Summary

Physical characteristics of water (O2 solubility and capacitance) dictate that cardiovascular and ventilatory performance be controlled primarily by the need for oxygen uptake rather than carbon dioxide excretion, making O2 receptors more important in fish than in terrestrial vertebrates. An understanding of the anatomy and physiology of mechanoreception and O2 chemoreception in fishes is important, because water breathing is the primitive template upon which the forces of evolution have modified into the various cardioventilatory modalities we see in extant terrestrial species. Key to these changes are the O2-sensitive chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors, their mechanisms and central pathways.

Keywords: review, fish, gill, nerve, oxygen, chemoreceptor, mechanoreceptor

Introduction

Fish as a Model to Study the Evolution of Cardioventilatory Control in Vertebrates

From bacteria to mammals, representative species from virtually all taxa have the ability to sense and respond to changes in environmental oxygen availability and/or metabolic demand. However, disproportionately more is known about O2 chemoreception in mammals than any other species despite the fact that they make up only about 10% of known vertebrate species, whereas fish make up over 50% (Groombridge, 1992). Important insights into the physiological mechanisms stimulated by hypoxia may be learned from experiments on different vertebrates. This is an excellent application of the Krogh principle (Krebs, 1975) which basic tenant states that for any biological question there is an experimental organism that is best suited biologically/physiologically to address that question. For example, studies on lower vertebrates have provided valuable insights into the mechanisms of ventilatory rhythmogenesis (Remmers et al., 2001) and cardiovascular physiology (Burggren and Warburton, 1994; Ostadal et al., 1999). Thus, since fish routinely experience natural extremes in O2 availability that no mammal would experience nor could survive, they provide a critical experimental model and represent an important stage in the evolution of O2 chemoreception in vertebrates. The general consensus is that the carotid body and sinus of mammals was derived from the gill arches of their aquatic ancestors (Milsom and Burleson, 2007).

We know that the evolutionary history of vertebrates begins in water (Griffith, 1987). The significance of this is that O2 chemoreception in vertebrates evolved in an environment where hypoxia was routine and probably a very strong selection factor. Thus, it is likely O2 chemoreceptive mechanisms that, for example, allow cardioventilatory acclimatization to hypoxia, are an integral part of the O2 transduction pathway, one that is conserved in terrestrial vertebrates despite the abundance and stability of O2 in air.

Aquatic hypoxia continues to be a problem today. Expanding human activity in watersheds and along the coasts leads to eutrophication which creates hypoxic conditions and exacerbates naturally occurring hypoxia world-wide (Diaz, 2001). Hypoxia is routine in aquaculture facilities and is often the result of over-stocking or over-feeding. Pollution, parasitism, injuries and disease can cause hypoxemia in the absence of aquatic hypoxia. Most attention has been focused on the role hypoxia has on mass mortality and declining fish production (Wu, 2002), however, it is also known that long-term, sublethal hypoxia affects physiological control mechanisms in vertebrates. While many studies have examined the role of O2 receptors mediating the acute effects of hypoxia in fishes, few have studied how long-term hypoxia affects cardioventilatory control.

O2 Chemoreflexes

O2-sensitive chemoreceptors mediate changes in cardioventilatory performance and perfusion patterns in response to hypoxia in order to maintain aerobic metabolism. The cardioventilatory reflex responses of fishes to hypoxia and hypoxemia vary with species, age, level of hypoxia and the ability to breathe air. In water-breathing teleost fishes the most common ventilatory response is an increase in ventilation. The pattern of the ventilatory increase varies. Most show increases in both frequency and amplitude but some, depending on age and species, only show increases in one or the other variable. Because breathing water is metabolically expensive, some fish decrease ventilation to conserve energy and utilize anaerobic metabolism, especially during periods of prolonged hypoxia. Some fish respond to hypoxia with aquatic surface respiration (Kramer and Mehegan, 1981; Sundin et al., 2000). These fish go to the surface of the water and breathe the thin layer of water in contact with the atmosphere where O2 is most available. Air breathing fish often suspend gill ventilation when they begin breathing air during hypoxia because under hypoxic conditions O2 can be lost from the blood to the water through the gills (Graham, 1997). Also in air breathing fish, air breaths may not be for gas exchange but to maintain buoyancy (Hedrick and Jones, 1999).

Cardiovascular reflex responses to hypoxia mediated by O2 receptors are bradycardia and increased blood pressure. Cardiac output is maintained, despite bradycardia, by increased stroke volume (Fritsche and Nilsson, 1989). Bradycardia is believed to increase the residence time of blood in the gills to better oxygenate blood in the face of a reduced transbranchial O2 gradient. The increase in blood pressure is due to increased systemic vascular resistance (Fritsche and Nilsson, 1989; Sundin et al., 1999). However, like ventilation there is variability in the cardiovascular response between different species.

Location and innervation of O2 chemoreceptors

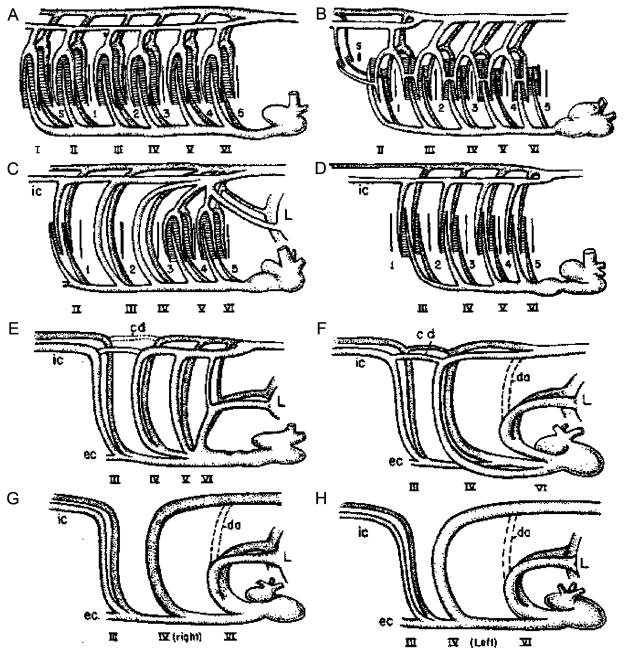

The precise anatomical location and identification of O2-sensitive chemoreceptors in fish is not completely certain but evolutionary inferences as well as anatomical and physiological evidence strongly suggest the gills as the major locus. The carotid and aortic arches, where O2 chemoreceptors are located in mammals, are believed to be derived from the gill arches of an aquatic vertebrate ancestor (Figure 1, Romer, 1962). A number of studies on a wide variety of fish have now indirectly localized piscine O2 chemoreceptors to the gills (reviewed by Perry and Gilmour, 2002 and Sundin and Nilsson, 2002), but there is also evidence for extrabranchial O2 receptors (Milsom et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

Evolution of the aortic arches in vertebrates from a hypothetical ancestor with six gill archers (A) through elasmobranchs (B), lungfish (C), teleosts (D), amphibians (E), reptiles (F), birds (G) and mammals (H). Corresponding with increasing degrees of terrestriality and air-breathing there is an internalization and reduction of the number of arches. (From Romer, 1962).

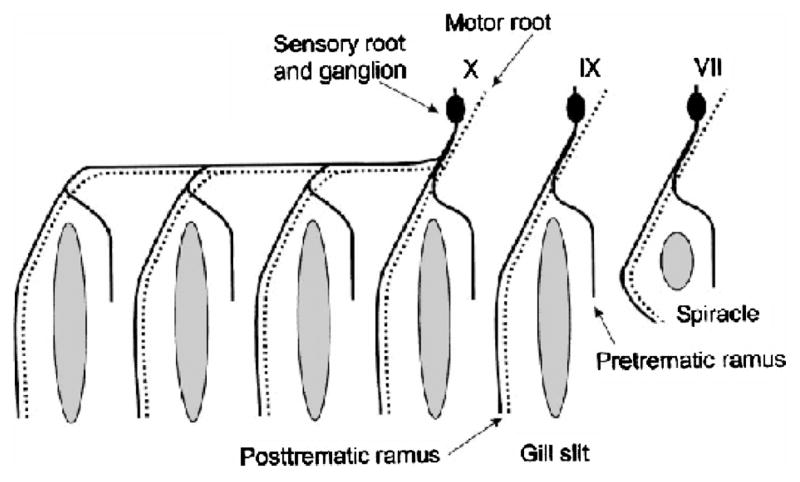

There is considerable variation in the number and anatomy of gills in fishes (Hughes, 1984). The anatomy of the gills of agnathans (not true fish), elasmobranchs and teleosts are very different (see Wilson and Laurent, 2002 for a recent review). Some fish have pseudobranchs which may be exposed on the inner surface of the operculum and appear as a reduced gill as in salmonids or it may be covered by epithelium and embedded in the tissues of the upper buccal cavity and have a glandular appearance as in the bowfin, Amia calva. Other groups of fishes, for example the Anguilliformes (eels) and Siluroidei (catfish), have no pseudobranchs (Lagler et al., 1977). Regardless, the pattern of branchial innervation is consistent amongst all fishes and is illustrated in Figure 2. Despite internalization and loss of gill arches during the evolution of vertebrates (Figure 1), this fundamental pattern of innervation persists, even in mammals. Branches of cranial nerves V, VII, IX and X innervate the gills and pseudobranch, when present. Each arch is innervated by pre- and post-trematic branches (Figure 2). The pseudobranch, when present is innervated by a post-trematic branch of V and a pre-trematic branch of IX. The first gill arch is innervated by a post-trematic branch of IX and a pre-trematic branch of X. All subsequent arches are innervated by pre- and post-trematic branches of X. The pre-trematic branch is sensory and the post-trematic branch is both motor and sensory (Nilsson, 1984).

Figure 2.

Diagram of innervation of the gills showing pre- and post-trematic branches and sensory (solid) and motor (dotted) pathways. (Reprinted with permission from Sundin and Nilsson, 2002).

Most studies to localize O2 chemoreceptors in fishes have sectioned the nerves to putative chemoreceptive regions (i.e. cranial nerves to the gill arches) then exposed the fish to hypoxia or cyanide to determine if the reflex responses (bradycardia, hypertension and increased ventilation) have been abolished. While this has been a useful way to identify chemoreceptor location, because of the complex innervation of the gills and their critical role in gas exchange and other physiological functions, there are some potential problems associated with this procedure. One must remember that these nerves are a heterogeneous mix of axons. There are both afferent and efferent axons in these nerves and within each of these classes of axons there are multiple sensory receptors (chemoreceptors, mechanoreceptors, baroreceptors) and effectors (filament muscles and vascular shunts) that have the potential to influence the cardioventilatory responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia directly and indirectly. For example, the release of circulating catecholamines from chromaffin cells in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) is mediated by internally oriented O2 receptors in the gills (Reid and Perry, 2003). Although most nerve section studies do not measure blood gases, it has been shown that denervation of the gills can affect blood gas values (Saunders and Sutterlin, 1971; McKenzie et al., 1991; Burleson and Smatresk, 1990). Sectioning all branchial innervation, while having little effect on resting cardioventilatory values (heart rate and ventilation), reduces dorsal aorta blood PO2 by 90% and doubles the PCO2 in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) (Burleson and Smatresk, 1990) probably as a result of removing efferent control of the gill filaments and vasculature (Nilsson and Sundin, 1998) and/or by the direct effect of hypoxia on the gill vasculature (Smith et al., 2001).

Scientists have been sectioning branchial nerves in fish for almost 100 years (Deganello, 1908; Reid and Perry, 2003) in an effort to learn more about cardioventilatory control in fish. Most evidence indicates that in fish, O2-sensitive chemoreceptors can be found on all gill arches and are innervated primarily by cranial nerves IX and X (see Perry and Gilmour, 2002 and Sundin and Nilsson, 2002 for recent reviews) and, in some species, diffusely distributed in the oro-branchial cavity (Butler et al., 1977; Milsom et al., 2002). It is beginning to appear that the distribution of O2 receptors, like the reflex responses to hypoxia, are highly variable from species to species and perhaps from one physiological process to another. In some species, O2-sensitive chemoreceptors may be present in the spiracle and pseudobranch and are innervated by cranial nerves VII and IX (Burleson et al., 1992; Milsom, 1998), as well as within the walls of the orobranchial cavity innervated by cranial nerves V and VII (Butler et al., 1977; Milsom et al., 2002). The distribution of O2 receptors controlling hypoxic bradycardia is restricted to the first gill arch in many species such as rainbow trout (Smith and Jones, 1978), Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua, Fritsche and Nilsson, 1989) and traira (Hoplias malabaricus, Sundin et al., 1999). These receptors are on the first three pairs of gill arches in channel catfish (Burleson and Smatresk, 1990) and on all of the gill arches in tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum, Sundin et al., 2000). In the elasmobranch, dogfish shark (Scyliorhinus canicula) the O2 receptors mediating hypoxic bradycardia have a diffuse distribution within the orobranchial cavity (Butler et al., 1977; Taylor et al., 1977). The receptors associated with the hypoxic ventilatory response are confined to the gill arches in channel catfish (Burleson and Smatresk, 1990) while in many other fishes, total gill denervation fails to eliminate the response (Saunders and Sutterlin, 1971; Hughes and Shelton, 1962; Sundin et al., 1999; Milsom et al., 2002). Sectioning all branchial nerves as well as cranial nerves V and VII in tambaqui abolished the ventilatory response to hypoxia and cyanide indicating that in this species there are O2 receptors in the buccal/pharyngeal region as well as the gills. That O2 receptors are found in the buccal/pharyngeal region in places other than the gills should not be completely surprising given that the jaws were derived from gill arches (Mallatt, 1996).

The responses to hypoxia of air-breathing fishes usually differ from water-breathers. Air-breathing in fishes has evolved many times and many different parts of the buccal and pharyngeal cavities as well as the alimentary canal have been modified to extract O2 from air. The most derived forms make use of either air breathing organs or true lungs (Graham, 1997). O2-sensitive chemoreceptors in these fishes now regulate not only changes in heart rate and gill ventilation but also ventilation of the air breathing organs. Much less is known about the sites and innervation of the O2-sensitive chemoreceptors that stimulate gill ventilation and air breathing in fish that use bimodal respiration. In the Actinopterygian fishes, the gar and bowfin, they are found diffusely distributed throughout the gills and pseudobranch innervated by cranial nerves VII, IX and X (McKenzie et al., 1991; Smatresk et al., 1986). In the Dipnoan lungfishes, they are also distributed throughout the anterior hemibranch and all gill arches innervated by cranial nerves VII, IX and X. The data suggest that, in lungfishes, ventilatory reflexes arise principally, but not exclusively from receptors in the hemibranch and the anterior two (filament-free) arches (Lahiri et al., 1970).

Identification of putative O2 chemoreceptor cells

Although it has become clear that all cells respond in various ways to hypoxia, only two types, glomus (Type 1) associated with the vasculature (carotid and aortic bodies) and neuroepithelial cells associated with respiratory epithelia are generally accepted as specific O2-sensitive chemoreceptors (Cutz and Jackson, 1999). Glomus and neuroepithelial cells have the same embryological origin, the neural crest, and are characterized by large spherical nuclei, numerous mitochondria, well developed Golgi apparatus and dense core vesicles containing various neurochemicals. Both cell types have cytoplasmic processes that make contact with nerves, capillaries and other glomus cells (Verna, 1997; Adriaensen et al., 2003). Some glomus and neuroepithelial cells do not appear to be innervated yet others are innervated by both afferent and efferent nerves (Adriaensen et al., 2003). The presence of gap junctions indicates that there is direct communication between glomus cells in a cluster (Eyzaguirre, 2000) suggesting that they may function together as a unit. Sustentacular cells (Type II cells) are closely associated with glomus and neuroepithelial cells and although they do not appear to play a direct role in O2 chemoreception they may be necessary for normal chemoreceptor function (Verna, 1997).

Lacking carotid bodies, fish do not have glomus cells. However, they do have neuroepithelial cells which are histologically very similar to glomus cells and have been found in the lungs and respiratory passages of all vertebrates examined (Van Lommel et al., 1999; Adriaensen et al., 2003; Zaccone et al., 1997). Although the hypoxic reflexes that may be mediated by these receptors are not well defined, they are considered to be O2-sensitive chemoreceptors based on their electophysiological responses to hypoxia (Youngson et al., 1993). It has been suggested that pulmonary neuroepithelial cells may be important for O2 chemoreception in very young animals born with immature lungs (Van Lommel et al., 1999) because young animals typically have blunted carotid body O2 reflexes (Donnelly, 2000). Neuroepithelial cells have been described in the gills and air-breathing organs of over 10 different species of fishes (Laurent, 1984; Zaccone, et al., 1992, 1995, 1997; Jonz and Nurse, 2003).

Neuroepithelial cells in the gills and airways of non-mammalian vertebrates may occur singly or in innervated clusters called neuroepithelial bodies (see Adriaensen et al., 2003; Zaccone, et al., 1994; Van Lommel et al., 1999 for reviews). In many cases neuroepithelial bodies are found in close association with capillaries (Adriaensen et al., 2003; Goniakowska-Witalinska, 1997). Neuroepithelial cells have also been classified as either “open” or “closed” type cells and have been described in the gills and air breathing organs of fish and in amphibian lungs (Zaccone et al., 1992; Goniakowska-Witalinska, 1997). Open cells are found in the outer epithelial layers and make contact with the mucosal surface of the gas exchange organs. This location puts them in a good position to monitor the ventilatory flow, be it water or air. Open type cells are polarized. The apical membrane is in contact with the respiratory passages and has cilia or microvilli. Dense core vesicles are concentrated in the basal portion of the cell where they come into synaptic contact with nerves (Van Lommel, et al., 1999) suggesting a sensory function. Closed type cells are similar to open type but are located on the basal lamina separated from the ventilatory flow often by several layers of cells.

Branchial neuroepithelial cells are currently the best candidates for O2 chemoreceptor cells that mediate reflex responses to hypoxia in fish. In the gills, these cells are located in the primary epithelium of the gill filaments. They lie on the basal lamina between the inhalant water flowing over the gill and blood flow through the gill in an ideal anatomical location to function as O2 sensors (Dunel-Erb et al., 1982). Branchial neuroepithelial cells share many of the characteristic anatomical features of mammalian O2-sensors (glomus and pulmonary neuroepithelial cells). Like mammalian cells, some branchial neuroepithelial cells are innervated, possess a well developed Golgi complex and numerous mitochondria and dense-cored vesicles (Dunel-Erb et al., 1982; Laurent, 1984; Zaccone et al., 1995). Falck-Hillarp fluorescence (Dunel-Erb et al., 1982) and immunohistochemistry (Zaccone et al., 1995; Jonz and Nurse, 2003) have shown that the major monoamine contained within these cells is serotonin.

Although the morphology and location of branchial neuroepithelial cells are suggestive of an O2-sensitive chemoreceptor, histological and cytochemical data are supported by only a few direct physiological studies. An O2 sensory function is suggested by the fact that hypoxia causes degranulation of the dense-cored vesicles and reduces monoamine content (Laurent, 1984) similar to the degranulation seen in mammalian glomus cells during hypoxia (Fidone and Gonzalez, 1986). Afferent O2-sensitive activity has been recorded from the gills of fish (Milsom and Brill, 1986; Burleson and Milsom, 1993) but it cannot be determined from these studies if the activity was from branchial neuroepithelial cells. Electrophysiological studies on neuroepithelial cells in channel catfish gills and zebra fish demonstrate O2-sensitive outward currents (Mercer et al., 2000; Jonz et al., 2004) similar to those of mammalian glomus (reviewed by Prabhakar and Overholt, 2000 and Lahiri et al., 2001) and pulmonary neuroepithelial cells (Youngson et al., 1993). The dissociated cells from catfish were also immunopositive for serotonin, neuron-specific enolase and tyrosine hydroxylase (Burleson et al., 2006).

Goniakowska-Witalińska (1997) proposed a three-tiered scenario for the evolution of neuroepithelial cells in vertebrates based on studies in extant species. The first type are the most primitive and are solitary non-innervated neuroepithelial cells. These may be closed, deep in tissue or open, in contact with the ventilatory flow. This is the predominant pattern seen in larval Salamandra lungs and the respiratory swim bladders of the Actinopterygian fishes Polypterus (bichir) and bowfin. The next step is innervation of the solitary neuroepithelial cells. Again, these may be the closed type as seen in the amphibian Triturus or open as seen in the Sarcopterygian lungfish Protopterus. The most advanced form of neuroepithelial cells are the innervated clusters or pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies of mammals. These show afferent as well as efferent innervation and gap junctions between cells to form a chemoreceptor “unit”.

Mechanoreceptors

In contrast to O2-sensitive chemoreceptors, the physiology, histology and reflex effects of branchial mechanoreceptors in fishes have received much less attention. Neurophysiological and reflex studies have identified mechanoreceptors sensitive to blood pressure, movements of the filaments, rakers and gill arch in several different species of teleost fish and elasmobranchs (Burleson et al., 1992; Taylor et al., 1999 for reviews). There are few histochemical studies on gill mechanoreceptors but most report simple free nerve endings (Ballintijn and Bamford, 1975). Therefore, their location in the gill determines their sensory modalities and discharge characteristics.

The physiological functions of branchial mechanoreceptors are varied and largely depend upon where they are located in the gill. Experimental evidence suggests that they may mediate ram ventilation, cardioventilatory synchrony, cough/expulsion reflexes and maintenance of the “gill curtain” to minimize ventilatory dead space. Mechanoreceptors in the gill vasculature, baroreceptors, are believed to play a role in the cardiovascular responses to changing blood pressure.

Nerve activity has been recorded from gill filament receptors in carp (Cyprinus carpio), sea raven (Hemipterus americanus), Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) (see Burleson et al., 1992 and Taylor et al., 1999 for reviews). The receptive field for each receptor may include one or several filaments. Both rapidly-adapting (phasic) and slowly-adapting (tonic) filament receptors have been demonstrated. In vivo nerve recordings from channel catfish show activity during normal ventilation and flow sensitivity (Burleson et al., 2001). Unlike pulmonary and respiratory swim bladder mechanoreceptors, stretch receptors, these showed no CO2 sensitivity.

Current hypotheses suggest that these receptors may play a protective role by mediating cough/expulsion reflexes as well as minimizing ventilatory dead space by coordinating filament muscle movements to maintain the gill curtain. Subsequent experiments examining efferent control of gill filament indicate that rhythmic feedback from phasic mechanoreceptors is not involved in the breath-to-breath timing of ventilation (Burleson and Smith, 2001).

Gill rakers have also been shown to be innervated by mechanoreceptors. Rapidly-adapting and slowly-adapting raker mechanoreceptor activity has been recorded from several fish species in vivo and in vitro (Burleson et al., 1992). The mechanoreceptors in the rakers are not active during normal ventilatory movements in carp (de Graaf et al., 1987), therefore, may only play a role in cough/expulsion reflexes and feeding. At present, there have been too few studies on gill raker mechanoreceptors to draw firm conclusions.

Gill arch proprioceptors are located in the flexible cartilage that connects the epibranchial (dorsal) and ceratobranchial (ventral) components of the gill arch. In carp, these receptors are active during normal ventilation showing an increase in discharge during abduction and a decrease during adduction. De Graaf and Ballintijn (1987) suggest that gill arch proprioceptors, of all the gill mechanoreceptors, are the best candidates for controlling breathing patterns and cardioventilatory synchrony.

Arterial mechanoreceptors, baroreceptors, respond to distortion of vessel walls caused by changes in blood pressure. In terrestrial vertebrates, the baroreceptors that mediate a majority of the cardioventilatory reflexes are found in the carotid sinus and aortic arch, anatomical/evolutionary homologs of the gill arches. Histologically, these receptors have been shown to be free nerve endings.

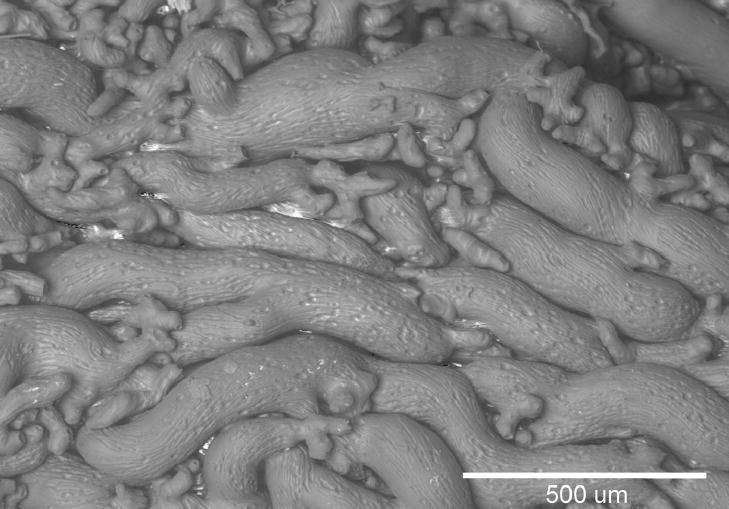

The primary reflex response to an increase in branchial blood pressure in fishes is bradycardia which likely protects the delicate gill vasculature. To date, all of the branchial baroreceptors recorded from have been rapidly adapting (Burleson et al., 1992). The only baroreceptive loci positively identified in fishes have been the gills and pseudobranch (Burleson et al., 1992). Histological studies have shown several potential loci within the gills for baroreceptors. Early studies by Boyd (1936) and DeKock (1963) suggest the junction of the afferent branchial artery and efferent filamental artery. Later studies by Funakoshi et al., (1999) identified nitrergic nerve fibers in the puffer fish (Takifugu niphobles) terminating in free nerve endings on the efferent filament artery. The morphology and histochemistry of these neurons are very similar to mammalian baroreceptors. Carotid labyrinths are found in some catfish and are very similar to the carotid sinus of higher vertebrates (Figure 3). Currently, no physiological function as been ascribed to these structures, however, their location, morphology and innervation suggest a sensory role (Olson et al., 1981).

Figure 3.

Scanning electron micrograph of vascular cast of carotid sinus from channel catfish. The catfish carotid sinus is between the first gill arch and brain and is formed when the first branchial artery anastomoses into a compact mass of capillaries. Its structure and location, similar to mammalian carotid sinus and amphibian carotid labyrinth, suggests a baro- or chemoreceptor function.

Central Projections

The branchial branches of cranial nerves V, VII, IX and X send afferent fibers to sensory nuclei that are located in the medulla dorsal and lateral to the sulcus limitans of His, arranged sequentially and immediately above their respective motor nuclei (Figure 4) (Nieuwenhuys and Pouwels, 1983; Taylor et al., 1999). This area, the general visceral nucleus, is in the vagal lobe of the brain (Kanwal and Caprio, 1987) and is equivalent to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) where carotid and aortic afferents terminate in mammals. It is likely where all sensory information from the gills and orobranchial cavity (O2 and CO2 chemoreception, baroreception, proprioception, taste) is integrated in fishes.

Figure 4.

Diagram of dorsal view of brainstem of a dogfish shark showing cranial nerve roots (V–XI) and locations of the major motor and sensory nuclei. A transverse section of the medulla at T.S. is shown to the left. Relevant labels are motor nuclei of the branchial branches of the vagus (Xm1-4), vagal sensory nucleus (Xs), hypobranchial nucleus (hy), lateral vagal nucleus (XI), sulcus intermedius ventralis (siv) and sulcus limitans of His (slH). (Reprinted with permission from Taylor et al., 1999).

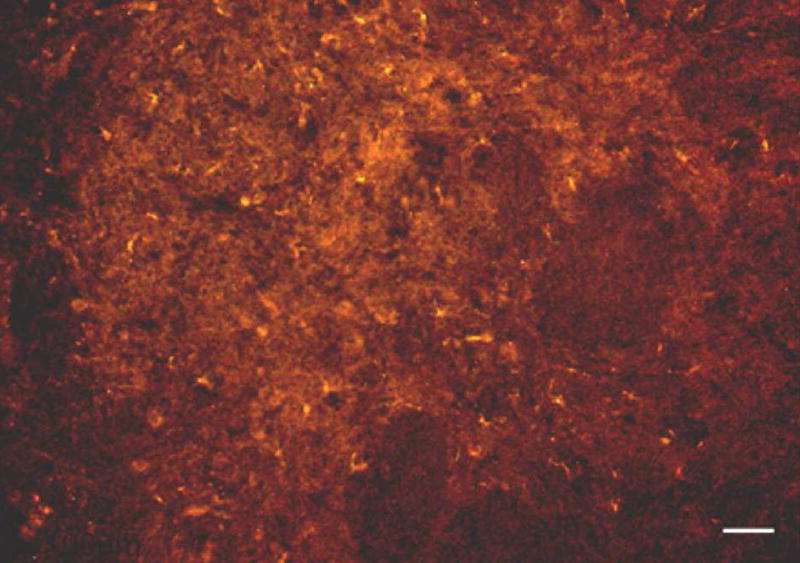

Recent experiments on shorthorn sculpin (Myoxocephalus scorpius) and channel catfish have shown this area to be critical for maintaining cardioventilatory responses to hypoxia (Turesson and Sundin, 2003; Sundin et al., 2003a; Sundin et al., 2003b). Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated glutamate and NMDA receptors in the vagal sensory nucleus (Figure 5). Microinjections of glutamate into the vagal sensory nuclei of sculpin alter cardioventilatory variables much the same way as hypoxia and cyanide (Sundin et al., 2003a). The NMDA antagonist, MK801, mediates increases in blood pressure and ventilatory frequency in response to cyanide but not the bradycardia or increased ventilatory amplitude, suggesting that there are separate pathways for each cardioventilatory variable. Microinjections of kynurenic acid, a NMDA antagonist, in the vagal sensory nuclei abolished ventilatory responses to hypoxia in channel catfish but not normal ventilation. However, when lesions were made in the same area with kainic acid all ventilatory movements stopped. These observations suggest that kainic acid lesions interrupt continuous sensory input that keeps a conditional rhythm generator above threshold and drives resting ventilation (Milsom, 1998).

Figure 5.

Micrograph showing NMDA Receptor 1-like immunoreactivity in the vagal sensory lobe of the channel catfish brain. Scale bar = 100μm. (From Sundin et al., 2003a)

The central distribution and integration of inputs from different populations of chemoreceptors in air-breathing fish must be even more complex, since differences in levels of hypoxia and hypoxemia can produce very different net effects on gill versus air breathing. Thus, in exclusively water breathing fish, hypoxia stimulates gill ventilation, whereas, in facultative air breathing fish it decreases gill ventilation and stimulates air breathing while in obligate air breathing fish it only stimulates air breathing. This picture is compounded by the differences in the distribution of receptors sensitive to internal versus external changes in O2. Interestingly, a similar transition is seen ontogenetically in the amphibian tadpole (Jia and Burggren, 1997a,b; West and Burggren, 1982, 1983). Smatresk et al. (1986) have suggested that in gar, at least, the information from internal receptors is used to set the level of hypoxic drive while that from external receptors sets the balance between air breathing and gill ventilation.

While much work has centered on describing the functional subdivisions of the NTS and the topographical distribution of inputs relative to cardiovascular control in air breathing vertebrates (primarily mammals) (Andresen and Kunze, 1994; Dampney, 1994; Marshall, 1994), there are far fewer studies of respiratory related inputs. Discussion of these data are beyond the scope of this review but evidence suggests that significant integration does occur in the NTS (England et al., 1995; Tian and Duffin, 1998) involving several transmitter/receptor systems (Bianchi et al., 1995; McCrimmon et al., 1995) which experience different degrees of neuromodulation over different time domains (McCrimmon et al., 1995; Powell et al., 1998).

Too little is yet known to make any generalized statements about central projections and integration of afferent information arising from the O2-sensitive chemoreceptors. It is clear, however, that in lower vertebrates, where environmental hypoxia is common and where species possess multiple sites for O2 chemoreception, possess multiple sites of gas exchange (gills and lungs), and possess multiple strategies for dealing with hypoxia (changes in cardiac shunt versus ventilation), to make appropriate changes in ventilation and perfusion of the gas exchange surfaces that most effectively increase oxygen transport under different conditions requires the complex central integration of distinct afferent inputs. This would tend to suggest that the NTS in fishes may play an even more important role in cardiorespiratory integration than it does in mammals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant HL076205-01, Texas Parks and Wildlife and The Department of Biological Sciences, University of North Texas.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adriaensen D, Brouns I, Van Genechten J, Timmermans J-P. Functional morphology of pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies: extremely complex airway receptors. Anat Rec. 2003;270A:25–40. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen MC, Kunze DL. Nucleus tractus solitarius – gateway to circulatory control. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:93–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballintijn CM, Bamford OS. Proprioceptive motor control in fish respiration. J Exp Biol. 1975;62:99–114. doi: 10.1242/jeb.62.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi AL, Denavit-Saube M, Champagnat J. Central control of breathing in mammals: neuronal circuitry, membrane properties and neurotransmitters. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:1–45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JD. Nerve supply to the branchial arch arteries of vertebrates. J Anat Lond. 1936;71:157–158. [Google Scholar]

- Burggren WW, Warburton SJ. Patterns of form and function in developing hearts: contributions from non-mammalian vertebrates. Cardioscience. 1994;5:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson ML, Smatresk NJ. Effects of sectioning cranial nerves IX and X on cardiovascular and ventilatory reflex responses to hypoxia and NaCN in channel catfish. J Exp Biol. 1990;154:407–420. [Google Scholar]

- Burleson ML, Smatresk NJ, Milsom WK. Afferent inputs associated with cardio-ventilatory control in fish. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ, Farrel AF, editors. Fish Physiology, Vol. XII Part B: The Cardiovascular System. Academic Press; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burleson ML, Milsom WK. Sensory receptors in the first gill arch of rainbow trout. Respir Physiol. 1993;93:97–110. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(93)90071-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson ML, Smith RL. Central nervous control of gill filament muscles in channel catfish. Respir Physiol. 2001;126:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson ML, Soard JD, Elikan LP. Branchial mechanoreceptor activity during spontaneous ventilation in channel catfish. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A. 2001;128:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(00)00283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson ML, Mercer SE, Wilk-Blaszczak MA. Isolation and characterization of putative O2 chemoreceptor cells from the gills of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) Brain Res. 2006;1092:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler PJ, Taylor EW, Short S. The effect of sectioning cranial nerves V, VII, IX and X on the cardiac response of the dogfish, Scyliorhinus canicula, to environmental hypoxia. J Exp Biol. 1977;69:233–245. doi: 10.1242/jeb.69.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutz E, Jackson A. Neuroepithelial bodies as airway oxygen sensors. Respir Physiol. 1999;115:201–214. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RA. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:323–64. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deganello U. Die peripherischen, nervösen apparate des atmungsrythmus bei knochenfischen. Pflugers Arch Ges Physiol. 1908;123:40–94. [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf PJF, Ballintijn CM, Maes FW. Mechanoreceptor activity in the gills of the carp. I. Gill filament and gill raker mechanoreceptors. Respir Physiol. 1987;69:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(87)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKock LL. A histological study of the head region of two salmonids with special reference to pressor- and chemo-receptors. Acta Anat. 1963;55:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RJ. Overview of hypoxia around the world. J Environ Qual. 2001;30:275–281. doi: 10.2134/jeq2001.302275x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly DF. Developmental aspects of oxygen sensing by the carotid body. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(6):2296–2301. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunel-Erb S, Bailly Y, Laurent P. Neuroepithelial cells in fish gill primary lamellae. J Appl Physiol. 1982;53:1342–1353. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.6.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England SJ, Melton JE, Douse MA, Duffin J. Activity of respiratory neurons during hypoxia in the chemodenervated cat. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:856–61. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.3.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyzaguirre C. Electrical coupling between glomus cells and nerve terminals. In: Lahiri S, Prabhakar NR, Foster RE, editors. Oxygen Sensing: Molecule to Man. Plenum; London: 2000. pp. 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Fidone S, Gonzalez C. Initiation and control of chemoreceptor activity in the carotid body. In: Cherniack NS, Widdicombe JG, editors. The Respiratory System, Handbook of Physiology. II. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD: 1986. pp. 247–312. Sect. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche R, Nilsson S. Cardiovascular responses to hypoxia in the Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua. Exp Biol. 1989;48:153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi K, Kadota T, Atobe Y, Nakano M, Goris RC, Kishida R. Nitric oxide synthase in the glossopharyngeal and vagal afferent pathway of a teleost, Takifugu niphobles: The branchial vascular innervations. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;298:45–54. doi: 10.1007/s004419900078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goniakowska-Witalińska L. Neuroepithelial bodies and solitary neuroendocrine cells in the lungs of amphibia. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;37:13–30. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970401)37:1<13::AID-JEMT3>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goniakowska-Witalińska L, Zaccone G, Fasulo S, Mauceri A, Licata A, Youson J. Neuroendocrine cells in the gills of the bowfin Amia calva. An ultrastructural and immunocytochemical study. Folia Histo Cyto. 1995;33:171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JB. Air-breathing Fishes. Academic Press; New York: 1997. p. 299. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith RW. Freshwater or marine origin of the vertebrates? Comp Biochem Physiol. 1987;87A:523–531. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(87)90355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groombridge. Global biodiversity: status of the Earth’s living resources. Chapman and Hall; London: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick MS, Jones DR. Control of gill ventilation and air breathing in the bowfin Amia calva. J Exp Biol. 1999;202:87–94. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GM. General anatomy of the gills. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ, editors. Fish Physiology, Vol. X Part A: Gills: Anatomy, Gas Transfer and Acid-Base Regulation. Academic Press; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GM, Shelton G. Respiratory mechanisms and their nervous control in fish. Adv Comp Physiol Biochem. 1962;1:275–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X, Burggren W. Developmental changes in chemoreceptive control of gill ventilation in larval bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana). I. Reflex ventilatory responses to ambient hyperoxia, hypoxia and NaCN. J Exp Biol. 1997a;200:2229–2236. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.16.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X, Burggren W. Developmental changes in chemoreceptive control of gill ventilation in larval bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana). II. Sites of O2-sensitive chemoreceptors. J Exp Biol. 1997b;200:2237–2248. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.16.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonz MG, Nurse CA. Neuroepithelial cells and associated innervation of the zebrafish gill: a confocal immunofluorescence study. J Comp Neurol. 2003;461:1–17. doi: 10.1002/cne.10680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonz MG, I, Fearon M, Nurse CA. Neuroepithelial oxygen chemoreceptors in the zebrafish gill. J Physiol. 2004;560.3:737–752. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal JS, Caprio J. Central projections of the glossopharyngeal and vagal nerves in the channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus: clues to differential processing of visceral inputs. J Comp Neurol. 1987;264:216–230. doi: 10.1002/cne.902640207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer DL, Mehegan JP. Aquatic surface respiration, an adaptive response to hypoxia in the guppy, Poecilia reticulata (Pisces, Poeciliidae) Env Biol Fish. 1981;6:299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs HA. The August Krogh Principle: “for many problems there is an animal on which it can be most conveniently studied”. J Exp Zool. 1975;194:221–226. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401940115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagler KF, Bardach JE, Miller RR, MayPassino DR. Ichthyology. 2. Wiley; New York: 1977. p. 506. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri SE, Szidon JP, Fishman AP. Potential respiratory and circulatory adjustments to hypoxia in the African lungfish. Annu Rev Physiol. 1970;29:1141–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri S, Rozanov C, Roy A, Storey B, Buerk DG. Regulation of oxygen sensing in peripheral arterial chemoreceptors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:755–774. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent P. Gill internal morphology. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ, editors. Fish Physiology, Vol. X. Gills, Part A Anatomy, Gas Transfer, and Acid-Base Regulation. Academic Press; Orlando: 1984. pp. 73–183. [Google Scholar]

- Mallatt J. Ventilation and the origin of jawed vertebrates: a new mouth. Zool J Linnean Soc. 1996;117(4):329–404. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. Peripheral chemoreceptors and cardiovascular regulation. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:543–94. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrimmon DR, Dekin MS, Mitchell GS. Glutamate, GABA and serotonin in ventilatory control. In: Dempsey JA, Pack AI, editors. Regulation of Breathing. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1995. pp. 151–218. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie DJ, Burleson ML, Randall DJ. The effects of branchial denervation and pseudobranch ablation on cardio-ventilatory control in an air-breathing fish. J Exp Biol. 1991;161:347–365. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer SE, Wilk-Blaszczak MA, Burleson ML. A comparative model for the investigation of the electrophysiological basis of oxygen sensing. FASEB J. 2000:407.2. [Google Scholar]

- Milsom WK, Brill RW. Oxygen sensitive afferent information arising from the first gill arch of yellowfin tuna. Respir Physiol. 1986;66:193–203. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(86)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milsom WK. Cardiorespiratory stimuli: receptor cell versus whole animal. Am Zool. 1997;37:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Milsom WK. Phylogeny of respiratory chemoreceptor function in vertebrates. Zoology (Jena) 1998;101:316–332. [Google Scholar]

- Milsom WK, Reid SG, Rantin FT, Sundin L. Extrabranchial chemoreceptors involved in respiratory reflexes in the neotropical fish: Colossoma macropomum (the tambaqui) J Exp Biol. 2002;205:1765–1774. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.12.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milsom WK, Burleson ML. Peripheral arterial chemoreceptors and the evolution of the carotid body. Resp Phys Neurobio. 2007;157:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R, Powels E. The brainstem of actinopterygian fishes. In: Northcutt RG, Davies RE, editors. Fish Neurobiology, 1. Brain Stem and Sense Organs. University of Michigan Press; Ann Arbor: 1983. pp. 25–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S. Innervation and pharmacology of the gills. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ, editors. Fish Physiology, vol. 10, part A, chapt. 3. Academic Press; Orlando: 1984. pp. 185–227. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S, Sundin L. Gill blood flow. Comp Biochem Physiol A. 1998;119:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(97)00397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Flint KB, Budde RB. Vascular corrosion replicas of chemo-baroreceptors in fish: The carotid labyrinth in Ictaluradae and Clariidae. Cell Tissue Res. 1981;219:535–541. doi: 10.1007/BF00209992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostadal B, Ostadalova I, Dhalla NW. Development of cardiac sensitivity to oxygen deficiency: comparative and ontogenetic aspects. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(3):635–59. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SF, Gilmour KM. Sensing and transfer of respiratory gases at the fish gill. J Exp Zool. 2002;293:249–263. doi: 10.1002/jez.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell FL, Milsom WK, Mitchell GS. Time domains of the hypoxic ventilatory response. Respir Physiol. 1998;112:123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(98)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR, Overholt JL. Cellular mechanisms of oxygen sensing at the carotid body: heme proteins and ion channels. Respir Physiol. 2000;122:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SG, Perry SF. Peripheral O2 receptors mediate humoral catecholamine secretion from fish chromaffin cells. Am J Physiol Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R990–R999. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00412.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmers JE, Torgerson C, Harris M, Perry SF, Vasilakos K, Wilson RJ. Evolution of central respiratory chemoreception: a new twist on an old story. Respir Physiol. 2001;129:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer AS. The vertebrate body. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders RL, Sutterlin AM. Cardiac and respiratory responses to hypoxia in the sea raven, Hemipterus americanus, an investigation of possible control mechanisms. J Fish Res Bd Can. 1971;28:491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Smatresk NJ, Burleson ML, Azizi SQ. Chemoreflexive responses to hypoxia and NaCN in longnose gar: evidence for two chemoreceptor loci. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:R116–R125. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.1.R116. Regulatory Integrative Comp. Physiol. 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FM, Jones DR. Localization of receptors causing hypoxic bradycardia in trout (Salmo gairdneri) Can J Zool. 1978;56:1260–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MP, Russell MJ, Wincko JT, Olson KR. Effects of hypoxia on isolated vessels and perfused gills of rainbow trout. Comp Biochem Physiol A. 2001;130:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin L, Nilsson S. Branchial innervation. J Exp Zool. 2002;293:232–248. doi: 10.1002/jez.10130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin L, Reid SG, Kalinin AL, Rantin FT, Milsom WK. Cardiovascular and respiratory reflexes: the tropical fish, traira (Hoplias malabaricus) O2 chemoresponses. Respir Physiol. 1999;116:181–199. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin L, Reid SG, Rantin FT, Milsom WK. Branchial receptors and cardiorespiratory reflexes in a neotropical fish, the tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) J Exp Biol. 2000;203:1225–1239. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.7.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin L, Turesson J, Burleson M. Identification of central mechanisms vital for breathing in channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003a;138:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin L, Turesson J, Taylor EW. Evidence for glutamatergic mechanisms in the vagal sensory pathway initiating cardiorespiratory reflexes in the shorthorn sculpin Myoxocephalus scorpius. J Exp Biol. 2003b;206:867–876. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EW, Short S, Butler PJ. The role of the cardiac vagus in the response of the dogfish Scyliorhinus canicula to hypoxia. J Exp Biol. 1977;70:57–75. doi: 10.1242/jeb.69.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EW, Jordan D, Coote JH. Central control of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and their interactions in vertebrates. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:855–916. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian GF, Duffin J. The role of dorsal respiratory group neurons studied with cross- correlation in the decerebrate rat. Exp Brain Res. 1998;121:29–34. doi: 10.1007/s002210050433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turesson J, Sundin L. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors mediate chemoreflexes in the shorthorn sculpin Myoxocephalus scorpius. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:1251–1259. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lommel A, Bollé T, Fannes W, Lauweryns JM. The pulmonary neuroendocrine system: the past decade. Arch Histol Cytol. 1999;62:1–16. doi: 10.1679/aohc.62.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verna A. The mammalian carotid body: morphological data. In: Gonzalez C, editor. The Carotid Body Chemoreceptors. Landes Bioscience; Austin: 1997. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Youngson C, Nurse C, Yeger H, Cutz E. Oxygen sensing in airway chemoreceptors. Nature. 1993;365(6442):153–155. doi: 10.1038/365153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West NH, Burggren WW. Gill and lung ventilatory responses to steady-state aquatic hypoxia and hyperoxia in the bullfrog tadpole (Rana catesbeiana) Respir Physiol. 1982;47:165–176. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(82)90109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West NH, Burggren WW. Reflex interactions between aerial and aquatic gas exchange organs in larval bullfrogs. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:R770–R777. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.244.6.R770. Regulatory Integrative Comp. Physiol. 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Laurent P. Fish gill morphology: inside out. J Exp Zool. 2002;293:192–213. doi: 10.1002/jez.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu RSS. Hypoxia: from molecular responses to ecosystem responses. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2002;45:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(02)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngson C, Nurse C, Yeger H, Cutz E. Oxygen sensing in airway chemoreceptors. Nature. 1993;365:153–155. doi: 10.1038/365153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccone G, Lauweryns JM, Fasulo S, Tagliafierro G, Ainis L, Licata A. Immunocytochemical localization of serotonin and neuropeptides in the neuroendocrine paraneurons of teleost and lungfish gills. ACTA Zool. 1992;73:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Zaccone G, Fasulo S, Ainis L. Distribution patterns of the paraneuronal endocrine cells in the skin, gills and the airways of fishes as determined by immunohistochemical and histological methods. Histochemical Journal. 1994;26:609–629. doi: 10.1007/BF00158286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccone G, Fasulo S, Ainis L. Neuroendocrine epithelial cell system in respiratory organs of air-breathing and teleost fishes. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;157:277–314. [Google Scholar]

- Zaccone G, Fasulo S, Ainis L, Licata A. Paraneurons in the gills and airways of fishes. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;37:4–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970401)37:1<4::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]