Abstract

We assessed the relations of genetic and environmental factors in the etiology of epilepsy. The study population comprised 9,705 first-degree relatives of 1,951 adults with epilepsy ascertained from voluntary organizations. We calculated standardized morbidity ratios for specific etiologies of epilepsy in the relatives of probands with the same etiologies, using population incidence rates from Rochester, MN, as the reference. Relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy had increased risk for idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy and for epilepsy associated with neurological deficit presumed present at birth (cerebral palsy or mental retardation) but not for symptomatic epilepsy associated with postnatal central nervous system insults. Relatives of probands with neurodeficits had increased risks for idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy. Risk for epilepsy was not increased among relatives of probands with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy. The degree of increased risk of idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy in relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy diminished with increasing age of the relatives; risk was not increased at age 35 or older. These findings support the possibility of a shared genetic susceptibility to epilepsy and cerebral palsy, and suggest that the genetic contributions to postnatal symptomatic epilepsy are minimal.

The importance of inheritance in the etiology of epilepsy is well established, but the underlying genetic mechanisms remain poorly understood. One important question is the degree to which genetic susceptibility contributes to epilepsy following an identified environmental insult. This study uses an epidemiologic approach to address this question.

Approximately 25% of prevalent epilepsy is associated with an antecedent central nervous system (CNS) injury (eg, head trauma, stroke, or brain infection) and accordingly is classified as “symptomatic” [1]. The remainder without identified cause is assigned by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification of epilepsy syndromes [2] into two broad classes, “idiopathic,” reserved for syndromes of presumed genetic origin, and “cryptogenic,” for syndromes presumed to be nongenetic but with insufficient evidence to assign a specific etiology.

Risks of epilepsy are reportedly lower in relatives of probands with symptomatic epilepsy than in relatives of those with idiopathic or cryptogenic epilepsy [3–7]. In the classic twin study of epilepsy by Lennox [3], the difference in concordance rates between monozygotic and dizygotic twins was smaller when the index twin’s epilepsy was symptomatic than when it was idiopathic or cryptogenic. In our recent study [8], risk of epilepsy was higher in relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy than in relatives of probands with symptomatic epilepsy. An exception to this pattern, however, was the subgroup of symptomatic epilepsy associated with neurodeficit from birth. Risks of epilepsy were higher in relatives of probands with cerebral palsy or mental retardation than in relatives of probands with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy.

Within each of the three etiologic classes currently used in the syndrome classification (idiopathic, cryptogenic, and symptomatic) [2], both genetic and environmental factors may contribute to etiology. For example, in syndromes strongly influenced by genetic susceptibility, some environmental exposures may exacerbate the effect of the susceptibility genotype or may be required for gene expression. On the other hand, some genetic influences on susceptibility to epilepsy may generally lower seizure threshold, so that some symptomatic epilepsies or even acute symptomatic seizures may involve a genetic susceptibility. With posttraumatic epilepsy, for example, less severe head injuries might produce epilepsy in persons with a genetic susceptibility than in the general population. In this study, we investigate the relations between genetic and environmental factors in the etiology of epilepsy further, by examining risks of specific etiologies of epilepsy in the relatives of probands with the same specific etiologies.

Subjects and Methods

Study Population

The study population comprised first-degree relatives of probands with epilepsy from the Epilepsy Family Study of Columbia University (EFSCU). The methods for data collection in this study have been described in detail previously [9]. In brief, 1,957 adults with epilepsy (probands) were ascertained from voluntary organizations with 84% participation. We used semistructured telephone interviews with probands to obtain information on clinical characteristics of epilepsy and history of seizure disorders and related conditions in parents, full siblings, half-siblings, offspring, and spouses. Whenever possible (67% of families), we also interviewed an additional family informant (usually the mother of the proband) about the same relatives reported on by the proband, to improve the sensitivity of the family history data. To confirm and augment the clinical detail on the family histories, we were also able to interview 51% of living adult relatives who were reported to have had seizures when they were ≥5 years old. We obtained medical records for 60% of probands.

Eighty-seven percent of probands were white, 55% had ≥1 year of college education, and 60% were women. Subjects interviewed did not differ in sex or ethnicity from those who refused but were more educated. Probands ranged in age from 18 to 82 years and averaged 36 years. All of the probands had intelligence sufficiently high to answer the interview questions, and none was severely retarded.

Clinical Diagnoses in Probands and Family Members

Diagnoses of seizure disorders were based on a review of all information collected on each proband or relative (proband interview, second informant interview, direct interview, and/or medical record). Epilepsy was defined as a lifetime history of two or more unprovoked seizures [1]. The proband’s family history report of epilepsy in parents and siblings had excellent validity (sensitivity, 87%; specificity, 99%), using the mother’s report as the gold standard [10]. We classified seizures according to the 1981 criteria of the ILAE [11], distinguishing between generalized onset and partial onset seizures. Using the current classification of epileptic syndromes [2], patients with generalized onset seizures would be classified as having generalized epilepsies, and those with partial onset seizures would be classified as having localization-related epilepsies. As we have reported previously, the resulting seizure classifications were reliable [12] and valid, compared with diagnoses of physicians with expertise in epilepsy [13]. We also classified epilepsy in both probands and affected relatives by age at onset and presumed etiology, according to standardized criteria [1].

We obtained data for classification of seizure type and etiology of epilepsy in the interviews with the probands and other family informants, supplemented by review of medical records whenever possible. As previously described [12, 13], the data for seizure classification included verbatim descriptions of seizures and closed-ended questions regarding relevant features (eg, specific aura, unilateral signs, alteration in consciousness, and so on). For classification of etiology, we asked specific questions about factors demonstrated to be strongly associated with risk for epilepsy in previous epidemiologic studies, including severe head injury (defined as injury associated with ≥30 minutes of loss of consciousness or skull fracture) [14], stroke, brain tumor, brain surgery, brain infection (specifically, spinal meningitis or encephalitis), and cerebral palsy. When a history of one of these factors was reported, we inquired about the age at which it occurred, whether seizures had occurred in close temporal association, and how long after the event the seizures had occurred. Seizures occurring <7 days after the event were not considered epilepsy but were classified as acute symptomatic. (Subjects who had had only acute symptomatic seizures were not eligible to be probands, but some of the relatives had had only acute symptomatic seizures.) We also asked about other factors potentially associated with seizures, including heavy alcohol drinking, diabetes, high blood pressure, paralysis, attendance at a special school because of a learning difficulty, and any other serious medical problem. We used this information to discriminate further between acute symptomatic and unprovoked seizures, and to clarify the etiology of epilepsy.

Probands were asked about clinical manifestations and etiology of seizures with respect to themselves and any other relative they reported to have had seizures. The interviews with other family informants included the same questions about seizure type and etiology in the proband, the relative who was being interviewed, and any other relatives reported by the second informant to have had seizures. The final classification of seizure type and etiology was made on the basis of a case-by-case review of all of this information.

For the present analysis, we used the following three categories of etiology: idiopathic/cryptogenic—epilepsy occurring in the absence of a historical insult to the CNS demonstrated to increase greatly the risk of unprovoked seizures; neurological deficit presumed present at birth (neurodeficit from birth)—epilepsy associated with a history of cerebral palsy (motor handicap or movement disorder) or mental retardation (IQ < 70) presumed present at birth; and postnatal symptomatic—epilepsy associated with a history of a postnatal CNS insult occurring ≥7 days prior to the first unprovoked seizure. Among all 1,957 probands, the etiology of epilepsy was idiopathic/cryptogenic in 1,560 (80%), neurodeficit in 29 (28 cerebral palsy, 1 mildly intellectually impaired) (1%), postnatal symptomatic in 362 (vascular, 36; posttraumatic, 157; infectious, 113; neoplastic, 25; other, 31) (18%), and unclassifiable in 6 (0.3%).

Statistical Analysis

We assumed that each relative was at risk of epilepsy from birth until current age or age at death (if unaffected) or age at first unprovoked seizure (if affected with epilepsy). We calculated standardized morbidity ratios (SMRs), using incidence rates from Rochester, MN, 1935 to 1984, as the reference [15]. For this purpose, we calculated each relative’s age-specific person-years at risk of epilepsy within each of four secular periods (prior to 1955, 1955–1964, 1965–1974, and 1975 or later), and summed these across all relatives. Then we applied the age- and decade-specific incidence rates of idiopathic/cryptogenic, neurodeficit, and postnatal symptomatic epilepsy in Rochester to the summed person-years to obtain the number of relatives expected to have onset of each etiology of epilepsy in each age category within each secular period. We calculated SMRs and their confidence intervals according to the formulas given by Haenszel and colleagues [16]. In the calculation of the expected numbers for epilepsy associated with neurodeficit, person-years of observation in the parents of the probands were excluded because of the low probability of reproduction (and hence, becoming a parent of a proband) in persons with neurological deficits.

We excluded the families of the 6 probands with missing information on etiology of epilepsy. Among all 10,734 first-degree relatives of the remaining 1,951 probands, 1,024 (10%) were excluded because of missing information either about history of epilepsy or birth year (parents, 14%; siblings, 8%; offspring, 6%). Among the remaining 9,710 relatives, 269 (2.8%) had epilepsy. Five (2%) of the relatives with epilepsy were excluded because the etiology of epilepsy was unknown (n = 4), or epilepsy was associated with neurodeficit in a parent (n = 1) (since parents were excluded from the analysis of epilepsy associated with neurodeficit). These exclusions left 9,705 relatives for the present analysis, of whom 264 had epilepsy.

Results

We examined the SMRs for relatives of probands with idopathic/cryptogenic, neurodeficit, and postnatal symptomatic epilepsy, within strata defined by the time period at risk in the relatives (Table 1). All of the SMRs were much lower for risk periods prior to 1955 than for more recent periods, reflecting underreporting of epilepsy incidence in relatives many years prior to interview, as we have noted previously [17]. Because of this underreporting, we restricted the remaining analyses to risk periods in 1955 or later. Incidence did not differ substantially across the other three time periods examined (1955–1964, 1965–1974, and 1975 or later).

Table 1.

Standardized Morbidity Ratios (SMRs) for Epilepsy in First-Degree Relatives of Probands with Idiopathic/Cryptogenic, Neurodeficit, and Postnatal Symptomatic Epilepsy, by Time Period of Risk in Relatives

| Number with of Relatives Epilepsy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etiology of Epilepsy in Probands | Period of Risk in Relatives | Observed | Expecteda | SMR (95% CI) |

| Idiopathic/cryptogenic | Prior to 1955 | 54 | 56.9 | 0.9 (0.72–1.25) |

| 1955–1964 | 49 | 23.9 | 2.1 (1.52–2.71) | |

| 1965–1974 | 73 | 19.9 | 3.7 (2.90–4.64) | |

| 1975 or later | 58 | 32.3 | 1.8 (1.38–2.34) | |

| Total 1955 or later | 180 | 76.1 | 2.4 (2.04–2.74) | |

| Neurodeficit from birth | Prior to 1955 | 2 | 0.9 | 2.2 (0.27–8.02) |

| 1955–1964 | 0 | 0.4 | — | |

| 1965–1974 | 2 | 0.3 | 6.7 (0.81–24.07) | |

| 1975 or later | 2 | 0.5 | 4.0 (0.48–14.44) | |

| Total 1955 or later | 4 | 1.3 | 3.1 (0.84–7.88) | |

| Postnatal symptomatic | Prior to 1955 | 5 | 14.0 | 0.4 (0.12–0.83) |

| 1955–1964 | 8 | 5.8 | 1.4 (0.59–2.72) | |

| 1965–1974 | 2 | 4.8 | 0.4 (0.05–1.50) | |

| 1975 or later | 9 | 7.8 | 1.2 (0.53–2.19) | |

| Total 1955 or later | 19 | 18.4 | 1.0 (0.62–1.61) | |

Expected numbers based on age- and decade-specific incidence rates of epilepsy in Rochester. MN, population, 1945–1984 [15].

CI = confidence interval.

In 1955 or later, risk for all epilepsy was increased 2.4-fold among relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy and 3.1-fold among relatives of probands with neurodeficits. Risk was not increased among relatives of probands with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy (SMR = 1.0).

Among relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy, risk was increased for idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy (SMR = 3.0) and for epilepsy associated with neurodeficits (SMR = 2.1) but not for postnatal symptomatic epilepsy (Table 2). Among relatives of probands with neurodeficits, risk was increased for idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy (SMR = 3.8), although there were few person-years of observation in this stratum. Among relatives of probands with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy, risk was not significantly increased for either idiopathic/cryptogenic, neurodeficit, or postnatal symptomatic epilepsy (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Standardized Morbidity Ratios (SMRs) for Idiopathic/Cryptogenic, Neurodeficit, and Postnatal Symptomatic Epilepsy in First-Degree Relatives of Probands with these Etiologies of Epilepsy (1955 or Later Only)

| Etiology of Epilepsy in |

Number of Relatives with Epilepsy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probands | Relatives | Observed | Expecteda | SMR (95% CI) |

| Idiopathic/cryptogenic | Idiopathic/cryptogenic | 149 | 49.5 | 3.0 (2.55–3.54) |

| Neurodeficit from birthb | 10 | 4.7 | 2.1 (1.02–3.91) | |

| Postnatal symptomatic | 21 | 21.9 | 1.0 (0.59–1.47) | |

| Neurodeficit from birth | Idiopathic/cryptogenic | 3 | 0.8 | 3.8 (0.77–10.95) |

| Neurodeficit from birthb | 1 | 0.1 | 10.0 (0.25–55.70) | |

| Postnatal symptomatic | 0 | 0.4 | — | |

| Postnatal symptomatic | Idiopathic/cryptogenic | 17 | 12.0 | 1.4 (0.83–2.27) |

| Neurodeficit from birthb | 0 | 1.1 | — | |

| Postnatal symptomatic | 2 | 5.3 | 0.4 (0.05–1.36) | |

Expected numbers based on age- and decade-specific incidence rates of specific etiologies of epilepsy in Rochester, MN, population, 1945–1984 [15].

Parents excluded from calculation of SMRs for epilepsy associated with neurodeficit.

CI = confidence interval.

We also examined the SMRs for idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy in relatives of probands with specific categories of postnatal symptomatic epilepsy (Table 3). The observed and expected numbers of affected relatives did not differ substantially for any etiology of epilepsy in the probands.

Table 3.

Standardized Morbidity Ratios (SMRs) for Idiopathic/Cryptogenic Epilepsy in Relatives of Probands with Postnatal Symptomatic Epilepsy, by Specific Etiology of Epilepsy in the Proband (1955 or Later Only)

| Number of Relatives with Idiopathic/Cryptogenic Epilepsy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Etiology of Epilepsy in Probands | Observed | Expecteda | SMR (95% CI) |

| Vascular | 2 | 1.2 | 1.7 (0.20–6.02) |

| Posttraumatic | 9 | 5.2 | 1.7 (0.79–3.29) |

| Infectious | 3 | 3.5 | 0.8 (0.18–2.50) |

| Neoplastic | 1 | 1.1 | 0.9 (0.02–5.06) |

| Other | 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 (0.24–7.22) |

Expected numbers based on age- and decade-specific incidence rates of idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy in Rochester, MN, population, 1955–1984 [15].

CI = confidence interval.

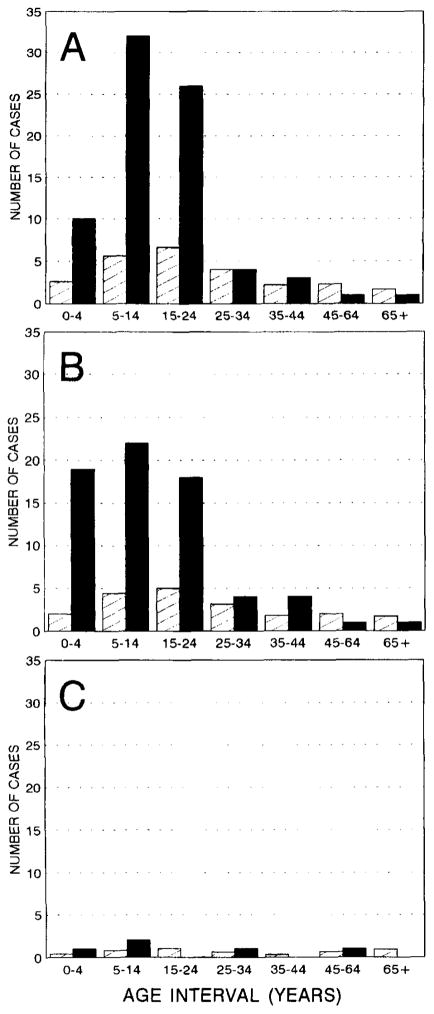

We examined the SMRs for idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy in relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy, by age at onset in probands and relatives (<15, 15–34, and ≥35 years) (Fig and Table 4). For all three categories of age at onset in probands, the degree of increased risk diminished with increasing age at risk of the relatives (see Fig). Among relatives of probands with onset prior to age 15, for example, the SMR was 5.0 for onset of epilepsy prior to age 15, 2.8 for onset from age 15 to 34, and 0.8 for onset at age 35 or older (see Table 4). The incidence of epilepsy was not increased at age 35 or older in the relatives, regardless of age at onset of the proband. The SMRs were similar in relatives of probands with onset at <15 and 15 to 34 years. Among relatives of probands with onset at 35 years or later, however, risk of epilepsy was not significantly increased.

Fig.

Observed (black bars) and expected (hatched bars) number of persons with onset of idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy during specific age intervals, among relatives of probands with onset of idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy < 15 years (A), 15 to 34 years (B), and ≥ 35 years (C) (1955 or later only). Expected numbers were based on age- and decade-specific incidence rates in Rochester, MN, population, 1955 to 1984 [15].

Table 4.

Standardized Morbidity Ratios (SMRs) for Idiopathic/Cryptogenic Epilepsy in Relatives of Probands with Idiopathic/Cryptogenic Epilepsy, by Age at Onset of Probands and Relatives (1955 or Later Only)

| Number of Relatives with Epilepsy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Onset in Proband (yr) | Age at Onset in Relatives (yr) | Observed | Expecteda | SMR (95% CI) |

| <15 | <15 | 41 | 8.2 | 5.0 (3.59–6.80) |

| 15–34 | 30 | 10.6 | 2.8 (1.91–4.05) | |

| ≥35 | 5 | 6.2 | 0.8 (0.26–1.88) | |

| Total | 76 | 25.0 | 3.0 (2.41–3.83) | |

| 15–34 | <15 | 41 | 6.4 | 6.4 (4.59–8.71) |

| 15–34 | 21 | 8.1 | 2.6 (1.60–3.97) | |

| ≥35 | 6 | 5.5 | 1.1 (0.40–2.38) | |

| Total | 68 | 20.0 | 3.4 (2.66–4.34) | |

| ≥35 | <15 | 3 | 1.2 | 2.5 (0.52–7.30) |

| 15–34 | 1 | 1.6 | 0.6 (0.02–3.48) | |

| ≥35 | 1 | 1.8 | 0.6 (0.01–3.09) | |

| Total | 5 | 4.6 | 1.1 (0.35–2.53) | |

Expected numbers based on age- and decade-specific incidence rates of idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy in Rochester, MN, population, 1955–1984 [15].

CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

In this study, we extended our previous investigations of epilepsy in the families of probands from the EFSCU [8, 17], by evaluating the relations between genetic and environmental factors in their effects on risk. For this purpose, we computed SMRs for specific etiologies of epilepsy in the relatives of probands with specific etiologies, using age- and decade-specific incidence of epilepsy from the Rochester-Olmsted County Record Linkage Project as the reference. This approach differs from our previous analyses in three ways. First, we used an external control population (the Rochester incidence rates), rather than relying on internal comparisons among the families of subgroups of probands. This allowed us to evaluate, for each subgroup, the degree of increased risk compared with the general population, in addition to the differences across subgroups in familial risk. Second, we examined risks for specific etiologies of epilepsy in the relatives, as well as in the probands. Third, we stratified by secular period of risk in the relatives, and thus examined directly the effect of underreporting of epilepsy in remote time periods. We have described an apparent “cohort effect” in familial risk of epilepsy, with higher lifetime prevalence in younger relatives [17]. Data from Rochester [15] indicate that incidence of epilepsy has not increased in individuals younger than age 40 during the time periods we investigated; thus, we concluded that the apparent cohort effect is likely to be due to underreporting of epilepsy that was present at young ages in older relatives. In previous analyses, we have controlled for this underreporting by adding birth year of the relatives as a covariate [8]. Analysis restricted to the period after 1955 allows a more refined control for underreporting, because regardless of the birth year of the relatives, we expect less underreporting of epilepsy for recent time periods than for those in the past. As expected, we found markedly lower SMRs for periods prior to 1955 than for more recent periods (see Table 1).

Since the average birth year of the probands was 1951, restriction of the analysis to 1955 or later also restricts most of the person-time of follow-up to periods after the birth of the proband. This is important for analysis of epilepsy risks in the parents. Incidence of epilepsy is lower in individuals who survive and reproduce than in the general population; hence, it would not be appropriate to use population incidence rates to compute the expected number of parents who had onset of epilepsy prior to birth of the proband. Restriction of the analysis to periods after the proband’s birth substantially controls for these effects, although expected rates of epilepsy in the parents also remain slightly reduced after the birth of the proband, because of reduced reproduction in persons with epilepsy [18]. The expected rates of epilepsy in siblings and offspring are not influenced by these effects of survival and reproduction.

Our results indicate that the etiology of epilepsy in the proband is an important index of epilepsy risk in family members. Among relatives of probands without identified CNS insults (ie, idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy), risk was increased 2.4-fold overall (see Table 1) and 3.0-fold for idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy (see Table 2). The degree of increased risk of idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy was greater at younger ages than at older ages, and disappeared entirely by the time the relatives reached age 35. Also, there was no increased risk among relatives of probands with onset at 35 years or later.

Among relatives of probands with epilepsy associated with neurological deficits presumed present at birth, the SMR was as high as that for relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy (3.1-fold, see Table 1), and this increased risk persisted when the outcome in the relatives was restricted to idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy (3.8-fold, see Table 2). In addition, risk was significantly increased for epilepsy associated with neurodeficits among relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy (2.1-fold, see Table 2). The consistency of these findings provides support for the possibility of a shared genetic susceptibility to epilepsy and cerebral palsy, as we and others have suggested [8, 19–21].

Risk of epilepsy was not increased among relatives of probands with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy. Schaumann and associates [22] also reported that risk was not increased in relatives of probands with post-traumatic epilepsy. In that study, however, risk was increased in relatives of probands who had seizures associated with alcohol, whether unprovoked seizures or epilepsy associated with chronic alcohol abuse, or acute symptomatic seizures associated with alcohol intoxication. We did not have sufficient data to examine the alcohol subgroup separately.

These findings provide clues about the relations between genetic susceptibility and environmental risk factors in their influence on epilepsy risk. Here we consider two (among many) possible relations between genotype and environment [23–25]. Under an additive model, an environmental risk factor adds the same amount to the risk of epilepsy, regardless of whether a person is genetically susceptible. Under a multiplicative model, the environmental insult multiplies the risk by the same amount in susceptibles and nonsusceptibles. Under the additive model, probands who develop epilepsy in the absence of environmental insults (ie, those with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy) are more likely to be genetically susceptible than those with identified insults. In contrast, under the multiplicative model, probands with epilepsy have the same likelihood of being genetically susceptible regardless of whether they were exposed to an environmental insult [24, 25].

The data on risks of idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy in relatives, within strata defined by the etiology of epilepsy in probands, allow us to reject the multiplicative model. Relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy have increased risk of idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy, but relatives of probands with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy do not (see Table 2). Hence, probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy are more likely to be genetically susceptible than those with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy.

These results have implications for the design of genetic linkage studies of the epilepsies. They suggest that in families segregating a major gene increasing susceptibility to epilepsy, persons with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy are no more likely than unaffected individuals to be carriers of the susceptibility gene. In our effort to localize a susceptibility gene for partial epilepsy with auditory features to chromosome 10q [26], we used a conservative approach and classified individuals with symptomatic epilepsies as “unknown” with respect to the phenotype assumed to result from the susceptibility gene.

Probands in our series (adults with epilepsy who contacted voluntary organizations for epilepsy) are unrepresentative of the general population of persons with epilepsy in terms of seizure type. The proportion with partial onset seizures (84%) is higher than in prevalent cases of all ages in Rochester (59%) [1] but is similar to that in other series of adults with epilepsy ascertained from clinical care settings (74–83%) [27–30]. However, the distribution of etiologies among probands in our sample is similar to the distribution in prevalent epilepsy cases in Rochester (eg, Rochester vs EFSCU: idiopathic/cryptogenic, 76% vs 80%; post-traumatic, 5% vs 8%; cerebrovascular, 6% vs 2%; infection, 4% vs 6%) [1]. The distribution of age at onset is also similar to Rochester prevalence cases (Rochester vs EFSCU: <10 years, 31% vs 28%; 10–19 years, 33% vs 39%; ≥20 years, 36% vs 33%) [1].

Because our probands are adult prevalent epilepsy cases, persons with childhood onset epilepsies that remit before adulthood, many of which are associated with high familial risk, were largely excluded from our sample of probands. This may have led to a different estimate of the impact of proband age at onset on familial risk than would be obtained in a proband sample of incident cases. Also, should the relations between genetic susceptibility and etiology of epilepsy prove to be different in childhood onset, remitting epilepsies than in those that persist with adulthood, the generalizability of our findings would be limited.

We did not assess the validity of the information on etiology of epilepsy collected through interviews with probands and relatives. We attempted to maximize validity through the use of a structured interview, with specific questions aimed at factors known to be strongly associated with epilepsy risk, and review of medical records whenever possible. The similarity of the distribution of etiologies in probands to that in prevalent cases in Rochester provides some reassurance about this. However, some histories of CNS insults could have been missed. If so, we could have underestimated the SMRs in relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy.

In our study, all but 1 of the probands classified as having neurodeficit had cerebral palsy. Further, none of the probands in this subgroup had severe intellectual impairment, because participation required intelligence sufficiently high to be able to answer the interview questions. This would have reduced comparability of our series with other series of patients with epilepsy associated with neurological deficits presumed present at birth.

We were unable to obtain obstetrical records on the probands with neurological deficits from birth (all of whom were aged 18 or older), to assess the possible causes of their cerebral palsy. In prospective data from the National Collaborative Perinatal Project, incidence of cerebral palsy was associated with obstetric complications only in infants who also had low Apgar scores, and these infants comprised only 13% of those with cerebral palsy [31]. Further, even in infants with low Apgar scores, underlying defects that predated labor may have been present in some cases. Thus, cerebral palsy, like idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy, is essentially a disorder of unknown etiology. It is associated with epilepsy but is not a direct cause. This is quite different from the postnatal symptomatic etiologies of epilepsy, which involve an identified CNS insult occurring at a discrete time (eg, head trauma, stroke, brain infection). This difference may explain our observations, which suggest that some genetic influences are common to epilepsy and cerebral palsy, whereas postnatal symptomatic epilepsy is primarily environmental in origin.

We combined epilepsies that would be classified, according to the current syndrome classification, as “idiopathic” and “cryptogenic,” because both occur in the absence of identified CNS insults. However, very few of the probands in our series had idiopathic epilepsy syndromes, and the vast majority of those without identified CNS insults would be classified as having cryptogenic epilepsy. Thus, the 2.4-fold increased risk of epilepsy in relatives of probands with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy (see Table 1) is essentially a measure of increased risk in relatives of persons with cryptogenic epilepsy. Assuming this increased risk reflects genetic susceptibility, this implies that the genetic influences on the epilepsies are not restricted to those classified as “idiopathic” but affect those classified as “cryptogenic” also.

We used population-based data from Rochester as a reference population, on the assumption that this would be an appropriate control group for the families of EFSCU probands. If the EFSCU probands were selected from a population with a different baseline epilepsy risk, or if there were substantial underreporting of epilepsy in relatives, we may have underestimated or overestimated the SMRs. Assuming the Rochester population is a reasonable control group, the similarity of observed and expected numbers of relatives with epilepsy in the families of probands with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy suggests that probands in this subgroup are unlikely to have a genetic susceptibility. Thus, the relatives of this subgroup of probands may provide a useful internal control group for subsequent analyses of this dataset.

Finally, these findings provide a basis for answering patients’ questions about the role of genetic factors in epilepsy. The increased risk for idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy among the relatives of patients with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy suggests that genetic susceptibility contributes to the etiology of epilepsy in these patients. This genetic susceptibility may also raise risk for epilepsy associated with neurological deficit presumed present at birth. The increased familial risk applies only to young ages; persons who reach age 35 without developing epilepsy do not have increased risk after that age. Patients with postnatal symptomatic epilepsy are unlikely to have a genetic susceptibility, and the risk of epilepsy is not increased in their relatives.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant RO1-NS20656.

References

- 1.Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Prevalence of epilepsy in Rochester, Minnesota: 1940–1980. Epilepsia. 1991;32:429–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1991.tb04675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia. 1989;30:389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lennox WG. The heredity of epilepsy as told by relatives and twins. JAMA. 1951;146:529–536. doi: 10.1001/jama.1951.03670060005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisner V, Pauli LL, Livingston S. Hereditary aspects of epilepsy. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1959;105:245–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuboi T, Endo S. Incidence of seizures and EEG abnormalities among offspring of epileptic patients. Hum Genet. 1977;36:173–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00273256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvald B. On the genetic prognosis of epilepsy. Acta Psychiatr Neurol. 1951;26:339–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1951.tb09678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Anderson VE. Epidemiology and the genetics of epilepsy. In: Ward AA, Penry JK, Purpura D, editors. Epidemiology and the genetics of epilepsy. New York: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 267–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ottman R, Lee JH, Risch N, et al. Clinical indicators of genetic susceptibility in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1996;37:353–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ottman R, Susser M. Data collection strategies in genetic epidemiology: the Epilepsy Family Study of Columbia University. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:72l–727. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90049-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ottman R, Hauser WA, Susser M. Validity of family history data on seizure disorders. Epilepsia. 1993;34:469–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 1981;22:489–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1981.tb06159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ottman R, Lee JH, Hauser WA, et al. Reliability of seizure classification using a semistructured interview. Neurology. 1993;43:2526–2530. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.12.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ottman R, Hauser WA, Stallone L. Semi-structured interview for seizure classification: agreement with physicians’ diagnoses. Epilepsia. 1990;31:110–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1990.tb05368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Annegers JF, Grabow JD, Groover RV, et al. Seizures after head trauma: a population study. Neurology. 1980;30:683–689. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.7.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia. 1993;34:453–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haenszel W, Loveland D, Sirken M. Lung cancer mortality as related to residence and smoking histories. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1962;28:1000–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottman R, Lee JH, Hauser WA, Risch N. Birth cohort and familial risk of epilepsy: the effect of diminished recall in studies of lifetime prevalence. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:235–241. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schupf N, Ottman R. The likelihood of pregnancy in individuals with idiopathic/cryptogenic epilepsy: social and biologic influences. Epilepsia. 1994;35:750–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Maternal seizure disorder, outcome of pregnancy, and neurologic abnormalities in the children. Neurology. 1982;32:1247–1254. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.11.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Antecedents of seizure disorders in early childhood. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:1053–1061. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140240099034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimoin DL, Metrakos JD. The genetics of convulsive disorders in the families of hemiplegics. Proc 2nd Intl Congr Hum Genet; Rome. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica Foundation; 1963. pp. 1655–1658. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaumann BA, Annegers JF, Johnson SB, et al. Family history of seizures in posttraumatic and alcohol-associated seizure disorders. Epilepsia. 1994;35:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ottman R. An epidemiologic approach to gene-environment interaction. Genet Epidemiol. 1990;7:177–185. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370070302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ottman R, Susser E, Meisner M. Control for environmental risk factors in assessing genetic effects on disease familial aggregation. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:298–309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ottman R. Epidemiologic analysis of gene-environment interaction in twins. Genet Epidemiol. 1994;11:75–86. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370110108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ottman R, Risch N, Hauser WA, et al. Localization of a gene for partial epilepsy to chromosome 10q. Nature Genet. 1995;10:56–60. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gastaut H, Gastaut JL, Concalves e Silva GE, Fernandez Sanchez GR. Relative frequency of different types of epilepsy: a study employing the classification of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1975;16:457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1975.tb06073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joshi V, Katiyar BC, Mohan PK, et al. Profile of epilepsy in a developing country: a study of 1,000 patients based on the international classification. Epilepsia. 1977;18:549–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1977.tb05003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alving J. Classification of the epilepsies: an investigation of 1,508 consecutive adult patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1978;58:205–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1978.tb02880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danesi MA. Classification of the epilepsies: an investigation of 945 patients in a developing country. Epilepsia. 1985;26:313–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1985.tb05396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Obstetric complications as risk factors for cerebral palsy or seizure disorders. JAMA. 1984;251:1843–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]