Abstract

Objectives

To study prospectively the differences in health inequality in men and women from 1986-96 using the Office for National Statistics' longitudinal study and new socioeconomic classification. To assess the relative importance of social class (based on employment characteristics) and social position according to the general social advantage of the household to mortality risk in men and women.

Design

Prospective study.

Setting

England and Wales.

Subjects

Men and women of working age at the time of the 1981 census, with a recorded occupation.

Main outcome measures

Mortality.

Results

In men, social class based on employment relations, measured according to the Office for National Statistics' socioeconomic classification, was the most important influence on mortality. In women, social class based on individual employment relations and conditions showed only a weak gradient. Large differences in risk of mortality in women were found, however, when social position was measured according to the general social advantage in the household.

Conclusions

Comparisons of the extent of health inequality in men and women are affected by the measures of social inequality used. For women, even those in paid work, classifications based on characteristics of the employment situation may give a considerable underestimate. The Office for National Statistics' new measure of socioeconomic position is useful for assessing health inequality in men, but in women a more important predictor of mortality is inequality in general social advantage of the household.

Introduction

Social variation in morbidity and mortality in women whose social position is measured according to their own occupation is often found to be less than that of men.1–4 The extent of social inequality in women's health is known to be particularly sensitive to the way in which inequality is defined and measured.1,5,6 When women's social position is classified according to the occupation of their male partners, male and female health gradients are more similar.7,8 In estimates of health inequality there is comparatively little discussion of these apparent sex differences.

It is now possible to study sex differences in health inequality with distinct validated measures of social position and advantage, one based on relations and conditions of employment and the other on material cultural aspects of lifestyle outside the workplace. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has recently adopted a new measure of social inequality: the ONS socioeconomic classification, for use in the 2001 census and official surveys.9 This measure allocates occupations to social classes on the basis of aspects of the work situation, in particular the extent to which members of an occupation have control over their own work and that of others.

The other measure is the Cambridge scale, which is based on general social and material advantage and lifestyle as reflected in choices of friendship.10–12 Both measures are being increasingly used in health studies and have been found to be related to mortality, morbidity, and health related behaviour.13–18

We aimed to determine whether social gradients in mortality in women in England and Wales during 1986-96 were less noticeable than in men, and whether this depended on the measure of social inequality used.

Subjects and methods

Sample

The ONS longitudinal study is an approximate 1% sample of the population of England and Wales. Sampling was begun at the time of the 1971 census when all those born on any one of four days in the year were entered into the dataset. The study is regularly updated to include new members born on any one of the four designated dates.19 Vital events including mortality are linked to the data from successive censuses. Aggregated data from the study are available to academics subject to strict controls to preserve confidentiality.19 For our study we included all those who were aged 16 to 65 (16 to 60 for women) and in paid work at the time of the 1981 census and who were still alive in 1986. Those who die within five years of a census are not included in mortality analyses of this dataset to reduce selection bias.20 Thus we included all cause mortality from 1986-96 in our analyses.

Measurement of social position

We used two measures of social position, the Cambridge scale and the ONS socioeconomic classification. These measures have been developed by research using explicit criteria.

ONS socioeconomic classification

This schema primarily distinguishes between employers and employees. Distinctions are made between employees whose work concerns higher and lower amounts of planning and supervision of their own work and that of others, degrees of job security, and the existence or not of a career structure.9 We used a seven category version of the ONS socioeconomic classification (table 1). Higher managers are those in establishments with more than 25 staff; lower managers are those in smaller establishments. Professional occupations are divided into employees who have total or main responsibility for planning their own and others' work (professionals) and those whose work is to a greater extent determined by others (associate professionals). Occupations with some autonomy but not overall planning or supervision within clerical, sales, and technical forms of work are classified as intermediate. Employees with supervisory responsibility for the work of intermediate workers are classified as higher supervisors. Employees with neither planning nor supervisory roles fall into three groups: those engaged in craft occupations (craft and related) and those engaged partly or wholly in routine work (semiroutine or routine workers). Employees with supervisory responsibility for craft and routine workers but who have no overall planning role are classified as lower supervisors.9,21 The classification does not distinguish between manual and non-manual work because “changes in the nature and structure of both industry and occupations has rendered this distinction both outmoded and misleading.”9 The concept of routine work has replaced that of skilled work. In the modern context, and most importantly in relation to women's occupations, it is far more relevant to know the extent to which an employee determines the content of their own work or has this laid down as a routine set by others, rather than the extent to which it concerns manual skills. The development of the classification system has involved extensive validation studies.21

Table 1.

Office for National Statistics' socioeconomic classification

| 13 category classes | Description | 7 category classes | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Employers in large firms (>25 staff) | 1 | Higher managerial and professional |

| L2 | Managers in large firms | ||

| L3 | Professionals | ||

| L4 | Associate professionals | 2 | Lower managerial and professionals |

| L5 | Managers in small firms | ||

| L6 | Higher supervisors (supervisors of intermediate workers) | ||

| L7.1 | Clerical and secretarial | 3 | Intermediate occupations |

| L7.2 | Intermediate public service occupations | ||

| L7.3 | Intermediate technical occupations | ||

| L8.1 and 8.2 | Employers in small firms | 4 | Small employers and own account occupations |

| L9.1 and 9.2 | Non-professional self employed occupations | ||

| L10 | Supervisors of craft and routine occupations | 5 | Lower supervisors, craft and related occupations |

| L11 | Craft and related occupations | ||

| L12 | Semiroutine occupations | 6 | Semiroutine occupations |

| L13 | Routine occupations | 7 | Routine occupations |

Cambridge scale

The Cambridge scale was originally derived from surveys by asking the occupations of the best friends and marriage partners of respondents, on the grounds that choices of marriage and friendship are the most important expression of perceived equality.10,22 Those pairs of occupations whose members seldom cited each other as friends were regarded as separated by a greater social distance, and those frequently cited, as less distant from each other. After ascertaining the comparative distances between all pairs of occupations, multidimensional scaling was used to extract the principal dimensions of the space so defined. This exercise yielded a single major dimension, supporting the concept of a single hierarchy of social interaction and social advantage12,23: the score on this factor is the Cambridge score. The Cambridge scale is derived from observed patterns of social interaction and makes no reference to employment relations or conditions as a source of social inequality.

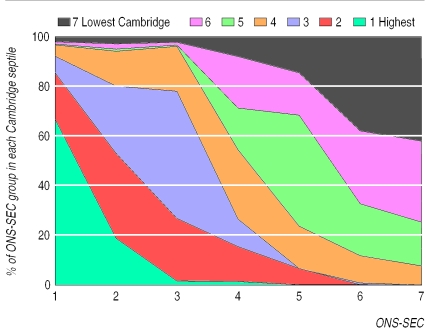

For our analysis we allocated men and women to the ONS socioeconomic classes by their own occupation. Because this approach considers general social advantage and its associated lifestyle as influenced by both men and women's own and their partner's occupation,24 each man and woman was allocated the higher of their own or their partner's Cambridge score if married or cohabiting. Single people living alone or as members of larger household groups were allocated a score on the basis of their own occupation. Figure 1 shows the relation between the ONS socioeconomic classes and the Cambridge score (ranked into septiles). It shows that there is a large proportion of the population whose position is assessed differently by the two classification systems.

Figure 1.

Relation between Office for National Statistics' socioeconomic classes and Cambridge score

Methods of analysis

We carried out separate analyses for men and women using Cox regression models controlling for age in five year bands. The risk of mortality in each social group is compared with that for all men or women, which is set to 1. We first carried out analyses with social class based on employment conditions (ONS socioeconomic classification) and general social advantage (Cambridge scale) predicting mortality separately. Because the two measures overlapped, we used multivariate models to assess whether there were separate independent effects of each one, and to compare the two. To compensate for the fact that the ONS socioeconomic classification is measured as seven categories whereas the Cambridge scale is a continuous measure, we ranked the Cambridge scores into seven groups ordered from greatest to least household advantage before being entered into the analyses.

Results

Table 2 shows the distribution of men and women among the categories of the ONS socioeconomic classes. Table 3 shows the age adjusted risk of mortality in men and women by their ONS socioeconomic classification and Cambridge scale compared with the overall risk in all men or all women. Employees with greater autonomy, security, and career structure (ONS socioeconomic classes 1 and 2) had a significantly lower risk of mortality than all men, as did self employed workers. Lower level supervisors and craft workers had higher mortality than all those in managerial and professional occupations or self employed workers but significantly lower mortality than semiroutine workers. Workers in routine occupations had significantly higher mortality than those in semiroutine occupations. With the exception of intermediate and self employed workers, mortality was statistically distinct for each group (confidence intervals did not overlap).

Table 2.

Distribution of men and women by Office for National Statistics' socioeconomic classes. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Socioeconomic class | Description | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Higher managerial and professional | 20 179 (13.9) | 7 973 (8.8) |

| 2 | Lower managerial and professional | 23 497 (16.2) | 12 119 (13.4) |

| 3 | Intermediate employees | 11 029 (7.6) | 27 469 (30.4) |

| 4 | Small employers or own account | 11 992 (8.3) | 2 836 (3.1) |

| 5 | Lower supervisors, craft and related | 26 242 (18.1) | 2 957 (3.3) |

| 6 | Employees in semiroutine occupations | 41 342 (28.6) | 21 129 (23.4) |

| 7 | Employees in routine occupations | 10 475 (7.2) | 15 844 (17.5) |

| Total | 144 756 (100) | 90 327 (100) |

Table 3.

Age adjusted relative risk of mortality for men and women by Office for National Statistics' socioeconomic classes and Cambridge septiles. Values are odds ratios (95% CIs) unless stated otherwise

| Men

|

Women

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| Office of National Statistics' socioeconomic class | |||||

| 1 Higher managerial and professional | 0.74 (0.70 to 0.77) | 0.83 (0.77 to 0.91) | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.84) | 0.99 (0.85 to 1.15) | |

| 2 Lower managerial and professional | 0.86 (0.82 to 0.90) | 0.90 (0.85 to 0.96) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.18) | 1.26 (1.14 to 1.40) | |

| 3 Intermediate employees | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.98) | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.93) | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.13) | |

| 4 Small employers or own account | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.99) | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 1.00 (0.86 to 1.15) | 1.08 (0.93 to 1.26) | |

| 5 Lower supervisors, craft and related | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.13) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) | 1.16 (1.02 to 1.33) | 0.92 (0.79 to 1.06) | |

| 6 Employees in semiroutine occupations | 1.18 (1.14 to 1.21) | 1.13 (1.08 to 1.19) | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.16) | 0.92 (0.84 to 0.99) | |

| 7 Employees in routine occupations | 1.38 (1.31 to 1.45) | 1.30 (1.21 to 1.38) | 1.14 (1.06 to 1.22) | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.94) | |

| Δχ2*, P value | 454, <0.0001 | 68, <0.0001 | 66, <0.0001 | 29, 0.0001 | |

| Cambridge scale | |||||

| 1 Greatest advantage | 0.72 (0.69 to 0.76) | 0.86 (0.79 to 0.94) | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.88) | 0.77 (0.69 to 0.87) | |

| 2 | 0.85 (0.81 to 0.89) | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) | 0.74 (0.67 to 0.82) | 0.71 (0.64 to 0.78) | |

| 3 | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.05) | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.12) | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.97) | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.90) | |

| 4 | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.08) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.05) | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.15) | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.08) | |

| 5 | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.14) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.05) | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.12) | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.17) | |

| 6 | 1.14 (1.10 to 1.19) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.10) | 1.24 (1.15 to 1.33) | 1.37 (1.25 to 1.51) | |

| 7 Least advantage | 1.25 (1.20 to 1.29 ) | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.14) | 1.42 (1.33 to 1.52) | 1.57 (1.44 to 1.72) | |

| Δχ2*, P value | 409, <0.0001 | 23, 0.0008 | 174, <0.0001 | 136, <0.0001 | |

df=6.

Mortality patterns in working women by the ONS socioeconomic classes are less clear. Higher managerial and professional women and intermediate workers (a large group in women) had significantly lower mortality than all other groups. Mortality risk in lower supervisors and women with semiroutine and routine occupations was significantly higher than the average for all working women, but these groups had similar risk levels to each other and to lower professional and self employed women (with average mortality). In contrast, mortality differences among women were substantial when expressed in terms of general social advantage as assessed by the Cambridge scale.

Table 3 shows the results of adjusting each measure of social position for the other. In men, social class based on employment relations (ONS classification) was found to have greater explanatory power than general social and material advantage (Cambridge scale) according to the difference in χ2 before and after adjustment, although both measures attenuate the effect of each other. In women, both measures made a significant independent contribution also, but the ONS classification had far less explanatory power than general social and material advantage both before and after adjustment. For women, the general social and material advantage of the household had a greater independent effect on mortality than social class based on employment relations. The gradient in women's mortality by household advantage (Cambridge scale) is steeper after adjusting for employment relations and conditions (ONS classification).

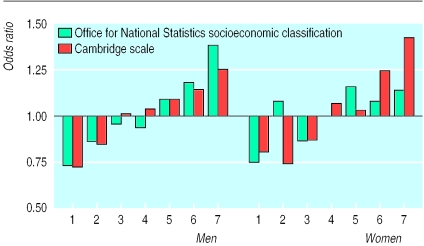

Figure 2 shows the differences between the ONS classification and the Cambridge scale in predicting mortality. In men, the mortality gradient between the “top” and “bottom” of the ONS classification is steeper than that with the Cambridge scale. The reverse situation is observed for women. The overall gradient between the ONS socioeconomic classes is both uneven and comparatively shallow whereas the mortality gradient with the Cambridge score shows a greater degree of inequality. The mortality risks in the top and bottom septiles of the Cambridge scale indicate that women with the least social and material advantage have roughly 1.75 times the risk of mortality of women with the greatest advantage, almost exactly the same ratio as that found in men.

Figure 2.

Age adjusted relative risk of mortality by Office for National Statistics' socioeconomic classes and Cambridge scale for men and women

Discussion

Even at a time of women's high participation in employment, the social basis for health inequalities still seems to differ according to sex. In men, the ONS socioeconomic classification, the government's new measure of social class, based on relations and conditions of employment produces a set of groups with a distinct risk of mortality that differ not just between higher managers and professionals and routine employees but throughout its full range. In women the effect of this variable was dwarfed by general social advantage. Both the ONS classification and the household Cambridge scale produced a range of relative mortality from around 25% below to 30% above the average for all men, whereas for women the two dimensions of social position did not capture the same variability in risk of mortality. In particular, women working in occupations with the least favourable conditions of employment had a 14% increased risk of mortality compared with the average, whereas women in households with least general social advantage had a 40% increased risk.

What is already known on this topic

Health inequality in women is studied far less often than in men, one reason being uncertainty about the best way to measure social inequality in women

Studies that use measures of social inequality based on their own occupation tend to show far less health inequality in women

Some studies have used measures of inequality based on concepts of deprivation or income, and these have tended to show comparatively greater extents of health inequality in women, but there are no studies using measures of inequality based on shared culture or common lifestyle

What this study adds

An analysis of data from 1% of the population of England and Wales, followed up from 1981-96, showed that in men the Office for National Statistics' new validated measure of social inequality based on employment relations and conditions produced clear differences in life expectancy between social groups

This measure, however, showed far less inequality in women

When a measure of social inequality based on general social advantage and lifestyle of the household was used, the extent of inequality in life expectancy was more or less identical in men and women

The difference in health inequality in women when using a measure of the general social advantage of the household rather than a measure based on occupational characteristics may have several explanations. Although women in their 20s and 30s will spend far more time in paid work than their mothers' generation, the great majority of deaths among women aged up to 59 take place at the higher end of this age range. Over their full life course these women will still have spent comparatively less time in the workplace than their male peers. So if routine work with little autonomy or opportunity for career advancement is simply regarded as a hazard, women have less exposure time. Secondly, the Cambridge scale has been shown to be more strongly related to health behaviours than are other measures of social position.18 This is not surprising given that it is derived from choices of friendship, which will reflect shared leisure pursuits and lifestyle. In women the importance of employment related factors relative to lifestyle outside the workplace would be expected to differ from that in men, once again due to differential exposure. Finally, the power of the Cambridge scale to predict mortality in women may also reflect the nature of women's “double day.” Working women (all in this analysis) in less advantaged households return home to a heavier burden of domestic labour, most of which falls on their shoulders, the disadvantage of their home situation amplifying any effects of work stresses and hazards. This is supported by the shape of the gradient relating general social advantage to mortality in women. At middle to higher levels of advantage, the gradient is less steep. In contrast with that of men, the risk of mortality in women increases sharply at the lower levels of advantage.

Conclusion

We have taken a new approach to understanding how health inequality differs between men and women. We have used separate measures of two different dimensions of social inequality that explicitly distinguish the effects of employment relations and conditions and general social advantage of the household. Our study shows that the relative importance of these dimensions is different in men and women and that the extent of health inequality in women compared with men is affected by the choice of measure.

Although social class based on employment relations was strongly related to risk of mortality in men, the relation of general social and material advantage in women was clearly dominant even in those who were employed at the time of the 1981 census. Additionally, the extent of inequality in women classified according to the level of general social advantage of their household is almost exactly that of men. Therefore any analysis that examines health inequality in women using only a measure of social position based on employment relations or conditions runs the risk of underestimating the size of the phenomenon. A better understanding of health inequality is possible when measures are used that are sensitive to the multidimensional nature of social inequality and the uneven effects of these dimensions on men and women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Office for National Statistics for allowing the use of its longitudinal study. The Office for National Statistics bears no responsibility for the analysis and interpretation expressed here.

Editorial by Vågerö

Footnotes

Funding: This work was funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council's social variations programme (grant No L128251001) and the Medical Research Council (grant No G8802774).

Competing interests: None declared.

Some occupations according to ONS classes and the Cambridge scale appear on the BMJ's website

References

- 1.Koskinen S, Martelin T. Why are socioeconomic mortality differences smaller among women than among men. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stronks K, van de Mheen H, van den Bos J, Mackenbach JP. Smaller socioeconomic inequalities in health among women: the role of employment status. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:559–568. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soni Raleigh K, Kiri V. Life expectancy in England: variations and trends by gender, health authority and level of deprivation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:649–658. doi: 10.1136/jech.51.6.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macintyre S, Hunt K. Socio-economic position, gender and health: how do they interact? J Health Psychol. 1997;2:315–334. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macran S, Clarke L, Sloggett A, Bethune A. Womens socioeconomic-status and self-assessed health—identifying some disadvantaged groups. Sociol Health Illness. 1994;16:182–208. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arber S. Comparing inequalities in women's and men's health: Britain in the 1990s. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:773–787. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moser KA, Pugh HS, Goldblatt PO. Inequalities in women's health—looking at mortality differentials using an alternative approach. BMJ. 1988;296:1221–1224. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6631.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahl E. Inequality in health and the class position of women: the Norwegian experience. Sociol Health Illness. 1991;13:491–505. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose D, O'Reilly K. Final report of the ESRC review of government social classifications. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council and Office for National Statistics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart A, Prandy K, Blackburn RM. Social stratification and occupations. London: Macmillan; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackburn RM, Marsh C. Education and social class: revisiting the 1944 education act with fixed marginals. Br J Sociol. 1991;42:507–536. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prandy K. The revised Cambridge scale of occupations. Sociology. 1990;24:629–655. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick R, Bartley M, Dodgeon B, Firth D, Lynch K. Social variation in health: relationship of mortality to the interim revised social classification. In: Rose D, O'Reilly K, editors. Constructing classes. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council and Office for National Statistics; 1997. pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandola T. Social inequality in coronary heart disease: a comparison of occupational classifications. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:525–533. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prandy K. Class, stratification and inequalities in health: a comparison of the registrar-general's and the Cambridge scale. Sociol Health Illness. 1999;21:466–484. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dollamore G. Examining adult and infant mortality rates using the NS-ONS. Health Stat Q. 1999;2:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arber S. Insights about the non-employed, class and health: evidence from the general household survey. In: Rose D, O'Reilly K, editors. Constructing classes. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council and Office for National Statistics; 1997. pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartley M, Sacker A, Firth D, Fitzpatrick R. Understanding social variation in cardiovascular risk factors in women and men: the advantage of theoretically based measures. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:831–845. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hattersley L, Creeser R. Longitudinal study 1971-1991: history, organisation and quality of data. London: HMSO; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leon D, Goldblatt P, Fox J. Social-class and mortality in occupational cohorts. Am J Ind Med. 1992;22:141–142. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700220115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose D, O'Reilly K. Constructing classes: towards a new social classification for the UK. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council and Office for National Statistics; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsh C, Blackburn RM. Class differences in access to higher education in Britain. In: Burrows R, Marsh C, editors. Consumption and class: divisions and change. London: Macmillan; 1992. pp. 184–211. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prandy K. Sociological research group working paper 18. Cambridge: Social and Political Sciences, Cambridge University; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall G, Roberts S, Burgoyne C, Swift A, Routh D. Class, gender and the asymmetry hypothesis. Eur Sociol Rev. 1995;11:1–15. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.