SUMMARY

Elevated plasma homocysteine (HCy), which results from folate (folic acid, FA) deficiency, and the mood-stabilizing drug lithium (Li) are both linked to the induction of human congenital heart and neural tube defects. We demonstrated previously that acute administration of Li to pregnant mice on embryonic day (E)6.75 induced cardiac valve defects by potentiating Wnt–β-catenin signaling. We hypothesized that HCy may similarly induce cardiac defects during gastrulation by targeting the Wnt–β-catenin pathway. Because dietary FA supplementation protects from neural tube defects, we sought to determine whether FA also protects the embryonic heart from Li- or HCy-induced birth defects and whether the protection occurs by impacting Wnt signaling. Maternal elevation of HCy or Li on E6.75 induced defective heart and placental function on E15.5, as identified non-invasively using echocardiography. This functional analysis of HCy-exposed mouse hearts revealed defects in tricuspid and semilunar valves, together with altered myocardial thickness. A smaller embryo and placental size was observed in the treated groups. FA supplementation ameliorates the observed developmental errors in the Li- or HCy-exposed mouse embryos and normalized heart function. Molecular analysis of gene expression within the avian cardiogenic crescent determined that Li, HCy or Wnt3A suppress Wnt-modulated Hex (also known as Hhex) and Islet-1 (also known as Isl1) expression, and that FA protects from the gene misexpression that is induced by all three factors. Furthermore, myoinositol with FA synergistically enhances the protective effect. Although the specific molecular epigenetic control mechanisms remain to be defined, it appears that Li or HCy induction and FA protection of cardiac defects involve intimate control of the canonical Wnt pathway at a crucial time preceding, and during, early heart organogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

The heart is the first organ to develop in the embryo and different regions of the heart, including the right and left ventricles and the outflow tract, are already specified at the gastrulation stages. The development is complex, involving two heart fields and the sequential activation of multiple signaling pathways together with regulation of genetic cascades in the cardiogenic crescent. Genetic and environmental effectors can severely impact these pathways and lead to abnormal development. Two factors, namely an elevated level of the metabolic intermediary homocysteine (HCy) and the therapeutic drug lithium (Li), have been a focus of birth defect research for over 30 years. Low dietary folate (folic acid, FA) and mutations in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) lead to elevated maternal plasma HCy levels. Elevated HCy increases the risk for neural tube, neural crest, craniofacial and congenital heart defects in the offspring (Boot et al., 2004; Huhta et al., 2006; Rosenquist et al., 1996; Tang et al., 2004). The association with elevated HCy is particularly strong for specific outflow tract defects, including pulmonary valve stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, and aortic valve stenosis (Huhta et al., 2006). Maternal Li therapy for bipolar disorder is similarly associated with neural, skeletal, craniofacial and cardiac valve defects, specifically of the tricuspid valve in association with Ebstein’s anomaly (Iqbal and Mahmud, 2001; Yonkers et al., 2004). Despite Li and HCy being linked with neural tube and heart defects, the etiology of the induced congenital defects associated with these chemicals has remained unknown.

With a long-term focus on defining heart developmental mechanisms and, specifically in relation to β-catenin, the important downstream intermediary of Wnt signaling (Linask, 1992; Linask et al., 1997), Li and HCy became specific targets of our studies to define the underlying mechanisms of certain cardiac birth defects and to understand the molecular origins. We observed that the phenotypic defects induced after a single exposure to Li during gastrulation (Chen et al., 2008) are similar to those reported by others for elevated HCy in a transgenic mouse model (Tang et al., 2004). Because of the similarities in the cardiac and neural anomalies induced by either HCy or Li exposure, and because Li is known to mimic Wnt–β-catenin signaling, we hypothesized that both HCy and Li may target canonical Wnt signaling during the same early developmental window, but that this modulation of the pathway occurs at different regulatory levels.

Clinically, Li continues to be considered as only a modest risk factor for the development of birth defects with first-trimester embryonic exposure (Cohen et al., 1994; Jacobson et al., 1992). Our experimental evidence, relating peak cardiac defects to an early timing of exposure during vertebrate gastrulation stages (Chen et al., 2008; Manisastry et al., 2006), means that the most susceptible exposure period for heart defects occurs before most women are aware they are pregnant. Moreover, evidence published since the mid-1990s suggests that the risk of birth defects arising from Li exposure during early pregnancy is high and can result in early embryonic lethality. This evidence includes: (1) Li mimics canonical Wnt signaling by inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) (Klein and Melton, 1996; Zhang et al., 2003); (2) canonical Wnt signaling regulates embryonic cell fate decisions, including those of precardiac cells (Ai et al., 2007); (3) Li and Wnt3A adversely impact cardiogenesis during gastrulation (Manisastry et al., 2006); (4) β-catenin functions in defining the cardiac compartment (Linask et al., 1997); (5) β-catenin promotes development of the right ventricle and outflow tract through Isl1 activation in the second heart field (SHF) (Lin et al., 2007); and (6) β-catenin regulates valvulogenesis (Chen et al., 2008; Hurlstone et al., 2003). Based on the aforementioned studies, and because Li mimics Wnt–β-catenin signaling, Li was hypothesized to pose a serious risk to the developing human embryo, specifically in relation to heart development. Because controversy has continued to exist regarding the effects of Li on cardiogenesis, we undertook a series of experiments to clarify its role in the induction of heart, specifically heart valve, defects and to compare it with the effects of elevated HCy, for which a similar experimental history and controversy have existed in relation to the heart.

The origins of the controversy derive from insufficient basic knowledge at the time of the previous investigations that identified the existence of two heart fields. The first heart field defines primarily the left ventricle and the second (anterior) heart field defines part of the right ventricle and outflow tract; the timing of the specification of the two heart fields coincides with gastrulation (de la Cruz et al., 1989; de la Cruz et al., 1991; Verzi et al., 2005). Using rodent or avian models, we targeted the embryo during the primitive-streak stage. Previous studies have exposed the embryo to Li or HCy, but only after a tubular cardiac structure was already present at E8.0, or later (Nelson et al., 1955; Rosenquist et al., 1996; Smithberg and Dixit, 1982). This communication compares our HCy exposure studies during gastrulation with the cardiac defects induced by Li and analyzes the common FA rescue of the defects.

In the avian model, all three of the molecules, that is, HCy, Li and Wnt3A, repress the Wnt–β-catenin-modulated genes Hex (also known as Hhex) and Isl1 in the cardiogenic regions. We subsequently sought to determine whether FA supplementation, which can substantially prevent HCy-related human neural tube defects (Huhta et al., 2006; Rosenquist and Finnell, 2001), would rescue the deleterious effects of Li, canonical Wnt3A or HCy on heart development in the experimental setting. We report that FA restores normal Hex and Isl1 gene expression and protects against the birth defects that are induced by the three factors. The addition of myoinositol synergizes with the FA protection following Li exposure. Our results, which are based on two different vertebrate models, demonstrate that the two dissimilar factors Li and HCy both potentiate the canonical Wnt pathway, which is a crucial pathway in early cardiogenesis and neurogenesis. This pulse of augmentation of Wnt signaling induces birth defects. The finding that FA can rescue direct canonical Wnt3A induction of embryonic defects indicates that FA metabolism intersects with canonical Wnt signaling to provide protection.

RESULTS

Avian model

HCy or Li exposure in avian embryos during Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stages 3+ to 5 induced similar heart defects

The peak time of sensitivity corresponded to HH stages 3+/4 to stage 5, in which 78% (n=128) and 68% (n=74) of embryos, respectively, that were exposed to elevated HCy (50 μM) displayed cardiac abnormalities, which were defined by immunolocalization of sarcomeric myosin heavy chain using MF20 antibody (Fig. 1). Exposure at HH stages 6 and 7 led to normal development. The main embryonic defects related to the timing of embryonic exposure; the regions that were primarily affected related to an anterior-to-posterior (AP) wave of development along this embryonic axis. The exposure effects ranged from early effects (e.g. no cardiac tissue, heart development occurring anterior to neural tissue, cardiabifida) to later effects, such as wide hearts and left looping (Table 1). The cardiac phenotypes observed with early HCy exposure were similar, although not identical, to those obtained from our studies of Li exposure on avian heart development (Manisastry et al., 2006).

Fig. 1.

Effects of exogenous HCy on early chick heart development after a 24-hour incubation. Immunolocalization of MF20 defines the presence of cardiac tissue (arrows). (A,B) Two extremes of cardiabifida: in A, two small cardiogenic regions are differentiating bilaterally; in B, the two heart fields have moved close to the midline, are almost touching, and are ready to fuse. (C) Light microscopic view of an embryo displaying a severely truncated neural tube with cardiac tissue differentiating cephalad to the neural area (D). (E) Bright-field ventral view of a normal, control, right-looping heart and (F) fluorescence view showing MF20 localization in the heart shown in E. In all panels, the embryonic anterior is at the top. Bars, 300 μm.

Table 1.

Early embryonic chick model: exposure to 50 μM HCy leads to cardiac defects

| Abnormality type | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Left looping* | 11 | 10.2 |

| Cardiabifida* | 11 | 10.2 |

| Wide heart* | 24 | 22.2 |

| Heart above head | 18 | 16.7 |

| Heart close to midline* | 15 | 13.9 |

| Tubular heart | 3 | 2.8 |

| Very abnormal (or no hearts) | 18 | 16.7 |

| Delayed development | 2 | 1.9 |

| Dead | 6 | 5.6 |

| Total | 108 | 100 |

Midline-related anomaly.

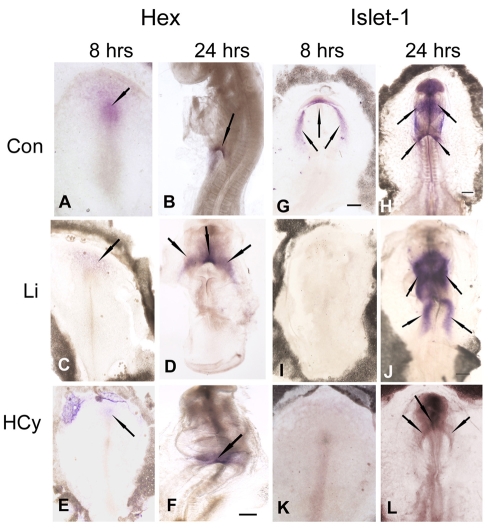

HCy and Li suppress Hex and Islet-1 (Isl1) gene expression in the avian heart fields

To extend our previous finding that Li suppresses Hex gene expression in the chick primary heart fields (Chen et al., 2008), we analyzed and compared the effects of HCy on the patterning of cardiac gene expression. The avian model allows for more precise targeting of exposure to specific early stages of development. Mouse embryos within a litter can vary widely in their developmental stages, leading to misinterpretation of results when, at the time of the acute exposure, the window of susceptibility for some embryos has already passed. In the Li study, we detected that the viable defects in the mouse embryo were related to derivatives of the SHF. Therefore, we also analyzed the effects of HCy and Li exposure on Isl1 expression, a SHF marker and one that is modulated by β-catenin in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway (Cai et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2007).

Chick embryos (HH stages 3+/4) were incubated on agarose-albumin supplemented with HCy (50 μM). Instead of giving a single injection in ovo, embryos were exposed to HCy for 8 hours in order to define the effect on early cardiac gene expression. Another group of embryos were exposed to HCy for 24 hours at which time the effects on gene expression were determined. To analyze the effects during the looping stages, incubation was stopped after between 22 and 24 hours. After the 8-hour incubation, Li and HCy suppressed Hex and Isl1 expression in the cardiogenic crescent (Fig. 2). In the untreated control embryo, Hex expression was apparent in the Hensen’s node region, anteriorly in the prechordal plate, and extending laterally (Fig. 2A). By 24 hours, Hex was still apparent in the anterior intestinal portal (AIP) endoderm in a looping HH stage 14 heart (Fig. 2B). Exposure to either Li (Fig. 2C) or HCy (Fig. 2E) for 8 hours decreased Hex expression in the prechordal plate. After exposure to Li for 24 hours, Hex was expressed in the AIP and cardiogenic regions of a developmentally delayed embryo (Fig. 2D). After exposure to HCy for 24 hours, the embryo had a looping heart with a truncated neural tube, and the AIP region displayed only diffuse Hex expression (Fig. 2F). By contrast, the control embryo had developed to a late-looping stage (Fig. 2B). If HCy or Li exposure occurred at HH stages 6 or 7, Isl1 expression was already activated and was similar to control embryos (not shown). In summary, 8 hours of Li or HCy exposure during the early stages of chick development repressed Hex and Is11 expression. By 24 hours, Isl1 gene expression had recovered but heart development and neural tube development were abnormal and remained delayed.

Fig. 2.

Hex and Islet-1 (Isl1) gene expression patterns after 8 and 24 hours in control embryos and in Li- or HCy-exposed embryos. (A,B,G,H) In control embryos (Con, top row), both Hex and Isl1 expression are seen at relatively high levels after an 8-hour (A,G) and 24-hour (B,H) incubation. The black arrows indicate in situ gene expression. Hex and Isl1 gene expression are suppressed in chick embryos following Li (C, second row) or HCy (E, bottom row) exposure at HH stages 3+/4–. A recovery in gene expression is noted by 24 hours (D,F), but embryos remain delayed in their development. Modulation of Isl1 is similar: little or no Isl1 gene expression is detectable following 8 hours of exposure to Li (I) or HCy (K). By 24 hours, heart development is delayed and cardiac anomalies arise (J,L). In all panels, the embryonic anterior is at the top. Bars, 300 μm.

FA protects against HCy- and Li-induced adverse effects in early chick cardiac development

Since FA can partially rescue HCy-induced neural- and neural crest-related defects in the mouse (Zhu et al., 2007), we determined whether cardiac defects could be rescued in the avian culture system. FA-supplemented medium rescued HCy- and Li-induced heart defects in embryos that were exposed between HH stages 3 and 5 (Table 2). At HH stages 3 and 4, FA supplementation at 10 μg/ml provided protection in embryos exposed to HCy (50 μM) or Li, with 54% and 48% of HCy- and Li-exposed embryos, respectively, displaying normal heart development. Without FA supplementation, only 22% and 28% of HCy- and Li-exposed embryos, respectively, had normal heart development. Of the HH stage 3/4 control embryos that had been treated with physiological saline, 48% showed normal development.

Table 2.

FA or inositol supplementation increases the percentage of normal heart development

| HH stage | Treatment* | Number of embryos | Abnormal embryos | Normal embryos | Normal hearts (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3+/4 | Control (NaCl) | 87 | 45 | 42 | 48% |

| 3+/4 | HCy | 128 | 100 | 28 | 22% |

| 3+/4 | HCy + FA | 57 | 26 | 31 | 54% |

| 5 | Control (NaCl) | 42 | 11 | 31 | 74% |

| 5 | HCy | 74 | 50 | 24 | 32% |

| 5 | HCy + FA | 22 | 6 | 16 | 73% |

| 3+/4 | FA only | 11 | 5 | 6 | 55% |

| 3+/4 | Inositol only | 5 | 2 | 3 | 60% |

| 3+/4 | Li only | 29 | 21 | 8 | 28% |

| 3+/4 | Li + FA | 40 | 21 | 19 | 48% |

| 3+/4 | Li + inositol | 30 | 18 | 12 | 40% |

| 3+/4 | Li + FA + inositol | 34 | 9 | 25 | 74% |

Concentrations used: HCy, 50 μM; Li, 50 μM; FA, 10 μM; inositol, 50 mM.

There was an association between the severity of defects and the developmental stage at exposure. HCy exposure (50 μM) beginning at HH stage 5 resulted in normal cardiac development in 32% of embryos. With FA supplementation, 73% of HH stage 5 embryos had normal cardiac development. In summary, FA rescued cardiac defects, but was less effective at the early stages of development when the HCy- or Li-induced defects would be embryonic lethal.

Inclusion of FA and inositol is additive, and increases the percentage of Li-exposed embryos that display normal development

In addition to mimicking canonical Wnt signaling, Li modulates phosphatidylinositol signaling (Belmaker et al., 1998). We thus analyzed whether the combination of inositol (50 mg/ml) and FA supplementation would result in a higher percentage of embryos with normal heart development within the more severely affected HH stage 3+/4 group (Table 2). FA supplementation or inositol alone produced similar percentages of normal heart development (55% and 60%, respectively) compared with the control group (48%). A combination of inositol and FA was additive and, in the presence of Li, increased normal development to 74% in in vitro culture conditions.

FA protects against Wnt3A-induced heart defects

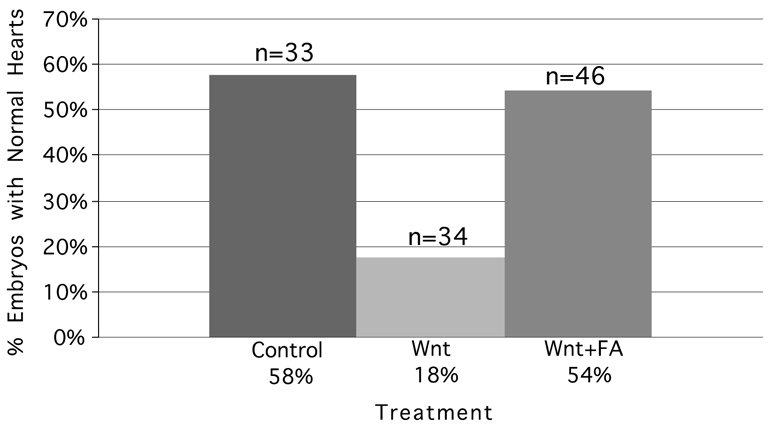

Since both HCy and Li seemed to modulate the canonical Wnt pathway during the cardiac specification stages, we speculated and confirmed that FA should rescue the deleterious effects of canonical Wnt3A (Manisastry et al., 2006) on heart development (Figs 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

FA supplementation with embryonic Wnt3A exposure at HH stages 3+/4 increases the percentage of normal heart development. Of the embryos in the control group, 58% displayed normal development in contrast to 18% of embryos in the Wnt3A-exposed group. FA supplementation increased the percentage of Wnt3A-exposed embryos with normal development to the level seen in the control group.

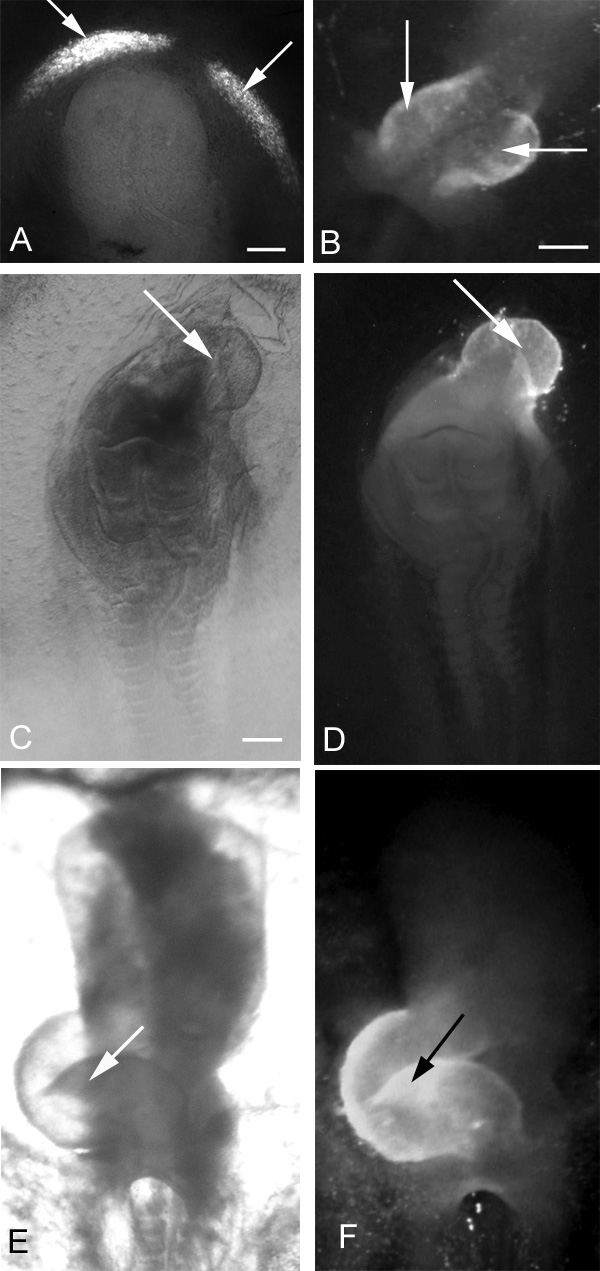

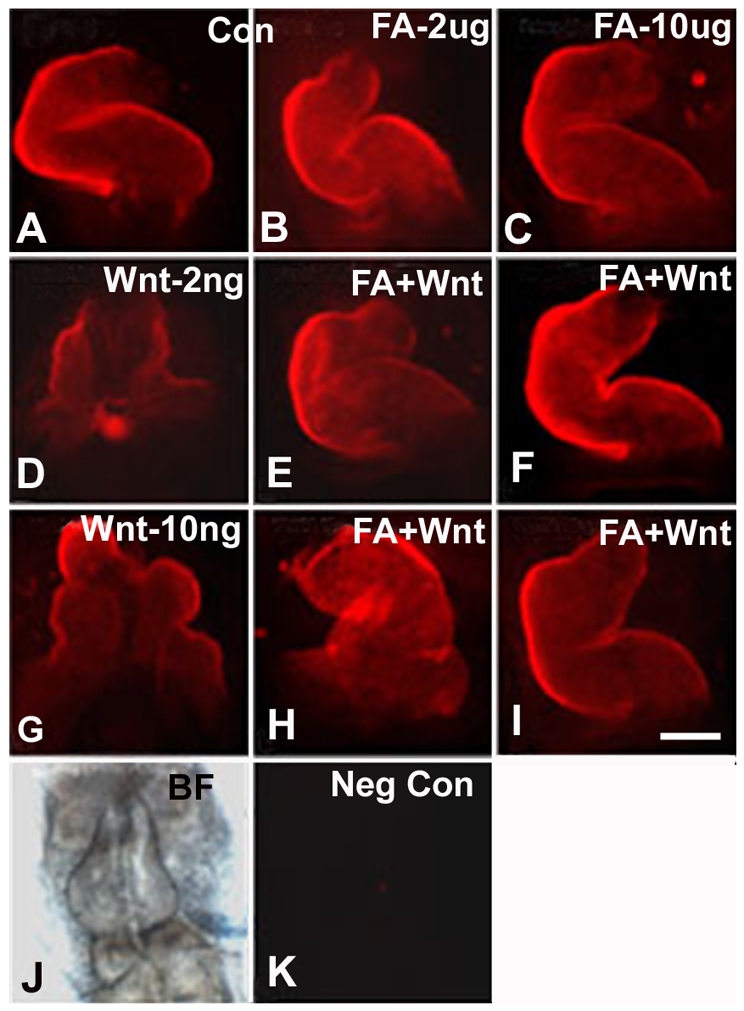

Fig. 4.

FA rescues heart development of Wnt3A-exposed embryos immunostained with MF20 antibody. (A–C) Control embryonic hearts in whole mounts: (A) untreated control (Con) embryo; (B) FA exposure only, 2 μg/ml; and (C) FA exposure only, 10 μg/ml. HH stages 3+/4 embryos exposed to 2 ng/ml (D) or 10 ng/ml (G) of Wnt3A display abnormal heart development. FA supplementation at a concentration of 2 μg/ml rescues embryonic heart development at the 2 ng/ml Wnt3A concentration (E), but only partially rescues heart development in embryos exposed to 10 ng/ml of Wnt3A (H, left-looping heart). FA supplementation at a concentration of 10 μg/ml completely normalized heart development with either a low or high level of Wnt 3A exposure (F,I). (J) Bright-field view of the embryo shown in K, a negative control without primary antibody treatment. In all panels, the embryonic anterior is at the top. Bar, 275 μm.

The minimal effective doses of Wnt3A that induced cardiac and neural anomalies were 2 ng/ml and 10 ng/ml, respectively. Using these concentrations, we then analyzed whether FA supplementation of media at 103-fold higher concentrations, that is 2 μg/ml or 10 μg/ml, would provide protection against the augmentation of canonical Wnt3A signaling. With only Wnt3A exposure at HH stages 3+/4, 18% of embryos had normal hearts; Wnt3A media supplemented with FA rescued normal heart development (54%) to near control levels (58%) (Figs 3 and 4). A normal looping control heart is shown with MF20 immunolocalization of sarcomeric myosin heavy chain (Fig. 4A). The addition of FA alone, at a concentration of 2 μg/ml or 10 μg/ml, resulted in normal heart development (Fig. 4B,C, respectively). Embryos exposed to 2 ng/ml of Wnt 3A (Fig. 4D) displayed incomplete cardiac tube formation, whereas those exposed to 10 ng/ml displayed cardiabifida (Fig. 4G). Wnt3A (2 ng/ml) in the presence of 2 μg/ml (Fig. 4E) or 10 μg/ml (Fig. 4F) of FA supplementation resulted in normal heart development. At the higher Wnt 3A concentration (10 ng/ml) (Fig. 4G–I), FA supplementation at the 2 μg/ml level provided only partial rescue of tube formation (Fig. 4H), and left-looping hearts were observed occasionally. The higher FA concentration (10 μg/ml) also rescued heart development in the high Wnt3A exposure group (Fig. 4I). To summarize, FA suppressed the effects of direct Wnt3A potentiation of canonical Wnt signaling and normalized development.

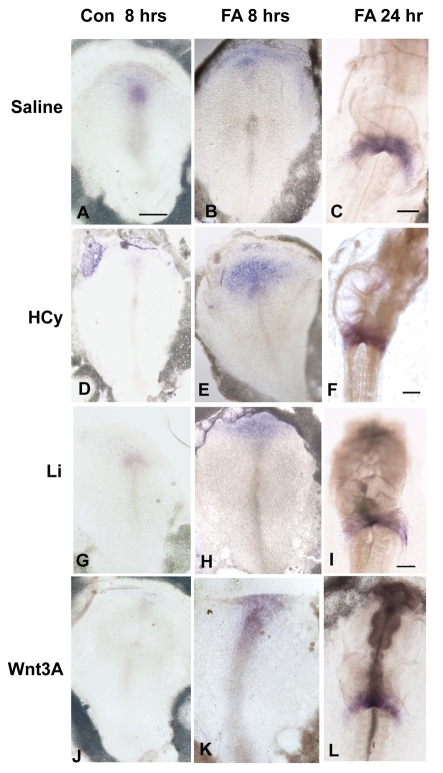

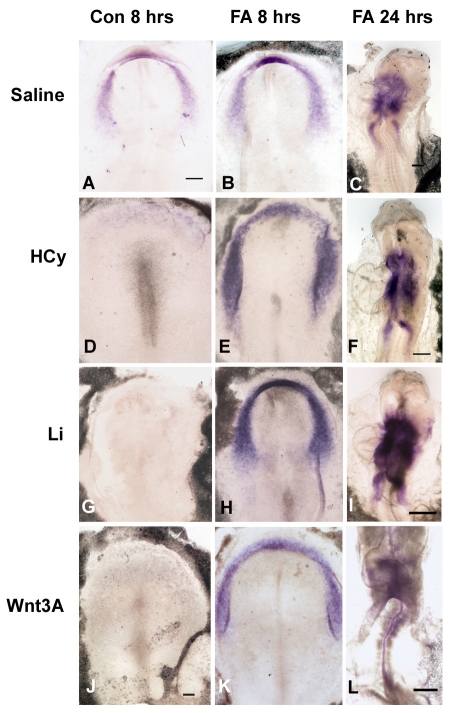

FA rescues Li-, HCy- and Wnt3A-induced misexpression of Hex and Isl1 at the gastrulation stages

We analyzed whether FA rescues the downregulation of Hex and Isl1. Chick embryos were exposed to Li, HCy or Wnt3A, as above, with and without 10 μg/ml of FA; the experiments were terminated after either an 8-hour or 24-hour exposure period, at which time in situ hybridizations for gene expression were performed. After 8 hours of exposure, Li, HCy and Wnt3A all suppressed Hex (Fig. 5D,G,J) and Isl1 (Fig. 6D,G,J) compared with the control embryonic expression patterns (Fig. 5A; Fig. 6A). FA supplementation for 8 hours resulted in normalized gene expression patterns and the expression was at higher levels than in control embryos [Fig. 5B,E,H,K (for Hex); Fig. 6B,E,H,K (for Isl1)]. By 24 hours, normal beating hearts had formed and normal Hex (Fig. 5C,F,I,L) and Isl1 (Fig. 6C,F,I,L) gene expression was apparent in the developing atrial region in the SHF. Thus, FA supplementation suppressed the potentiation of the inhibitory Wnt signaling, allowing for normal induction of Hex and Isl1 gene expression.

Fig. 5.

FA rescues Hex expression in Li-, HCy- and Wnt3A-exposed embryos. (A–C) Normal patterns of Hex expression in control embryos (saline added) after 8 hours (A), and after FA-only exposure at 8 hours (B) and at 24 hours (C). (D–F) Gene expression in embryos exposed to only HCy for 8 hours (D), and to HCy with FA supplementation for 8 hours (E) and 24 hours (F). (G–I) Gene expression in embryos exposed to only Li for 8 hours (G), and to Li with FA supplementation for 8 hours (H) and 24 hours (I). (J–L) Gene expression in embryos exposed to only Wnt3A for 8 hours (J), and to Wnt3A with FA supplementation for 8 hours (K) and 24 hours (L). In all panels, the embryonic anterior is at the top. Bars, 300 μm.

Fig. 6.

FA rescues Isl1 expression in Li-, HCy- and Wnt3A-exposed embryos. (A–C) Normal patterns of Isl1 expression in control embryos (saline added to medium) after 8 hrs (A), and after FA-only exposure at 8 hours (B) and at 24 hours (C). (D–F) Gene expression in embryos exposed to only HCy for 8 hours (D), and to HCy with FA supplementation for 8 hours (E) and 24 hours (F) (G–I) Gene expression in embryos exposed to only Li for 8 hours (G), and to Li with FA supplementation for 8 hours (H) and 24 hours (I). (J–L) Gene expression in embryos exposed to only Wnt3A for 8 hours (J), and to Wnt3A with FA supplementation for 8 hours (K) and 24 hours (L). In all panels, the embryonic anterior is at the top. Bars, 300 μm.

Mouse model

Doppler ultrasound assessment of Li and HCy exposure on embryonic mouse heart function

To determine whether our results in the avian system would extend to the mammalian system, we conducted studies in the mouse embryo. We studied the effects of increased maternal HCy serum levels by acute targeting of the same E6.75 developmental window that induced cardiac defects with Li exposure. Doppler ultrasound was used to monitor non-invasively the effects on heart and placental function.

The maternal and embryonic hemodynamic variables measured by Doppler ultrasonography on E15.5 embryos are shown in Fig. 7, and a comparison between the HCy and Li echo data is provided in Tables 3 and 4. The significant differences are highlighted below.

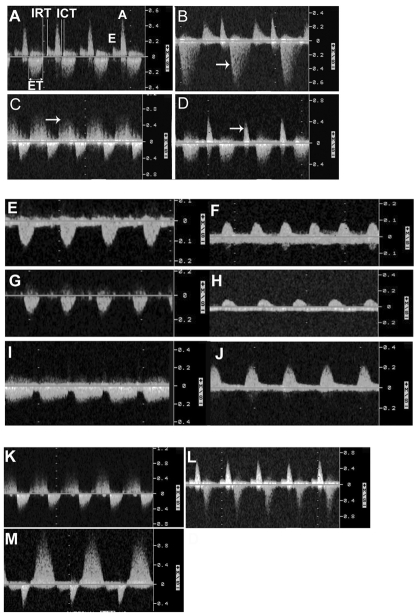

Fig. 7.

Doppler velocity waveforms of blood flow on E15.5. Inflow is shown above the zero line and outflow below the line. The outflow is the systolic ejection velocity. (A) A normal pattern of blood flow. (B) Holosystolic AV valve regurgitation (arrow), (C) SL valve regurgitation (arrow), and (D) monophasic inflow pattern with merged E and A waves (arrow). E, early ventricular filling; A, late ventricular filling during atrial contraction; ICT, isovolemic contraction time; IRT, isovolemic relaxation time; ET, ejection time. (E–J) Blood flow velocity waveforms obtained from the descending aorta (E,G,I) and umbilical artery (F,H,J) of a control embryo (E,F), a Li-exposed embryo (G,H), and an HCy-exposed embryo (I,J). The control embryo waveforms show a normal pattern with diastolic flow (E,F), whereas the Li-exposed embryo waveforms show an absence of diastolic flow (G,H). (I,J) Blood flow in the maternal uterine artery (I) and the descending aorta (J) of an HCy-exposed embryo is similiar to control animals. (K–M) Doppler velocity waveforms of blood flow on E15.5 after a single exposure to HCy on E6.75. The waveforms show SL valve regurgitation (K), SL valve stenosis (L), and AV valve regurgitation (M).

Table 3.

Comparison between maternal and embryonic hemodynamic parameters obtained by Doppler ultrasonography of mice at E15.5, after exposure at E6.75 to Li, HCy or NaCl (control)

| Maternal variables | HCy (n=59) | NaCl (n=42) | Li (n=68) | Pvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | 458 | 421 | 491 ↑ | <0.0001* |

| Uterine artery PI | 2.82 | 2.77 | 2.12 ↓ | 0.0001* |

| Embryonic variables | ||||

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | 181 | 169 | 195 ↑ | 0.0004* |

| Umbilical artery PI | 1.55 | 1.68 | 1.76 | NS |

| Ductus venosus PI | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | NS |

| Descending aorta PI | 1.99 | 1.94 | 2.11 | NS |

| ICT (%) | 6.56 | 7.27 | 7.54 | NS |

| IRT (%) | 11.93 | 12.30 | 16.82 ↑ | 0.0025* |

| ET (%) | 42.51 | 41.71 | 41.26 | NS |

| MPI | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.60 ↑ | 0.0049* |

| E velocity (cm/second) | 12.25 | 11.32 | 11.46 | NS |

| A velocity (cm/second) | 40.14 | 37.27 | 41.36 ↑ | 0.0214* |

| E/A ratio | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.27 ↓ | 0.0065* |

| OF peak velocity (cm/second) | 39.92 | 36.56 | 41.05 ↑ | 0.0476* |

All data represent median values.

Parameters showing significant values for Li when compared with the control group, as based on the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test.

PI, pulsatility index; ICT, proportion of isovolemic contraction time in the cardiac cycle; IRT, proportion of isovolemic relaxation time in the cardiac cycle; ET, proportion of the ejection time in the cardiac cycle; MPI, myocardial performance index; E, inflow velocity during early ventricular filling; A, inflow velocity during atrial contraction; OF, ventricular outflow tract.

Table 4.

Summary of FA rescue of the Li or HCy effects on mouse heart development

| Valve regurgitation | CRL (mm) | Body weight (g) | Placenta weight (g) | Resorptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCy | 39/59 (66.1%) | 13 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 27/59 (45.7%) |

| Li | 43/68 (63.2%) | 13.8 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 16/68 (23.5%) |

| NaCl | 0/42 | 15.2 | 0.41 | 0.13 | 0/42 |

| HCy + FA rescue | 0/27 | 14.8 | 0.42 | 0.12 | 0/27 |

| Li + FA rescue | 1/30 (3.3%) | 14.6 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 1/30 (3.3%) |

CRL, crown-rump length.

Li group compared with control group. Based on the median values shown in Table 3, the maternal heart rate was higher and the uterine artery pulsatility index was lower in the Li group versus the control group. With Li exposure, 63% (n=43/68) of embryos displayed valve regurgitation (Fig. 7A, normal pattern; Fig. 7B–D, abnormal pattern): semilunar (SL) valve regurgitation (Fig. 7C) occurred in 34 (50%) of the embryos, and both SL and atrioventricular (AV) valve regurgitation occurred in 9 (13%) of the embryos. The increased atrial contractility may be a compensatory mechanism, since compliance of the ventricles was reduced.

HCy group compared with control group. Except for the structural and valve defects described below, there were few statistically significant differences in myocardial performance between the HCy and control groups. Fig. 7E–M depicts the typical waveforms that were obtained. Thirty-nine (66%) embryos exposed acutely to HCy displayed valve regurgitation. SL valve regurgitation occurred in 53% of embryos, AV valve regurgitation in 10%, and both AV and SL valve regurgitation occurred in 3% of embryos. All control animals had normal Doppler patterns (Fig. 7A). In summary, cardiac valve defects developed at a similar rate in embryos following a single exposure to Li or HCy on E6.75. Based on statistically significant differences, acute Li exposure results in poorer myocardial performance than that observed with HCy.

Following echo monitoring on E15.5, placental weight and morphometric measurements of crown-rump length and body weight were obtained. With a single exposure to Li or HCy, all three morphometric measurements were significantly decreased compared with control embryos (Table 4). There were also significantly more resorptions with HCy (46%, n=27/59 embryos) than with Li exposure (24%, n=16/68 embryos). Some litters were allowed to develop to E18.5. No recovery of development was apparent and the same valve defects were seen on E18.5 (data not shown) compared with those seen earlier in gestation, indicating that it was not only a delay in valve development that was monitored on E15.5.

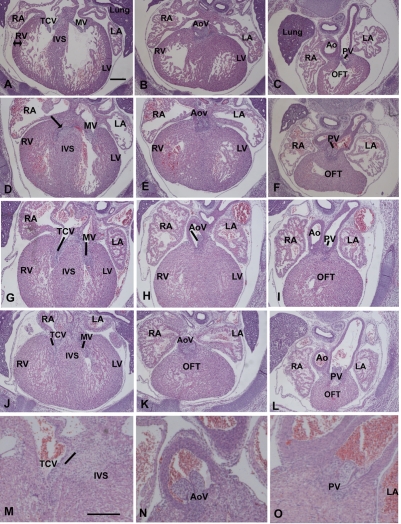

Pathological assessment of HCy-exposed embryonic hearts

On E15.5 (Fig. 8A–C, control heart), HCy exposure was associated with right and left side cardiac hypertrophy, as evidenced by an increase in myocardial wall thickness (Fig. 8D–L). The lumen often had a spongy appearance and was not distinctly evident. In embryos that displayed AV valve regurgitation upon echo monitoring, most tricuspid valve leaflets had not formed normally: the septal leaflet had not delaminated and it remained attached to a wide interventricular septum (compare the normal AV valves in Fig. 8A with the AV valve anomalies that are apparent in Fig. 8D,G). The embryo shown in Fig. 8G–I displayed an echo pattern indicating both AV and SL valve regurgitation. Malformed and small aortic valves (AoV in H) and pulmonary valves (PV in I) were apparent. The embryonic heart shown in the sections in Fig. 8J–L displayed an echo pattern that was indicative of SL valve stenosis. This was exemplified by a post-stenotic dilatation of the pulmonary artery, apparent in Fig. 8L. Fig. 8M–O shows enlargements of valve regions of hearts with abnormal echo patterns. In summary, in addition to the general cardiac hypertrophy, the viable cardiac anomalies that were observed on E15.5 following a single HCy exposure on E6.75 related primarily to derivatives of the SHF, that is the outflow, the right ventricle, and the tricuspid and SL valves.

Fig. 8.

Pathology of HCy-exposed E15.5 mouse hearts displaying abnormal echo patterns. The panels in the left column depict AV valves (TCV, tricuspid valve; MV, mitral valve); the middle column shows aortic valves (AoV); and the right column shows pulmonary valves (PV). (A–C) A control heart. (D–F) An embryo with AV valve regurgitation. (G–I) An embryo displaying SL and AV valve regurgitation upon echocardiography. (J–L) The echo patterns for this embryo defined pulmonary stenosis. (M–O) Higher magnification of valves in hearts showing valve regurgitation upon echocardiography of an AV valve (M) and SL valves (N,O). RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle, LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; IVS, interventricular septum; Ao, aorta; OFT, outflow tract. In all panels, the embryonic anterior is to the top. Bars, 152 μm.

FA supplementation results in normal cardiac function in Li- and HCy-exposed mouse embryos

We next determined whether rescue of normal cardiac function and valve defects is possible using FA supplementation with Li or elevated HCy exposure. Pregnant females were administered concomitantly with FA (125 μl at 75 μM) and HCy (75 μM), both intraperitoneally (i.p.), on E6.75. FA supplementation resulted in normal valve development and cardiac function, as determined by echocardiography in the HCy-exposed group (100%, n=27/27 embryos). However, FA supplementation provided on E6.75 normalized the effects of HCy, but not Li, exposure. Protection from Li exposure was obtained when FA was administered in the diet at 10 mg/kg throughout gestation, beginning with the presence of the vaginal plug on the morning of E0.5. Cardiac development then remained protected following Li exposure on E6.75. Normal valve formation and cardiac function were observed in 40 out of 41 embryos monitored (97.6%) (Table 4). The one embryo that did not have a normal echo pattern displayed mild SL valve regurgitation. In summary, FA rescued cardiac function in the mouse embryo after acute Li or HCy exposure; however, Li-induced defects required earlier and higher levels of FA supplementation for rescue.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that Li and elevated HCy pose a serious threat to embryonic heart development, and that heart defects can be induced by only a single exposure during gastrulation and cardiac specification. In the early embryo, Wnt–β-catenin signaling in the cardiogenic crescent is required to maintain the undifferentiated state of cells. A key downstream intermediary of the active pathway is β-catenin, which accumulates in the cytoplasm and translocates to the nucleus to activate target genes. Preceding specification, the mesendoderm of the bilateral heart fields begins to express the Wnt antagonists Crescent and Dickkopf-1 (Dkk-1). These antagonists suppress canonical Wnt signaling, resulting in decreased β-catenin levels. As a result, genes associated with the induction of cardiogenesis, such as Hex and Isl1, are upregulated. Hex is expressed in the prechordal plate and primary heart field and Islet-1, a marker for the SHF, is synthesized (Cohen et al., 2007; Foley and Mercola, 2005). Both Li and HCy act to augment canonical Wnt signaling intracellularly, and are able to bypass the extracellular Dkk-1 or Crescent antagonism. Therefore, both Li and HCy exposure cause the Wnt–β-catenin pathway to remain active at a time when it would normally be downregulated in the early embryo. Thus, Li and HCy repress and delay the induction of Hex and Islet-1.

An association between HCy and FA deficiency and the Wnt–β-catenin pathway has been suggested previously from microarray analysis (Ernest et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007). Additionally, analysis of tumorigenesis indicates that histone and DNA methylation are fundamental processes in the Wnt–β-catenin pathway and in gene target regulation (Sierra et al., 2006; Wohrle et al., 2007), including by β-catenin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and Dkk-1 regulation (Csepregi et al., 2007; Willert and Jones, 2006). HCy and FA are central molecules in the synthesis path for S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor for biological methylation. FA deficiency causes HCy accumulation and produces a cellular deficit of SAM, thus limiting transmethylation reactions in the nucleus (Williams and Schalinske, 2007). Since β-catenin/lymphoid-enhancer factor (LEF) also regulates Isl1 expression (Lin et al., 2007), we suggest that elevated HCy may, through an epigenetic mechanism involving methylation, modulate the Wnt–β-catenin pathway and its target gene expression. As a corollary, FA rescue of the effects of Li and Wnt3A could be either at the level of methylation of β-catenin nuclear-binding proteins and/or at the level of DNA methylation, which affects the expression and synthesis of the antagonist Dkk-1. Either possibility can lead to potentiation of β-catenin target genes.

Li action starts in the cytoplasm but, through β-catenin, it also has a nuclear effect on gene expression. Li potentiates Wnt–β-catenin signaling by inhibiting GSK-3 and thereby stabilizing cytoplasmic β-catenin. In addition, Li suppresses the inositol-signaling pathway by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase and inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase (Belmaker et al., 1998). Wnt3A triggers G-protein-linked phosphatidylinositol signaling, transiently generating inositol polyphosphates, including inositol pentakisphosphate (IP5, also known as Ins(1,3,4,5,6)P5). IP5, in turn, inhibits GSK-3β activity (Gao and Wang, 2007). Blocking IP5 formation blocks β-catenin accumulation (Gao and Wang, 2007). Excess inositol may decrease IP5 formation by increasing the generation of di- and tri-polyphosphates. The association between the inositol phosphatidyl pathway and its intermediates with canonical Wnt signaling would explain the level of severity and the varied phenotypic cardiac defects that are induced by Li exposure in comparison with HCy. The additive effect of myoinositol and FA in protection from Li exposure suggests the involvement of this second messenger pathway in Wnt signaling. We propose that the FA effect occurs primarily at the nuclear level by protecting transmethylation reactions and by replenishing nucleotide pools, whereas the inositol effect is cytoplasmic, involving inositol polyphosphate signaling. As a result, the protective effects of FA and myoinositol are additive.

In addition to the cardiac hypertrophy, the viable cardiac valve anomalies seen on E15.5 following a single HCy exposure on E6.75 are related primarily to derivatives of the SHF (i.e. the outflow, the right ventricle, and the tricuspid and SL valves). In the embryonic heart, the valves are derived from the endocardial cushions, including in the outflow (Anderson et al., 2003). Expression of Isl1, a marker for the SHF, is suppressed for a time period by a pulse of Li or HCy, suggesting that the tricuspid and SL valve structures are affected downstream because these structures are derivatives of the right ventricle and outflow, respectively. Published evidence, using regulatory elements from the mouse Mef2c gene to direct the expression of Cre recombinase exclusively in the anterior heart field (AHF) and in its derivatives, indicates that the AHF enhancer is active in the future right ventricle, which includes the tricuspid valve region, and in the outflow tract, including the pulmonary valve (Verzi et al., 2005). Verzi et al. also reported that the endocardial endothelial cells of the right ventricle and outflow tract, which contribute to cushion formation, are marked by the Mef2c-AHF-Cre transgene. This cell lineage analysis showed that near the base of the heart, both Wnt1-Cre- and Mef2c-AHF-Cre-derived cells contributed to the smooth muscle cells of the pulmonary trunk and to the cells of the pulmonary valve leaflets. Wnt signaling plays an important role in controlling endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and in proliferation of the endocardial cushion cells. Therefore, early exposure to Li and HCy apparently affects cells that are later modulated by Wnt signaling in the endocardial cushion during valve formation. We suggested previously that some of these cells in the endocardial cushions are derived from the prechordal plate that arises from cells at the embryonic midline during gastrulation (Chen et al., 2008; Seifert et al., 1993). Other cell types may also contribute in a cell-autonomous or non-cell-autonomous manner.

The anterior-to-posterior nature of development and the specification of the first and second (anterior) heart fields are both crucial to understanding how the timing of a single-pulse exposure can vary the severity and nature of the defects. The first heart field and Hex appear to be induced slightly ahead of Islet-1. In the mouse model, we observed a great number of right ventricular, AV and SL valve defects. This suggests that, in the viable embryos on E15.5, exposure at ~E6.75 targets SHF specification over that of the first heart field. With earlier exposure we observe a high number of resorbed mouse embryos, indicating lethal effects; or, as in the avian model, no or limited areas of bilateral cardiac tissue were apparent (Manisastry et al., 2006). We also noted that HCy- and Li-induced valve defects can be phenotypically subtle and may be missed by routine histological evaluation. The defects may relate only to differences in cell numbers that populate endocardial cushion regions. Thus, the echo data was essential to determine whether valve integrity had been functionally compromised and provided information on placental blood flow that related to the intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) that we observed. IUGR is associated generally with effects on placental and heart development (Corstius et al., 2005; Morrison et al., 2007). Other studies have reported that Wnt–β-catenin signaling and HCy impact placental development (Kamudhamas et al., 2004; Mohamed et al., 2008); our results substantiate these observations. It was also evident that embryos within a litter are not all at the same stage of development, an observation that explains the variability and severity of heart defects, as, for example, observed with Ebstein’s anomaly in the human population. Cardiac development relates to the timing of a single exposure, the exposure dose, and the developmental stage of a specific embryo within the relatively narrow window of early gestation.

Patterning of the embryo and cell specification events are activated by a few evolutionarily conserved pathways, one of which is the Wnt–β-catenin pathway. These signaling proteins are used repeatedly during development and in diverse regions to regulate cell fate decisions, cell proliferation and cell migration in the embryo (Clevers, 2006). Besides cardiac development (Foley and Mercola, 2004; Kwon et al., 2007; Linask et al., 1997; Manisastry et al., 2006; Ueno et al., 2007), canonical Wnt signaling is important for neural development (Alvarez-Medina et al., 2008; Louvi et al., 2007; Ulloa and Briscoe, 2007; Yu et al., 2008) and neural crest specification and differentiation (Garcia-Castro et al., 2002; Schmidt et al., 2008). Our results may have implications for the adverse effects of Li and HCy on neurogenesis and the neural crest, and may have similar implications for FA protection as well. Additionally, Wnt–β-catenin signaling may be a target for other environmental factors that induce cardiac and neural birth defects, for example alcohol (ethanol). Since epigenetic processes are sensitive to change, they represent excellent targets to explain how environmental factors modify the gene expression of key early signaling pathways, such as the Wnt pathway, and thus how they contribute to birth defects.

METHODS

Vertebrate models and dose

Chick embryos

Pathogen-free White Leghorn chick (Gallus gallus; Charles River, MA) and quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica; Strickland Farms, GA) embryos were used to analyze the effects of HCy on early embryogenesis. The early processes of heart development are well conserved among vertebrates and the avian model allows for more precise timing of exposure in early embryos. The incubation methodology using agarose-albumin has been described previously (Darnell and Schoenwolf, 2000). Briefly, the experimental paradigm involved exposing specific early stages of chick embryos, at HH stages 4 to 7 (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951), to different concentrations of HCy (L-homocysteine thiolactone hydrochloride, Sigma) made up in physiological saline. Final concentrations of HCy included 30 μM, 50 μM, 75 μM and 100 μM. The minimal teratogenic dose was determined empirically to be 50 μM. This fitted within the concentration range of 30 μM to 300 μM used by others that induced heart defects at later stages of development (Boot et al., 2004). Control embryos were incubated using the vehicle, physiological saline, in the agarose-albumin medium. Control and experimental cultures were incubated on the agarose-albumin plates for either 8 or 24 hours.

Carrier-free, recombinant mouse Wnt3A was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). We empirically tested Wnt3A concentrations to find those that would induce cardiac defects but maintain embryonic viability. Wnt3A was tested at concentrations of 2 ng, 10 ng, 20 ng, 50 ng and 100 ng per ml. Concentrations of 2 ng/ml and 10 ng/ml were both effective in inducing cardiac defects. Both Wnt3A concentrations were used in the FA rescue experiments, as described. For the FA rescue experiments, folate (folic acid, Sigma-Aldrich) was added at a concentration of 2 μg, 5 μg or 10 μg per ml. In subsequent experiments, we used 10 μg/ml FA, which consistently rescued the heart defects induced by Li, HCy or Wnt3A in the avian model. For the experiments using inositol (myoinositol, Sigma) supplementation, a concentration of 50 mg/ml was used.

In situ hybridization. In situ hybridizations on control and experimentally manipulated chick embryos were carried out using digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes with alkaline phosphatase detection (Linask et al., 2001). Images of whole-mounted chick embryos were taken with a Nikon DS-L2 camera unit. Probes for chick Hex were provided by Parker Antin, University of Arizona and probes for chick Islet-1 (Isl1) were provided by Thomas Jessell, Columbia University, NY.

Mice

All mice were maintained according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of South Florida. The C57BL/6 mouse strain (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) was used throughout this study. E0.5 was defined as the morning when the vaginal sperm plug was detected. Timed pregnant mice were randomly allocated to receive a single dose of 100 μl of 6.25 mg/ml Li chloride, as determined previously (Chen et al., 2008), 100 μl of 75 μM HCy, or 100 μl of 6.25 mg/ml sodium chloride (control group); all treatments were given i.p. On E15.5, the utero-placental circulation of the pregnant mice, and the central and peripheral circulations of the embryos were examined non-invasively in utero using Doppler ultrasonography (Gui et al., 1996; Linask and Huhta, 2000). Sixty-eight embryos were exposed to Li, 59 to HCy and 42 to physiological saline.

An HCy concentration of 75 μM, used for maternal exposure, was determined empirically using different doses of HCy (i.e. 150, 75, 50 and 15 μM). The minimal teratogenic dose was determined to be 75 μM. An acute, single dose of HCy at E5.5 resulted in embryonic lethality (79% of embryos; there were 11 resorptions and 3 small, but viable, embryos). The single i.p. injection of HCy at E6.75 produced a high number of valve defects (66%), as well as resorptions (46%). An i.p. injection on E7.75 did not cause any valve defects (n=16). Because not all embryos within litters are at exactly the same stage of development, the variability of effects seen with either Li or HCy probably reflects the differences in developmental stage. Hence, the variable effects that were observed on heart and valve development were expected.

FA diet for rescue of cardiac defects in mouse embryos

We supplemented animal chow with 10.5 mg/kg of FA, which was the concentration used in trial human population studies. As a control diet (i.e. normal mouse chow), mice continued to receive 3.3 mg/kg of FA as the baseline to maintain the health of the female mice. The baseline supplementation does not rescue cardiac defects. The animal chow supplemented with 10.5 mg/kg of FA was prepared for us by Harlan Laboratories. As recommended by Harlan, our calculations for the FA level in the special diet are based on the metabolic body weight of mice. Because of the obvious large difference in body weight between humans and mice, and because of the large difference in metabolic rate, Harlan use the metabolic weight as a method of scaling these differences between species; for mice this was calculated to be BW0.75 (i.e. metabolic weight equals body weight to the 0.75 power). Each mouse consumes approximately 4 g of chow per day; therefore, to obtain the desired dose of 10.5 mg/kg, we added 7.2 mg/kg of FA to the normal 3.3 mg/kg that is present in commercial chow. Pregnant mice were divided randomly into the experimental group that was supplemented with 10.5 mg/kg of FA and the control group of mice that did not receive any additional FA. On the morning of the plug date (E0.5), the pregnant mice were placed on the defined Harlan chows and maintained on this diet throughout the study. On E6.75 (at 15:30 PM) all pregnant females received Li (6.25 mg/125 μl), by an i.p. injection, which consistently induced valve and heart defects, as detected by echo on E15.5.

Doppler ultrasonography

Doppler ultrasonographic examinations were carried out using the Philips Sonos 5500 (Andover, MA) with a 12 MHz transducer and, more recently, with a Vevo 770 (VisualSonics) system. Both instruments provided similar echo patterns. On E15.5, the pregnant mice were anesthetized using a Surgivet Tech 4 anesthesia system (Waukesha, WI) with inhalation anesthesia, consisting of 3% isoflurane, administered through a nose cone; the mice were then maintained on 1% isoflurane with 21% oxygen. The mother was placed supine on a heating pad with electrode footpads. The heart rate and temperature of the pregnant mice were monitored using a THM100 (Indus Instruments, Houston, TX) during scanning. The body temperature was maintained at 37°C.

Maternal uterine artery blood flow velocity waveforms were obtained and the pulsatility index was calculated. The embryos were visualized and their position mapped in each uterine horn. Blood flow in the heart and blood vessels was detected in each embryo using color Doppler, and blood flow velocity waveforms were obtained using pulsed wave Doppler. Once the embryonic heart was identified by color Doppler, the sample volume of the pulsed Doppler was placed over the entire heart to obtain blood velocities. The gate length was adjusted to completely insonate the beating embryonic heart. The high-pass filter was at its lowest setting of 50 Hz. The embryonic heart was examined from several angles of insonation to obtain the maximal velocities and inflow and outflow waveforms. The pulsatility index was calculated from the descending aorta, umbilical artery and ductus venosus blood flow velocity waveforms. The cardiac cycle time intervals were measured from the inflow-outflow velocity waveforms, and the index of global myocardial performance (Tei index) was calculated as: (ICT+IRT)/ET, where ICT is the isovolemic contraction time, IRT is the isovolemic relaxation time and ET is the ejection time (Fig. 7). The presence of any valvular regurgitation was recorded. Holosystolic AV valve regurgitation was defined as regurgitation that occurred from the closure to the opening of the AV valve and with a peak velocity higher than 50 cm/second. SL valve regurgitation was identified as the diastolic blood velocity waveform that is usually superimposed on the inflow waveforms. During echo, although the diastolic regurgitation jet of the SL valve is usually superimposed on the inflow waveform, by manipulating the ultrasound transducer and sample volume of the Doppler gate it is possible to obtain the inflow waveforms in the same Doppler envelope, thus allowing the measurement of IRT. After the ultrasonographic examination, the female mouse was euthanized and the fetuses within the uterine horns were identified according to their location during the ultrasonographic examination. The embryos were removed and processed for paraffin sectioning.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.1 (Cary, NC). We tested whether there was any significant difference among the three groups (global test) using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. If the global test indicated that a significant difference existed, pair-wise comparisons were carried out to test which pair(s) had a significant difference, again using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Three possible pairs were analyzed: control versus HCy, control versus Li, and Li versus HCy. The significant differences are highlighted in Table 3. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Histology and microscopy

Li- and HCy-exposed embryos, and control NaCl-exposed embryos, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and paraffin sectioned. Sections were stained with hematoxylineosin, and some were stained with Toluidine Blue, and examined. Cardiac regions were analyzed for the presence of any obvious malformations using a Nikon SMZ1500 fluorescent stereomicroscope, and digitized images were obtained using a Nikon DS-L2 camera unit.

Acknowledgments

Support from NIH R01 grant HL 67306 (to K.K.L.), American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid (to K.K.L.) and Suncoast Cardiovascular Research and Education Foundation, founded by Helen Harper Brown (to K.K.L.); and partial support from the Mason Chair (to K.K.L.) and the Daicoff-Andrews Chair in Perinatal Cardiology (to J.C.H.) from the Foundation of the University of South Florida, College of Medicine and All Children’s Hospital are acknowledged. We thank Jane Carver, USF Department of Pediatrics, for editing the manuscript. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.H. carried out chick embryo analysis of HCy exposure; the in situ hybridization analysis of Hex and Isl1 gene expression; and mouse histology. M.C.S. carried out the Doppler ultrasound studies of embryonic mouse heart function; chick embryo analysis of HCy exposure and mouse FA rescue; and aided in manuscript preparation. R.L.-V. was involved with avian Wnt3A and FA rescue experiments. P.B. carried out the pathological analysis of HCy-exposed embryonic mouse hearts, and avian FA and FA/inositol rescue experiments. R.C. did the statistical analysis of echo data. J.C.H. and G.A. aided with interpretations of ultrasound patterns and edited the manuscript. K.K.L. developed the concepts and approach for these studies; integrated the various parts of the analyses; coordinated data acquisition; and prepared the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Ai D, Fu X, Wang J, Lu MF, Chen L, Baldini A, Klein WH, Martin JF. (2007). Canonical Wnt signaling functions in second heart field to promote right ventricular growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 9319–9324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Medina R, Cayuso J, Okubo T, Takada S, Marti E. (2008). Wnt canonical pathway restricts graded Shh/Gli patterning activity through the regulation of Gli3 expression. Development 135, 237–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RH, Webb S, Brown NA, Lamers WH, Moorman A. (2003). Development of the Heart: (3) formation of the ventricular outflow tracts, arterial valves, and intrapericardial arterial trunks. Heart 89, 1110–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmaker RH, Agam G, van Calker D, Richards MH, Kofman O. (1998). Behavioral reversal of lithium effects by four inositol isomers correlates perfectly with biochemical effects on the PI cycle. Neuropsychopharmacology 19, 220–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot MJ, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Poelmann RE, van Iperen L, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. (2004). Cardiac outflow tract malformations in chick embryos exposed to homocysteine. Cardiovasc Res. 64, 365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai CL, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu PH, Pfaff SL, Chen J, Evans S. (2003). Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev Cell 5, 877–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Han M, Manisastry SM, Trotta P, Serrano MC, Huhta JC, Linask KK. (2008). Molecular effects of lithium exposure during mouse and chick gastrulation and subsequent valve dysmorphogenesis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 82, 508–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H. (2006). Wnt/B-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127, 469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ED, Wang Z, Lepore JJ, Lu MM, Taketo MM, Epstein DJ, Morrisey EE. (2007). Wnt/beta-catenin signaling promotes expansion of Isl-1-positive cardiac progenitor cells through regulation of FGF signaling. J Clin Invest. 117, 1794–1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Friedman JM, Jefferson JW, Johnson EM, Weiner ML. (1994). A reevaluation of risk of in utero exposure to lithium. JAMA 271, 146–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corstius H, Zimanyi MA, Maka N, Herath T, Thomas W, Van der Laarse A, Wreford NG, Black MJ. (2005). Effect of intrauterine growth restriction on the number of cardiomyocytes in rat hearts. Pediatr Res. 57, 796–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csepregi A, Rocken C, Hoffmann J, Gu P, Saliger S, Muller O, Schneider-Stock R, Kutzner N, Roessner A, Malfertheiner P, et al. (2007). APC promoter methylation and protein expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 134, 579–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell DK, Schoenwolf GC. (2000). Culture of avian embryos. In Developmental Biology Protocols, vol. 1 (ed. Tuan RS, Lo CW.), pp. 31–38 Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz MV, Sanchez-Gomez C, Palomina MA. (1989). The primitive cardiac regions in the straight tube heart (Stage 9-) and their anatomical expression in the mature heart: an experimental study in the chick embryo. J Anat. 165, 121–131 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz MV, Sanchez Gomez C, Cayre R. (1991). The developmental components of the ventricles: their significance in congenital cardiac malformations. Cardiol Young 1, 123–128 [Google Scholar]

- Ernest S, Carter M, Shao H, Hosack A, Lerner N, Colmenares C, Rosenblatt DS, Pao YH, Ross ME, Nadeau JH. (2006). Parallel changes in metabolite and expression profiles in crooked-tail mutant and folate-reduced wild-type mice. Hum Mol Genet. 15, 3387–3393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley A, Mercola M. (2004). Heart induction: embryology to cardiomyocyte regeneration. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 14, 121–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley AC, Mercola M. (2005). Heart induction by Wnt antagonists depends on the homeodomain transcription factor Hex. Genes Dev. 19, 387–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Wang HY. (2007). Inositol pentakisphosphate mediates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Biol Chem. 282, 26490–26502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Castro MI, Marcelle C, Bronner-Fraser M. (2002). Ectodermal Wnt function as a neural crest inducer. Science 297, 848–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui YH, Linask KK, Khowsathit P, Huhta JC. (1996). Doppler echocardiography of normal and abnormal embryonic mouse heart. Pediatr Res. 40, 633–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. (1951). A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J Morphol. 88, 49–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhta JC, Linask K, Bailey L. (2006). Recent advances in the prevention of congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 18, 484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlstone AF, Haramis AP, Wienholds E, Begthel H, Korving J, Van Eeden F, Cuppen E, Zivkovic D, Plasterk RH, Clevers H. (2003). The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway regulates cardiac valve formation. Nature 425, 633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal M, Mahmud S. (2001). The effects of lithium, valproic acid, and carbamazepine during pregnancy and lactation. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 39, 381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson S, Ceolin L, Kaur P, Pastuszak A, Einarson T, Koren G, Jones K, Johnson KSD, Donnenfeld AE, Rieder M, et al. (1992). Prospective multicentre study of pregnancy outcome after lithium exposure during first trimester. Lancet 339, 530–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamudhamas A, Pang L, Smith SD, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM. (2004). Homocysteine thiolactone induces apoptosis in cultured human trophoblasts: A mechanism for homocysteine-mediated placental dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 191, 563–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein PS, Melton DA. (1996). A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 8455–8459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon C, Arnold J, Hsiao EC, Taketo MM, Conklin BR, Srivastava D. (2007). Canonical Wnt signaling is a positive regulator of mammalian cardiac progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 10894–10899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Cui L, Zhou W, Dufort D, Zhang X, Cai CL, Bu L, Yang L, Martin J, Kemler R, et al. (2007). Beta-catenin directly regulates Islet1 expression in cardiovascular progenitors and is required for multiple aspects of cardiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 9313–9318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linask KK. (1992). N-cadherin localization in early heart development and polar expression of Na+,K(+)-ATPase, and integrin during pericardial coelom formation and epithelialization of the differentiating myocardium. Dev Biol. 151, 213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linask KK, Huhta JC. (2000). Use of doppler echocardiography to monitor embryonic mouse heart function. Dev Biol Protoc. 1, 245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linask KK, Knudsen KA, Gui YH. (1997). N-cadherin-catenin interaction: necessary component of cardiac cell compartmentalization during early vertebrate heart development. Dev Biol. 185, 148–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linask KK, Han MD, Artman M, Ludwig CA. (2001). Sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX-1) and calcium modulation. NCX protein expression patterns and regulation of early heart development. Dev Dyn. 221, 249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Choi SW, Crott JW, Keyes MK, Jang H, Smith DE, Kim M, Laird PW, Bronson R, Mason JB. (2007). Mild depletion of dietary folate combined with other B vitamins alters multiple components of the Wnt pathway in mouse colon. J Nutr. 137, 2701–2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvi A, Yoshida M, Grove EA. (2007). The derivatives of the Wnt3a lineage in the central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 504, 550–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manisastry SM, Han M, Linask KK. (2006). Early temporal-specific responses and differential sensitivity to lithium and Wnt-3A exposure during heart development. Dev Dyn. 235, 2160–2174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed OA, Jonnaert M, Labelle-Dumais C, Kuroda K, Clarke HJ, Dufort D. (2008). Uterine Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is required for implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 8579–8584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JL, Botting KJ, Dyer JL, Williams SJ, Thornburg KL, McMillen IC. (2007). Restriction of placental function alters heart development in the sheep fetus. Am J Physiol Integr Comp Physiol. 293, R306–R313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MM, Wright HV, Asling W, Evans HM. (1955). Multiple congenital abnormalities resulting from transitory deficiency of pteroylglutamic acid during gestation in the rat. J Nutr. 56, 349–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist TH, Finnell RH. (2001). Genes, folate and homocysteine in embryonic development. Proc Nutr Soc. 60, 53–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist TH, Ratashak SA, Selhub J. (1996). Homocysteine induces congenital defects of the heart and neural tube: effect of folic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 15227–15232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C, McGonnell I, Allen S, Patel K. (2008). The role of Wnt signalling in the development of somites and neural crest. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 195, 1–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert R, Jacob M, Jacob HJ. (1993). The avian prechordal head region: a morphological study. J Anat. 183, 75–89 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J, Yoshida T, Joazeiro CA, Jones KA. (2006). The APC tumor suppressor counteracts beta-catenin activation and H3K4 methylation at Wnt target genes. Genes Dev. 20, 586–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithberg M, Dixit P. (1982). Teratogenic effects of lithium in mice. Teratology 26, 239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LS, Wlodarczyk BJ, Santillano DR, Miranda RC, Finnell RH. (2004). Developmental consequences of abnormal folate transport during murine heart morphogenesis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 70, 449–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Weidinger G, Osugi T, Kohn AD, Golob JL, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Moon RT, Murry CE. (2007). Biphasic role for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiac specification in zebrafish and embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 6685–9690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa F, Briscoe J. (2007). Morphogens and the control of cell proliferation and patterning in the spinal cord. Cell Cycle 6, 2640–2649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verzi MP, McCulley DJ, De Val S, Dodou E, Black BL. (2005). The right ventricle, outflow tract, and ventricular septum comprise a restricted expression domain within the secondary/anterior heart field. Dev Biol. 287, 134–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K, Jones K. (2006). Wnt signaling: is the party in the nucleus? Genes Dev. 20, 1394–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KT, Schalinske KL. (2007). New insights into the regulation of methyl group and homocysteine metabolism. J Nutr. 137, 311–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohrle S, Wallmen B, Hecht A. (2007). Differential control of Wnt target genes involves epigenetic mechanisms and selective promoter occupancy by T-cell factors. Mol Cell Biol. 27, 8164–8177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Stowe Z, Leibenluft E, Cohen L, Miller L, Manber R, Viguera A, Suppes T, Altshuler L. (2004). Management of bipolar disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Am J Psychiatry 161, 608–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, McDonnell K, Taketo MM, Bai CB. (2008). Wnt signaling determines ventral spinal cord cell fates in a time-dependent manner. Development 135, 3687–3696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Phiel C, Spece L, Gurvich N, Klein P. (2003). Inhibitory phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) in response to lithium. J Biol Chem. 278, 33067–33077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Wlodarczyk BJ, Scott M, Yu W, Merriweather M, Gelineau-van Waes J, Schwartz RJ, Finnell RH. (2007). Cardiovascular abnormalities in Folr1 knockout mice and folate rescue. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 79, 257–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]