Abstract

Background

Prior studies in the USA have reported higher rates of mental disorders among persons with arthritis but no cross-national studies have been conducted. In this study the prevalence of specific mental disorders among persons with arthritis was estimated and their association with arthritis across diverse countries assessed.

Method

The study was a series of cross-sectional population sample surveys. Eighteen population surveys of household-residing adults were carried out in 17 countries in different regions of the world. Most were carried out between 2001 and 2002, but others were completed as late as 2007. Mental disorders were assessed with the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health–Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI). Arthritis was ascertained by self-report. The association of anxiety disorders, mood disorders and alcohol use disorders with arthritis was assessed, controlling for age and sex. Prevalence rates for specific mental disorders among persons with and without arthritis were calculated and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals were used to estimate the association.

Results

After adjusting for age and sex, specific mood and anxiety disorders occurred among persons with arthritis at higher rates than among persons without arthritis. Alcohol abuse/dependence showed a weaker and less consistent association with arthritis. The pooled estimates of the age- and sex-adjusted ORs were about 1.9 for mood disorders and for anxiety disorders and about 1.5 for alcohol abuse/dependence among persons with versus without arthritis. The pattern of association between specific mood and anxiety disorders and arthritis was similar across countries.

Conclusions

Mood and anxiety disorders occur with greater frequency among persons with arthritis than those without arthritis across diverse countries. The strength of association of specific mood and anxiety disorders with arthritis was generally consistent across disorders and across countries.

Keywords: Arthritis, mental disorders, cross-sectional

Introduction

Studies conducted in many countries worldwide have found arthritis to be common in the general population, especially among older adults (Carmona et al. 2001; CDC, 2001; Zhang et al. 2001; Reginster, 2002; PRC, 2003; Stang et al. 2006). Among the elderly, about one-third to more than half report arthritis or chronic joint symptoms (Helmick et al. 1995; CDC, 2001; Mili et al. 2002; Mannoni et al. 2003; Stang et al. 2006). Arthritis is found to be more common among women than men in most of these studies, and the prevalence of arthritis increases with age in both male and female patients (Mikkelsen et al. 1967; Cunningham & Kelsey, 1984; Felson et al. 1987; van Saase et al. 1989; Reginster, 2002). In a community-based survey, the incidence and prevalence of disease increased 2- to 10-fold from 30 to 65 years of age (Oliveria et al. 1995). Arthritis is also known to be associated with significant disability and economic burden. Arthritis accounts for one-eighth of all restricted activity days in the US adult population, causes large health-care and work disability costs, and leads to notable decrements in social role performance (Guccione et al. 1994; Yelin, 1995; Yelin & Callahan, 1995; Lawrence et al. 1998; Dunlop et al. 2004; Stang et al. 2006).

Studies have found a relationship between pain and depression (Gureje et al. 1998, 2007; Demyttenaere et al. 2006). Prior research in developed countries has also found that persons with arthritis, mainly osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, are more likely to experience depressive illness (Dickens et al. 2003; John et al. 2003; Lowe et al. 2004; Ang et al. 2005). Such co-morbidity is found to be associated with increased disability, use of health services and mortality risk (Vali & Walkup, 1998; Khongsaengdao et al. 2000; Oslin et al. 2002; Dickens et al. 2003; Kessler et al. 2003; Lowe et al. 2004; Ang et al. 2005). Until recently, the association of arthritis with other mental disorders, including anxiety disorders and substance use disorders, has received only limited attention. Stang et al. (2006) analyzed data from the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey Replication and found that arthritis was associated with increased prevalence of both mood and anxiety disorders.

Using data from 18 surveys participating in the World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys, information regarding the occurrence of a number of mental disorders among persons reporting arthritis was explored for the first time. The objectives of this study were: (1) to estimate the prevalence of specific mood disorders, anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders among persons with arthritis in diverse countries; (2) to determine which kinds of mental disorder are most strongly associated with arthritis after controlling for age and sex; and (3) to assess whether the associations of specific mental disorders with arthritis are consistent across adult populations in different countries in Europe, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, Africa and the South Pacific. This study assessed whether the association between chronic pain and mental disorders is also observed for arthritis, and whether arthritis is also associated with a range of anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders. It provides the first cross-national comparison from a global perspective of the occurrence of mood, anxiety and alcohol use disorders among persons with arthritis in general population samples.

Method

Samples

Eighteen surveys were carried out in 17 countries in the Americas (Colombia, Mexico, the USA), Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, Ukraine), the Middle East (Israel, Lebanon), Africa (Nigeria, South Africa), Asia (Japan, separate surveys in Beijing and Shanghai in the People’s Republic of China), and the South Pacific (New Zealand). Most of the 18 surveys were carried out between 2001 and 2002, but others were completed as late as 2007. Field work duration ranged from 3 to 33 months, with about half of the studies being completed in the 12-month range. An effort was made to recruit as many countries as possible into the initiative. The final set of countries was determined by the availability of collaborators who were able to obtain funding for the survey. All surveys were based on multi-stage, clustered area probability household samples. All interviews were carried out face-to-face by trained lay interviewers. The six Western European surveys were carried out jointly (ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators, 2004). Sample sizes ranged from 2372 (The Netherlands) to 12 992 (New Zealand), with a total of 85 088 participating adults. Response rates range from 46% (France) to 88% (Colombia), with a weighted average of 71%.

Internal subsampling was used to reduce respondent burden by dividing the interview into two parts. Part 1 included the core diagnostic assessment of mental disorders. Part 2 included additional information relevant to a wide range of survey aims, including assessment of chronic physical conditions. All respondents completed Part 1. All Part 1 respondents who met criteria for any mental disorder and a probability sample of other respondents were administered Part 2 with two exceptions: in Israel, where all respondents were recruited as one sample and only one long version of the questionnaire, including both diagnostic assessment and additional relevant information, was used; and in Lebanon, where only a subsample of Part 2 (random 20%) was asked for chronic physical conditions. A total number of 42 697 respondents completed Part 2 and questions about chronic physical condition were included for analysis of arthritis and mental disorder co-morbidity.

Part 2 respondents were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection for Part 2 of the interview to adjust for differential sampling. Analyses in this article were based on the weighted Part 2 sample. Additional weights were used to adjust for differential probabilities of selection within households, and post-stratification to adjust weighted sample distributions for the 2000 census table (age, sex and education) was used to ensure that the joint distribution of a set of post-stratifying variables matches the known local population distribution.

Training and field procedures

The central WMH staff trained bilingual supervisors in each country. Consistent interviewer training documents and procedures were used across surveys. The WHO translation protocol was used to translate instruments and training materials. Two surveys were carried out in bilingual form (Dutch and French in Belgium; Russian and Ukrainian in Ukraine). In Israel, three languages (Hebrew, Russian and Arabic) were used. In Nigeria, interviews were conducted in four languages (Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo and Efik), using the dominant language in the region where the survey was carried out. Others were carried out exclusively in the country’s official language. Persons who could not speak these languages were excluded. Standardized descriptions of the goals and procedures of the study, data uses and protection, and the rights of respondents were provided in both written and verbal form to all potentially eligible respondents before obtaining verbal informed consent for participation in the survey. Quality control protocols, described in more detail in Kessler et al. (2004), were standardized across countries to check on interviewer accuracy and to specify data cleaning and coding procedures. The institutional review board of the organization that coordinated the survey in each country approved and monitored compliance with procedures for obtaining informed consent and protecting human subjects.

Mental disorder status

All surveys used the WMH Survey version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI; Kessler & Ustun, 2004), a fully structured diagnostic interview, to assess disorders and treatment. Disorders considered in this study include anxiety disorders [generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and social phobia], mood disorders (dysthymia and major depressive disorder) and substance disorders (alcohol and drug abuse and dependence). Disorders were assessed using DSM-IV definitions and criteria (APA, 1994). CIDI organic exclusion rules were imposed in making all diagnoses. Methodological evidence collected in the WHO-CIDI field trials and later clinical calibration studies showed that all the disorders considered here were assessed with acceptable reliability and validity both in the original CIDI (Wittchen, 1994) and in the original version of the WMH-CIDI (Kessler et al. 2004). Studies of cross-national comparability in the validity of the WMH-CIDI are under way. Clinical reappraisal in probability subsamples of the WMH surveys in France, Italy, Spain and the USA found moderate to good individual-level CIDI–SCID concordance for lifetime prevalence estimates of most disorders (Haro et al. 2006).

Arthritis status

In a series of validated questions about chronic conditions adapted from the US Health Interview Survey (National Center for Health Statistics, 1994), respondents were asked about the presence of selected chronic conditions. The question about arthritis was asked in two different forms depending on the country. In Nigeria, Lebanon, Beijing and Shanghai PRC, South Africa and Ukraine, respondents were asked whether they had experienced ‘arthritis or rheumatism’ in the prior 12 months. In the remaining surveys, respondents were asked if they had ever had ‘arthritis or rheumatism’. The 12-month report of arthritis and the lifetime report of arthritis were compared for the six ESEMeD countries that had both. The lifetime report of arthritis is reported as being present in the past 12 months from 53% to 80% of the time, averaging over 60% of the time. Because of the chronic nature of this disease, these two versions were combined and the lifetime definition was used.

In a study looking at the validity of self-reported arthritis when compared to information from medical records on diagnosis or treatment for arthritis in the prior 3 years, over 90% of cases were confirmed (Lin et al. 2003). Again, in the US National Health Interview Survey, arthritis self-report showed moderate agreement with medical records data (k = 0.40), with many persons reporting arthritis not receiving medical care for their condition (National Center for Health Statistics, 1994). However, a lower agreement (k = 0.3) between self-report arthritis and general practitioner information among elderly patients in three culturally distinct geographical areas of The Netherlands was reported by Kriegsman et al. (1996). The Framingham study delineated the degree of discrepancy between radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis and self-reported symptoms related to the severity of the disease (Felson et al. 1987). Neither medical records nor radiographic examinations are considered to be the gold standard for assessing the validity of ascertainment of arthritis in a community survey.

Analytical methods

In this paper we report the prevalence rates for specific mental disorders among persons with and without arthritis. Odds ratios (ORs) for the association of each mental disorder with arthritis were estimated for each survey adjusting for age and sex. Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals (CIs) for the ORs were estimated using the Taylor series method (Wolter, 1985) with SUDAAN (2002) to adjust for clustering and weighting.

A pooled estimate of the ORs and their standard errors was developed to describe the association of each mental disorder with arthritis across the surveys. The pooled estimate of the OR was weighted by the inverse of the variance of the estimate for each survey. The CIs for the pooled estimates of the ORs were estimated. For each association of a specific mental disorder with arthritis, we assessed whether the heterogeneity of the OR estimates across surveys was greater than that expected by chance. Because six out of the seven heterogeneity tests were nonsignificant, we concluded that pooled estimates of the ORs, and CIs for the pooled estimates, could be appropriately reported. Pooled estimates of mental disorder prevalence rates were not reported because of the large variation in mental disorder prevalence rates across the surveys.

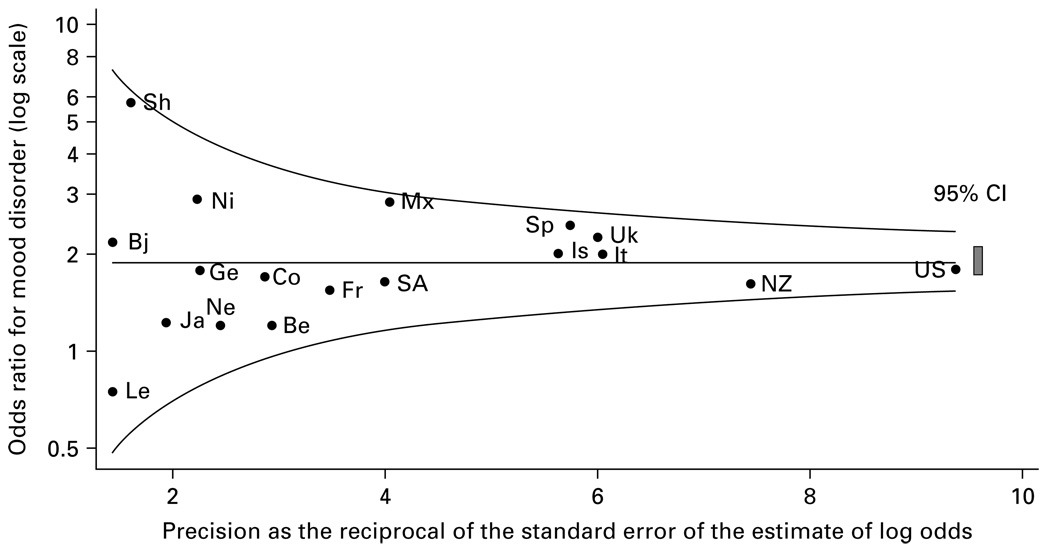

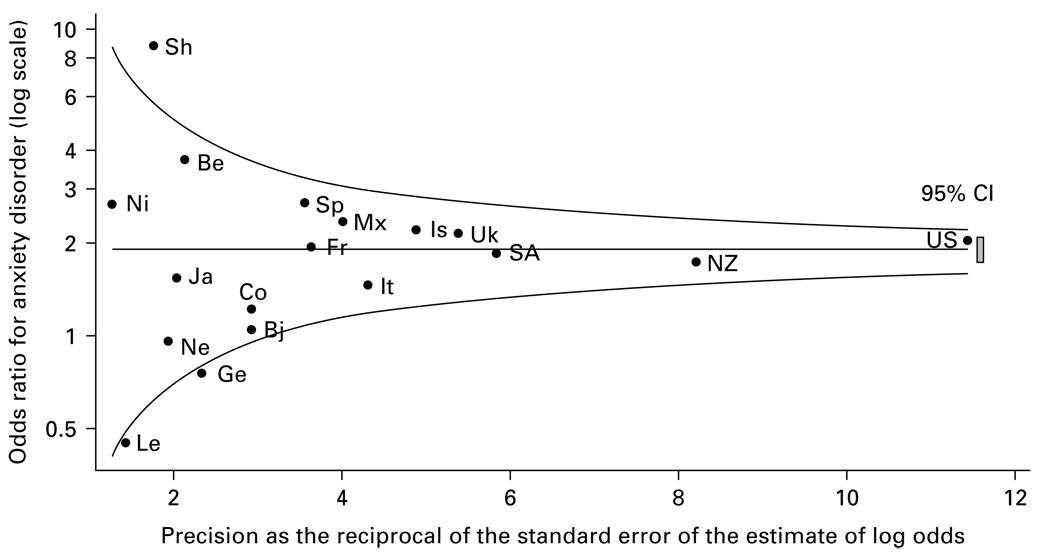

We also calculated adjusted ORs assessing the association of each mood disorder (major depressive disorder or dysthymia) and each anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety disorders, panic/agoraphobia, social phobia or PTSD) with arthritis. A pooled estimate of these ORs across surveys was also estimated. These ORs, and the pooled estimate, are displayed for each survey using a funnel graph (Bird et al. 2005), which plots the OR for each survey on a log scale (y axis) against the precision of the estimate of each OR (x axis). Precision is the reciprocal of the standard error of the OR estimate. Precision increases as the standard error of the estimate becomes smaller. The ‘funnel’ in these graphs shows the band that survey-specific estimates fall within if their 95% CIs include the pooled estimate. Each survey’s estimate was plotted on the funnel graph, showing whether the pooled estimate fell within the 95% CI of each survey’s OR estimate. On this graph, the less precise estimates are to the left (where the funnel is wider), and the more precise estimates are to the right (where the funnel is narrower). These graphs provide a visual summary of the association of any mood disorder and any anxiety disorder with arthritis across the participating surveys.

Results

Sample characteristics and prevalence of arthritis

The samples showed substantial cross-national differences. As expected, persons tended to be older and better educated in the developed than developing countries (Table 1). Self-reported arthritis was common in all of the participating countries, with prevalence rates ranging from 6.1% in Colombia to 29.2% in France (Table 1). Prevalence rates were generally higher in the European countries, the USA and New Zealand than elsewhere. Consistent with prior epidemiological data, in all of the surveys: women were more likely to report arthritis than men; less educated persons were more likely to report arthritis than those with higher levels of education; and prevalence increased with age (data not shown).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and arthritis prevalence (n = 42697)

| Arthritis prevalenceb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | National sample (n) | Mean agea (years) | % ≥60 years | % women | Education: secondary or greater | n | Weighted % |

| Americas | |||||||

| Colombia | 2381 | 36.6 | 5.3 | 54.5 | 46.4 | 184 | 6.1 |

| Mexico | 2362 | 35.2 | 5.2 | 52.3 | 31.4 | 229 | 7.5 |

| USA | 5692 | 45.0 | 21.2 | 53.0 | 83.2 | 1588 | 27.3 |

| Asia and South Pacific | |||||||

| Japan | 887 | 51.4 | 34.9 | 53.7 | 70.0 | 117 | 10.2 |

| Beijing, PRC | 914 | 39.8 | 15.6 | 47.5 | 61.4 | 111 | 8.6 |

| Shanghai, PRC | 714 | 42.9 | 18.7 | 48.1 | 46.8 | 114 | 15.3 |

| New Zealand | 7312 | 44.6 | 20.7 | 52.2 | 60.4 | 1474 | 19.6 |

| Europe | |||||||

| Belgium | 1043 | 46.9 | 27.3 | 51.7 | 69.7 | 227 | 20.3 |

| France | 1436 | 46.3 | 26.5 | 52.2 | N.A. | 432 | 29.2 |

| Germany | 1323 | 48.2 | 30.6 | 51.7 | 96.4 | 151 | 11.9 |

| Italy | 1779 | 47.7 | 29.2 | 52.0 | 39.5 | 510 | 26.9 |

| Netherlands | 1094 | 45.0 | 22.7 | 50.9 | 69.7 | 134 | 10.7 |

| Spain | 2121 | 45.5 | 25.5 | 51.4 | 41.7 | 617 | 21.4 |

| Ukraine | 1720 | 46.1 | 27.3 | 55.1 | 79.5 | 479 | 20.3 |

| Middle East and Africa | |||||||

| Lebanon | 602c | 40.3 | 15.3 | 48.1 | 40.5 | 57 | 6.9 |

| Nigeria | 2143 | 35.8 | 9.7 | 51.0 | 35.6 | 469 | 16.9 |

| Israel | 4859 | 44.4 | 20.3 | 51.9 | 78.3 | 496 | 9.7 |

| South Africa | 4315 | 37.1 | 8.8 | 53.6 | 38.9 | 453 | 10.1 |

Age range ≥18 years, except for Colombia and Mexico (18–65 years), Japan (≥20 years) and Israel (≥21 years).

Lifetime prevalence reported, except for Beijing, Shanghai, Lebanon, Nigeria, Ukraine and South Africa (12-month prevalence). There is no consistent difference in prevalence rates between the countries reporting 12-month and lifetime rates.

Random 20% of Part 2 sample.

Mood disorders and arthritis

Major depression was common among persons with arthritis (Table 2). Prevalence estimates fell in the 5–10% range in two-thirds of the countries. The prevalence rates of dysthymia were lower than major depression. Comparison of the prevalence rates of major depression and dysthymia among persons with versus without arthritis showed small absolute differences in many countries, with eight countries showing slightly lower prevalence rates of either major depression or dysthymia among persons with arthritis. Prevalence of mood disorders and arthritis varies according to age and gender. Age and sex were adjusted in assessing the association of arthritis and mood disorders.

Table 2.

Prevalence (%) of mood disorders among persons with versus without arthritisa

| Major depression |

Dysthymia |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | No arthritis | Arthritis | OR (95% CI) adjusted | No arthritis | Arthritis | OR (95% CI) adjusted |

| Colombia | 6.0 | 9.3 | 1.7 (0.8–3.4) | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 (0.4–4.4) |

| Mexico | 3.7 | 10.2 | 2.9 (1.8–4.7)* | 0.8 | 2.0 | 2.2 (0.7–7.0) |

| USA | 7.9 | 9.3 | 1.8 (1.4–2.2)* | 1.8 | 3.6 | 2.4 (1.9–3.1)* |

| Japan | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.3 (0.4–3.5) | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.2 (0.0–1.5) |

| Beijing, PRC | 2.2 | 3.9 | 2.1 (0.5–8.8) | 0.3 | 1.1 | 3.0 (0.7–12.7) |

| Shanghai, PRC | 1.0 | 5.7 | 6.4 (1.8–22.4)* | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.0 (0.1–7.7) |

| New Zealand | 6.7 | 6.2 | 1.6 (1.2–2.1)* | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.9 (1.3–2.9)* |

| Belgium | 5.8 | 4.7 | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 1.1 | 2.1 | 1.4 (0.5–4.1) |

| France | 6.2 | 5.9 | 1.5 (0.9–2.7) | 1.2 | 2.7 | 1.6 (0.6–4.6) |

| Germany | 3.0 | 3.8 | 1.9 (0.8–4.7) | 0.7 | 2.2 | 3.3 (0.6–17.6) |

| Italy | 2.4 | 5.1 | 2.0 (1.4–2.7)* | 0.7 | 2.1 | 2.0 (1.0–3.9)* |

| Netherlands | 5.3 | 5.0 | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.4 (0.4–4.5) |

| Spain | 3.3 | 6.8 | 2.3 (1.7–3.0)* | 0.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 (1.7–5.9)* |

| Ukraine | 7.0 | 19.2 | 2.3 (1.6–3.3)* | 2.5 | 10.6 | 2.9 (1.9–4.3)* |

| Lebanon | 1.9 | 1.4 | 0.7 (0.2–3.0) | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.3 (0.2–9.7) |

| Nigeria | 0.9 | 2.2 | 2.9 (1.2–7.0)* | 0.1 | 0.6 | 8.6 (1.2–64.5)* |

| Israel | 5.6 | 10.5 | 2.0 (1.4–2.8)* | 1.0 | 3.9 | 3.8(2.0–7.0)* |

| South Africa | 4.5 | 7.6 | 1.6 (1.0–2.6) | 0.1 | 0.0 | N.E. |

| Pooled OR | – | – | 1.9 (1.7–2.1)* | – | – | 2.4 (2.0–2.7)* |

OR, Odds ratio (adjusted for age and sex); CI, confidence interval; N.E., non-estimable; –, information not available.

Country not included if less than 25 respondents have the physical condition.

p ≤ 0.05.

As shown in Table 2, age- and sex-adjusted ORs and their 95% CIs measuring the association of major depression with arthritis were greater than one for 16 of the 18 surveys and significantly greater than one for nine of the 18 surveys at a 0.05 significance level. As the 18 surveys differed in sample size and number of cases of arthritis and depression identified, it is not surprising that ORs for many of the individual surveys were not significantly greater than one. This may be explained by both limitations of statistical power of single surveys and random variation in the OR estimates across the single surveys. The OR estimates for dysthymia showed a similar pattern. We assessed whether the variability in the OR estimates across the different surveys was greater than that expected by chance. The test of heterogeneity was non-significant for both major depression (p = 0.20) and dysthymia (p = 0.35), making it appropriate to report a pooled estimate. The pooled estimate of the ORs of major depression among persons with versus without arthritis was 1.9 (95% CI 1.7–2.1), while the pooled estimate of the ORs of dysthymia among persons with arthritis was 2.4 (95% CI 2.0–2.7), indicating a significant overall association of arthritis with both major depression and dysthymia, after adjusting for age and sex. Given the limitations of statistical power and the random variation of estimates across the single surveys, the fact that only about half of the surveys found ORs that were significantly greater than one does not support an inference that arthritis and depression (or dysthymia) were associated in some surveys but not in others. Rather, it suggests that the individual surveys may not have been adequately powered to detect an OR for this association in the moderate range.

Fig. 1 shows the funnel graph of the age- and sex-adjusted ORs for mood disorder (major depression and dysthymia combined) in all 18 countries. In this graph, the OR was plotted on a log scale. The funnel lines show the band indicating the limit of the 95% CI of a survey estimate in relation to the pooled estimates, given the precision of the survey estimate. Most of the OR estimates clustered close to the pooled estimate of 1.9. All of the pooled estimates fell within the 95% CIs of the individual survey estimates, with those at the end of the left side of the funnel tending to have the lowest precision. These results support the conclusion that persons with arthritis are more likely to experience mood disorders than otherwise comparable persons without arthritis.

Fig. 1.

Odds ratios (age- and sex-adjusted) for mood disorder for persons with versus without arthritis. Be, Belgium; Bj, Beijing; Co, Colombia; Fr, France; G, Germany; Is, Israel; It, Italy; Ja, Japan; Le, Lebanon; Mx, Mexico; Ne, Netherlands; Ni, Nigeria; NZ, New Zealand; SA, South Africa; Sh, Shanghai; Sp, Spain; Uk, Ukraine; US, United States.

Anxiety disorders and arthritis

Across the surveys, the specific anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic/agoraphobia, social phobia and PTSD) were less prevalent among persons with arthritis than major depression (Table 3), reflecting the lower prevalence of these disorders in general. Because social phobia and PTSD were relatively less common, it was not possible to estimate ORs for their association with arthritis for several countries. Given the relatively small sample sizes of these specific anxiety disorders, it is not surprising that the OR estimates were significantly greater than one for some surveys but not for others, even when the OR estimates were consistent with the pooled estimate. The heterogeneity tests for the ORs were non-significant for generalized anxiety disorder (p = 0.44), agoraphobia/panic (p = 0.44) and PTSD (p = 0.11), but the heterogeneity test for social phobia was significant (p = 0.03). Given the limited number of cases available in each survey, the pooled estimate of the ORs provides a more precise estimate of the association of each of the anxiety disorders with arthritis. Across the four anxiety disorders, the pooled OR estimates were all significantly greater than one, and all fell in the range 1.8–2.3.

Table 3.

Prevalence (%) of anxiety disorders among persons with versus without arthritisa

| Country | No arthritis | Arthritis | OR (95% CI) adjusted | No arthritis | Arthritis | OR (95% CI) adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized anxiety |

Agoraphobia or panic disorder |

|||||

| Colombia | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 (0.4–3.8) | 2.1 | 3.2 | 1.3 (0.5–3.5) |

| Mexico | 0.5 | 1.4 | 3.1 (1.0–9.3)* | 1.2 | 2.9 | 2.4 (1.2–4.8)* |

| USA | 3.4 | 5.9 | 2.3 (1.7–3.1)* | 3.1 | 5.0 | 2.4 (1.7–3.3)* |

| Japan | 1.5 | 2.5 | 1.9 (0.6–5.9) | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.7 (0.2–13.4) |

| Beijing, PRC | 1.0 | 2.3 | 1.9 (0.9–4.0) | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 (0.1–10.7) |

| Shanghai, PRC | 0.2 | 3.6 | 9.5 (1.6–55.9)* | 0.1 | 0.0 | N.E. |

| New Zealand | 2.8 | 3.9 | 2.1 (1.6–2.9)* | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.1 (1.5–3.0)* |

| Belgium | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.9 (0.3–12.2) | 1.3 | 2.2 | 3.5 (1.0–12.7) |

| France | 1.6 | 3.2 | 4.1 (1.9–9.0)* | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.8 (0.8–4.5) |

| Germany | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 (0.1–5.0) | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 (0.2–3.8) |

| Italy | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.7 (0.5–6.2) | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.6 (0.7–3.7) |

| Netherlands | 1.0 | 1.3 | 2.0 (0.5–8.2) | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 (0.4–4.3) |

| Spain | 0.7 | 2.0 | 3.1 (1.2–7.9)* | 0.6 | 1.7 | 3.5 (1.9–6.7)* |

| Ukraine | 1.4 | 6.0 | 3.4 (2.0–5.8)* | 1.3 | 4.0 | 2.5 (1.3–4.7)* |

| Lebanon | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 (0.1–4.3) | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.2 (0.2–28.4) |

| Nigeria | 0.0 | 0.2 | N.E. | 0.1 | 1.1 | 7.0 (1.6–30.2)* |

| Israel | 2.4 | 4.5 | 1.8 (1.0–3.0)* | 0.7 | 2.9 | 3.6 (1.9–6.7)* |

| South Africa | 1.7 | 3.5 | 1.5 (0.7–3.2) | 5.2 | 8.5 | 1.6 (1.1–2.3)* |

| Pooled OR | – | – | 2.3 (1.9–2.6)* | – | – | 2.2 (1.9–2.5)* |

| Social phobia |

PTSD |

|||||

| Colombia | 2.8 | 3.7 | 1.7 (0.7–4.0) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 (0.2–4.2) |

| Mexico | 1.7 | 5.3 | 3.8 (1.9–7.3)* | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 (0.1–3.3) |

| USA | 6.6 | 7.5 | 1.8 (1.4–2.2)* | 2.9 | 5.2 | 2.6 (2.0–3.4)* |

| Japan | 0.6 | 0.0 | N.E. | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 (0.0–4.1) |

| Beijing, PRC | 0.4 | 0.0 | N.E. | 0.3 | 0.0 | N.E. |

| Shanghai, PRC | 0.0 | 0.0 | N.E. | 0.0 | 0.8 | N.E. |

| New Zealand | 5.1 | 4.7 | 1.5 (1.1–2.0)* | 2.8 | 4.0 | 1.9 (1.3–2.8)* |

| Belgium | 0.8 | 2.2 | 7.0 (1.3–37.1)* | 0.5 | 1.2 | 2.2 (0.7–6.6) |

| France | 2.8 | 2.2 | 1.1 (0.5–2.7) | 2.0 | 3.1 | 2.1 (1.1–4.1)* |

| Germany | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0.3 (0.1–1.6) | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.4 (0.5–3.6) |

| Italy | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 (0.4–3.2) | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.4 (0.5–3.9) |

| Netherlands | 1.2 | 2.2 | 3.4 (0.8–15.3) | 2.4 | 3.1 | 0.8 (0.2–3.2) |

| Spain | 0.6 | 1.0 | 4.5 (1.4–14.5)* | 0.4 | 0.9 | 2.3 (0.8–6.8) |

| Ukraine | 1.8 | 3.2 | 3.7 (1.5–9.4)* | 2.3 | 4.5 | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) |

| Lebanon | 0.6 | 0.0 | N.E. | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 (0.1–2.2) |

| Nigeria | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.8 (0.0–15.3) | 0.0 | 0.0 | N.E. |

| Israel | – | – | N.E. | 0.5 | 1.1 | 2.1 (0.8–5.5) |

| South Africa | 1.7 | 3.8 | 2.7 (1.2–5.8)* | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 (0.2–2.5) |

| Pooled OR | – | – | 1.8 (1.6–2.1)* | – | – | 1.9 (1.6–2.3)* |

OR, Odds ratio (adjusted for age and sex); CI, confidence interval; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; N.E., non-estimable; –, information not available.

Country not included if less than 25 respondents have the physical condition.

p ≤ 0.05.

The association of any anxiety disorder with arthritis (Fig. 2) showed a pattern similar to that observed for any mood disorder (Fig. 1). The pooled estimate of the ORs was 1.9. Of the 18 survey-specific estimates, the 95% CIs for all but three surveys included the pooled estimate of the ORs. As was the case for mood disorder, the estimates that diverged from the pooled estimate tended to have low precision. These results indicate that the strength of the association of anxiety disorders, as a class, with arthritis is comparable to that observed for mood disorders.

Fig. 2.

Odds ratios (age- and sex-adjusted) for anxiety disorder for persons with versus without arthritis. For abbreviations see Fig. 1 legend.

Alcohol abuse/dependence

In 10 of the 18 countries, less than 1% of those with arthritis had co-morbid alcohol abuse or dependence. In the remaining surveys, the prevalence of alcohol abuse or dependence ranged from 1.9% (Belgium) to 5.2% (Colombia). ORs adjusted for age and sex for the association of alcohol abuse or dependence with arthritis were estimated for 14 surveys, of which three were significantly greater than one. These OR estimates were not found to be heterogeneous across surveys (p = 0.24). The pooled estimate of the ORs for the association of alcohol abuse or dependence and arthritis was 1.5, with a 95% CI that did not include one. These results suggest that alcohol abuse may occur with somewhat greater frequency among persons with arthritis. However, in many countries the prevalence of alcohol abuse or dependence among persons with arthritis was fairly low.

The results of drug abuse/dependence and arthritis are not reported here because the number of cases was too small to generate reliable conclusions.

Discussion

This report provides the first large-scale, population-based assessment of the frequency and association of both mood and anxiety disorders with arthritis. As the participating surveys included countries that differed markedly in culture, language and level of socioeconomic development, the consistency in findings across countries is remarkable. The key finding of the study that different mood and anxiety disorders have similar associations with arthritis has implications for clinical practice. It suggests that clinicians need to be aware of a spectrum of mood and anxiety disorders occurring with increased frequency among persons with arthritis. This suggests that clinicians should evaluate depression and anxiety status of patients with arthritis, particularly among those with significant activity limitations, in light of evidence from a large randomized controlled trial that treating depression among persons with arthritis who are depressed improves functional outcomes (Lin et al. 2003). These results point to the need for additional research, particularly randomized controlled trials evaluating the benefits of treating co-morbid depression and anxiety among person with arthritis, and prospective studies that clarify understanding of the extent to which depressive and anxiety disorders are risk factors and/or consequences of arthritis pain and associated activity limitations.

The observed associations have limited implications for understanding causal relationships. However, the fact that both mood and anxiety disorders show a similar level of association with arthritis suggests that any effects of arthritis on psychological functioning may influence anxiety states as well as mood. Similarly, if psychological disorder increases risks of arthritis, the role of anxiety disorder should be considered as well as mood disorder. Co-morbidity of depression and anxiety is common. It has been determined that non-co-morbid depressive and anxiety disorders are associated in equal degree with diverse physical conditions including arthritis. Co-morbid depressive-anxiety disorder was reported to be more strongly associated with arthritis than were single mental disorders (Scott et al. 2007).

The survey results for alcohol use disorders were limited by their relatively low frequency among persons with arthritis. Although the pooled estimate indicated that alcohol abuse or dependence tended to be more common among persons with arthritis than those without, the rates of alcohol abuse/dependence among persons with arthritis were low in most countries.

Of interest, the individual surveys seem to yield disparate results if examined individually. For example, for the estimated association between major depression and arthritis, half of the surveys indicated a significant association. The reason for this apparent discordance is not clear. It could be due to the small number of cases in some surveys, differences in the accuracy of self-report across different countries, or true differences. However, when the survey specific estimates were examined in the context of the pooled estimate, a more consistent and informative picture emerged. For both mood and anxiety disorders, the odds of having a mental disorder was about 2 to 1 for persons with versus without arthritis. Moreover, the pooled estimate of the ORs generally fell within the 95% CIs of the estimates from the individual surveys. This suggests that future research on the association of mood and anxiety disorders with arthritis should consider larger survey samples or multiple surveys. In addition, it may be more useful to examine different mood and anxiety disorders and investigate their relationship as a broad category with arthritis rather than looking at specific disorders that occur with lower frequency, particularly in sample surveys of limited size. Tests of significance for the association of specific mental disorders with arthritis from a single survey may be unreliable for lower prevalence mental disorders.

Limitations

The most notable limitation of this research is the ascertainment and recall bias of arthritis based on self-report. As the WMH Surveys were multi-faceted and conducted in large populations worldwide, it was not feasible to examine medical records or to conduct a standardized medical assessment to determine whether arthritis was present or absent. Limited evidence of the agreement of self-report and medical record data was from prior research among special populations in developed countries. A study of the reporting of chronic conditions in the National Health Interview Survey among persons with recent medical contact reported moderate validity (k = 0.406) (National Center for Health Statistics, 1994). Lin et al. (2003) confirmed 91.4% of self-report among older adults reporting diagnosis or treatment for arthritis from a health-care provider in the past 3 years. Moreover, the prevalence pattern of arthritis in the WMH Surveys seems to be consistent with the expected epidemiological patterns (higher prevalence among females and increasing prevalence with age), adding to the validity of the data.

The large variations in arthritis prevalence rates found in our study are difficult to account for by differences in the age and educational level of the samples. Our research was not able to explain these differences.

As pooled estimates were based on the inverse variance weighting method, more weight is given to estimates from the larger samples (e.g. New Zealand, the USA) that have smaller variances.

It is possible that the association of mood and anxiety disorders with arthritis can be explained by non-specific factors associated with the report of chronic illness in general, rather than an association specific to arthritis. Mood and anxiety disorders are associated with many different chronic physical conditions, especially chronic pain conditions. In prior research, it was found that 48% of patients with persistent pain reported back pain and 42% reported joint pain (Gureje et al. 1998). Further research is needed to determine whether there are factors that contribute to the association of arthritis and psychological illness shared with other chronic conditions (Berkanovic & Hurwicz, 1990; John et al. 2003; Foley et al. 2004).

Our research is not able to provide information on the association of mental disorders with specific types of arthritis (e.g. osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis) or with the severity of arthritis. Although previous research has not established differences in association between mood disorders and specific kinds of arthritis, differences have been reported by arthritis severity, especially for mobility (i.e. people who are depressed have greater problems with mobility) (Dunlop et al. 2004; Lowe et al. 2004).

Notable strengths of the WMH Surveys include the use of standardized and well-validated methods to diagnose mental disorders in a community survey, and the size and diversity of the surveys. It was possible to develop population-based estimates for an unprecedented range of mental disorders among community-dwelling adults reporting arthritis.

Conclusions

The WMH Surveys showed that mood and anxiety disorders occurred among persons with arthritis at higher rates than among persons of comparable age and sex without arthritis. This association was observed across different countries with diverse cultures, languages and levels of socio-economic development. The associations of specific mood and anxiety disorders with arthritis appeared similar. Abuse of alcohol was more common among persons with arthritis, but this relationship was observed in only a minority of the surveys. These results should be taken into consideration in clinical practice in light of the burden caused by the co-morbidity of mental disorders with arthritis.

Acknowledgements

The surveys discussed in this article were carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864 and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. The Chinese World Mental Health Survey Initiative is supported by the Pfizer Foundation. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection, with supplemental support from the Saldarriaga Concha Foundation. The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CIBER CB06/02/0046, RETICS RD06/0011 REM-TAP), and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The Israel National Health Survey is funded by the Ministry of Health with support from the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research and the National Insurance Institute of Israel. The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. The Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (LEBANON) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from Janssen Cilag, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Novartis. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544-H), with supplemental support from the PanAmerican Health Organization (PAHO). Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) is supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council, and the Health Research Council. The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) is supported by the WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria), and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. The South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH) is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. The Ukraine Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption (CMDPSD) study is funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (RO1-MH61905). The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Ang DC, Choi H, Kroenke K, Wolfe F. Comorbid depression is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 2005;32:1013–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association. 4th edn. Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Berkanovic E, Hurwicz ML. Rheumatoid arthritis and comorbidity. Journal of Rheumatology. 1990;17:888–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird SM, Cox D, Farewell VT, Goldstein H, Holt T, Smith PC. Performance indicators: good, bad, and ugly. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A. 2005;168:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona L, Ballina J, Gabriel R, Laffon A EPISER Study Group. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the general population of Spain: results from a national survey. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2001;60:1040–1045. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.11.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Prevalence of arthritis – United States, 1997. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2001;50:334–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham LS, Kelsey JL. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74:574–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.6.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bonnewyn A, Bruffaerts R, Brugha T, Graaf R, Alonso J. Comorbid painful physical symptoms and depression: prevalence, work loss, and help seeking. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;92:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens C, Jackson J, Tomenson B, Hay E, Creed F. Association of depression and rheumatoid arthritis. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:209–215. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop DD, Lyons JS, Manheim LM, Song J, Chang RW. Arthritis and heart disease as risk factors for major depression: the role of functional limitation. Medical Care. 2004;42:502–511. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000127997.51128.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators. Sampling and methods of the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 2004;420:8–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson DT, Naimark A, Anderson J, Kazis L, Castelli W, Meenan RF. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1987;30:914–918. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, Walsh J. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;56:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Anthony JM, Zhang Y, Wilson PW, Kelly-Yayes M, Wolf PA, Kreger BE, Kannel WB. The effects of specific medical condition on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:351–358. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O, Von Korff M, Kola L, Demyttenaere K, He YL, Posada-Villa J, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Levinson D, Girolamo G, Iwata N, Karam A, Guimaraes Borges GL, Graaf R, Browne MO, Stein DJ, Haro JM, Bromet EJ, Kessler RC, Alonso J. The relation between multiple pains and mental disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Pain. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.05.005. Published online: 12 June 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Grater R. Persistent pain and wellbeing: a World Health Organization study in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:147–151. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, de Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Lepine JP, Mazzi F, Reneses B, Vilagut G, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2006;15:167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmick CG, Lawrence RC, Pollard RA, Lloyd E, Heyse SP. Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions: who is affected now, who will be affected later? Arthritis Care and Research. 1995;8:203–211. doi: 10.1002/art.1790080403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John R, Kerby DS, Hennessy CH. Patterns and impact of comorbidity and multimorbidity among community-resident American Indian elders. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:649–660. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell B-P, Walters EE, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ormel J, Demler O, Stang PE. Comorbid mental disorders account for the role impairment of commonly occurring chronic physical disorders: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Occupational Environment Medicine. 2003;45:1257–1266. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000100000.70011.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khongsaengdao B, Louthrenoo W, Srisurapanont M. Depression in Thai patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research. 2000;83:743–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegsman DMW, Penninx BWJH, van Eijk JThM, Boeke AJP, Deeg DJH. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients’ self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1996;49:1407–1417. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, Heyse SP, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Liang MH, Pillemer SR, Steen VD, Wolfe F. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1998;41:778–799. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M, Tang L, Williams JW, Kroenke K, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, Hegel M, Arean P, Hoffing M, Penna RD, Langston C, Unutzer J. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:2428–2434. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe B, Willand L, Eich W, Zipfel S, Ho AD, Herzog W, Fiehn C. Psychiatric comorbidity and work disability in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannoni A, Briganti MP, Di Bari M, Ferrucci L, Costanzo S, Serni U, Masotti G, Marchoinni N. Epidemiological profile of symptomatic osteoarthritis in older adults: a population based study in Dicomano, Italy. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2003;62:576–578. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.6.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen WM, Dodge HJ, Duff IF, Kato H. Estimates of the prevalence of rheumatic diseases in the population of Tecumseh, Michigan, 1959–60. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1967;20:351–369. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mili F, Helmick CG, Zack MM. Prevalence of arthritis: analysis of data from the US Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1996–1999. Journal of Rheumatology. 2002;29:1981–1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Evaluation of National Health Interview Survey diagnostic reporting. Vital and Health Statistics Series 2. 1994;120:1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Reed JI, Cirillo PA, Walker AM. Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip, and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organization. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1995;38:1134–1141. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Datto CJ, Kallan MJ, Katz IR, Edell WS, TenHave T. Association between medical comorbidity and treatment outcomes in late-life depression. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:823–828. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRC. Morbidity Rate of Chronic Diseases. Accessed 1 February 2006. 2003 Ministry of Health, People’s Republic of China ( www.moh.gov.cn/open/statistics/digest05/s61.htm)

- Reginster JY. The prevalence and burden of arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41 Suppl. 1:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Bruffaerts R, Tsang A, Ormel J, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Benjet C, Bromet E, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Gasquet I, Gureje O, Haro JM, He Y, Kessler RC, Levinson D, Mneimneh ZN, Oakley Browne MA, Posada-Villa J, Stein DJ, Takeshima T, Von Korff M. Depression-anxiety relationships with chronic physical conditions: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;103:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stang PE, Brandenburg NA, Lane MC, Merikangas KR, Von Knorff MR, Kessler RC. Mental and physical comorbid conditions and days in role among persons with arthritis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:152–158. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195821.25811.b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUDAAN. SUDAAN software version 8.0.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vali FM, Walkup J. Combined medical and psychological symptoms: impact on disability and health care utilization of patients with arthritis. Medical Care. 1998;36:1073–1084. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Saase JL, van Romunde LK, Cats A, Vandenbroucke JP, Valkenburg HA. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: Zoetermeer survey. Comparison of radiological osteoarthritis in a Dutch population with that in 10 other populations. Annals of Rheumatic Diseases. 1989;48:271–280. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.4.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yelin EH. Musculoskeletal conditions and employment. Arthritis Care and Research. 1995;8:311–317. doi: 10.1002/art.1790080417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelin EH, Callahan LF. The economic cost and social and psychological impact of musculoskeletal conditions. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1995;38:1351–1362. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Xu L, Nevitt MC, Aliabadi P, Yu W, Qin MW, Lui LY, Felson DT. Comparison of the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis between the elderly Chinese population in Beijing and whites in the United States. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2001;44:2065–2071. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2065::AID-ART356>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]