Abstract

Background: Job stress has been associated with poor outcomes. In focus groups and small-sample surveys, physical therapists have reported high levels of job stress. Studies of job stress in physical therapy with larger samples are needed.

Objective: The purposes of this study were: (1) to determine the levels of psychological job demands and job control reported by physical therapists in a national sample, (2) to compare those levels with national norms, and (3) to determine whether high demands, low control, or a combination of both (job strain) increases the risk for turnover or work-related pain.

Design: This was a prospective cohort study with a 1-year follow-up period.

Methods: Participants were randomly selected members of the American Physical Therapy Association (n=882). Exposure assessments included the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ), a commonly used instrument for evaluation of the psychosocial work environment. Outcomes included job turnover and work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

Results: Compared with national averages, the physical therapists reported moderate job demands and high levels of job control. About 16% of the therapists reported changing jobs during follow-up. Risk factors for turnover included high job demands, low job control, job strain, female sex, and younger age. More than one half of the therapists reported work-related pain. Risk factors for work-related pain included low job control and job strain.

Limitations: The JCQ measures only limited dimensions of the psychosocial work environment. All data were self-reported and subject to associated bias.

Conclusions: Physical therapists’ views of their work environments were positive, including moderate levels of demands and high levels of control. Those therapists with high levels of demands and low levels of control, however, were at increased risk for both turnover and work-related pain. Physical therapists should consider the psychosocial work environment, along with other factors, when choosing a job.

Job stress increases the risk for a variety of adverse outcomes. These outcomes include burnout,1,2 turnover,3 sickness absence,4 and work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs).5 Job stress has been linked to medical and psychiatric conditions, including depression6,7 and cardiac disease.8,9 In health care workers, job stress has been linked to reduced quality of patient care.10

Studies have demonstrated that physical therapists may experience high levels of job stress,11–15 but the scope of the problem is difficult to determine. Research to date has consisted mostly of interview and focus group studies.11,12,15

Different dimensions of work stress have been studied in physical therapists, but common themes have emerged. Common sources of work stress have included excessive workloads (both clinical and administrative) and a lack of resources (equipment, staffing, and time).11–15 The professional culture in physical therapy may complicate the work environment. Physical therapists hold themselves to high professional standards and may experience a conflict between clinical realities and personal ideals.12,14 In the face of external pressures, including increasing workloads and job demands, job stress may be viewed as a personal failing.

Job stress is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon with a variety of contributing factors.16 The psychosocial work environment is a major (but not the only) contributor. It is defined by workers’ perceptions of social, environmental, and organizational factors in their jobs.16 Studies to date on physical therapists provide evidence of potential issues in the psychosocial work environment that may cause job stress. These issues include perceptions of excessive work demands, a loss of control, a lack of support, frustration with clients, and difficulty with professional relationships.11–15,17 The findings from these studies, however, may not apply to typical physical therapists working in a variety of settings. Little research has explored the psychosocial work environment for physical therapists nationally; therefore, this is an area that is not well understood. No studies have compared the psychosocial work environment for physical therapists with the psychosocial environments in other occupations. New studies of the physical therapy work environment with larger samples are needed.

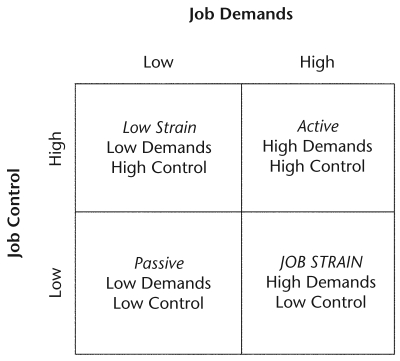

Two aspects of the psychosocial work environment that are frequently studied in occupational health psychology are job demands and job control. The demand and control model of Karasek and colleagues18 proposes that job strain, a combination of high demands and low control, increases the risk for poor outcomes.19 The following is an analysis of job demands, job control, and job strain in physical therapists. It was based on a prospective cohort study of WMSDs in physical therapists.20

Increased demands, reduced control, and job strain have been associated with a wide variety of outcomes, including turnover3 and WMSDs.21 Both are important outcomes to consider in physical therapy. Some physical therapy settings have turnover rates that are substantially higher than national averages,22,23 and turnover can result in substantial costs in health care settings.24 Work-related musculoskeletal disorders also are an important outcome to consider in physical therapy. Some authors have reported high rates of work-related pain in physical therapists,20,25 and WMSDs have consistently been associated with job strain in other populations.21,26

The purposes of this study were: (1) to determine the levels of job demands and control in physical therapists, (2) to compare levels of demands and control in physical therapists with levels of demands and control in other occupations, and (3) to explore whether increased demands, reduced control, or a combination of both (job strain) leads to an increased incidence of job turnover and increased incidence of WMSDs.

Method

Study Design

This was a prospective cohort study with 1-year follow-up. Data were collected via 2 validated postal questionnaires mailed 1 year apart. Exposure (ie, job strain) and demographic data were gathered at baseline. Outcomes (ie, musculoskeletal complaints and job turnover) were assessed at follow-up.

Participants

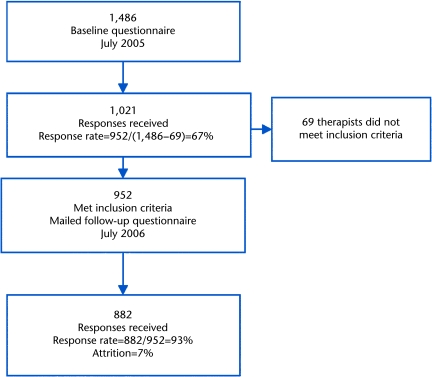

The sample consisted of randomly selected members of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). The APTA selected 1,500 members via random Microsoft Access* query. The number of therapists initially selected was limited by the project resources. Of the 1,500 members selected by APTA, 1,486 were determined to be eligible (some did not reside in the United States or were students). The initial questionnaire was mailed to 1,486 potential participants. One year later, a follow-up questionnaire was mailed to every individual who met the inclusion criteria and who responded to the baseline questionnaire.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the study, a participant had to be working as a physical therapist with at least 1 hour per week of patient care. He or she had to be an APTA member and return the baseline questionnaire. There were no exclusion criteria.

Exposure Assessment

Job demands, job control, and job strain were evaluated using scales from the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ), a commonly used occupational psychosocial assessment tool.18 The JCQ has been used to study a wide variety of outcomes in a broad range of occupations. The JCQ has yielded reliable and valid data across countries and occupational groups.18

The core of the job strain model focuses on the interaction between job demands and job control (Fig. 1).18 In this model, excessive work demands can be problematic but only when accompanied by a person's lack of control over his or her work situation. High demands coupled with high control (active jobs) and low demands coupled with low control (passive jobs) are thought to be less problematic.

Figure 1.

Demand and control model.

Job demands were assessed with 5 questions that were combined to form one scale (psychological demands). Job control was assessed with 9 questions comprising 2 scales. These 2 scales were decision authority (a measure of the ability to make decisions) and skill discretion (how varied and skilled the position is). A combination of high demands and low control was classified as job strain. Scores on the job demands scale range from 12 to 48, with higher scores representing higher demands. Scores on the job control scale range from 24 to 96, with higher scores representing higher control.27

Demands and control were dichotomized based on the median scores for each scale. Therapists with job demands above (but not including) the median score were classified as having high demands. Therapists with job control scores below (but not including) the median score were classified as having low control. Therapists with both high demands and low control were classified as having job strain. Medians are a common choice for classification thresholds,28,29 and sample medians have been used for dichotomization of demands and control in several recent prospective cohort studies with large samples.9,29,30

Outcome Assessment

The follow-up questionnaire included items on job turnover, stopping work, and job rotation. Turnover was defined as a situation where a therapist left one job and started work for another employer. Situations where therapists rotated within their facility or stopped working were not considered to be turnover. Therapists who rotated were retained for the turnover analysis. Therapists who retired or stopped working and did not return to work by the time the follow-up questionnaire was completed were not included in the turnover models.

Questions on WMSDs were included in both the baseline and follow-up questionnaires. An incident WMSD was defined as one that was experienced during the follow-up year and was not present at any time during the year prior to the baseline survey. In a prior study of WMSDs from this cohort,20 the researchers found that many of the therapists with incident WMSDs had complaints of work-related pain in the year prior to the baseline survey that progressed in terms of severity, duration, or frequency. They also found that many therapists had moderate work-related pain that was not severe enough to reach a stringent case definition. The case definition for this analysis was modified so that it captured all new cases of work-related pain. This modified case definition avoided missing therapists with moderate pain that did not reach the previous case threshold. It also avoided capturing therapists who had pain that did not reach the previous case threshold during the baseline year but progressed enough to qualify as cases during the follow-up year.

Data Entry

Data were entered twice into separate files using SPSS Data Entry Builder version 4.† Discrepancies were checked against the questionnaires and changed in the master data entry file if they were coding errors. Random samples of 20 questionnaires (at baseline and follow-up) then were selected and checked against the master data file.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 16† and Stata IC version 10.‡ The data were screened for missing or implausible values. Descriptive and frequency statistics were generated for all background, exposure, and outcome data. Demographic characteristics were compared with the APTA membership profile.31

The 3 scales (psychological demands, decision authority, and skill discretion) were totaled according to specific formulas.27 Decision authority and skill discretion were added together to form decision latitude (job control). Scale totals were compared with national averages from 2 studies with large samples: the Quality of Employment Surveys (QES) and another, more-recent national health survey, the New England Medical Center (NEMC) Study.18

Associations among job strain, turnover, and work-related musculoskeletal symptoms were evaluated using unconditional, multivariate logistic regression. Potential confounding factors, including sex, age, experience, hours worked per week at primary job, total hours worked per week, and holding a second job, were evaluated for association with job strain and with outcomes.32 When a confounder was at least moderately associated (P<.25) with both exposure and outcome, or if there was a theoretical justification for inclusion, it was retained for the multivariate model and retained throughout the modeling process.

Job strain and confounding factors were entered simultaneously into a multivariate model. Plausible interactions among job strain and main effects predictors were generated and backward eliminated. Plausible interactions included age versus job strain and sex versus job strain. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Goodness of fit was evaluated with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.33

This process was repeated for the dichotomized job demands and job control scales (included in the same model), and separate models were developed for turnover and for work-related musculoskeletal symptoms. Ratio-level confounding factors retained for the models were dichotomized based on the median values.

Pilot Testing

The questionnaire was pilot tested with repeat mailings 1 month apart. Eighteen therapists responded to both questionnaires. Test-retest stability (intraclass correlation coefficient, 2-way mixed model for absolute agreement)34 of the JCQ scales was good for decision authority (.71) and psychological demands (.69) but poor for skill discretion (.35).35

Role of the Funding Source

This project was supported by 2 National Institutes of Health Extramural Research Development Awards (grant HD 035965), a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Education and Research Center Pilot Project Award (T42 OH008422), and a Smart Family Foundation Grant. The grants were used to cover direct and indirect expenses related to the pilot studies and the full project. Dr. Koenig's work was supported, in part, by a Center grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES00260). None of the funding sources were involved with the design and methods of the project or had any influence on the way the study was conducted.

Results

Response

Figure 2 details the number and percentage of therapists who responded at each step of the study.

Figure 2.

Response rates and sample size.

Missing Values

None of the questions had more than 5% missing values, with most questions having 5 or fewer total missing values. Thirteen therapists did not answer one of the questions related to demands. Missing values for these questions were not replaced. Seven therapists did not answer the question related to turnover. Most of those therapists, however, reported one of the other job outcomes (stopping work or rotating positions). Those therapists were assumed not to have changed jobs. One therapist did not specify his or her sex.

Twenty-five therapists did not answer the question related to age, and 5 therapists did not answer the question related to work hours. Those values were replaced by the sample medians prior to logistic regression because they were considered to be confounding factors and not primary risk factors. One therapist did not answer the question about second jobs. That therapist was assumed not to have a second job.

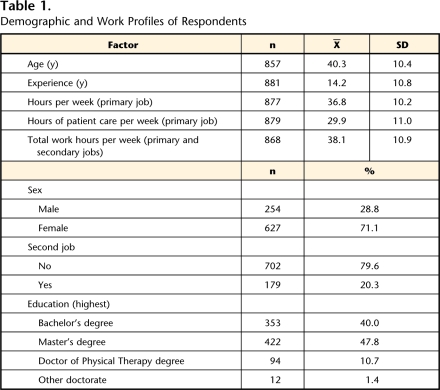

Demographics

The demographic profile of respondents is shown in Table 1. The profile was generally similar to that of the APTA membership,31 although the therapists in our sample were younger (1.3 years) and less experienced (2 years) on average. Practice settings generally were similar.

Table 1.

Demographic and Work Profiles of Respondents

Job Demands and Job Control in Physical Therapists

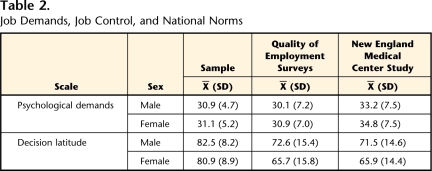

Scale means and standard deviations were compared with data from the QES and the NEMC Study (Tab. 2). Respondents reported a moderate level of demands and substantially higher levels of control than workers from the QES and NEMC Study surveys.18

Table 2.

Job Demands, Job Control, and National Norms

According to norms from the QES, the therapists in our sample were in the “active” job category—a combination of high demands and high control. The mean of job demands, however, was only marginally higher than the national average from the QES for both men and women, and both male and female therapists reported slightly lower levels of demands than the NEMC Study averages.

Turnover

One hundred thirty-seven therapists (16%) changed jobs during the year prior to the follow-up survey. In addition, 21 therapists (2%) left their jobs and were not working or were retired at follow-up. Sixty-one therapists (7%) rotated positions within their facility during the year prior to follow-up.

Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders

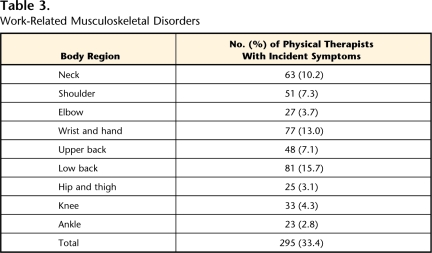

Fifty-eight percent of the therapists experienced a work-related ache or pain during the year prior to the follow-up survey. The most common region was the low back, followed by the wrist and hand. Two hundred ninety-five therapists (33.4%) experienced incident symptoms (ie, symptoms during the follow-up year that were not preceded by symptoms in the same body region in the year prior to the baseline survey) (Tab. 3).

Table 3.

Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders

Potential Confounders

Age and sex were included in all of the multivariate models. Older therapists were less likely than younger therapists to report changing jobs (OR=0.50, P<.01). Older therapists also were less likely to report job strain (OR=0.59, P<.01) and low job control (OR=0.66, P<.01). Female therapists were more likely than male therapists to report changing jobs (OR=1.51, P=.06). Female therapists also were more likely to report low job control (OR=1.38, P=.03).

Work hour measures and holding a second job were not associated with either outcome and were excluded. Experience was highly correlated with age (r=.89) and also was excluded.

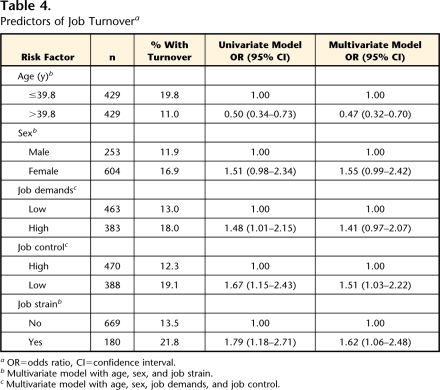

Job Strain and Job Turnover

Associations between psychosocial factors and turnover are summarized in Table 4. High job demands increased the likelihood of turnover (OR=1.41, 95% CI=0.97–2.07). Low job control also increased the likelihood of turnover (OR=1.51, 95% C=1.03–2.22). Job strain, which combines these 2 variables, was more strongly associated with the risk of turnover (OR=1.62, 95% CI=1.06–2.48) than either job demands or job control alone. No significant interactions were noted between age or sex and job strain, job demands, and job control.

Table 4.

Predictors of Job Turnovera

OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval.

bMultivariate model with age, sex, and job strain.

cMultivariate model with age, sex, job demands, and job control.

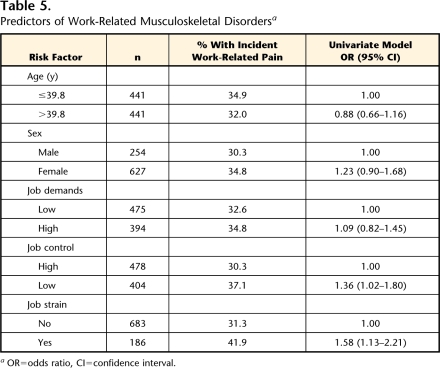

Job Strain and Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders

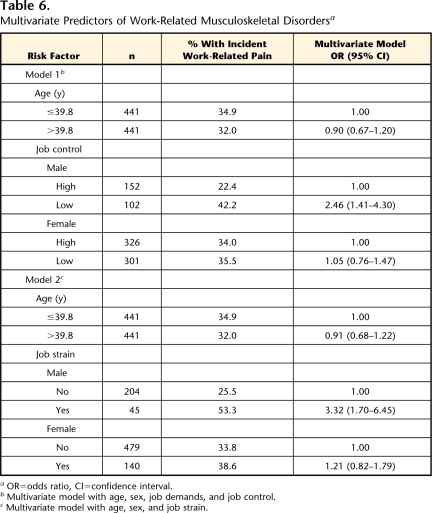

Associations between psychosocial factors and WMSDs are listed in Tables 5 and 6. Both job strain and job control were associated with work-related pain. Interactions between sex and job control (P=.01) and sex and job strain (P=.01) were noted. As shown in Table 6, low job control increased the likelihood of work-related musculoskeletal symptoms in men (OR=2.46, 95% CI=1.41–4.30) but not in women (OR=1.05, 95% CI=0.76–1.47). Job strain also increased the likelihood of work-related musculoskeletal symptoms in men (OR=3.32, 95% CI=1.70–6.45) but had little effect in women (OR=1.21, 95% CI=0.82–1.79). High job demands did not affect the likelihood of work-related musculoskeletal symptoms in men or women.

Table 5.

Predictors of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disordersa

OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval.

Table 6.

Multivariate Predictors of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disordersa

OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval.

bMultivariate model with age, sex, job demands, and job control.

cMultivariate model with age, sex, and job strain.

Discussion

Job Demands and Job Control

Physical therapists’ perceptions of their work environments generally were very positive. In comparison with other professions, physical therapy was seen as profession with moderate demands and high levels of control. In the demand/control model, physical therapy could have been considered an “active” job or a “low-strain” job, depending on the study used to establish a reference for job demands. In either formulation, the therapists in our sample, on average, felt that they had substantially higher levels of control over their work situations than the typical workers from prior studies.18 It should be noted that the decision authority and skill discretion subscales (added to form job control) had substantially higher levels of control than national averages, in both sexes.18 Thus, job control in this sample resulted from perceptions of control over workplace decisions (decision authority) as well as from feelings that therapy jobs were interesting, varied, and required high levels of skill (skill discretion).

Prior studies of job stress in physical therapists highlighted issues associated with the work environment, including lack of resources and excessive workloads.11–14 Work environments were viewed more positively in our sample. Prior studies consisted of small-sample surveys or focus group studies and may have differed in terms of population characteristics or representativeness. It also is possible that different aspects of the psychosocial work environment were considered.

The JCQ has demonstrated consistent differences in scale averages by sex. Karasek et al18 have pointed to systematic sex differences in work authority and opportunities to use and develop skills. Unlike the QES and the NEMC surveys, where women have reported higher demands and lower control, the differences between men and women were negligible in this sample.18 Women reported slightly higher demands and slightly lower control.

Job Strain and Job Turnover

About 16% of the therapists in this sample changed jobs during the year prior to the follow-up survey. This rate was identical to the rate in acute care hospitals according to surveys by APTA.23 Other settings in physical therapy, such as nursing homes, have reported even higher rates (85%).22 These rates substantially exceeded monthly national averages for US workers in the same year (3.0%–4.5%).36

The costs of turnover in this population could be substantial, but they are difficult to quantify. The costs can involve reduced productivity, overtime for current staff, training for new staff, and vacant periods between departures and hires. Jones37 calculated that turnover in nursing could result in costs that ranged from $62,100 to $67,100 per registered nurse. Waldman et al24 estimated that turnover costs at a major medical center exceeded 5% of the total annual operating budget.

Job strain increased the risk of turnover substantially. This association was consistent with prior studies.3,38 Turnover may have resulted from a variety of unexamined factors, including a relatively open job market,39 but psychosocial work conditions, including job strain, may have played an important role. Increased demands and reduced control, individually, also were associated with an increased likelihood of turnover. Mitigation of demands, increasing control, or both may reduce turnover among physical therapists.

Job Strain and Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders

About one third of the therapists in this sample reported an incident WMSD (incidence=33%). This incidence was higher than in a prior analysis of this sample in which a more-stringent case definition was used (incidence=20.7%).20 In the prior analysis, the researchers found that many of the therapists with incident WMSDs had complaints of work-related pain in the year prior to the first survey that progressed in terms of severity, duration, or frequency and then qualified as incident cases. The rate was higher in this analysis because a less-restrictive definition was used. Using the current definition, minor cases were more likely to be included, but all new cases were captured. The issue of musculoskeletal disorders in physical therapists is discussed more fully elsewhere.20,25

Job strain has been associated with work-related musculoskeletal symptoms in a variety of populations,5,40 including nurses21,26 and physical therapists.20 In this sample, job strain led to work-related pain in men only. This finding stands in contrast to the study by Karlqvist et al,41 who found an association between job strain and musculoskeletal symptoms in women but not men. Vermeulen and Mustard42 found higher levels of distress related to job strain in men than in women. Blackmore et al6 found that job strain led to depression in men but not in women. Explanations offered by the authors included different distributions of men and women in particular jobs and shorter work hours by women on average. In this sample, men and women tended to work in different settings, but there was no evidence that this factor was responsible for the sex differences in the effects of job strain.

A greater percentage of men than women worked in private practice settings. A greater percentage of women than men worked in skilled nursing facilities, home care, hospitals, and school systems. Men and women in private practice who reported job strain developed work-related pain in substantially higher percentages (men=54%, women=51%) than in other settings. Adding setting (private practice versus non–private practice), however, had negligible effects on the multivariate model for work-related pain. Future studies with a focus on specific settings are needed.

Implications

Levels of psychological demands in physical therapy generally are similar to the levels of demands in other professions. Levels of self-reported job control appear to be higher in physical therapy than in other professions. Therapists with perceptions of job control that are lower than typical for physical therapists, however, are at risk for both turnover and WMSDs. High levels of decision latitude, therefore, may be needed to perform the job adequately. Additional research is needed to determine the specific aspects of physical therapy work that are associated with perceptions of control.

Insights into specific factors that lead to perceptions of reduced control can be found in prior research. In a qualitative study, Blau et al15 examined the effects of hospital restructuring on physical therapy staff members at a large academic medical center. The therapists felt they had lost control over their work environment in the face of increasing work demands and constantly shifting policies. As a result, the therapists felt that they could not provide the best quality of care for their patients. They referred to stress, burnout, and frustration. Some of them actively considered quitting. In hospitals, perceptions of control, therefore, may be related to administrative policies and requirements, as well as the ability to care for patients adequately.

One of the tenets of the demand control model is that a combination of high demands and low control (job strain) results in greater risks than high demands or low control alone. This was true in this sample. The combination of both high demands and low control resulted in higher rates of both outcomes than either alone. It should be noted that the definition and coding of job strain in this analysis was relatively conservative (job strain/no job strain). A variety of job strain formulations, including a quadrant model using all 4 job classifications (high strain, low strain, active, and passive), have been proposed.28 In a quadrant model, low-strain situations are compared with high-strain situations. In this model, job strain was compared with all job situations without job strain. This was a more-conservative contrast.

Recommendations

The findings from this analysis highlight important considerations for therapists, both as they choose jobs for the first time and as they look for new positions after some degree of experience. Typical issues for consideration include salary and benefits, setting, educational and advancement opportunities, and workload. Other aspects of the work environment—the amount of control the therapist perceives, in particular—may be important factors in determining whether a physical therapist has a successful and rewarding tenure at a particular facility. A job with a positive psychosocial work environment may reduce the risk of injury and work-related pain, result in a better quality of patient care, and help to prevent turnover.

Employers may be reluctant to take measures to improve the psychosocial work environment, particularly any measure that results in reduced patient loads. Such measures, however, may pay for themselves if turnover or injuries can be avoided. Some of the ways in which employers may improve the psychosocial work environment include careful consideration of issues such as workload and administrative policies. Specifically, they should consider the number of patients seen each day, quality of patient care, professional development, time allotted for paperwork, consistency of organizational policies, and therapist input into organizational decisions.

Limitations

Only limited dimensions of the work environment were included in this study. One of the most commonly cited limitations of the JCQ is the multidimensional nature of work stress. The JCQ itself has several additional scales that are routinely used and recommended. These scales include coworker support, supervisor support, and job satisfaction.27 Additional studies with varied instruments are needed to explore other aspects of the psychosocial work environment of physical therapists.

Another common criticism of the JCQ relates to the value of self-reports and associated potential recall bias. Prospective designs, however, help to mitigate recall bias, and the JCQ has proven to have validity across occupations and cultures.18

Demand and control survey averages from the QES represent data that were collected a relatively long time ago (throughout the 60s and 70s). Although the questions from the JCQ are valid for use in today's workforce, caution should be exercised when comparing scale averages with a modern sample. In general, the JCQ has remained a practical and suitable tool for occupational health studies, and several recent studies have successfully used the JCQ with regard to a variety of outcomes.43–47

Therapists with low control in this sample had low control compared with other therapists in the sample—not national norms. The effects of low job control can only be interpreted in relation to the levels of control typical for physical therapy.

The low reliability of the skill discretion scale in this sample was another limitation. It is possible that ratings of skill discretion were either inaccurate or unstable over relatively short time periods. In that case, the null hypothesis of no effect due to job control would have been more likely than was demonstrated. It should be noted, however, that the sample size of the test-retest stability study was very low (n=18) and highly influenced by 2 cases. In other samples and over time, the JCQ has proven to be reliable and stable.18

Conclusions

Physical therapists view their work situations very positively. Physical therapists have a moderately demanding work environment and very high levels of control compared with other professions, and they may require these high levels of control to perform their jobs adequately.

Job strain, within this sample, was associated with turnover and work-related musculoskeletal symptoms. The psychosocial work environment is an important consideration for both therapists and employers. Physical therapists should consider the psychosocial work environment before choosing a first position or a new position.

More studies are needed to describe the characteristics of positive work environments in this population. Initiatives in specific facilities that improve the psychosocial work environment for physical therapists also should be developed and studied.

All authors provided concept/idea/research design and writing. Dr Campo provided data collection, project management, fund procurement, participants, and facilities/equipment. Dr Campo and Dr Koenig provided data analysis.

This work was conducted as part of Dr Campo's doctoral dissertation in the Program in Ergonomics and Biomechanics at New York University.

The materials and methods of this project were reviewed and approved by the University Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects (UCAIS) at New York University.

This research, in part, was presented at the Combined Section Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association; February 9–12, 2009; Las Vegas, Nevada, and at the Safe Patient Handling and Movement Conference; March 29-April 3, 2009; Lake Buena Vista, Florida.

This project was supported by 2 National Institutes of Health Extramural Research Development Awards (grant HD 035965), a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Education and Research Center Pilot Project Award (T42 OH008422), and a Smart Family Foundation Grant. The grants were used to cover direct and indirect expenses related to the pilot studies and the full project. Dr. Koenig's work was supported, in part, by a Center grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES00260). None of the funding sources were involved with the design and methods of the project or had any influence on the way the study was conducted.

Microsoft Corp, One Microsoft Way, Redmond, WA 98052-6399.

SPSS Inc, 233 S Wacker Dr, Chicago, IL 60606.

StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Dr, College Station, TX 77845.

References

- 1.Escriba-Aguir V, Martin-Baena D, Perez-Hoyos S. Psychosocial work environment and burnout among emergency medical and nursing staff. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2006;80:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahola K, Hakanen J. Job strain, burnout, and depressive symptoms: a prospective study among dentists. J Affect Disord. 2007;104:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Croon EM, Sluiter JK, Blonk RW, et al. Stressful work, psychological job strain, and turnover: a 2-year prospective cohort study of truck drivers. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89:442–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Head J, Kivimaki M, Martikainen P, et al. Influence of change in psychosocial work characteristics on sickness absence: the Whitehall II Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause N, Ragland DR, Fisher JM, Syme SL. Psychosocial job factors, physical workload, and incidence of work-related spinal injury: a 5-year prospective study of urban transit operators. Spine. 1998;23:2507–2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackmore ER, Stansfeld SA, Weller I, et al. Major depressive episodes and work stress: results from a national population survey. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2088–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clays E, De Bacquer D, Leynen F, et al. Job stress and depression symptoms in middle-aged workers: prospective results from the Belstress study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2007;33:252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aboa-Eboule C, Brisson C, Maunsell E, et al. Job strain and risk of acute recurrent coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2007;298:1652–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornitzer M, deSmet P, Sans S, et al. Job stress and major coronary events: results from the Job Stress, Absenteeism and Coronary Heart Disease in Europe Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M. The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care: results from the MEMO study. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32:203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JR, Coombs CR, Wilkinson AJ, et al. Attractiveness of physiotherapy in the National Health Service as a career choice: qualitative study. Physiotherapy. 2003;89:575–583. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broom JP, Williams J. Occupational stress and neurological rehabilitation physiotherapists. Physiotherapy. 1996;82:606–614. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuster ND, Nelson DL, Quisling C. Burnout among physical therapists. Phys Ther. 1984;64:299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deckard GJ, Present RM. Impact of role stress on physical therapists’ emotional and physical well-being. Phys Ther. 1989;69:713–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blau R, Bolus S, Carolan T, et al. The experience of providing physical therapy in a changing health care environment. Phys Ther. 2002;82:648–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiser S. Psychosocial aspects of occupational musculoskeletal disorders. In: Hurley R, ed. Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Workplace: Principles and Practice. New York, NY: CV Mosby Co; 1997:51–61.

- 17.Mottram E, Flin RH. Stress in newly qualified physiotherapists. Physiotherapy. 1988;74:607–612. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, et al. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3:322–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity and the Reconstruction of the Working Life. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1990.

- 20.Campo MA, Weiser S, Koenig KL, Nordin M. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in physical therapists: a prospective cohort study with 1-year follow-up. Phys Ther. 2008;88:608–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahlberg-Hulten GK, Theorell T, Sigala F. Social support, job strain and musculoskeletal pain among female health care personnel. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1995;21:435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Physical Therapy Workforce Project: Physical Therapy Vacancy and Turnover Rates in Skilled Nursing Facilities. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association; 2008.

- 23.Physical Therapy Workforce Project: Physical Therapy Vacancy and Turnover Rates in Acute Care Hospitals. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association; 2008.

- 24.Waldman JD, Kelly F, Arora S, Smith HL. The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2004;29:2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cromie JE, Robertson VJ, Best MO. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in physical therapists: prevalence, severity, risks, and responses. Phys Ther. 2000;80:336–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Josephson M, Lagerstrom M, Hagberg M, Wigaeus Hjelm E. Musculoskeletal symptoms and job strain among nursing personnel: a study over a three year period. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:681–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karasek R. Job Content Questionnaire and User's Guide. Lowell, MA: University of Massachusetts; March 1985.

- 28.Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Warren K, et al. Association between ambulatory blood pressure and alternative formulations of job strain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1994;20:349–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clumeck N, Kempenaers C, Godin I, et al. Working conditions predict incidence of long-term spells of sick leave due to depression: results from the Belstress I prospective study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Achat H, Kawachi I, Byrne C, et al. A prospective study of job strain and risk of breast cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:622–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.APTA Membership and Demographic Profile. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association; 2005.

- 32.Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th ed. New York, NY: Pearson; 2007.

- 33.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2000.

- 34.McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Meth. 1996;1:30–46. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 5th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury; 2000.

- 36.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey. 2008. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/jlt/. Accessed May 6, 2008.

- 37.Jones CB. The costs of nurse turnover, part 2: application of the Nursing Turnover Cost Calculation Methodology. J Nurs Adm. 2005;35:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatton C, Emerson E, Rivers M, et al. Factors associated with intended staff turnover and job search behaviour in services for people with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2001;45(pt 3):258–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The APTA Employment Survey. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association; 2005.

- 40.Hoogendoorn WE, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, et al. High physical work load and low job satisfaction increase the risk of sickness absence due to low back pain: results of a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:323–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karlqvist L, Tornqvist EW, Hagberg M, et al. Self-reported working conditions of VDU operators and associations with musculoskeletal symptoms: a cross-sectional study focussing on gender differences. Int J Indus Erg. 2002;30:277–294. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vermeulen M, Mustard C. Gender differences in job strain, social support at work, and psychological distress. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5:428–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuboi H, Takeuchi K, Watanabe M, et al. Psychosocial factors related to low back pain among school personnel in Nagoya, Japan. Indus Health. 2002;40:266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ariens GA, Bongers PM, Hoogendoorn WE, et al. High physical and psychosocial load at work and sickness absence due to neck pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002;28:222–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersen JH, Kaergaard A, Frost P, et al. Physical, psychosocial, and individual risk factors for neck/shoulder pain with pressure tenderness in the muscles among workers performing monotonous, repetitive work. Spine. 2002;27:660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salminen S, Kivimaki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J. Stress factors predicting injuries of hospital personnel. Am J Indus Med. 2003;44:32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonde JP, Mikkelsen S, Andersen JH, et al. Prognosis of shoulder tendonitis in repetitive work: a follow-up study in a cohort of Danish industrial and service workers. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:E8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]