Abstract

Parthenocarpy is potentially a desirable trait for many commercially grown fruits if undesirable changes to structure, flavour, or nutrition can be avoided. Parthenocarpic transgenic tomato plants (cv MicroTom) were obtained by the regulation of genes for auxin synthesis (iaaM) or responsiveness (rolB) driven by DefH9 or the INNER NO OUTER (INO) promoter from Arabidopsis thaliana. Fruits at a breaker stage were analysed at a transcriptomic and metabolomic level using microarrays, real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and a Pegasus III TOF (time of flight) mass spectrometer. Although differences were observed in the shape of fully ripe fruits, no clear correlation could be made between the number of seeds, transgene, and fruit size. Expression of auxin synthesis or responsiveness genes by both of these promoters produced seedless parthenocarpic fruits. Eighty-three percent of the genes measured showed no significant differences in expression due to parthenocarpy. The remaining 17% with significant variation (P <0.05) (1748 genes) were studied by assigning a predicted function (when known) based on BLAST to the TAIR database. Among them several genes belong to cell wall, hormone metabolism and response (auxin in particular), and metabolism of sugars and lipids. Up-regulation of lipid transfer proteins and differential expression of several indole-3-acetic acid (IAA)- and ethylene-associated genes were observed in transgenic parthenocarpic fruits. Despite differences in several fatty acids, amino acids, and other metabolites, the fundamental metabolic profile remains unchanged. This work showed that parthenocarpy with ovule-specific alteration of auxin synthesis or response driven by the INO promoter could be effectively applied where such changes are commercially desirable.

Keywords: fruit quality, fruit ripening, INO, parthenocarpic, seedless fruit, tomato

Introduction

Seeds are an undesirable feature in many fruits because they may have a hard or leathery texture, bitter taste, and in many instances accumulate harmful toxic compounds. Replacing seeds and seed cavities with edible fruit tissue is desirable (Varoquaux et al., 2000). Seedlessness is especially attractive in species with many seeds per fruit such as citrus, one large seed such as mango, or large cavities filled with numerous seeds such as melon and papaya. In tomato, seeds are in general not considered as a negative trait of fresh market fruits since they contribute in a positive way to the fruit taste. However, seedless fruits would be valuable and improve tomato processing.

Seed formation is an integral component of fruit development: developing seeds promote cell expansion via synthesis of auxin and other unknown molecules (Gillapsy et al., 1993). Metabolites associated with the developing embryo control the rate of cell division in surrounding fruit tissue, and seed number influences the final size and weight of fruit (Gillapsy et al., 1993). Thus, seedlessness is potentially associated with agronomically undesirable changes in quality.

Parthenocarpy is fruit set in the absence of fertilization. It can be induced with phytohormones, particularly auxins, and is currently used to increase fruit production under adverse conditions for fruit set and growth. Such methods are sometimes used in tomato, where they can cause malformed fruit and vegetative organs, inhibit further flowering, and usually yield poor quality fruit (Abad and Monteiro, 1989).

Genetic strategies offer effective approaches involving specific mutations or introduction of specific genes. In tomato, pat mutations that result in parthenocarpy increase gibberellic acid (GA) in ovules during development (Fos et al., 2001). Parthenocarpic fruit has also been generated through ovule-specific expression of the iaaM or iaaH genes from Agrobacterium tumefacians or the rolB gene from Agrobacterium rhizogenes, which affect auxin biosynthesis or response, respectively (Rotino et al., 1997; Carmi et al., 2003). Expression of IaaH in ovaries induced parthenocarpic fruit by hydrolysis of the auxin precursor naphthaleneacetamide (NAM) in the ovary. Parthenocarpic eggplant, tobacco, and tomato fruits were also obtained by expressing iaaM under the ovule-specific promoter DefH9 (Rotino et al., 1996; Ficcadenti et al., 1999; Donzella et al., 2000).

Expression of rolB under TRP-F1 (a promoter specific to ovaries and young fruit) induced parthenocarpy in tomato (Carmi et al., 2003). Parthenocarpic fruits have also been obtained with the silencing of SlIAA9 (before IAA4) (Wang et al., 2005) and SlARF7 (de Jong et al., 2009), and mutations in the ARF8 gene have been shown to induce parthenocarpic development in tomato (Goetz et al., 2007). However, most of the parthenocarpic fruits were heart-shaped and had a rather thick pericarp compared with wild-type fruits (de Jong et al., 2009). The challenge is to develop seedlessness by inducing parthenocarpy without needing supplemental pollination or application of plant growth regulators and without affecting fruit size and morphology. While the effect of the transgenic modifications on gross fruit morphology, productivity, and yield is known (Carmi et al., 2003), the effects on overall gene expression and metabolism in fruit are not known.

The aim of the present study was to address the following questions. Is the INNER NO OUTER (INO) promoter from Arabidopsis thaliana able to induce parthenocarpy in tomato? Can we avoid undesirable traits often associated with seedlessness such as loss of flavour or nutritional value? What changes result from seedlessness at a transcriptomic and metabolomic level? Which pathways show significant changes in seedless fruit compared with seeded fruit?

The first objective of this study was to verify whether expression of iaaM and rolB driven by the INO promoter could induce parthenocarpic fruits in tomato (cv MicroTom). The second objective was to determine changes in the transcriptome and metabolite profile induced by this genetic modification, comparing them with both wild-type fruits and transgenic parthenocarpic fruits obtained through ovule-specific expression of the same genes driven by the previously described ovule-specific promoter DefH9. The third objective was to determine any differences between transgenic and wild-type fruits in soluble solids content and other important morphological parameters.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Seeds of the tomato cultivar MicroTom were obtained from the Ralph M Parsons Foundation Plant Transformation Facility at UC Davis.

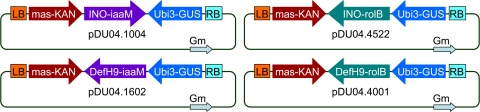

Plant binary vectors

Four plasmids were constructed, each containing one of two genes, iaaM and rolB, under the control of one of two ovary-specific promoters, DefH9 or INO (Fig. 1). iaaM was obtained by PCR of DNA obtained from the wild-type Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58 using primers derived from the NCBI sequence (NC003065). The forward primer with a KpnI site was GGTACCATGTCAGCTTCAGCTCTCCTTGATAACCAGTGC, and the reverse primer with an XbaI site was TCTAGATTAATTTCTATTGCGGTAGTTATATCTCTTCC. rolB was obtained by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of DNA obtained from wild-type Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain A4 using primers based on sequences published by Slightom et al. (1986). The forward primer with a HindIII site was GGAAGCTTATGGATCCCAAATTGCTATTCC. The reverse primer with a HindIII site was: GGAAGCTTTTAGGCTTCTTTCTTCAGGTTTACTGC. The DefH9 promoter was obtained from Anthirrhinum majus DNA using the forward primer AGGCGCGCCAATTCGGCACGAGGTCCCTTTCTATTTTTGCACAAAGCGTC and the reverse primer GGTACCGTACCTCAGAAAAATAACCTAATCATAATAAAC. These primers were based on the sequences of Spena et al. (2002). The above PCR products were TOPO cloned according to Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), and then DNA was isolated from selected clones (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and sequenced (Davis Sequencing, Davis, CA, USA). The INO promoter fragment was from pRJM71 (Meister et al., 2004). A cassette containing the INO promoter and nos terminator was made by deleting the INO cDNA from pRJM71. The iaaM and rolB genes were introduced into this cassette and then ligated into the binary vector pDU99.2215 (Escobar et al., 2001). The constructs were designated pDU04.1004 (INO-iaaM) and pDU04.4522 (INO-rolB). DefH9 constructs were made by cloning iaaM and rolB into cassettes containing the 35S promoter and ocs terminator. iaaM(rolB)-ocs was then blunt-end ligated into the TOPO-cloned DefH9 construct. The resulting DefH9/iaaM(rolB)-ocs cassette was then ligated into the binary pDU99.2215. The constructs were called pDU04.1602 (DefH9-iaaM) and pDU04.4001 (DefH9-rolB). These binary plasmids were then introduced into disarmed Agrobacterium EHA105 pCH32 as previously described (Wen-jun and Forde, 1989) to create a functional Agrobacterium vector for plant transformation.

Fig. 1.

The Agrobacterium binary vectors pDU04.1004 and pDU04.1602 control ovule-specific expression of the iaaM gene from Agrobacterium tumefaciens while pDU04.4522 and pDU04.4001 regulate ovule-specific expression of the rolB gene from Agrobacterium rhizogenes. The vectors pDU04.1004 and pDU04.4522 contain the novel INO ovule-specific promoter from Arabidopsis thaliana and vectors pDU04.1602 and pDU04.4001 contain the reference DefH9 promoter from Antirrhinum majus previously shown to display ovule-specific expression and pathenocarpy with iaaM from Pseudomonas syringae. Other common components present on all vectors include an nptII-selectable marker gene driven by the mannopine synthase 2 promoter (mas5) and a uidA scorable marker gene driven by the ubi3 promoter (ubi3). Arrows indicate the direction of transcription. LB and RB indicate the left and right T-DNA border sequences.

Tomato transformation

Tomato transformation was performed using MicroTom tomatoes following a modified version of the method described by Fillati et al. (1987). Primary parthenocarpic transformants (T0) were used for transcriptome and metabolite analysis and all transgenic plants were used for morphological measurements and soluble solids content.

Morphological analysis and soluble solid content

Fifteen fully ripe fruits from each transgenic plant and 10 from wild-type plants were picked for analysis of morphology and soluble solids content. Each fruit was weighed and the polar and equatorial diameter, number of locules, and seed number were determined. Brix value, an index of total solids content, was determined from juice squeezed from five separate fruits on each plant with a digital refractometer. Each fruit was also evaluated for shape malformation and colour of pulp. The data were analysed with an analysis of variance (ANOVA) univariate and ‘post hoc’ Duncan test (P=0.05) using SPSS software.

Experimental design and plant material

Gene expression profiles for breaker-stage fruits were generated for wild-type and parthenocarpic lines with the four transgenes. Wild-type fruits with seeds and wild-type fruits from which seeds had been removed were the controls. Three replicates (each one as a pool of eight fruits) were used for each treatment and control, except for DefH9-rolB, where only two replicates were available.

Microarrays were used to study gene expression patterns in parthenocarpic fruit. Wild-type fruit with seeds was compared with transgenic lines INO-iaaM, DefH9-iaaM, INO-rolB, and DefH9-rolB. To find genes with seed-specific expression, the control fruit were also compared with wild-type fruit from which seeds had been manually removed. There were three biological replicates for each treatment and control except DefH9-rolB, for which only two replicates were available. The metabolites present in parthenocarpic fruit were also studied, using each transgenic line as a separate treatment. Wild-type fruit with seeds were used as the control, and wild-type fruits with seeds manually removed were not considered. There were six replicates of each treatment and control group except DefH9-rolB, of which there were only five replicates.

RNA extraction

A modified hot borate method (Wan and Wilkins, 1994) was used to extract RNA from the pooled samples. Tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen and PVP-40 (200 mg) and put into a pre-chilled collection tube with 6–8 mg of proteinase K and 10 ml of 80 °C XT buffer (ratio 5 ml g−1).

Preparation of labelled RNA and hybridization

RNA labelling was performed according to instructions in the GeneChip One Cycle Target Labeling Kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Tomato microarrays were also purchased from Affymetrix. The array has 10 209 Solanum lycopersicum (preioulsy Lycopersicon esculentum) probe sets that interrogate >9200 S. lycopersicum transcripts. All fragmentation, hybridization, scanning, and image data processing were performed according to Affymetrix protocols.

Metabolomic analysis

For transgenes INO-iaaM, DefH9-iaaM, and INO-rolB, two fruits were taken from each of three different plants (representing three independent regeneration events), for a total of six replicates per transgene. For transgene DefH9-rolB, only two different plants with very few fruits were available and two fruits were taken from one plant and three from the other, for a total of five replicates. The transgenic seedless fruits were compared with wild-type seeded controls, two fruits each from six plants. Wild-type fruit without seeds was not analysed.

The replicate fruits were harvested at breaker stage, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C until analysis. For each sample, 20–50 mg of pulp was ground and 1 ml of pre-chilled extraction solvent (dH2O:MetOH:CHCl3 1:2.5:1) was rinsed with argon or gaseous nitrogen for 5 min and then added. After vortexing and centrifugation, the supernatant was analysed with a Pegasus III TOF (time-of-flight) mass spectrometer. The relative concentrations were determined by peak area (mm2). All peak detections were manually checked for false-positive and false-negative assignments. These mass spectra were then compared with known and commercially available mass spectral libraries. Statistical analysis was performed using pairwise comparison to determine significant differences. Metabolites that showed significant differences were grouped into functional categories.

Real-time quantitative TaqMan PCR systems

For each target gene, PCR primers and a TaqMan® probe were designed using Primer Express (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The total RNA fraction was incubated with RNase-free DNase I following protocol instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Absence of genomic DNA contamination was confirmed with a universal 18S TaqMan PCR system. cDNA was synthesized with 50 U of SuperScript III following protocol instructions (Invitrogen). Each PCR contained 20× Assay-on-Demand primer, probes for the respective TaqMan system, and TaqMan Universal PCR Mastermix (Applied Biosystems) and was amplified in an automated fluorometer (ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System, Applied Biosystems). Applied Biosystems standard amplification conditions were used: 2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, and 60 s at 60 °C. Fluorescent signals were collected during the annealing temperature and CT values extracted with a threshold of 0.04 and baseline values of 3–10. Three common housekeeping genes were examined: plant 18S rRNA (ssrRNA), apple glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and apple ribosomal protein S19. 18S rRNA had the lowest standard deviation across all tissues and its 18S rRNA CT values were therefore used to normalize the target gene CT values.

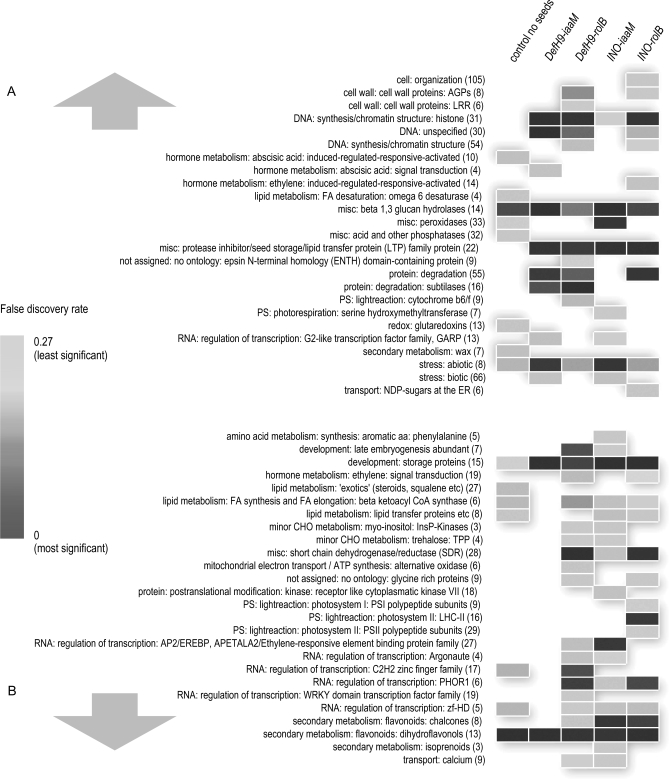

Statistical analysis of microarray data

Statistical analyses of microarray data were performed using R statistical software. The RMA method (Irizarry et al., 2003) was used for background subtraction and normalization to pre-process raw probe data and produce the gene expression matrix. To determine which genes were differentially expressed among different groups, one-way ANOVA was used to obtain a P-value for each gene. Then all P-values were BH adjusted (Benjamini and Hochberg, 2000) for multiple hypotheses. Genes with adjusted P-values <0.05 were considered differentially expressed in different groups. The R package LMGene (Rocke, 2004) was used to perform one-way ANOVA and the R package mulltest (Pollard et al., 2004) was used to adjust multiple hypotheses. Annotation of some sequences was supplied by Affymetrix Inc.; additional annotations were found by BLAST comparisons with the NCBI non-redundant protein and TAIR databases. Functional classifications were based on those in the MapMan software, a user-driven tool that displays large data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways or other processes. (Thimm et al., 2004). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to elucidate which functional categories of genes were more significantly associated with seeds and induced seedlessness. GSEA is a computational method that determines whether an a priori defined set of genes shows statistically significant, concordant differences between two biological states (Subramanian et al., 2005). Affymetrix tomato GeneChip targets matched Arabidopsis genes in >800 categories in the MapMan knowledge base. The 51 categories listed contained significant numbers of differentially expressed genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) <0.27. For each functional category a colour between blue (higher FDR, less significant) and red (lower FDR, more significant) and the number of genes differentially regulated were assigned.

PCA microarray and metabolomic analysis

Principal component analyses (PCA) was used to reduce the dimensionality of the microarray data (Fiehn et al., 2000). Arrays were considered as observations and genes as variables. PCA was also applied to the metabolomic data. There were 35 samples (one control and 6–8 replicates for each of the four transgenes) and measurements of 234 metabolites. Metabolites that were missing in >60% of the samples were ignored.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of transgenic plants

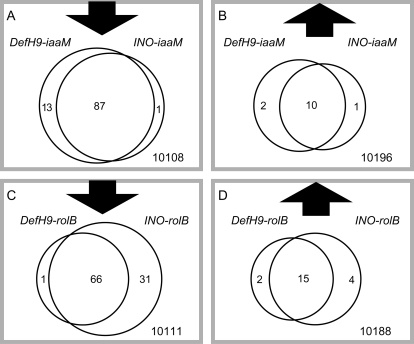

Parthenocarpy is a desirable trait in many commercially grown fruit crops if undesirable changes to quality, flavour, or nutrition can be avoided. This work is the first to demonstrate the ability of INO to induce parthenocarpy and a significant reduction in the number of seeds. The INO gene is required for ovule development in Arabidopsis and expression is limited to the predictive initiation site and developing outer (abaxial) cell layer of the ovule outer integument (Villanueva et al., 1999; Meister et al., 2004). There are several lines of indirect evidence that suggest INO expression is ovule specific in tomato. The tomato INO promoter was fused to the Arabidopsis INO and green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding regions (P-TOMINO::AtINO-GFP). Expression was observed in only one cell layer in the outer integument. This was fully consistent with in situ hybridizations that showed this same expression pattern for the endogenous tomato INO gene (Charles S Gasser, personal communication). Although a thicker pericarp was observed in some parthenocarpic fruits, there were no significant changes to radial pericarp thickness in the four different types of transgenic tomatoes compared with wild-type tissues. Finally, the strongest piece of evidence that INO expression in tomato is ovule specific is the comparison with the corresponding expression of DefH9. There was a strong overlap in the expression changes triggered by these two promoters, with only a very few specific genes being expressed exclusively in either INO or DefH9 transgenic plants (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pairwise comparison of each transgenic sample with control fruits without seeds. (A) and (B) the number of down-regulated and up-regulated genes (adjusted P-value <10−4) of samples from DefH9-iaaM and INO-iaaM lines. (C) and (D) Number of down-regulated and up-regulated genes (adjusted P-value <10−4) of samples from DefH9-rolB and INO-rolB lines. Much overlap exists between down-regulated and up-regulated genes in DefH9-iaaM and INO-iaaM samples. This is also the case in DefH9-rolB and INO-rolB samples.

Several transgenic plants were generated for each of the four possible promoter (INO or DefH9)–gene (iaaM or rolB) combinations and evaluated for seedlessness. For both promoters, ∼25–28% of transgenic tomato lines expressing iaaM lacked seeds; another 36–42% had only a few seeds (Table 1; Fig. 2). The remaining 33–36% had greatly diminished seed production. Of the transgenic plants expressing rolB, 20–33% lacked seeds, 40–45% had just a few seeds, and the remaining 22–40% had greatly diminished seed production (Table 1). INO and DefH9 have similar effects when controlling expression of iaaM or rolB and produce similar proportions of seedless and reduced-seed lines.

Table 1.

Number and type of transgenic plants obtained for each construct, with percentage and mean number of seeds/fruit

| INO-iaaM lines |

DefH9-iaaM lines |

INO-rolB lines |

DefH9-rolB lines |

|||||

| No. of lines | Seeds/fruit | No. of lines | Seeds/fruit | No. of lines | Seeds/fruit | No. of lines | Seeds/fruit | |

| All transgenic lines | 12 (100%) | 5.2 | 11 (100%) | 2.2 | 9 (100%) | 5.4 | 5 (100%) | 5.1 |

| Transgenic lines with fewer seeds | 5 (42%) | 0.9 a | 4 (36%) | 0.4 a | 4 (45%) | 1.3 a | 2 (40%) | 0.7 a |

| Transgenic lines without seeds | 3 (25%) | 0 a | 3 (28%) | 0 a | 3 (33%) | 0 a | 1 (20%) | 0 a |

| Transgenic lines with seeds | 4 (33%) | 10.4 b | 4 (36%) | 6.9 b | 2 (22%) | 14.6 b | 2 (40%) | 8.7 b |

| Control lines | 10 | 16.7 b | 10 | 16.7 c | 10 | 16.7 b | 10 | 16.7 b |

Significant differences were calculated using ANOVA univariate (P=0.0.5) among classes for each transgene and control (untransformed). Different letters for each different transgene indicate significant differences in comparison with control plants measured by Duncan multiple range test (P=0.05).

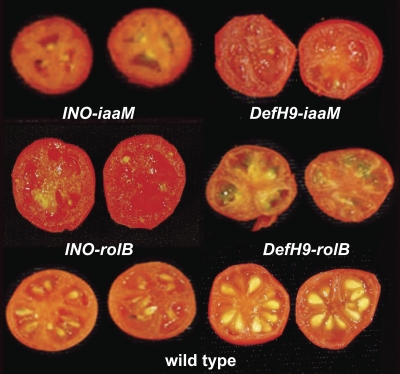

Fig. 2.

Wild-type and parthenocarpic transgenic tomato fruit generated with four different constructs (INO-iaaM, DefH9-iaaM, INO-rolB, and DefH9-rolB). No seeds are visible in the parthenocarpic lines.

Since several published works evaluated fruit quality and productivity of transgenic parthenocarpic fruits (Ficcadenti et al., 1999; Acciarri et al., 2002; Pandolfini et al., 2002; Rotino et al., 2005), the focus here was on fruit morphology and soluble solids content in order to measure differences between transgenic and wild-type fruits. MicroTom is a tomato cultivar suitable for analysis of fruit morphology but not fruit productivity. Only plants bearing completely parthenocarpic fruits were used for detailed transcriptome and metabolite analysis. Analysis was restricted to T0 plants as they produced very few seeds and the germination of these seeds was also low.

Fruit morphology

No significant morphological differences were observed among INO-iaaM and wild-type fruit (Table 2). Parthenocarpic fruits from plants transformed with DefH9-iaaM had reduced weight and equatorial diameter, but seeded and parthenocarpic INO-rolB fruits had increased polar and equatorial diameter. In DefH9-rolB plants, no clear relationship was observed between the presence of seeds and fruit diameter. No significant differences in soluble solids were found among wild-type and INO-iaaM, DefH9-iaaM, and INO-rolB fruits (Table 2), but DefH9-rolB transgenic tomatoes with few seeds/fruit had more soluble solids than control fruit. There were no significant differences among lines in the number of locules in individual fruits. Although differences were observed in diameters and weight between transgenic and wild-type fruits, no clear correlation between number of seeds, transgene, and fruit size was observed. Fruit growth is also controlled by the developing seeds, as parthenocarpic fruits are generally smaller than seeded fruits (Mapelli et al., 1978). The presence of seed-like structures that resemble pseudoembryos was observed. These were also found in auxin-induced fruit (Serrani et al., 2007), and originate from divisions of cells of the inner integument (Kataoka et al., 2003). These seed-like structures in transgenic tomato fruits were hypothesized to substitute for the seeds in stimulating fruit growth (Kataoka et al., 2003).

Table 2.

Phenotypes of wild-type and transgenic fruit produced on T0 plants

| Classes | Weight (g) | Polar diameter (mm) | Equatorial diameter (mm) | No. of locules | Brix value | |

| INO-iaaM | With few seeds | 2.1 | 15.5 | 13.0 | 2.7 | 9.0 |

| Without seeds | 2.1 | 13.1 | 13.9 | 3.0 | 9.8 | |

| With seeds | 2.0 | 13.0 | 13.9 | 2.6 | 7.7 | |

| Control | All lines | 1.8 | 12.2 | 13.2 | 2.4 | 8.2 |

| DefH9-iaaM | With few seeds | 2.2 b | 13.7 b | 15.0 c | 2.7 | 9.3 |

| Without seeds | 1.1 a | 11.0 a | 10.6 a | 2.7 | 8.3 | |

| With seeds | 2.0 b | 12.9 b | 12.5 b | 2.4 | 10.0 | |

| Control | All lines | 1.8 b | 12.2 a,b | 13.2 b | 2.4 | 8.2 |

| INO-rolB | With few seeds | 1.6 | 14.7 b | 14.0 a,b | 2.5 | 8.9 |

| Without seeds | 2.1 | 15.5 b | 15.8 c | 2.2 | 10.1 | |

| With seeds | 1.8 | 16.4 c | 15.0 b,c | 2.2 | 8.6 | |

| Control | All lines | 1.8 | 12.2 a | 13.2 a | 2.4 | 8.2 |

| DefH9-rolB | With few seeds | 1.8 a | 14.5 a,b | 14.7 a,b | 2.6 | 11.5 c |

| Without seeds | 1.8 a | 16.5 b | 15.2 a,b | 2.5 | 8.0 b | |

| With seeds | 2.5 a | 17.0 b | 16.7 c | 2.6 | 6.9 a | |

| Control | All lines | 1.8 a | 12.2 a | 13.2 a | 2.4 | 8.2 a,b |

Weight, polar and equatorial diameter, number of locules, and soluble solids were analysed by one-way ANOVA (P=0.05). Different letters in the same column indicate different groups by the Duncan multiple range test. No letters in the same column means no significative differences between classes.

Carmi et al. (2003) found a positive correlation between rolB and soluble solids, which was directly affected by seedlessness. Tomatoes transformed with DefH9-iaaM had increased soluble solids, probably because seedless fruits re-allocate assimilates from the seeds to the pericarp (Ficcadenti et al., 1999). Seedless fruit are more desirable than seeded: they are less acidic (Lukyanenko, 1991) and have more soluble solids (Falavigna et al., 1978) than seeded cultivars. DefH9-rolB lines with few seeds in the present study had increased soluble solids, but no significant changes were observed in the other transgenic lines.

Gene expression changes in transgenic and control tomato fruit

It is possible that the presence/absence of seeds could have significant effects on the surrounding carpel tissue. The Affymetrix tomato GeneChip was used to compare gene expression profiles of wild-type and transgenic fruits at the breaker stage and identify changes directly induced by transgene expression. At this stage, the formerly green MicroTom fruit had turned yellow, but not red. Although direct changes induced by genetic transformation in both the transcriptome and metabolome are likely to occur at earlier stages of development, it was expected to see long-term effects at the breaker stage, where the fruit has a clear and distinct phenotype that allows physiologically similar fruits to be compared. At this very active physiological stage, many gene expression changes occur, emphasizing differences among transgenic and wild-type untransformed fruits.

Using one-way ANOVA and multiple hypothesis testing, 1748 of 10 209 genes (17%) with significant variation (P <0.05) were identified among wild-type and transgenic fruits. Thus, 83% of the genes analysed showed no significant differences in expression due to parthenocarpy.

Pairwise comparison (one-way ANOVA, P <0.001) of the most differentially expressed genes showed 98 and 101 down-regulated genes (0.96% and 0.98% of all genes represented on the microarray), respectively, for rolB- and iaaM-transformed plants. There were also 13 and 21 up-regulated genes (0.13% and 0.21% of represented genes), respectively, for iaaM- and rolB-transformed plants (Fig. 3). Thus, only a small proportion of genes were regulated differently in all transgenic fruits than in wild-type fruits with seeds removed, and fewer genes were up-regulated than were down-regulated. Among promoters controlling the same transgene, there was much overlap between down-regulated and up-regulated genes in DefH9- and INO-transformed plants, suggesting very similar effects of the two promoters on gene expression. This evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that the A. thaliana INO promoter drives ovule-specific expression in tomato.

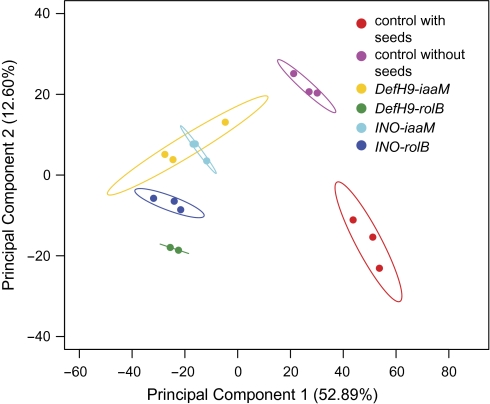

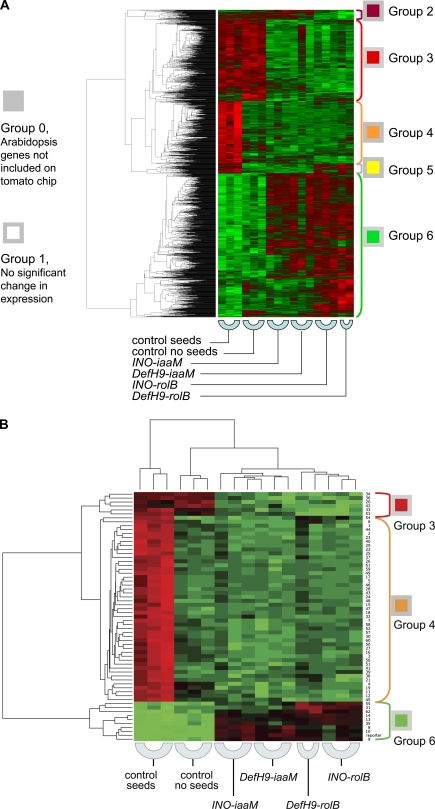

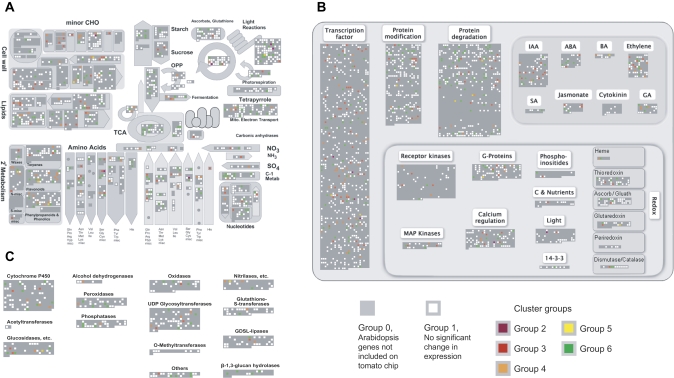

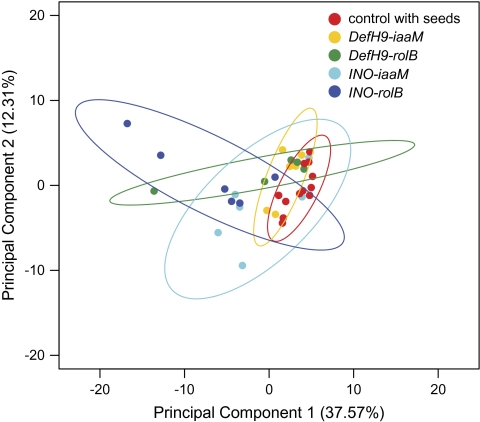

PCA was applied to 1748 genes with significant differences in expression (Fig. 4). Principal component 1, accounting for 53% of the variance, was probably the result of genes affected by the transgene's ovule-specific expression or by the absence of seeds. Principal component 2, accounting for 12.6% of the variance, represents gene expression modifications induced in different ways by iaaM and rolB ovule-specific expression, which act by different molecular mechanisms. iaaM encodes a tryptophan monoxidase producing indolacetamide, which is converted either chemically or enzymatically to indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (Inze et al., 1984). RolB is a putative tyrosine phosphatase operating in auxin signalling (Carmi et al., 2003). Despite extensive research, the actual function of the product of the rolB gene is still not clearly understood. Cluster analysis of individual genes confirmed the induction of six different gene expression patterns in transgenic lines (Fig. 5A). Genes in group 6 were up-regulated in at least one transgenic line compared with seeded or seedless wild-type fruits. These genes do not have seed-specific expression, but are involved in pathways affected by the ovule-specific expression of iaaM and rolB. Thus, they may play important roles in fruit quality and warrant further investigation. Functions of other genes up-regulated specifically in iaaM-transformed (group 2) or rolB-transformed fruits (group 5) may be of interest to better characterize gene expression differences induced by ovule-specific expression of these genes. The roles of genes down-regulated in parthenocarpic transgenic fruits (group 3) and those with seed-specific expression (group 4) may also be of interest. Functional analysis of the significantly differently regulated genes was performed using MapMan software (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Principal component analysis of 1748 genes with significant differences at P <0.05 in expression among transgenic and control fruits. The dots represent each of the 17 individual microarrays used in this study, and the ellipses represent the 95% confidence limit for the replicates in each group.

Fig. 5.

Cluster analysis of gene expression in control fruit with or without seeds and transgenic fruit with INO-iaaM, DefH9-iaaM, INO-rolB, or DefH9-rolB. Genes were clustered based on differential expression using the made4 package of R statistical software. Three biological replicates were used for each genotype, except for DefH9-iaaM, from which only two biological replicates were available. (A) Expression data for 1748 (18%) target genes with P <0.05 could be divided into five groups based upon expression patterns. (B) Hierarchical clustering and heat map for 62 (0.6%) target genes with P <10−4. Three of the five groups appeared in the latter.

Fig. 6.

Functional categorization of the six expression pattern groupings obtained from pairwise comparison of each transgenic sample with control fruits without seeds. MapMan display of pathway assignments for gene groups created in previous cluster analysis: (A) Metabolism overview, (B) Regulation overview, (C) Large enzyme families. Colours in small squares were assigned based on positions of target genes in the cluster analysis, indicated on the right margin of heat map figures. White squares indicate target genes whose expression did not pass the P <0.05 cut-off.

GSEA was very useful for showing the most important changes taking place in seedless transgenic fruits (Fig. 7). Among the 1748 differentially regulated genes, those that followed a similar pattern in GSEA analysis and had similar functions were strongly supposed to be affected by the absence of seeds. Interestingly, one effect of the transgene modification was the up-regulation of lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) in all four different transgenic fruit types compared with wild-type fruits with seeds removed. LTPs and puroindolines can inhibit the growth of fungal pathogens in vitro and they are capable of synergistically enhancing the antimicrobial properties of other antimicrobial peptides such as defensins and thionins (Marion et al., 2004). LTPs are also involved in the signalling of the defence mechanism of plants against their pathogens, recognizing membrane receptors involved in the transduction pathways of local defence responses (Blein et al., 2002). Although the accumulation of these proteins has to be confirmed, the up-regulation of the transcript is intriguing for the possibility to increase the resistance of plants to biotic stresses. In this regard, overexpression of these antimicrobial proteins induces significantly increased resistance of plants toward microbial pathogens (Marion et al., 2004). In addition, these antimicrobial proteins can help preserve fruit products.

Fig. 7.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of microarray expression data. (A) Functional categories up-regulated in at least one of the transgenic constructs, compared to controls with seeds. (B) Functional categories down-regulated in at least one of the transgenic constructs, compared to control with seeds. Affymetrix tomato GeneChip targets matched Arabidopsis genes in >800 categories in the MapMan knowledge base. The 51 categories listed contained significant numbers of differentially expressed genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) of <0.27. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of genes in each set.

The two analyses (GSEA and MapMan) were complementary and showed important similarities, providing a clearer picture of which gene categories were more affected by transgenic induction of parthenocarpy. The important conclusions of both analyses are outlined (Table 3). Interestingly, iaaM-transformed fruits up-regulated genes involved in abiotic stress and three of the four types of transgenic fruits up-regulated genes involved in protein degradation. These effects are also important topics of further investigations. Among the down-regulated genes, short chain dehydrogenase genes and PHOR1 transcription factors were associated with rolB. Transgenic potato plants expressing an antisense PHOR1 construct had a semi-dwarf phenotype, displayed reduced response to GA application, and had more endogenous GAs than control plants (Amador et al., 2001), supporting the hypothesis that PHOR1 is a positive regulator of GA signalling (Thomas and Sun, 2004).

Table 3.

Main gene expression changes between transgenic and seedless and seeded wild-type fruits, subdivided into functional categories

| Gene set enrichment analysis | MapMan analysis |

| Up-regulated | |

| DNA synthesis | |

| More up-regulation in DefH9 and INO-rolB fruits | Several genes involved in nucleotide synthesis were shown to be up-regulated (green colour, Fig. 5A) |

| Protein degradation | |

| Up-regulated in DefH9-transformed fruits | Many genes were shown to be up-regulated in transgenic fruits (green colours, Fig. 5B) |

| Lipid metabolism | |

| More up-regulation in iaaM fruits but also in rolB fruits and wild-type seedless | Several genes were shown to be up-regulated in transgenic seedless fruits (green colours, Fig. 5A) |

| Protein modification | |

| Acid and other phosphates up-regulated in all transgenic fruits | More genes were shown to be up-regulated than down-regulated (three genes were up-regulated in transgenic fruits, green colour, Fig. 5C) |

| Cell wall | |

| Weak up-regulation rolB fruits (more up-regulation DefH9-rolB fruits) | Two genes up-regulated in rolB fruits (yellow colour, Fig. 5A) |

| Secondary metabolism: waxes | |

| More up-regulation in iaaM fruits but also up-regulation in rolB fruits | Four genes analysed: one up-regulated and one down-regulated in transgenic seedless fruits. |

| Down-regulated | |

| Light reaction | |

| Genes were down-regulated in rolB fruits | Two genes were down-regulated in rolB fruits (cytocrome P450, orange colour, Fig. 5C) |

| Transcription factors | |

| Down-regulation of several RNA regulation factors in rolB fruits | Four genes down-regulated in rolB fruits, many others down-regulated in all transgenic seedless fruits |

| Secondary metabolism (flavanoid) | |

| Down-regulated in all transgenic and wild-type seedless fruits (seed-specific expression) | Many genes down-regulated in all seedless fruits (orange colour, Fig. 5A) |

| Ox/redox reaction | |

| Down-regulation in rolB fruits | A gene involved in oxidase down-regulated in rolB fruits |

| Storage proteins | |

| Down-regulation in all seedless fruits: above all the transgenic ones | Several genes involved in lipid and protein metabolism were down-regulated in seedless fruits |

A comparison between two different methods was performed: gene set enrichment analysis and MapMan functional categorization analysis. These gene expression changes are strongly supposed to be linked to parthenocarpy induced by mechanical or genetically engineered removal.

Another specific analysis of individual genes was performed by determining NCBI accession annotations of the 62 most differentially regulated genes with adjusted P-values <10−4 (ANOVA model) and clustering them into 19 functional categories (Table 4). Among down-regulated genes, the functional categories most affected by gene expression changes were those involved in light reactions, transcription factors, and redox reactions (rolB fruits), and flavonoid metabolism and storage proteins (all seedless fruits).

Table 4.

Predicted functions of 62 highly differentially regulated genes with adjusted P <10−4 in ANOVA model, belonging to clusters (Fig. 5) indicated in the third column

| MapMan categorization, from tblastx versus TAIR | Cluster | NCBI accession | Annotation | |

| 1 | Fermentation.aldehyde dehydrogenase | 4 | AW032379 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH1a) |

| 2 | Gluconeogenesis/glyoxylate cycle.malate synthase | 4 | AW649829 | Strong similarity to glyoxysomal malate synthase from Brassica napus |

| 3 | Mitochondrial electron transport | 4 | AI898816 | Alternative oxidase 2, mitochondrial (AOX2) |

| 4 | Metal handling | 4 | BT013123 | Selenium-binding family protein |

| 5 | 4 | BI203983 | Similar to ferric-chelate reductase (FRO1) (Pisum sativum) | |

| 6 | Redox.haem | 4 | AY026344 | Non-symbiotic haemoglobin |

| 7 | DNA synthesis/chromatin structure | 4 | BE462343 | High-mobility-group protein/HMG-I/Y protein |

| 8 | 6 | BT013634 | Minichromosome maintenance family protein | |

| 9 | 6 | BG626714 | Prolifera protein (PRL)/DNA replication licensing factor Mcm7 (MCM7) | |

| 10 | 6 | BT014477 | ATRPA2;ROR1;replicon protein A;suppressor of ROS1 | |

| 11 | 4 | BG123861 | AT-rich element -binding factor 3 [Pisum sativum] | |

| 12 | 4 | BT013761 | MAR-binding protein [Nicotiana tabacum] | |

| 13 | Protein degradation | 6 | BI931445 | Peptidase M20/M25/M40 family protein, similar to acetylornithine deacetylase |

| 14 | 6 | BI935106 | Acetylornithine deacetylase, putative [Brassica oleracea] | |

| 15 | 4 | AI898251 | Ubiquitin-protein ligase/zinc ion binding [Arabidopsis thaliana] | |

| 16 | Signalling | 4 | BT012984 | Contains eukaryotic protein kinase domain |

| 17 | 4 | AA824763 | Contains IQ calmodulin-binding motif, Pfam:PF00612 | |

| 18 | Transport/transporter | 4 | BG126449 | Cation exchanger, putative (CAX3), similar to high affinity calcium antiporter CAX1 |

| 19 | 4 | AI780345 | Integral membrane protein, putative/sugar transporter family protein | |

| 20 | 3 | BE458971 | Sugar transporter, putative, similar to ERD6 protein, Arabidopsis thaliana | |

| 21 | 4 | BT012913 | Putative nitrate transporter NRT1-3 [Glycine max] | |

| 22 | Miscellaneous | 4 | AW934450 | SSXT protein-related/glycine-rich protein |

| 23 | 4 | AF143742 | CBS domain-containing protein | |

| 24 | 4 | CK714819 | Hydrolase, alpha/beta fold family protein | |

| 25 | 4 | BI921484 | Transducin family protein/WD-40 repeat family protein | |

| 26 | 4 | AI773541 | Contains integral membrane protein domain, Pfam:PF01988 | |

| 27 | 4 | AI781043 | Low similarity to SP:P30043 flavin reductase {Homo sapiens} | |

| 28 | 4 | BG131258 | Cytochrome P450 71B23, putative (CYP71B23) | |

| 29 | 4 | BI928574 | GDSL-motif lipase/hydrolase family protein, similar to family II lipase EXL3 | |

| 30 | 4 | BG734983 | Putative zinc-binding domain (DUF701) | |

| 31 | 6 | CN385216 | Metallocarboxypeptidase inhibitor [Solanum tuberosum] | |

| 32 | Cell wall | 4 | BT014503 | GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase (GMP1) |

| 33 | 3 | AF154420 | Beta-galactosidase, putative/lactase | |

| 34 | Lipid metabolism | 3 | BT014559 | Long-chain acyl-CoA ligase/synthetase family protein |

| 35 | 6 | CK715596 | Phospholipase/carboxylesterase family protein | |

| 36 | Amino acid metabolism | 3 | BT013418 | Proline oxidase, putative/osmotic stress-responsive proline dehydrogenase |

| 37 | Secondary metabolism | 4 | AI486965 | Tropinone reductase/dehydrogenase, putative |

| 38 | 4 | BM535633 | Chalcone–flavanone isomerase family protein | |

| 39 | 4 | BG129167 | Undecaprenyl-phosphate alpha-N-acetylglucosaminyl 1-phosphate transferase | |

| 40 | 4 | BG631118 | Undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase [Leptospirillum sp. Group II UBA] | |

| 41 | Hormone metabolism | 4 | BG791226 | Cell elongation protein/DWARF1/DIMINUTO (DIM) |

| 42 | 3 | AY192367 | ERF (ethylene response factor) subfamily B-3 ERF/AP2 transcription factor | |

| 43 | 4 | AF454634 | Allene oxide synthase/hydroperoxide dehydrase/cytochrome P450 74A | |

| 44 | RNA.regulation of transcription | 4 | BG125438 | Basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) family protein |

| 45 | 4 | AI780243 | Zinc finger (C2H2 type) family protein | |

| 46 | 4 | AW031142 | MYB60;myb family transcription factor | |

| 47 | 4 | AW934591 | Zinc finger homeobox family protein | |

| 48 | 4 | BM412250 | Rcd1-like cell differentiation protein, putative | |

| 49 | Minor CHO metabolism | 4 | AW650462 | Trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase, putative |

| 50 | 4 | CN384702 | Inositol polyphosphate 6-/3-/5-kinase 2a (IPK2a) | |

| 51 | 4 | AI897093 | Inositol polyphosphate 6-/3-/5-kinase 2b (IPK2b) | |

| 52 | 4 | BG627650 | Inositol-3-phosphate synthase isozyme 2 | |

| 53 | 3 | AW933452 | PfkB-type carbohydrate kinase family protein | |

| 54 | Drought/salt stress response | 4 | AF500011 | Dehydration responsive element-binding protein, Lycopersicon esculentum |

| 55 | Unknown function | 6 | BT012940 | Unknown protein [Arabidopsis thaliana] |

| 56 | 4 | BT013091 | Hypothetical protein OsI_007083, Oryza sativa | |

| 57 | 4 | AW442644 | Contains similarity to cotton fibre expressed protein 1 | |

| 58 | 4 | BG629826 | NSH | |

| 59 | 4 | AW092459 | Os07g0631100, Oryza sativa | |

| 60 | 4 | BG628576 | Allantoin transporter [Arabidopsis thaliana] | |

| 61 | 4 | AW650005 | Harpin-induced 1 [Medicago truncatula] | |

| 62 | 6 | BG630221 | NSH |

Predicted functions are based on tblastx to TAIR and NCBI nr databases (NSH, no significant hit, at 10−5 expectation value threshold). Functional categories assigned by MapMan knowledge base. Numbers in the first column correspond to those near the right-hand margin of Fig. 5B.

Excluding genes with unknown function, these genes clustered primarily into the minor CHO metabolism, DNA synthesis, and transcription factor categories. In addition, several differentially regulated genes were involved in secondary metabolism and hormone metabolism. Another interesting category, transport/transporters, was represented by four differentially regulated genes: a cation exchanger, two sugar transporters, and nitrate transporter NRT1-3.

Hormone metabolism genes such as those encoding Dwf1 (Dwarf1/Diminuito), ERF/AP2 transcription factor, and allene oxide synthase (AOS) were differentially regulated between transgenic and wild-type fruits. Interestingly, transgenic plants that overexpress dwarf4 in the brassinosteroid biosynthesis pathway showed increased vegetative growth and seed yield, consistent with the result found here that a putative dwarf4 gene was highly down-regulated in transgenic seedless fruits. Although some transgenic tomatoes showed lower internodes, no clear correlation was observed between seedlessness and reduction of vegetative growth. MicroTom plants are naturally bushy and short, however, so any possible effect of rolB and iaaM ovule-specific expression on brassinosteroid biosynthetic genes and vegetative growth must be investigated in other tomato cultivars.

Interestingly, the functional characterization showed that several ethylene- and IAA- associated genes were also down-regulated in transgenic parthenocarpic fruits (Fig. 6, group 3), while others were up-regulated (group 6). Possible interactions between auxin and ethylene metabolism and perception are also of interest. EREBPs are both transcriptional activators and repressors in plants (Fujimoto et al., 2000), and constitute a large gene family in tomato with important consequences for fruit softening and shelf life. Since some EREBPs induce ripening and others are repressed, Fei et al. (2004) proposed a model in which EREBPs dynamically regulate fruit ripening using antagonistic mechanisms.

Among the IAA-responsive genes, down-regulation of an auxin-regulated protein (BT013913.1) in transgenic parthenocarpic fruits was confirmed using real-time RT-PCR. This evidence agrees with previously published data that showed down-regulation of IAA-responsive genes associated with parthenocarpy such as the silencing of an auxin-responsive factor (SlARF7) (de Jong et al., 2009). Mutations in Arabidopsis ARF8, also referred to as Fruit Without Fertilization (FWF), cause fruit set in the absence of pollination and fertilization (Goetz et al., 2007). Parthenocarpic fruits have been obtained through down-regulation of IAA9, a tomato Aux/IAA family member (Wang et al., 2005). Recently it has been shown that auxins induce fruit set and growth in tomato, partially enhancing GA biosynthesis and decreasing GA inactivation, leading to more GA1 as observed in parthenocarpic fruits induced by 2,4-D. These conclusions were made after observation of more transcript for genes encoding copalyldiphosphate synthase (SlCPS), SlGA20ox1, SlGA20ox2, SlGA20ox3, and SlGA3ox1 in unpollinated ovaries treated with 2,4-D than in unpollinated untreated ovaries (Serrani et al., 2008).

Seedless fruit often has a longer shelf life than seeded fruit because seeds produce hormones such as ethylene that trigger senescence (Fei et al., 2004). Interestingly, the present data showed that IAA-responsive genes were down-regulated in all transgenic fruits compared with seedless or seeded wild-type fruits, implying that the ovule- and ovary- driven expression of IAA and rolB induces down-regulation of other auxin-associated genes irrespective of seeds. It is possible that these negative regulators induce parthenocarpy as in the down-regulation of SlARF7 ovary transcript after pollination in tomato (de Jong et al., 2009).

A gene encoding an AOS in the jasmonate biosynthesis pathway was highly down-regulated in seedless transgenic fruits. Since published data associate jasmonates with early stages in climacteric fruit ripening and triggering ethylene production (Janoudi and Flore, 2003), it is of interest to determine whether seedless transgenic fruits differ in the rate of fruit ripening or in shelf life.

Among genes with differential expression in transgenic fruit, some highly down-regulated genes may have important functions in fruit development. Fifteen down-regulated genes were found in parthenocarpic transgenic fruits that were involved in cell wall metabolism (Fig. 6). Two of these, GDP-mannose pyrophorylase (GMP1) and β-galactosidase, were highly down-regulated, and a β-1,3 glucan hydrolase was significantly up-regulated in seedless fruits. The effect of these expression changes merits further investigation, since in tomato many genes may cause fruit softening (Giovannoni et al., 1989). Indeed, additional cell wall hydrolases and expansins have been associated with tomato fruit softening (Smith and Gross, 2000).

Another important functional category among differentially expressed genes was minor CHO metabolism involved in fruit sugar partitioning. The metabolomic analysis found no differences in sugars, but this was not verified in ripe fruit. Many proteins in these pathways are allosterically regulated, so their activity in the fruit may be less affected by changes in transcript level.

To validate these data with TaqMan real-time PCR analysis, 17 genes were analysed for correspondence between microarrays and real-time PCR (Table 5A, B). Twelve of the 17 genes showed a microarray versus real-time RT-PCR correlation of >0.75 and the remaining five genes showed a lower correlation. These five genes were the high affinity calcium antiporter CAX1 (BG126449), sugar transporter (BE458971), L-lactate dehydrogenase (BT013913.1), short-chain dehydrogenase reductase (BT014398.1), and putative vicilin (BT013421.1) (Table 5C). However, genes involved in auxin and ethylene biosynthesis and signalling were confirmed to be differentially regulated between transgenic and wild-type fruits.

Table 5.

Comparison of normalized intensity values from microarray experiments (A) and corresponding expression values from real time-PCR (B) for 17 genes showing significant expression changes between control and seedless types

| (A) | ||||||||

| Affymetrix Probe Set ID | Microarray data |

|||||||

| NCBI accession | Control no seeds | Control with seeds | INO-iaaM | DefH9-iaaM | INO-rolB | DefH9-rolB | ANOVA P-value | |

| Les.4140.1.S1_at | AY192367.1 | –0.1 | 3.2 | –4 | –3 | –7.3 | –4.4 | 0.000166 |

| LesAffx.23546.1.S1_at | BG126449 | 0.3 | –17.8 | –12.1 | –2.5 | –11.9 | –3.4 | 0.011324 |

| Les.5021.1.S1_at | BT013123.1 | –0.3 | 0.6 | –6 | –7.9 | –4.8 | –3.9 | 0.018553 |

| Les.3642.1.S1_at | U17972.1 | 0.3 | 1.8 | –5.5 | –19.2 | –5.9 | –3.2 | 0.005197 |

| LesAffx.56785.1.S1_at | BE458971 | 0.3 | 2.2 | –15.7 | –10.4 | –35.4 | –58.8 | 0.0207 |

| Les.2767.1.S1_at | U18678.1 | –0.3 | –6.5 | –45.9 | –59.8 | –57.5 | –18.6 | 0.002179 |

| Les.3492.1.S1_at | AY013256.1 | –0.3 | 1.9 | –7 | –6.5 | –10 | –9.3 | 0.000119 |

| Les.3122.2.A1_at | S66607.1 | –0.3 | –0.2 | 2252.2 | 3528 | 5033 | 3839.4 | 1.09E-06 |

| Les.2832.1.S1_at | CN384480 | 0 | 3.3 | 64.6 | 56.6 | 151.7 | 89.1 | 0.000174 |

| Les.3766.1.S1_at | U77719.1 | 0 | 2 | –16.9 | –12.6 | –2.3 | –7.6 | 0.006146 |

| LesAffx.70635.1.S1_at | BI421189 | –0.3 | 1.9 | –7 | –10.2 | –6 | –2.9 | 9.85E-06 |

| Les.97.1.S1_at | BT013913.1 | –0.3 | 3.1 | –4 | –15.5 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 0.049221 |

| Les.3486.1.S1_at | AF416289.1 | –0.2 | 1.5 | –5.9 | –5.9 | –2 | –1.5 | 2.89E-05 |

| LesAffx.58308.1.S1_at | BG129227 | –0.3 | 0.7 | –38 | –23.9 | –12.2 | –8.3 | 0.014537 |

| Les.3330.2.S1_at | BE458823 | 0 | 14.2 | 47.4 | 1193.1 | 2032 | 3304 | 0.000761 |

| Les.5694.1.S1_at | BT014398.1 | –0.3 | –5.6 | –27.5 | –109.8 | –82 | –18.7 | 0.003884 |

| Les.5168.1.S1_at | BT013421.1 | 0.2 | –17.1 | –136.9 | –201.3 | –337 | –332.4 | 0.013441 |

| Les.5024.1.S1_at | BT013126.1 | 0 | 13.6 | 100.9 | 336.6 | 1377.4 | 786.9 | 0.002116 |

| (B) | ||||||||

| Affymetrix Probe Set ID | Real time RT-PCR data |

Microarray versus real-time RT-PCR correlation | ||||||

| Control no seeds | Control with seeds | INO-iaaM | DefH9-iaaM | INO-rolB | DefH9-rolB | ANOVA P-value | ||

| Les.4140.1.S1_at | 6.5 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 3.78E-05 | 0.97 |

| LesAffx.23546.1.S1_at | 6.4 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 1.24E-07 | 0.63 |

| Les.5021.1.S1_at | 9.8 | 8.8 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 1.69E-05 | 0.87 |

| Les.3642.1.S1_at | 7.5 | 8 | 4 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 0.000117 | 0.56 |

| LesAffx.56785.1.S1_at | 6.1 | 6.6 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 5.18E-05 | 0.67 |

| Les.2767.1.S1_at | 12.3 | 9.9 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 7.8 | 0.000176 | 0.83 |

| Les.3492.1.S1_at | 9.2 | 9.6 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 8 | 8 | 0.000414 | 0.89 |

| Les.3122.2.A1_at | 6.1 | 6.6 | 7.3 | 8 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 0.000569 | 0.98 |

| Les.2832.1.S1_at | 6.9 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 0.001232 | 0.96 |

| Les.3766.1.S1_at | 11.5 | 12.2 | 8.1 | 9.1 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 0.0017 | 0.98 |

| LesAffx.70635.1.S1_at | 9.2 | 9.3 | 6.1 | 7 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 0.003298 | 0.85 |

| Les.97.1.S1_at | 6.9 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 0.003809 | 0.54 |

| Les.3486.1.S1_at | 10.8 | 10.7 | 8.3 | 9 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 0.003948 | 0.84 |

| LesAffx.58308.1.S1_at | 12 | 11.8 | 7.8 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 9 | 0.003929 | 0.8 |

| Les.3330.2.S1_at | 5.3 | 5.7 | 6 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 0.00633 | 0.94 |

| Les.5694.1.S1_at | 12.7 | 9 | 6 | 5.9 | 6.8 | 7.8 | 0.010221 | 0.68 |

| Les.5168.1.S1_at | 11.9 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 0.012949 | 0.58 |

| Les.5024.1.S1_at | 5.6 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 7 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 0.035691 | 0.76 |

| (C) | ||

| Affymetrix Probe Set ID | NCBI accession | Possible function, based on Blast analysis |

| Les.4140.1.S1_at | AY192367.1 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 1 |

| LesAffx.23546.1.S1_at | BG126449 | High affinity calcium antiporter CAX1 |

| Les.5021.1.S1_at | BT013123.1 | Selenium-binding family protein |

| Les.3642.1.S1_at | U17972.1 | ACC synthase |

| LesAffx.56785.1.S1_at | BE458971 | Sugar transporter |

| Les.2767.1.S1_at | U18678.1 | Isocitrate lyase |

| Les.3492.1.S1_at | AY013256.1 | Phospholipase PLDb2 |

| Les.3122.2.A1_at | S66607.1 | Pectinesterase-1 precursor |

| Les.2832.1.S1_at | CN384480 | Peroxidase precursor |

| Les.3766.1.S1_at | U77719.1 | Ethylene-responsive late embryogenesis-like protein |

| LesAffx.70635.1.S1_at | BI421189 | Wound-responsive AP2 like factor 1 |

| Les.97.1.S1_at | BT013913.1 | L-Lactate dehydrogenase |

| Les.3486.1.S1_at | AF416289.1 | Auxin-regulated protein |

| LesAffx.58308.1.S1_at | BG129227 | C-repeat-binding protein 4 |

| Les.3330.2.S1_at | BE458823 | Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein FLA2 |

| Les.5694.1.S1_at | BT014398.1 | Short-chain dehydrogenase reductase |

| Les.5168.1.S1_at | BT013421.1 | Putative vicilin |

| Les.5024.1.S1_at | BT013126.1 | MADS-box transcription factor FBP29 |

Correlation values comparing the overall expression pattern between the two experiments are given in the last column in (B). Functional descriptions for the 17 genes are given in (C). Genes that showed a microarray versus real-time RT-PCR correlation <0.75 are indicated in bold

Metabolomic analysis of transgenic and control fruit

The next sep was to address how the changes in gene expression altered the overall metabolomic profile of parthenocarpic transgenic fruit. The concentrations of >400 metabolites in parthenocarpic fruits transformed with the four different constructs were compared (in total six replicates for each construct except DefH9-rolB, from which only two different plants with five fruits were available) with those from 12 wild-type fruits containing seeds.

The acquired data sets were compared using PCA (Fiehn et al., 2000) to determine differences and similarities among transgenic seedless fruits and seeded wild-type fruits at the breaker stage. Linear combination of metabolic data generated new vectors or groups to best explain overall variance in the data set without prior assumptions about whether and how clusters might form. It was immediately clear that the overall metabolomic data did not show clear differences among the different fruit genotypes (Fig. 8). PCA could not separate the four transgenic lines and the controls: the 95% confidence intervals of the four treatments and two controls overlapped. Principal component 1, which accounted for ∼38% of the variance, partly distinguished the control from some parthenocarpic lines such that all negative values were from transgenic lines, but the separation was not complete. Principal component 2 did not clearly separate any treatments from the controls.

Fig. 8.

Principal component analysis of the relative abundance of significantly regulated metabolites obtained from a profile of 400 metabolites sampled for in control and transgenic tomato fruit. The dots represent the biological replicates of the different lines and ellipses define the 95% confidence limits of the metabolite data.

The relative concentrations of >400 metabolites were determined by peak area in transgenic and control fruits. However, many of them do not have a completely determined structure and could not be identified as a known molecule. Metabolites with known structure were divided into important functional categories (amino acids, sugars, fatty acids, other acids, and other compounds) and they were compared with transgenic seedless and wild-type seeded fruits using ANOVA univariate analysis (P=0.05). It was expected that most differences at a metabolomic level induced by the transgene expression might occur at the beginning of fruit set and before fruits reached their final size. However, some changes are also expected when fruits reach the breaker stage. This stage is physiologically very active, crucial for the ripening process, and important for the development of fruit quality phenotypes. Among 400 compounds analysed, only 16 showed significant differences between transgenic and wild-type fruits (Table 6). Three of 19 amino acids showed significant differences (serine, β-alanine, and asparagine). INO-rolB-transformed fruits had higher concentrations of these three amino acids than other seedless and seeded fruits. Six of the 18 acids determined revealed significant differences among different fruits. INO-rolB fruits had significantly more glutamate, malate, fumarate, and ascorbate than the other transgenic and seeded wild-type fruits. Among fatty acids, DefH9-iaaM and rolB-transformed fruits had significantly more stearic acid and palmitic acid than seeded wild-type fruits. Linoleic acid was also significantly higher in all transgenic fruits than in seeded wild-type fruits.

Table 6.

Relative amounts of metabolites with significant differences among seedless fruits transformed with four different constructs and seeded wild-type fruits

| Functional category | Seeded wild type | INO-iaaM | DefH9-iaaM | INO-rolB | DefH9-rolB |

| Amino acids | |||||

| Serine | 3930.6 a | 20 349.5 a,b | 37623.0 a | 54 467.5 c | 8959.2 a,b |

| β-Alanine | 488.0 a | 5006.8 a,b | 1555.7 a | 18 304.2 c | 6522.0 a,b |

| Asparagine | 9306.4 a | 33 263.3 a | 17 305.5 a | 107 133.7 b | 47 176.0 a,b |

| Glutamate | 9549.2a | 25 995.0 a | 13 940.0 a | 68 592.8 b | 18 695.6 a |

| Fatty acids | |||||

| Linoleic acid | 903.4 a | 1767.2 b | 2109.5 b | 2204.0 b | 2151.0 b |

| Palmitic acid | 6286.6 a | 12 087.7 a,b | 17 665.8 b | 17 531.5 b | 15 484.8 b |

| Stearic acid | 1959.9 a | 3123.2 a,b | 4200.3 b | 3872.5 b | 3672.6 b |

| Other acids | |||||

| Maleic acid | 11798.6 a | 195 041.2 a | 45 742.6 a | 402 413.6 b | 40 503.8 a |

| Fumaric acid | 684.7 a | 8142.4 a | 2517.7 a | 28 979.0 b | 2072.7 a |

| Aconitic acid | 472.7 a | 3031.4 a,b | 1245.0 a,b | 5884.3 b | 366.0 a |

| Succinic acid | 2164.8 a | 8746.5 b | 4019.8 a,b | 77 24.0 a,b | 3070.0 a,b |

| Ascorbic acid | 654.7 a | 976.2 a | 761.7 a | 3485.4 b | – |

| Other compounds | |||||

| Oxoproline | 11 833.7 a | 140 969.0 a,b | 64 641.5 a,b | 348 373.40 c | 195 140.0 b,c |

| Ethanolamine | 7212.0 a | 9499.4 a,b | 11 658.0 b | 15 232.67 c | 14 706.2 c |

| Putrescine | 9353.7 a | 57 317.5 a,b | 24 391.3 a,b | 70 000.17 c | 13 695.0 a |

| GABA | 125 835.2 a | 308 213.6 a,b | 105439.0 a | 453 237.00 b | 223 787.2 a |

Metabolites were divided in functional categories. Mean values are reported as peak area determined by a Pegasus III TOF mass spectrometer. Differences in letters for the same row for each metabolite indicated significant differences between treatments using ANOVA univariate (P=0.05).

Among other metabolites, rolB fruits had more oxoproline and ethanolamine and INO-rolB fruits had more putrescine than seeded wild-type fruits. There were no significant differences in sugars (sucrose, glucose, fructose, or sorbitol) among transgenic and wild-type fruits. Despite the differences in gene expression among transgenic and control fruit, PCA analysis of 400 metabolites showed that the overall metabolomic analysis did not distinguish transgenic fruit from untransformed controls (Fig. 8). Analysis was performed in fruits at a breaker stage and it would be interesting to determine what occurs also in the ripe fruits.

Since only 16 metabolites showed significant differences between transgenic and wild-type fruits, the fundamental metabolism of the fruit seemed to be mostly unchanged. However, some important metabolites were higher in parthenocarpic than in wild-type fruits, especially in INO-rolB fruits, which had the most variability among biological replicates. Although all fruits were harvested at the breaker stage, such biological variability was expected due to unavoidable small differences in fruit developmental stage. However, it is also possible that these metabolite differences were due to ovule-driven expression of rolB regulating rolB-specific fruit metabolic pathways.

Fatty acids were significantly higher in DefH9-iaaM and rolB-transformed fruits than in seeded wild-type fruits. Linoleic acid was also significantly higher in all transgenic fruits than in seeded wild-type ones. These data are coincident with differences observed in transcripts related to lipid metabolism. In Arabidopsis, auxins and cytokinins induce FAD3, a desaturase gene that alters fatty acid composition (Matsuda et al., 2001). Several genes involved in auxin metabolism were differentially regulated in our transgenic seedless fruits than in wild-type fruits: some were down-regulated and some up-regulated. Although Yamamoto (1994) reported that fatty acid desaturases are auxin regulated in mung bean, auxin regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis is not fully understood.

Conclusions

This study showed that the INO promoter from Arabidopsis fused with the iaaM or rolB gene effectively induced parthenocarpy in tomato. At both transcriptomic and metabolomic levels, changes were detected between transgenic parthenocarpic and wild-type fruits. Significant differences were observed in gene expression profiles and in several differentially regulated genes, such as those involved in the cell wall, hormone metabolism and response (auxin in particular), and metabolism of sugars and lipids. Interesting results such as the up-regulation of LTPs in transgenic seedless fruits open up the possibility of investigating their roles in response to biotic stresses. The down-regulation of several ethylene- and IAA- associated genes in transgenic parthenocarpic fruits is also intriguing for its possible effects on fruit shelf life and softening. Only 16 of 400 metabolites analysed at the breaker stage showed significant differences between transgenic and wild-type fruits. The overall metabolomic analysis performed at a breaker stage did not distinguish transgenic fruit from untransformed controls, implying that fruit metabolism remained essentially unchanged.

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al., 2002) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE14358 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE14358).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants obtained from the Citrus Research Board of California, by NSF grant IOB-0419531 to CSG, and by NIH Grant R01-HG003352 to DMR. The authors wish to thank Mary Lou Mendum for assistance in editing the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GA

gibberellic acid

- GSEA

gene set enrichment analysis

- INO

INNER NO OUTER

- LTP

lipid transfer protein

- PCA

principal component analysis

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PG

polygalacturonase

References

- Abad M, Monteiro AA. The use of auxins for the production of greenhouse tomatoes in mild-winter conditions—a review. Scientia Horticulturae. 1989;38:167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Acciarri N, Restaino F, Vitelli G, Perrone D, Zottini M, Pandolfini T, Spena A, Rotino GL. Genetically modified parthenocarpic eggplants: improved fruit productivity under both greenhouse and open field cultivation. BMC Biotechnology. 2002;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador V, Monte E, García-Martínez JL, Prat S. Gibberellins signal nuclear import of PHOR1, a photoperiod-responsive protein with homology to Drosophila armadillo. Cell. 2001;106:343–354. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. On the adaptive control of the false discovery fate in multiple testing with independent statistics. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2000;25:60–83. [Google Scholar]

- Blein JP, Coutos-Thévenot P, Marion D, Ponchet M. From elicitins to lipid transfer proteins: a new insight in cell signaling involved in plant defence mechanism. Trends in Plant Science. 2002;7:293–296. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmi N, Salts Y, Dedicova B, Shabtai S, Barg R. Induction of parthenocarpy in tomato via specific expression of the rolB gene in the ovary. Planta. 2003;215:726–735. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M, Wolters-Arts M, Feron R, Mariani C, Vriezen WH. The Solanum lycopersicum auxin response factor 7 (SlARF7) regulates auxin signaling during tomato fruit set and development. The Plant Journal. 2009;57:160–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donzella G, Spena A, Rotino GL. Transgenic parthenocarpic eggplants: superior germplasm for increased winter production. Molecular Breeding. 2000;6:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar MA, Civerolo EL, Summerfelt KR, Dandekar AM. RNAi-mediated oncogene silencing confers resistance to crown gall tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencies, USA. 2001;98:13437–13442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241276898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falavigna A, Badino M, Soressi GP. Potential of the monomendelian factor Pat in the tomato breeding for industry. Genetica Agraria. 1978;32:159–160. [Google Scholar]

- Fei ZJ, Tang X, Alba RM, White JA, Ronning CM, Martin GB, Tanksley SD, Giovannoni JJ. Comprehensive EST analysis of tomato and comparative genomics of fruit ripening. The Plant Journal. 2004;40:47–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficcadenti N, Sestili S, Pandolfini T, Cirillo C, Rotino GL, Spena A. Genetic engineering of parthenocarpic fruit development in tomato. Molecular Breeding. 1999;5:463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Fiehn O, Kopka J, Dormann P, Altmann T, Trethewey RN, Willmitzer L. Metabolite profiling for plant functional genomics. Nature Biotechnology. 2000;18:1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/81137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillati JJ, Kiser J, Rose R, Luca C. Efficient transfer of a glyphosate tolerance gene into tomato using a binary Agrobacterium tumefaciens vector. Biotechnology. 1987;5:726–730. [Google Scholar]

- Fos M, Proano K, Nuez F, Garcia-Martinez JL. Role of gibberellins in parthenocarpic fruit development induced by the genetic system pat-3/pat-4 in tomato. Physiologia Plantarum. 2001;111:545–550. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2001.1110416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto SY, Ohta M, Usui A, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:393–404. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillapsy G, Be-David H, Gruissem W. Fruits: a developmental perspective. The Plant Cell. 1993;5:1439–1451. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.10.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni JJ, Dellapenna D, Bennett AB, Fischer RL. Expression of a chimeric polygalacturonase gene in transgenic rin (ripening inhibitor) tomato fruit results in polyuronide degradation but not fruit softening. The Plant Cell. 1989;1:53–63. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz M, Hooper LC, Johnson SD, Rodrigues JCM, Vivian-Smith A, Koltunow AM. Expression of aberrant forms of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 stimulates parthenocarpy in Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant Physiology. 2007;145:351–366. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.104174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inze D, Follin A, Vanlijsebettens M, Simoens C, Genetello C, Vanmontagu M, Schell J. Genetic-analysis of the individual T-DNA of a Agrobacterium tumefaciens—further evidence that 2 genes are involved in indole-3-acetic-acid synthesis. Molecular and General Genetics. 1984;194:265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoudi A, Flore JA. Effects of multiple applications of methyl jasmonate on fruit ripening, leaf gas exchange and vegetative growth in fruit trees. Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology. 2003;78:793–797. [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka K, Uemachi A, Yazawa S. Fruit growth and pseudoembryo development affected by uniconazole, an inhibitor of gibberellin biosynthesis, in pat-2 and auxin-induced parthenocarpic tomato fruits. Scientia Horticulturae. 2003;98:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lukyanenko AN. Parthenocarpy in tomato. In: Kaloo G, editor. Genetic improvement of tomato. Monographs on theoretical and applied genetics. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Mapelli S, Frova C, Torti G, Soressi GP. Relationship between set, development and activities of growth regulators in tomato fruits. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1978;19:1281–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Marion D, Douliez JP, Gautier MF, Elmorjani K. Plant lipid transfer proteins: relationships between allergenicity and structural, biological and technological properties. In: Mills ENC, Shewry PR, editors. Plant food allergens. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2004. pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda O, Watanabe C, Iba K. Hormonal regulation of tissue-specific ectopic expression of an Arabidopsis endoplasmic reticulum-type omega-3-fatty acid desaturase (FAD3) gene. Planta. 2001;213:833–840. doi: 10.1007/s004250100575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister RJ, Williams LA, Monfared MM, Gallagher TL, Kraft EA, Nelson CG, Gasser CS. Definition and interactions of a positive regulatory element of the Arabidopsis INNER NO OUTER promoter. The Plant Journal. 2004;37:426–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfini T, Rotino GL, Camerini S, Defez R, Spena A. Optimisation of transgene action at the post-transcriptional level: high quality parthenocarpic fruits in industrial tomatoes. BMC Biotechnology. 2002;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard KS, Dudoit S, van der Laan MJ. Multiple testing procedures: R multtest package and applications to genomics. In: Gentleman R, Carey VJ, Huber W, Irizarry R, Dudoit S, editors. Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and Bioconductor. Berlin: Springer; 2004. pp. 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Rocke DM. Design and analysis of experiments with high throughput biological assay data. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2004;15:703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotino GL, Acciarri N, Sabatini E, et al. Open field trial of genetically modified parthenocarpic tomato: seedlessness and fruit quality. BMC Biotechnology. 2005;5:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotino GL, Perri E, Zottini M, Sommer H, Spena A. Genetic engineering of parthenocarpic plants. Nature Biotechnology. 1997;15:1398–1401. doi: 10.1038/nbt1297-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotino GL, Sommer H, Saedler H, Spena A. Methods for producing parthenocarpic or female sterile transgenic plants and methods for enhancing fruit setting and development. 1996 EPO patent No. EPO 961206455. [Google Scholar]

- Serrani JC, Fos M, Atares A, Garcia-Martinez JL. Effect of gibberellin and auxin on parthenocarpic fruit growth induction in the cv MicroTom of tomato. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 2007;26:211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Serrani JC, Ruiz-Rivero O, Fos M, Garcia-Martinez JL. Auxin-induced fruit-set in tomato is mediated in part by gibberellins. The Plant Journal. 2008;56:922–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slightom JL, Durand-Tardif M, Jouanin L, Tepfer D. Nucleotide sequence analysis of TL-DNA of Agrobacterium rhizogenes agropine type plasmid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:108–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DL, Gross KC. A family of at least seven betagalactosidase genes is expressed during tomato fruit development. Plant Physiology. 2000;123:1173–1183. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spena A, Saedler H, Sommer H, Rotino GL. Methods for producing parthenocarpic or female sterile transgenic plants and methods for enhancing fruit setting and development. 2002 US Patent 6483012. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimm O, Blasing O, Gibon Y, Nagel A, Meyer S, Kruger P, Selbig J, Muller LA, Rhee SY, Stitt M. MAPMAN: a user-driven tool to display genomics data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. The Plant Journal. 2004;37:914–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2004.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SG, Sun TP. Update on gibberellin signaling. A tale of the tall and the short. Plant Physiology. 2004;135:668–676. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoquaux F, Blanvillain R, Delseny M, Gallois P. Less is better: new approaches for seedless fruit production. Trends in Biotechnology. 2000;18:233–242. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(00)01448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva JM, Broadhvest J, Hauser BA, Mesiter RJ, Schneitz K, Gasser CS. INNER NO OUTER regulates abaxial–adaxial patterning in Arabidopsis ovules. Genes and Development. 1999;13:3160–3169. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.23.3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan C, Wilkins TA. A modified hot borate method significantly enhances the yield of high-quality RNA from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Analytical Biochemistry. 1994;223:1–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Jones B, Li ZG, Frasse P, Delalande C, Regad F, Chaabouni S, Latche A, Pech JC, Bouzaven M. The tomato Aux/IAA transcription factor IAA9 is involved in fruit development and leaf morphogenesis. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:2676–2692. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen-jun S, Forde BG. Efficient transformation of Agrobacterium spp. by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Research. 1989;17:8385. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.20.8385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto KT. Further characterization of auxin-regulated messenger-RNAs in hypocotyls sections of mung bean (Vigna radiate (L) Wilczek)—sequence homology to genes for fatty-acid desaturase and atypical late-embryogenesis-abundant protein, and the mode of expression of the messenger-RNAs. Planta. 1994;192:359–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00198571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]