Abstract

The transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) has been shown to regulate an animal’s behavioral responsiveness to emotionally-salient stimuli, and an increase in CREB phosphorylation in the NAc has been observed during exposure to rewarding stimuli, such as drugs of abuse. Here we show that CREB phosphorylation also increases in the NAc during exposure to cues that an animal has associated with delivery of natural rewards. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (rattus norvegicus) were trained to associate an auditory stimulus with delivery of food pellets, and CREB phosphorylation was examined in the striatum following training. We found that repeated tone-food pairings resulted in an increase in CREB phosphorylation in the NAc but not in the adjacent dorsal striatum or in the NAc 3 hr after the final training session. We further found that the cue itself, as opposed to the food pellets, the training context, or tone-food pairings, was sufficient to increase CREB phosphorylation in the NAc. These results suggest that the processing of primary rewarding stimuli and of environmental cues that predict them triggers similar accumbal signaling mechanisms.

Keywords: reward, striatum, approach, associative, conditioning

The nucleus accumbens (NAc) regulates behavioral responses to both emotionally salient stimuli and to cues and contexts that predict such stimuli (Cardinal et al., 2002; Kelley et al., 2005). Exposure to emotionally salient stimuli and drugs of abuse increase phosphorylation of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in the NAc (Barrot et al., 2002; Walters et al., 2005). Furthermore, alteration of CREB signaling within the NAc alters behavioral responses to these stimuli and to drugs of abuse (Carlezon et al., 1998; Pliakas et al., 2001; Walters and Blendy, 2001; Barrot et al., 2002).

Previous research showed that exposure to contextual cues that were paired with drugs of abuse increases CREB phosphorylation in the NAc (Miller and Marshall, 2005; Kuo et al., 2007; Tropea et al., 2008). However, these results might reflect a neuroadaptation to repeated drug exposure in that repeated drug exposure may have caused CREB phosphorylation to become sensitive to reward-associated cues. It is not known whether an increase in CREB phosphorylation occurs in the NAc during exposure to cues associated with natural rewards in the absence of drug-induced neuroadaptations. Such information would be valuable in determining the extent to which natural reward-learning mechanisms are recruited in addiction. To address this question, we used Pavlovian conditioning to train rats to associate a conditioned stimulus (CS) with delivery of food reward, and then measured CREB phosphorylation in the NAc after different amounts of Pavlovian training and after CS presentation. We hypothesized that if CREB phosphorylation in the NAc has a role in shaping behavioral responses to CS’s, then CS presentation should result in increased CREB phosphorylation within the NAc.

We placed male Sprague-Dawley rats (Hilltop Lab Animals, Scottdale, PA) on a restricted diet of about 20 g of rat chow per day to maintain their body weight at approximately 90% of their free-feeding weight. Animals were trained in standard operant chambers (Med-Associates, St. Albans, Vermont) to associate a 90-sec tone (3-KHz, 80-db) with delivery of 3 45-mg sucrose pellets (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) into a food cup within the operant chamber. Each daily training session consisted of 8 tone presentations with a 4.5- to 6.5-min inter-trial interval. Rats assigned to the control group were presented with an identical number of tones; however, food pellets were never delivered during the session. All animal procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The behavioral data were collected in the Rodent Behavior Analysis Core of the University of Pittsburgh.

During each training session the number of head entries to the food cup was recorded during the first 30 sec of the tone presentation (i.e., before delivery of pellets) and during the 30 sec preceding tone onset. Rats displayed significantly greater discriminated food cup approach (tone minus pre-tone head insertions) during the fourth conditioning session compared to control rats and to trained rats during the first training session (two-way ANOVA: effect of training F1, 27 = 8.73; training x session interaction: F1,27 = 5.23, all p’s < 0.05; independent samples t-test: 4 sessions versus control, t18 = 3.73, p< 0.01; 4 sessions versus 1 session, t17 = 2.30, p < 0.05) (Figure 1 A). These data were part of a dataset described previously (Shiflett et al., 2008).

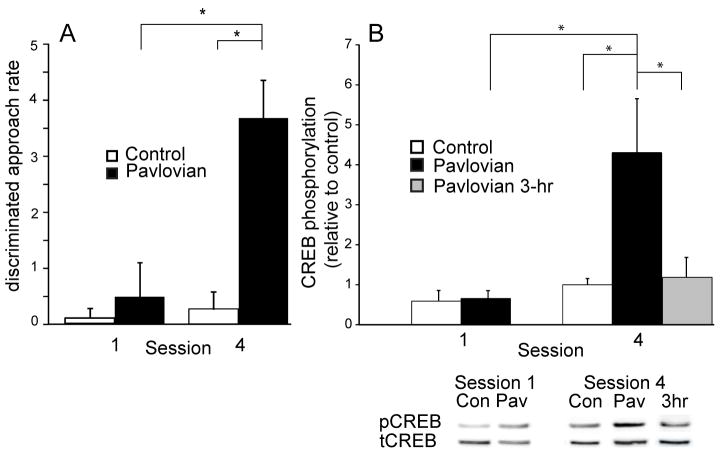

Figure 1.

Repeated appetitive Pavlovian conditioning increases Ser133-phosphorylation of CREB in the NAc. Panel A: discriminated food-cup approach (tone minus pre-tone head insertions) was measured in rats that underwent either 1 Pavlovian conditioning session or 4 Pavlovian conditioning sessions (black bars) or served as controls that experienced unrewarded tone presentations for either 1 session or 4 sessions (white bars). Discriminated food-cup approach was significantly greater in trained rats during the fourth training session (n = 14), compared to the performance of rats that experienced a single training session (n = 5) or of control rats that were presented with four sessions of unrewarded tones (n = 6). Panel B: CREB phosphorylation (normalized ratio of phospho-CREB immunoreactivity to total CREB immunoreactivity, expressed relative to the control group) was determined for NAc samples from Pavlovian trained rats and control rats after completion of either the first or the fourth training session. A significant increase in CREB phosphorylation was observed in NAc samples harvested from trained rats immediately after the fourth training session (n=6), compared to the level of CREB phosphorylation in NAc samples from control rats (n=6), trained rats that received a single training session (n=5), or trained rats 3 hr after the fourth training session (gray bar; n = 8). Representative immunoblots are shown for both phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) and total CREB (phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated; tCREB) from NAc samples taken either immediately after (Pav) or 3 hr after Pavlovian training (3 hr), or from control samples (con). * = significantly different at p < 0.05. Error bars equal ± 1 SEM.

To measure CREB phosphorylation in the NAc and the dorsal striatum, rats were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (300 mg/kg i.p.) immediately following the training session, and their brains were removed and rapidly frozen in chilled isopentane. Tissue samples from the NAc and the dorsal striatum were examined for CREB phosphorylation using methods described previously (Thiels et al., 2002). Briefly, samples were dissociated in homogenization buffer to a uniform protein concentration, resolved via SDS-PAGE, and then blotted electrophoretically to an Immobilon membrane for probing with an antibody that selectively recognizes S133-phosphorylated CREB (pCREB; 1:1000 dilution; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Antigen binding was visualized with an HRP-linked secondary antibody (Anti-Rabbit, 1:5000; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) and an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Lumiglo, Cell Signaling). The membranes were stripped of their antigens and re-probed with an antibody that specifically recognizes total (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated CREB; tCREB; 1:1000, Upstate/Millipore, Burlington, MA) using the same methods as described above. In some cases, membranes were re-probed with an antibody that specifically recognizes LDH (1:2000; Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA), to control for potential differences in protein loading. Blot images were captured with a CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) and analyzed using densitometry software (UVP Labworks, Upland, CA).

We found significantly greater CREB phosphorylation (pCREB/tCREB immunoreactivity) in NAc samples taken immediately after the fourth training session compared to CREB phosphorylation in samples from the corresponding control group or from samples taken after the first training session (two-way ANOVA: effect of training session, F1, 19 = 6.61; effect of group, F1,19 = 7.84; group x session interaction, F1,19 = 4.73, p’s < 0.05; independent samples t-test: 4 sessions versus control, t10 = 2.90; 4 sessions versus 1 session, t9 = 2.54, both p’s < 0.05) (Figure 1 B). CREB phosphorylation in samples taken 3 hr after the fourth training session was similar to control samples and lower than that observed immediately after the fourth training session (independent samples t-test: Pavlovian versus 3-hr, t12 = 2.29, p < 0.05) (Figure 1 B). In contrast to the NAc, CREB phosphorylation in the dorsal striatum revealed no differential effect of Pavlovian training (p’s > 0.1; data not shown). Furthermore, no treatment effects were observed on tCREB levels (p’s > 0.1). Therefore, the observed increase in CREB phosphorylation in the NAc after repeated training appears to reflect an increase in the level of phosphorylated CREB, rather than a treatment-related decrease in total CREB. Overall, these data indicate that repeated Pavlovian conditioning increases CREB phosphorylation specifically within the NAc, and that this increase in CREB phosphorylation occurs during and/or immediately after conditioning.

We next examined whether the CS itself was sufficient to increase CREB phosphorylation in the NAc. Rats that previously underwent 4 Pavlovian conditioning sessions were placed in the operant chamber and presented with either the tone or the context only (no tones were presented). Neither group received food pellets. The pattern of approach to the food cup during the test differed between the two groups; rats presented with the tone made significantly more head insertions during the tone than the pre-tone period, whereas rats presented with only the context distributed their approach responses equally across the test session (two-way ANOVA: effect of interval (tone or pre-tone): F1, 9 = 11.23, group (tone or context) x interval interaction: F1, 9 = 9.97, both p’s < 0.05; paired t-test, tone group, t5 = 2.61, p < 0.05; context group, p > 0.1) (Figure 2 A). These data were part of a dataset described previously (Shiflett et al., 2008).

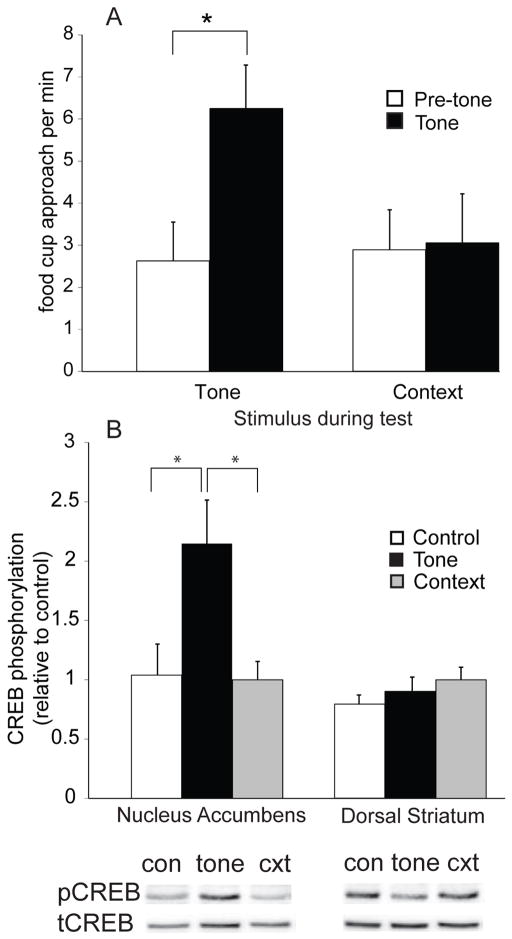

Figure 2.

Exposure to a reward-associated stimulus evokes increased CREB phosphorylation in the NAc. Panel A: rats that underwent Pavlovian conditioning were presented with either the tone that previously was paired with food delivery (n = 6) or the training context in the absence of tone presentations (n = 5). Approach during the tone (black bars) or the pre-tone (white bars) interval was recorded. Rats presented with the tone exhibited a significant conditioned approach response, making more head insertions during the tone than during the pre-tone interval. Panel B: CREB phosphorylation was determined for NAc samples from rats that were exposed to either the tone or the training context. CREB phosphorylation was significantly higher in NAc samples taken from Pavlovian conditioned rats that were presented with the tone (black bars; n = 6) than in NAc samples from control rats (white bars; n = 5) or from trained rats that were presented with the context only (gray bars; n = 5). No effect of tone presentation was observed on CREB phosphorylation in samples harvested from the dorsal striatum. Representative immunoblots are shown for both pCREB and tCREB from NAc samples taken from Pavlovian trained rats after exposure to either the tone (tone) or the training context in the absence of the tone (cxt) or from control rats (con). * = significantly different at p 0.05. Error bars equal ± 1 SEM.

We compared CREB phosphorylation in NAc samples taken immediately after exposure to the tone or the context only to a control group that was presented with unrewarded tones during both the training phase and the test. We found significantly greater CREB phosphorylation in the NAc of trained rats presented with the tone compared to CREB phosphorylation in control rats or trained rats exposed to the context only (one-way ANOVA: effect of group, F1, 13 = 5.54, p < 0.05; independent samples t-test: tone versus control, t9 = 2.71; tone versus context, t9 = 2.37, both p’s < 0.05) (Figure 2 B). CREB phosphorylation in the dorsal striatum did not differ between groups (p > 0.1) (Figure 2 B). Therefore, the increase in CREB phosphorylation in the NAc after repeated Pavlovian conditioning depends on the presence of the food-associated stimulus, as opposed to the presence of the food or the context in which the tone-food pairings were experienced. It is unlikely that the animals’ approach behavior itself caused an increase in CREB phosphorylation because the correlation between number of head insertions during the test and level of CREB phosphorylation detected after the test across the three groups was not statistically significant (r2 = 0.06, p > 0.1). It could be argued that non-associative processes (e.g., sensitization) contributed to the observed behavioral and biochemical effects. We do not believe that to be the case, however, because CREB phosphorylation was not increased in the context group, which received the same tone-food exposures during training as trained animals exposed to the tone during the test, and because we previously showed that under identical training procedures tone presentations can enhance instrumental responding (Pavlovian-instrumental transfer), a finding that supports our interpretation that the observed effects resulted from a Pavlovian conditioning process (Shiflett et al., 2008).

To further localize the CS-evoked changes in CREB phosphorylation within the NAc, we performed pCREB immunohistochemistry on brain sections taken from rats that were exposed to the tone following 6 days of tone-food pairings. During the test session, discriminated approach was significantly greater in trained rats compared to controls or compared to their own approach behavior during the first training session (independent samples t-test, trained versus control t10 = 4.25, p < 0.01; paired t-test, session 1 versus test, t5 = 2.43, p < 0.05) (Figure 3 A). Immediately after the test, brains were prepared for immunohistochemistry following methods described previously (Thiels et al., 2002). Briefly, rats were anesthetized and rapidly perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde. Forty-μm brain sections were washed and incubated with an antibody that selectively recognizes S133-phosphorylated CREB (1:400; Upstate/Millipore), followed by incubation in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit and then in ABC complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunostaining was visualized with a substrate solution containing DAB. The number of immunopositive cells in the NAc core and shell was estimated from digital images using the NIH ImageJ particle density measurement tool.

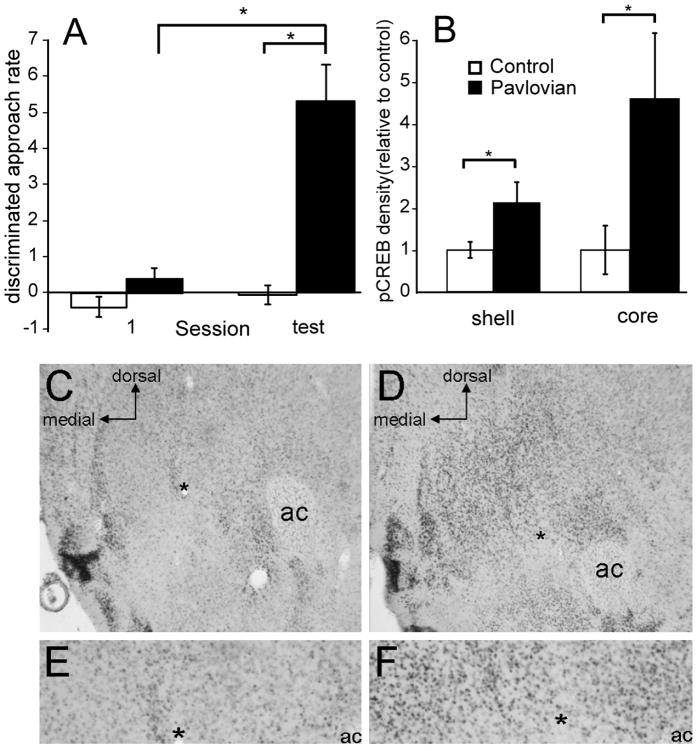

Figure 3.

CS presentation increases pCREB staining in the core and the shell of the NAc. Panel A: Rats that underwent 6 Pavlovian training sessions were presented with the tone in the absence of reward in a single test session. Pavlovian conditioned rats (black bars; n = 6) displayed greater discriminated food-cup approach during the test session compared to control rats (white bars; n = 6) as well as compared to their own performance during the first training session. Panel B: pCREB staining was assessed for both the core and the shell subregion of the NAc from Pavlovian conditioned rats and control rats. A significantly higher density of pCREB positive cells was observed in the NAc core and shell subregions of Pavlovian conditioned rats compared to control rats. Data are presented as percent of control. C–F: Photomicrographs of the NAc core (region surrounding the anterior commissure, ac) and shell (region medial to the core) from a control rat (C and E) and a Pavlovian conditioned rat (D and F). For purposes of reference, the asterisk shown in C and D is re-depicted in E and F, respectively. * = significantly different at p < 0.05. Error bars equal ± 1 SEM.

We found that the density of pCREB immunopositive cells was significantly greater in both the core and the shell of the NAc of trained rats compared to that measured in control animals (independent samples t-tests: NAc core, t10 = 2.25, p < 0.05; shell, t10 = 2.42, p < 0.05) (Figure 3 B–F). These results confirm our observations with Western blot analysis that CS’s an animal has associated with an appetitive outcome increase CREB phosphorylation in the NAc. The results furthermore demonstrate that the increase in CREB phosphorylation occurs in both major sub-regions of the NAc.

Our results show that an increase in CREB phosphorylation in the NAc occurs in response to stimuli associated with natural rewards. These results complement previous research showing that CS presentation increases neural activity and dopamine efflux in the NAc (Roitman et al., 2005; Day et al., 2007). We previously showed that ERK/MAPK signaling is activated in the NAc during presentation of a food-associated CS (Shiflett et al., 2008). It is possible that changes in ERK activation caused by CS presentation give rise to the increase in CREB phosphorylation in the NAc, as was observed in other settings (Haberny and Carr, 2005; Mattson et al., 2005; Li et al., 2008).

It is not known how changes in CREB phosphorylation caused by CS presentation influence behavioral responses to emotionally salient stimuli or to cues that predict such stimuli. Exposure to emotionally salient stimuli transiently increases CREB phosphorylation in the NAc, yet overexpression of CREB in the NAc shell was found to reduce behavioral responses to such stimuli whereas attenuation of CREB to heighten responsiveness (Pliakas et al., 2001; Barrot et al., 2002; Green et al., 2006). One possibility is that prolonged enhancement of CREB function disrupts the process through which transient increases in CREB phosphorylation, such as those evoked by CS presentation, influence behavioral output, whereas prolonged depression of CREB function facilitates this process.

In summary, our results suggest that the processing of cues that predict primary rewarding stimuli involves similar intracellular signaling pathways in the NAc as does the processing of the primary rewards themselves. These signaling pathways, in turn, may modulate behavioral responsiveness to the conditioned cues. Within this framework, the etiology of behavioral disorders, such as addiction, can be understood as perturbations of intracellular signaling in accumbens cells that give rise to abnormal behavioral responses to reward-associated cues and contexts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01046423 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke to E.T. and F32019431 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to M.W.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barrot M, Olivier JDA, Perrotti LI, DiLeone RJ, Berton O, Eisch AJ, Impey S, Storm DR, Neve RL, Yin JC, Zachariou V, Nestler EJ. CREB activity in the nucleus accumbens shell controls gating of behavioral responses to emotional stimuli. PNAS. 2002;99:11435–11440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172091899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Hall J, Everitt BJ. Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:321–352. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Thome J, Olson VG, Lane-Ladd SB, Brodkin ES, Hiroi N, Duman RS, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Regulation of Cocaine Reward by CREB. Science. 1998;282:2272–2275. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JJ, Roitman MF, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Associative learning mediates dynamic shifts in dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1020–1028. doi: 10.1038/nn1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TA, Alibhai IN, Hommel JD, DiLeone RJ, Kumar A, Theobald DE, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Induction of Inducible cAMP Early Repressor Expression in Nucleus Accumbens by Stress or Amphetamine Increases Behavioral Responses to Emotional Stimuli. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8235–8242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0880-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberny SL, Carr KD. Food restriction increases NMDA receptor-mediated calcium--calmodulin kinase II and NMDA receptor/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-mediated cyclic amp response element-binding protein phosphorylation in nucleus accumbens upon D-1 dopamine receptor stimulation in rats. Neuroscience. 2005;132:1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Baldo BA, Pratt WE, Will MJ. Corticostriatal-hypothalamic circuitry and food motivation: integration of energy, action and reward. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:773–795. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo Y-M, Liang KC, Chen H-H, Cherng CG, Lee H-T, Lin Y, Huang AM, Liao R-M, Yu L. Cocaine-but not methamphetamine-associated memory requires de novo protein synthesis. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2007;87:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-Q, Li F-Q, Wang X-Y, Wu P, Zhao M, Xu C-M, Shaham Y, Lu L. Central Amygdala Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Signaling Pathway Is Critical to Incubation of Opiate Craving. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13248–13257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3027-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson BJ, Bossert JM, Simmons DE, Nozaki N, Nagarkar D, Kreuter JD, Hope BT. Cocaine-induced CREB phosphorylation in nucleus accumbens of cocaine-sensitized rats is enabled by enhanced activation of extracellular signal-related kinase, but not protein kinase A. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;95:1481–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Marshall JF. Molecular substrates for retrieval and reconsolidation of cocaine-associated contextual memory. Neuron. 2005;47:873–884. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliakas AM, Carlson RR, Neve RL, Konradi C, Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr Altered Responsiveness to Cocaine and Increased Immobility in the Forced Swim Test Associated with Elevated cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein Expression in Nucleus Accumbens. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7397–7403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07397.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Carelli RM. Nucleus accumbens neurons are innately tuned for rewarding and aversive taste stimuli, encode their predictors, and are linked to motor output. Neuron. 2005;45:587–597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiflett MW, Martini RP, Mauna JC, Foster RL, Peet E, Thiels E. Cue-elicited reward-seeking requires extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1434–1443. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2383-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiels E, Kanterewicz BI, Norman ED, Trzaskos JM, Klann E. Long-term depression in the adult hippocampus in vivo involves activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphorylation of Elk-1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2054–2062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02054.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropea TF, Kosofsky BE, Rajadhyaksha AM. Enhanced CREB and DARPP-32 phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens and CREB, ERK, and GluR1 phosphorylation in the dorsal hippocampus is associated with cocaine-conditioned place preference behavior. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1780–1790. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters CL, Blendy JA. Different requirements for cAMP response element binding protein in positive and negative reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:9438–9444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09438.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters CL, Cleck JN, Kuo YC, Blendy JA. Mu-opioid receptor and CREB activation are required for nicotine reward. Neuron. 2005;46:933–943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]