Abstract

Objective

Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) is a severe fibrosing disorder occurring in patients with renal insufficiency. The majority of patients with this disorder had documented exposure to magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents containing Gd. We examined the effects of Omniscan®, gadolinium diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA), and GdCl3 on the expression and production of cytokines and growth factors by normal human peripheral blood monocytes in vitro. We further examined whether conditioned media isolated from Gd-exposed peripheral blood monocytes could induce a profibrotic phenotype in dermal fibroblasts.

Methods

Normal human peripheral blood monocytes isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation and plastic adherence were incubated with various concentrations of Omniscan®, Gd-DTPA, or GdCl3. Gene expression of interleukins 4, 6 and 13, interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor α, transforming growth factor β, connective tissue growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor were assessed by real time PCR. Production and secretion of cytokines and growth factors by Gd-compound-exposed monocytes was quantitated by ELISA proteome multiplex arrays. The effects of conditioned media from the Gd-compound-exposed monocytes on the phenotype of normal human dermal fibroblasts were examined by real time PCR and Western blots.

Results

The three Gd-containing compounds stimulated expression and production of numerous cytokines and growth factors by normal human peripheral blood monocytes and conditioned media from these cells induced a profibrotic phenotype in normal human dermal fibroblasts.

Conclusion

The three Gd containing compounds studied induce potent cellular responses in normal human peripheral blood monocytes which may participate in the development of tissue fibrosis in NSF.

Keywords: Gadolinium, Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis/Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy, Collagen Gene Expression, Tissue Fibrosis, Monocytes/Macrophages, Fibroblasts

Background

Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF), previously known as Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy, is a serious fibrosing disease occurring in patients with renal insufficiency (1,2). Following the initial description, numerous additional cases have been identified across the globe (3-6). The typical clinical presentation includes subacute swelling of the distal parts of the extremities followed by progressive skin induration involving the legs, thighs, forearms, arms, and lower abdomen. Although NSF was initially considered to solely affect the skin, several studies have demonstrated involvement of other organs such as lungs, muscles and heart (5-8). Histopathological study of affected skin from NSF patients shows severe dermal and sub-dermal fibrosis, prominent mucin deposition, and increased fibroblast numbers (2). NSF affected tissues also exhibit accumulation of macrophages and activated fibroblasts, and markedly increased expression of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) compared to normal tissues (5).

Numerous risk factors have been suggested to be associated with the development of NSF besides renal insufficiency, however, following the initial description of the occurrence of five NSF cases in close temporal relationship with the administration of Gd-based contrast agents (GdBCA) for magnetic resonance imaging (9), it appears that the strongest and most consistent association is the administration of GdBCA (10-18). Free Gd3+ is acutely toxic, whereas, Gd3+ bound in a chelate complex is rendered chemically inert and less toxic (19,20). It has been proposed that transmetallation, a process in which circulating ions such as Zn2+ displace Gd3+ from the chelate complex may allow Gd3+ accumulation in the tissues (21-23). Owing to the markedly reduced rates of GdBCA clearance in patients with renal insufficiency the possibility of release of free Gd3+ from its chelate is markedly increased (24). Furthermore, several recent studies have demonstrated the presence of Gd in affected tissues from NSF patients (25-29), in some cases even for up to 2 years following the last administration of GdBCA (30). Ultrastructural studies employing electron spectroscopic imaging and energy loss spectroscopic analysis of affected NSF skin provided a striking demonstration of the perivascular deposition of Gd both surrounding cellular structures as well as adherent to collagen fibers of the extracellular matrix (31).

Six GdBCA have been approved for clinical use to enhance magnetic resonance images in the United States and three others have been approved for use in Europe. The vast majority of reported NSF cases (>85%) have been associated with administration of Omniscan®, although it accounts for only about 15% of GdBCA employed worldwide (11). Most of the remainder of cases have been associated with gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist®) and very few or no cases have been reported in association with other linear or macrocyclic GdBCA (15-17). It has been proposed that this disparity in the frequency of association between GdBCA and NSF may be explained by the differences in the rates of Gd dissociation from the various chelates (32-35).

We previously described that activated fibroblasts and macrophages are present in increased amounts in affected NSF skin and other affected visceral tissues (5). This observation prompted us to test the hypothesis that macrophages exposed to GdBCA become activated and produce growth factors and cytokines that, in turn, stimulate fibroblasts to cause the severe tissue fibrosis that is characteristic of NSF. To test this hypothesis we examined the effects of Omniscan®; gadolinium diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA), the Gd compound utilized in Magnevist®; and GdCl3 on the expression and production of a panel of profibrotic and proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors by normal human peripheral blood monocytes in vitro. Gd-DTPA and GdCl3 were included as other Gd-containing compounds which were commercially available. We further examined whether conditioned media isolated from peripheral blood monocytes exposed to GD-containing compounds could induce normal human dermal fibroblasts to display an increased expression of extracellular matrix molecules involved in the fibrotic process. The results demonstrate that the three Gd-containing compounds studied caused a potent stimulation of the expression and production of several profibrotic/proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors from normal human peripheral blood monocytes and that conditioned media from these cells induced a profibrotic phenotype in normal human dermal fibroblasts.

Materials and Methods

Gd compounds

Omniscan® and caldiamide (provided by GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK) were supplied as sterile, clear aqueous solutions. Omniscan® contained 287 mg/ml (500 mM) gadodiamide and 12 mg/ml caldiamide sodium in water, while the caldiamide solution contained 48 mg/ml (100 mM) caldiamide in water. Gd-DTPA and GdCl3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and were dissolved in sterile saline solution.

Monocyte Isolation

Normal human peripheral blood buffy coat preparations were obtained from the Thomas Jefferson University Hospital blood bank following Institutional Review Board approval. Buffy coat preparations from four different normal donors were examined. A second sample obtained from one of the same donors six months after the initial sample was also studied. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) and enriched for monocytes by adherence to plastic culture dishes for 2 h according to standard protocols (36). Isolation of total RNA from monocytes following various experimental conditions in vitro was performed according to the method described by Bender et al. (37).

Treatment of buffy coat-derived peripheral blood monocytes with Gd compounds

Equal numbers of buffy coat-derived peripheral blood mononuclear cells were plated in RPMI1640 media supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, L-glutamine and 10% FBS in 60 mm plastic culture dishes and enriched for monocytes by adherence for 2 h. Non-adherent cells were removed by repeated phosphate buffered saline (PBS) washes and adherent cells were incubated in fresh media containing either no additives or various concentrations of the study agents. LPS (1 μg/ml) was the positive control and sterile saline was the negative control. Four concentrations of either Gd-DTPA or Omniscan® (5, 10, 25 and 50 mM), four concentrations of caldiamide corresponding to the amounts present in the Omniscan® concentrations examined (250, 500, 1250 or 2500 μM), and three concentrations of GdCl3 (2.7, 27, and 270 μM) were used. Cells were collected at 1, 12 and 24 h following the addition of the agents. Cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 1,500 rpm and the supernatants representing conditioned media from Gd-exposed peripheral blood monocytes were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter, aliquoted, and stored at -20°C until used. The monocytes were processed for RNA extraction.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

SearchLight ELISA proteome array analyses (Pierce Biotechnology, Woburn, MA) were performed as described previously (38) to quantitate the levels of IL-4, IL-6, IL-13, IFN-γ, TGF-β, and VEGF in supernatants from peripheral blood monocytes that had been exposed to the Gd compounds for 24 h. Briefly, samples were diluted 1:2, 1:50, and 1:1,000 and then incubated for 1 h on the array plates which had been prespotted with capture antibodies specific for each protein. Plates were decanted and washed 3 times with PBS before addition of a mixture of biotinylated detection antibodies to each well. Following incubation with detection antibodies for 30 min, plates were washed 3 times and incubated for 30 min with streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase. Plates were again washed and SuperSignal Femto chemiluminescent substrate was added. The plates were immediately imaged using the SearchLight imaging system and data were analyzed using ArrayVision software.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Monocyte and fibroblast transcript levels were quantified using SYBR Green real time PCR, as previously described (39). Primers were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and validated for specificity. The primers employed were : β-actin, TTGCCGACAGGATGCAGAA (forward), GCCGATCCACACGGAGTACTT (reverse); IL-4, TGCTGCCTCCAAGAACACAA (forward), TGTAGAACTGCCGGAGCACA (reverse); IL-6, TGAGGAGACTTGCCTGGTGAAA (forward), TGGCATTTGTGGTTGGGTCA (reverse); IL-13, AGCTGGTCAACATCACCCAGAA (forward), AGCTGTCAGGTTGATGCTCCAT (reverse); IFN-γ, TTCAGATGTAGCGGATAATGGAAC (forward), TTCTGTCACTCTCCTCTTTCCA (reverse); TGF-β, CGAGCCTGAGGCCGACTA (forward), AGATTTCGTTGTGGGTTTCCA (reverse); VEGF, AGAAGGAGGAGGGCAGAATCAT (forward), TAATCTGCATGGTGATGTTGG (reverse); COL1A1, CCTCAAGGGCTCCAACGAG (forward), TCAATCACTGTCTTGCCCCA (reverse); α-SMA, TGTATGTGGCTATCCAGGCG (forward), AGAGTCCAGCACGATGCCAG (reverse). The differences in the number of mRNA copies in each PCR were corrected for human β-actin endogenous control transcript levels; levels in control experiments were set at 100 and all other values expressed as multiples of control values.

Fibroblast Cultures

Two normal human dermal fibroblast cell lines (passages 4-10) from the Scleroderma Center Tissue Bank, Thomas Jefferson University were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, antibiotics, 50 mM HEPES, and glutamine until confluent. For real-time PCR, cultured fibroblasts were harvested with trypsin-EDTA, washed with PBS, and then processed for RNA extraction using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as described previously (39).

Treatment of cultured fibroblasts with conditioned media from peripheral blood monocytes exposed to Gd compounds

Two normal human dermal fibroblast cell lines were cultured in complete medium in 6-well plates until confluence. Following preincubation for 24 h with 40 μg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to optimize their collagen production, fibroblasts were incubated for 24 h with conditioned media from Gd-exposed peripheral blood monocytes at a 1:2 dilution. Fibroblasts were then harvested and processed for RNA extraction. Type I collagen present in the culture media was assessed by Western blotting using a specific anti-human type I collagen polyclonal antibody (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA).

Statistical analysis

Real-time PCR values reflect the mean and standard deviation from five different experiments each performed in triplicate. The statistical significance of the real-time PCR data was assessed by Student’s two-tailed t test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Gd-compounds induce the expression of profibrotic/proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors in normal human peripheral blood monocytes

To examine the effects of Gd compounds on the expression levels of profibrotic/proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors, normal human peripheral blood monocytes were cultured with various concentrations of the Gd-containing compounds for 1, 12 or 24 h. The concentrations of Gd compounds employed in these studies were similar to those employed in previously published in vitro studies (40-42). Owing to the large variability in samples obtained at 1 h, these data are not shown in the results. The highest concentration of GdCl3 was toxic to the cells, as indicated by cytotoxicity assays and a marked reduction in housekeeping gene transcripts in quantitative PCR arrays (data not shown). Results obtained from 5 experiments with each of the Gd-containing agents examined, each in triplicate, utilizing peripheral blood monocytes isolated from buffy coat samples from 4 different normal donors were averaged. Two of the experimental samples were isolated from the same donor at a 6 month interval.

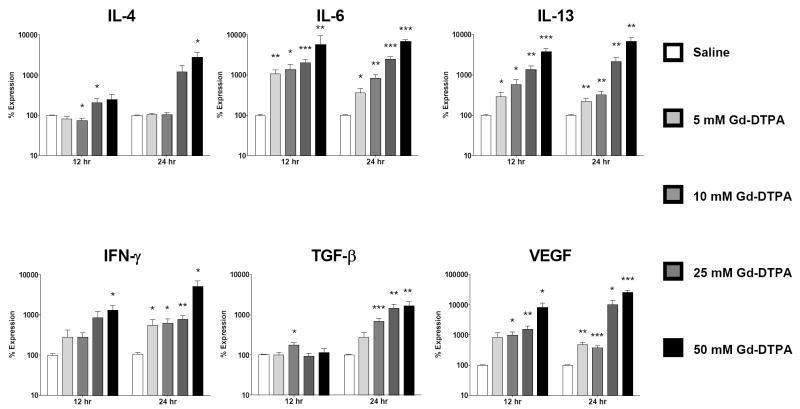

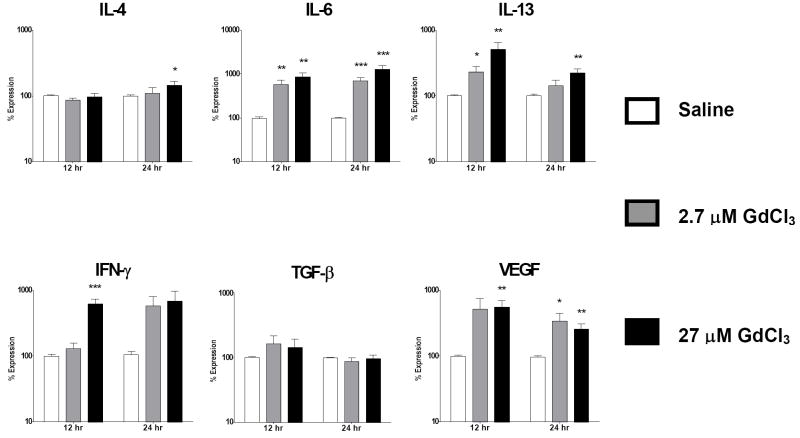

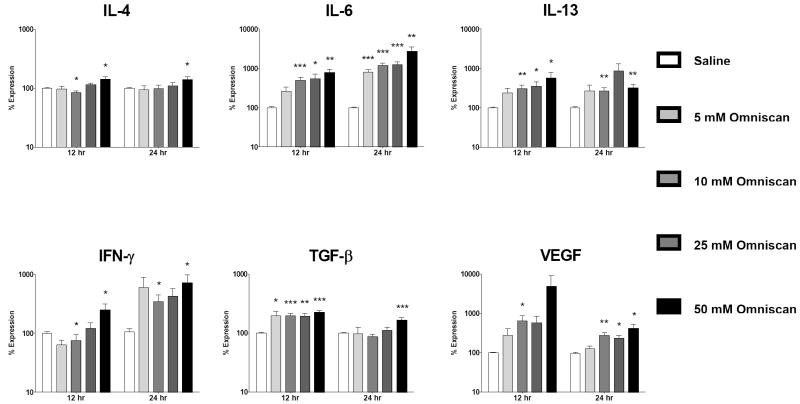

Analysis of expression levels of profibrotic/proinflammatory cytokines by real time PCR demonstrated that Gd compounds caused significant upregulation of expression of multiple cytokines and growth factors (Figs. 1-3). Gd-DTPA induced the strongest upregulation, followed by Omniscan®. GdCl3 produced the lowest level of change although the concentrations analyzed were the two lowest concentrations tested owing to high cytotoxicity of the higher concentrations.

Figure 1. Upregulated cytokine/growth factor expression is induced by Gd-DTPA in normal human peripheral blood monocytes.

Analysis of cytokine and growth factor expression levels by real time PCR at 12 and 24 h following exposure to Gd-DTPA. Values represent the mean (+/- standard deviation) expression levels of three replicates of five separate experiments with peripheral blood monocytes from four different normal individuals. Note that the data are presented in a semilogarithmic scale. C(t) values for cytokines were normalized with β-actin. The saline control levels were arbitrarily set at 100% expression at each time point. Values for other samples are expressed relative to the saline control. *: p<0.1; **: p < 0.01; ***: p<0.0001.

Figure 3. GdCl3 induces upregulation of cytokine/growth factor expression in normal human peripheral blood monocytes.

Analysis of cytokine and growth factor expression levels by real time PCR at 12 and 24 h following exposure to GdCl3. Values represent the mean (+/- standard deviation) expression levels of three replicates of five separate experiments with peripheral blood monocytes from four different normal individuals. Note that the data are presented in a semilogarithmic scale. C(t) values for cytokines were normalized with β-actin. The saline control levels were arbitrarily set at 100% expression at each time point. Values for other samples are expressed relative to the saline control. *: p<0.1; **: p < 0.01; ***: p<0.0001.

The growth factor VEGF displayed the greatest increase in expression of the cytokines/growth factors examined. Increasing concentrations of Gd-DTPA induced a 253 fold maximal increase in VEGF expression at 24 h (Fig. 1) compared to a 49 fold increase for Omniscan® at 12 h (Fig. 2) and a 6 fold increase for GdCl3 at 12 h (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Omniscan® activates expression of profibrotic/proinflammatory cytokines in normal human peripheral blood monocytes.

Analysis of cytokine and growth factor expression levels by real time PCR at 12 and 24 h following exposure to Omniscan®. Values represent the mean (+/- standard deviation) expression levels of three replicates of five separate experiments with peripheral blood monocytes from four different normal individuals. Note that the data are presented in a semilogarithmic scale. C(t) values for cytokines were normalized with β-actin. The saline control levels were arbitrarily set at 100% expression at each time point. Values for other samples are expressed relative to the saline control. *: p<0.1; **: p < 0.01; ***: p<0.0001.

The profibrotic cytokines IL-13, IL-4 and IL-6 also showed markedly increased expression in response to Gd compounds. For IL-13, Gd-DTPA produced a maximal 38 fold increase at 12 h which then rose to a 68 fold increase by 24 h (Fig. 1), Omniscan® induced a maximal 5 fold increase at 12 h and an 8 fold increase at 24 h (Fig. 2), while GdCl3 produced a 5 fold increase at 12 h (Fig. 3). For IL-4, Gd-DTPA caused a 28 fold increase at 24 h (Fig. 1), whereas, in contrast, its expression showed only a slight increase of 1.4 to 1.5 fold at 24 h in the presence of either Omniscan® (Fig. 2) or GdCl3 (Fig. 3). For IL-6, there was a potent stimulation with all three Gd-containing compounds (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). Expression of the potent profibrotic growth factor, TGF-β, was increased 2 fold at 12 h in the presence of Gd-DTPA (Fig. 1) compared to 3 fold at 12 h for Omniscan® (Fig. 2) and 1.6 fold for GdCl3 (Fig. 3).

Gd-DTPA increased expression of IFN-γ by 50 fold at 24 h (Fig. 1) compared to 7 fold for Omniscan® at 12 h (Fig. 2) and 5 fold for GdCl3 at 12 h (Fig. 3). In contrast, the expression levels of two other cytokines examined, CTGF and TNF-α, were not affected by exposure to any of the Gd-containing compounds, indicating that the upregulation observed for the other cytokines and growth factors was not a non-specific effect but reflected a real monocyte response. The kinetics of stimulation of expression of the various cytokines and growth factors following exposure to Gd-containing compounds varied. The highest transcript levels for all cytokines were observed at 24 h in cells exposed to Gd-DTPA although a substantial response was seen as early as 12 h for all cytokines/growth factors except TGF-β (Figs. 1-3). For Omniscan®, the highest expression levels for IL-4, TGF-β, and VEGF were observed at 12 h, whereas IL-6, IL-13 and IFN-γ demonstrated highest expression at 24 h (Figs. 1-3). IL-13, TGF-β, IFN-γ and VEGF showed highest expression at 12 h in cells exposed to GdCl3 and IL-4 and IL-6 showed highest expression at 24 h (Figs. 1-3). The magnitude of the response and the kinetics observed varied considerably between the samples obtained from the 4 individual donors, however, two experiments conducted on peripheral blood monocytes isolated from the same donor at a 6 month interval showed remarkably similar magnitude and timing of response to the three agents examined (data not shown).

Caldiamide induces the expression of some profibrotic/proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors in normal human peripheral blood monocytes

Caldiamide, the chelate component of commercially prepared Omniscan®, was also tested to evaluate its effects on cytokine/growth factor expression. Four concentrations (250, 500, 1250, and 2500 μM) which were equivalent to the amounts of caldiamide present in the 5, 10, 25 and 50 mM concentrations of Omniscan® tested were evaluated. Following 24 h incubation with Caldiamide only modest increases in cytokine/growth factor transcript levels were observed (data not shown). In comparison with the increases observed for Omniscan® (Figure 2), Caldiamide had no effect on expression levels of IL-4, whereas it increased IL-6 expression 2 fold compared to 27 fold for Omniscan®, IFN-γ expression 2 fold compared with 7 fold for Omniscan®, and IL-13 expression 4 fold compared to 8 fold for Omniscan®. TGF-β transcript levels were essentially unchanged compared to Omniscan® and VEGF expression was significantly reduced compared with a 49 fold increase with Omniscan®.

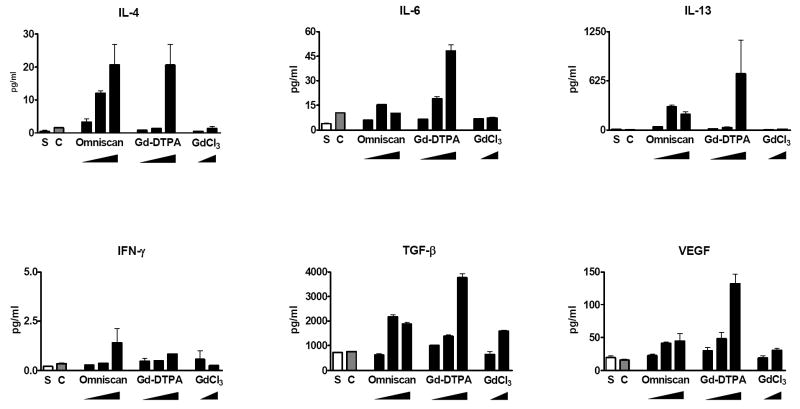

Gd-containing compounds stimulate peripheral blood monocyte production and secretion of profibrotic/proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors

To confirm that the increased expression observed at the transcript level by real time PCR was reflected at the protein level, SearchLight proteome multiplex arrays were utilized to quantitate by ELISA the amounts of relevant profibrotic and proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors produced by peripheral blood monocytes following exposure to GdBCA and GdCl3. The results showed that 24 h exposure to the three Gd-containing compounds resulted in increased production and secretion of numerous cytokines and growth factors with their significant accumulation in the culture media as shown in Fig. 4. The results, expressed in pg/ml, were normalized for the value of β-actin transcripts obtained in the real-time PCR experiments in order to correct for possible variance in the number of adherent cells analyzed. All of the cytokines/growth factors that exhibited upregulated mRNA expression following exposure to Gd-DTPA, Omniscan®, and GdCl3 also demonstrated an increase in the total amount of the corresponding secreted cytokine/growth factor. Interestingly, exposure of monocytes to caldiamide did not result in a detectable increase in the production of any of the cytokines/growth factors analyzed except for some increase in IL-4 and IL-6 production (Fig. 4). Exposure to Gd-DTPA induced stronger production of most of the cytokines and growth factors, followed by Omniscan® and then GdCl3.

Figure 4. Amount of secreted cytokines and growth factors in cell culture supernatants from Gd-compound-exposed normal human peripheral blood monocytes.

Quantitative measurement of cytokines and growth factors present in the culture media of Gd-compound-exposed cells was performed by multiplex proteome array analyses as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were incubated with either saline (S), caldiamide (C; 2500 μM), Omniscan® (5, 25, or 50 μM), Gd-DTPA (5, 25, or 50 μM), or GdCl3 (2.7 or 27 μM). Values are expressed in pg/ml and represent the mean value of values obtained from duplicate results at 3 dilutions: 1:2, 1:50 and 1:1000.

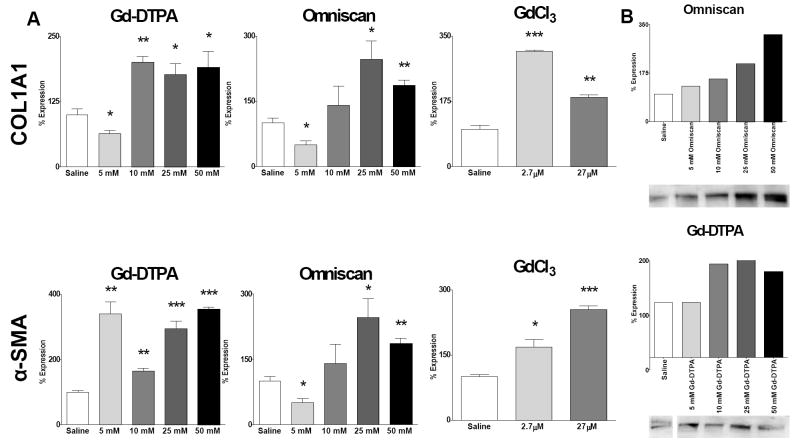

Conditioned media from Gd-stimulated peripheral blood monocytes induce a profibrotic phenotype in normal human dermal fibroblasts

To provide a functional correlation between the data obtained with the quantitative assessments of cytokine and growth factor levels and a potential fibrogenic effect, normal human dermal fibroblasts were incubated with conditioned media isolated from Gd-exposed human peripheral blood monocytes. The results (Fig. 5A) showed that fibroblasts cultured with conditioned media from peripheral blood monocytes exposed to media from cells cultured with Omniscan® displayed a nearly threefold maximum increase in type I collagen gene expression. Gd-DTPA also increased the levels of COL1A1 transcripts twofold with media from cells cultured with either 25 mM or 50 mM. The media from cells cultured with 2.7 μM GdCl3 concentration induced a threefold increase in COL1A1 transcripts. Transcript levels for α-SMA, a marker of myofibroblast differentiation, were increased maximally nearly threefold by media from cells cultured with 10 mM Omniscan® (Fig. 5A). Media from cells exposed to Gd-DTPA produced even more pronounced stimulation inducing a greater than threefold increase, whereas, the media from cells cultured with 27 μM concentration of GdCl3 induced a greater than twofold increase in α-SMA transcript levels. Western blot analysis of media from the fibroblast cultures showed increased type I procollagen production in fibroblasts exposed to conditioned media isolated from either Omniscan® or Gd-DTPA-exposed normal human peripheral blood monocytes (Fig. 5B). Quantification by Image J software revealed that Omniscan® upregulated type I procollagen levels with a dose response pattern, with media from cells cultured with 50 mM Omniscan® inducing a 313% increase over the saline control, whereas media from cells cultured with 25 mM Gd-DTPA induced a maximal increase in type I procollagen production of 173% (Fig. 5B). Western blot of supernatants from fibroblasts exposed to GdCl3 showed only a minimal effect on collagen production (data not shown).

Figure 5. Conditioned media from Gd compound-exposed peripheral blood monocytes induce expression of COL1A1 and α-SMA transcripts and increased production of type I procollagen by normal human dermal fibroblasts.

Normal dermal human fibroblasts were incubated for 24 h in standard tissue culture media containing a 1:2 dilution of culture media isolated from peripheral blood monocytes exposed to Gd-containing compounds. (A) Expression levels of COL1A1 and α-SMA transcripts determined by real time PCR. The results shown are representative of two separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. (B) Production of type I collagen assessed by Western blots and quantified employing Image J software. The saline control levels were arbitrarily set at 100%. Values for the samples are expressed as the percent increase over the saline control value. *: p<0.1; **: p < 0.01; ***: p<0.0001.

Discussion

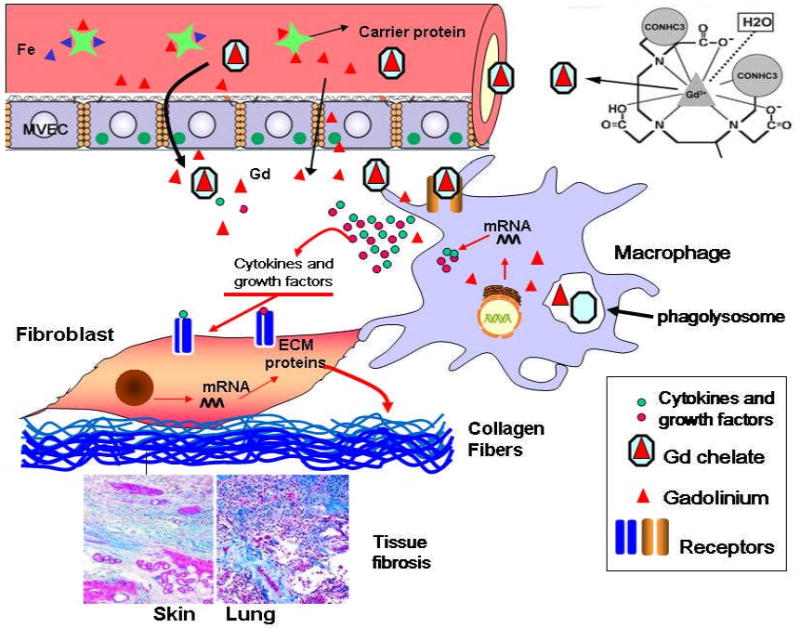

Numerous studies have identified exposure to GdBCA as a triggering event in the development of NSF (9-18). However, the mechanisms by which these compounds may result in tissue fibrosis or may exert a profibrotic effect on the cells affected in this condition are just beginning to become clarified. Activation of tissue macrophages has been demonstrated to be an early event in the development of several fibrotic conditions (43-45), and previous observations from our group of the presence of abundant activated macrophages in affected NSF tissues suggested that these cells could play a role in NSF pathogenesis. Here, we present data supporting the hypothesis that macrophages exposed to GdBCA are induced to produce and secrete proinflammatory/profibrotic cytokines which, in turn, cause the activation of dermal fibroblasts resulting in the increased expression of genes encoding interstitial collagens and other extracellular matrix molecules. This proposed sequence of events is diagrammatically depicted in Fig. 6. The figure shows that Gd-containing compounds escape into the extravascular space where they interact with tissue macrophages and stimulate the expression of genes encoding a variety of profibrotic/proinflammatory cytokines and the production and secretion of their corresponding products. These secreted macrophage products act on resident tissue fibroblasts, inducing their differentiation into α-SMA expressing myofibroblasts and stimulating them to increase their production and secretion of molecules involved in the fibrotic process such as collagens. The exact mechanisms involved in the escape of Gd-containing compounds into the extravascular space are not entirely known, however, it is likely that higher concentrations and increased retention in the circulation owing to renal insufficiency, alterations in endothelial permeability resulting from inflammatory or thrombotic events, presence of tissue edema, or other factors may all contribute.

Figure 6. Schematic representation of proposed mechanisms of the profibrotic effects of Gd compounds.

Chemical structure of gadodiamide is from (31).

Our results show that Gd compounds can induce expression and secretion by normal human peripheral blood monocytes of several cytokines and growth factors generally accepted to play important roles in the initiation and/or progression of the fibrotic process. Further, we demonstrate that cell culture supernatants isolated from Omniscan® and Gd-DTPA exposed peripheral blood monocytes stimulate the production and secretion of type I procollagen and the expression of α-SMA. The observed changes in the expression and secretion of a number of well characterized cytokines and growth factors involved in inflammation and fibrosis was consistent in five separate experiments each performed in triplicate utilizing buffy coats from four different normal individuals. However, it should be emphasized that the population of cells used in this study although substantially enriched for monocytes is heterogeneous and likely contains a small proportion of contaminating lymphocytes. The variability in the cellular response of monocytes to the Gd compounds likely reflects genetic heterogeneity and/or variability in the sensitivity of peripheral blood monocytes derived from different individuals to the activating stimulus. The heterogeneity in response and the variable sensitivity of peripheral blood monocytes to stimulation may be one factor which could explain the relatively infrequent occurrence of NSF among the large population of patients with renal insufficiency exposed to GdBCA. Another possibility to be considered is that cells derived from patients with renal insufficiency who develop NSF may have a more pronounced response to Gd compounds than those derived from normal patients, although our study does not directly address this possibility. We believe, however, that our results are compelling since they demonstrate that even cells obtained from normal individuals are capable of mounting a very strong response to Gd-containing compounds. Given the frequency of inflammatory events in patients with acute and chronic renal failure, the numbers of tissue bound or circulating monocytes present in an activated state would be considerably higher than those present in normal individuals and it is plausible that cells within a pro-inflammatory microenvironment may potentially be more sensitive to the stimulating and activating effects of Gd compounds than monocytes not previously exposed to such inflammatory mediation.

We acknowledge that the concentrations of GdBCA employed here are substantially higher than those found in individuals with normal renal function following their administration for imaging studies, although the actual concentrations of these compounds in tissues of patients with renal insufficiency are not known and are very likely to be much greater than those calculated from the pharmacokinetic studies (24,46). The concentrations of Gd and GdBCA utilized in these experiments were based on published in vitro studies (40-42) and were chosen to encompass some of the higher and lower reported concentrations. Two recent studies examining directly the potential profibrotic effects of GdBCA employed similar concentrations of GdBCA to the ones we employed here (41,47). The first study examined the effects of in vivo administration of repeated doses of Omniscan® to rats. This study found that a cumulative dose of 2.5 mM/kg Omniscan® induced fibrosis-like changes in rat dermis (47). This regime would be expected to yield extracellular Omniscan® concentrations in the 2-7 mM range. A second study examined the effects of Omniscan® on proliferation and hyaluronan production by dermal fibroblasts in culture (41). The results showed that 1 mM Omniscan® induced an approximately twofold increase in fibroblast proliferation over 7 days, with doses as high as 20 mM causing a proliferative effect on dermal fibroblasts. Hyaluronan production was also stimulated with the greatest effect observed at a 10 mM concentration (41).

The results from ELISA assays of culture supernatants from monocytes exposed to Gd compounds demonstrated increased production of several cytokines and growth factors which may participate in the fibrotic process, as well as in the neovascularization and other vascular abnormalities often present in the most severe forms of the disease (5,6). These results are in agreement with the remarkable increase in numerous inflammatory cytokines recently described in rats receiving repeated intravenous injection of gadodiamide (50).

Although the gene expression studies showed a marked increase in IFN-γ transcripts following exposure of the mononuclear cells to the Gd compounds, the actual amounts of the cytokine measured in the cell culture supernatants were rather modest. Thus, despite the well recognized antifibrotic effects of IFN-γ and of its ability to counteract the profibrotic effects of TGF-β (48,49), the overall response of monocytes to Gd exposure was skewed toward a potent profibrotic effect.

Taken together, the results described here demonstrate that Gd-containing compounds are capable of inducing remarkable phenotypic changes in normal human peripheral blood monocytes including the increased expression of genes encoding several well-characterized profibrotic and proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors. Furthermore, the conditioned medium from these cells induced upregulation of α-SMA expression and type I collagen production in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Thus, the present study provides strong evidence and plausible pathophysiological mechanisms for a pivotal role of Gd-containing compounds in the development of NSF. Further study and characterization of the cellular effects of these compounds and of the mechanisms of these effects may provide valuable information regarding the early events in the pathogenesis of NSF and other fibrosing diseases such as systemic sclerosis.

Acknowledgments

Supported by an Investigator Initiated Grant (IIG) from GE Healthcare to S.A.J. P.J.W. was supported by NIAMS Training Grant T-32 AR007583-15.

The expert assistance of Susan V. Castro, Ph.D., in the preparation of this manuscript is gratefully acknowledged.

Bibliography

- 1.Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, Su LD, Supta S, LeBoit PE. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous disease in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356:1000–1001. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, Robin HS, LeBoit PE. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:383–393. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackay-Wiggan JM, Cohen DJ, Hardy MA, Knobler EH, Grossman ME. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (scleromyxedema-like illness of renal disease) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:55–60. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swartz RD, Crofford LJ, Phan SH, Ike RW, Su LD. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: a novel cutaneous fibrosing disorder in patients with renal failure. Am J Med. 2003;114:563–572. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jimenez SA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, Derk C, Latinis K, Sawaya H, Haddad R, Shanahan JC. Dialysis-associated systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy): study of inflammatory cells and transforming growth factor beta1 expression in affected skin. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2660–2666. doi: 10.1002/art.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendoza FA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, Latinis K, Piera-Velazquez S, Jimenez SA. Description of 12 cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:238–449. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ting WW, Stone MS, Madison KC, Kurtz K. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with systemic involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:903–906. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.7.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine JM, Taylor RA, Elman LB, Bird SJ, Lavi E, Stolzenberg ED, McGarvey ML, Asbury AK, Jimenez SA. Involvement of skeletal muscle in dialysis-associated systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy) Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:569–577. doi: 10.1002/mus.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grobner T. Gadolinium—a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1745. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, Dupont A, Damholt MB, Heaf JG, Thomsen HS. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected etiological role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2359–2362. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomsen HS. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a serious late adverse reaction to gadodiamide. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:2619–2621. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0495-8. Epub 2006 Oct 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deo A, Fogel M, Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a population study examining the relationship of disease development to gadolinium exposure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:264–267. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03921106. Epub 2007 Feb 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, Heaf JG, Thomsen HS. Case-control study of gadodiamide-related nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:3174–3182. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm261. Epub 2007 May 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowper SE. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis: A Review and Exploration of the Role of Gadolinium. Adv Derm. 2007;23:131–154. doi: 10.1016/j.yadr.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penfield JG, Reilly RF. What nephrologists need to know about gadolinium. Nat Clin Prac. 2007;3:654–668. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broome DR. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis associated with gadolinium based contrast agents: A summary of the medical literature reporting. Eur J Radiol. 2008;66:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Todd DJ, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Kay J. Cutaneous changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: predictor of early mortality and association with gadolinium exposure. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3433–3341. doi: 10.1002/art.22925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurtkoti J, Snow T, Hiremagalur B. Gadolinium and Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: Association or causation. Nephrology. 2008;13:235–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oskendal A, Hals P. Biodistribution and toxicity of MR imaging contrast media. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1993;3:157–165. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880030128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shellock FG, Kanal E. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10:477–484. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199909)10:3<477::aid-jmri33>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cacheris WP, Quay SC, Rocklage SM. The relationship between thermodynamics and the toxicity of gadolinium complexes. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:467–81. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puttagunta NR, Gibby WA, Smith GT. Human in vivo comparative study of zinc and copper transmetallation after administration of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Invest Radiol. 1996;31:739–42. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199612000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Idée JM, Port M, Raynal I, Schaefer M, Le Greneur S, Corot C. Clinical and biological consequences of transmetallation induced by contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging: a review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2006;20:563–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2006.00447.x. Erratum in: Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007. 21:335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joffe P, Thomsen HS, Meusel M. Pharmacokinetics of gadodiamide injection in patients with severe renal insufficiency and patients undergoing hemodialysis or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Acad Radiol. 1998;5:491–502. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(98)80191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.High WA, Ayers J, Chandler J, Zito G, Cowper SE. Gadolinium is detectable within the tissue of patients with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thakral C, Alhariri J, Abraham JL. Long-term retention of gadolinium in tissues from nephrogenic systemic fibrosis patient after multiple gadolinium-enhanced MRI scans: case report and implications. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2007;2:199–205. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyd AS, Zic JA, Abraham JL. Gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.048. Epub 2006 Nov 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khurana A, Greene JF, Jr, High WA. Quantification of gadolinium in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: re-examination of a reported cohort with analysis of clinical factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kay J, Bazari H, Avery LL, Korishi AF. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 6-2008. A 46-year-old woman with renal failure and stiffness of the joints and skin. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:827–837. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc0708697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abraham JL, Thakral C, Skov L, Rossen K, Marckmann P. Dermal inorganic gadolinium concentrations: evidence for in vivo transmetallation and long-term persistence in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:273–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroeder JA, Weingart C, Coras B, Hausser I, Reinhold S, Mack M, Seybold V, Vogt T, Banas B, Hofstaedter F, Krämer BK. Ultrastructural evidence of dermal gadolinium deposits in a patient with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:968–75. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morcos SK. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis following the administration of extracellular gadolinium based contrast agents: is the stability of the contrast agent molecule an important factor in the pathogenesis of this condition? Br J Radiol. 2007;80:73–76. doi: 10.1259/bjr/17111243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuo PH. Gadolinium-containing MRI contrast agents: important variations on a theme for NSF. J Am Coll Radiol. 2008;5:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morcos SK. Extracellular gadolinium contrast agents: Differences in stability. Eur J Radiol. 2008;66:175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Port M, Idée JM, Medina C, Robic C, Sabatou M, Corot C. Efficiency, thermodynamic and kinetic stability of marketed gadolinium chelates and their possible clinical consequences: a critical review. Biometals. 2008;21:469–490. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies MQ, Gordon S. Isolation and culture of human macrophages. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;290:105–116. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-838-2:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bender AT, Ostenson CL, Giordano D, Beavo JA. Differentiation of human monocytes in vitro with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor produces distinct changes in cGMP phosphodiesterase expression. Cell Signal. 2004;16:365–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moody MD, Van Arsdell SW, Murphy SW, Murphy KP, Orencole SF, Burns C. Array-based ELISAs for high-throughput analysis of human cytokines. Biotechniques. 2007;31:186–190. 192–194. doi: 10.2144/01311dd03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Del Galdo F, Jimenez SA. T Cells Expressing Allograft Inflammatory Factor 1 Display Increased Chemotaxis and Induce a Profibrotic Phenotype in Normal Fibroblasts In Vitro. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3478–3488. doi: 10.1002/art.22877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkins GL, Derfoul A, Ast A, Hall DJ. An inhibitor of the stretch-activated cation receptor exerts a potent effect on chondrocyte phenotype. Differentiation. 2005;73:199–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edward M, Quinn J, Mukherjee S, Jensen MB, Jardine A, Mark P, Burden A. Gadodiamide contrast agent ‘activates’ fibroblasts: a possible cause of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Pathol. 2008;214:584–93. doi: 10.1002/path.2311. Erratum in J. Pathol 2008 214:593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heinrich MC, Kuhlmann MK, Kohlbacher S, Scheer M, Grgic A, Heckmann MB, Uder M. Cytotoxicity of iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents in renal tubular cells at angiographic concentrations. Radiology. 2007;242:425–434. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422060245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pernis B. Silica and the immune system. Acta Biomed. 2005;76(Suppl 2):38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kräling BM, Maul GG, Jimenez SA. Mononuclear cellular infiltrates in clinically involved skin from patients with systemic sclerosis of recent onset predominantly consist of monocytes/macrophages. Pathobiology. 1995;63:48–56. doi: 10.1159/000163933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Goor H, Ding G, Kees-Folts D, Grond J, Schreiner GF, Diamond JR. Macrophages and renal disease. Lab Invest. 1994;71:456–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.VanWagoner M, Worah D. Gadodiamide injection: first human experience with the nonionic magnetic resonance imaging enhancement agent. Invest Radiol. 1993;28:S44–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sieber MA, Pietsch H, Walter J, Haider W, Frenzel T, Weinmann HJ. A preclinical study to investigate the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a possible role for gadolinium-based contrast media. Invest Radiol. 2008;43:65–75. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31815e6277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jimenez SA, Freundlich B, Rosenbloom J. Selective inhibition of human diploid fibroblast collagen synthesis by interferons. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:1112–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI111480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varga J, Olsen A, Herhal J, Constantine G, Rosenbloom J, Jimenez SA. Interferon-gamma reverses the stimulation of collagen but not fibronectin gene expression by transforming growth factor-beta in normal human fibroblasts. Eur J Clin Invest. 1990;20:487–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1990.tb01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steger-Hartman T, Raschke M, Riefke B, Pietsch H, Sieber MA, Walter J. The involvement of pro-inflammatory cytokines in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis – A mechanistic hypothesis based on preclinical results from a rat model treated with gadodiamide. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.11.004. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]