Abstract

Docetaxel is a potent anti-cancer drug. However, there continues to be a need for alternative docetaxel delivery systems to improve its efficacy. We reported the engineering of a novel spherical nanoparticle formulation (~270 nm) from lecithin-in-water emulsions. Docetaxel can be incorporated into the nanoparticles, and the resultant docetaxel-nanoparticles were stable when stored as an aqueous suspension. The release of the docetaxel from the nanoparticles was likely caused by a combination of diffusion and Case II transport. The docetaxel-in-nanoparticles were more effective in killing tumor cells in culture than free docetaxel. Moreover, the docetaxel-nanoparticles did not cause any significant red blood cell lysis or platelet aggregation in vitro, nor did they induce detectable acute liver damage when injected intravenously into mice. Finally, compared to free docetaxel, the intravenously injected docetaxel-nanoparticles increased the accumulation of the docetaxel in a model tumor in mice by 4.5-fold. These lecithin-based nanoparticles have the potential to be a novel biocompatible and efficacious delivery system for docetaxel.

Keywords: nanoparticles, emulsions, cell uptake, cytotoxicity, biocompatibility

1. Introduction

Recently, nanoparticles have gained much attention as a delivery system for anticancer drugs, primarily due to their unique properties that can potentially improve the efficacy of these drugs (Allen and Cullis, 2004). For example, nanoparticles may be used to enhance the solubility of poorly-water soluble anti-cancer drugs and to modify their pharmacokinetics (Gabizon et al., 2003). Nanoparticles may also be engineered to reduce the uptake of the drugs by the reticuloendothelial system and / or to target the drugs to specific tumor cells (Allen, 2002; Emerich and Thanos, 2006). Additionally, there were data showing that nano-sized drug carriers can overcome the multi-drug resistance in many cancer cells (Jabr-Milane et al., 2008).

Docetaxel is a semi-synthetic anticancer agent in the taxane class. It is potent against many solid tumors such as breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer (Clarke and Rivory, 1999). In spite of its high efficiency, side effects limit the clinical use of the docetaxel. The current formulation of docetaxel contains Tween 80 and ethanol (50:50, v/v) as the solvent, and adverse reactions due to either the drug itself or the solvent system have been reported in patients (e.g., hypersensitivity, fluid retention) (ten Tije et al., 2003). Therefore, many alternative docetaxel formulations such as liposomes (Immordino et al., 2003), polymeric nanoparticles (Hwang et al., 2008), micelles (Liu et al., 2008), and solid lipid nanoparticles (Xu et al., 2009) have been investigated.

Previously, our laboratory reported the preparation of a nanoparticle formulation from lecithin-in-water emulsions (Cui et al., 2006). Lecithins are components of cell membranes and are regularly consumed as part of a normal diet (Jimenez et al., 1990; Wade and Weller, 1994). They are used extensively in pharmaceutical applications as emulsifying, dispersing, and stabilizing agents and are included in intramuscular and intravenous injectables and other parenteral nutrition formulations (Lixin et al., 2006; Williams et al., 1984). In the present study, we investigated the feasibility of using the nanoparticles as a carrier for docetaxel. Our data showed that the docetaxel can be incorporated in the nanoparticles, and the docetaxel in the nanoparticles was more effective in killing tumors cells in culture than free docetaxel. Our data also showed that the docetaxel-loaded nanoparticles were biocompatible and tended to increase the accumulation of the docetaxel in tumors pre-established in mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Docetaxel was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). Lecithin (soy, refined) was from MP Biomedicals, LLC (Santa Ana, CA). The 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanoamine-N-[methoxy (polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG-2000) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(carboxyfluorescien) (FITC-DOPE) were from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc (Alabaster, AL). Sepharose ® 4B, MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) kit, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and epinephrine were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Cellulose dialysis tubes (MWC 50,000) were from Spectrum Chemicals & Laboratory Products (New Brunswick, NJ). Citrated whole mouse blood was from Pel-Freez Biologicals (Rogers, AR). Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) kit was from Teco Diagnostic (Anaheim, CA).

2.2. Mice and cell lines

Female BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice, 6-7 weeks of age, were from Simonsen Laboratories, Inc. (Gilroy, CA). The TC-1 cells (a mouse lung cancer line) and PC-3 cells (a human prostate cancer line) were from ATCC and grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin (Invitrogen), and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin (Invitrogen).

2.3. Preparation of the nanoparticles

Nanoparticles were prepared from emulsions (Cui et al., 2006). Briefly, 4 mg of lecithin was weighed into a 7-mL glass scintillation vial. One mL of de-ionized, filtered (0.2 μm) warm water was added into the vial, followed by heating on a hot plate to 50-55°C with stirring until a milky dispersion was formed. Tween 20 was added in a step-wise manner to a final concentration of 2% (v/v). The milky dispersion was stirred until a smooth, less opaque, but not clear system was formed, which was then allowed to cool down to room temperature while stirring. The particle size was determined by photon correlation spectroscopy (PCS) using a Coulter N4 Plus Submicron Particle Sizer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA).

To prepare docetaxel (DTX)-loaded nanoparticles (DTX-NPs), various amount of docetaxel (50 to 250 μg) in chloroform was added into a glass vial containing 4 mg of lecithin, and the chloroform was evaporated. The remaining steps were similar to the preparation of the blank nanoparticles. Similarly, to incorporate DSPE-PEG-2000 into the nanoparticles, the DSPE-PEG-2000 (5% of the lecithin (m/m), or 10% where mentioned) was added into a glass vial containing lecithin prior to the nanoparticle preparation. Unloaded docetaxel was separated from the nanoparticles using gel permeation chromatography (GPC, Sepharose 4B, 6 × 150 mm). The eluted fractions were analyzed for docetaxel by measuring the absorption at 230 nm.

Nanoparticles were freeze-dried using a FreeZone 6 Liter Freeze Dry System (Labconco, Kansas City, MI). Dextrose (5%, w/v) was used as the lyoprotectant.

2.4. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The size and morphology of the nanoparticles were examined using a transmission electron microscope (TEM, Philips CM12 TEM/STEM) in the Oregon State University Electron Microscope Facility as previously described (Cui and Mumper, 2002).

2.5. In vitro release of docetaxel from the nanoparticles

Lyophilized docetaxel-loaded, PEG-2000-containing nanoparticles (DTX-PEG-NPs, 10% of DSPE-PEG-2000, m/m) were suspended in 1 mL of de-ionized water (final docetaxel concentration, 100 μg/mL) and placed into a 1 mL cellulose ester dialysis tube (MCW 50,000). The tube was incubated in a 13 mL of release medium (0.5% of SDS in PBS, 10 mM, pH 7.4) at 37°C under horizontal shaking. At predetermined time points, the dialysis tube was taken out and was re-placed into a new 13 mL fresh medium. In order to detect docetaxel in the release medium, the docetaxel molecules have to be released from the nanoparticles and then diffuse across the cellulose ester dialysis membrane. To make sure that the diffusion of the docetaxel molecules across the membrane was not the rate-limiting step, docetaxel was dissolved in Tween 80 (20 mg/mL) and diluted with 13% ethanol to the concentration of 5 mg/mL. It was then diluted with de-ionized water to a final docetaxel concentration of 100 μg/mL and placed into a dialysis tube as described above. The amount of docetaxel released was determined by an HPLC method with the following conditions: Zorbax Eclipse Plus® C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, pore size 5 μm, Aligent), the mobile phase: CH3CN:H2O (1:1, v/v), flow rate: 1.0 mL/min, and measured wavelength: 230 nm (Xu et al., 2009).

2.6. The uptake of the nanoparticles by tumor cells in culture

Nanoparticles were prepared without docetaxel to avoid its cytotoxicity. FITC-DOPE was incorporated into the nanoparticles for fluorescent detection. TC-1 cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in a 24-well plate and incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. The cells were then incubated with 500 μL of FITC-labeled nanoparticles (FITC-NPs) or FITC-labeled, PEG-2000-containing nanoparticles (FITC-PEG-NPs) (1.5 times dilution) at 4°C or 37°C for 2 h or longer. At 4°C, the internalization of the nanoparticles was inhibited, and thus, a comparison of the data at 4°C and 37°C was informative of the internationalization of the particles. After the incubation, the cells were washed 3 times with cold PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) and lysed with a lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100). The fluorescence intensity was measured using a BioTek Synergy HT Multi-Detection Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc. Winooski, VT).

2.7. In vitro cytotoxicity assays

Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (3,000/well) and incubated with the DTX-PEG-NPs or free docetaxel dissolved in DMSO for 24 or 48 h. The final concentration of the docetaxel in the cell culture medium was adjusted to 100 nM. At this concentration, both the nanoparticles without docetaxel and the DMSO did not cause any significant cell death. The number of surviving cells was determined using the MTT assay (Le et al., 2008).

2.8. Biocompatibility of the docetaxel-nanoparticles

The red blood cell (RBC) lysis assay was carried out as described with slight modifications (Koziara et al., 2005). Citrated whole mouse blood was mixed at a 1:1 (v/v) ratio with water as a positive control or with normal saline as a negative control. Freshly prepared DTX-PEG-NPs (50 μg/mL docetaxel) were diluted 1, 10, 100, or 1,000-fold with 0.9% NaCl prior to mixing with the blood. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a shaker followed by centrifugation at 600 × g for 5 min to remove the undamaged erythrocytes. Supernatant was collected and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Oxyhemoglobin was measured at 540 nm. To evaluate the effect of the incubation time on the RBC lysis in the presence of the nanoparticles, DTX-PEG-NPs (5 μg/mL docetaxel) were incubated with the blood for up to 6 h.

The platelet aggregation assay was also completed as previously described (Oyewumi et al., 2004). Briefly, citrated whole mouse blood was centrifuged to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-poor plasma (PPP) (Yang et al., 1999). Freshly prepared DTX-PEG-NPs (50 μg/mL docetaxel) were diluted and incubated for 10 min with the PRP containing 106 platelets in a final volume of 1 mL at 37°C in an incubator shaker. Platelet aggregation was measured at 500 nm. The absorptions of the PRP, PPP, and the DTX-PEG-NPs alone were also measured as controls. Epinephrine (10 mM) was used as a positive control.

2.9. In vivo plasma ALT determination

Healthy BALB/c mice were injected intravenously via the tail vein with normal saline or the DTX-PEG-NPs (with 10 μg of docetaxel). Polyinosinic-cytodylic acid (pI:C) (50 μg/mouse), which was previously shown to increase plasma ALT activity, was used as a positive control. After 24 h, the mice were euthanized. Plasma ALT activity was measured using the ALT kit. A high plasma ALT level is an indication of liver damage. Generally, an ALT increase of 3-5-fold higher than that in the untreated control mice is considered toxic.

2.10. The accumulation of docetaxel in tumors in mice

TC-1 cells were subcutaneously implanted in the flank of C57BL/6 mice (n = 4-5, 5 × 105 cells/mouse). Seventeen days after the implantation, the mice were injected intravenously with free docetaxel or DTX-PEG-NPs (PEG-2000, 10% m/m, docetaxel, 1 mg per kg of body weight in 200 μL). Tumor samples were collected 4 h later and homogenized. Docetaxel was extracted from the tumor samples with methanol and quantified using HPLC as described above (Xu et al., 2009). The data were normalized to the sample weight.

2.11. Data and statistical analyses

The in vitro release of the docetaxel from the PEG-2000-containing nanoparticles (DTX-PEG-NPs) was modeled using the equation M = k tn, where M is the % of total docetaxel released and t is time (Ritger and Peppas, 1987). The parameter k is the kinetic constant, incorporating the structural and geometric characteristics of the release system. From the value of exponential component (n), the mechanism of the in vitro release was determined. The computer software program MATLAB® (Natick, MA) was used to fit the data. Statistical analyses were completed using ANOVA followed by the Fischer’s protected least significant difference procedure. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 (two-tail) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation of nanoparticles from lecithin-in-water emulsions

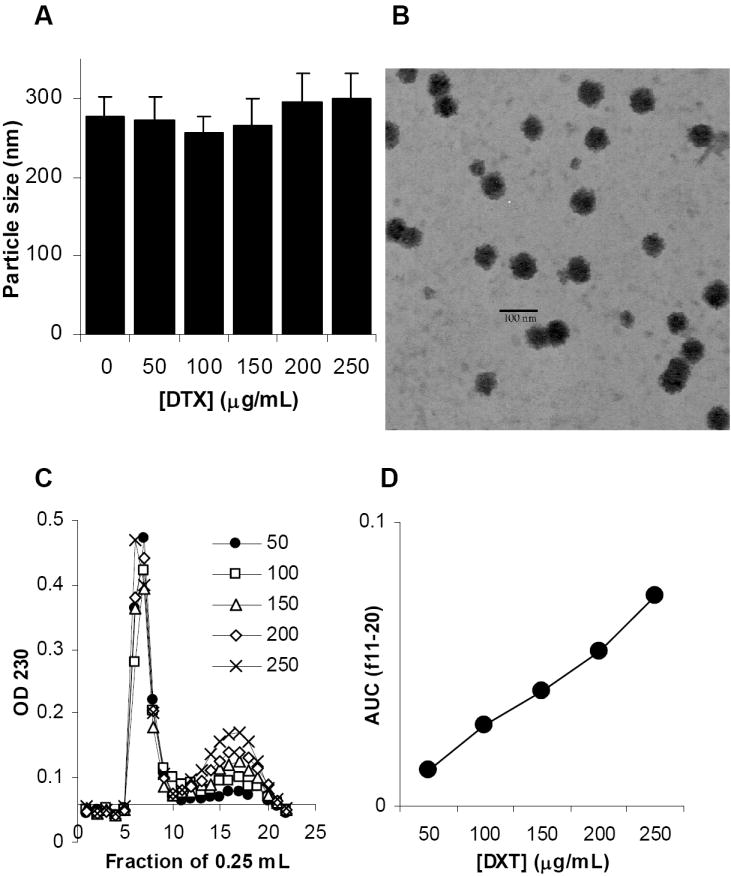

Lecithin is an integral part of the cell membrane. It is a complex mixture of phosphatides consisting of phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylinositol and other substances such as triglycerides and fatty acids. It is GRAS (generally regarded as safe) listed and accepted in the FDA Inactive Ingredients Guide for parenterals (e.g., 0.3-2.3% for intramuscular injection) (Wade and Weller, 1994). Tween 20 is a polyoxyethylene derivative of sorbitan monolaurate. It is also GRAS listed and included in the FDA Inactive Ingredients Guide for parenterals (Wade and Weller, 1994). Thus, the nanoparticles were prepared from emulsions using lecithin as the oil phase and Tween 20 as the surfactant. With 4 mg/mL of lecithin and 2% Tween 20, nanoparticles of around 270 nm were generated (Fig.1A). Docetaxel can be incorporated into the nanoparticles, and it seemed that the incorporation of the docetaxel did not significantly affect the size of the resultant nanoparticles (Fig. 1A) (p = 0.12, ANOVA). The nanoparticles were spherical (Fig. 1B). As expected, the average size of the nanoparticles derived from the micrograph was apparently smaller than that determined using the particle sizer (photon correlation spectroscopy, PCS). The particle size from the PCS measurement was the size of the particles plus an aqueous layer that surrounds the particles and moves together with the particles. Data in Fig. 1C showed that free docetaxel can be separated from the nanoparticles using a Sepharose 4B column. When 50 μg/mL of docetaxel was added during the nanoparticle preparation, close to 100% of the docetaxel was incorporated into the nanoparticles (Fig. 1D). When more docetaxel was added into the preparation, an increasing amount of it was found in the micelle fractions (Fig. 1D, fractions 11-20). Therefore, the nanoparticles prepared with 50 μg/mL of docetaxel were used for further study without purification.

Fig. 1. Preparation of DTX-NPs.

A. The size of nanoparticles prepared with different concentrations of docetaxel (mean ± S.D., n = 3).

B. The micrograph of the nanoparticles prepared without docetaxel (NPs).

C. The gel permeation chromatograph of DTX-NPs prepared with different concentrations of docetaxel. DTX-NPs suspension was applied to Sepharose 4B column. The absorbance of the elution fractions (0.25 mL) at 230 nm was measured.

D. Area under the curve (AUC) of the GPC fractions 11-20 in C calculated by trapezoidal method.

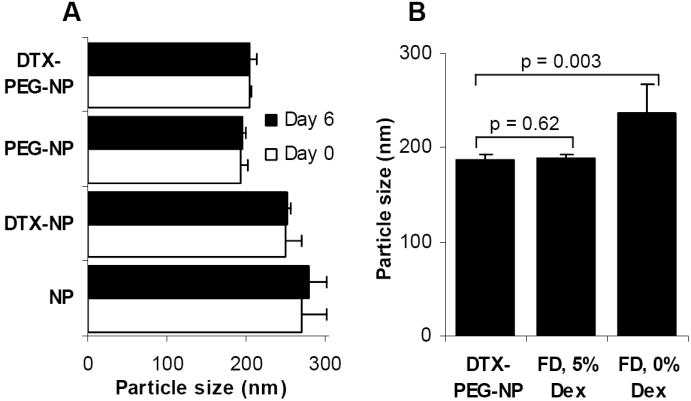

Data from a short-term stability study showed that the nanoparticles, with or without PEG-2000, were stable when stored at room temperature in an aqueous suspension (Fig. 2A). The polyoxyethylene chains of the Tween 20 on the surface of the nanoparticles may have prevented the nanoparticles from aggregating. Similarly, no aggregation was observed when the nanoparticles were co-incubated in a simulated biological medium (10% fetal bovine albumin in PBS, 10 mM, pH 7.4) (data not shown), suggesting that it is very unlikely that the nanoparticles will aggregate after intravenous injection. Interestingly, the PEG-2000-containing nanoparticles, with or without docetaxel, were smaller than their corresponding PEG-2000-free nanoparticles (Fig. 2A). We speculate that this may be due to the significant change in the nanoparticle composition when the DSPE-PEG-2000 was included into the nanoparticles. The nanoparticles were also successfully lyophilized using dextrose (5%) as the lyoprotectant (Fig. 2B). If needed, the final optimized docetaxel-nanoparticle formulation may be stored long-term in a lyophilized form.

Fig. 2. The nanoparticles were stable and lyophilizable.

A. Docetaxel nanoparticles (DTX-NP) with or without PEG-2000 were freshly prepared and stored at room temperature for 6 days.

B. The size of the lyophilized DTX-PEG-NPs was comparable to that of the freshly prepared DTX-PEG-NPs (FD, freeze-dried; Dex, dextrose). The values reported were mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

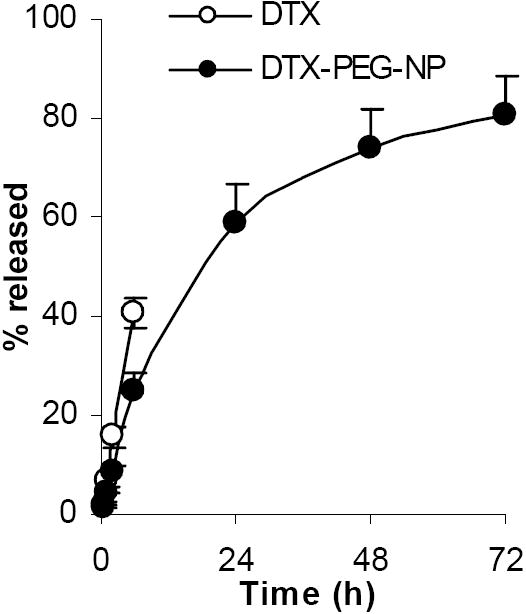

3.2. In vitro release of docetaxel from the nanoparticles

The release of the docetaxel from the nanoparticles was slow (Fig. 3). It took 3 days for 80% of the docetaxel to be released. The diffusion of the free docetaxel out of the dialysis tube was much faster (Fig. 3), demonstrating that the diffusion of the docetaxel across the semi-permeable dialysis membrane was not rate-limiting. When the first 60% of the release data of the DTX-PEG-NPs were fitted into the equation of M = k tn, a n-value of 0.72 ± 0.2 (R2 = 0.9908) was obtained. Thus, it is likely that both the diffusion of the docetaxel out of the nanoparticles and the process of the erosion of the nanoparticles have influenced the docetaxel release (Ritger and Peppas, 1987).

Fig. 3. The release of the docetaxel from the DTX-PEG-NPs.

The values reported were mean ± S.D. (n = 4).

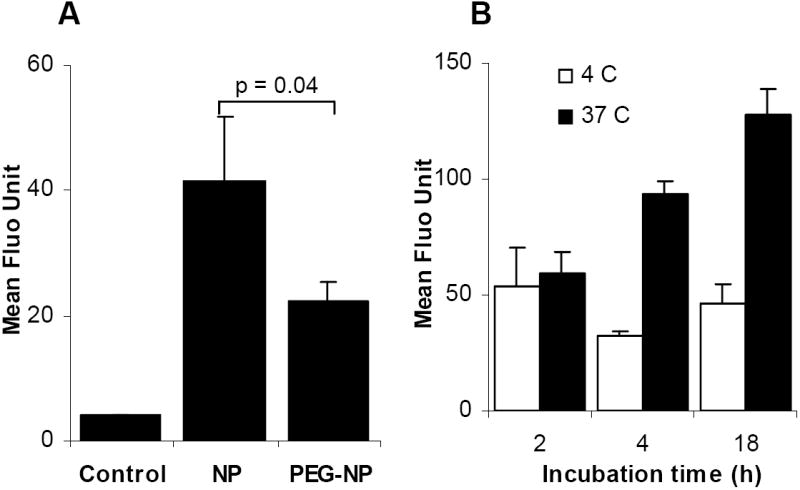

3.3. The uptake of the nanoparticles by tumor cells in culture

The uptake of the nanoparticles by tumor cells in vitro was studied using a model mouse lung cancer cell line, the TC-1 cells. The nanoparticles were labeled with FITC for fluorescent detection. As expected, after a 2 h incubation at 37°C, the uptake of the PEG-2000-containing nanoparticles (PEG-NPs) by the TC-1 cells was less than the uptake of the PEG-2000-free nanoparticles (NPs) (Fig. 4A). However, the uptake of the PEG-NPs by the TC-1 cells was significantly increased by prolonging the incubation time to 18 h (Fig. 4B). Clearly, the polyethylene glycol groups of the Tween 20 and the DSPE-PEG-2000 do not have the same activity. When the TC-1 cells and the nanoparticles were incubated together at 4°C, the amount of nanoparticles associated with the TC-1 cells did not significantly increase even after a prolonged incubation period (p = 0.132, ANOVA), indicating that at 37°C, the nanoparticles were internalized by the cells, not just simply bound on the cell surface.

Fig. 4. The uptake of the nanoparticles by TC-1 cells in culture.

A. The uptake of NPs and PEG-NPs by TC-1 cells at 37°C. Control was from cells incubated with culture medium alone. Fluorescence intensity was determined after 2 h of incubation.

B. The effect of the incubation time on the uptake of the PEG-NPs by the TC-1 cells. Cells were incubated at 4°C or 37°C for up to 18 h. The three values at 4°C (white bars) were not different from one another (p = 0.13, ANOVA), whereas the three values at 37°C were different from one another (p = 0.0003, ANOVA). Data reported were mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

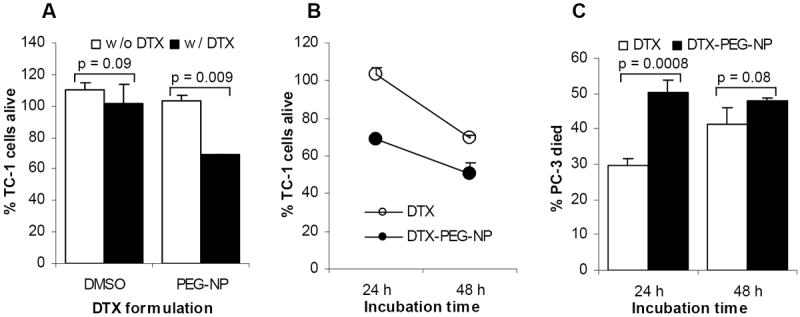

3.4. In vitro cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of the docetaxel-loaded, PEG-2000-containing nanoparticles (DTX-PEG-NPs) was evaluated using the TC-1 cells and PC-3 cells. After 24 h of incubation, close to 100% of the TC-1 cells incubated with free docetaxel in DMSO were still alive, while only about 60% of the TC-1 cells incubated with the DTX-PEG-NPs were alive (Fig. 5A). The cell death generated by the DTX-PEG-NPs was very likely due to the docetaxel in the nanoparticles, rather than the nanoparticles themselves, because the same concentration of the docetaxel-free PEG-NPs failed to cause any significant cell death (Fig. 5A). Increasing the incubation time from 24 h to 48 h led to more cell death (Fig. 5B). Moreover, when the incubation time was extended to 48 h, death was also detected in the cells treated with the free docetaxel (Fig. 5B). A similar trend was observed when the PC-3 cells were used (Fig. 5C). Taken together, it appeared that the docetaxel in the nanoparticle form was more effective in killing the tumor cells than the free docetaxel. Our data in Fig. 4 showed that the DTX-PEG-NPs were taken up by the TC-1 cells, especially after a prolonged incubation period. Thus, the improved cytotoxicity from the DTX-PEG-NPs may be due to the nanoparticles’ ability to facilitate or increase the uptake of the docetaxel by the tumor cells.

Fig. 5. The docetaxel in the nanoparticles was more effective in killing tumor cells in culture.

A. In vitro cytotoxicity against TC-1 cells. DMSO alone and the DTX-free PEG-NPs were used as controls.

B. The effect of the incubation time on the cytotoxicity of the DTX-PEG-NPs and free DTX in TC-1 cells (24 h vs. 48 h, p = 0.01 for the free DTX; p = 0.005 for the DTX-PEG-NP).

C. In vitro cytotoxicity against PC-3 cells. Data reported were mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

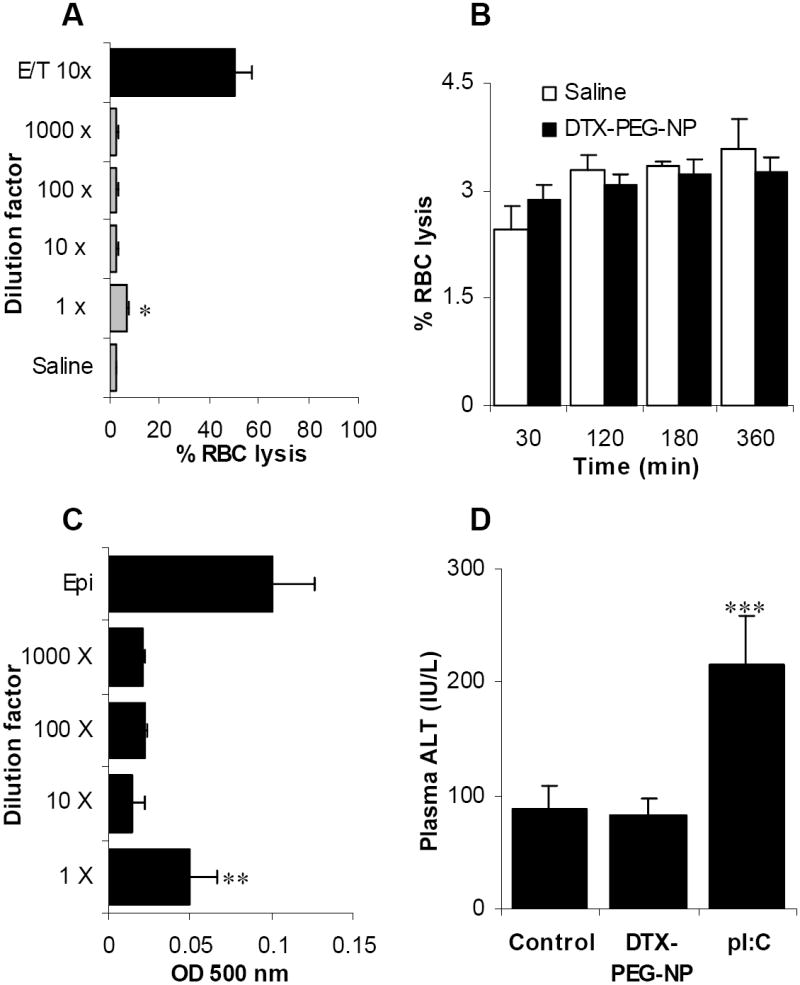

3.5. Biocompatibility of the docetaxel-nanoparticles

The docetaxel-nanoparticles were engineered for potential intravenous infusion. Thus, it is important to evaluate the biocompatibility of the nanoparticles because the nanoparticles may interact with the erythrocytes and cause anemia, jaundice, and other pathological conditions (De Jong and Borm, 2008; Zbinden et al., 1989). An evaluation of the compatibility of our docetaxel-nanoparticles (DTX-PEG-NPs) with blood was carried out in vitro. Incubation of the blood with an equal volume of the freshly prepared DTX-PEG-NPs (50 μg/mL docetaxel) resulted in a slight RBC lysis as compared to the osmotic cell lysis caused by water (Fig. 6A). At the dilution of 10, 100, or 1,000-fold, no significant RBC lysis was observed after 30 min of incubation (Fig. 6A). No significant RBC lysis was detectable even after the DTX-PEG-NPs (diluted 10-fold) were incubated with the blood for up to 6 h (Fig. 6B). In fact, there was not a significant difference in the RBC lysis values between the DTX-PEG-NPs and the normal saline at all time points examined (Fig. 6B). A platelet aggregation assay was also carried out in the presence of the DTX-PEG-NPs at various dilutions (starting from 50 μg/mL DTX). Data in Fig. 6C showed that the DTX-PEG-NPs at the dilutions of 10, 100, or 1,000-fold did not cause any significant platelet aggregation. Finally, no significant change in the plasma ALT level was observed 24 h after the DTX-PEG-NPs were injected intravenously into healthy mice (Fig. 6D), which is another indication of the potentially favorable biocompatibility profile of our docetaxol-loaded nanoparticles.

Fig. 6. The nanoparticles have a favorable biocompatibility profile.

A. DTX-PEG-NPs (diluted by 1, 10, 100, or 1,000-fold) were incubated with mouse blood for 30 min at 37°C. The % RBC lysis was determined. The docetaxel in ethanol and Tween 80 (E/T) preparation was included as a control. * The value of the 1 × group is different from that of the saline (p = 0.001) and that of the E/T (10 x) (p = 0.0003).

B. The effect of the incubation time on the RBC lysis in the presence of the DTX-PEG-NPs. The nanoparticles were diluted 10-fold.

C. The effect of the DTX-PEG-NPs on platelet aggregation. The DTX-PEG-NPs (50 μg/mL DTX) at various dilutions were incubated with mouse platelet-rich plasma, and the platelet aggregation was measured. Epinephrine (Epi) was used as a positive control. ** The value of the 1 × group is different from those of the other dilutions (p = 0.019, ANOVA).

D. The DTX-PEG-NPs did not cause any significant change in mouse plasma ALT level. The DTX-PEG-NPs (10 μg of DTX/mouse) was i.v. injected into mice and the plasmid ALT level was measured 24 h later. The pI:C (50 μg/mouse) was used as a positive control. The values from the Control (normal saline) and the DTX-PEG-NP were comparable (p = 0.84). *** The value of the pI:C was different from that of the other two (p = 0.014, ANOVA). All data reported were mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

3.6. The nanoparticles increased the accumulation of the docetaxel in tumors in mice

Finally, to preliminarily investigate whether the DTX-PEG-NPs can improve the accumulation of the docetaxel into tumors in vivo, the DTX-PEG-NPs were injected intravenously into C57BL/6 mice with pre-established TC-1 tumors. Four h after the injection, the amount of docetaxel recovered from the tumors in mice injected with the DTX-PEG-NPs was 3.4 ± 1.9 μg/g of tumor (mean ± S.D., n = 5), 4.5-fold higher than that in mice injected with the free docetaxel (0.76 ± 0.17 μg/g of tumor, n = 4). Another number in the free docetaxel group was identified as an outlier using the Grubb’s extreme studentized deviate (ESD) method. The data suggested the feasibility of using the nanoparticles to target the docetaxel into solid tumors.

4. Conclusions

We have engineered a new docetaxel formulation by incorporating the docetaxel into a lecithin-based nanoparticle carrier. The docetaxel in nanoparticles was more effective in killing tumor cells in culture. The nanoparticles were shown to be biocompatible and may be used to target the docetaxel into solid tumors to improve the resultant anti-tumor activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a National Cancer Institute grant CA135274 to Z.C. NY was supported in part by a fellowship from the Payap University, Thailand. BRS was supported in part by the OSU Yerex & Nellie Buck Yerex Graduate Fellowship and the OSU Sports Lottery Scholarship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen TM. Ligand-targeted therapeutics in anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:750–63. doi: 10.1038/nrc903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science. 2004;303:1818–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1095833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SJ, Rivory LP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of docetaxel. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;36:99–114. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199936020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Mumper RJ. Genetic immunization using nanoparticles engineered from microemulsion precursors. Pharm Res. 2002;19:939–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1016402019380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, et al. Lecithin-based cationic nanoparticles as a potential DNA delivery system. Int J Pharm. 2006;313:206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong WH, Borm PJ. Drug delivery and nanoparticles:applications and hazards. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3:133–49. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerich DF, Thanos CG. The pinpoint promise of nanoparticle-based drug delivery and molecular diagnosis. Biomol Eng. 2006;23:171–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabizon A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin: review of animal and human studies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:419–36. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HY, et al. Tumor targetability and antitumor effect of docetaxel-loaded hydrophobically modified glycol chitosan nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2008;128:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immordino ML, et al. Preparation, characterization, cytotoxicity and pharmacokinetics of liposomes containing docetaxel. J Control Release. 2003;91:417–29. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabr-Milane LS, et al. Multi-functional nanocarriers to overcome tumor drug resistance. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez MA, et al. Evidence that polyunsaturated lecithin induces a reduction in plasma cholesterol level and favorable changes in lipoprotein composition in hypercholesterolemic rats. J Nutr. 1990;120:659–67. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziara JM, et al. Blood compatibility of cetyl alcohol/polysorbate-based nanoparticles. Pharm Res. 2005;22:1821–8. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-7547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le UM, et al. Tumor chemo-immunotherapy using gemcitabine and a synthetic dsRNA. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:440–7. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.3.5423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, et al. The antitumor effect of novel docetaxel-loaded thermosensitive micelles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;69:527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lixin W, et al. A less irritant norcantharidin lipid microspheres: formulation and drug distribution. Int J Pharm. 2006;323:161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyuksel H, et al. Nanomicellar paclitaxel increases cytotoxicity of multidrug resistant breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;274:327–30. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyewumi MO, et al. Comparison of cell uptake, biodistribution and tumor retention of folate-coated and PEG-coated gadolinium nanoparticles in tumor-bearing mice. J Control Release. 2004;95:613–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritger PL, Peppas NA. A simple equation for description of solute release II. Fickian and anomalous release from swellable devices. Journal of Controlled Release. 1987;5:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Tije AJ, et al. Pharmacological effects of formulation vehicles: implications for cancer chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:665–85. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauthier C, et al. Drug delivery to resistant tumors: the potential of poly(alkyl cyanoacrylate) nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2003;93:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade A, Weller PJ. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients. American Pharmaceutical Association and The Pharmaceutical Press 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Williams KJ, et al. Intravenously administered lecithin liposomes: a synthetic antiatherogenic lipid particle. Perspect Biol Med. 1984;27:417–31. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1984.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, et al. The performance of docetaxel-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles targeted to hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomaterials. 2009;30:226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, et al. Inhibitory effects of beraprost on platelet aggregation: comparative study utilizing two methods of aggregometry. Thromb Res. 1999;94:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(98)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zbinden G, et al. Assessment of thrombogenic potential of liposomes. Toxicology. 1989;54:273–80. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(89)90063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]