Abstract

Chemically deposited silver particles are widely used for surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) and more recently for surface-enhanced fluorescence (SEF), also known as metal-enhanced fluorescence (MEF). We now show that metallic silver deposited by laser illumination results in an ~7-fold increased intensity of locally bound indocyanine green. The increased intensity is accompanied by a decreased lifetime and increased photostability. These results demonstrate the possibility of photolithographic preparation of surfaces for enhanced fluorescence in microfluidics, medical diagnostics, and other applications.

Index Headings: Metal-enhanced fluorescence, Radiative decay engineering, Radiative decay rate, Laser-deposited silver

INTRODUCTION

Fluorescence has become the dominant detection technology in medical diagnostics and biotechnology. While fluorescence provides high sensitivity, there exists the need for reduced detection limits and/or small copy-number detection. Detectability is usually limited by auto-fluorescence of the samples and/or the photostability of the fluorophores. In an effort to obtain increased sensitivity, we have recently investigated the use of metallic surfaces or particles to favorably modify the spectral properties of fluorophores.1–4 We demonstrated that proximity of fluorophores to metallic silver particles results in increased intensities, quantum yields, photostability, and decreased lifetimes. These results are consistent with increased radiative decay rates of the fluorophores, Γ, induced by an interaction with these metallic surfaces. These effects have been predicted theoretically5–7 and are related to surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), except that the effects on fluorescence are thought to be due to through-space interactions, which do not require molecular contact between the fluorophores and the metal.

For use in medical and biotechnology applications, such as diagnostic or microfluidic devices, it would be useful to obtain metal-enhanced fluorescence (MEF) at desired locations in the measurement device. While a variety of methods could be used, we reasoned that the light-directed deposition of silver would be widely applicable. In recent years, a number of laboratories have reported light-induced reduction of silver salts to metallic silver.8–11 Typically, a solution of silver nitrate is used that contains a mild potential reducing agent such as a surfactant10 or dimethylformamide.11 Exposure of such solutions to ambient or laser light typically results in the formation of silver colloids in suspension or on the glass surfaces. These results suggested the use of light-induced silver deposition for locally enhanced fluorescence.

In the present report we examined the long-wavelength dye indocyanine green (ICG), which is widely used in a variety of in vivo medical applications.12–16 ICG displays a low quantum yield in solution, ~0.016,17 and a somewhat higher quantum yield when bound to serum albumin.18–20 Albumin adsorbs to form a monolayer21,22 and ICG spontaneously binds to albumin. ICG is chemically and photochemically unstable, and thus provided us with an ideal opportunity to test photo-deposited silver for both metal-enhanced emission and increased photochemical stability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Indocyanine green (Fig. 1) and human serum albumin (HSA) were obtained from Sigma and used without further puri cation. Emission spectra of ICG were measured using an SLM 8000 spectrofluorometer with an excitation wavelength of 760 nm from a Spectra Physics Tsunami Ti: Sapphire laser in the continuous-wave (CW, non-pulsed) mode, vertically polarized, 760 nm incident on the sample at 45° from the normal. Emission spectra were recorded at the magic angle. Intensity decays were also measured at the magic angle, 54.7°, by time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC), using an SPC630 PC card (Becker and Hickl Gmbh), in reverse start-stop mode. The 760 nm excitation was obtained from a mode-locked Argon-ion pump, cavity-dumped Pyridine 2 dye laser with 3.77 MHz repetition rate. The instrumental response function was <40 ps full width at half-maximum (FWHM).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of indocyanine green (ICG).

The intensity decays were analyzed using nonlinear least-squares impulse reconvolution in terms of the multi-exponential model:

| (1) |

where αi are the pre-exponential factors and τi are the decay times, Σαi = 1.0. The fractional contribution of each component to the steady-state intensity is given by:

| (2) |

The mean lifetime of the excited state is given by:

| (3) |

The amplitude-weighted lifetime is given by:

| (4) |

For the laser deposition of silver particles, clean glass substrates were silanized with 3-aminopropyl trimethoxysilane (APS) or 3-m ercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane (MCTMS). Glass microscope slides (Aldrich Chemical Co.) were rst cleansed in a 10:1 (v/v) mixture of H 2SO 4 (98%) and H2O 2 (30%). The slides were subsequently treated with an appropriate % volume/volume (v/v) silanization agent for one hour to form the adhesion layer on the glass substrate. Water or ethanol was used to form the silanization solution for APS and MCTMS, respectively. This treatment coats the glass surface with either amine groups, in the case of APS, or thiol groups, for MCTMS, which are well known to bind to silver colloids from solution. After washing in distilled water to remove excess agents, the slides were then ready for the laser deposition of silver.

The silver-colloid-forming solution was prepared by adding 4 mL of 1% trisodium citrate solution to a warmed 200 mL 10−3 M AgNO 3 solution. This warmed solution already contains some silver colloids as seen from a surface plasmon absorption optical density near 0.1. A 180 μL aliquot of this solution was syringed between the glass microscope slide and the plastic cover slip (CoverWell PCI 0.5), which created a micro-sample chamber 0.5 mm thick (Fig. 2). For all experiments a constant volume of 180 μL was used. Irradiation of the sample chamber was undertaken using a HeCd laser, Li-conix Model 4240PS, with a power of ~8 mW, which was collimated and defocused using a 10× microscope objective, numerical aperture (NA) 0.40, to provide illumination over a 0.5 mm diameter spot. Following silver deposition, the slides were rinsed and incubated for 24 h in a 30 μM ICG, 60 μM HSA buffered solution. The HSA–ICG-coated slides were then sandwiched with another uncoated glass microscope slide, which formed a microcuvette, with an approximate 1 μm path length. Buffer in the small cavity prevented the HSA–ICG above the silver and on the glass (unsilvered areas) from drying out during measurements.

Fig. 2.

Experimental setup for laser deposition of silver on APS coated glass microscope slides.

RESULTS

Illumination of the APS and MCTMS treated slides at 442 nm resulted in the deposition of metallic silver in the illuminated region. Laser-deposited silver could be seen visually within minutes; however, deposited silver could not be observed with room light exposure for a similar period of time. However, over much longer time periods, e.g., 4 days, silver was evident on the glass slides, suggesting that even ambient room light can produce silver colloids, which can adhere to the surfaces over much longer time periods. To some extent, this observation also manifests itself in the fact that bottles of long-standing silver nitrate on a laboratory shelf are coated with metallic silver over time.

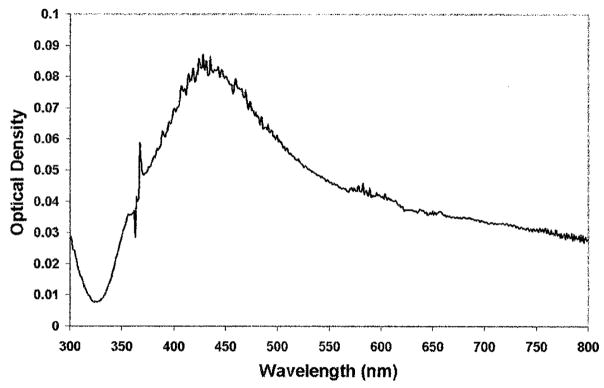

The laser-deposited silver displayed a surface plasmon absorption (Fig. 3) typical of sub-wavelength-size silver particles. Silver was deposited on both the microscope slide and the cover slip, but signi cantly more silver was visible on the treated slides than on the untreated cover slip. The optical density of the deposited silver increased approximately linearly with illumination time (data not shown), increasing much more rapidly with MCTMS treated slides (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Absorption spectrum of a 0.5% v/v APS coated glass slide after 5 min illumination with a 442 nm HeCd laser.

Indocyanine green in a tricarbocyanine dye displays long-wavelength absorption and emission, 795 and 810 nm, respectively. ICG binds spontaneously to human serum albumin, which in turn adsorbs to silvered glass surfaces.21,22 We recently reported increased intensities of ICG–HSA when bound to silver island lms (SIFs).23 These lms are formed by chemical reduction of silver and consist of a heterogeneous population of silver particles bound to glass.24 SIFs are frequently used for SERS. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of SERS or surface-enhanced fluorescence (SEF) using light-deposited silver.

We examined the emission spectrum of ICG–HSA when bound to illuminated or non-illuminated regions of the APS and MCTMS treated slides. For APS treated slides (Fig. 4) the intensity of ICG was increased about 7-fold in the regions with laser-deposited silver. The extent of the ICG enhancement was variable from spot to spot, or within a single spot, with some regions displaying much greater increases in intensity, which appeared to depend on the optical density of the spot. It was generally observed, within a single spot, that the ICG intensity increased towards the center of the spot, although no qualitative data is available due to the diameter of the excitation beam with respect to that of the spot itself. We do, however, speculate that the enhancement is likely to follow the Gaussian nature of the beam pro le.

Fig. 4.

(Top) Fluorescence intensity of HSA–ICG coated glass, IG, and laser deposited silver, IS (442 nm, 15 min exposure). (Bottom) Fluorescence intensities normalized to the intensity on silver.

Fluorescent probes frequently display increases in intensity when bound in a rigid environment. In such cases, the increased intensity is due to a decrease in the non-radiative decay rates, knr, so that the lifetime also increases:

| (5) |

In contrast, the increased intensities due to a metallic surface, Q m, are due to an increase in the radiative decay rate (Γ + Γm) and thus result in an increase in quantum yield (number of photons emitted vs. number of photons absorbed) and decreased lifetime, τm:

| (6) |

| (7) |

For completeness we note that other effects of metals are possible including quenching and increased rates of excitation.

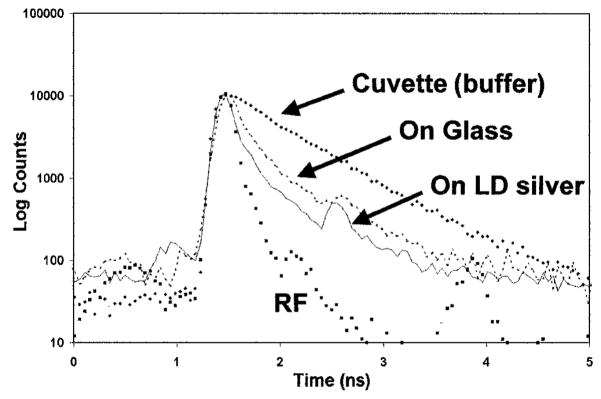

To distinguish between increases in knr or increase in Γm we examined the intensity decays of ICG–HSA (Fig. 5). The intensity decay is more rapid on glass than in solution. This effect has been observed previously but we presently have no explanation. More importantly, there is a much more dramatic decrease in the decay times when ICG–HSA is bound to laser-deposited silver (Fig. 5 and Table I). The decrease in the decay times τ̄ and <τ> are due to a very short ~6 ps component in the decay, with the other minor components similar to that observed on glass. Control measurements showed that scattered light did not contribute to the intensity decays and therefore were not the origin of the shorter components of the decay. We interpret the short component as due to ICG molecules at approximate distances from the silver surfaces to result in a dramatically increased radiative decay rate and the longer component to ICG molecules that are more distant from the silver surfaces. The fact that the lifetimes decreased indicates that at least part of the intensity increase is due to faster radiative decay and not to an increased rate of excitation.

Fig. 5.

Time-dependent intensity decays of ICG–HSA in solution (buffer), bound to glass, and on laser-deposited (LD) silver. (RF) Instrumental response function <40 ps FWHM.

TABLE I.

Analysis of the intensity decay of ICG–HSA in buffer, on glass, and on laser-deposited silver, measured using the reverse start-stop time-correlated single-photon-counting technique. The data was analyzed in terms of the multi-exponential model, c.f. Eq. 1.

| Sample | αi | τi (ns) | fi | τ̄(ns) | 〈τ〉(ns) | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Buffer | 0.158 | 0.190 | 0.05 | … | … | |

| 0.842 | 0.615 | 0.95 | 0.592 | 0.548 | 1.4 | |

| On Glass | 0.655 | 0.078 | 0.205 | … | … | |

| 0.345 | 0.578 | 0.795 | 0.476 | 0.251 | 0.92 | |

| Laser deposited Ag | 0.999 | 0.006 | 0.157 | … | … | |

| 0.004 | 0.146 | 0.165 | … | … | ||

| 0.006 | 0.399 | 0.678 | 0.296 | 0.035 | 1.08 |

We also examined the photostability of ICG–HSA when bound to glass or laser-deposited silver. We reasoned that ICG molecules with shortened lifetimes should be more photostable because there is less time for photochemical processes to occur. The intensity of ICG–HSA was recorded with continuous illumination at 760 nm. When excited with the same incident power, the fluorescence intensities, when considered on the same intensity scale, decreased somewhat more rapidly on the silver (Fig. 6, top). However, the difference is minor. Since the observable intensity of the ICG molecules prior to photobleaching is given by the area under these curves, it is evident that at least 10-fold more signal can be observed from ICG near silver as compared to glass. Alternatively, one can consider the photostability of ICG when the incident intensity is adjusted to result in the same signal intensities on silver and glass. In this case (Fig. 6, bottom) photobleaching is slower on the silver surfaces. The fact that the photobleaching is not accelerated for ICG or silver indicates that the increased intensities on silver are not due to an increased rate of excitation.

Fig. 6.

(Top) Photostability of ICG–HSA on (G) glass, and (S) laser-deposited silver, measured with the same excitation power at 760 nm, and (Bottom) with the laser power at 760 nm adjusted for the same initial fluorescence intensity. Laser-deposited samples were made by focusing 442 nm laser light onto APS coated glass slides immersed in a AgNO3 citrate solution for 15 min. The OD of the sample was ~0.3.

Finally, we investigated the possibility of using an inverted microscope to laser-deposit silver on APS treated slides, with the intention of producing signi cantly smaller spots than the 0.5 cm diameter spots obtained with the 8 mW illumination using the HeCd source (Fig. 2). By adapting an inverted microscope, Axiovert 135 TV (Fig. 7, top) and using a 10× 0.4 NA objective, we were able to rapidly produce laser-deposited spots of the order of 50 μm in diameter (Fig. 7, bottom), with different optical densities depending on the time of illumination. If the slides were not treated with APS, silver was deposited. However, the silver was less strongly bound to the glass surface and could be removed with washing. Interestingly, due to the increased irradiance of the focused light, ~560 W/cm2, the silver now deposited much faster on the slides (Fig. 7). This suggests the application of highly focused light for the laser deposition of silver over very small areas and, indeed, in a very short time frame. The speed of this silver lithographic process may therefore aid its introduction into MEF technologies, which may in the future require mass production, such as disposable sensors, gene chips, or microfluidic-type devices.

Fig. 7.

(Top) Inverted Axiovert 135 TV micrcoscope with epi-illumination for LD and, (Bottom) image of silver spots, produced by LD, using transmitted light illumination. The diameter of a spot is typically 50 μm. The irradiance was 560 W/cm2 with a 40×, NA 1.2 objective. Images (A–F) were taken 5 s apart.

DISCUSSION

In our opinion, metal-enhanced fluorescence from light-deposited silver can have numerous applications in analytical chemistry, medical diagnostics, and biotechnology. One immediate application could be to micro-fluidic devices such as the “lab on a chip”.25–29 In these devices there are typically spatially separate mixing and detector locations. One can imagine the detection areas being illuminated to deposit silver for increased detection sensitivity, particularly for low-quantum-yield fluorophores, which are preferentially enhanced near silver particles.1–4,30 This approach could also be applied to other fluorescence systems such as flow DNA analysis or single-molecule DNA sequencing.31–34

Another potential application of light-deposited silver could be on gene chips or DNA arrays.35,36 In this application, photolithography is already in use for spatially directed synthesis of the DNA oligomers.37 Hence, it may be possible to introduce illumination steps that would deposit silver at the desired locations. Alternatively, methods are known for microcontact printing of silane reagents onto glass, providing the desired spatial distribution of amino groups.38 One could then illuminate the entire device and obtain deposition of the colloids on the amine-coated regions. Our observation of enhanced fluorescence with light-deposited silver extends the range of applications of metal-enhanced fluorescence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH, National Center for Research Resources, RR-08119.

References

- 1.Lakowicz JR. Anal Biochem. 2001;298:1. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakowicz JR, Shen Y, D’Auria S, Malicka J, Fang J, Gryczynski Z, Gryczynski I. Anal Biochem. 2002;301:261. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakowicz JR, Shen Y, Gryczynski Z, D’Auria S, Gryczynski I. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:875. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gryczynski I, Malicka J, Shen Y, Gryczynski Z, Lakowicz JR. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:2191. doi: 10.1021/jp013013n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gersten J, Nitzan A. J Chem Phys. 1981;75:1139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weitz DA, Garoff S. J Chem Phys. 1983;78:5324. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kummerlen J, Leitner A, Brunner H, Aussenegg FR, Wokaun A. Mol Phys. 1983;80:1031. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell WC, Myrick ML. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;242:300. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez-Gattorno G, Diaz D, Rendon L, Hernandez-Segura GO. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:2482. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abid JP, Wark AW, Breve PF, Girault HH. Chem Commun. 2002;7:792. doi: 10.1039/b200272h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pastoriza-Santos I, Serra-Rodriguez C, Liz-Marzan LM. J Collloid Interface Sci. 2002;221:236. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schutt F, Fischer J, Kopitz J, Holz FG. Clin Exp Invest. 2002;30(2):110. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-6404.2002.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marengo J, Ucha RA, Martinez-Cartier M, Sampaolesi JR. Int Ophthalmology. 2001;23:413. doi: 10.1023/a:1014431404096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishihara H, Okawa H, Iwakawa T, Umegaki N, Tsubo T, Matsuki A. Anesthesia Analgesia. 2002;94:781. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakka SG, Reinhart K, Wegscheider K, Meier-Hellmann A. Chest. 2002;121:559. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanzetta P. Retina J Ret VIT Dis. 2001;21:563. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200110000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sevick-Muraca EM, Lopez G, Reynolds JS, Troy TL, Hutchinson CL. Photochem Photobiol. 1997;66:55. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb03138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devoisselle JM, Soulie S, Maillols H, Desmettre T, Mordon S. Proc SPIE-Int Soc Opt Eng. 1997;2980:293. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devoisselle JM, Soulie S, Mordon S, Desmettre T, Maillols H. Proc SPIE-Int Soc Opt Eng. 1997;2980:453. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker A, Riefke B, Ebert B, Sukowski U, Rinneberg H, Semmier W, Licha K. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;72:234. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)072<0234:mcafoi>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sokolov K, Chumanov G, Cotton TM. Anal Chem. 1998;70:3898. doi: 10.1021/ac9712310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Tan W, Wang K, Xiao D, Yang X, He X, Tang Z. Anal Sci. 2001;17:1149. doi: 10.2116/analsci.17.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malicka J, Gryczynski I, Geddes CD, Lakowicz JR. J Biomed Opt. 2003 doi: 10.1117/1.1578643. paper in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni F, Cotton TM. Anal Chem. 1986;58:3159. doi: 10.1021/ac00127a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Rauch CB, Stevens RL, Lenigk R, Yang J, Rhine DB, Grodzinski P. Anal Chem. 2002;74:3063. doi: 10.1021/ac020094q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yakovleva J, Davidsson R, Lobanova A, Bengtsson M, Eremin S, Laurell T, Emmeus J. Anal Chem. 2002;74:2994. doi: 10.1021/ac015645b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verpoorte E. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:677. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200203)23:5<677::AID-ELPS677>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson RC, Su X, Bogdan GJ, Fenton J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(12):e60–eoa. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallraff G, Labadie J, Brock P, DiPietro R, Nguyen T, Huynh T, Hinsberg W, McGall G. Chemtech. 1997;27:22. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schalkhammer T, Aussenegg FR, Leitner A, Brunner H, Hawa G, Lobmaier C, Pittmer F. Proc SPIE-Int Soc Opt Eng. 1997;2976:129. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Orden A, Machara NP, Goodwin PM, Keller RA. Anal Chem. 1998;70:1444. doi: 10.1021/ac970545k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Orden A, Keller RA, Ambrose WP. Anal Chem. 2000;72:37. doi: 10.1021/ac990782i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauer M, Angerer B, Ankenbauer W, Foldes-Papp Z, Gobel F, Hanb KT, Rigler R, Schulz A, Wolfrum J, Zander C. J Biotechnol. 2001;86:181. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(00)00413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephan J, Dorre K, Brakmann S, Winkler T, Wetzel T, Lapczyna M, Stuke M, Angerer B, Ankenbauer W, Foldes-Papp Z, Rigler R, Eigen M. J Biotechnol. 2001;86:255. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(00)00417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schena M, Heller RA, Theriault TP, Konrad K, Lachenmeier E, Davis RW. Tibtech. 1998;16:301. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown PO, Botstein D. Nat Genet (Supp) 1999;21:33. doi: 10.1038/4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipschutz RJ, Fodor SPA, Gingeras TR, Lockhart DJ. Nat Genet (Supp) 1999;21:20. doi: 10.1038/4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biju V, Gad M, Mizutani W, Murata S, Ishikawa M. J Imaging Sci Technol. 2002;46:155. [Google Scholar]