Abstract

Background:

Juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas (JPA), a subgroup of low-grade astrocytomas (LGA), are common, heterogeneous and poorly understood subset of brain tumours in children. Chromosomal 7q34 duplication leading to fusion genes formed between KIAA1549 and BRAF and subsequent constitutive activation of BRAF was recently identified in a proportion of LGA, and may be involved in their pathogenesis. Our aim was to investigate additional chromosomal unbalances in LGA and whether incidence of 7q34 duplication is associated with tumour type or location.

Methods and results:

Using Illumina-Human-Hap300-Duo and 610-Quad high-resolution-SNP-based arrays and quantitative PCR on genes of interest, we investigated 84 paediatric LGA. We demonstrate that 7q34 duplication is specific to sporadic JPA (35 of 53 – 66%) and does not occur in other LGA subtypes (0 of 27) or NF1-associated-JPA (0 of 4). We also establish that it is site specific as it occurs in the majority of cerebellar JPA (24 of 30 – 80%) followed by brainstem, hypothalamic/optic pathway JPA (10 of 16 – 62.5%) and is rare in hemispheric JPA (1 of 7 – 14%). The MAP-kinase pathway, assessed through ERK phosphorylation, was active in all tumours regardless of 7q34 duplication. Gain of function studies performed on hTERT-immortalised astrocytes show that overexpression of wild-type BRAF does not increase cell proliferation or baseline MAPK signalling even if it sensitises cells to EGFR stimulation.

Conclusions and interpretation:

Our results suggest that variants of JPA might arise from a unique site-restricted progenitor cell where 7q34 duplication, a hallmark of this tumour-type in association to MAPK-kinase pathway activation, potentially plays a site-specific role in their pathogenesis. Importantly, gain of function abnormalities in components of MAP-Kinase signalling are potentially present in all JPA making this tumour amenable to therapeutic targeting of this pathway.

Keywords: SNP arrays, 7q34, JPA, LGA, paediatric, BRAF

Juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas (JPA) account for 60–80% of paediatric low-grade astrocytomas (LGA), the most common paediatric brain tumour, and thus are the most frequently encountered subtype of brain neoplasm in children under the age of 19 years. They are classified according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) as WHO grade I (Louis et al, 2007), and occur sporadically throughout childhood or arise in up to 15–40% of children affected with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1; Pollack and Mulvihill, 1997). JPA exhibit distinct features, readily distinguishable from their other LGA counterparts, including clinical course and molecular characteristics, and have better prognosis in affected children (Gajjar et al, 1997; Ishii et al, 1998; Cheng et al, 2000; Tada et al, 2003; Broniscer et al, 2007; Fisher et al, 2008).

Even though they share similar histology, there is heterogeneity between sporadic JPA in terms of localisation, radiologic features, histologic atypia and clinical behaviour, all of which argue for the possibility of genetic disparity between potential JPA subgroups. Typically, JPA occur as exophytic cerebellar tumours, however, they can also arise in the brain stem or the optic pathway, where they behave more aggressively than NF1-associated JPA (Grill et al, 2000), or, more rarely, in the cerebral hemispheres. Maximal surgical resection is the mainstay of therapy, and failure to achieve it remains the main therapeutic concern. Although cerebellar JPA are readily amenable to complete surgical resection, in other less anatomically accessible locations, surgery may result in the persistence of residual disease, which can require further therapy for tumour control, and ultimately lead to increased morbidity/mortality. In addition, some of these extracerebellar JPA seem less circumscribed and may exhibit atypical pathologic features, leading to pathologic misdiagnosis, including into higher grade tumours.

Until recently, the few genetic abnormalities documented in JPA mainly identified chromosomal gains of 7q and trisomy of chromosomes 5, 7 or 8 in some tumours (White et al, 1995; Rickert and Paulus, 2004; Wemmert et al, 2006). Recently several consecutive papers described duplication of 7q34 in LGA including JPA (Bar et al, 2008; Deshmukh et al, 2008; Jones et al, 2008; Pfister et al, 2008; Sievert et al, 2008). However, the data reported are conflicting regarding the subgroup of LGA affected by this genetic event, the size of the duplication and its anatomical localisation within the brain. Indeed, Deshmukh et al (2008) identified amplification of 7q34 in 8 of 10 cerebellar JPA at 138151200–139456000, which included HIPK2, a potential gene of interest. The authors further showed using an immunohistochemical approach that overexpression of HIPK2 was more frequent in LGA than in high-grade gliomas, and that it was more common in infratentorial tumours. Their silencing of HIPK2 in U87 (a glioblastoma (GBM) cell line) decreased the cells proliferation rate. Pfister et al (2008) identified duplication of 7q34 within 139186224–140156951 in 30 of 66 (45.5%) paediatric LGA. This region included BRAF, a gene which was not in the genetic interval described in Deshmukh et al (2008). The authors confirmed the absence of previously described BRAF oncogenic mutations in their sample set, and showed that silencing of BRAF in a LGA cell line decreased cell proliferation rates. However, based on lower resolution BAC arrays, they did not precisely map the genetic region missing other genes potentially critical in the pathogenesis of LGA, including HIPK2. In addition, data from this report suggest that LGA other than JPA may harbour 7q34 duplication and that this genetic alteration is more frequent in non-cerebellar tumours.

Recent reports have indicated a central role for the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in the tumorigenesis of pilocytic astrocytomas and showed that duplication at 7q34 leads to a fusion between KIAA1549 and BRAF resulting in constitutive activation of the BRAF kinase (Jones et al, 2008; Sievert et al, 2008). In particular, Jones et al (2008) focused on JPA and describe a tandem duplication at 7q34 producing a transforming BRAF fusion gene in 29 of 44 tumours (66%), and V600E point mutation of BRAF in two further cases. Sievert et al indicated that 7q34 duplication occurs in 17 of 22 JPA but also report it in 3 of 6 diffuse astrocytomas (LGA grade II).

To determine the specificity of 7q34 duplication to a given subgroup of LGA and identify additional genetic aberrations in tumours that do not carry this duplication, we investigated 115 paediatric brain tumour samples including 57 JPA, and 27 diffuse astrocytomas (Tables 1, 2a and b). Our data indicate that 7q34 duplication is exclusive to JPA and a hallmark of specific anatomical localisations of these tumours within the brain. We identify additional genetic abnormalities in JPA that do not harbour 7q34 duplication, which may help shed light on their pathogenesis. Data from gain of function analysis in immortalised astrocytes further confirm that increased expression of wild-type BRAF is unable to cause malignant transformation on its own however may contribute to an increased response to exogenous triggering of membrane receptors. Moreover, we show that the MAPK pathway is active in all JPA regardless of 7q34 duplication and that all of these tumours may be amenable to therapeutic targeting of this pathway.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 53 sporadic juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas (JPA) included in the study.

| Patients | Age (years) | Location | HIPK2 (qPCR) | BRAF (qPCR) | SNP array | Amplification of 7q34 | pERK (IHC) | BRAFV600E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebellar JPA (n=30) | |||||||||

| 1 | 6 | Cerebellar | ND | ND | 7q34 amp | Y | ND | ND | |

| 2 | 6 | Cerebellar | ND | ND | 7q34 amp | Y | ND | ND | |

| 3 | 6 | Cerebellar | ND | ND | 7q34 amp | Y | ND | ND | |

| 4 | 6 | Cerebellar | ND | ND | 7q34 amp | Y | ND | ND | |

| 5 | 6 | Cerebellar | ND | ND | 7q34 amp | Y | ND | ND | |

| 6 | 6 | Cerebellar | ND | ND | 7q34 amp | Y | ND | ND | |

| 7 | 6 | Cerebellar | ND | ND | 7q34 amp | Y | ND | ND | |

| 8 | 6 | Cerebellar | ND | ND | 7q34 amp | Y | ND | ND | |

| 9 | 4 | Cerebellar | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 10 | 4 | Cerebellar | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 11 | 4 | Cerebellar | N | N | N | N | Pos | WT | |

| 12 | 4 | Cerebellar | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 13 | 4 | Cerebellar | N | N | ND | N | Pos | ND | |

| 14 | 4 | Cerebellar | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 15 | 4 | Cerebellar | ND | ND | N | N | Pos | ND | |

| 16 | 4 | Cerebellar | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 17 | 3 | Cerebellar | N | N | N | N | Pos | WT | |

| 18 | 6 | Cerebellar | N | N | N | N | Pos | BRAFV600E | |

| 19 | 11 | Cerebellar | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 20 | 11 | Cerebellar | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 21 | 6 | Cerebellar | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 22 | 11 | Cerebellar | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 23 | 9 | Cerebellar | N | N | ND | N | Pos | WT | |

| 24 | 4 | Cerebellar | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 25 | 8 | Cerebellar | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 26 | 2 | Cerebellar | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 27 | 9 | Cerebellar | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 28 | 16 | Cerebellar | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 29 | 2 | Cerebellar | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 30 | 14 | Cerebellar | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | N=24/30 |

| Brainstem, hypothalamus and optic pathway (OP) JPA (n=16) | |||||||||

| 31 | 18 | Brainstem | N | N | ND | N | Pos | ND | |

| 32 | 6 | Brainstem | N | N | ND | N | Pos | ND | |

| 33 | 3 | Brainstem | N | N | ND | N | Pos | ND | |

| 34 | 1 | Brainstem | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 35 | 9 | Brainstem | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 36 | 4 | Brainstem | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 37 | 6 | Brainstem | A | N | ND | Y-HIPK2 | Pos | WT | |

| 38 | 6 | OP | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | ND | |

| 39 | 12 | OP | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | ND | |

| 40 | 11 | OP | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 41 | 6 | OP | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND | |

| 42 | 6 | OP | ND | ND | 7q34 amp | Y | ND | ND | |

| 43 | 3 | OP | A | A | ND | Y | Pos | WT | |

| 44 | 7 | OP | A | A | 7q34 amp | Y | Pos | ND | |

| 45 | 6 | OP | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND | |

| 46 | 6 | OP | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND | N=10/16 |

| Hemispheric JPA (n=7) | |||||||||

| 47 | 6 | Parietal | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND | |

| 48 | 10 | Parietal | N | N | N | N | Pos | WT | |

| 49 | 13 | Occipital lobe | N | N | N | N | Pos | WT | |

| 50 | 6 | Temporal | A | N | ND | Y-HIPK2 | Pos | WT | |

| 51 | 4 | Occipital | N | N | ND | N | Pos | WT | |

| 52 | 6 | Temporal | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND | |

| 53 | 15 | Ventricular | ND | N | N | N | Pos | ND | N=1/7 |

| N=35/53 | |||||||||

N=negative; A=amplified; ND=not done; WT=wild type; Pos=positive; qPCR=quantitative real-time PCR; pERK=phospho-ERK; IHC=immunohistochemistry.

Table 2a. Characteristics of the other low-grade gliomas included in this study.

| Patients | Age (years) | Location | Pathology | HIP2K (qPCR) | BRAF (qPCR) | SNP array | Amplification of 7q34 | pERK (IHC) | BRAF V600E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optic pathway NF-1-associated JPA (n=4) | |||||||||

| 54 | 7 | Optic pathway | JPA/NF1 | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND |

| 55 | 7 | Optic pathway | JPA/NF1 | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND |

| 56 | 7 | Optic pathway | JPA/NF1 | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND |

| 57 | 7 | Optic pathway | JPA/NF1 | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND |

| Other low grade gliomas (n=33) | |||||||||

| 58 | 6 | Parietal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND |

| 59 | 7 | Posterior fossa | Diffuse astrocytoma | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND |

| 60 | 2 | Posterior fossa | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | Pos | ND |

| 61 | 14 | Temporal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | Pos | ND |

| 62 | 10 | Temporal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | Pos | ND |

| 63 | 0.25 | Temporal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | A | N | ND | Y-HIP2K | Pos | WT |

| 64 | 6 | Posterior fossa | Diffuse astrocytoma | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND |

| 65 | 13 | Posterior fossa | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 66 | 6 | Temporal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 67 | 5 | Fourth ventricule | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 68 | 2 | Parietal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 69 | 14 | Posterior fossa | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 70 | 12 | Posterior fossa | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 71 | 11 | Temporal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 72 | 10 | Temporal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 73 | 7 | Temporal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 74 | 9 | Posterior fossa | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 75 | 12 | Parietal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 76 | 15 | Temporal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 77 | 2 | Posterior fossa | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 78 | 9 | Parietal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 79 | 18 | Temporal lobe | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 80 | 5 | Brainstem | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 81 | 3 | Brainstem | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 82 | 2 | Hippocampus | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 83 | 11 | Hipothalamus | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 84 | 14 | Posterior fossa | Diffuse astrocytoma | N | N | ND | N | ND | ND |

| 85 | 6 | Frontal lobe | Ganglioglioma | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND |

| 86 | 6 | Brainstem | Ganglioglioma | ND | ND | N | N | ND | ND |

| 87 | 3 | Temporal lobe | Ganglioglioma | N | N | N | N | Pos | WT |

| 88 | 16 | Hippocampus | Ganglioglioma | N | A | N | N | Pos | WT |

| 89 | 1 | Hippocampus | Ganglioglioma | N | N | N | N | Pos | M |

| 90 | 18 | Cauda equina | Ependymoma | N | N | N | N | Pos | WT |

JPA=juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma; M=V600E mutation; NF1=neurofibromatosis 1; SNP=single nucleotide polymorphism; qPCR=quantitative real-time PCR; pERK=phospho-ERK; IHC=immunohistochemistry; N=negative; A=amplified; ND=not done; WT=wild type; Pos=positive; M=mutated.

Table 2b. Clinical characteristics of samples from children with high-rade astrocytomas included in this study.

| Number of patients | 25 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 |

| Female | 11 |

| Median age | 12 years (10–18 months) |

| WHO classification | |

| Astrocytomas grade IV | 18 |

| Astrocytoma grade III | 7 |

| Tumor site | |

| Supratentorial | 18 |

| Infratentorial | 6 |

| Mixed | 1 |

Materials and methods

Samples

All samples were obtained with informed consent after approval of the Institutional Review Board of the respective hospitals they were treated in, and independently reviewed by senior paediatric neuropathologists (SA, CH, ZH) according to the WHO guidelines (Kleihues et al, 2002). A total of 115 paediatric brain tumours (average 9.4±4.7 years) were analysed (Tables 1, 2a and b); 57 JPA (53 sporadic, 4 from NF1 Patients), 27 diffuse astrocytomas (grade II), 1 grade II ependymoma, 5 grade I gangliogliomas and 25 high-grade astrocytomas (HGA) were included. There were no pylomixoid variants within the JPA included within this study. All samples were taken at the time of the first surgery before further treatment, when needed. Tissues were obtained from the London/Ontario Tumor Bank, and from collaborators in Montreal, Toronto and Hungary.

DNA extraction and hybridisation, SNP analysis

DNA from frozen tumours was extracted as described previously (Wong et al, 2006). For SNP analysis, DNA (250 ng) from 40 samples was assayed with the Human Hap300-Duo (N=28) and the 610-Qad (N=16) genotyping beadchips according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). These BeadChips enable whole-genome genotyping of respectively over 300 000 and 610 000 tagSNP markers derived from the International HapMap Project (www.hapmap.org) with a mean intermaker distance of 10 and 5 kb respectively. Image intensities were extracted using Illumina's BeadScan software. Data for each BeadChip were self-normalised using information contained within the array. Penn-CNV (Wang et al, 2007) and GqCNV (D Serre et al, unpublished) algorithms were applied on the genotype data derived from the 40 LGA. Only the alterations that were detected by both algorithm and that contained more than 5 consecutive SNPs were considered in this study. They were further confirmed by visualisation in the BeadStudio.

Validation of copy number changes by quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (q-PCR) was done on an ABI-Prism 7000 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems, Bedford, MA, USA) using a SYBR Green kit (Applied Biosystems). The target locus from each tumour DNA was normalised to the reference, Line-1 as previously described (Wong et al, 2006; Supplementary Table 1).

Cell lines, antibodies and transfections

hTERT-immortalised human astrocytes (kind gift of Dr A Guha, Labbatt Brain Tumour Research Centre, Ontario, Canada) were grown and transfected with 2 μg of plasmid DNA encoding wild-type C-Myc-Braf using Fugene 6 (Roche, Mississauga, ON, Canada) as previously described (Shi et al, 2004). Unless stated otherwise, all antibodies used were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Transfected cells were used at 0, 48 and 72 h posttransfection. HIPK2 plasmids were generously provided by Dr Gabriella D'Orazi (Regina Elena Cancer Institute, Rome, Italy), and BRAF plasmids by Dr Richard Marais (Cancer Research, London, UK).

Western blot and immunofluorescence analysis

Extracts were prepared from cell pellets and western blot analysis performed on total lysates as previously described (Jabado et al, 1998; Rajasekhar et al, 2003). Cross-reactivity was visualised by ECL chemiluminescence (Amersham) on a phosphorimager. For immunofluorescence analysis images were acquired using a Retiga 1300 digital camera (QIMAGING) and a Zeiss confocal microscope.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunohistochemical analyses for phospho-Erk (pErk), were performed and the slides scored as previously described (Faury et al, 2007).

[3H]Thymidine incorporation assay

DMEM (10 ml) containing 7.4 kBq (0.2 mCi) of [methyl-3H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Europe, Freiburg, Germany; Batch 215, 65 Ci mM) were added to each microplate well. Experiments were done in triplicate at least three times with identical results.

Results

Copy number variants in 40 LGA

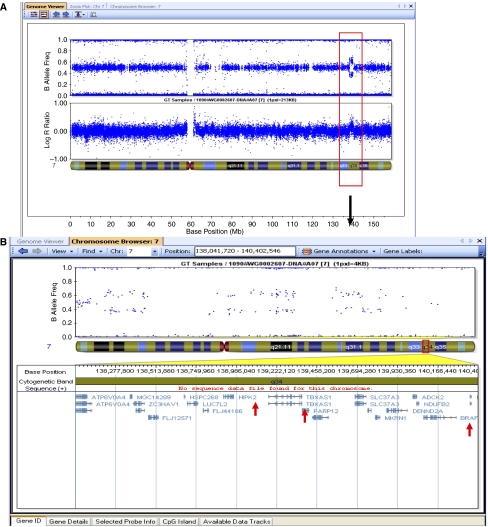

To chart genomic alterations in our sample set, we first performed a high-resolution genome-wide screen of the samples using the SNP arrays. The copy number variant (CNV) analysis of the resulting dataset generated on the Human Hap300-Duo and 610-Qad arrays gave similar results for both platforms. All samples had at least one CNV and the overall frequency of CNVs according to the chromosomal position showed that most tumours had only focal abnormalities, some of them previously reported. Most LGA did not have chromosome-wide gains or deletions, with the exception of two JPA samples, which had gains of the whole chromosome 7 (Supplementary Table 2). Regions with loss-of-heterozygosity were rarely found in LGA. We found a single region showing recurrent gain of 7q34 in 20 of 40 (50%) samples (minimal common region of gain for all tumours on chromosome 7:138380901–140119915, NCBI Build 36.3; Figure 1). The gain specifically corresponds to a chromosomal duplication, according to the Illumina Plots. A total copy number of 3 was inferred based of the logR ratio plot that is characterised by an upward deflection from 0 to 0.35 and by a split in the heterozygous allele frequencies (B-allele frequency measure) into two populations, one located at 0.67 (2 : 1 ratio) and the other at 0.33 (1 : 2 ratio; Figure 1). This gain in 7q34 is a somatic event as it was present in the tumour and not in DNA from peripheral blood taken from the same patients (n=7), thus excluding a germ-line segmental duplication (data not shown). It was not found in a set of 1363 control DNA analysed with the Illumina Human-Hap 300K platform (Hakonarson et al, 2007) or in the 25 HGA included in this study.

Figure 1.

Duplication of 7q34 visualised using BeadStudio. (A) Chromosome-wide data showing duplication at 7q34 through the increase in the log R ratio values (top) and split in the B allele frequencies (bottom) plotted for each SNP for one JPA sample (Patient 10; Table 1). (B) Zoom-in showing genes included within the region of interest. (C) Detailed view of the 7q34 locus amplified in each of the 20 JPA samples. Genes within and outside the region of interest are shown on the left. Genes we further used to validate duplication within this dataset and an additional dataset of 35 tumours are bolded.

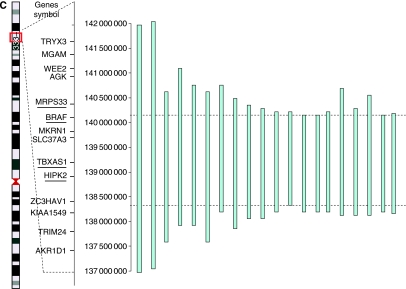

7q34 duplication involves both BRAF and HIPK2 genes and is more frequent in extrahemispheric JPA

To validate amplification of the genetic interval we identified, DNA was extracted from 17 samples analysed by SNP arrays and an additional independent set of 55 samples including 22 JPA (Tables 1, 2a and b). We performed quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) on genes included within (HIPK2 – homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2; TBXAS1 – thromboxane synthetase 1), at the edge (BRAF) and located just after (MRPS33) the interval of interest (Figure 1). The resulting profiles further confirm those obtained by SNP arrays and show that 26 of 72 samples have a detectable amplification of HIPK2, TBXAS1 and BRAF, and that most samples have normal copy number of MRPS33, which was located just outside of the genetic interval of interest on chromosome 7q34 (Figures 1 and 2; Tables 1, 2a and b). Levels of messenger RNA for BRAF and HIPK2 were also tested using quantitative RT-PCR, as previously described (Faury et al, 2007; Haque et al, 2007), in seven samples with 7q34 duplication, and were in the range of 1.7–5 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

HIPK2, TBXAS1, BRAF and MRPS33 copy number in the brain tumours included in this study. DNA qPCR-based copy number for HIPK2, TBXAS1, BRAF and MRPS33 are plotted. The cut-off for DNA copy number was set using the mean of ±2 s.d. (plotted lines) against MRPS33, which was located after the genetic interval of interest (Figure 1).

Based on concordant results we considered the amplification of HIPK2, TBXAS1 and BRAF by qPCR analysis to reflect duplication of the 7q34 region. We thus combined SNP and qPCR data, and further determined the incidence of 7q34 duplication based on histology, for example, sporadic JPA (N=53), NF1-associated JPA (N=4), diffuse astrocytomas (N=27) and the other paediatric brain tumours (N=31). 7q34 duplication was only present in sporadic JPA. Indeed, it was identified in 35 of 53 (66%) JPA, and was absent in NF1-associated JPA and the other brain tumours (Tables 1, 2a and b; Figure 2). Remarkably, this duplication was more prevalent in tumours originating from specific sites within the brain. In this regard, we found this amplification in 24 of 30 (80%) of cerebellar and 10 of 16 (62.5%) of brainstem/hypothalamic/optic-pathway JPA, whereas only 1 of 7 of hemispheric JPA had this duplication, which did not include BRAF (Tables 1, 2a and b; Figure 2; P<0.001). We also sequenced BRAF in 52 samples and found point mutations affecting the hot spot codon 600 in exon 15 of BRAF, V600E (an activating mutation previously described in melanomas and other cancers (Wan et al, 2004)) only in 1 JPA and 1 grade II ganglioglioma (Tables 1, 2a and b; Supplementary Table 3) in keeping with previous studies (Jeuken et al, 2007; Jones et al, 2008; Pfister et al, 2008).

Copy number variants in JPA without 7q34 duplication

We investigated genetic aberrations occurring specifically in JPA not carrying 7q34 duplication analysed by SNP arrays (N=10) and identified recurrent abnormalities (Table 3). Amplification of 19p13 including killer receptor inhibitory genes (KIR) genes regulating the activity of natural killer cells within the immune system was identified in 5 of 10 JPA. A recurrent region of amplification at 12p11.21 was also identified in 7 of 10 JPA and 2 of 5 grade II LGA. It includes genes with unknown function and OVOS2, a gene similar to ovostatin, a proteinase inhibitor involved in innate immune responses. These data suggest that genes involved in immune modulation may be important in the pathogenesis of another subgroup of JPA, which does not harbour 7q34 duplication.

Table 3. Genomic alterations in 10 JPA with no 7q34 duplications and 5 grade II astrocytomas.

|

Minimal common region

|

Cerebellar | Brainstem and optic | Hemispheric | Grade II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | Start | End | Nb SNP | Size (kb) | JPA | pathway JPA | JPA | astrocytoma | Genes |

| Homozygous deletions | |||||||||

| 1p36.13 | 17085956 | 17155012 | 11 | 69056 | 4 | 1 | 1 | LOC100129182, TRNAN2, CROCC | |

| 1q21.2 | 147282617 | 147427061 | 15 | 144444 | 2 | FJL12528, ECM1, FJ13544, TSRC1, MCL1, ENSA | |||

| 2p16.2 | 52995459 | 53070421 | 10 | 1 | LOC402072 | ||||

| 2q31.2 | 180123158 | 180129913 | 11 | 6755 | 1 | 1 | ZNF385B | ||

| 2q13 | 110201336 | 111021091 | 48 | 819755 | 1 | 1 | Mall, NPHP1, FLJ, RGPD6, RGPD7 | ||

| 3p21.3 | 37954886 | 37961253 | 15 | 6367 | 1 | 2 | CTDSPL | ||

| 3p21.1 | 53003023 | 53021256 | 13 | 18233 | 1 | 1 | SFMBT1 | ||

| 3q28 | 191217916 | 191221750 | 11 | 3835 | 3 | 2 | CCD50 | ||

| 4q13.2 | 69064675 | 69163188 | 36 | 98513 | 1 | 1 | 1 | UGT2B29P, UGT2B17, LOC100132651 | |

| 4q34.1 | 173218118 | 173236491 | 105 | 18373 | 2 | GALNT17 | |||

| 5p15.33 | 812485 | 873185 | 17 | 60700 | 1 | 2 | ZDHHC11B, ZDHHC11 | ||

| 5q15 | 97053242 | 97121798 | 8 | 1 | LOC391813 | ||||

| 5q35.3 | 180307066 | 180363775 | 11 | 56709 | 1 | 1 | BTNL8, LOC, BTNL3 | ||

| 7q11.22 | 67054161 | 67482237 | 54 | 1 | LOC441249 | ||||

| 8p23.1 | 12257261 | 12388979 | 16 | 131719 | 2 | ZNF705C, FAM, FAM, | |||

| 9p11.2 | 44683090 | 44770712 | 20 | 87623 | 2 | 1 | 1 | LOC | |

| 11q11 | 55124465 | 55209499 | 49 | 85035 | 1 | 1 | OR4C11, OR4P4, OR4S2, OR | ||

| 11q11 | 55447435 | 55484857 | 8 | 1 | OR5I1, OR10AF1P, OR10AK1P | ||||

| 12p13.31 | 9526879 | 9607393 | 15 | 80515 | 3 | 2 | Ovostatin | ||

| 17p11.2 | 18292126 | 18398047 | 9 | 105922 | 1 | 1 | NOS2B, FAM, LOC | ||

| 19q13.2 | 46047894 | 46075668 | 22 | 27774 | 2 | CYP2A6, CYP2A7 | |||

| 19q13.41 | 56230373 | 56263967 | 8 | 1 | KLK13 | ||||

| 20q13.2 | 52080333 | 52088118 | 23 | 7786 | 2 | BCAS1 | |||

| 21q21.3 | 26136162 | 26176988 | 8 | 1 | APP | ||||

| Chromosomal amplifications | |||||||||

| 1p31.1 | 74447282 | 74631475 | 16 | 1 | TNNI3K | ||||

| 1q43 | 234665731 | 234752676 | 84 | 86946 | 2 | EDARADD, ENO1P, LGALS8 | |||

| 2p11.2 | 86152633 | 86343699 | 20 | 1 | POLR1A, FLJ20758, IMMT, MRPL35 | ||||

| 4p12 | 47678100 | 47893952 | 50 | 139606 | 1 | NPAL1, TXK, TEC | |||

| 4q12 | 54076102 | 55611307 | 88 | 1 | FIP1L1, LNX1, CHIC2, GSH-2, PDGFRa, KIT | ||||

| 5q35.3 | 178337857 | 178528476 | 30 | 1 | GRM6, ZNF354C, LOC645944, ADAMTS2 | ||||

| 5q11.2 | 53507913 | 53670668 | 128 | 162756 | 1 | ARL15 | |||

| 6q27 | 168091860 | 168319676 | 209 | 227817 | 2 | 1 | MLLT4, LOC100128124, KIF25, FRMD1 | ||

| 8p12-8p11.23 | 38405382 | 38873687 | 41 | 2 | FGFR1, FLJ43582, TACC1 | ||||

| 8p23.1 | 8102456 | 8182850 | 26 | 80395 | 1 | FLJ10661, LOC1001 | |||

| 10q11.22 | 47007374 | 47167032 | 82 | 74264 | 2 | 1 | LOC340844, LOC728684, ANTXRL | ||

| 10q26.3 | 135116379 | 135202003 | 14 | 2 | Sprn, OR6LP2, LOC399832, OR7M1P | ||||

| 12p13.31 | 7895025 | 8014573 | 56 | 119549 | 1 | SLC2A14, LOC, NANOGP1, SLC2A3, NECAP1 | |||

| 12p11.21 | 31157554 | 31300846 | 55 | 143293 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | LOC100132881, OVOS2, LOC441632 |

| 12q14.2 | 62294703 | 62415375 | 7 | 1 | FLJ32949, LOC390338 | ||||

| 14q11.2 | 19283777 | 19493705 | 28 | 209929 | 1 | All olfactory receptors | |||

| 14q24.1-14q24.2 | 69202898 | 69470896 | 32 | 1 | KIAA0247, SFRS5, SLC10A1, RPL7AP6, SMOC1 | ||||

| 15q11.2 | 19359417 | 19523964 | 26 | 164548 | 1 | LOC, OR11J2P, OR11J5P | |||

| 15q26.3 | 99310512 | 99791921 | 204 | 481410 | 1 | LRRK1, CHSY1, SELS, SNRPA1, PCSK6 | |||

| 17q25.3 | 74877129 | 74905197 | 48 | 28069 | 1 | LOC, HRNBP3 | |||

| 19q13.31 | 47948855 | 48150403 | 26 | 201549 | 2 | Pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoproteins | |||

| 19q13.42 | 59971240 | 60054671 | 14 | 83432 | 1 | 3 | 2 | KIR2DL1-4, KIR3DP1, KIR3DL1, KIR2DS1-4 | |

| 20p13 | 1593502 | 1663448 | 41 | 69947 | 1 | LOC | |||

| 21q22.2 | 39823301 | 39835430 | 15 | 12130 | 1 | LOC | |||

| 22q11.23 | 23991725 | 24240667 | 94 | 248943 | 1 | IGLL3, LRP5L, LOC, CRYBB2P1 | |||

| 22q11.21 | 17257787 | 17388108 | 73 | 130322 | 1 | LOC, DGCR6, PRODH, DGCR5 | |||

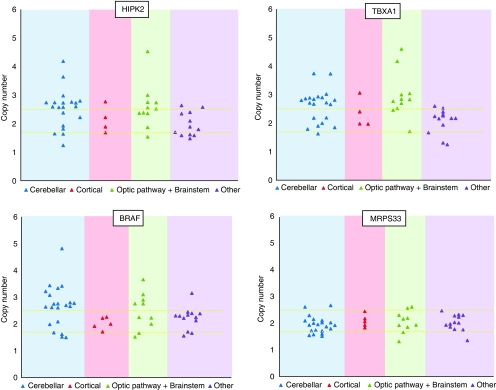

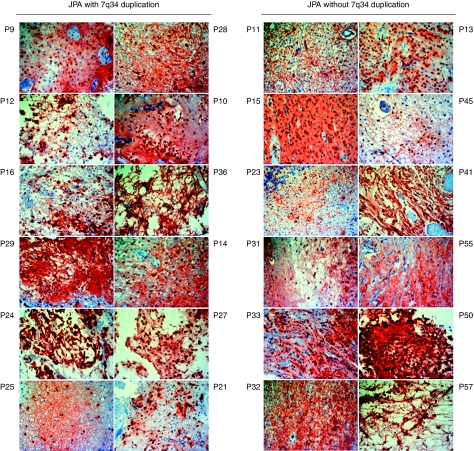

The MAPK pathway is activated in all JPA regardless of 7q34 duplication

To assess whether BRAF amplification in the absence of mutation can be correlated with increased activity of the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, we used immunohistochemical analysis based on antibodies against the phosphorylated (activated) form of ERK1–2 (pERK). Sections from samples for which we had fixed paraffin embedded slides were tested for pERK (Tables 1, 2a and b; Figure 3) immunoreactivity and scored as previously described (Faury et al, 2007). Results show that the astrocytic component of all JPA stained positively for pERK. This result indicates that the MAPK pathway is triggered in LGA, including JPA, regardless of BRAF copy number status or activating mutation.

Figure 3.

The astrocytic component of all the brain tumours included in this study show MAPK pathway activation regardless of BRAF copy number. Immunohistochemical analyses for phosphorylated ERK (pERK), used as a surrogate marker of MAPK pathway activation were performed for the 52 samples included in this study for which formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded slides were available. Sections were stained using anti-pERK followed by detection using the DAKO kit (red accounts for positive staining) and hematoxylin counterstaining. Staining intensity was scored as in (Faury et al, 2007; Haque et al, 2007). Full characteristics of samples are provided in Tables 1, 2a and b.

Functional characterisation of BRAF and/or HIPK2 overexpression in immortalised mature astrocytes

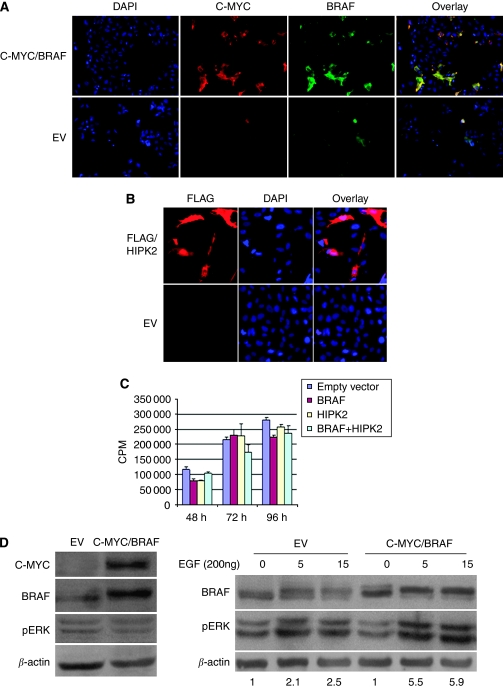

To assess the potential of increased levels of wild-type BRAF to drive increased activity of mitogenic pathways in cells of glial origin we used hTERT-immortalised astrocytes (Kamnasaran et al, 2007) as recipients of transient overexpression of genes from the 7q34 region, wild-type (WT) BRAF, HIPK2 or both. Mutant V600E BRAF was used as a positive control for transformation of astrocytes. Transfection efficiency was estimated by immunofluorescence analysis against the C-Myc and FLAG tags to be approximately ∼40–50% at 48, 72 and 96 h (Figure 4A and B). No foci of transformation or morphological changes were observed in cells transfected with WT constructs, whereas transformation foci were readily distinguishable in V600E transfectant cells. Proliferation assays revealed no change in growth of cells overexpressing of BRAF, HIPK2 or both, compared to their mock-transfected controls (Figure 4C). Similarly, overexpression of BRAF had no discernible effect on the baseline level of ERK expression or phosphorylation (Figure 4D). Indeed, in serum starved EV and C-Myc-BRAF transfectant cells pERK was similar in intensity in both settings, in keeping with previous findings in COS cells (Ciampi et al, 2005). Remarkably, exposure of BRAF overexpressing cells to ligands of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), such as transforming growth factor-α or EGF increased pERK levels by a mean of ∼5.9-fold relative to 2.3-fold in empty-vector transfectants (mean of three distinct experiments, Figure 4D). These results indicate that although BRAF overexpression may not be sufficient to drive proliferative responses of astrocytic cells it may sensitise them to exogenous growth factors.

Figure 4.

Functional analysis of BRAF and HIPK2 overexpression in hTERT-immortalised astrocytes. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of hTERT-immortalised astrocytes transfected with CMYC/BRAF or the empty vector (EV) at 48 h using an antibody recognising the C-MYC tag (red), BRAF (green) and DAPI counterstaining (blue). (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of hTERT-immortalised astrocytes transfected with FLAG/HIPK2 or the EV at 48 h using an antibody recognising the FLAG tag (red) and DAPI counterstaining (blue). (C) Proliferation of hTERT-immortalised astrocytes was assessed at 48, 72 and 96 h following transfection with mock, BRAF, HIPK2 or both genes. No difference in the rate of cell growth was observed between the transfectant cells. Results represent the median of three separate experiments performed in triplicates. (C) Total cell extracts of hTERT-immortalised astrocytes transfected with the empty-vector or C-Myc-tagged BRAF. Cells were serum starved overnight before protein lysate extraction. (D) Left panel: hTERT-immortalised astrocytes were transiently transfected with CMYC/BRAF or the empty vector. Cells were serum starved overnight and total protein lysates extracted at 48 h posttransfection. Western blot analysis for C-Myc, BRAF, phopshoERK (pERK) and β-actin (loading control) was performed. Right panel: Empty-vector (EV) and C-Myc/BRAF transfectant hTERT-immortalised astrocytes were stimulated with 200 ng of epidermal growth factor (EGF) for 5 and 15 min. Total cell lysates extracted at baseline (0) and following activation (5, 15 min) with EGF were immunoblotted using antibodies against β-actin (loading control) and phosphorylated ERK (pERK), C-Myc and BRAF. Note the shift of BRAF immunoreactive band following EGF activation which indicates phosphorylation of the kinase and increase in its molecular weight. Importantly, increase in pERK levels relative to baseline following EGF stimulation was two fold higher in C-MYC/BRAF transfectant cells than in EV transfectants. Results represent the median of three separate experiments (P<0.001).

Discussion

We show that somatic duplication of 7q34 in LGA is specific to JPA. We also establish that its prevalence varies with the site of origin within the brain of the JPA, and is more frequent in cerebellar (24 of 30 – 80%) followed by brainstem and optic pathway tumours (10 of 16 – 62.5%), whereas it is rare in hemispheric JPA (1 of 7 – 14%; Tables 1, 2a and b; Figures 1 and 2). Our analysis and the several validation steps we performed characterise this region with increased precision compared to the recently published concurrent studies, which missed either BRAF or HIPK2 (Deshmukh et al, 2008; Jones et al, 2008; Pfister et al, 2008) and confirm that 7q34 amplification includes both BRAF and HIPK2 in as many as 34 of 35 JPA samples. We identify additional genetic regions in JPA without 7q34 duplication (Table 3) and show that most genes within these regions are modulators of the immune system.

Specificity of 7q34 duplication to JPA and its prevalence in infratentorial tumours contrast with previous reports alluding that 7q34 duplication may be present in non-JPA LGA (Deshmukh et al, 2008; Pfister et al, 2008; Sievert et al, 2008) and is more frequent in non-cerebellar LGA (Pfister et al, 2008; Sievert et al, 2008). Deshmukh et al showed 7q34 duplication in 8 of 10 cerebellar JPA and further used increased HIPK2 expression on tissue microarray as a surrogate for marker for this genetic event. Other molecular events, distinct from 7q34 duplication, may lead to HIPK2 overexpression (Sombroek and Hofmann, 2009) and may account for increased HIPK2 levels in tumours other than JPA. We chose to validate the genetic interval we identified through concordant increased copy number by qPCR of three consecutive genes within it (HIPK2, TBXAS1, BRAF) in a large number of samples, and thus show specificity of 7q34 duplication to JPA. The lower resolution BAC-arrays used by Pfister et al led them to underestimate the size of the duplication (0.94 Mb instead of the ∼1.74 Mb, we and others describe) and might have led the authors to miss this duplication in a number of cerebellar JPA samples. Indeed, when we revisited data collectively published by the other groups we found that JPA within the cerebellum have the highest incidence for this duplication. In addition, in Jones et al (2008), which focused on JPA, the authors indicate 7q34 duplication might be more prevalent in infratentorial tumours, also in keeping with our data. They also show that one sample was classified as a grade II astocytoma; however, the child had prolonged disease-free survival more in keeping with a diagnosis of JPA. This misclassification might also account for the findings of 7q34 duplication in some non-JPA LGA in the study by the other groups (Deshmukh et al, 2008; Pfister et al, 2008; Sievert et al, 2008). The central review of samples by senior paediatric neuropathologists we performed has been shown to increase reproducibility of neuropathologic classification of tumours (Pollack et al, 2003) and may account for increased accuracy in our dataset. Our findings and these from recent studies alluding to the presence of different molecular signatures in sporadic JPA based on its region of origin (Sharma et al, 2007) make it tempting to speculate that, like CNS ependymoma (Taylor et al, 2005), variants of JPA might arise from a unique site-restricted progenitor cell.

RAF kinases are components of a conserved signalling pathway that regulates cellular responses to extracellular signals (Wan et al, 2004). Their role in glioma formation, and the role of the MAPK cascade they trigger, have been identified in tumour samples and further confirmed in mouse models (Jeuken et al, 2007; Pritchard et al, 2007; Lyustikman et al, 2008; Pfister et al, 2008). NF1 encodes for a Ras-GTPAse and its loss of function may lead to activation of Ras/RAF signalling and coincides with formation of indolent JPA mainly within the optic pathway. Our exploration of immortalised astrocytes show that overexpression of wild-type BRAF may not be sufficient by itself to mediate the activation of the MAPK cascade. In keeping with these data, only oncogenic BRAF mutations have been implicated in tumours of epithelial (Rajagopalan et al, 2002) and neuroectodermal origin (Brose et al, 2002; Pollock et al, 2003). 7q34 duplication in JPA was recently shown to produce novel oncogenic BRAF fusion genes with transforming capacity (Jones et al, 2008), similar to findings in radiation-associated papillary thyroid cancer (Ciampi et al, 2005) where an intrachromosomal inversion, and not duplication, let to this oncogenic event. These data indicate that wild-type BRAF would be unlikely to induce transformation. Tumours in which the duplication occurs without this in-frame fusion or in patients with trisomy of the full chromosome 7 require other mechanisms to activate BRAF and induce oncogenesis. Intriguingly, our data suggest that all JPA have active MAPK pathway regardless of 7q34 duplication (Figure 3). In keeping with the importance of the MAPK pathway in JPA genesis, two additional alternative mechanisms resulting in MAPK activation were very recently identified in JPA (Jones et al, 2009). This group studied the 10 JPA for which V600E point mutation of BRAF (2 of 44), clinical diagnosis of NF1 (3 of 44) or the common BRAF fusion following 7q34 duplication (29 of 44) could not be found (Jones et al, 2008). In one patient they found tandem duplication at 3p25 producing an in-frame oncogenic fusion between SRGAP3 and RAF1, a finding corroborated by a concurrent group on additional patients with JPA and no clinical NF1, 7q34 duplication or BRAF mutations (Forshew et al, 2009). This genetic event bears striking resemblance to the common KIAA1549 BRAF fusion event and the fusion protein includes the Raf1 kinase domain, and shows elevated kinase activity when compared with wild-type Raf1. Secondly, in one patient with JPA a novel 3 bp insertion at codon 598 in BRAF mimics the hotspot V600E mutation to produce a transforming, constitutively active BRaf kinase (Jones et al, 2009). These findings further imply that BRAF or RAF1 constitutive activation, achieved through different genetic events, converge to activate the MAPK pathway and that this pathway could be clinically targeted in all JPA.

Gains in 7q34 have been described in other cancers including ovarian cancer. However these are amplifications and not duplications and the region involved has some but no complete overlap with the one identified in JPA. Also, genetic analysis of medulloblastomas (Gilbertson and Ellison, 2008), ependymomas (Taylor et al, 2005) and high-grade astrocytomas (our data) do not identify 7q34 duplication in these tumours making this genetic event specific to JPA. Unscheduled activation of the MAPK pathway may lead to cellular senescence, which could function to limit tumour development (Courtois-Cox et al, 2006). Therefore we also postulate that oncogenic BRAF may cooperate with other, presently unknown changes, to drive formation of a subset of JPA at the same time it may drive activation of other pathways including cellular senescence. Ultimately, this may make this tumour less aggressive, similar to what is observed in melanocytes where oncogenic BRAF mutations result only in naevi formation. As complete surgical removal is the rule for cerebellar JPA, studies compiling higher numbers of JPA, occurring in other locations, are needed to establish whether 7q34 duplication is indeed associated with improved progression-free survival, as well as the biological mechanisms controlling these variables.

In summary, our studies suggest that the 7q34 region may play a site-specific role in pathogenesis of JPA and that the involvement of an active MAP kinase signalling pathway through oncogenic BRAF and other RAF family members in this process is crucial. They further emphasise the relevance of therapeutic targeting of this pathway in all JPA. To avoid misdiagnosis and adapt therapies, all infratentorial LGA should be screened by immunohistochemistry for active MAP kinase pathway (phosphorylated ERK) and further tested for the presence of 7q34 duplication, then, in its absence, 3p25 gain or BRAF mutation. Further functional evaluation of genes included within this genetic interval, others we identify herein, and others involved in the MAP kinase cascade and their correlation in larger sample sets to the site of origin, age of the patient and progression-free survival will help shed light on the pathogenesis of JPA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and the Brain Tumor Foundation (NJ, UT), the Cole Foundation (NJ), the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA) Contract No. T-04639 and the National Research and Development Fund (NKFP) Contract No. 1A/002/2004 (PH, MG, LB, ZH). K Jacob is the recipient of studentship award from CIHR and N Jabado is the recipient of a Chercheur Boursier award from Fonds de Recherche en Sante du Quebec.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bar EE, Lin A, Tihan T, Burger PC, Eberhart CG (2008) Frequent gains at chromosome 7q34 involving BRAF in pilocytic astrocytoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 67: 878–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broniscer A, Baker SJ, West AN, Fraser MM, Proko E, Kocak M, Dalton J, Zambetti GP, Ellison DW, Kun LE, Gajjar A, Gilbertson RJ, Fuller CE (2007) Clinical and molecular characteristics of malignant transformation of low-grade glioma in children. J Clin Oncol 25: 682–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose MS, Volpe P, Feldman M, Kumar M, Rishi I, Gerrero R, Einhorn E, Herlyn M, Minna J, Nicholson A, Roth JA, Albelda SM, Davies H, Cox C, Brignell G, Stephens P, Futreal PA, Wooster R, Stratton MR, Weber BL (2002) BRAF and RAS mutations in human lung cancer and melanoma. Cancer Res 62: 6997–7000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Pang JC, Ng HK, Ding M, Zhang SF, Zheng J, Liu DG, Poon WS (2000) Pilocytic astrocytomas do not show most of the genetic changes commonly seen in diffuse astrocytomas. Histopathology 37: 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciampi R, Knauf JA, Kerler R, Gandhi M, Zhu Z, Nikiforova MN, Rabes HM, Fagin JA, Nikiforov YE (2005) Oncogenic AKAP9-BRAF fusion is a novel mechanism of MAPK pathway activation in thyroid cancer. J Clin Invest 115: 94–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois-Cox S, Genther Williams SM, Reczek EE, Johnson BW, McGillicuddy LT, Johannessen CM, Hollstein PE, MacCollin M, Cichowski K (2006) A negative feedback signaling network underlies oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell 10: 459–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh H, Yeh TH, Yu J, Sharma MK, Perry A, Leonard JR, Watson MA, Gutmann DH, Nagarajan R (2008) High-resolution, dual-platform aCGH analysis reveals frequent HIPK2 amplification and increased expression in pilocytic astrocytomas. Oncogene 27: 4745–4751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faury D, Nantel A, Dunn SE, Guiot MC, Haque T, Hauser P, Garami M, Bognar L, Hanzely Z, Liberski PP, Lopez-Aguilar E, Valera ET, Tone LG, Carret AS, Del Maestro RF, Gleave M, Montes JL, Pietsch T, Albrecht S, Jabado N (2007) Molecular profiling identifies prognostic subgroups of pediatric glioblastoma and shows increased YB-1 expression in tumors. J Clin Oncol 25: 1196–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PG, Tihan T, Goldthwaite PT, Wharam MD, Carson BS, Weingart JD, Repka MX, Cohen KJ, Burger PC (2008) Outcome analysis of childhood low-grade astrocytomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51: 245–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forshew T, Tatevossian RG, Lawson AR, Ma J, Neale G, Ogunkolade BW, Jones TA, Aarum J, Dalton J, Bailey S, Chaplin T, Carter RL, Gajjar A, Broniscer A, Young BD, Ellison DW, Sheer D (2009) Activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway: a signature genetic defect in posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytomas. J Pathol 218: 172–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajjar A, Sanford RA, Heideman R, Jenkins JJ, Walter A, Li Y, Langston JW, Muhlbauer M, Boyett JM, Kun LE (1997) Low-grade astrocytoma: a decade of experience at St. Jude Children′s Research Hospital. J Clin Oncol 15: 2792–2799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson RJ, Ellison DW (2008) The origins of medulloblastoma subtypes. Annu Rev Pathol 3: 341–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill J, Laithier V, Rodriguez D, Raquin MA, Pierre-Kahn A, Kalifa C (2000) When do children with optic pathway tumours need treatment? An oncological perspective in 106 patients treated in a single centre. Eur J Pediatr 159: 692–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakonarson H, Grant SF, Bradfield JP, Marchand L, Kim CE, Glessner JT, Grabs R, Casalunovo T, Taback SP, Frackelton EC, Lawson ML, Robinson LJ, Skraban R, Lu Y, Chiavacci RM, Stanley CA, Kirsch SE, Rappaport EF, Orange JS, Monos DS, Devoto M, Qu HQ, Polychronakos C (2007) A genome-wide association study identifies KIAA0350 as a type 1 diabetes gene. Nature 448: 591–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque T, Faury D, Albrecht S, Lopez-Aguilar E, Hauser P, Garami M, Hanzely Z, Bognar L, Del Maestro RF, Atkinson J, Nantel A, Jabado N (2007) Gene expression profiling from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumors of pediatric glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 13: 6284–6292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N, Sawamura Y, Tada M, Daub DM, Janzer RC, Meagher-Villemure M, de Tribolet N, Van Meir EG (1998) Absence of p53 gene mutations in a tumor panel representative of pilocytic astrocytoma diversity using a p53 functional assay. Int J Cancer 76: 797–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabado N, Jauliac S, Pallier A, Bernard F, Fischer A, Hivroz C (1998) Sam68 association with p120GAP in CD4+ T cells is dependent on CD4 molecule expression. J Immunol 161: 2798–2803 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeuken J, van den Broecke C, Gijsen S, Boots-Sprenger S, Wesseling P (2007) RAS/RAF pathway activation in gliomas: the result of copy number gains rather than activating mutations. Acta Neuropathol 114: 121–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Backlund LM, Ichimura K, Collins VP (2008) Tandem duplication producing a novel oncogenic BRAF fusion gene defines the majority of pilocytic astrocytomas. Cancer Res 68: 8673–8677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Ichimura K, Collins VP (2009) Oncogenic RAF1 rearrangement and a novel BRAF mutation as alternatives to KIAA1549:BRAF fusion in activating the MAPK pathway in pilocytic astrocytoma. Oncogene 28: 2119–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamnasaran D, Qian B, Hawkins C, Stanford WL, Guha A (2007) GATA6 is an astrocytoma tumor suppressor gene identified by gene trapping of mouse glioma model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 8053–8058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleihues P, Louis DN, Scheithauer BW, Rorke LB, Reifenberger G, Burger PC, Cavenee WK (2002) The WHO classification of tumors of the nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61: 215–225; discussion 226–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P (2007) The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 114: 97–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyustikman Y, Momota H, Pao W, Holland EC (2008) Constitutive activation of Raf-1 induces glioma formation in mice. Neoplasia 10: 501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister S, Janzarik WG, Remke M, Ernst A, Werft W, Becker N, Toedt G, Wittmann A, Kratz C, Olbrich H, Ahmadi R, Thieme B, Joos S, Radlwimmer B, Kulozik A, Pietsch T, Herold-Mende C, Gnekow A, Reifenberger G, Korshunov A, Scheurlen W, Omran H, Lichter P (2008) BRAF gene duplication constitutes a mechanism of MAPK pathway activation in low-grade astrocytomas. J Clin Invest 118: 1739–1749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack IF, Boyett JM, Yates AJ, Burger PC, Gilles FH, Davis RL, Finlay JL (2003) The influence of central review on outcome associations in childhood malignant gliomas: results from the CCG-945 experience. Neuro Oncol 5: 197–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack IF, Mulvihill JJ (1997) Neurofibromatosis 1 and 2. Brain Pathol 7: 823–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS, Yudt LM, Stark M, Robbins CM, Moses TY, Hostetter G, Wagner U, Kakareka J, Salem G, Pohida T, Heenan P, Duray P, Kallioniemi O, Hayward NK, Trent JM, Meltzer PS (2003) High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet 33: 19–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard C, Carragher L, Aldridge V, Giblett S, Jin H, Foster C, Andreadi C, Kamata T (2007) Mouse models for BRAF-induced cancers. Biochem Soc Trans 35: 1329–1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan H, Bardelli A, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE (2002) Tumorigenesis: RAF/RAS oncogenes and mismatch-repair status. Nature 418: 934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar VK, Viale A, Socci ND, Wiedmann M, Hu X, Holland EC (2003) Oncogenic Ras and Akt signaling contribute to glioblastoma formation by differential recruitment of existing mRNAs to polysomes. Mol Cell 12: 889–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickert CH, Paulus W (2004) Comparative genomic hybridization in central and peripheral nervous system tumors of childhood and adolescence. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 63: 399–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma MK, Mansur DB, Reifenberger G, Perry A, Leonard JR, Aldape KD, Albin MG, Emnett RJ, Loeser S, Watson MA, Nagarajan R, Gutmann DH (2007) Distinct genetic signatures among pilocytic astrocytomas relate to their brain region origin. Cancer Res 67: 890–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Bao S, Maxwell JA, Reese ED, Friedman HS, Bigner DD, Wang XF, Rich JN (2004) Secreted protein acidic, rich in cysteine (SPARC), mediates cellular survival of gliomas through AKT activation. J Biol Chem 279: 52200–52209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert AJ, Jackson EM, Gai X, Hakonarson H, Judkins AR, Resnick AC, Sutton LN, Storm PB, Shaikh TH, Biegel JA (2008) Duplication of 7q34 in pediatric low-grade astrocytomas detected by high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism-based genotype arrays results in a novel BRAF fusion gene. Brain Pathol, 21 October 2008 [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sombroek D, Hofmann TG (2009) How cells switch HIPK2 on and off. Cell Death Differ 16: 187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada K, Kochi M, Saya H, Kuratsu J, Shiraishi S, Kamiryo T, Shinojima N, Ushio Y (2003) Preliminary observations on genetic alterations in pilocytic astrocytomas associated with neurofibromatosis 1. Neuro Oncol 5: 228–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MD, Poppleton H, Fuller C, Su X, Liu Y, Jensen P, Magdaleno S, Dalton J, Calabrese C, Board J, Macdonald T, Rutka J, Guha A, Gajjar A, Curran T, Gilbertson RJ (2005) Radial glia cells are candidate stem cells of ependymoma. Cancer Cell 8: 323–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan PT, Garnett MJ, Roe SM, Lee S, Niculescu-Duvaz D, Good VM, Jones CM, Marshall CJ, Springer CJ, Barford D, Marais R (2004) Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell 116: 855–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hadley D, Liu R, Glessner J, Grant SF, Hakonarson H, Bucan M (2007) PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res 17: 1665–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wemmert S, Romeike BF, Ketter R, Steudel WI, Zang KD, Urbschat S (2006) Intratumoral genetic heterogeneity in pilocytic astrocytomas revealed by CGH-analysis of microdissected tumor cells and FISH on tumor tissue sections. Int J Oncol 28: 353–360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FV, Anthony DC, Yunis EJ, Tarbell NJ, Scott RM, Schofield DE (1995) Nonrandom chromosomal gains in pilocytic astrocytomas of childhood. Hum Pathol 26: 979–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KK, Tsang YT, Chang YM, Su J, Di Francesco AM, Meco D, Riccardi R, Perlaky L, Dauser RC, Adesina A, Bhattacharjee M, Chintagumpala M, Lau CC (2006) Genome-wide allelic imbalance analysis of pediatric gliomas by single nucleotide polymorphic allele array. Cancer Res 66: 11172–11178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.