Abstract

Previous reports have shown that CO2 dissolved in xylem sap in tree stems can move upward in the transpiration stream. To determine the fate of this dissolved CO2, the internal transport of respired CO2 at high concentration from the bole of the tree was simulated by allowing detached young branches of sycamore (Platanus occidentalis L.) to transpire water enriched with a known quantity of 13CO2 in sunlight. Simultaneously, leaf net photosynthesis and CO2 efflux from woody tissue were measured. Branch and leaf tissues were subsequently analysed for 13C content to determine the quantity of transported 13CO2 label that was fixed. Treatment branches assimilated an average of 35% (SE=2.4) of the 13CO2 label taken up in the treatment water. The majority was fixed in the woody tissue of the branches, with smaller amounts fixed in the leaves and petioles. Overall, the fixation of internally transported 13CO2 label by woody tissues averaged 6% of the assimilation of CO2 from the atmosphere by the leaves. Woody tissue assimilation rates calculated from measurements of 13C differed from rates calculated from measurements of CO2 efflux in the lower branch but not in the upper branch. The results of this study showed unequivocally that CO2 transported in xylem sap can be fixed in photosynthetic cells in the leaves and branches of sycamore trees and provided evidence that recycling of xylem-transported CO2 may be an important means by which trees reduce the carbon cost of respiration.

Keywords: Corticular photosynthesis, CO2 recycling, dissolved CO2, woody tissue respiration, xylem

Introduction

The CO2 concentration of air equilibrated with xylem sap inside tree stems is much higher than the atmospheric CO2 concentration. It can range from <1% to >26%, but is most commonly measured between 3% and 10% (Teskey et al., 2008). Previous reports have shown that dissolved CO2 in the xylem sap is carried upward in the stem when trees are transpiring (Teskey and McGuire, 2002), suggesting that the CO2 in xylem sap is a mixture of CO2 released by respiration of local tissues and CO2 transported from soil, roots, and lower in the stem (Teskey and McGuire, 2007). A direct correlation between CO2 efflux from stems into the atmosphere and the CO2 concentration in the xylem sap has also been observed, which indicates that a portion of the dissolved CO2 in xylem sap diffuses outward to the atmosphere (Teskey and McGuire, 2005).

Assimilation of internally-sourced CO2 by woody tissues has been described as a recycling mechanism by which trees can recapture some of the CO2 released by respiration (see review by Pfanz et al., 2002). This mechanism has been termed ‘corticular photosynthesis’, implying that the assimilation occurs in the cortical tissue just below the bark, although some reports have shown that chlorophyll can be found in deeper tissues (Langenfeld-Heyser, 1989; Van Cleve et al., 1993; Berveiller et al., 2007). Corticular photosynthesis has usually been measured by gas exchange and calculated as the reduction of CO2 efflux to the atmosphere in the light compared to efflux in the dark (Foote and Schaedle, 1976; Cernusak and Marshall, 2000; Wittmann et al., 2006). This calculation assumes that all CO2 generated in woody tissue fluxes outward to the atmosphere if it is not refixed in cortical tissues. However, CO2 can also move by mass flow in xylem sap, and gas exchange measurements do not account for this internally transported CO2 (McGuire et al., 2007).

Many questions remain unanswered concerning the ultimate fate of dissolved CO2 at high concentration in xylem sap when it is transported from stems into smaller branches. For example, some dissolved CO2 may be refixed by photosynthesizing cells in the woody branch tissues and some may ascend to the leaves and be refixed there. A few studies have reported on the assimilation of internal CO2 using methods other than gas exchange. Wiebe (1975) showed that excised slivers of both primary and secondary xylem of several tree species exposed to air enriched with 14CO2 could photosynthesize. With 14CO2 dissolved in water it was shown that excised leaves were capable of fixing CO2 that was transported in the xylem sap from the petiole into the leaf (Stringer and Kimmerer, 1993). Hibberd and Quick (2002) provided 14C-labelled carbon to roots and xylem of two herbaceous species and subsequently found the assimilated label throughout the plants. Ford et al. (2007) applied 13C-enriched dissolved inorganic carbon to the soil environment of Pinus taeda seedlings and subsequently found the label in root, stem, and leaf tissue, but the length of the experiment (4–6 weeks) precluded the ability to determine whether the carbon transported in the xylem stream was fixed directly in the stems or if it was fixed elsewhere first and transported as carbohydrate to the stems. Thus, it has not been directly shown that woody tissues can fix xylem-transported CO2, either in the xylem itself or as it diffuses outward though cortical tissues, nor has the rate of this fixation been determined.

The objective of this study was to determine if, where, and to what extent a xylem-transported pulse of CO2 was fixed by woody branch and leaf tissues versus how much diffused into the atmosphere. To simulate the transport of xylem sap at high [CO2] from stems into branches, detached young green branches of sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) were allowed to transpire water enriched with a known quantity of 13CO2 in sunlight. Simultaneously, leaf net photosynthesis and CO2 efflux from woody tissue were measured. After the uptake and measurement period in the light, the branches were placed in the dark and CO2 efflux from woody tissue was again measured. At the end of the experiment the branch and leaf tissues were analysed for excess 13C content to determine the quantity of transported 13CO2 label that was assimilated and retained in the tissues.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Two-year-old green branches were collected from coppiced sycamore trees growing at Whitehall Forest, a research forest of the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia, USA. The branches were collected at 08.00 h on 8 July 2005. They were 1.0–1.5 m long and ≤1 cm diameter and were selected such that leaves were evenly distributed along the branches from bottom to top. The branches were severed from the trees and their cut ends were placed immediately in water and recut to prevent embolisms in the xylem. The cut end of each branch was then placed in a 500 ml glass bottle containing 400 ml water enriched with CO2. The headspace in the bottles was minimal, due to displacement by the branches.

CO2 labelling

Water in the bottles was enriched with either 13CO2 (13C treatment, 18 bottles) or CO2 with atmospheric isotope composition (control, 6 bottles). To produce the 13C-labelled treatment water, a 10 l polycarbonate bottle was completely filled with deionized water and sealed. The 10 l bottle was fitted with two outlets, one near the bottom and one in the lid. The top outlet was connected with tubing to a tank of compressed 100% CO2 at 99 atom% 13C (ICON Services, Summit, New Jersey USA) and the bottom outlet was fitted with tubing routed to a drain. The outlets were opened and 2.0 l of the water was displaced with CO2 from the tank. The tubing from both outlets was then connected to a small pump which circulated the CO2 through the water in a closed loop. After 3 h the water was transferred to the 500 ml glass bottles, which were sealed and stored at 4 °C until the following morning when the experiment was conducted. The same procedure was used to produce the control treatment water using a tank of compressed 100% CO2 at atmospheric isotope composition (∼1 atom% 13C) (National Welders Supply, Toccoa, Georgia USA). The CO2 concentration ([CO2]) of the labelled and control water was 26.9% and 26.6% (0.0116 and 0.0114 mol l−1), respectively, as measured with a CO2 microelectrode (model MI-720, Microelectrodes Inc., Bedford, New Hampshire USA).

Experimental set-up

After placing the branches into the CO2-enriched water, the tops of the bottles were immediately sealed with closed-cell foam gaskets and wrapped with parafilm to minimize diffusion of CO2 to the atmosphere. The bottles were then placed 30 cm apart in three wooden racks designed to support them securely. Each rack held six treatment branches and two control branches and the treatment and control bottles were arranged randomly within each rack. Control branches were placed among the treatment branches to determine if any 13CO2 label that might diffuse from the treatment bottles or flux to the atmosphere from the treatment branches could enter the leaves through the stomates and be assimilated in the leaves. The racks were placed outdoors in a shade house fitted with 50% shade cloth at the greenhouse facilities of the University of Georgia School of Forestry and Natural Resources in Athens, Georgia, USA. Prior to the start of measurements, the branches transpired for ∼2 h to allow the CO2-enriched water to reach the leaves. In a simultaneous experiment, additional sycamore branches of similar size were placed in water containing food colouring and allowed to transpire in the same location under the 50% shade cloth. The colouring was clearly visible in the leaves within 30 min, and within 1 h the leaves were saturated with colour, indicating that 2 h was sufficient time for internal transport of CO2 to the leaves.

Leaf and branch gas exchange measurements

Beginning at 10.00 h, leaf net photosynthesis and branch CO2 efflux were measured on half of the branches in each rack (total of nine treatment and three control branches). Leaf net photosynthesis was measured on two fully expanded leaves in the middle part of each branch with a portable photosynthesis system (model LI-6400, Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska USA). Measurements were made at ambient temperature, light, and humidity conditions. To measure branch CO2 efflux, a 2.5 cm diameter×4 cm long cylindrical clear polycarbonate cuvette was placed around the branch, sealed with closed cell foam gaskets and flexible rubber sealant (Qubitac, Qubit Systems Inc, Kingston, Ontario, Canada), and secured with cable ties. Compressed air of known near-ambient [CO2] was supplied from a cylinder to the cuvette at 0.5 l min−1 with a mass flow controller (model FMA5514; Omega Engineering Inc., Stamford, Connecticut USA). An infrared gas analyser (IRGA) (model LI-7000, Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska USA) measured the [CO2] of air leaving the cuvette. The IRGA was operated in open configuration (Long and Hallgren, 1985). Efflux measurements were made at two locations on each branch (lower, ∼25 cm from the cut end, and upper, ∼60 cm from the cut end). The portions of the branches that were enclosed in the cuvette were marked for later weighing. Air temperature during the measurement period was ∼32–35 °C and the sky was clear. Photosynthetically active radiation in the shade house during the experiment, measured with the quantum sensor of the LI-6400, averaged 575 μmol m−2 s−1.

When efflux measurements in the light were complete (at 12.45 h), the same 12 branches were moved into a nearby dark room. The temperature in the room was maintained at ∼ 35 °C. The branches were allowed to equilibrate to the new conditions for ∼2 h; efflux measurements were then repeated on each branch.

Stable isotope sampling

At the end of the water uptake period (12.45 h), the branches not used for gas exchange measurements (nine treatment and three control branches) were removed from the CO2-enriched water. The amount of enriched water taken up by each plant was recorded. These branches were transferred to 500 ml bottles containing deionized water at atmospheric [CO2] and left in the shade house for an additional 4 h to permit time for assimilation of 13C label that remained in the branches. Each branch was then removed from the water, placed in a large plastic bag, and transferred into an ultra-low temperature freezer at –60 °C to stop all metabolic activity.

The branches used for efflux measurements were removed from the enriched water after measurements in the dark were complete. The amount of water taken up was recorded, and the branches were frozen in the same manner described above. After at least 20 min at –60 °C, all branches were moved to a laboratory freezer and stored at –9 °C.

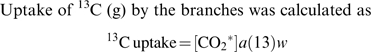

Uptake of 13C (g) by the branches was calculated as

|

(1) |

where [CO2*] is total dissolved carbon (mol l−1) calculated using Henry's coefficients (Butler, 1991; McGuire and Teskey, 2002), a is atom% 13C and w is water uptake of the branch (L).

Each branch was thawed individually and separated into the following parts: leaves, petioles, stipules, immature new growth (consisting of apical branch tips and small newly-emerged leaves), upper branch woody tissue, and lower branch woody tissue. Upper and lower branch samples were taken at the same height as the earlier efflux samples (∼60 cm and 25 cm from the cut end, respectively). The leaf area of each branch was measured with an area meter (model LI-3100, Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska USA). A subsample of three mature leaves from each branch was further separated by excising the tripalmately-branched major vein from the remaining tissue. Subsamples of upper and lower woody tissue from each branch were separated into xylem and cortex tissues. All samples and subsamples were dried in an oven at 65 °C for 72 h and weighed on a balance. Woody tissue efflux was calculated on a mass basis (μmol g−1 s−1). Net photosynthesis measurements made on a leaf area basis (μmol m−2 s−1) were converted to a leaf tissue mass basis (μmol g−1 s−1). Samples and subsamples were ground to a fine powder in a ball mill (model 8000-D, SPEX CertiPrep Inc, Metuchen, New Jersey, USA), packaged in glass bottles, and sent to Idaho Stable Isotopes Laboratory at the College of Natural Resources of the University of Idaho (ISIL), Moscow, Idaho, USA for analysis.

Stable isotope analysis

At ISIL, 2.0 mg of each sample was packed in a tin cup for isotopic analysis. Sample δ13C was measured with a continuous flow, isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany). Standard deviations of internal standards were less than 0.1‰. The isotopic composition of the dissolved CO2 pool supplied to the branches was completely dominated by the added CO2 and the δ13C in the treatment branches was so high that fractionations were not a concern. The ratio of excess 13C to 12C in each sample was calculated as

| (2) |

where δ13CMEAS is sample δ13C, 0.0112372 is the ratio of 13C/12C in the PDB standard, and –27 is the average δ13C of C3 plant tissue.

The amount of 13C fixed in each tissue was calculated as

| (3) |

where t is the dry weight of the tissue.

To facilitate comparisons of rates of carbon assimilation calculated from isotope data with rates calculated from measurements of gas exchange, 13C measured in the tissues were converted to 13CO2 by dividing by the ratio of the atomic weight of 13C to the atomic weight of 13CO2 (.29). The rate of assimilation of the 13CO2 label by the tissues was expressed on a mass basis (μmol 13CO2 g−1 tissue s−1).

Data processing and statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the concentration of 13CO2 in treatment versus control branches and between the treatment branches at the end of the light period versus the end of the dark period. ANOVA was also used to compare rates of leaf net photosynthesis in treatment versus control branches. A t test was used to determine if the amount of 13CO2 label fixed in tissues of control branches was different from zero. Linear regression was used to determine the relationship between woody tissue photosynthesis in the light and in the dark. All analyses were performed using SigmaStat 3.5 and SigmaPlot 11.0 software (Systat Software Inc, San Jose, California, USA).

Results

Efficacy of treatment

Transpiration, calculated from water uptake and leaf area data, averaged 2.1 mmol m−2 s−1, which was similar to average rates in young sycamore trees in situ found by Tang and Land (1995). Average water uptake was 234 ml (SE=16) for the treatment branches and 227 ml (SE=14) for the control branches. Average dissolved 13CO2 label uptake was 34.9 mg (SE=2.5) for the treatment branches and 0.33 mg (SE=0.02) for the control branches. Isotope analysis detected excess 13C in all treatment branch tissues. Mean δ13C (‰) in the treatment branches ranged from 209.6 in the lower cortex to –24.5 in the immature new growth. For reference, mean values in the control branches ranged from –26.2 in the upper xylem to –28.2 in the leaf lamina. Overall mean δ13C in the control branches was –26.9. On a mass basis, fixation of the 13CO2 label in the treatment branches ranged from an average of 0.1 mg g−1 in the immature new growth to 9.1 mg g−1 in the lower cortex (data not shown). The concentration of 13CO2 in the treatment branch tissues was significantly higher than in the control tissues (P <0.001). There were no significant differences in 13C concentration of any tissues between the treatment branches harvested at the end of the light period and those harvested after the additional 4.75 h in the dark (P=0.071–0.939).

Efficiency of 13CO2 label assimilation

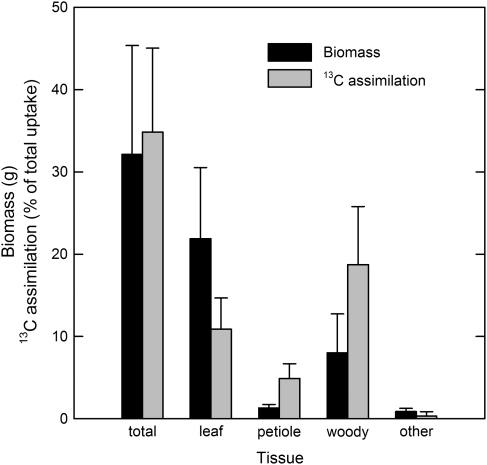

The treatment branches assimilated an average of 35% (SE=2.4) of the internally-transported 13CO2 label (Fig. 1). Of this total, over half was assimilated in the branch cortex and xylem, even though woody tissue composed just 25% of the total branch biomass. The petioles accounted for 5% of total 13CO2 label assimilation. The leaf tissue assimilated 31% of the transported 13CO2 label. Of that amount about one-third was assimilated by the major vein of the leaf, even though it comprised just 8% of total leaf biomass.

Fig. 1.

Mean biomass and assimilated portion of total 13C taken up by 18 detached sycamore branches allowed to transpire 13CO2-labelled water for 4.75 h in sunlight. One-half of the branches were harvested at the end of the uptake period, and one-half were harvested after an additional 4.75 h in the dark. (Pooled data shown.) Leaf tissue includes whole leaf, and vein and lamina subsamples. Woody tissue includes whole branch woody tissue, and upper and lower cortex and xylem subsamples. Other tissue includes stipule and new growth. Bars are standard error of the mean.

Rates of assimilation

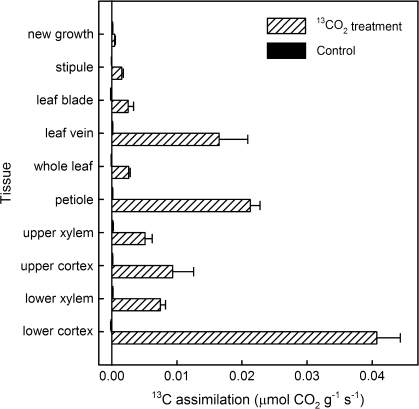

Internally transported 13CO2 label was assimilated at various rates by the tissues of the treatment branches, ranging from a negligible rate in new growth at the tip of the branch to 0.04 μmol g−1 s−1 in the lower branch cortex (Fig. 2). The highest rate of fixation of the 13CO2 label occurred in the cortex of the lower part of the branch. High rates of fixation were also observed in the petioles and leaf veins, indicating that the 13CO2 label was transported from the woody tissues of the branch into the leaves. Fixation of the 13CO2 label also occurred in the xylem tissue. The xylem was visibly green in colour, indicating the presence of chlorophyll and suggesting that photosynthesis was possible. The rate of assimilation of the 13CO2 label by the control branches was not significantly different from zero (t=0.774, P=0.440, n=66, pooled data of all tissues) indicating that any 13CO2 label that may have escaped from the treatment system into the atmosphere was not incorporated into other branches in detectable quantities. The average rate of internal fixation of the 13CO2 label of all tissues of the treatment branches was 0.01 μmol g−1 s−1. Leaf net photosynthesis of atmospheric CO2 measured by gas exchange averaged 0.16 μmol CO2 g−1 s−1 (SE=0.01) and was not significantly different between treatment and control branches (P=0.716). Total branch assimilation of internally-transported 13CO2 label over the entire experiment averaged 3.1 mmol branch−1 (SE=0.02), while leaf assimilation of atmospheric CO2 averaged 52.2 mmol branch−1 (SE=7.8). Overall, the total assimilation of the internally transported 13CO2 label was 6% of the assimilation of CO2 from the atmosphere.

Fig. 2.

Mean rates of internal 13CO2 label assimilation of tissues of detached sycamore branches after 4.75 h water uptake in sunlight as determined by 13C analysis. One-half of the branches were harvested at the end of the uptake period, and one-half were harvested after an additional 4.75 h in the dark. (Pooled data shown.) Treatment branches (n=18) were labelled by allowing them to take up water enriched with 99 atom% 13CO2 at a concentration of 0.0116 mol l−1. Control branches (n=6) took up water enriched with 0.0114 mol l−1 CO2 at atmospheric isotope composition (∼1 atom% 13C). Bars are standard error of the mean. Control branch assimilation of 13CO2 was not significantly different from zero (t=0.774, P=0.440, n=66, pooled data of all tissues).

Comparison of rates of woody tissue photosynthesis calculated from efflux measurements and from 13C analysis

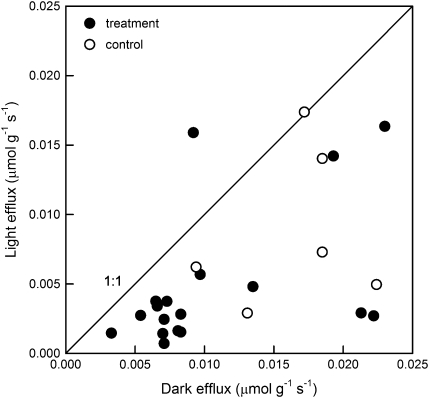

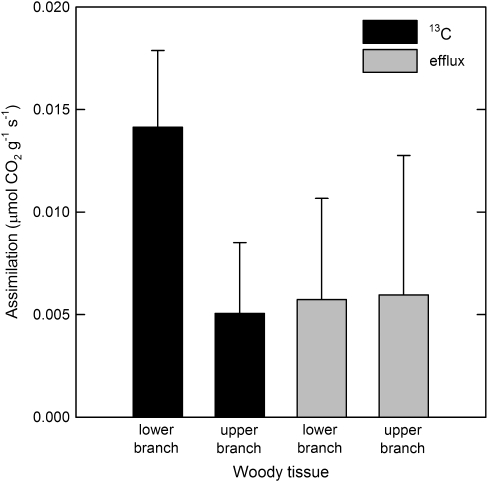

The difference between CO2 efflux measurements made in the dark and light was used to estimate the rate at which carbon was assimilated photosynthetically in the woody tissue of the branches (Fig. 3). Rates of dark efflux ranged from 0.003 to 0.023 μmol CO2 g−1 s−1. There was a weak positive correlation between efflux in the light and in the dark (light efflux=0.000621+0.430 (dark efflux), R2=0.23, P=0.011). On average, woody tissue photosynthesis in the light reduced CO2 efflux from the branch by about 52% (SE=0.07). Net assimilation based on CO2 efflux measurements was not significantly different between treatment and control branches (P=0.505). Assimilation of transported 13CO2 label by woody tissues calculated by 13C analysis was 130% greater than assimilation of CO2 calculated from efflux measurements in the lower part of the branches (Fig. 4). The difference between the upper and lower woody tissue assimilation rates seen in the 13C-based data was not observed in the efflux-based measurements.

Fig. 3.

Woody tissue CO2 efflux of detached sycamore branches calculated from measurements made with an infrared gas analyser. Each branch was measured at two locations (lower, ∼25 cm from the cut end, and upper, ∼60 cm from the cut end). Measurements were made in sunlight after branches took up CO2-enriched water for at least 2 h, and repeated after the branches equilibrated in the dark for at least 2 h. Treatment branches (n=9) took up water enriched with 99 atom% 13CO2 at a concentration of 0.0116 mol l−1. Control branches (n=3) took up water enriched with 0.0114 mol l−1 CO2 at atmospheric isotope composition (∼1 atom% 13C). Light efflux was significantly different from dark efflux (t=3.731, P=<0.001, n=24), and light efflux was weakly correlated with dark efflux (light efflux=0.000621+0.430 (dark efflux), R2=0.23, P=0.011).

Fig. 4.

CO2 assimilation of detached sycamore branches allowed 13CO2-labelled water to transpire for 4.75 h in sunlight. Each branch was measured at two locations (lower, ∼ 25 cm from the cut end, and upper, ∼ 60 cm from the cut end). Assimilation was determined by two methods, 13C analysis and efflux calculated from measurements made with an infrared gas analyser. Efflux measurements were made in sunlight after the branches had taken up CO2-enriched water for at least 2 h, and were repeated after the branches equilibrated in the dark for at least 2 h. Branches were harvested after 4.75 h in the dark for 13C analysis.

Discussion

These results showed that CO2 transported in xylem sap can be assimilated in the leaves and branches of sycamore trees. The branches rapidly absorbed the CO2-enriched water and the 13C label was subsequently detected in all parts of the treatment branches, but not in the control branches. The absence of assimilated 13CO2 in the tissues of the control branches indicated that little, if any, of the 13CO2 label that escaped from the system entered the leaves through the stomates.

The branches assimilated about one-third of the 13CO2 pulse supplied to the xylem, indicating that a substantial amount of recycling of internal CO2 could be occurring in branches. This experiment showed the capacity for refixation under one set of circumstances. In situ, the amount of internal CO2 that can be refixed depends on many factors including the capacity for photosynthesis in woody tissues, barriers to CO2 diffusion through the bark, internal [CO2], the rate of sap flow, and incident light levels.

This experiment was conducted under 50% shade cloth because excised branches in a pilot study wilted in full sun. The experimental branches were possibly acclimated to higher irradiance in situ, so the low light levels under the shade cloth may have reduced woody tissue photosynthesis to less than its potential maximum. For example, Cernusak and Marshall (2000) found increases in woody tissue photosynthesis with increasing light up to >2000 μmol PAR m−2 s−1 in Pinus monticola branches.

In this experiment, the rate of radial CO2 diffusion from woody tissues to the atmosphere appears to have been much greater than the photosynthetic capacity of the tissues. This idea was supported by the low concentration of 13C found in the leaves compared to the other tissues, which indicates that very little xylem-transported 13CO2 label reached the leaf tissue, even though only one-third of the label was assimilated. The rate of assimilation of the 13CO2 label was greatest in the lower branch cortex, intermediate in the upper branch cortex, and least in the immature new growth at the top of the branch. These differences suggest that there may have been differences in the photosynthetic capacity of the different tissues along the branch or, more likely, that the 13CO2 label concentration of the sap may have decreased as it travelled upward in the branch.

Assimilation of the 13CO2 label by woody tissues was lower in the upper branch compared to the lower branch and was negligible in the leaf lamina, which was most distal to the source of the label. This reduction in assimilation with distance from the source may have been caused by a reduction, due to assimilation and outgassing, in the concentration of dissolved 13CO2 label in the treatment water as it ascended in the branch. The pulse of 13CO2 provided to the branches in this experiment may mimic the transport of sap at high [CO2] from large woody stems into smaller branches in situ, where a similar reduction in [CO2] with distance may occur. However, since some of the dissolved CO2 in the xylem is supplied from the respiration of tissues along the entire length of the branch and our 13CO2 measurements did not account for any assimilation of this CO2, the contribution of woody tissue assimilation to tree carbon balance in situ may be greater than the 6% found in this study. Alternatively, if the amount of CO2 transported in the xylem sap from stems into branches is lower in situ than the amount of 13CO2 label provided to the branches in this study, then the contribution of woody tissue assimilation of transported CO2 in situ may be lower than what was found here.

In addition, in this study the pH of the unbuffered treatment water (∼5.8) may have been low enough to acidify the protoplasm of the cells in the woody tissue directly, or the high [CO2] may have indirectly caused a similar acidification, leading to a reduced capacity for assimilation by these tissues (Manetas, 2004).

Within the leaves, it appeared that most of the remaining 13CO2 label was scavenged from the flowing sap before it reached the mesophyll because the highest rate of assimilation occurred in the tissue proximal to the source of the 13CO2 label (the petioles), and the lowest rate occurred in the tissue distal to the source (the leaf blade), with an intermediate rate in the leaf veins. These results agree with the findings of Stringer and Kimmerer (1993), who used 14CO2 as a tracer to determine the assimilation of xylem-transported carbon in detached Populus deltoides leaves and found that 53.7% of the label was fixed in the petiole and almost all of the remaining label (43.0%) was fixed in the primary and secondary leaf veins. Only a small amount was fixed in the leaf mesophyll.

Both species, sycamore in this study and cottonwood in Stringer and Kimmerer's (1993) study, have heterobaric leaves with bundle sheath extensions (McClendon, 1992), suggesting that, when the enriched water reached the leaves, labelled CO2 that might have outgassed into intercellular air spaces would have diffused very slowly into the mesophyll. Homobaric leaves, on the other hand, may exhibit a different pattern of fixation of xylem-transported CO2 because they have greater potential for CO2 diffusion from the veins across the mesophyll.

It was expected that the 13CO2 concentration of the tissues would decrease when the branches were allowed to respire in the dark after the uptake period in the light, but no significant loss of the label was detected after the dark period. This observation may indicate that CO2 fixed in the woody tissues did not turn over rapidly (was not re-respired), even at a high temperature (35 °C) that promoted a high rate of respiration. These results are not entirely surprising, and agree with other reports that suggest a time lag between photosynthate production and respiration (Knohl et al., 2005). In addition, the lack of difference in 13CO2 concentration between the tissues harvested after the light and dark periods supports the idea that the assimilation was substantially light-driven and not the result of other non-photosynthetic processes. However, analysis of extracted carbohydrates would be required to verify the specific pathway of assimilation.

On a whole-branch basis, internal assimilation of xylem-transported 13CO2 label averaged 6% of the atmospheric CO2 assimilation by the leaves. Thus, assimilation of xylem-transported CO2 appeared to account for only a small proportion of total branch carbon gain. However, differences in branch morphology, canopy architecture, or amount of chlorophyll in non-leaf tissues could produce different ratios of internal CO2 assimilation compared to leaf atmospheric CO2 assimilation. For example, branches with a lower leaf density could have a higher ratio of internal to atmospheric assimilation than branches with relatively more leaves. The effect of leaf density on this ratio was demonstrated; a direct linear relationship was found between the ratio of non-leaf mass to leaf mass and the ratio of internal (non-leaf) 13CO2 label assimilation to leaf atmospheric CO2 assimilation (internal:leaf assimilation ratio=0.0152+0.0008 non-leaf:leaf mass ratio), R2=0.52, P=0.018). The importance of non-leaf assimilation of internally generated CO2 to total carbon balance could also change seasonally and even diurnally and could increase due to conditions that limit leaf photosynthesis, such as heat or water stress, seasonal leaf senescence, and insect or disease damage (Bossard and Rejmanek, 1992).

Both methods used to determine the internal rates of assimilation in this experiment were inadequate. Assimilation rates calculated from an analysis of the 13C in the tissues were a direct measure of assimilation of the xylem-transported 13CO2 label, but were not a measure of total assimilation in these branches because the 13C-based rates did not account for any assimilation of the 12CO2 produced by respiring woody tissues and, therefore, underestimated the actual assimilation of internally-sourced CO2. On the other hand, assimilation calculated from measurements of CO2 efflux from woody tissues cannot distinguish the source of the CO2 and do not account for the mass-flow movement of CO2 in the xylem, either in this experiment or in situ.

In this experiment, there was another source of error in the efflux-based measurements of assimilation due to the introduction of the 13CO2 label. The infrared absorption spectra for 12CO2 and 13CO2 are considerably different and the IRGA is sensitive to only ∼1/3 of the 13C spectrum (McDermitt et al., 1993). Therefore, the amount of 13CO2 diffusing from the woody tissues during measurements in both the light and in the dark was possibly underestimated. A rough approximation of the amount of this underestimation was calculated. Only a portion (average 3.1 mmol, 35%) of the 13CO2 label taken up in the treatment water was assimilated. Based on tissue mass it is estimated that ∼2.0% of the unfixed 13CO2 label remained in the branch in non-leaf tissue in the dissolved or gaseous state; it was assumed that the balance (average 5.5 mmol, ∼63%) fluxed to the atmosphere from non-leaf tissue. Thus, from this assumption it is estimated that the rate of loss to the atmosphere of 13CO2 would have averaged 0.0165 μmol g−1 s−1 across all non-leaf tissues (average 8.8 g) over the 10.5 h of the experiment. Therefore, it is likely that efflux was underestimated by ∼0.0110 μmol g−1 s−1 on average. Efflux-based rates of assimilation were similar in the lower and upper parts of the branches, but the underestimation may have differed between the upper and lower parts of the branch. Compared to the efflux-based rates, the 13C-based rates of assimilation were similar in the upper branch, but substantially higher in the lower branch, suggesting that most of the 13CO2 label taken up by the branches was assimilated or fluxed to the atmosphere before it reached the upper parts of the branches. If this interpretation is correct, then the efflux-based rate of woody-tissue assimilation was underestimated due to the IRGA characteristics to a greater degree in the lower part of branch than in the upper part.

An assumption made in stem and branch gas exchange measurements is that CO2 respired by woody tissues fluxes rapidly to the atmosphere in the dark and, in the presence of light, some of this CO2 can be reassimilated by chlorophyll-containing woody tissues. Therefore, photosynthesis by woody tissues in stems and branches has typically been estimated by comparing CO2 efflux in the light with efflux in the dark; the difference is deemed to be the assimilation rate. However, unlike leaf photosynthesis, where gas exchange directly measures the amount of CO2 removed from the surrounding air, measurement of woody tissue photosynthesis by this method is only an indirect estimate because these tissues fix CO2 that is generated internally. The direction of movement of the CO2 released by respiration of woody tissues can be inward or upward as well as outward, so gas exchange measurements may not accurately estimate the amount of carbon that is fixed by stems or branches because they do not account for the internal movement of CO2.

The effects of sap velocity may also contribute to the inadequacy of efflux measurements for estimating woody tissue photosynthesis. An increase in sap velocity has been shown to decrease CO2 efflux by diluting the [CO2] of the xylem, thereby decreasing the CO2 concentration gradient from the xylem to the atmosphere (McGuire et al., 2007). This effect was demonstrated under controlled conditions in the laboratory, but should also be true in situ because soil water is at much lower [CO2] than xylem sap (Teskey and McGuire, 2007). Therefore, a change in CO2 efflux, if accompanied by a change in sap velocity, may not be evidence of increased or decreased assimilation. However, in this study, a high concentration of CO2 was supplied in the water taken up by the branches, so dilution should not have occurred with increased sap velocity.

Most previous reports suggest that woody tissue photosynthesis occurs in the cortex. However, green tissue can be observed in the xylem of many woody plant species and chlorophyll has been reported in the xylem and pith of several herbaceous and woody species (Pfanz et al., 2002; Armstrong and Armstrong, 2005; Dima et al., 2006; Berveiller et al., 2007). Chlorophyll-containing pith cells of young poplar were found to be capable of fixing 14CO2 in the light (Van Cleve et al., 1993). Sun et al. (2005) found that light penetrated the periderms of stems of herbaceous species and was transmitted both radially and axially, even in stems with secondary growth. In the current study, analysis of tissue subsamples showed that the xylem was responsible for 42% of the total assimilation of the 13CO2 label by the woody branch tissues. This proportion was similar for both lower and upper tissue subsamples (41% and 44%, respectively) even though the amount of 13CO2 label fixed in the lower branch was ∼six times greater than in the upper branch (data not shown) and the assimilation rate on a mass basis was substantially higher in the lower cortex tissue compared to the xylem and upper cortex tissues (Fig. 2). The discrepancy between the assimilation rates and proportions of 13C fixed can be explained by the difference in the ratio of cortex to xylem tissue between the lower (larger diameter) and upper (smaller diameter) parts of the branch, which changes in proportion to the difference in the surface area to volume ratio. The sycamore branches used in this study had visibly green xylem, so it is not surprising that carbon was fixed in the xylem. However, since most woody tissue photosynthesis is thought to occur in the cortex, the large amount of assimilated 13C found in the xylem was unexpected.

The results of this study provide evidence that a direct recycling mechanism for the recapture of transported CO2 exists in woody tissues. There has been speculation about the origin of this internal recycling process (Pfanz et al., 2002). It may have evolved directly as a mechanism to reduce the carbon cost of building and maintaining a large woody structure. More likely, it is retained from ancestral land-colonizing plant species that lacked organ differentiation and required all functions (dessication resisistance, support, transport, and photosynthesis) be performed by the same tissue (Kenrick and Crane, 1997; Boyce, 2008). Regardless of its origin, the internal recycling process must provide carbon benefits to the plant exceeding the investment in chlorophyll by woody tissues.

In conclusion, it has been shown unequivocally that dissolved CO2 can be transported through the xylem and into leaves and that this CO2 can be assimilated in both woody and leaf tissues. It was found that about one-third of the transported 13CO2 label was assimilated, with the remainder diffusing to the atmosphere, although these proportions are likely to vary substantially in situ among species, incident light levels, times of year, and degrees of environmental stress. Photosynthetic cells in woody tissues, petioles, leaf veins, and, to a lesser degree, leaf lamina, all contributed to the assimilation of the xylem-transported 13CO2 label. These results provide additional evidence that the retention and transport of CO2 in the xylem sap, coupled with woody tissue photosynthesis, may be a mechanism by which trees conserve and recycle a portion of the CO2 released by the respiration of woody tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Murphy and Carol Goranson for help with setting up and conducting the experiment, data processing, and sample processing. Funding for this project was provided by a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF Biological Sciences Division of Integrative Organismal Systems Grant 0445495).

References

- Armstrong W, Armstrong J. Stem photosynthesis not pressurized ventilation is responsible for light-enhanced oxygen supply to submerged roots of alder (Alnus glutinosa) Annals of Botany. 2005;96:591–612. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berveiller D, Kierzkowski D, Damesin C. Interspecific variability of stem photosynthesis among tree species. Tree Physiology. 2007;27:53–61. doi: 10.1093/treephys/27.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossard CC, Rejmanek M. Why have green stems? Functional Ecology. 1992;6:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce CK. How green was Cooksonia? The importance of size in understanding the early evolution of physiology in the vascular plant lineage. Paleobiology. 2008;34:179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Butler JN. Carbon dioxide equilibria and their applications. Chelsea, MI: Lewis; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Marshall JD. Photosynthetic refixation in branches of Western white pine. Functional Ecology. 2000;14:300–311. [Google Scholar]

- Dima E, Manetas Y, Psaras GK. Chlorophyll distribution pattern in inner stem tissues: evidence from epifluorescence microscopy and reflectance measurements in 20 woody species. Trees: Structure and Function. 2006;20:515–521. [Google Scholar]

- Foote KC, Schaedle M. Diurnal and seasonal patterns of photosynthesis and respiration by stems of Populus tremuloides Michx. Plant Physiology. 1976;58:651–655. doi: 10.1104/pp.58.5.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CR, Wurzburger N, Hendrick RL, Teskey RO. Soil DIC uptake and fixation in Pinus taeda seedlings and its C contribution to plant tissues and ectomycorrhizal fungi. Tree Physiology. 2007;27:375–383. doi: 10.1093/treephys/27.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd JM, Quick WP. Characteristics of C4 photosynthesis in stems and petioles of C3 flowering plants. Nature. 2002;415:451–454. doi: 10.1038/415451a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenrick P, Crane PR. The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature. 1997;389:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Knohl A, Werner RA, Brand WA, Buchmann N. Short-term variations in δ13C of ecosystem respiration reveals link between assimilation and respiration in a deciduous forest. Oecologia. 2005;142:70–82. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenfeld-Heyser R. CO2 fixation in stem slices of Picea abies (L.) Karst: microautoradiograph studies. Trees. 1989;3:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Hallgren J-E. Measurement of CO2 assimilation by plants in the field and in the laboratory. In: Coombs J, Hall DO, Long SP, Scurlock JMO, editors. Techniques in bioproductivity and photosynthesis. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press; 1985. pp. 62–94. [Google Scholar]

- Manetas Y. Probing corticular photosynthesis through in vivo chlorophyll fluorescence measurements: evidence that high internal CO2 levels suppress electron flow and increase the risk of photoinhibition. Physiologia Plantarum. 2004;120:509–517. doi: 10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClendon JH. Photographic survey of the occurrence of bundle-sheath extensions in deciduous dicots. Plant Physiology. 1992;99:1677–1679. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermitt DK, Welles JM, Eckles RD. Effects of temperature, pressure and water vapor on gas phase infrared absorption by CO2. Linclon, NE: Li-Cor, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire MA, Teskey RO. Microelectrode technique for in situ measurement of carbon dioxide concentrations in xylem sap of trees. Tree Physiology. 2002;22:807–811. doi: 10.1093/treephys/22.11.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire MA, Teskey RO, Cerasoli S. CO2 fluxes and respiration of branch segments of sycamore (Platanus occidentalis L.) examined at different sap velocities, branch diameters, and temperatures. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:2159–2168. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfanz H, Aschan G, Langenfeld-Heyser R, Wittmann C, Loose M. Ecology and ecophysiology of tree stems: corticular and wood photosynthesis. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:147–162. doi: 10.1007/s00114-002-0309-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer JW, Kimmerer TW. Refixation of xylem sap CO2 in Populus deltoides. Physiologia Plantarum. 1993;89:243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Yoda K, Suzuki H. Internal axial light conduction in the stems and roots of herbaceous plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2005;56:191–203. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ZM, Land SB. Photosynthesis and leaf water relations in 4 American sycamore clones. Forest Science. 1995;41:729–743. [Google Scholar]

- Teskey RO, McGuire MA. Carbon dioxide transport in xylem causes errors in estimation of rates of respiration in stems and branches of trees. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2002;25:1571–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Teskey RO, McGuire MA. CO2 transported in xylem sap affects CO2 efflux from Liquidambar styraciflua and Platanus occidentalis stems, and contributes to observed wound respiration phenomena. Trees: Structure and Function. 2005;19:357–362. [Google Scholar]

- Teskey RO, McGuire MA. Measurement of stem respiration of sycamore (Platanus occidentalis L.) trees involves internal and external fluxes of CO2 and possible transport of CO2 from roots. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2007;30:570–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teskey RO, Saveyn A, Steppe K, McGuire MA. Origin, fate and significance of CO2 in tree stems. New Phytologist. 2008;177:17–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cleve B, Forreiter C, Sauter JJ, Apel K. Pith cells of poplar contain photosynthetically active chloroplasts. Planta. 1993;189:70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe HH. Photosynthesis in wood. Physiologia Plantarum. 1975;33:245–246. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann C, Pfanz H, Loreto F, Centritto M, Pietrini F, Alessio G. Stem CO2 release under illumination: corticular photosynthesis, photorespiration or inhibition of mitochondrial respiration? Plant, Cell and Environment. 2006;29:1149–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]