Abstract

Objectives

To determine the effect of long term inhaled corticosteroids on lung function, exacerbations, and health status in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Design

Double blind, placebo controlled study.

Setting

Eighteen UK hospitals.

Participants

751 men and women aged between 40 and 75 years with mean forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) 50% of predicted normal.

Interventions

Inhaled fluticasone propionate 500 μg twice daily from a metered dose inhaler or identical placebo.

Main outcome measures

Efficacy measures: rate of decline in FEV1 after the bronchodilator and in health status, frequency of exacerbations, respiratory withdrawals. Safety measures: morning serum cortisol concentration, incidence of adverse events.

Results

There was no significant difference in the annual rate of decline in FEV1 (P=0.16). Mean FEV1 after bronchodilator remained significantly higher throughout the study with fluticasone propionate compared with placebo (P<0.001). Median exacerbation rate was reduced by 25% from 1.32 a year on placebo to 0.99 a year on with fluticasone propionate (P=0.026). Health status deteriorated by 3.2 units a year on placebo and 2.0 units a year on fluticasone propionate (P=0.0043). Withdrawals because of respiratory disease not related to malignancy were higher in the placebo group (25% v 19%, P=0.034).

Conclusions

Fluticasone propionate 500 μg twice daily did not affect the rate of decline in FEV1 but did produce a small increase in FEV1. Patients on fluticasone propionate had fewer exacerbations and a slower decline in health status. These improvements in clinical outcomes support the use of this treatment in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide,1,2 and its prevalence is rising.3 It occurs predominantly in tobacco smokers and is characterised by an increase in the annual rate of decline of forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1).4 As lung function deteriorates, substantial changes in general health occur.5 Smoking cessation reduces the rate of decline in FEV1 in people with this disease,6 but no pharmacological intervention has been shown to modify the progression of disease or the associated decline in health status.

In at least 10% of patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease FEV1 will increase significantly after oral prednisolone.7 A large, retrospective, open study reported a reduction in the rate of decline of FEV1 in those taking oral corticosteroids.8 Recently, two studies over three years of inhaled budesonide 800 μg in mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease found no effect of treatment on the rate of decline in FEV1.9,10 Clinical outcomes such as exacerbations, however, were infrequent and health status either showed no benefit of budesonide9 or was not assessed.10

The inhaled steroids in obstructive lung disease in Europe (ISOLDE) study was designed to test the effect of inhaled fluticasone propionate 500 μg twice daily on the rate of decline of FEV1 and other relevant clinical outcomes.

Participants and methods

Participants

Eighteen UK hospitals participated. Patients were current or former smokers aged 40-75 years with non-asthmatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Baseline FEV1 after bronchodilator was at least 0.8 litres but less than 85% of predicted normal, and the ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity was less than 70%. Previous use of inhaled and oral corticosteroids was permitted. Patients were excluded if their FEV1 response to 400 μg salbutamol exceeded 10% of predicted normal, they had a life expectancy of less than five years from concurrent diseases, or they used β blockers. Nasal and ophthalmic corticosteroids, theophyllines, and all other bronchodilators were allowed during the study.

The protocol was approved by each centre's local ethical committee and patients provided written informed consent.

Trial design

Patients were recruited between 1 October 1992 and 31 March 1995. Eligible patients entered an eight week run-in period after withdrawal from any oral or inhaled corticosteroids. After clinic visits at 0, 4, and 8 weeks (visits 0, 1, and 2, respectively) patients were randomised to receive either fluticasone propionate 500 μg or an identical placebo twice daily administered from a metered dose inhaler and with a spacer device by using 10 tidal breaths after each of two actuations. We used a computer generated allocation schedule stratified by centre (block size of six). Patients were randomised sequentially from a list comprising treatment numbers only. Throughout the trial patients used salbutamol (100 μg/puff) or ipratropium bromide (40 μg/puff), or both, for symptomatic relief.

Before the double blind phase, and if not contraindicated, patients received oral prednisolone 0.6 mg/kg/day for 14 days, after which spirometry was performed. These data were used to test whether the acute corticosteroid response could predict those patients who would benefit from long term inhaled corticosteroids. During the three year double blind phase, participants visited a clinic every three months for spirometry, recording of exacerbations, and safety assessments.

The primary end point was the decline (ml/year) in FEV1 after bronchodilator. About 450 patients with two or more measurements of FEV1 during treatment were required to detect a treatment difference of 20 ml/year, assuming a linear decline and a SD of 75 ml/year, with 80% power. Other key end points were frequency of exacerbation, changes in health status, withdrawals because of respiratory disease, morning serum cortisol concentrations, and adverse events.

Measurements

Spirometry measurements were recorded by well trained staff using a standardised procedure on new Sensormedics 2130D spirometers. Quality control included a computer generated check against the ATS criteria11 and a central manual check for acceptability and reproducibility for all measurements, resulting in standards comparable with the lung health study.12 Visits were rescheduled to four weeks after any respiratory infections or exacerbations of the disease.

An exacerbation was defined as worsening of respiratory symptoms that required treatment with oral corticosteroids or antibiotics, or both, as judged by the general practitioner; specific symptom criteria were not used. Patients were withdrawn from the study if the number of exacerbations that required corticosteroids exceeded two in any three month period.

Health status was assessed at baseline and six monthly thereafter by using the disease specific St George's respiratory questionnaire (SGRQ).13 This questionnaire is sensitive to changes in treatment.14 A change in total score of four or more units represents a clinically important change in the patient's condition.5 Serum cortisol concentrations were measured before randomisation (baseline) and every six months during treatment. Samples were taken between 8 am and 10 am and were analysed with the ELISA-Boehringer Mannheim ES700 method.

At each visit patients were questioned about smoking status. Non-smoking was checked with exhaled carbon monoxide and urinary cotinine measurements. Self declared non-smokers were classified as smokers if cotinine was >40 ng/ml or carbon monoxide was >10 ppm at two visits. For analysis patients were categorised as continuous smokers, continuous former smokers, or intermittent smokers during the study.

Statistical analysis

Analyses for each parameter included all randomised patients with at least one valid measurement. To use all patient data we adopted the mixed models approach15 for the primary analysis of FEV1 and total score. This is the most suitable technique for estimating rates of change, with allowance for the correlation structure of repeated measures data. Regression estimates were adjusted for patient differences in the number of observations contributing to the model and for variances within patients.16 Fixed effects were time and five covariates: baseline value centre, age, sex, and smoking status. Baseline FEV1 was the mean at four and eight weeks of the run-in period—that is, at least four weeks after withdrawal of corticosteroids. Subject effects were assumed to be random. The treatment by time interaction tested for a differential treatment effect on the rate of change in FEV1 or respiratory questionnaire score. The model for FEV1 also included a treatment main effect to help to account for the early non-linear treatment changes. Measurements at the end of the prednisolone trial were excluded from the model of decline in FEV1. FEV1 was also compared by using analysis of covariance after 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months to investigate treatment differences over time.

Patient exacerbation rates were calculated as the exacerbation number per treatment days and extrapolated-interpolated to a number per treatment year. The Wilcoxon rank sum test,17 stratified by centre,tested for treatment differences.

Fisher's exact test compared treatment withdrawals due to respiratory causes. These included any non-malignant lower respiratory diseases. Analysis of covariance compared data on log transformed serum cortisol concentration during treatment, adjusted for baseline. Tests were two sided, with a 5% significance level.

Results

Patient demographics

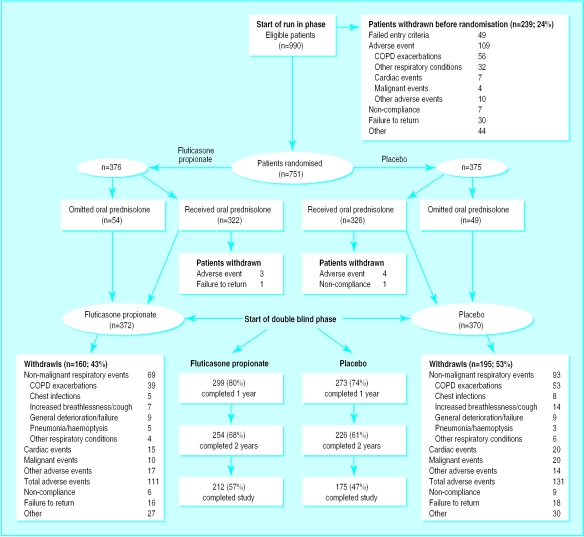

Of the 751 patients randomised, 376 received fluticasone propionate and 375 placebo (figure 1). During the double blind phase, 160 patients (43%) withdrew from the fluticasone propionate group and 195 patients (53%) from the placebo group, the commonest reason being frequent exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mean FEV1 at visit two was 160 ml lower in patients who withdrew from placebo compared with those who did not withdraw (1.30 litre v 1.46 litre); patients who withdrew from fluticasone propionate had a 40 ml higher FEV1 compared with those who did not withdraw (1.44 litre v 1.40 litre). Treatment groups were well matched at baseline (table 1).

Figure 1.

Profile of number of patients at each phase of study

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of randomised population. Figures are means (SD) unless stated otherwise

| Placebo | Fluticasone propionate | |

|---|---|---|

| No of patients randomised | 375 | 376 |

| Age (years) | 63.8 (7.1) | 63.7 (7.1) |

| Women | 97 | 94 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.9 (4.7) | 24.5 (4.8) |

| Evidence of atopy* | 91 | 103 |

| Smoked throughout trial | 147 | 137 |

| Former smoker throughout trial | 172 | 176 |

| Smoking pack years at randomisation† | 44 (34) | 44 (30) |

| Previous use of regular inhaled corticosteroids | 214 | 192 |

| Lung function at visit 0‡: | ||

| After salbutamol (400 μg) FEV1 | 1.40 (0.48) | 1.42 (0.47) |

| As % predicted normal | 50.0% (14.9%) | 50.3% (14.9% ) |

| Change in FEV1 after salbutamol (400 μg) | 0.13 (0.10) | 0.13 (0.10) |

| As % predicted normal | 4.4% (3.4%) | 4.4% (3.5%) |

| After salbutamol (400 μg) FVC | 3.29 (0.80) | 3.37 (0.82) |

| After salbutamol (400 μg) FEV1:FVC | 43.0% (11.0%) | 43.0% (12.0%) |

| Baseline (average of visit 1 and 2)§: | ||

| FEV1 before bronchodilator | 1.23 (0.47) | 1.25 (0.44) |

| FEV1 after bronchodilator (salbutamol 400 μg and ipratropium bromide 80 μg) | 1.40 (0.49) | 1.42 (0.47) |

| Respiratory questionnaire total score¶ | 49.9 (17.4) | 47.7 (17.6) |

FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second in litres; FVC=forced vital capacity.

Atopy was defined as being positive response to skin prick testing with common inhalant allergens. Missing data—placebo: 14; fluticasone propionate: 20.

Missing data—placebo: 37; fluticasone propionate: 16.

Missing data—placebo: 4; fluticasone propionate: 3.

Missing data—placebo: 1; fluticasone propionate: 0.

Score of zero indicates no health impairment and 100 represents worst possible score. Missing data—placebo: 8; fluticasone propionate: 7.

Changes in FEV1

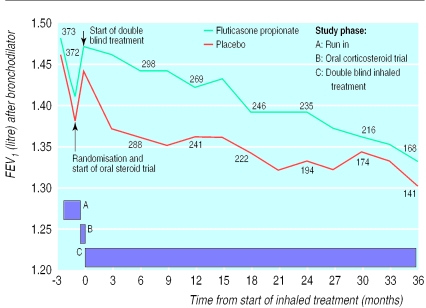

There was a fall in mean FEV1 after bronchodilator during the the run-in (placebo 75 ml, fluticasone propionate 65 ml) (fig 2). The effect was greater in patients who withdrew from inhaled corticosteroids at run-in (89 ml compared with 47 ml in the steroid naive group). After oral prednisolone there was a 60 ml (SD 170 ml) improvement in mean FEV1 after bronchodilator in both treatment groups. Subsequently mean FEV1 declined gradually in the fluticasone propionate group whereas in the placebo group it fell within three months to values before prednisolone treatment.

Figure 2.

Mean FEV1 (litres) after bronchodilator by time from start of double blind treatment. Numbers reflect patients with valid readings at each time point. Measurements within four weeks of exacerbation are excluded. Direct comparisons of FEV1 means at each time point are not possible because fewer patients remained in the study as it progressed

The annual rate of decline in FEV1 was 59 ml/year in the placebo group and 50 ml/year in the fluticasone propionate group (P=0.16) (table 2). This small difference in slopes was uninfluenced by smoking status, age, sex, or FEV1 response to the oral corticosteroid trial. The predicted mean FEV1 at three and 36 months in the fluticasone propionate group was 76 ml and 100 ml higher, respectively, than in the placebo group (mixed effects model P<0.001). The analysis of covariance showed that FEV1 in the fluticasone propionate group was higher than in the placebo group by at least 70 ml at each time point (P⩽0.001). There was no significant relation between FEV1 response to oral corticosteroid or fluticasone propionate (P=0.056).

Table 2.

Results from efficacy analyses. Mixed effects model analyses adjusted for covariates and Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test adjusted for centre

| Efficacy parameter | Placebo | Fluticasone propionate | Treatment difference between drug and placebo (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 after bronchodilator: | ||||

| No of patients | 325* | 339* | ||

| Mean change in FEV1 ml/year (SE) | −59 (4.4) | −50 (4.1) | 9 (6.0) (−3 to 20) | 0.161 |

| Predicted FEV1 at 3 months | 1.37 | 1.44 | 0.076 (0.056 to 0.097) | <0.001 |

| Predicted FEV1 at 3 years | 1.20 | 1.30 | 0.100 (0.064 to 0.135) | <0.001 |

| Health status: | ||||

| No of patients | 291* | 309* | ||

| Mean change in questionnaire score (SE) (units/year) | 3.17 (0.31) | 2.00 (0.29) | −1.17 (0.40) (−1.95 to −0.39) | 0.004 |

| Annual exacerbation rate: | ||||

| No of patients | 370 | 372 | ||

| Mean (SD) rates | 1.90 (2.63) | 1.43 (1.93) | ||

| Median (range) rates | 1.32 (0 to 30) | 0.99 (0 to 26) | −0.3 (−0.4 to 0.0)† | 0.026 |

FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second in litres.

Numbers are smaller than randomised population for FEV1 and health status because of patient withdrawals, missing assessments, or respiratory infections or exacerbations (affects FEV1 only).

Zero values are possible in 95% confidence intervals with non-parametric analyses that show P values ⩽0.05 because method of calculation of confidence intervals differs from non-parametric test.

Exacerbations

The median yearly exacerbation rate was lower in the fluticasone propionate group (0.99 per year) compared with the placebo group (1.32 per year), a reduction of 25% in those receiving fluticasone propionate (P=0.026).

Health status

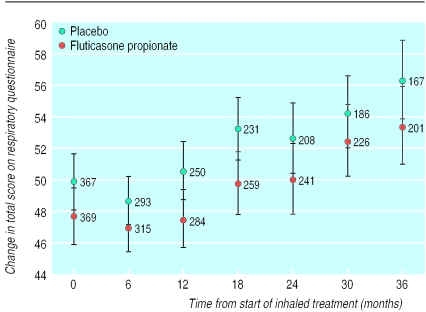

At baseline the total respiratory questionnaire score was not significantly different between treatment groups (table 1), and it did not change significantly over the first six months of treatment (placebo: up 1.2 (SD 11.9); fluticasone propionate: down 0.5 (SD11.8); P=0.09). Thereafter it increased (that is, health status declined) over time (figs 3 and 4). This increase was linear (P<0.0001). The respiratory questionnaire score worsened at a faster rate (P=0.004) with placebo (3.2 units/year) than with fluticasone propionate (2.0 units/year).

Figure 3.

Effect of treatment on decline in health indicated by increasing total scores on respiratory questionnaire (means (95% confidence intervals) calculated from analyses of covariance). Numbers at each assessment indicate number of patients for whom measurements of health status were available at that visit. Direct comparisons of respiratory questionnaire scores at each time point are not possible because fewer patients remained in the study as it progressed

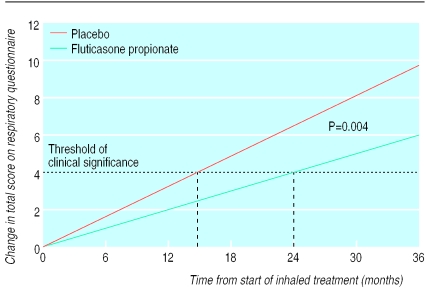

Figure 4.

Weighted regressions from random coefficients (mixed) model (see text) to account for the effect of differences in the number of observations between patients, with adjustment for baseline covariates (baseline questionnaire score, age at entry, sex, centre, and smoking during the study)

Withdrawals

More patients in the placebo group than in the fluticasone propionate group withdrew because of respiratory disease that was not associated with malignancy (25% v 19%, respectively; P=0.034).

Safety

Reported events were similar between treatments (table 3), except for a slightly higher incidence of events related to inhaled glucocorticoid in the fluticasone propionate group.

Table 3.

Number of patients with each category of adverse events during double blind period

| Placebo (n=370) | Fluticasone propionate (n=372) | |

|---|---|---|

| Serious adverse events: | ||

| Any event | 148 | 141 |

| Lower respiratory | 101 | 87 |

| Cardiovascular | 44 | 40 |

| Gastrointestinal | 13 | 19 |

| Deaths: | ||

| Total | 36 | 32 |

| Non-malignant respiratory | 6 | 9 |

| Cardiovascular | 12 | 10 |

| Cancers | 14 | 8 |

| Other | 4 | 5 |

| Inhaled glucocorticoid-related events: | ||

| Hoarseness/dysphonia | 16 | 35 |

| Throat irritation | 27 | 43 |

| Candidiasis of mouth/throat | 24 | 41 |

| Events possibly attributed to systemic absorption: | ||

| Bruising* | 15 | 27 |

| Fractures | 17 | 9 |

| Cataracts | 7 | 5 |

Includes ecchymotic rash (1 placebo patient, 8 fluticasone propionate patients).

There was a significant (P⩽0.032) yet small decrease in mean cortisol concentrations with fluticasone propionate compared with placebo (table 4). No more than 5% of patients on fluticasone propionate had values below the normal range during the study at any time. No decreases were associated with any signs or symptoms of hypoadrenalism or other clinical effects.

Table 4.

Morning serum cortisol concentration (nmol/l) for patients who provided valid data (8 am to 10 am samples only) during double blind period

| Time point | Placebo (n=370)

|

Fluticasone propionate (n=372)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with valid samples | Geometric mean* serum cortisol (CV†) | No (%) of patients with values below normal range (150-700 nmol/l) | Patients with valid samples | Geometric mean serum cortisol * (CV†) | No (%) of patients with values below normal range (150-700 nmol/l) | ||

| Baseline | 265 | 344 (33) | 5 (2) | 265 | 353 (31) | 4 (2) | |

| 6 months | 260 | 345 (33) | 3 (1) | 272 | 311 (42) | 2 (1) | |

| 12 months | 209 | 352 (34) | 3 (1) | 238 | 316 (45) | 13 (5) | |

| 24 months | 136 | 345 (34) | 1 (1) | 160 | 303 (44) | 5 (3) | |

| 36 months | 93 | 354 (33) | 1 (1) | 96 | 310 (35) | 4 (4) | |

| >1 point during double blind treatment | 299 | — | 4 (1) | 331 | — | 17 (5) | |

Least squares means from analysis of covariance of log transformed serum cortisol concentrations were back transformed to give geometric means.

CV=coefficient of variation (%).

Discussion

Inhaled corticosteroids have been used widely in the United Kingdom for the empirical treatment of symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but evidence to support this practice is limited. Unlike early reports,18,19 our study in moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease found no effect of corticosteroids on the rate of decline in FEV1—a finding consistent with two recent budesonide studies in mild disease.9,10 Like Euroscop, a study in continued smokers,10 we found a small improvement in FEV1 after bronchodilator at three months, which was maintained throughout the study. The clinical significance of this change in airway function is unclear. Our study also showed no significant relation between corticosteroid trial response and response to long term inhaled corticosteroid.

The exacerbation rate for placebo was similar to that seen in previous reports,20 but for fluticasone propionate it was 25% lower. Precise definition of an exacerbation is difficult in ambulant patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but, by using the operational approach adopted in ISOLDE, reductions in exacerbation severity were seen in another study of patients with moderately severe disease treated for six months with fluticasone propionate.21 During the ISOLDE run-in we also observed that withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids was associated with an increased likelihood of an exacerbation.22 These observations suggest that inhaled corticosteroids do modify the risk of symptomatic deterioration in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Assessment of of health status is recognised as an important additional measurement in patients with chronic respiratory disease and is a better predictor of admission to hospital and death within 12 months than FEV1.23 The baseline respiratory questionnaire score showed significant impairment, in keeping with other populations with similar reductions in FEV1.13,14 This study shows for the first time that, like FEV1, health status declines at a measurable rate in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Fluticasone propionate significantly reduced this rate of decline, delaying the average time for a clinically important reduction in health status from 15 to 24 months. As the respiratory questionnaire has only a weak correlation with FEV1,5 it must be reflecting other disease components other than airflow limitation.

What is already known on this topic

Inhaled corticosteroids are widely prescribed for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, although there are few studies to support this

A meta-analysis of three small studies showed improvements in FEV1 with high dose beclomethasone dipropionate or budesonide but no benefit from medium dose treatment

In two recent large studies, budesonide in medium dose produced either no benefit or a small initial improvement in FEV1

What this study adds

This study measured progressive decline in health status of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease rather than just the FEV1

In patients with moderate to severe disease, fluticasone propionate 1 mg daily resulted in fewer exacerbations, a reduced rate of decline in health status, and higher FEV1 values than placebo treatment

Serious side effects were similar to placebo, topical side effects were increased

These data provide a rationale for the use of high dose inhaled corticosteroids in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Limitations

Several factors, including disease severity, comorbidity, and study duration, contributed to the high withdrawal rate. Patients were also actively withdrawn from the study and not subsequently followed up if they experienced frequent exacerbations; this is an acknowledged limitation of the study. The effect of the differential rate of withdrawal from treatment is difficult to quantify, nevertheless it is likely to have led to a conservative estimate of benefit with fluticasone propionate.

Reports of adverse events for each treatment were generally similar, although the incidence of events related to glucocorticoids was slightly higher in the fluticasone propionate group. The incidence of fractures was low (2%) and similar to that reported in Euroscop.10 No more than 5% of patients on fluticasone propionate had cortisol concentrations below the normal range at any time during treatment. Similar reassuring data have been reported from a two year placebo controlled study of fluticasone propionate 500 μg twice daily in adults with mild asthma.24

Conclusions

We found no benefit of fluticasone propionate on the rate of decline in FEV1,although small improvements in FEV1 were seen. Unlike the two studies in patients with milder disease, where other clinical outcomes were less measurable,9,10 we found that fluticasone propionate 500 μg twice daily significantly reduced exacerbations and the rate of decline in health status. These data provide a rationale for the current practice of using use of inhaled corticosteroids at this dose in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Acknowledgments

Dr G F A Benfield, Dr M D L Morgan, Dr J C Pounsford, Dr R M Rudd, and Professor S G Spiro provided input into the design of the study. The scientific committee members comprised: Dr G F A Benfield, Professor P M A Calverley, Dr J Daniels, Dr A Greening, Professor G J Gibson, Professor P W Jones, Dr M D L Morgan, Dr R Prescott, Dr J C Pounsford, Dr R M Rudd, Professor D Shale, Professor S G Spiro, Mrs J Waterhouse, Dr J A Wedzicha, and Dr D Weir. The steering committee members were Mrs G Bale, Dr P S Burge, Professor P W Jones, and Dr G F A Benfield. Quality control of spirometry data was supervised by Jonathon Daniels and Geraldine Bale, who also acted as study nurse coordinator. Contributions in recruiting patients and with data collection were provided by Professor J G Ayres, Mrs G Bale, Dr N Barnes, Mrs C Baveystock, Dr G F A Benfield, Ms K Bentley, Dr Birenacki, Ms G Boar, Dr P Bright, Ms M Campbell, Ms P Carpenter, Ms S Cattell, Dr I I Coutts, Dr L Davies, Ms C Dawe, Ms J Dowselt, Ms K Dwyer, Mrs C Evans, Ms N Fasey, Dr A G Fennerty, Dr D Fishwick, Ms H Francis, Dr T Frank, Mrs D Frost, Professor G J Gibson, Dr J Hadcroft, Dr M G Halpin, Mrs O Harvey, Dr P Howard, Dr N A Jarad, Ms J Jones, Dr K Lewis, Mrs F Marsh, Mrs N Martin, Dr M D L Morgan, Ms L Morgan, Mrs W McDonald, Ms T Melody, Dr R D H Monie, Dr M F Muers, Dr R Niven, Dr C O'Brien, Ms V O'Dwyer, Ms S Parker, Dr M Peake, Dr W H Perks, Professor C A C Pickering, Dr J C Pounsford, Mrs K Pye, Mr G Rees, Ms A Reid, Ms K Roberts, Mrs C Robertson, Dr R M Rudd, Ms S Rudkin, Mr S Scholey, Dr P Scott, Dr T Seemungal, Ms S Shaldon, Dr C D Sheldon, Ms T Small, Professor S G Spiro, Dr J R Stradling, Ms H Talbot, Mrs J Waterhouse, Mrs L Webber, Dr J A Wedzicha, and Ms M J Wild.

Footnotes

Funding: GlaxoWellcome Research and Development.

Competing interests: PSB has received financial support for research and attending meetings and has received fees for speaking and consulting. He also has shares in GlaxoWellcome. PMAC has received grant support and has spoken at several meetings financially supported by GlaxoWellcome. PWJ has received funds for research and members of staff from GlaxoWellcome. SS has received funds for research and members of staff from GlaxoWellcome. JAA and TKM are both employed by GlaxoWellcome. Fluticasone propionate is manufactured by Allen and Hanburys, which is owned by GlaxoWellcome.

References

- 1.Thom TJ. International comparisons in COPD mortality. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:27–34. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3_Pt_2.S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1269–1276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher CM, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. BMJ. 1978;1:1645–1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St George's respiratory questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85(suppl B):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS, et al. for the Lung Health Study Research Group. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline in FEV1 JAMA 19942721497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callahan CM, Dittus RS, Katz BP. Oral corticosteroid therapy for patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:216–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-3-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Postma DS, Peters I, Steenhuis EJ, Sluiter HJ. Moderately severe chronic airflow obstruction. Can corticosteroids slow down obstruction? Eur Respir J. 1998;1:22–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vestbo J, Sorensen T, Lange P, Brix A, Torre P, Viskum K. Long-term effect of inhaled budesonide in mild and moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1819–1823. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)10019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pauwels RA, Lofdahl CG, Laitinen LA, Schouten JP, Postma DS, Pride NB, et al. Long-term treatment with inhaled budesonide in persons with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who continue smoking. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1948–1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906243402503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Thoracic Society. Statement: standardization of spirometry, 1987 update. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:1285–1298. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.5.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enright PL, Johnson LR, Connett JE, Voelker H, Buist AS. Spirometry in the lung health study. 1. Methods and quality control. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:1215–1223. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.6.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St George's respiratory questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1321–1327. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meecham Jones DJ, Paul EA, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Nasal pressure support ventilation plus oxygen compared with oxygen therapy alone in hypercapnic COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:538–544. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein H. Multilevel statistical models. 2nd ed. London: Edward Arnold; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models. London: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Elteren PH. On the combination of independent two-sample tests of Wilcoxon. Bull Int Stat Inst. 1960;37:351–361. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dompeling E, van Schayck CP, van Grunsven PM, van Herwaarden CL, Akkermans R, Molema J, et al. Slowing the deterioration of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease observed during bronchodilator therapy by adding inhaled corticosteroids. A 4-year prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:770–778. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-10-199305150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Grunsven PM, van Schayck CP, Derenne JP, Kerstjens HA, Renkema TE, Postma DS, et al. Long term effects of inhaled corticosteroids in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Thorax. 1999;54:7–14. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, Bestall JC, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1418–1422. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9709032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paggiaro PL, Dahle R, Bakran I, Frith L, Hollingworth K, Efthimiou J. Multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial of inhaled fluticasone propionate in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 1998;351:773–780. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)03471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarad NA, Wedzicha JA, Burge PS, Calverley PMA.for the ISOLDE study group. An observational study of inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Respir Med 199993161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osman LM, Godden DJ, Friend JAR, Legge JS, Douglas JG. Quality of life and hospital re-admission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1997;52:67–71. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li JTC, Ford LB, Chevinsky P, Weisberg SC, Kellerman DJ, Faulkner KG, et al. Fluticasone propionate powder and lack of clinically significant effects on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and bone mineral density over 2 years in adults with mild asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:1062–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]