Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease of the motor system. Recent work in rodent models of ALS has shown that insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) slows disease progression when delivered at disease onset. However, IGF-1’s mechanism of action along the neuromuscular axis remains unclear. In this study, symptomatic ALS mice received IGF-1 through stereotaxic injection of an IGF-1-expressing viral vector to the deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN), a region of the cerebellum with extensive brain stem and spinal cord connections. We found that delivery of IGF-1 to the central nervous system (CNS) reduced ALS neuropathology, improved muscle strength, and significantly extended life span in ALS mice. To explore the mechanism of action of IGF-1, we used a newly developed in vitro model of ALS. We demonstrate that IGF-1 is potently neuroprotective and attenuates glial cell–mediated release of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and nitric oxide (NO). Our results show that delivering IGF-1 to the CNS is sufficient to delay disease progression in a mouse model of familial ALS and demonstrate for the first time that IGF-1 attenuates the pathological activity of non-neuronal cells that contribute to disease progression. Our findings highlight an innovative approach for delivering IGF-1 to the CNS.

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by a loss of motor neurons in the motor cortex, brain stem, and spinal cord. Approximately 20% of diagnosed familial cases of ALS are due to dominantly inherited mutations in superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1).1 Transgenic mice that express the mutant human SOD1 protein recapitulate many pathological features of ALS and are currently the best available animal model to study the disease.2

Trophic factors, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), have potent effects on motor neuron survival and have been investigated extensively as potential treatments for ALS.3–5 Recently, it has been shown that simultaneous delivery of IGF-1 to the neuromuscular junction, muscle, and spinal cord by intramuscular injection of an IGF-1-expressing viral vector leads to extended survival in SOD1G93A mice.6 Although it is evident from this experiment that IGF-1 is beneficial, it is difficult to conclude which component of the neuromuscular axis IGF-1 is primarily acting on to delay disease progression. Interestingly, existing evidence suggests that muscle may be the principle target of IGF-1 as double transgenic SOD1G93A and MLC/mIgf-1 mice show improved survival.7

The mechanism by which IGF-1 slows disease progression when delivered at the time of disease onset remains unclear. It is likely that IGF-1 is delaying motor neuron cell death through the stimulation of antiapoptotic pathways. However, it is also possible that IGF-1 may be attenuating the pathological activity of non-neuronal cells (i.e., astrocytes and microglia) that have been reported to modulate both disease onset and progression in ALS mice.8,9

In this study, we report that central nervous system (CNS)-restricted delivery of IGF-1 is sufficient to modify disease progression in ALS mice. We demonstrate that delivery of AAV-IGF-1 vectors to the deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN) of symptomatic SOD1G93A mice resulted in axonal transport of vector and/or expressed IGF-1 protein throughout the brain stem and spinal cord.10–14 Concomitant with IGF-1 expression within the CNS was a profound reduction in neuropathology throughout the CNS, increased motor neuron survival, improved motor function, and a significant extension of life span. In addition, the results of our in vitro studies indicate that IGF-1 may be delaying disease progression through attenuation of glial cell–mediated release of factors [i.e., tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and nitric oxide (NO)] known to initiate motor neuron cell death.

RESULTS

Distribution of IGF-1 in the CNS after the administration of AAV-IGF-1 to the DCN

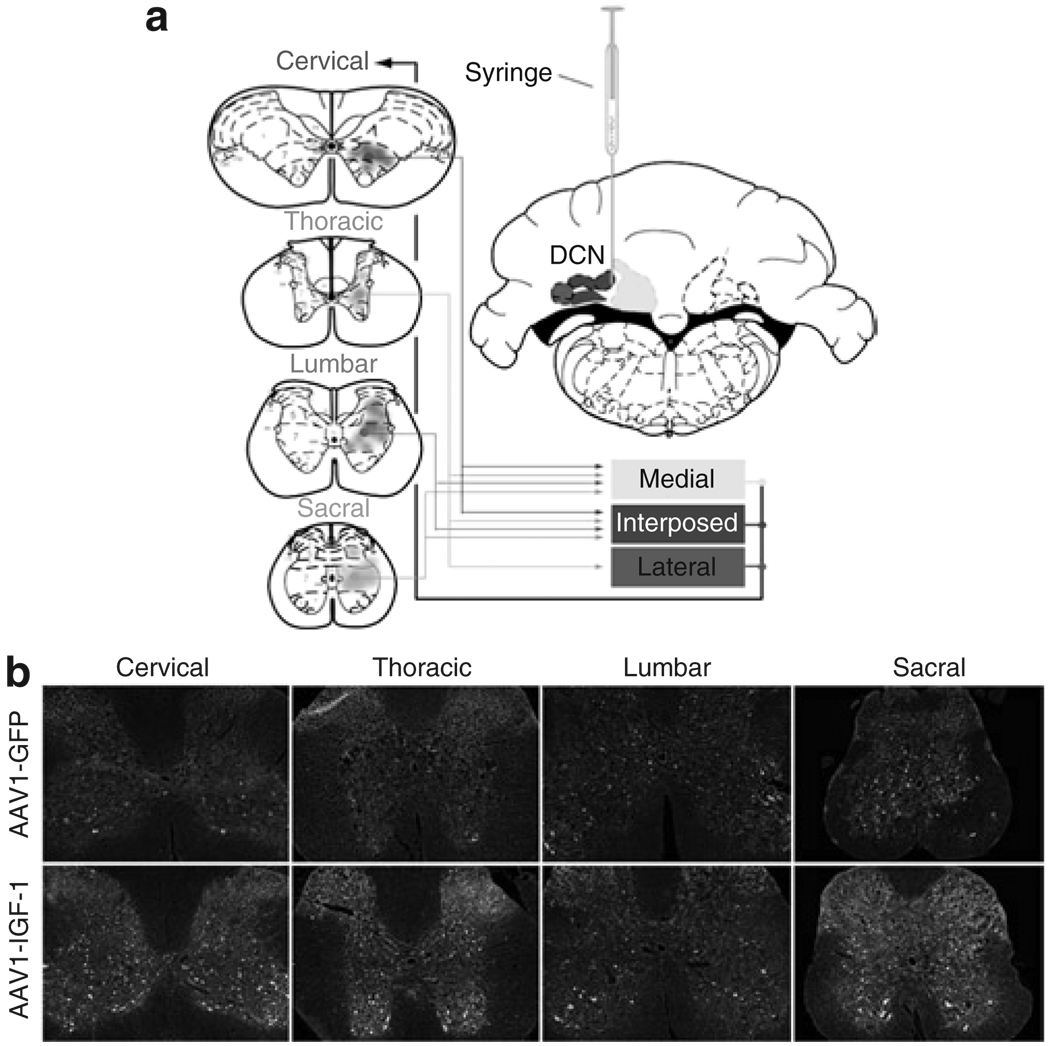

Figure 1a illustrates the connections between the DCN and the spinal cord. The medial and interposed nuclei receive input from each division of the spinal cord whereas the lateral nucleus receives input primarily from the thoracic division.10,12,13,15,16 All of the cerebellar nuclei have been reported to send input to the cervical division of the spinal cord.14 To determine the potential for targeting multiple regions of the CNS via the afferent and efferent projection pathways of the DCN, we tested two adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes, AAV2 and AAV1. AAV2 was chosen because most clinical studies to date have used this serotype vector. AAV1 was selected because it has been previously demonstrated to express high levels of transgenes in the brain.17,18 We stereotaxically injected 2 × 1010 DNase resistant particles (DRP) of AAV1-IGF-1 into the DCN of 90-day-old SOD1G93A mice and evaluated IGF-1 expression 20 days after injection. Positive IGF-1 signal was observed throughout the hindbrain, brain stem, and spinal cord after bilateral delivery of the IGF-1-expressing AAV vectors to the DCN. Positive IGF-1 staining was detected in the cerebellar cortex, brain stem (i.e., pontine nucleus, facial nucleus, locus ceruleus, and vestibular nuclei), and spinal cord. Within the spinal cord (Figure 1b), positive IGF-1 staining was most widely distributed within the cervical and thoracic divisions with detectable expression found in the lumbar and sacral regions, demonstrating that IGF-1 was expressed in all regions of the spinal cord at levels that may provide trophic support to motor neurons.

Figure 1. Delivery of viral vectors capable of axonal transport results in transgene delivery throughout the spinal cord.

(a) Diagram illustrating afferent and efferent connections between the deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN) and spinal cord. The DCN is composed of three separate nuclei: the lateral (orange), interposed (purple), and medial (yellow). The medial and interposed nuclei receive input from every region (i.e., cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral) of the spinal cord whereas the lateral receives input only from the thoracic division. All the three nuclei send projections to the cervical division of the spinal cord. Bilateral stereotaxic injections of viral vectors were made between the medial and interposed nuclei. (b) Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) staining in AAV-GFP- and AAV-IGF-1-treated mice throughout each segment of the spinal cord. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein. This figure is available in color in the online version of the article.

Delivery of AAV-IGF-1 to the DCN resulted in motor neuron protection and increased life span

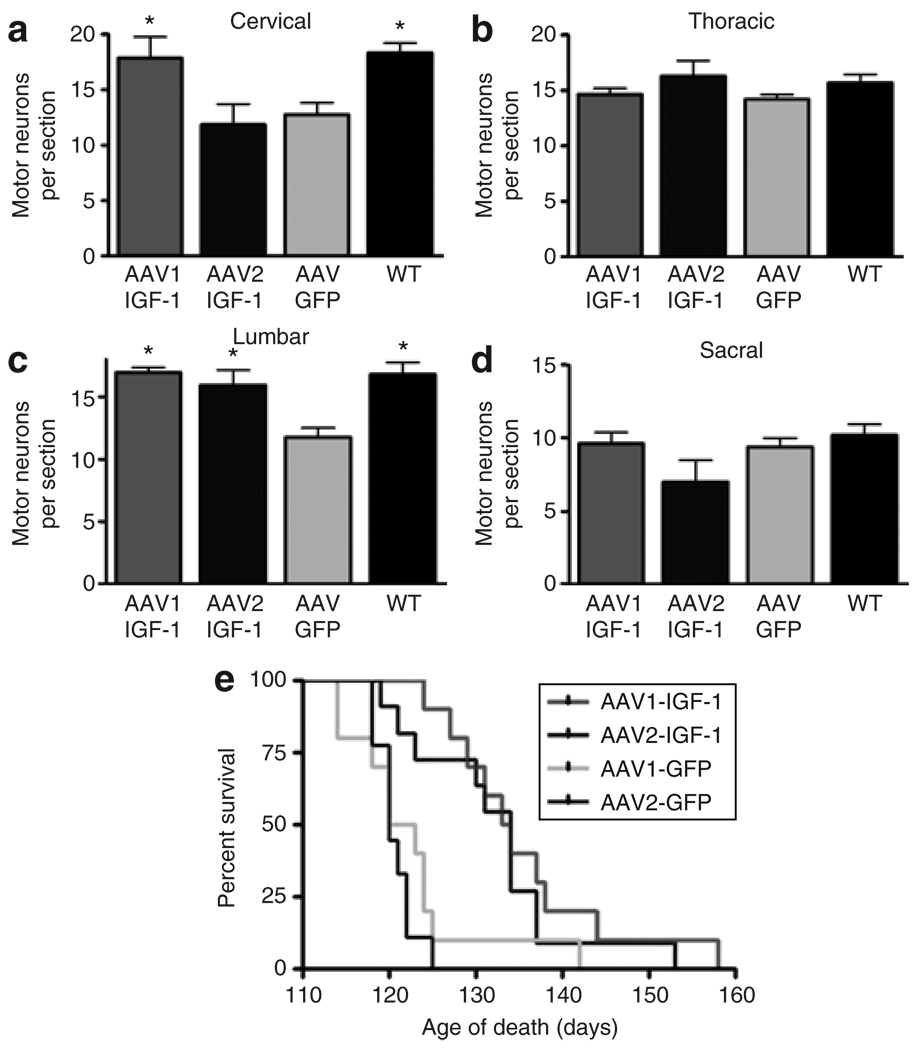

AAV1-IGF-1 and AAV2-IGF-1 were tested for their ability to enhance motor neuron survival in SOD1G93A mice compared with control AAV1-GFP and AAV2-GFP when injected at disease onset (88–90 days old). All regions of the spinal cord were evaluated at 110 days of age for the number of ChAT positive cells. AAV1-IGF-1-treated animals (17.86 ± 1.91) showed a significant (P < 0.01) preservation of motor neurons in the cervical region of the spinal cord compared with AAV2-IGF-1-treated mice (11.8 ± 1.83) or AAV-GFP-treated controls (12.74 ± 1.08) (Figure 2a). Both AAV1-IGF-1- (19.96 ± 0.39) and AAV2-IGF-1-treated animals (15.94 ± 1.21) displayed significantly (P < 0.01) higher numbers of motor neurons per section compared with AAV-GFP-treated animals (11.74 ± 0.762) in the lumbar region of the spinal cord (Figure 2c). There was no difference in the mean numbers of ChAT-positive cells between AAV1-IGF-1- and AAV-GFP-treated animals in the thoracic or sacral regions of the spinal cord at this time point (Figure 2b and d).

Figure 2. AAV-IGF-1-promoted motor neuron survival and delayed death in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice.

Motor neuron counts in (a) cervical, (b) thoracic, (c) lumbar, and (d) sacral regions of the spinal cord. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of AAV1-IGF-1-, AAV2-IGF-1-, AAV1-GFP-, and AAV2-GFP-treated animals (e). Mice were scored as dead when they could no longer right themselves within 30 seconds of being placed on their back. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-treated mice are indicated in green and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-treated mice are indicated in red. AAV, adeno-associated virus; WT, wild type.

In a separate cohort of animals, survival was assessed by Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Figure 2e). AAV-IGF-1 delivered to the DCN resulted in an ~14-day increase in median survival compared with AAV-GFP-treated animals (n = 25 animals/group, χ2 = 17.16, P = 0.0007). Median survival of AAV1-IGF-1-treated animals was similar to AAV2-IGF-1-treated animals (133.5 days versus 134 days, respectively) and the median survival of AAV1-GFP- and AAV2-GFP-treated animals was comparable (121.5 days versus 120 days). There was no difference in survival between untreated controls and AAV-GFP-treated animals (data not shown).

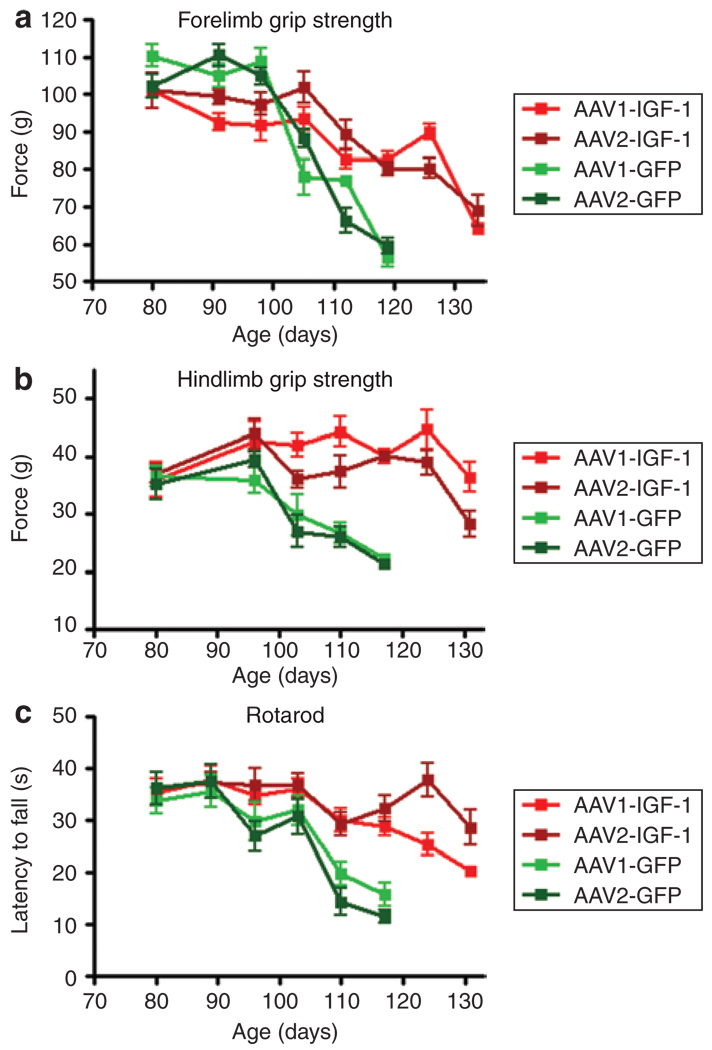

Functional benefits of DCN delivery of AAV-IGF-1

A battery of motor function tests was used to monitor disease progression. Forelimb grip strength measurements demonstrated that AAV-IGF-1-treated animals maintained statistically (P < 0.05) greater grip strength from 103 days of age through 131 days of age compared with those administered AAV-GFP (Figure 3a). In addition, animals treated with IGF-1 showed remarkable, statistically significant (P < 0.05) increases in hindlimb grip strength (Figure 3b). Rotarod tests also demonstrated that AAV-IGF-1-treated animals maintained their ability to coordinate their movement for a longer period than AAV-GFP-treated animals from 110 days of age until end stage (P < 0.05 from 110 days of age onward, n = 25 animals/group). In all of the motor function tests, there were no statistical differences observed between animals treated with AAV1-IGF-1 and AAV2-IGF-1 other than one time point at 124 days of age in the rotarod test (Figure 3c).

Figure 3. AAV-IGF-1 significantly prolonged motor function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice.

Mice were tested weekly for (a) forelimb grip strength, (b) hindlimb grip strength, and (c) rotarod coordination. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-treated mice had increased performance compared with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-treated mice. GFP-treated mice are indicated in green and IGF-1 treated mice are indicated in red. AAV, adeno-associated virus.

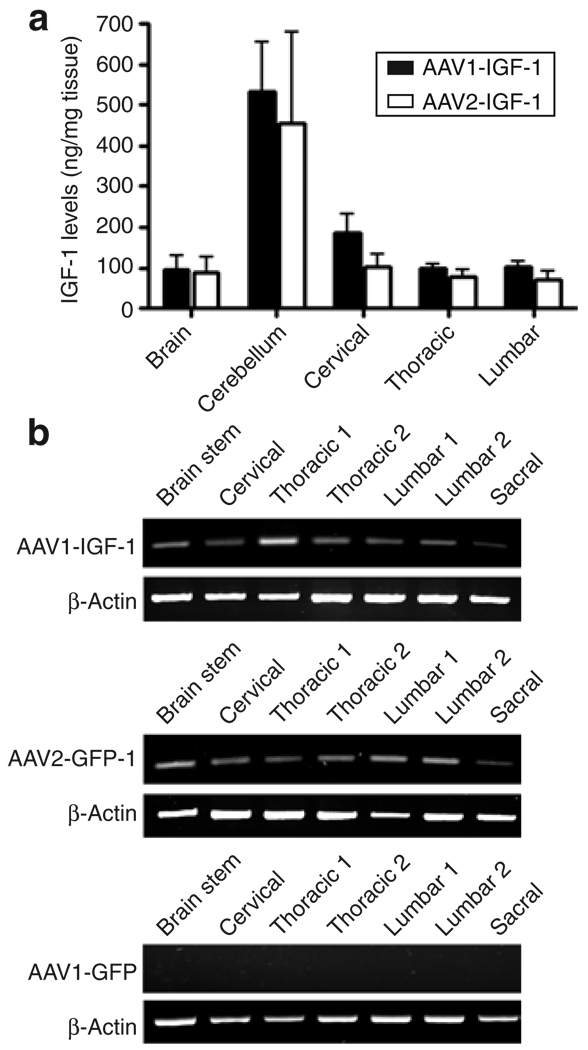

IGF-1 was detected throughout the brain and spinal cord of AAV-IGF-1-treated mice

To determine whether IGF-1 was expressed at similar levels by the two serotype vectors, we measured the levels of the trophic factor using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay that recognized the expressed human IGF-1 and not the endogenous murine counterpart. Detectable levels of human IGF-1 were noted in all of the regions of the brain and spinal cord of mice injected with AAV-IGF-1. Highest levels were found in the cerebellum and cervical region of the spinal cord, which were at or near the site of injection with no statistical differences between AAV1 and AAV2 (Figure 4a). No IGF-1 was detected in the serum of AAV-IGF-1-treated animals, indicating that the IGF-1 delivery was not systemic. Little to no IGF-1 was detected in green fluorescent protein (GFP)-treated animals, with background levels detected <20 ng/mg (data not shown).

Figure 4. Deep cerebellar nuclei delivery of AAV-IGF-1 resulted in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) expression in all regions of the spinal cord along with retrograde transport of vector to various regions of the spinal cord.

(a) Human IGF-1 levels in homogenates of various regions of the central nervous system were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (b) Retrograde transport of the viral vectors was detected by reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis of various regions of the spinal cord and brain after administrating AAV1-IGF-1 and AAV2-IGF-1. Control AAV1-GFP-treated mice showed no expression of the human IGF-1 transcript. AAV, adeno-associated virus.

To determine whether IGF-1 detected at locations distal to the site of injection resulted at least in part from retrograde transport of the AAV vectors, IGF-1 mRNA levels were measured in different regions of the brain using reverse transcriptase-PCR. Our results demonstrated significant transport and expression of the IGF-1 transcript in all regions of the spinal cord including sites distal to the injection site, such as the lumbar and sacral regions of the spinal cord (Figure 4b). No IGF-1 mRNA was found either in the AAV1-GFP-treated (Figure 4b) or AAV2-GFP-treated animals (data not shown), or in the reverse transcriptase–minus controls. These results demonstrate that both the AAV1-IGF-1 and AAV2-IGF-1 vectors underwent retrograde transport to all regions of the spinal cord after DCN injection.

IGF-1-expressing AAV vectors reduced Als-associated neuropathology in sod1G93A mice

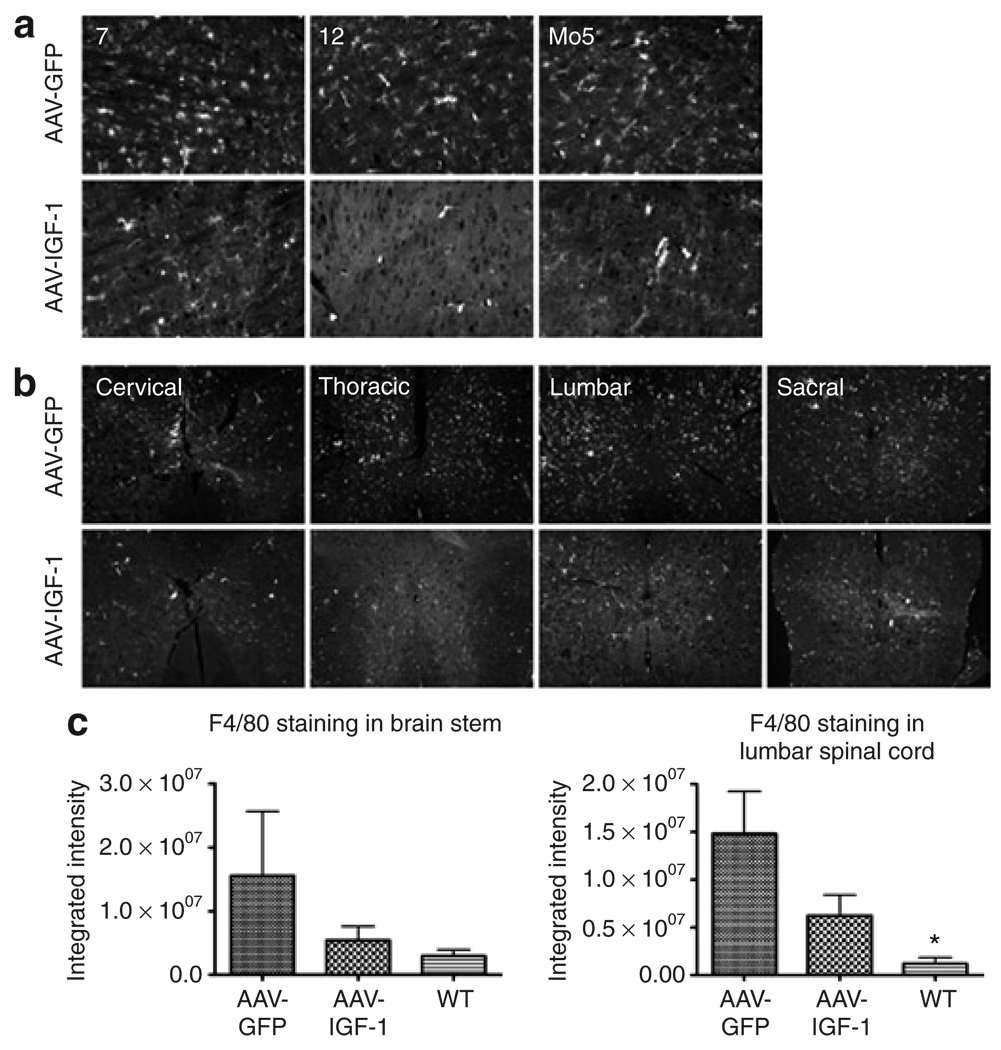

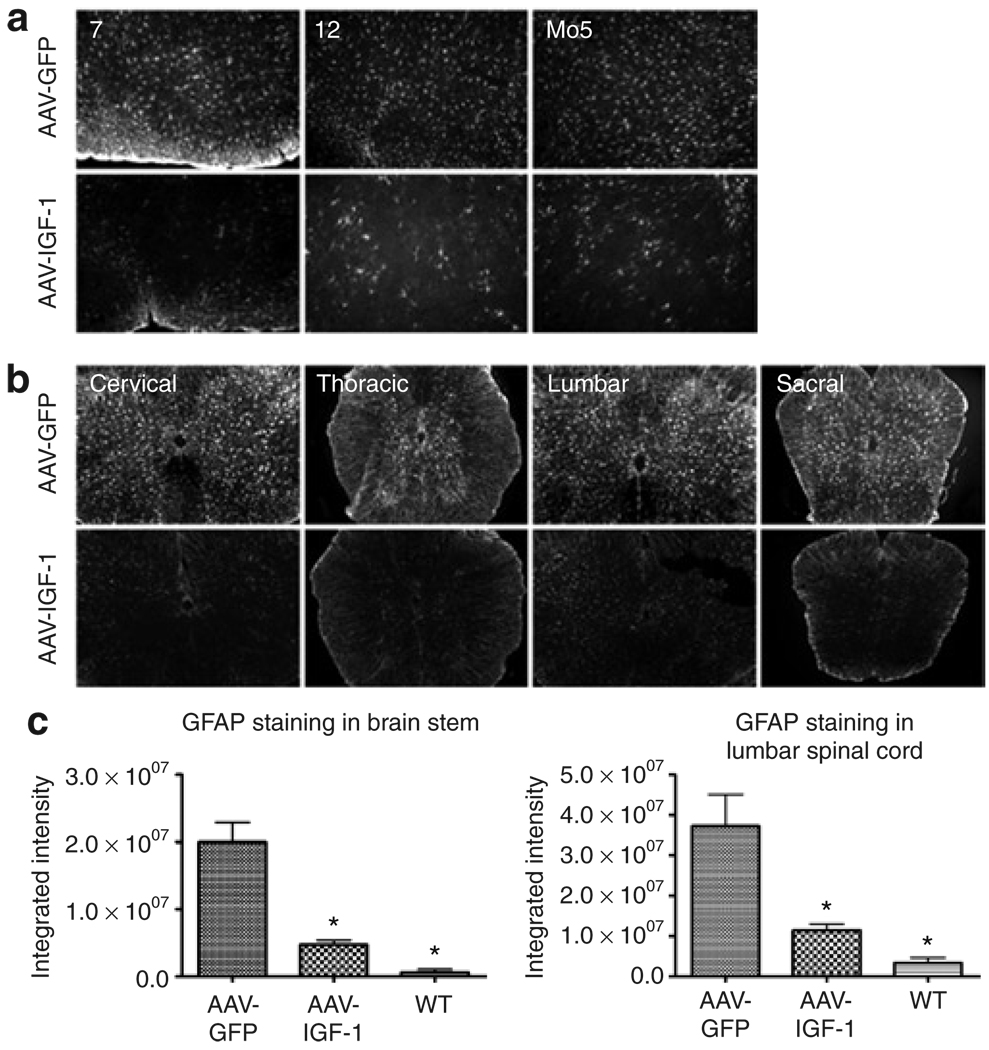

We next evaluated the ability of this therapy to attenuate the neuropathological features characteristic of ALS disease. Activated microglia and astrocytes contribute to the propagation of the disease process in ALS.4 Widespread gliosis is readily apparent in the brain stem and spinal cord of both human ALS patients and mouse models of the disease.19,20 In addition, biochemical assays and gene expression profiling studies showed that inflammatory cascades are activated before and during motor neuron degeneration.21,22 Microglial activation, astrogliosis, NO synthase expression, and peroxynitrite levels were assessed in mice treated with the AAV-IGF-1 and AAV-GFP vectors. MetaMorph analysis of our results showed that delivering AAV-IGF-1 to the DCN led to a reduction in gliosis both within the brain stem and throughout the spinal cord at 110 days of age compared with AAV-GFP-treated animals. Markers of microglial activation (F4/80 staining) and astrogliosis (glial fibrillary acidic protein staining) were diminished throughout the brain stem, including the motor trigeminal, hypoglossal, and facial nuclei (Figures 5a and c and Figures 6a and c). Throughout the entire length of the spinal cord, microglial activation and astrogliosis were also dramatically reduced (Figures 5b and c and Figures 6b and c).

Figure 5. AAV-IGF-1 attenuated microglial activation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mice.

Microglial activation (F4/80 staining) in the (a) brain stem (7 = facial nucleus, 12 = hypoglossal nucleus, and Mo5 = motor trigeminal nucleus) and (b) spinal cord in 110-day-old superoxide dismutase-1 mice that were treated with either AAV-GFP or AAV-IGF-1 at 90 days of age. (c) MetaMorph analysis of F4/80-stained brain stem and spinal cord sections taken from ALS mice treated with either AAV-IGF-1 or AAV-GFP and wild-type (WT) controls. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein; IGF, insulin-like growth factor.

Figure 6. AAV-IGF-1 significantly attenuated astrogliosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mice.

Astrogliosis [glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) staining] in the (a) brain stem (7 = facial nucleus, 12 = hypoglossal nucleus, and Mo5 = motor trigeminal nucleus) and (b) spinal cord in 110 day old superoxide dismutase-1 mice that were treated with either AAV-GFP or AAV-IGF-1 at 90 days of age. (c) MetaMorph analysis of GFAP-stained brain stem and spinal cord sections taken from ALS mice treated with either AAV-IGF-1 or AAV-GFP (P < 0.05) and wild-type (WT) controls. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein; IGF, insulin-like growth factor.

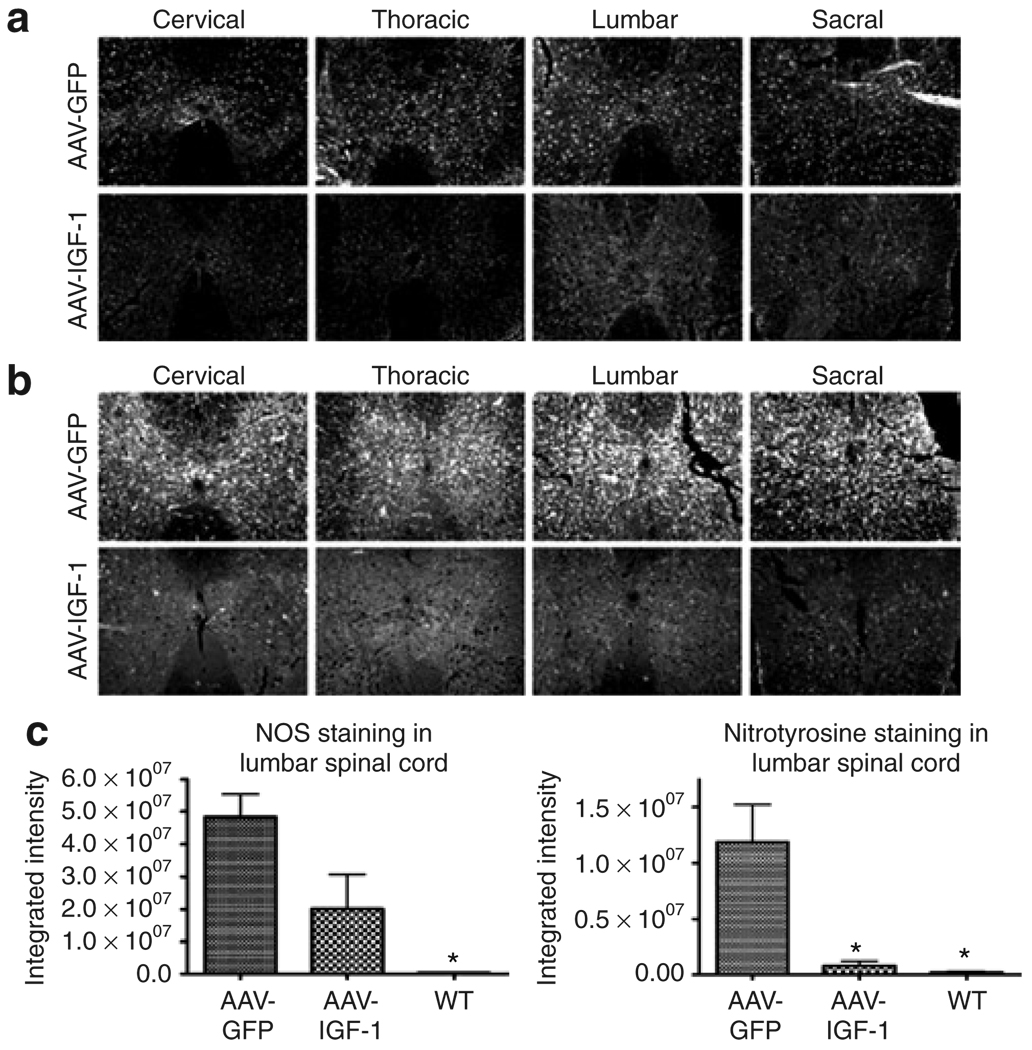

NO has been implicated as a contributing factor to the pathogenesis of ALS.23 Upregulation of NO has been shown to be involved in initiating Fas-triggered cell death, a programmed cell death pathway that appears to be restricted to motor neurons.24 Elevated NO has also been linked to the generation of peroxynitrite, formed by the reaction of NO with superoxide anions, resulting in the nitration of tyrosine residues in neurofilaments. This, in turn, causes irreversible inhibition of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, and inhibition of glutamate transporter activity. 25 Moreover, increased 3-nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity (a marker of peroxynitrite) has been reported in the spinal cord of both sporadic and familial ALS patients.26 Similar elevations in 3-nitrotyrosine have also been observed in the CNS of ALS mouse models.27,28 MetaMorph analysis of our results showed that delivery of IGF-1 resulted in reductions in the levels of both NO synthase (Figure 7a and c) and 3-nitrotyrosine (Figure 7b and c) throughout the spinal cord.

Figure 7. AAV-IGF-1 treatment reduced disease-induced elevations in nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity and peroxynitrite formation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mice.

(a) NOS and (b) 3-nitrotyrosine staining (peroxynitrite marker) in the spinal cord of 110-day-old superoxide dismutase-1 mice treated with either AAV-GFP or AAV-IGF-1 at 90 days of age. (c) MetaMorph analysis of NOS and 3-nitrotyrosinestained spinal cord sections taken from ALS mice treated with either AAV-IGF-1 or AAV-GFP (P < 0.05) and wild-type (WT) controls. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein; IGF, insulin-like growth factor.

IGF-1 is neuroprotective in coculture models of ALS and acts to inhibit microglial cell activation and astroglial toxicity

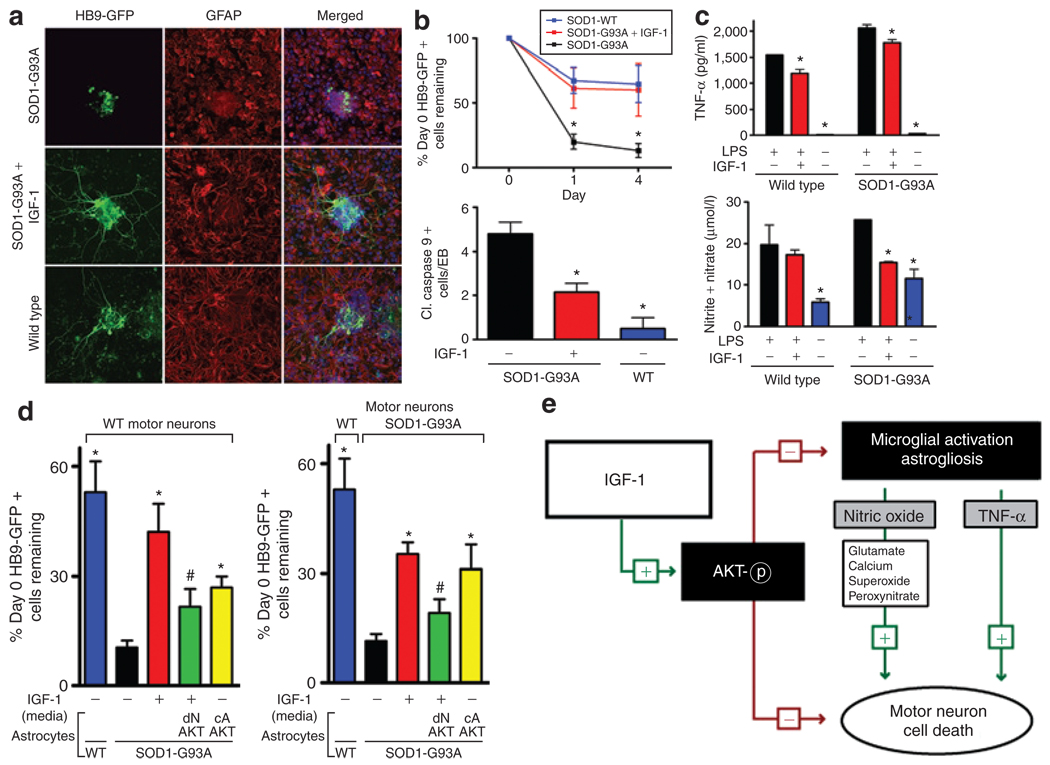

Recent studies using embryonic stem cell–derived motor neurons have demonstrated that in vitro models of ALS could be developed that mimic the motor neuron death seen in animal models of the disease.29,30 We developed similar models using embryonic stem cell–derived motor neurons containing the Hb9-GFP reporter that were transduced with a lentivirus containing the SOD1G93A gene or control SOD1WT. As previously shown, the mutation had minimal effects when expressed only in motor neurons.29,30 However, when motor neurons with or without the SOD1G93A gene were cocultured with astrocytes containing the SOD1G93A, motor neurons exhibited shorter axon lengths, increased cell death, and apoptosis shown by caspase-9 activation, which demonstrates and confirms that astrocytes expressing the mutant SOD1 are toxic to motor neurons (Figure 8a and b). To test whether IGF-1 could rescue the motor neuron toxicity, we replaced the medium from the SOD1G93A-expressing cocultures with either IGF-1-conditioned medium or mock-transfected control-conditioned medium and compared the results with wild-type cocultures. We observed significant rescue and neuroprotective effects of IGF-1 in coculture experiments with motor neurons and astrocytes both containing the SOD1G93A mutation, which was comparable to control wild-type cultures. IGF-1 treatment resulted in extensive preservation of neuritic extensions along with decreased caspase-9 activation indicating that IGF-1 was potently neuroprotective in this model (Figure 8a and b). We next sought to determine whether IGF-1 may be acting to delay glial cell activation, because earlier studies have demonstrated that glial cells containing the SOD1G93A mutation were a major contributor to disease progression and motor neuron death. We obtained the BV2 microglial cell line and transduced the cells using a lentivirus expressing wild-type SOD1 or SOD1G93A. Upon lipopolysaccharide induction, these cells produce high levels of TNF-α and NO. SOD1G93A microglia expressed higher levels of both TNF-α and NO compared with wild-type SOD1 microglia as previously demonstrated, suggesting that SOD1G93A mutation modestly activated these microglia. 31,32 Consistent with our earlier in vivo experiments, when BV2 microglial cells were cultured with IGF-1-conditioned media before lipopolysaccharide-mediated activation, IGF-1 significantly reduced TNF-α levels and completely suppressed the NO release to baseline levels of nonstimulated microglia, suggesting that IGF-1 directly attenuates microglial cell activation (Figure 8c).

Figure 8. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) rescues amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) motor neuron toxicity and attenuates glial activation and toxicity in an in vitro coculture model of ALS.

(a) SOD1-G93A motor neurons cultured with SOD1-G93A astrocytes in the presence of IGF-1 extend axons comparable to wild-type (WT) motor neurons cocultured with WT astrocytes. (b) SOD1-G93A motor neurons in a coculture with SOD1-G93A astrocytes survive longer with IGF-1 assessed by HB9-GFP counts and cleaved (cl.) caspase-9 + cells per embryoid body (EB) and compared to SOD1-WT motor neurons cultured with WT astrocytes. (c) SOD1-G93A microglia produce increased amounts of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and nitric oxide and IGF-1 attenuates the release of these factors. (d) Coculture of WT or SOD1-G93A motor neurons with WT or SOD1-G93A containing astroctyes in the presence of IGF-1-conditioned media and/or astrocytes expressing dominant negative (dN) AKT or constitutively active (cA) AKT demonstrates IGF-1’s neuroprotective ability and its actions on both motor neurons and astrocytes to protect motor neuron survival. (e) IGF-1 serves dual roles as an antiapoptotic factor and to block microglial activation and astrogliosis for motor neuron protection in ALS via activation of AKT. (*P < 0.05). GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; GFP, green fluorescent protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SOD1, superoxide dismutase-1.

We next tested the specific action of IGF-1 in our ALS-motor neuron/astrocyte coculture system using wild-type motor neurons or SOD1G93A motor neurons cocultured with SOD1G93A astrocytes. Because IGF-1 is a secreted molecule, it is difficult to test the effects of IGF-1 protein solely on motor neurons or astrocytes; hence, we utilized a signaling pathway of IGF-1 to test our hypothesis that IGF-1 was acting both on motor neurons and astrocytes for neuroprotection. IGF-1 is one of the most potent natural activators of the AKT signaling pathway. We confirmed that IGF-1 could activate AKT in astrocytes (data not shown) and therefore used an adenovirus encoding a constitutively activated AKT that was restricted to expression solely in astrocytes to mimic IGF-1 signaling. A dominant negative AKT adenovirus expressed only in astrocytes was also used as a negative control and as a control to inhibit IGF-1 signaling through AKT activation in astrocytes. As demonstrated in our earlier study, motor neurons with or without SOD1G93A perished when cultured on SOD1G93A astrocytes. IGF-1 added to the cultures significantly rescued the motor neurons from this toxicity. Interestingly, when motor neurons were cultured on top of SOD1G93A astrocytes expressing the constitutively activated AKT, there was significant protection of motor neurons compared with untreated (Figure 8d) or dominant negative AKT only expressing astrocytes (data not shown). To test whether IGF-1 signaling was required in astrocytes for motor neuron protection, a dominant negative AKT was expressed in astrocytes and IGF-1-conditioned media were added to the coculture. Blocking AKT signaling in astrocytes significantly reduced motor neuron survival, but did not completely abolish the neuroprotective effects of IGF-1, indicating that IGF-1 signaling to activate AKT acts on both motor neurons and astrocytes. These results suggest that IGF-1 signaling via AKT activation in astrocytes is sufficient in part to provide protection to motor neurons from astrocyte-derived toxicity and that there are additive effects of motor neuron protection by IGF-1 when both motor neurons and astroctyes are exposed to IGF-1.

DISCUSSION

Trophic factors such as IGF-1 have shown promise for the treatment of ALS.3–5 In this study, we report that CNS-restricted delivery of IGF-1 is sufficient to modify disease progression in symptomatic ALS mice. Specifically, we showed that injecting a recombinant AAV vector encoding IGF-1 within the DCN of SOD1G93A mice resulted in axonal transport of vector and/or expressed IGF-1 protein to the brain stem and all segments of the spinal cord. This, in turn, led to improved muscle function and a significant extension of life span. Furthermore, IGF-1 also attenuated astrogliosis, microglial activation, peroxynitrite formation, and glial cell–mediated release of TNF-α and NO.

Results obtained using mouse models of motor neuron disease have demonstrated that trophic factors (e.g., IGF-1, BDNF, CNTF, and GDNF) have potent effects on motor neuron survival.3–5 However, systemic administration of some of these recombinant trophic factors into subjects with ALS showed only very modest clinical benefit.33–36 Studies in ALS mice suggested that inadequate delivery of these trophic growth factors to the CNS may have been responsible for the poor response. Only systemic administration of vascular endothelial growth factor has been reported to be effective in treating SOD1G93A mice.37 Intrathecal administration of purified IGF-1 to the same mouse model was also efficacious.38 However, in both cases, positive effects were reported only when treatment was initiated in presymptomatic animals. In contrast to the results observed with systemic or intrathecal delivery of purified trophic factors, intramuscular injections of viral vectors encoding these factors demonstrated significant therapeutic benefit in the SOD1G93A mice, even when administered after the onset of overt disease symptoms.6,39 The results of this study indicate that trophic factor delivery to the CNS is sufficient to modify disease progression in symptomatic ALS mice. An advantage of this delivery strategy over existing approaches is that it permits the targeting of multiple areas that undergo neurodegeneration in ALS with a single injection site and obviates the need for injecting directly into the spinal cord where neurodegeneration is taking place. Comparison of survival benefits achieved with DCN versus intramuscular delivery of AAV-IGF-1 is difficult, given that a “death event” in an ALS mouse is artificially determined (i.e., occurs when the mouse can no longer right itself within 30 seconds). In the mouse model, testing a therapeutic is limited to measuring the ability to offer protection to motor neurons predominantly residing in the lumbar division of the spinal cord, which is responsible for the righting reflex. Indeed direct intraspinal injections of AAV-IGF-1 led to significant increases in survival.40 However, given that respiratory failure is the primary cause of death in ALS patients, we believe that delivering AAV-IGF-1 to the DCN may offer an advantage in that it permits targeting regions of the CNS that control respiration. This, in turn, may lead to a level of efficacy in ALS patients beyond what is observed in ALS mice.

Cellular mechanisms that modulate disease progression in ALS have not been known until just recently. While disease onset is initiated by motor neurons in ALS, it appears that glial cells modulate disease progression.8,9 The benefit provided by IGF-1 has mainly been thought to be attributable to activation of anti-apoptotic pathways (e.g., AKT and Bcl-2) within motor neurons of the spinal cord.41 However, efficacy is still observed when treatment is initiated during disease onset suggesting that the actions of IGF-1 may also be mediated through additional mechanisms, including muscle enhancement. While IGF-1 has potent effects on muscles, it has been recently demonstrated that muscle is not a direct target for mutant SOD1-mediated toxicity.42 Our in vivo studies here showed that IGF-1 may also attenuate a number of pathological features that have been linked to motor neuron cell death including increased NO activity, elevated peroxynitrite expression, astrogliosis, and microglial activation. Using a newly developed in vitro model of ALS, we corroborate our in vivo findings and also confirm earlier published results demonstrating that motor neurons containing the SOD1 mutation required coculture with astrocytes containing the SOD1 mutation for motor neuron death.29–31 To our knowledge, no study to date has compared the efficacy of a potential therapeutic such as IGF-1 in this in vitro ALS models system with efficacy results obtained using ALS mice. We show here that IGF-1 is potently neuroprotective when present in the coculture system. We observed a delay in neuritic atrophy, cell death, and caspase-9 activation in motor neurons treated with IGF-1. To decipher whether IGF-1 had effects on non-neuronal cells, we performed experiments using microglial cells that contained the mutant SOD1, because these cells have been directly linked to disease progression. Surprisingly, IGF-1 significantly lowered TNF-α and NO production when these cells were activated with lipopolysaccharide. Furthermore, we show here that the neuroprotective effects of IGF-1 are not exclusively limited to motor neurons in the coculture system, rather IGF-1 exerts strong inhibitory effects on SOD1G93A-mediated toxicity in astrocytes. These results strongly implicate that pleiotropic effects for IGF-1 in multiple non-neuronal subtypes of ALS suggested by the activation of AKT (Figure 8e) could be a potent neuroprotective factor for motor neurons along with the ability to attenuate aberrant glial cell activation and subsequent products produced by astrocytes and microglia, which have been implicated in ALS, such as glutamate, peroxynitrite, TNF-α, and NO. While not all of the signaling pathways of IGF-1 were evaluated in this coculture study, AKT activation appears to play a significant role in protecting motor neurons, in part by its actions for neuroprotection in motor neurons themselves, as well as suppressing the toxicity derived from SOD1G93A-containing astrocytes. This is of interest because it has recently been demonstrated that activated phosphorylated AKT is absent in motor neurons of both sporadic and familial ALS patients, and that motor neurons from mutant SOD1 mice lose activated AKT early in the disease.43 IGF-1 signaling through other signaling pathways may also be responsible in part for the effects on motor neuron protection.

In summary, these results highlight a novel approach to deliver IGF-1 to multiple regions of the CNS by a single injection site and show for the first time that CNS-restricted delivery of IGF is sufficient to modify disease progression in ALS mice. We also show that in addition to providing motor neuron protection, IGF-1 also modulates pathological events mediated by glial cells in ALS. These findings support the development of therapies that are designed to treat ALS by targeting motor neurons and their cellular environment. Furthermore, the data support the strength of developing therapeutic screens in the ALS coculture system and that potential future therapies may exploit the activation of AKT pathways in the CNS to curtail ALS progression.

METHODS

Animals

Transgenic male and female littermate mice that expressed the mutant SOD1G93A transgene at high levels were divided equally among groups. SOD1 gene copy number and SOD1 protein expression were confirmed with PCR and western blot analysis. Animals were housed under light/dark (12:12 hour) cycle and provided with food and water ad libitum. All procedures were performed using a protocol approved by the Columbus Children’s Research Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Stereotaxic surgery

Eighty-eight- to ninety-day-old mice anesthetized with isoflurane were bilaterally injected into the DCN (A–P: −5.75; M–L: −1.8; D–V: −2.6 from bregma and dura; incisor bar: 0.0) with 3 µl/site of AAV1-GFP (n = 26), AAV1-IGF-1 (n = 25), AAV2-GFP (n = 26), and AAV2-IGF-1 (n = 27) using a beveled 10-µl Hamilton syringe (rate of 0.5 µl/min for a total of 2.0 × 1010 DRP/injection site).17

Production of recombinant vectors

Recombinant AAV1 and AAV2 vectors were produced as described earlier.44,45 A contract manufacturing company (Virapur, San Diego, CA) was used for some virus preparations. Titers were determined to be 3 × 1012 DRP/ml using quantitative PCR. The cDNA for the human IGF-1 encoded the Class 1 IGF-1Ea with a portion of the 5′-untranslated region of IGF-1.6 The human cDNA for either wild-type or mutant G93A SOD1 was cloned into cytomegalovirus-based expression vector for lentiviral production by the quadruple plasmid trans-fection method with CaCl2.46

Reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis of IGF-1 mRNA and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of IGF-1

RNA was isolated as described earlier. No reverse transcriptase controls were performed to evaluate for DNA contamination with no detectable products (data not shown). Primers against the 5′-untranslated region of the rAAV transcript (5′-GTGGATCCTGAGAACTTCAG-3′) were used along with the 3′-primer (5′-ATTGGGTTGGAAGACTGCTG-3′), which is homologous to IGF-1 and PCR performed. Amplified products were confirmed by sequencing to be specific for the human IGF-1 transcript.

Protein was isolated by rapidly dissecting the spinal cord on ice and immediately homogenizing using Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) with Complete protease inhibitor (Roche, Palo Alto, CA). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for human IGF-1 were performed in quadruplicate using the Quantikine kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Protein homogenates were diluted 1,000-fold using the assay diluent and the assays performed following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Immunostaining

Brain and spinal cord sections from 110-day-old mice treated with AAV1-IGF-1, AAV2-IGF-1, and AAV-GFP (n = 8/group) were stained with rabbit anti-hIGF-1 antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-chAT antibody (1:500; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein antibody (1:2,500; Dako, Glostrup, Germany), rabbit anti-NO synthase antibody (1:1,000; Chemicon International), mouse anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (1:2,000; Upstate, Temecula, CA), or rat anti-F4/80 antibody (1:10; Genzyme, Cambridge, MA). Secondary antibodies used were donkey anti-species–specific antibodies conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate or Cy3. Sections were visualized using a Nikon Eclipse E800 fluorescent microscope and evaluated for the percent reduction in fluorescent deposits using a MetaMorph Image Analysis System (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA) as described earlier.17

Rotarod, grip strength, and survival analysis

Testing of motor function using rotarod and grip strength was performed as reported earlier. A “death event” was entered when animals could no longer “right” themselves within 30 seconds after the animal was placed on its back. “Death event” classification was performed by two individuals who were blinded to treatment during assessment.

In vitro ALS models

Mouse embryonic stem cells that express GFP driven by the Hb9 promoter (HBG3 cells, gift from Tom Jessell, Columbia University) were cultured on primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Chemicon International) and differentiated into motor neurons as described earlier.47 After 5 days of differentiation as embryoid bodies, ~50 embryoid bodies were infected with 2 × 109 viral particles of lentivirus expressing human SOD1G93A or wild-type SOD1.

Neural progenitors were harvested from the spinal cords of B6SJLTg (SOD1G93A) mice and wild-type B6SJL mice at 8 weeks of age by the Percoll density gradient centrifugation method as described earlier.48 Spinal cord progenitors were cultured on poly-ornithine-/laminin-coated plates in fibroblast growth factor/endothelial growth factor/heparin containing media as described. To induce astrocytic differentiation, fibroblast growth factor-2 and endothelial growth factor were removed and 10% fetal bovine serum was added to the media for 7 days. Twenty-four hours after infection of the motor neurons with lentivirus, motor neurons were plated on top of the astrocytes. In some experiments, astrocytes were infected 24 hours before starting the coculture with either Adenovirus-CMV-Akt1(Myr) (cA) or Adenovirus-CMV-Akt1 (dN) (Vector Biolabs, Philadelphia, PA) at 100 plaque forming units/cell. Before motor neurons were plated on the astrocytes, they were washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline and then allowed to incubate with fresh media for 30 minutes before motor neuron plating. The coculture of motor neurons and astrocytes was cultured in conditioned media from HEK293 cells transfected with either an IGF-1-expressing plasmid or mock-transfected and conditioned for 24 hours. The coculture media were replaced daily with fresh conditioned media. Cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked in 10% donkey serum with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with primary antibodies to guinea pig glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:1,000; Advanced ImmunoChemical, Long Beach, CA) and rat cleaved caspase-9 (1:100; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). All images were collected using a laser scanning confocal microscope while maintaining the same exposure time, magnification, and gain. For HB9-GFP + and cleaved caspase-9 + counts, embryoid bodies were selected at random for quantification.

BV2 microglia (gift of Dr Phil Popovich, Ohio State University) were plated at 100,000 cells/well to three wells of a six-well dish and infected with 1 × 109 viral particles of either wild-type- or G93A SOD1 expressing lentivirus in the presence of polybrene (4 ng/ml; Sigma, St Louis, MO). Two days after infection, the BV2 cells were analyzed for TNF-α and NO production. BV2 microglia expressing SOD1WT or SOD1G93A was serum-starved overnight and then treated for 30 minutes with conditioned media from HEK293 cells transfected with IGF-1 or mock transfected. BV2 cells were then stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (055:B5, 100 ng/ml; Sigma) and the media were harvested 5 hours after stimulation for the TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems) or 3 days after stimulation for the NO assay. Total NO levels were determined by measuring nitrite and nitrate levels which are the breakdown products of NO metabolism. Nitrate is converted to nitrite by nitrate reductase and total nitrite levels are measured by a colorimetric assay utilizing the Griess reaction (R&D Systems).

Statistics

Survival analysis was performed by Kaplan–Meier analysis which generates a χ2 value to test for significance. The Kaplan–Meier test was performed using the log-rank test equivalent to the Mantel–Haenszel test. In addition, two-tailed P values were calculated. When comparing survival curves, median survival times were calculated with a 95% confidence interval. All other statistical tests not involved in survival analysis were performed by multiway analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni post hoc analysis of mean differences between groups (GraphPad Prizm Software, San Diego, CA).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff at DCM and Virus Production for their technical support and Ron Scheule for help with proofreading the manuscript. This work was funded by Genzyme and in part by a National Institutes of Health, National Eye Institute grant no. EY018991, Project ALS and MDA to B.K.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosen DR. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;364:362. doi: 10.1038/364362c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seeburger JL, Springer JE. Experimental rationale for the therapeutic use of neurotrophins in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Neurol. 1993;124:64–72. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruijn LI, Miller TM, Cleveland DW. Unraveling the mechanisms involved in motor neuron degeneration in ALS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleveland DW, Rothstein JD. From Charcot to Lou Gehrig: deciphering selective motor neuron death in ALS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:806–819. doi: 10.1038/35097565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaspar BK, Llado J, Sherkat N, Rothstein JD, Gage FH. Retrograde viral delivery of IGF-1 prolongs survival in a mouse ALS model. Science. 2003;301:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1086137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobrowolny G, Giacinti C, Pelosi L, Nicoletti C, Winn N, Barberi L, et al. Muscle expression of a local Igf-1 isoform protects motor neurons in an ALS mouse model. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:193–199. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clement AM, Nguyen MD, Roberts EA, Garcia ML, Boillee S, Rule M, et al. Wild-type nonneuronal cells extend survival of SOD1 mutant motor neurons in ALS mice. Science. 2003;302:113–117. doi: 10.1126/science.1086071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boillee S, Yamanaka K, Lobsiger CS, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kassiotis G, et al. Onset and progression in inherited ALS determined by motor neurons and microglia. Science. 2006;312:1389–1392. doi: 10.1126/science.1123511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushita M, Yaginuma H. Projections from the central cervical nucleus to the cerebellar nuclei in the rat, studied by anterograde axonal tracing. J Comp Neurol. 1995;353:234–246. doi: 10.1002/cne.903530206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsushita M, Gao X. Projections from the thoracic cord to the cerebellar nuclei in the rat, studied by anterograde axonal tracing. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:409–421. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970929)386:3<409::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsushita M. Projections from the upper lumbar cord to the cerebellar nuclei in the rat, studied by anterograde axonal tracing. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412:633–648. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991004)412:4<633::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsushita M. Projections from the lowest lumbar and sacral-caudal segments to the cerebellar nuclei in the rat, studied by anterograde axonal tracing. J Comp Neurol. 1999;404:21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voogd J. Cerebellum. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic; 2004. pp. 205–231. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsushita M, Xiong G. Projections from the cervical enlargement to the cerebellar nuclei in the rat, studied by anterograde axonal tracing. J Comp Neurol. 1997;377:251–261. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970113)377:2<251::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsushita M, Ueyama T. Projections from the spinal cord to the cerebellar nuclei in the rabbit and rat. Exp Neurol. 1973;38:438–448. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(73)90166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodge JC, Clarke J, Song A, Bu J, Yang W, Taksir TV, et al. Gene transfer of human acid sphingomyelinase corrects neuropathology and motor deficits in a mouse model of Niemann-Pick type A disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17822–17827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509062102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein RL, Dayton RD, Leidenheimer NJ, Jansen K, Golde TE, Zweig RM. Efficient neuronal gene transfer with AAV8 leads to neurotoxic levels of tau or green fluorescent proteins. Mol Ther. 2006;13:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawamata T, Akiyama H, Yamada T, McGeer PL. Immunologic reactions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis brain and spinal cord tissue. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:691–707. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall ED, Oostveen JA, Gurney ME. Relationship of microglial and astrocytic activation to disease onset and progression in a transgenic model of familial ALS. Glia. 1998;23:249–256. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199807)23:3<249::aid-glia7>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshihara T, Ishigaki S, Yamamoto M, Liang Y, Niwa J, Takeuchi H, et al. Differential expression of inflammation- and apoptosis-related genes in spinal cords of a mutant SOD1 transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 2002;80:158–167. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elliott JL. Experimental models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 1999;6:310–320. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catania MV, Aronica E, Yankaya B, Troost D. Increased expression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase spliced variants in reactive astrocytes of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis human spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raoul C, Estevez AG, Nishimune H, Cleveland DW, deLapeyriere O, Henderson CE, et al. Motoneuron death triggered by a specific pathway downstream of Fas: Potentiation by ALS-linked SOD1 mutations. Neuron. 2002;35:1067–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urushitani M, Shimohama S. The role of nitric oxide in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2001;2:71–81. doi: 10.1080/146608201316949415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beal MF, Ferrante RJ, Browne SE, Matthews RT, Kowall NW, Brown RH., Jr Increased 3-nitrotyrosine in both sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:644–654. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cha CI, Chung YH, Shin CM, Shin DH, Kim YS, Gurney ME, et al. Immunocytochemical study on the distribution of nitrotyrosine in the brain of the transgenic mice expressing a human Cu/Zn SOD mutation. Brain Res. 2000;853:156–161. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrante RJ, Shinobu LA, Schulz JB, Matthews RT, Thomas CE, Kowall NW, et al. Increased 3-nitrotyrosine and oxidative damage in mice with a human copper/zinc superoxide dismutase mutation. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:326–334. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagai M, Re DB, Nagata T, Chalazonitis A, Jessell TM, Wichterle H, et al. Astrocytes expressing ALS-linked mutated SOD1 release factors selectively toxic to motor neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:615–622. doi: 10.1038/nn1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Giorgio FP, Carrasco MA, Siao MC, Maniatis T, Eggan K. Non-cell autonomous effect of glia on motor neurons in an embryonic stem cell-based ALS model. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:608–614. doi: 10.1038/nn1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YS, Martinez T, Deshpande DM, Drummond J, Provost-Javier K, Williams A, et al. Correction of humoral derangements from mutant superoxide dismutase 1 spinal cord. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:716–728. doi: 10.1002/ana.21034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao Q, Zhao W, Beers DR, Yen AA, Xie W, Henkel JS, et al. Mutant SOD1(G93A) microglia are more neurotoxic relative to wild-type microglia. J Neurochem. 2007;102:2008–2019. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borasio GD, Robberecht W, Leigh PN, Emile J, Guiloff RJ, Jerusalem F, et al. European ALS/IGF-I Study Group. A placebo-controlled trial of insulin-like growth factor-I in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1998;51:583–586. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasarkis E. A controlled trial of recombinant methionyl human BDNF in ALS: the BDNF Study Group (Phase III) Neurology. 1999;52:1427–1433. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller RG, Petajan JH, Bryan WW, Armon C, Barohn RJ, Goodpasture JC, et al. rhCNTF ALS Study Group. A placebo-controlled trial of recombinant human ciliary neurotrophic (rhCNTF) factor in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:256–260. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai EC, Felice KJ, Festoff BW, Gawel MJ, Gelinas DF, Kratz R, et al. The North America ALS/IGF-I Study Group. Effect of recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I on progression of ALS. A placebocontrolled study. Neurology. 1997;49:1621–1630. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.6.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng C, Nennesmo I, Fadeel B, Henter JI. Vascular endothelial growth factor prolongs survival in a transgenic mouse model of ALS. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:564–567. doi: 10.1002/ana.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagano I, Ilieva H, Shiote M, Murakami T, Yokoyama M, Shoji M, et al. Therapeutic benefit of intrathecal injection of insulin-like growth factor-1 in a mouse model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2005;235:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azzouz M, Ralph GS, Storkebaum E, Walmsley LE, Mitrophanous KA, Kingsman SM, et al. VEGF delivery with retrogradely transported lentivector prolongs survival in a mouse ALS model. Nature. 2004;429:413–417. doi: 10.1038/nature02544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lepore AC, Haenggeli C, Gasmi M, Bishop KM, Bartus RT, Maragakis NJ, et al. Intraparenchymal spinal cord delivery of adeno-associated virus IGF-1 is protective in the SOD1(G93A) model of ALS. Brain Res. 2007;1185:256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, et al. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller TM, Kim SH, Yamanaka K, Hester M, Umapathi P, Arnson H, et al. Gene transfer demonstrates that muscle is not a primary target for non-cell-autonomous toxicity in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19546–19551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609411103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dewil M, Lambrechts D, Sciot R, Shaw PJ, Ince PG, Robberecht W, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor counteracts the loss of phospho-Akt preceding motor neurone degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2007;33:499–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rabinowitz JE, Rolling F, Li C, Conrath H, Xiao W, Xiao X, et al. Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J Virol. 2002;76:791–801. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.791-801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snyder RO, Spratt SK, Lagarde C, Bohl D, Kaspar B, Sloan B, et al. Efficient and stable adeno-associated virus-mediated transduction in the skeletal muscle of adult immunocompetent mice. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:1891–1900. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.16-1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naldini L, Blomer U, Gage FH, Trono D, Verma IM. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11382–11388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wichterle H, Lieberam I, Porter JA, Jessell TM. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into motor neurons. Cell. 2002;110:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ray J, Gage FH. Differential properties of adult rat and mouse brain-derived neural stem/progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:560–573. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]