Abstract

In microvillar photoreceptors, light stimulates the phospholipase C cascade and triggers an elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ that is essential for the regulation of both visual excitation and sensory adaptation. In some organisms, influx through light-activated ion channels contributes to the Ca2+ increase. In contrast, in other species, such as Lima, Ca2+ is initially only released from an intracellular pool, as the light-sensitive conductance is negligibly permeable to calcium ions. As a consequence, coping with sustained stimulation poses a challenge, requiring an alternative pathway for further calcium mobilization. We observed that after bright or prolonged illumination, the receptor potential of Lima photoreceptors is followed by the gradual development of an after-depolarization that decays in 1–4 minutes. Under voltage clamp, a graded, slow inward current (Islow) can be reproducibly elicited by flashes that saturate the photocurrent, and can reach a peak amplitude in excess of 200 pA. Islow obtains after replacing extracellular Na+ with Li+, guanidinium, or N-methyl-d-glucamine, indicating that it does not reflect the activation of an electrogenic Na/Ca exchange mechanism. An increase in membrane conductance accompanies the slow current. Islow is impervious to anion replacements and can be measured with extracellular Ca2+ as the sole permeant species; Ba can substitute for Ca2+ but Mg2+ cannot. A persistent Ca2+ elevation parallels Islow, when no further internal release takes place. Thus, this slow current could contribute to sustained Ca2+ mobilization and the concomitant regulation of the phototransduction machinery. Although reminiscent of the classical store depletion–operated calcium influx described in other cells, Islow appears to diverge in some significant aspects, such as its large size and insensitivity to SKF96365 and lanthanum; therefore, it may reflect an alternative mechanism for prolonged increase of cytosolic calcium in photoreceptors.

INTRODUCTION

Light transduction in microvillar photoreceptors is a canonical instance of phosphoinositide signaling (Devary et al., 1987), and in all species that have been examined to date, the photoresponse is accompanied by a large elevation of intracellular free calcium (Brown and Blinks, 1974; Ranganathan et al., 1994; Hardie, 1996). Calcium ions, long known for their pivotal role in light adaptation (Brown and Lisman, 1975), have also been implicated in the regulation of the visual excitation process (Bolsover and Brown, 1985; Payne et al., 1986; Werner et al., 1992; Shin et al., 1993), boosting the gain and speed of the light response (Payne and Fein, 1986). The detailed mechanisms of light signaling downstream of the hydrolysis of PIP2 are yet to be fully elucidated, and there is evidence supporting both the InsP3/Ca2+ branch of the cascade (Brown and Rubin, 1984; Fein et al., 1984; Payne et al., 1986; Shin et al., 1993), as well as DAG or some metabolite thereof (Gomez and Nasi, 1998; Chyb et al., 1999); nonetheless, the undisputed final effect is the opening of ionic channels in the plasma membrane, giving rise to an inward current. Although in all microvillar photoreceptors the light-dependent conductance is cationic, there are significant species differences in ionic selectivity. In some organisms, like Limulus, the light response is due to an influx of Na ions, with little or no detectable contribution by Ca2+ (Millecchia and Mauro, 1969; Brown and Mote, 1974). In contrast, in others, like Balanus and Drosophila, calcium is a major charge carrier of the photocurrent (Brown et al., 1971; Hardie, 1991). Not surprisingly, there are concomitant differences in the source of the Ca2+ mobilized by light. In Limulus and Apis, the light-induced increase of cytosolic Ca2+ is entirely accounted for by release from internal stores (Brown and Blinks, 1974; Baumann et al., 1991) triggered by stimulation of InsP3 receptors (Brown and Rubin, 1984), which are confined to the light-sensitive lobe of the cell (Payne and Fein, 1986). In Balanus and Drosophila, instead, this is attributable primarily to influx, as removal of extracellular calcium greatly depresses the Ca2+ elevation (Brown and Blinks, 1974; Ranganathan et al., 1994). Because of the ubiquitous role of calcium in the regulation of light responsiveness, intense and/or prolonged photostimulation poses a challenge for those cells possessing light-activated channels that are poorly permeable to this ion, as the internal pool of calcium is inevitably limited. This suggests that an alternate pathway of influx must be available. We addressed this problem by examining microvillar photoreceptors of the marine mollusk Lima scabra because an extensive electrophysiological characterization had lead to the conclusion that there is minimal, if any, permeation of calcium through the light-sensitive channels (Gomez and Nasi, 1996). Through the combined use of patch clamp recording and calcium fluorescence measurements, we identified a slow Ca-dependent inward current that only becomes manifest under a regimen of intense photostimulation when further internal release cannot be sustained. This novel conductance fulfills the requirements for mediating the persistent elevation of intracellular calcium necessary to regulate the light-transducing machinery under such conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens of Lima scabra were obtained from Carolina Biological. Eyecups were dissected under dim red illumination and enzymatically dispersed as described previously (Nasi, 1991a). The resulting suspension of dissociated microvillar photoreceptors was plated in a recording flow chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope. The chamber was continuously superfused (≈1 ml/min) with artificial sea water (ASW); a system of manifolds permitted the exchange of the superfusate. For rapid local solution changes, a puffer micropipette was positioned in the vicinity of the cell and could pressure-eject a stream of test solution upon activation of a solenoid-operated valve. Test compounds that required intracellular administration were dialyzed via the patch pipette.

Whole cell patch clamp recordings were performed as described previously (Nasi, 1991b). Signals were low-pass filtered at 100 Hz for slowly changing currents and at 1,000 Hz for the rapid light-evoked current using a Bessel four-pole filter. Records were digitized online at a sampling rate of 200 Hz and 3 KHz, respectively. Further digital filtering was used on some recordings. All cell manipulations were performed under dim near-infrared illumination (long-pass filter, λ > 715 nm; Andover). Light flashes were generated by a conventional optical stimulator delivering small spots of light (≈200 µm in diameter). Broadband stimulation was used unless otherwise specified. An in vivo calibration was used to quantify light intensity in terms of effective photons × s−1 × cm−2 at 500 nm, as measured with a radiometer (United Detector Technology). Neutral density filters were interposed in the light path to adjust incident light intensity. Voltage and light stimuli were applied by a microprocessor-controlled programmable stimulator (Stim 6; Ionoptix).

Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ were detected using visible light fluorescent indicators (Calcium Green 5N, Fluo 4, and Oregon Green 2; Invitrogen). The potassium salt of the probe was dissolved in the intracellular solution filling the patch electrode at a final concentration of 60–100 µM. Excitation light provided by a 75-W arc lamp (Xenon; PTI) was filtered by a dichroic reflector to reject wavelengths longer than 670 nm (Omega Optical), and by an interference filter (480 nm, 40-nm bandwidth; Chroma Technology Corp.). The beam was brought to the epi-illumination port of the microscope via a liquid light guide (Oriel Corporation). The dichroic reflector in the microscope turret had a cutoff wavelength of 505 nm. Emission light collected by a 100×, 1.3 numerical aperture oil-immersion objective (Nikon) was filtered sequentially by an additional dichroic (λ < 610 nm) and by a 535-nm interference filter (50-nm bandwidth; all from Chroma Technology Corp.). An adjustable mask (Nikon) located at a conjugated image plane was positioned under infrared visualization to restrict the collected light to a rectangular region of interest (the light-sensitive lobe of the cell, unless otherwise stated) and thus minimize background light. The fluorescence signal was detected by a photomultiplier tube (model R4220 PHA; Hamamatsu Photonics) operated at 800 V in photon-counting mode, using a window discriminator and a rate meter (F-100T and PRM-100; Advanced Research Instruments). An analogue voltage proportional to the counts accumulated in bins of programmable duration was fed to the A/D interface of the computer.

Solutions

ASW contained (in mM): 480 NaCl, 10 KCl, 10 CaCl2, 49 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5.5 glucose, pH 7.8 (NaOH). In Na-free sea water, sodium was replaced by NMDG, lithium, or guanidinium. In (nominally) calcium-free ASW, calcium was replaced iso-osmotically with magnesium, without adding chelators. In low-chloride ASW, [Cl] was reduced by 500 mM, replacing NaCl and CaCl2 with Na- and Ca-gluconate, respectively. To test the permeation of different divalent cations, the extracellular solution contained 60 mM calcium, barium, or magnesium, 490 mM NMDG Cl, and 10 mM HEPES/Tris. The standard intracellular solution used to fill whole cell micropipettes contained 200 mM K-glutamate, 100 mM KCl, 22 mM NaCl, 5 mM Mg ATP, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 100 µM GTP, and 300 mM sucrose, pH 7.3. In some instances, intracellular sodium was omitted to forestall the possibility of reverse operation of the Na/Ca exchanger. To increase Ca buffering capacity, EGTA was raised to 10 mM. The internal solution with elevated Ca2+ had a similar composition, except that 0.5 mM CaCl2 was added to it with 1 mM tetrafluoro-BAPTA (instead of EGTA; Invitrogen), yielding an estimated free calcium concentration of ≈50 µM. For perforated patch recording, the solution used to backfill the electrode contained 0.1 mg/ml nystatin, and membrane perforation was monitored by the gradual appearance of capacitative transients elicited by voltage steps. We also used β-escin (Fan and Palade, 1998), which produces more sizable pores but still prevents the washout of molecules >10 kD. SKF96365 hydrochloride was purchased from EMD.

RESULTS

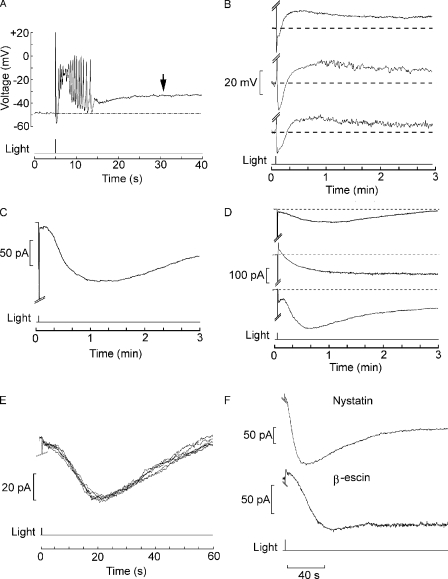

The receptor potential of Lima rhabdomeric photoreceptors has a complex waveform (Nasi, 1991a), owing to the presence of two distinct conductances that are directly dependent on light stimulation (Nasi, 1991c) as well as voltage- and calcium-dependent ion channels that shape its time course (Nasi, 1991b) and endow these cells with the ability to generate propagating action potentials (Mpitsos, 1973). As the intensity of stimulating flashes is raised to high levels, an additional feature appears: seconds after the receptor potential (generally accompanied by one or more action potentials), the membrane voltage gradually depolarizes by 10–20 mV (Fig. 1 A, arrow). The voltage remains depolarized for 1–3 min, and then slowly returns to the dark resting level. Fig. 1 B illustrates the prolonged time course of this phenomenon, recorded in different cells. During the after-depolarization, light responsiveness is greatly depressed. We used voltage clamp recording to investigate this long-lasting electrical response evoked by light. Fig. 1 C demonstrates that a bright flash delivered from a holding voltage near the cell's resting potential elicits a slow inward current (henceforth referred to as Islow), with temporal characteristics that parallel those of the aforementioned after-depolarization (the early, truncated downward transient is the primary photocurrent, highly compressed at this time scale). Islow amplitudes typically vary between 50 and 250 pA (113 ± 37 pA SD in 22 cells tested under the same stimulation conditions). The phenomenon is robust and reproducible (n > 100), although there is across-cells variability not only in the peak amplitude of the slow light-induced inward current, but also in its time course; nonetheless, its duration is consistently at least two orders of magnitude greater than that of the primary photocurrent. The three examples in Fig. 1 D illustrate the range of variability in size and duration. Islow can be triggered repeatedly in a given cell, and its features are reproducible, provided that the stimulation is not too intense (Fig. 1 E); in fact, this slower response often proved to be more robust than the photocurrent itself. To rule out the possibility that Islow may artifactually result from the perturbation of the intracellular milieu or the loss of cell constituents during dialysis by the patch pipette, we resorted to the minimally invasive perforated patch technique (Horn and Marty, 1988). Fig. 1 F shows a current trace recorded after perforation of the membrane patch with nystatin; Islow is indistinguishable from the currents recorded by means of the conventional whole cell patch clamp technique (n = 4). A similar result was obtained with β-escin (n = 2).

Figure 1.

Prolonged aftereffects of intense illumination in Lima rhabdomeric photoreceptors. (A) Current clamp recording in a cell stimulated with a bright flash of light (5.4 × 1015 photons × cm−2 × s−1). After the complex-shaped receptor potential and a train of action potentials, membrane voltage drifted in the depolarizing direction by ≈15 mV. (B) Recordings in three different cells, shown at a more compressed time scale, to illustrate the prolonged time course of the after-depolarization. (C) A similar photostimulation applied to a different cell under whole cell voltage clamp, internally dialyzed with standard intracellular solution. A Islow started to develop several seconds after the photocurrent (which was truncated, as its amplitude of several nA would fall off-scale at this gain). Holding potential of −60 mV. (D) Slow after-current in three different cells to illustrate the variability in amplitude and time course. (E) Repetitive activation of Islow in the same cell, exposed to a flash attenuated by 0.6 log compared with the trace in C and D. (F) Islow obtains in photoreceptors voltage clamped by the perforated patch technique. The two examples show the current evoked by a 100-ms flash (1.4 × 1015 photons × cm−2 × s−1) in photoreceptor cells in which access to the cytoplasmic compartment was attained by adding the pore-forming agent nystatin to the pipette filling solution, or β-escin. In all these examples, the extracellular solution was ASW.

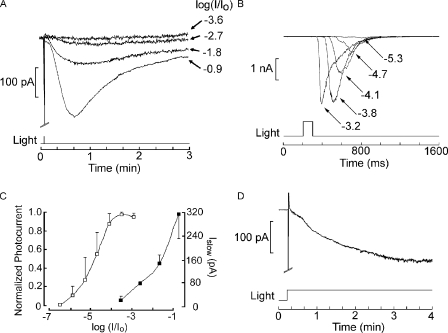

A striking feature of Islow is that with dim or moderate illumination it is virtually undetectable and only becomes conspicuous at light intensities in the saturating range for the photocurrent. From that point on, its amplitude is graded with stimulus intensity, while the size of the photocurrent remains essentially unchanged. Fig. 2 A shows the Islow elicited repetitively by flashes of progressively higher intensity. Fig. 2 B illustrates instead a typical intensity series for the photocurrent recorded in a different cell and displayed at a lower gain and faster time scale. It can be appreciated that Islow only appears with flash attenuation (−2.7 log) at which the photocurrent has already attained its maximal amplitude, and continues to increase monotonically over at least 2 log units (n = 2). In Fig. 2 C, the average intensity–response relation was plotted for both the regular photocurrent and for Islow (n = 3 in each case) to highlight the profound difference in light intensity dependency (≈3 log units). Fig. 2 D shows that the slow current also obtains with prolonged illumination of more moderate intensity, such as it may prevail in shallow waters on a sunny day, indicating that its occurrence is not alien to the conditions that the organism is likely to encounter in its environment, which is sub-tidal to a few meters of depth (where total incident light flux can be in excess of 1016 photons × cm−2 × s−1).

Figure 2.

Light intensity dependence of the Islow. (A) Islows evoked in a cell stimulated with 100-ms flashes of increasing intensity, as indicated by the attenuation factor on the right. (B) Intensity series for the photocurrent in a different photoreceptor displayed at a faster time scale. The amplitude of the response reaches saturation at a stimulus intensity below the threshold for the slow current. (C) Plot of the peak amplitude of the photocurrent (open symbols) and that of the slow aftercurrent (filled symbols) averaged for three cells in each condition. Error bar indicates SEM. (D) The slow current is also elicited with more modest stimulus intensities, provided that their duration is extended. The panel shows the response to a step of light attenuated by −1.8 log but maintained for the duration of the recording. Holding potential of −50 mV in all panels, unattenuated light intensity of 19 × 1015 photons × cm−2 × s−1.

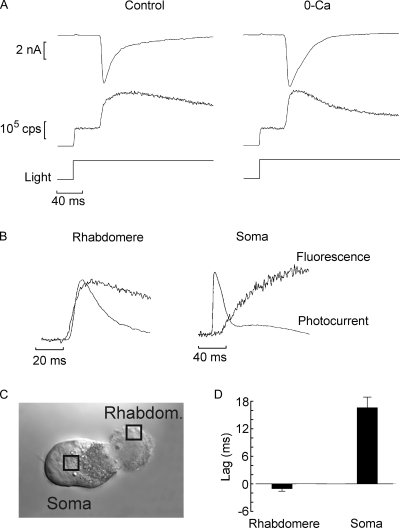

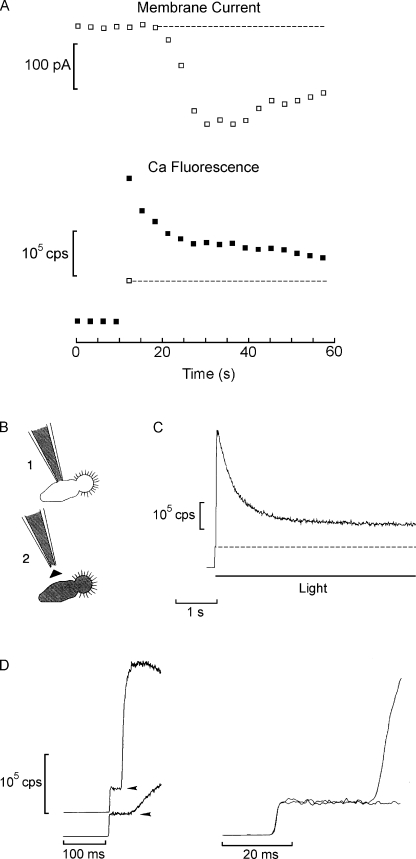

Illumination of Lima microvillar photoreceptors produces a large elevation of cytosolic Ca2+. Fig. 3 A (left) illustrates an example of simultaneous measurement of membrane current and Ca fluorescence in a voltage-clamped cell. A low-affinity indicator, Calcium Green 5N, was loaded by perfusion via the patch pipette at a final concentration of 63 µM. Activation of the epi-illumination beam triggered two events: (1) a vigorous inward photocurrent (Fig. 3 A, top trace), and (2) an instantaneous transition of the photomultiplier output signal (reflecting the basal fluorescence), followed by a large Ca2+ rise concomitant with the onset of the photocurrent (middle trace). The fluorescence reached a peak within ≈70 ms from the beginning of the light and then decayed. Fig. 3 A (right) demonstrates that light-induced Ca2+ transients survive removal of extracellular calcium (the apparently more rapid decay in calcium-free medium was not consistently observed, and likely reflects cell-to-cell variability). This indicates that the underlying mechanism is mobilization from internal stores. Further support for this contention is provided by spatially resolved measurements of the activation kinetics of the calcium signal, relative to that of the electrical response. To this end, the optical recording was circumscribed to a small window, ≈3 × 3 µm, the position of which was manipulated under infrared light visualization. The arrangement is illustrated in Fig. 3 C, which shows a Nomarski micrograph of a photoreceptor with the positions of the optical mask indicated by squares. In Fig. 3 B, membrane current (inverted for display purposes) and Ca fluorescence traces were normalized and overlaid. When the fluorescence signal was recorded from the microvillar lobe (Rhabdomere), the rise in calcium slightly preceded the photocurrent onset. When the window was positioned onto the cell body (Soma), the Ca fluorescence rise significantly lagged behind the membrane current (notice the different time scales). In Fig. 3 D, pooled data for a group of cells are shown in a bar graph. In the microvillar lobe, the calcium signal led the light-evoked current by 1.1 ± 0.95 ms (SD; n = 14), whereas when the fluorescence was recorded from the middle of the somatic lobe, it lagged by an average of 16.4 ± 2.1 ms (n = 5). The amplitude of the Ca fluorescence signal was also different, being significantly larger in the microvillar lobe than in the soma (not depicted). In conclusion, Ca2+ elevation originates in the photosensitive region of the photoreceptor, it precedes the opening of light-dependent ion channels, and it does not require extracellular calcium; as a consequence, it must implicate light-induced intracellular release.

Figure 3.

Light stimulation releases calcium from intracellular stores in the microvillar lobe of Lima photoreceptors. (A) Simultaneous recording of membrane current under voltage clamp (top traces) and fluorescence of the indicator Calcium Green 5N, which was dialyzed through the patch pipette at a concentration of 63 µM (bottom traces). A large increase in fluorescence above the initial level occurred shortly after activating the epi-fluorescence beam, coincident with the beginning of the photocurrent. A similar Ca2+ transient was observed in a cell superfused for 8 min with nominally calcium-free solution (right). (B) The Ca2+ transient originates in the microvillar lobe and precedes the opening of the light-dependent channels. The fluorescence was recorded from a small window positioned either on the microvillar lobe (Rhabdomere) or on the cell body (Soma), as indicated in C. The signal from the rhabdomere slightly preceded the membrane current (inverted for display purposes and normalized), whereas that from the cell body lagged behind the electrical response by many milliseconds. (D) Pooled data of the temporal shift between current and fluorescence, averaged for several cells tested in the two arrangements.

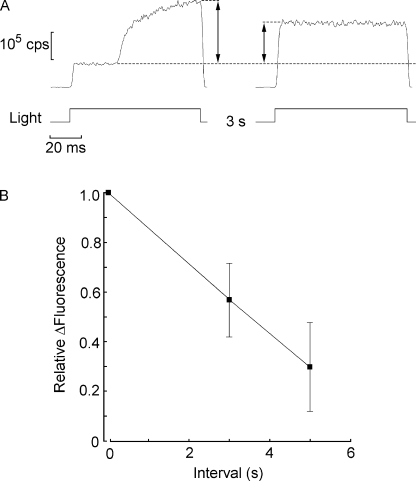

After termination of photostimulation, the large accumulation of cytosolic calcium is rapidly reduced, as determined by a double-stimulus protocol. In such measurements, the excitation light is presented briefly twice (80–100 ms each time, sufficient to encompass the peak of the light-induced Ca2+ increase). The duration of the intervening interval is varied across cells. As shown in Fig. 4 A, the first flash (left) evoked a conspicuous rise in fluorescence over the initial baseline level (marked by a dotted line). In these and all subsequent fluorescence measurements, the optical mask restricted light collection to the whole light–sensitive rhabdomeric lobe. Upon reopening the shutter the second time (Fig. 4 A, right), no additional light-induced calcium increase was observed; however, the level of fluorescence remained significantly elevated, but not as high as the peak attained with the first flash. By comparing the relative fluorescence (ΔF/F) at the peak of the first response with that in the second flash as the interval is varied, one can determine the time course of the fall in Ca fluorescence after the light is turned off. The plot in Fig. 4 B shows that in 3 s the residual calcium signal had decayed to ≈58 ± 15% (n = 6), and in 5 s it decreased to 30 ± 18% (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Rate of decay of the calcium signal. (A) Fluorescence was measured in response to pairs of brief flashes (90 ms) spaced 3 s apart. Light was only collected from the photosensitive microvillar lobe. The first light evoked a large increase in Ca fluorescence above the basal level. At the time the second flash was presented, fluorescence remained significantly elevated, and no further increase was elicited. (B) Average amplitude of the fluorescence signal during the second stimulus, normalized with respect of the initial peak amplitude, as the interval separating the two flashes was increased from 3 to 5 s. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

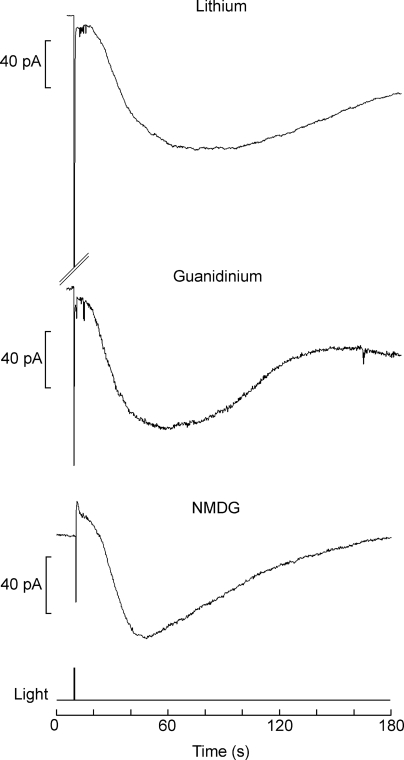

One mechanism that has been implicated in restoring basal Ca2+ levels in microvillar photoreceptors is the Na/Ca exchanger, which, owing to the stoichiometry of the countertransport process (Na/Ca > 3), entails at least one charge being inwardly translocated per cycle. We investigated whether Islow may reflect the activation of an electrogenic Na/Ca exchanger. Considering the sluggish onset of this current (in contrast with the rapid elevation of [Ca2+]i), this possibility would require that the exchanger be spatially segregated with respect to the source of calcium. We tested the effect of removing extracellular sodium to prevent forward operation of the exchanger. Fig. 5 shows recordings in different cells after replacement of extracellular Na. Substitution with Li (n = 9) resulted in a slow current with normal characteristics, indistinguishable from control measurements. Similar results were obtained with guanidinium (n = 3) and NMDG (n = 8); compared with lithium, the only salient difference was the reduction in the amplitude of the initial light response, as expected from the fact that guanidinium and NMDG permeate poorly through the light-sensitive channels, whereas lithium can substitute for Na+ as the carrier of the inward photocurrent (Gomez and Nasi, 1996).

Figure 5.

Islow is not due to a Na/Ca exchanger. To evaluate the possibility that the slow current may reflect the activity of an electrogenic Na/Ca exchanger triggered by the light-evoked increase in cytosolic Ca2+, cells were stimulated with bright flashes while superfused with solution containing no sodium. The slow current was still observed, regardless of the replacement of extracellular sodium. With lithium, which permeates readily through the light-dependent ion channels, a large photocurrent (truncated in the figure) was also elicited. During superfusion with guanidinium or NMDG, in contrast, the initial inward current was severely reduced (<100 pA), as the photoconductance is poorly permeable to these ions; nonetheless, the subsequent slow current developed normally, both in terms of time course and amplitude. Light intensity of 1.6 × 1015 photons × cm−2 × s−1; holding potential of −60 mV.

One can conclude that Islow is not the electrical manifestation of the sodium-dependent extrusion of the calcium released upon photostimulation. Rather, it appears to correlate with a sustained increase in cytosolic calcium for the following reasons: the data in Fig. 4 indicate that after a brief flash of very high intensity, such as the epi-fluorescence excitation beam, subsequent flashes do not release additional Ca2+ (as indicated by the flat time course of the fluorescence trace during the second flash). Because the clearance of the calcium load occurs with an initial time constant of <5 s, one would expect [Ca2+]i to return to baseline levels within 20 s or less. Instead, it remains elevated for tens of seconds. This is illustrated in Fig. 6 A, which shows a measurement of membrane current and Ca fluorescence protracted over a 1-min period. Because we were interested in the lower amplitude plateau elevation of Ca2+, a higher affinity indicator was chosen for this task (Fluo 4). To minimize bleaching of the calcium indicator, the epi-fluorescence illumination was not continuous but pulsed, delivering 80–100-ms flashes every 3 s, and the fluorescence was sampled concomitantly with the membrane currents during such episodes. Four readings were taken before initiating the train of flashes (for the fluorescence channel, these represent “dark” counts). With the first flash, the fluorescence signal displayed a sharp rise (both the “foot” level of basal fluorescence and the peak are plotted in the graph, represented by the open and the filled squares, respectively), and then decayed on subsequent trials, stabilizing at a level that was higher than the initial fluorescence. Concomitantly, several seconds after the first flash, Islow started to develop, reaching an amplitude of 186 pA. On average, the plateau fluorescence at the end of the recording was higher than the basal level by 20 ± 8.5% (SEM; n = 5). Because even with the pulsed protocol the cumulative light exposure was not inconsequential, we gauged whether significant bleaching of the probe may have occurred. To eliminate the confounding due to the continuous replenishment via dialysis, the patch pipette was withdrawn after loading the dye into the photoreceptor, as depicted schematically in Fig. 6 B. The epi-illumination beam was turned on for 5 s, producing the characteristic Ca fluorescence increase (Fig. 6 C). Then, after 5–10 min in the dark, another briefer light was administered. The duration of the rest period was chosen to allow for the Ca2+ elevation to clear and for Islow to die out. As shown in Fig. 6 D, the foot of the optical signal on the second stimulation (shown also on an expanded time scale on the right) was not significantly depressed with respect to the initial basal fluorescence level, suggesting that bleaching of the Ca dye was marginal (n = 3); therefore, the plateau Ca fluorescence in Fig. 6 A was not underestimated. The persistent, though modest, elevation of cytosolic calcium, in spite of the lack of any further detectable photo-induced release after the initial flash, implies that some source of Ca2+ must be active. The fact that the lingering Ca fluorescence paralleled the slow current suggests that the latter may be associated with Ca2+ influx.

Figure 6.

A sustained elevation of calcium accompanies the slow current. (A) Membrane current was measured concomitantly with Ca fluorescence of the rhabdomeric lobe in a cell loaded with the indicator Fluo 4 (83 µM). Recordings were made every 3 s; after four baseline measurements, excitation flashes (90 ms in duration) were delivered repetitively. The top graph shows the development of the slow current. The bottom graph plots the fluorescence signal, which decayed partially after the initial large increase, but remained significantly elevated with respect to the basal level. The open square and dotted line mark the basal fluorescence level during the first flash, and the highest point represents the peak fluorescence level attained during the same flash (in subsequent flashes the trace was flat during the light, as there was no further release; therefore, the “foot” vs. “peak” distinction is not made). (B) To estimate whether dye bleaching might contribute significantly to the decay of the fluorescence signal, owing to the extended light exposure, photoreceptor cells were loaded with the Ca indicator for ≈4 min and the pipette was withdrawn to prevent any further dye exchange. (C) The epi-fluorescence beam was activated for 5 s, evoking a large optical signal that decayed to a plateau (basal fluorescence is indicated by the dotted line). (D) After 10 min, the excitation light was turned on again, and the basal fluorescence was found not to be noticeably depressed with respect to the initial level (i.e., immediately after the first opening of the shutter). The initial portion of both fluorescence traces is displayed (on the left they were displaced vertically for clarity; the arrowheads mark the basal fluorescence levels). The slower rise of the light-induced Ca2+ increase on the second trial indicates physiological rundown. On the right, the same traces are superimposed and shown on an expanded time scale. Because no replenishment of dye was possible under these conditions, the results indicate that a 5-s exposure to the excitation light did not result in significant bleaching of the calcium probe.

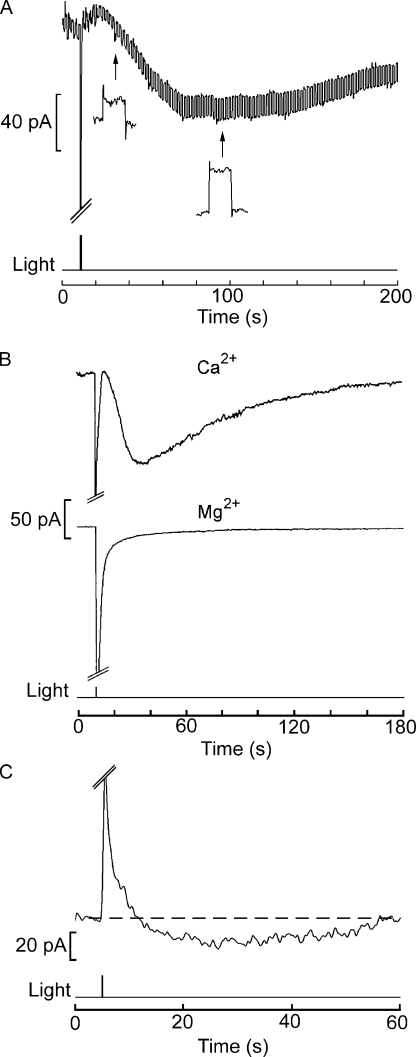

The following clues support such conjecture. In the first place, measurements of input resistance of the cell after delivery of a bright flash reveal that an increase in membrane conductance is responsible for Islow. In Fig. 7 A, a photoreceptor was voltage clamped at −60 mV, but the holding potential was subjected to a repetitive square-wave perturbation (10 mV amplitude, 10 Hz, 50% duty cycle). Stimulation with a bright flash triggered the slow current; concomitantly, the amplitude of the current excursions produced by the voltage steps grew (Fig. 7 A, insets), reporting an increase in membrane conductance. With saturating flashes, the conductance change was approximately sixfold, from 2.8 ± 0.7 nS (SEM) to 13.4 ± 3.7 nS (n = 13), for an average peak amplitude of Islow of 255 ± 39.6 pA. These values would predict an average peak amplitude of the prolonged depolarization on the order of ≈19 mV, consistent with the values measured under current clamp (see Fig. 1 B).

Figure 7.

The slow current results from an increase in a Ca-permeable membrane conductance. (A) The photoreceptor input resistance was continuously monitored by applying a repetitive rectangular command step, 10 mV in amplitude, superimposed upon the steady holding potential (−60 mV). After the flash, the size of the current steps gradually increased (insets) concomitantly with the development of the slow current, indicating a reduction in membrane resistance. (B) To assess the permeation of individual divalent cations, photoreceptors were tested in an extracellular solution containing either 60 mM Ca2+ or 60 mM Mg2+ as the sole divalent species. The internal solution contained no sodium to prevent calcium loading via reverse operation of the Na/Ca exchanger, and the holding potential was set at −50 mV. A robust Islow was observed in the presence of Ca2+ (top trace), whereas it was entirely absent with Mg2+ (bottom trace). Light intensity of 3.2 × 1015 photons × cm−2 × s−1. (C) Islow does not invert with membrane depolarization to +40 mV, whereas the primary photocurrent does. The holding potential was stepped a few seconds before the recording. Although considerably reduced in amplitude, the slow current remained inwardly directed.

Second, the slow current is cationic and carried at least in part by calcium. The participation of chloride was dismissed upon observing that a reduction in extracellular Cl concentration from 608 to 108 mM by equi-molar replacement with gluconate produced no significant effects on the slow current (not depicted; n = 3). Likewise, the data shown in Fig. 5 rule out a unique contribution of Na+. The permeation of calcium was assessed by superfusing the cell with solutions containing only one divalent cation at a time. With 60 mM CaCl2, a robust Islow was observed, as shown by Fig. 7 B (top trace). In contrast, if magnesium was the only divalent cation in the extracellular solution, the slow current was virtually absent (Fig. 7 B, bottom trace; n = 4). Barium could substitute for Ca2+ (not depicted). In these experiments, the internal solution contained no sodium to prevent calcium loading via reverse operation of the Na/Ca exchanger. Fig. 7 C shows that the slow current remains inwardly directed at holding potentials up to +40 mV (n = 3). Larger depolarizations proved deleterious to the cells (even when the recording window was shortened to 1 min, like in Fig. 7 C), so we were unable to revert Islow; moreover, the presence of voltage- and calcium-activated currents of considerable amplitude (several nA) (Nasi, 1991b) would likely defeat any attempt to obtain an accurate estimate of its Vrev.

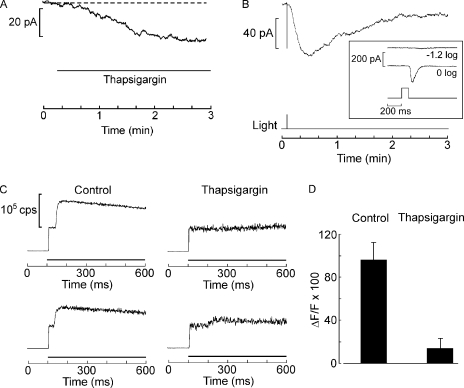

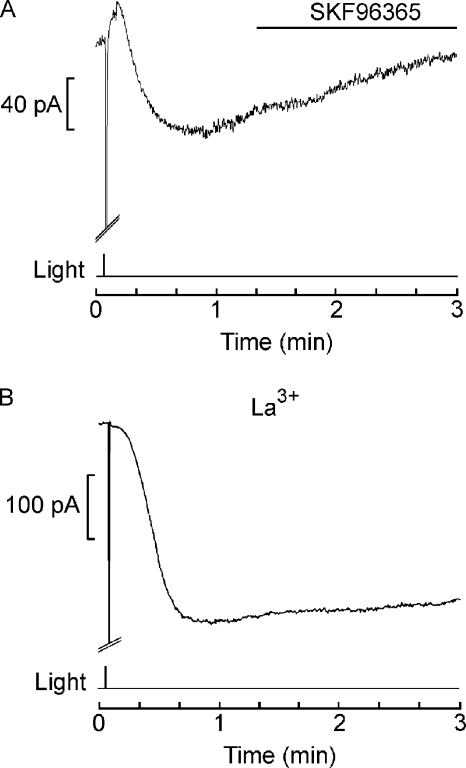

The properties of Islow described above are reminiscent of those of store-operated currents that have been described in a wide variety of cells that use InsP3-mediated Ca signaling. An important experimental tool for determining that they depend on the filling state of the internal calcium stores per se (rather than messengers generated by the PLC pathway) is thapsigargin, an inhibitor of the calcium pump of the endoplasmic reticulum (SERCA). Thapsigargin can slowly empty calcium stores and trigger a sustained subsequent influx of calcium in many cell types. We found thapsigargin (400 nM) to be minimally effective in altering membrane current in voltage-clamped Lima photoreceptors. Fig. 8 A shows the largest effect we observed in response to local application via a puffer pipette. A slowly developing inward current attained an amplitude of ≈30 pA. Another cell produced an even smaller current (<10 pA), and a third did not respond at all. Monitoring the membrane current for several additional minutes beyond the interval shown in Fig. 8 A did not alter this state of affairs. Thapsigargin-treated cells were still able to produce Islow (Fig. 8 B) with an amplitude not significantly different from that of control cells (107 ± 27.2 pA SD; n = 3); however, as shown by the inset of Fig. 8 B, the primary photocurrent was greatly depressed, attaining a size of only a few hundred pA (compared with several nA in control cells; see Fig. 2 B). To further assess whether the thapsigargin treatment was effective, the light-evoked elevation of intracellular calcium was monitored with fluorescent indicators. Fig. 8 C shows the fluorescence in control cells and in cells treated with 400 nM thapsigargin. The drug nearly abolished the large, rapid elevation of Ca2+ that typically begins ∼30 ms after opening the epi-illumination shutter. The data averaged from six cells, three in each condition, are summarized by the bar graph in Fig. 8 D. We then turned to agents reported to block the capacitative calcium influx. Fig. 9 A shows that puffer application of 50 µM SFK96365 during Islow failed to alter its time course (n = 4). Application by continuous bath superfusion was also ineffective (n = 2). Lanthanum has also been reported to block capacitative Ca2+ influx at submillimolar concentrations in several cell types. Fig. 9 B shows that during extracellular application of 1 mM La3+ by continuous superfusion of the entire recording chamber, a very conspicuous Islow could still be elicited; another cell generated a slow current of 148 pA. To assess whether Islow had suffered any attenuation at all, we resorted to a more sensitive within-cell comparison and found that, once the slow current had fully developed, brief local application of lanthanum produced only a marginal inhibitory action (≈15%; n = 4; not depicted). In several key aspects, therefore, Islow departs from the features commonly encountered in store-operated currents.

Figure 8.

Islow is not solely controlled by store depletion. (A) Application of 400 nM thapsigargin in the dark by local superfusion (indicated by the horizontal line beneath the trace) only produced a very small change in membrane current. Holding potential of 50 mV. (B) Islow evoked in a thapsigargin-treated cell has a normal amplitude and time course. (Inset) Photocurrent measured in response to bright flashes, showing that the light response is greatly attenuated. (C) Effect of thapsigargin on light-evoked calcium mobilization. Cells were loaded with 83 µM Oregon Green2 by dialysis. Compared with the pronounced increase in Ca fluorescence consistently recorded in control cells (left traces), in thapsigargin-treated cells (400 nM) the calcium transient is either abolished or dramatically attenuated (right). (D) Average light-induced increase in Ca fluorescence for three control cells and three cells exposed to thapsigargin. Error bars indicate SEM.

Figure 9.

Lack of effects of antagonists of store-operated currents on Islow. (A) 50 µM SKF96365 was continuously pressure-ejected by a puffer pipette, beginning shortly after the slow current had peaked (horizontal line). There was no discernible alteration in the time course of the current, indicating that Islow was not suppressed. Vh = −50 mV; light intensity of 28.6 × 1015 × photons × cm−2 × s−1). (B) A large-amplitude Islow elicited in the presence of 1 mM La3+ (applied by extensive bath superfusion before applying the light stimulus). Vh = −60 mV; light intensity of 2.39 × 1015 photons × cm−2 × s−1).

In addition to capacitative Ca2+ entry, PLC-triggered pathways for calcium influx that are not dependent on the filling state of the intracellular calcium stores have also been described. Arachidonic acid can activate such noncapacitative Ca2+ influx in some cases (Shuttleworth, 1996). We tested stimulation of Lima microvillar photoreceptors with arachidonic acid either applied by local superfusion (10–50 µM; n = 9) or by internal dialysis (10 µM; n = 3). Such treatment, however, failed to elicit any discernible inward current. We also examined the possibility that calcium itself may be a triggering stimulus for Islow. To that end, we dialyzed elevated calcium into the cells (≈50 µM) but did not observe the spontaneous development of an inward current in the dark. Moreover, high intracellular calcium depressed Islow rather than potentiating it. Compared with control photoreceptors dialyzed with the standard internal solution, ≈50 µM [Ca2+]i reduced approximately by half the amplitude of Islow (119 ± 54 pA; n = 9). Thus, it seems unlikely that the rise in cytosolic Ca2+ levels directly controls Islow, a contention that would also be difficult to reconcile with the time course of this membrane current, which develops over many seconds, long after the increase in [Ca2+]i has substantially decayed.

DISCUSSION

The ubiquitous phosphoinositide signaling pathway (for review see Berridge and Irvine, 1989) underlies visual transduction in microvillar photoreceptors of invertebrates (Devary et al., 1987). According to the canonical scheme, the Ca2+ elevation that accompanies the photoresponse is initiated by release from internal InsP3-sensitive stores. Owing to the finite capacity of the calcium-containing organelles, such release cannot proceed indefinitely when a cell is challenged with strong or sustained stimulation. If the light-activated channels are permeable to calcium (Brown et al., 1971; Hardie, 1991), Ca signaling can be protracted simply via influx through the same ionic pathway that underlies the receptor potential. However, in several microvillar photoreceptors, the light-dependent conductance does not allow significant Ca2+ fluxes, an impasse that calls for ancillary mechanisms to aid the prolongation of the calcium response.

The present study was inspired by the observation that Lima microvillar photoreceptors exposed to strong photostimulation produce a receptor potential that is consistently followed by an after-depolarization lasting for >1 min (Nasi, 1991a); interestingly, Ca2+ does not permeate significantly through the light-dependent conductance of Lima photoreceptors (Gomez and Nasi, 1996). A similar slow after-depolarization had been noted in Apis (Baumann and Hadjilazaro, 1972). Our data demonstrate the presence of a separate, slowly activating ionic mechanism, Islow, which is only triggered with brief, saturating flashes, or with prolonged light stimulation, and is permeable to calcium ions. Measurements with fluorescent calcium probes show that, concomitantly with Islow, calcium is maintained at an elevated plateau for tens of seconds. From the time constant of the decay of the initial light-evoked transient of Ca2+ release, one would not anticipate such lingering calcium increase, which must therefore be attributed to Islow. Consequently, this conductance is ideally suited to help in the Ca-dependent regulation of the light transduction machinery under conditions when the process of internal release ceases. This differs from a mechanism previously described in the drone retina, in which the recovery of photo-induced depletion of sequestered calcium was aided by the application of sustained, dim illumination (Ziegler and Walz, 1990).

Coping with the need to mobilize calcium beyond the capacity of the intracellular stores is, of course, a challenge not unique to photoreceptors. In many other cells that rely on phosphoinositide signaling, after the initial Ca2+ release subsides a persistent influx of calcium through the plasma membrane is often evoked, which has been dubbed capacitative Ca entry (for review see Putney, 1990; Parekh and Penner, 1997). Additionally, Ca2+ influx can also occur through a pathway dependent on receptor activation, but not necessarily on the filling state of the stores (receptor-operated current; for review see Bolotina, 2008). In both cases, the exact mechanism that controls the gating remains elusive (Putney et al., 2001; Venkatachalam et al., 2002; Prakriya and Lewis, 2003), but it may involve a diffusible internal messenger (Parekh et al., 1993; Randriamampita and Tsien, 1993), direct conformational coupling between proteins (Luik et al., 2006), or the exocytotic fusion of channel-containing vesicles with the plasmalemma (Yao et al., 1999). The molecular search for some of the players has led to the identification of a candidate molecule for the role of ER luminal Ca2+ sensor, STIM1 (Roos et al., 2005), and a putative subunit of the calcium channel, Orai1 (Feske et al., 2006).

There are obvious similarities between Islow and depletion-activated currents, including the striking resemblance in time course and the conditions of stimulation under which it is elicited. However, other features of Islow are surprising, such as its amplitude, which, although ≈20-fold smaller than the photocurrent, is still quite considerable. In contrast, in a variety of other cells the currents associated with the late Ca2+ influx proved very difficult to measure electrophysiologically because of their minute size (typically only a few pA; e.g., Hoth and Penner, 1992; Bahnson et al., 1993). Two considerations could explain the large amplitude of Islow in Lima: (1) calcium transients in microvillar photoreceptors are the largest known, reaching amplitudes of tens of μM (Brown et al., 1977; Levy and Fein, 1985; Peretz et al., 1994; Ukhanov et al., 1995), and Lima is no exception. Although an absolute quantification is not possible without ratiometric measurements, large signals were obtained with a low-affinity dye (Ca Green 5N; KD ≈14 µM); moreover, signals recorded with higher affinity indicators such as Fluo 4 and Calcium Green 2 (KD ≈0.345 and ≈0.55 µM, respectively) had slower fall kinetics, suggestive of dye saturation (not depicted). Notice that all KD values quoted refer to the manufacturer specifications, measured in 100 mM KCl, but for all calcium indicators the affinity is known to decrease significantly in vivo and at higher values of ionic strength (the ionic strength of ASW is 1.35; Thomas et al., 2000). To the extent that a sizable fraction of such a massive load of released calcium is rapidly extruded by a Na/Ca exchanger (Minke and Armon, 1984; O'Day and Gray-Keller, 1989), the task of subsequently reestablishing homeostasis may require a correspondingly hefty pathway of Ca2+ influx. (2) The heavily invaginated rhabdomere provides abundant membrane area to accommodate a large number of transporting proteins (as gauged from the capacitance, which, at ≈70 pF, is severalfold larger than that of other cells of similar dimensions) (Nasi, 1991a). Together, these two factors could give rise to an unusually large current. This would make Lima photoreceptors an appealing model for the biophysical characterization of the slow Ca2+ influx, offering, in a native context, the size and reproducibility that in other cells have only been obtained by overexpression of STIM and Orai (Mercer et al., 2006; Peinelt et al., 2006; Soboloff et al., 2006).

However, differences between Islow and the classical capacitative calcium entry must not be disregarded. One is that thapsigargin, a SERCA inhibitor widely used to empty internal calcium stores and capable of mimicking physiologically induced SOCE, only elicited a very modest current. Independent evidence demonstrated that under those conditions the cells' ability to release calcium was severely compromised, suggesting that thapsigargin had indeed depleted calcium stores. An equally salient discrepancy is the lack of suppression of Islow by lanthanum and by SKF96365, two agents known to block capacitative Ca2+ entry. At this stage, therefore, Islow can be characterized as a conductance mediating a “late” Ca2+ influx, but it cannot unequivocally be grouped with SOCE. Other options should therefore not be discarded a priori. Prolonged afterpotentials induced by chromatic adaptation have been described in some invertebrate photoreceptors (prolonged depolarizing afterpotential; Hillman et al., 1983) and attributed to the accumulation of metarhodopsin (M) in species where its spectral absorption differs substantially from that of rhodopsin (R). However, prolonged depolarizing afterpotential is simply the prolongation of the photoresponse itself (due to arrestin saturation), not a separate, gradually developing process like Islow. Moreover, in Lima microvillar photoreceptors, the lack of aftereffects of intense chromatic stimulation suggests that there is no significant spectral shift in the transition R→M, and hence no likely accumulation of M that may trigger the observed outcome by some other means. In conclusion, Islow mediates a sustained influx of calcium that occurs under stimulation conditions that lead to calcium store depletion, and may thus serve the purpose of sustaining calcium signaling and/or aiding in the refilling of the intracellular stores. However, its regulation seems largely independent of the luminal levels of ER calcium. The large size and reproducibility of Islow make it a useful model system to investigate the control mechanism of receptor-operated currents, which at present remain poorly understood.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant 0639774.

Edward N. Pugh Jr. served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ASW

- artificial sea water

- Islow

- slow inward current

References

- Bahnson T.D., Pandol S.J., Dionne V.E. 1993. Cyclic GMP modulates depletion-activated Ca2+ entry in pancreatic acinar cells.J. Biol. Chem. 268:10808–10812 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann F., Hadjilazaro B. 1972. A depolarizing aftereffect of intense light in the drone visual receptor.Vision Res. 12:17–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann O., Walz B., Somlyo A.V., Somlyo A.P. 1991. Electron probe microanalysis of calcium release and magnesium uptake by endoplasmic reticulum in bee photoreceptors.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88:741–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J., Irvine R.F. 1989. Inositol phosphates and cell signalling.Nature. 341:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotina V.M. 2008. Orai, STIM1 and iPLA2β: a view from a different perspective.J. Physiol. 586:3035–3042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolsover S.R., Brown J.E. 1985. Calcium ion, an intracellular messenger of light adaptation, also participates in excitation of Limulus photoreceptors.J. Physiol. 364:381–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.E., Blinks J.R. 1974. Changes in intracellular free calcium concentration during illumination of invertebrate photoreceptors. Detection with aequorin.J. Gen. Physiol. 64:643–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.E., Lisman J.E. 1975. Intracellular Ca modulates sensitivity and time scale in Limulus ventral photoreceptors.Nature. 258:252–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.E., Mote M.I. 1974. Ionic dependence of reversal voltage of the light response in Limulus ventral photoreceptors.J. Gen. Physiol. 63:337–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.E., Rubin L.J. 1984. A direct demonstration that inositol-trisphosphate induces an increase in intracellular calcium in Limulus photoreceptors.Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 125:1137–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H.M., Hagiwara S., Koike H., Meech R.W. 1971. Electrical characteristics of a barnacle photoreceptor.Fed. Proc. 30:69–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.E., Brown P.K., Pinto L.H. 1977. Detection of light-induced changes of intracellular ionized calcium concentration in Limulus ventral photoreceptors using arsenazo III.J. Physiol. 267:299–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyb S., Raghu P., Hardie R.C. 1999. Polyunsaturated fatty acids activate Drosophila light-sensitive channels TRP and TRPL.Nature. 397:255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devary O., Heichal O., Blumenfeld A., Cassel D., Suss E., Barash S., Rubinstein C.T., Minke B., Selinger Z. 1987. Coupling of photoexcited rhodopsin to inositol phospholipid hydrolysis in fly photoreceptors.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:6939–6943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J.S., Palade P. 1998. Perforated patch recording with beta-escin.Pflugers Arch. 436:1021–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein A., Payne R., Corson W.D., Berridge M.J., Irvine R.F. 1984. Photoreceptor excitation and adaptation by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate.Nature. 311:157–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S.-H., Tanasa B., Hogan P.G., Lewis R.S., Daly M., Rao A. 2006. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function.Nature. 441:179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M.D., Nasi E. 1996. Ion permeation through light-activated channels in rhabdomeric photoreceptors. Role of divalent cations.J. Gen. Physiol. 107:715–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez M., Nasi E. 1998. Membrane current induced by protein kinase C activators in rhabdomeric photoreceptors: implications for visual excitation.J. Neurosci. 18:5253–5263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie R.C. 1991. Whole-cell recordings of the light induced current in dissociated Drosophila photoreceptors: evidence for feedback by calcium permeating the light-sensitive channels.Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 245:203–210 [Google Scholar]

- Hardie R.C. 1996. INDO-1 measurements of absolute resting and light-induced Ca2+ concentration in Drosophila photoreceptors.J. Neurosci. 16:2924–2933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman P., Hochstein S., Minke B. 1983. Transduction in invertebrate photoreceptors: role of pigment bistability.Physiol. Rev. 63:668–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R., Marty A. 1988. Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured by a new whole-cell recording method.J. Gen. Physiol. 92:145–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth M., Penner R. 1992. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells.Nature. 355:353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S., Fein A. 1985. Relationship between light sensitivity and intracellular free Ca concentration in Limulus ventral photoreceptors. A quantitative study using Ca-selective microelectrodes.J. Gen. Physiol. 85:805–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luik R.M., Wu M.M., Buchanan J., Lewis R.S. 2006. The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER-plasma membrane junctions.J. Cell Biol. 174:815–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J.C., Dehaven W.I., Smyth J.T., Wedel B., Boyles R.R., Bird G.S., Putney J.W., Jr 2006. Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1.J. Biol. Chem. 281:24979–24990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millecchia R., Mauro A. 1969. The ventral photoreceptor cells of Limulus: III. A voltage-clamp study.J. Gen. Physiol. 54:331–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minke B., Armon E. 1984. Activation of electrogenic Na-Ca exchange by light in fly photoreceptors.Vision Res. 24:109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpitsos G.J. 1973. Physiology of vision in the mollusk Lima scabra.J. Neurophysiol. 36:371–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasi E. 1991a. Electrophysiological properties of isolated photoreceptors from the eye of Lima scabra.J. Gen. Physiol. 97:17–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasi E. 1991b. Whole-cell clamp of dissociated photoreceptors from the eye of Lima scabra.J. Gen. Physiol. 97:35–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasi E. 1991c. Two light-dependent conductances in Lima rhabdomeric photoreceptors.J. Gen. Physiol. 97:55–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Day P.M., Gray-Keller M.P. 1989. Evidence for electrogenic Na+/Ca2+ exchange in Limulus ventral photoreceptors.J. Gen. Physiol. 93:473–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh A.B., Penner R. 1997. Store depletion and calcium influx.Physiol. Rev. 77:901–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh A.B., Terlau H., Stühmer W. 1993. Depletion of InsP3 stores activates a Ca2+ and K+ current by means of a phosphatase and a diffusible messenger.Nature. 364:814–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne R., Fein A. 1986. The initial response of Limulus ventral photoreceptors to bright flashes. Released calcium as a synergist to excitation.J. Gen. Physiol. 87:243–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne R., Corson D.W., Fein A. 1986. Pressure injection of calcium both excites and adapts Limulus ventral photoreceptors.J. Gen. Physiol. 88:107–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinelt C., Vig M., Koomoa D.L., Beck A., Nadler M.J.S., Koblan-Huberson M., Lis A., Fleig A., Penner R., Kinet J.-P. 2006. Amplification of CRAC current by STIM1 and CRACM1 (Orai1).Nat. Cell Biol. 8:771–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz A., Suss-Toby E., Rom-Glas A., Arnon A., Payne R., Minke B. 1994. The light response of Drosophila photoreceptors is accompanied by an increase in cellular calcium: effects of specific mutations.Neuron. 12:1257–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakriya M., Lewis R.S. 2003. CRAC channels: activation, permeation, and the search for a molecular identity.Cell Calcium. 33:311–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney J.W., Jr. 1990. Capacitative calcium entry revisited.Cell Calcium. 11:611–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney J.W., Jr., Broad L.M., Braun F.-J., Lievremont J.-P., Bird G.S.J. 2001. Mechanisms of capacitative calcium entry.J. Cell Sci. 114:2223–2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randriamampita C., Tsien R.Y. 1993. Emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores releases a novel small messenger that stimulates Ca2+ influx.Nature. 364:809–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan R., Bacskai B.J., Tsien R.Y., Zuker C.S. 1994. Cytosolic calcium transients: spatial localization and role in Drosophila photoreceptor cell function.Neuron. 13:837–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J., DiGregorio P.J., Yeromin A.V., Ohlsen K., Lioudyno M., Zhang S., Safrina O., Kozak J.A., Wagner S.L., Cahalan M.D., et al. 2005. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function.J. Cell Biol. 169:435–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J., Richard E.A., Lisman J.E. 1993. Ca2+ is an obligatory intermediate in the excitation cascade of limulus photoreceptors.Neuron. 11:845–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth T.J. 1996. Arachidonic acid activates the noncapacitative entry of Ca2+ during [Ca2+]i oscillations.J. Biol. Chem. 271:21720–21725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soboloff J., Spassova M.A., Tang X.D., Hewavitharana T., Xu W., Gill D.L. 2006. Orai1 and STIM reconstitute store-operated calcium channel function.J. Biol. Chem. 281:20661–20665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D., Tovey S.C., Collins T.J., Bootman M.D., Berridge M.J., Lipp P. 2000. A comparison of fluorescent Ca2+ indicator properties and their use in measuring elementary and global Ca2+ signals.Cell Calcium. 28:213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukhanov K.Y., Flores T.M., Hsiao H.-S., Mohapatra P., Pitts C.H., Payne R. 1995. Measurement of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in Limulus ventral photoreceptors using fluorescent dyes.J. Gen. Physiol. 105:95–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K., van Rossum D.B., Patterson R.L., Ma H.-T., Gill D.L. 2002. The cellular and molecular basis of store-operated calcium entry.Nat. Cell Biol. 4:E263–E272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner U., Suss-Toby E., Rom A., Minke B. 1992. Calcium is necessary for light excitation in barnacle photoreceptors.J. Comp. Physiol. A. 170:427–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Ferrer-Montiel A.V., Montal M., Tsien R.Y. 1999. Activation of store-operated Ca2+ current in Xenopus oocytes requires SNAP-25 but not a diffusible messenger.Cell. 98:475–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler A., Walz B. 1990. Evidence for light-induced release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in bee photoreceptors.Neurosci. Lett. 111:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]