Sir,

We read with great interest the recent study by Pabst et al (2009) disclosing that there is relevant prognostic heterogeneity within AML patients with CEBPA mutations and only CEBPA double mutations (CEBPAdouble-mut), but not single mutations (CEBPAsingle-mut), are associated with favourable prognosis in the AML patients. However, the reason why CEBPAsingle-mut patients have a poorer outcome than CEBPAdouble-mut patients remains unclear and a comprehensive study to evaluate the biological difference between these two groups is still lacking.

In this study, we investigated the prevalence and clinical relevance of CEBPAdouble-mut and CEBPAsingle-mut and their association with other genetic changes in a large cohort of 543 consecutive de novo AML patients at the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of NTUH; written informed consents were obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. CEBPA mutations were detected by genomic-DNA PCR and direct sequencing as described earlier (Lin et al, 2005). Mutational analyses of FLT3/ITD, FLT3/TKD N-RAS, K-RAS, NPM1, CEBPA, KIT, AML1 and MLL/PTD were carried out as previously described (Hou et al, 2008).

Among the 543 AML patients recruited, we identified 71 (13.1%) patients with CEBPA mutations, including 47 CEBPAdouble-mut and 24 CEBPAsingle-mut. Compared with patients who have CEBPAdouble-mut, those with CEBPAsingle-mut had lower incidences to express HLA-DR (65 vs 96%, P=0.0014), CD7 (44 vs 79%, P=0.006) and CD15 (35 vs 85%, P<0.0001), but a higher incidence to express CD56 (35 vs 11%, P=0.038) on leukemia cells. Apart from this, there were no differences in other clinical parameters including age, sex, haemogram, LDH level, FAB subtype and karyotype between these two groups. No matter CEBPAsingle-mut or CEBPAdouble-mut, the mutation disappeared at complete remission in all patients who had paired bone marrow samples for analysis and reappeared at relapse.

Patients with CEBPAsingle-mut had a higher incidence of NPM1 mutation than those with CEBPAdouble-mut (4/24, 16.7 vs 0%, P=0.0109). There was also a higher incidence of concurrent mutation of FLT3/ITD, FLT3/TKD, AML1/RUNX1 or MLL/PTD in CEBPAsingle-mut patients than in CEBPAdouble-mut patients (20.8 vs 10.6%, 12.5 vs 4.3%, 8.3 vs 2.1% and 4.2 vs 0%, respectively), but the difference did not reach statistical significance. However, when combined together, simultaneous alteration of any one of these four mutations occurred more frequently in the former group than in the latter (37.5 vs 14.9%, P=0.039). More intriguingly, all four CEBPAsingle-mut patients with NPM1 mutation also simultaneously had FLT3/ITD (2 patients), FLT3/TKD (1 patient), or both (1 patient).

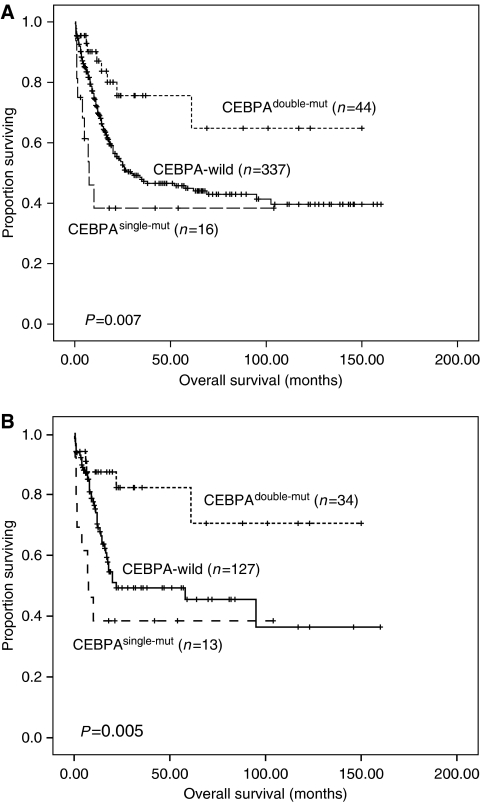

In terms of outcome, CEBPAdouble-mut patients had a higher complete remission rate than CEBPAsingle-mut patients (91 vs 56.3%, P=0.0051). The patients with CEBPAdouble-mut had a significant longer overall survival (OS) than those with CEBPAwild or CEBPAsingle-mut (median: not reached vs 29.8 months and 7.5 months; P=0.013 and P=0.001, respectively; among 3 groups, P=0.007, Figure 1A). The same was also true for disease-free survival (DFS) (median: 59 months vs 8 months and 4 months; P=0.016 and P=0.027, respectively; among 3 groups, P=0.037). Among the subgroup of patients with normal karyotype, the differences in OS and DFS between CEBPAdouble-mut and CEBPAsingle-mut patients were still obvious (P=0.002 and P=0.019, respectively, Figure 1B). The multivariate analysis clearly identified CEBPAdouble-mut, but not CEBPAsingle-mut as an independent prognostic factor for OS and DFS (hazard ratio 0.362, 95% CI 0.182–0.721, P=0.004 and hazard ratio 0.426, 95% CI 0.263–0.691, P=0.001, respectively, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of overall survival (OS) stratified by different status of CEBPA mutation at diagnosis among total patients (A) and in the subgroup of patients with normal karyotype (B). Only patients receiving standard chemotherapy were enrolled into survival analysis. Among total patients, P-value for OS of CEBPAdouble-mut vs CEBPAwild patients was 0.013, for CEBPAdouble-mut vs CEBPAsingle-mut patients, 0.001, and among three groups, 0.007 (A). In the subgroup of patients with normal karyotype, P-value for OS of CEBPAdouble-mut vs CEBPAwild patients was 0.01, for CEBPAdouble-mut vs CEBPAsingle-mut patients was 0.002 and among three groups it was 0.005 (B).

Table 1. Multivariate analysis for overall and disease-free survivala.

| Overall survival | Disease-free survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value |

| CEBPA single-mut | 1.614 (0.743–3.508) | 0.227 | 1.164 (0.630–2.149) | 0.629 |

| CEBPA double-mut | 0.362 (0.182–0.721) | 0.004 | 0.426 (0.263–0.691) | 0.001 |

| Karyotype | 2.388 (1.774–3.215) | <0.001 | 2.387 (1.899–3.002) | <0.001 |

| Ageb | 2.741 (1.959–3.836) | <0.001 | 1.488 (1.137–1.948) | 0.004 |

| Sexc | 0.937 (0.670–1.311) | 0.704 | 1.107 (0.848–1.445) | 0.456 |

| WBCd | 1.524 (1.051–2,209) | 0.026 | 1.396 (1.031–1.890) | 0.031 |

| FLT3/ITD | 1.798 (1.232–2.624) | 0.002 | 1.843 (1.350–2.515) | <0.001 |

| AML1/RUNX1 | 1.755 (1.036–2.972) | 0.036 | 1.410 (0.909–2.187) | 0.125 |

| NPM1 | 0.500 (0.317–0.789) | 0.003 | 0.482 (0.332–0.699) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio.

Including 397 patients who received standard chemotherapy. Those patients who did not receive chemotherapy or only low dose chemotherapy were excluded.

Age greater than 50-years old vs less than 50-years old.

Male vs female.

WBC greater than 50 × 109/l vs less than 50 × 109/l.

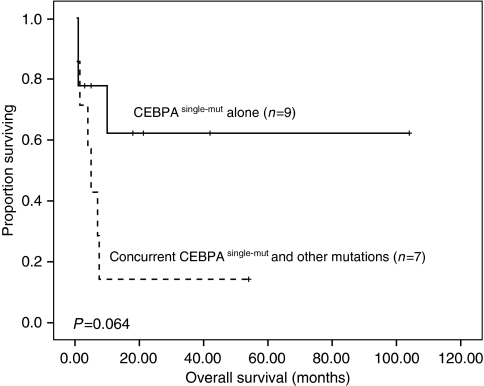

From the above findings, we hypothesise that the close association of CEBPAsingle-mut with CD56 expression (Raspadori et al, 2001) and other poor-risk genetic alterations, such as FLT3/ITD, FLT3/TKD, MLL/PTD and AML1/RUNX1, (Schnittger et al, 2000; Harada et al, 2004; Whitman et al, 2008) may partially explain why CEBPAsingle-mut predisposes to inferior outcome than CEBPAdouble-mut. We also observed a trend of shorter OS in CEBPAsingle-mut patients who had concurrent FLT3/ITD, FLT3/TKD,MLL/PTD or AML1/RUNX1 mutation than those who did not (P=0.064, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of overall survival (OS) in the CEBPAsingle−mut patients with and without concurrent FLT3/ITD, FLT3/TKD, MLL/PTD or AML1/RUNX1 mutation.

In summary, about one-third of patients with CEBPA mutations had CEBPAsingle-mut, which were closely associated with CD56 expression but inversely correlated with HLA-DR, CD7 and CD15 expression. Compared with patients who have CEBPAdouble-mut, those with CEBPAsingle-mut had a higher incidence of concurrent FLT3/ITD, FLT3/TKD, MLL/PTD or AML1/RUNX1 mutation and had a poorer prognosis. This study provides evidences independently from previous ones, stressing the differences in biological characteristics between CEBPAsingle-mut and CEBPAdouble-mut AML and their possible prognostic implication. Further studies are necessary to clarify whether the close association of CEBPAsingle-mut with CD56 expression and other poor-risk gene alterations contributes to the poorer outcome of this group of patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harada H, Harada Y, Niimi H, Kyo T, Kimura A, Inaba T (2004) High incidence of somatic mutations in the AML1/RUNX1 gene in myelodysplastic syndrome and low blast percentage myeloid leukemia with myelodysplasia. Blood 103(6): 2316–2324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou HA, Chou WC, Lin LI, Chen CY, Tang JL, Tseng MH, Huang CF, Chiou RJ, Lee FY, Liu MC, Tien HF (2008) Characterization of acute myeloid leukemia with PTPN11 mutation: the mutation is closely associated with NPM1 mutation but inversely related to FLT3/ITD. Leukemia 22(5): 1075–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LI, Chen CY, Lin DT, Tsay W, Tang JL, Yeh YC, Shen HL, Su FH, Yao M, Huang SY, Tien HF (2005) Characterization of CEBPA mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: most patients with CEBPA mutations have biallelic mutations and show a distinct immunophenotype of the leukemic cells. Clin Cancer Res 11(4): 1372–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst T, Eyholzer M, Fos J, Mueller BU (2009) Heterogeneity within AML with CEBPA mutations; only CEBPA double mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations are associated with favourable prognosis. Br J Cancer 100(8): 1343–1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raspadori D, Damiani D, Lenoci M, Rondelli D, Testoni N, Nardi G, Sestigiani C, Mariotti C, Birtolo S, Tozzi M, Lauria F (2001) CD56 antigenic expression in acute myeloid leukemia identifies patients with poor clinical prognosis. Leukemia 15(8): 1161–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Kinkelin U, Schoch C, Heinecke A, Haase D, Haferlach T, Büchner T, Wörmann B, Hiddemann W, Griesinger F (2000) Screening for MLL tandem duplication in 387 unselected patients with AML identify a prognostically unfavorable subset of AML. Leukemia 14(5): 796–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman SP, Ruppert AS, Radmacher MD, Mrózek K, Paschka P, Langer C, Baldus CD, Wen J, Racke F, Powell BL, Kolitz JE, Larson RA, Caligiuri MA, Marcucci G, Bloomfield CD (2008) FLT3 D835/I836 mutations are associated with poor disease-free survival and a distinct gene-expression signature among younger adults with de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia lacking FLT3 internal tandem duplications. Blood 111(3): 1552–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]