.

- 46.Reynolds RJ, editor. Tobacco Institute. FYI. In hearings this week on Capitol Hill, experts testified in opposition to the proposed ban on tobacco advertising and promotion. 1987 Dec; Bates No 506643114/3116. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xwv44d00.

- 47.Boddewyn J. Tobacco Institute; Dec, 1987. Bates No TIMN0318020. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ohu52f00. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boddewyn J. Philip Morris., editor. 1996 15 Jan; Bates No 2063734349. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vtc38d00.

- 49.Carter P. Reynolds RJ, editor. Boddewyn article for Journal of Advertising and ‘93 (930000) update on ad bans paper. 1994 7 Jan; Bates No 512709127. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ohd11d00.

- 50.Slavitt J. Philip Morris., editor. Boddewyn study. 1992 04 Aug; Bates No 2065448915A. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uap94a00.

- 51.Boddewyn JJ. Philip Morris., editor. Tobacco-advertising bans and smoking: the defective connection. 1992 Bates No 2503000815/0840. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/laq19e00.

- 52.Maxwell H. Philip Morris., editor. Choices at the bottom line: corporations, colleges and ethics. 1988 30 Jul; Bates No 2021197495/7518. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pkl46e00.

- 53.Weait JGB Limited BAT Industries. Note from JGB Weait regarding external affairs advisory committee. British American Tobacco; 1 Apr, 1980. Bates No 201033228-201033229. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/yxs20a99. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tame CR. Reynolds RJ, editor. FOREST’s future strategy: a discussion. 1989 Apr; Bates No 507652779/2785. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tvs28c00.

- 55.Davies S. The historical origins of health fascism. [accessed 13 September 2007];Report. 1991 http://www.forces.org/articles/forest/fascism.htm.

- 56.Schmidt JR. Weekly report. Louisiana. 18 Apr 1991. RJ Reynolds. Bates No 507698323/8324. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vyz14d00.

- 57.Tobacco Institute. Communications efforts October 1988. 1988 Oct; Bates No TIMN0379714/9717. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sfx42f00.

- 58.Williams W. Philip Morris., editor. Bogus tobacco science leads us into tyranny. 1994 6 Nov; Bates No 2046093989. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/npq57d00.

- 59.Dyer C. Tobacco company set up network of sympathetic scientists. BMJ. 1998;316:1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith V BM. Philip Morris., editor. 1992 3 Feb; Bates No 2023592952/2955. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/adz02a00.

- 61.Clucas RF. Philip Morris., editor. Statement 037. 1992 Bates No 2023592190/2196. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ysj53e00.

- 62.Reynolds RJ, editor. ARISE, Association for Research into the Science of Enjoyment. 1997 Bates No 520029233/9283. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hxr01d00.

- 63.Skrabanek P. Philip Morris., editor. What’s wrong with our lifestyle? Petr Skrabanek compares the old art of living with the new technique of lifestyle. 1991 3 Nov; Bates No 2028391797/1800. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/snk56e00.

- 64.Skrabanek P. The death of humane medicine and the rise of coercive healthism. Dublin: St Edmundsbury Press Ltd; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith EA. ‘It’s interesting how few people die from smoking’: tobacco industry efforts to minimize risk and discredit health promotion. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17:162–70. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Department of Health. Health of the nation: a strategy for health in England. London: HMSO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Charlton B. Philip Morris., editor. How Hitler tried to stub out smoking. 1994 11 Jul; Bates No 2050154078/4116. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uli26e00.

- 68.FOREST. Free choice, newsletter of FOREST freedom organisation for the right to enjoy smoking tobacco. British American Tobacco; May, 1992. Bates No 502559445-502559453. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/ump02a99. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Australia PM. Philip Morris., editor. 2rf presentation to WH Webb. 1993 27 May; Bates No 2504200013/0035. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jfn32e00.

- 70.Philip Morris., editor. Tobacco issues 890000 how today’s smokers & non-smokers in Europe feel about smoking issues. 1989 Bates No 2028391441/1515. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zwb24e00.

- 71.Philip Morris, editor. Philip Morris Corporate Affairs Europe. Smoking restrictions 3 year plan 1994–1996. 1993 Nov; Bates No 2025497317/7351. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hmd34e00.

- 72.Philip Morris Corporate Affairs. Philip Morris., editor. Pan-European advocacy campaign. 1995 Bates No 2501021084/1154. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/led67d00.

- 73.Philip Morris Europe SA. Pan-European advocacy campaign. 1995. Philip Morris. Bates No 2046537828/7884. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kmn57d00.

- 74.Proctor RN. The Nazi war on cancer. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 75.FORCES. Philip Morris., editor. FORCES fight ordinances and restrictions to control and eliminate smoking. 1995 Oct; Bates No 2073643685/3686. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/shc37d00.

- 76.Givel M. Consent and counter-mobilization: The case of the national smokers alliance. J Health Commun. 2007;12:339–57. doi: 10.1080/10810730701326002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights. [accessed 2 November 2007];Frontgroups and allies: FORCES. Available from http://www.no-smoke.org/getthefacts.php?id=73.

- 78.Traynor MP, Begay ME, Glantz SA. New tobacco industry strategy to prevent local tobacco control. JAMA. 1993;270:479–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.FORCES. [accessed 2 Nov 2007];The forces archive. 2007 Available from http://www.forces.org/Archive/

- 80.O’Rourke PJ. Speech at Cora global conference. British American Tobacco; 6 May, 1999. Bates No 321452552-321452559. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/nqa54a99. [Google Scholar]

- 81.High H. [accessed 29 August 2007];Common sense goes up in smoke. 2000 29 March; Available from http://www.data-yard.net/who/hh.htm.

- 82.Ayn Rand I, Harriman Reynolds RJ, editor. Press release. Op-ed general release. The tobacco gestapo. The tobacco settlement is a massive assault on individual rights. 2000 13 Nov; Bates No 522927624/7626. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bac60d00.

- 83.Williams W. Philip Morris., editor. Tribune-Review. Lifestyle Nazis’ work continues. 2000 1 Mar; Bates No 2083550800/0950. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yty35c00.

- 84.Cockburn A. Philip Morris., editor. Viewpoint: the great American smoke screen. 1988 16 Jun; Bates No 2025425690/5692. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/reo04e00.

- 85.Philip Morris. Health fascists hide behind smokescreen. 1993 22 Sep; Bates No 2025837122. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zwq95e00.

- 86.Zion S. Passive smoking doesn’t cause cancer. Yes! British American Tobacco; 26 Mar, 1998. Bates No 321616820. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/vqz24a99. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Coutinho JP. [accessed 20 Nov 2007];Crimes e castigos. 2005 Available from http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/folha/pensata/ult2707u5.shtml.

- 88.La dictadura de los no fumadores. Revista Veintitres. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Freeman UM. [accessed 3 March 2008];Die antiraucher kampagne der nazis heute—nichtrauchen ist eine nazi-idiologie. 2007 April 14; Available from http://alles-schallundrauch.blogspot.com/2007/04/die-anti-raucher-kampagne-wurde-von-den.html.

- 90.Boot M, FMS Philip Morris., editor. Rule of law: even tobacco companies have the right to advertise. 1996 11 Sep; Bates No 2065376430/6432. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/riw77d00.

- 91.Dimanno R. [accessed 2 November 2007];Toronto star columnist invites lynching—rage, rage against the dying of the lighters. [Blog] 2004 Available from http://thelondonfog.blogspot.com/2004/06/toronto-star-columnist-invites.html.

- 92.Little R. [accessed 2 November 2007];Resist the Tobacco Taliban. [e-newspaper] 2006 Available from http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/article678916.ece.

- 93.Clark S. [accessed 2 November 2007];Northern Ireland falls to the tobacco taliban. 2007 April 30; Available from http://takingliberties.squarespace.com/display/ShowJournal?moduleId=1148527&filterBegin=2007-04-01T00:00:00Z&filterEnd=2007-04-30T23:59:59Z.

- 94.Eddie D. [accessed 2 November 2007];Smoking ban forces pub out of business. 2007 Available from http://edinburghnews.scotsman.com/index.cfm?id=351932007.

- 95.Hart B. [accessed 2 November 2007];Smokers are easiest target in this tolerant age. 2006 26 June; Available from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4155/is_20060326/ai_n16173476.

- 96.Sebrie EM, Barnoya J, Perez-Stable E, et al. Tobacco industry dominating national tobacco control policy making in Argentina 1966–2005. San Francisco: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hitt D. [accessed 4 Dec 2007];Nicotine Nazis. 2002 Available from http://www.davehitt.com/nov02/nicotine.html.