Abstract

In an open trial design, adults (n = 20) with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were treated via an 11-week cognitive-behavioral intervention for PTSD that consisted of education, anxiety management therapy, social skills training, and exposure therapy, provided at community mental health centers. Results offer preliminary hope for effective treatment of PTSD among adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, especially among treatment completers (n = 13). Data showed significant PTSD symptom improvement, maintained at 3-month follow-up. Further, 12 of 13 completers no longer met criteria for PTSD or were considered treatment responders. Clinical outcomes for other targeted domains (e.g., anger, general mental health) also improved and were maintained at 3-month follow-up. Participants evidenced high treatment satisfaction, with no adverse events. Significant improvements were not noted on depression, general anxiety, or physical health status. Future directions include the need for randomized controlled trials and dissemination efforts.

Keywords: PTSD, trauma, severe mental illness (SMI), schizophrenia, exposure therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy

1. Introduction

Despite increased recognition of prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the general population, it is largely ignored among the severely mentally ill (SMI) who are usually treated in public-sector mental health settings. Treatment of prominent psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations, delusions, and bizarre behavior, often take precedence in treating individuals with persistent psychotic disorders, leaving PTSD symptoms unaddressed. There is good cause to believe this is problematic. Sequelae of PTSD typically include increased arousal and distress, social isolation and interpersonal conflict, and generally poor occupational and social functioning. There is evidence of impaired health functioning and increased medical comorbidity from PTSD (Magruder et al., 2004; Schnurr, Spiro, & Paris, 2000). Trauma exposure is associated with higher health care utilization, and PTSD specifically is associated with some of the highest rates of healthcare use, and therefore may be one of the costliest mental disorders (Kessler, 2000; Greenberg et al., 1999). Leaving PTSD unaddressed in the severely mentally ill almost certainly exacerbates patients’ illness severity and hinders their care (Hamner, Frueh, Ulmer, & Arana, 1999; Kimble, 2000; Resnick, Bond, & Mueser, 2003).

Implications are significant because both trauma and PTSD occur at higher rates in adults with SMI than in the general population. Estimates range between 51% and 98% for a single trauma exposure and between 19% and 43% for current PTSD (Cusack et al., 2004; Cusack et al., 2006; Goodman, Rosenberg, Mueser, & Drake, 1997; Mueser et al., 1998; Mueser et al., 2001). For example, in a multi-site study, it was found that 98% of community mental health center patients with SMI had a history of trauma exposure. While a review of standard clinical records indicated that only 2% of the sample carried a diagnosis of PTSD, a thorough research assessment of that sample found the rate of PTSD was 42% (Mueser et al., 1998). Others have reported similar findings (e.g., Cusack et al., 2004; Cusack et al., 2006; Frueh et al., 2002). Thus, PTSD is likely to be a target of intervention in only a small fraction of those SMI patients who might benefit from PTSD-related treatment.

Coinciding with these clinical data is a greater appreciation for the idea that psychotic disorders conceptually are consistent with diathesis-stressor models of mental illness (Corcoran et al., 2003; Mueser, Rosenberg, Goodman, & Trumbetta, 2002; Walker & Diforio, 1997). The premise and evidence indicating that psychosocial stressors play a critical role in the onset and relapse of psychotic episodes in individuals with schizophrenia suggests that ongoing anxiety and trauma related symptoms is likely to precipitate increases in symptoms or relapses in vulnerable individuals (Rosenberg, Lu, Mueser, Jankowski, & Cournos, 2007). Turkington, for example, proposed that the “high levels of arousal arising in posttraumatic stress disorder often maintains and perpetuates psychotic symptoms. In these cases, CBT approaches to posttraumatic stress disorder, including cognitive restructuring and reliving need to be combined with CBT techniques for psychosis (Turkington, 2004, pg. 14).” In fact, there is recent evidence indicating that childhood physical abuse predicts psychosis in adults, and there is a cumulative relationship between trauma and psychotic symptoms, with greater overall number of types of trauma exposure increasing the probability of psychosis (Shevlin, Dorahy, & Adamson, 2007).

This gap in services seems particularly unfortunate, in that there are a number of well established treatments for PTSD. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for PTSD, in particular those interventions that include exposure therapy, has excellent empirical support in randomized control trials (Echeburua, de Corral, Zubizarreta, & Sarasua 1997; Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, 1991; Foa et al., 1999; Tarrier et al., 1999). Exposure therapy for PTSD has also shown promise for adults suffering comorbid drug dependence (Brady, Dansky, Back, Foa, & Carroll, 2001), for adults treated within community clinics (Foa et al., 2005), and for female veterans treated within Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (Schnurr et al., 2007). Data from these and other studies indicate that exposure therapy helps reduce the hallmark features of chronic PTSD (e.g., physiological arousal and maladaptive fear; Foa, 2000; Foa, 2006). In fact, according to the Consensus Statement on PTSD by the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety (Ballenger et al., 2000) and a recent report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2007), the psychotherapy with the strongest empirical support is exposure therapy. Available data do not indicate that exposure has a significant effect on “negative” symptoms of PTSD (e.g., avoidance, impaired social functioning), anger management, or basic social skill deficits (Frueh, Turner, & Beidel, 1995). Thus, it has been suggested that a multi-component program targeting specific areas of dysfunction is necessary to address the complex symptoms associated with this condition (Frueh, Turner, Beidel, Mirabella, & Jones, 1996).

Despite available evidence, there has been little use of exposure therapy or other CBT interventions to treat PTSD by front-line clinicians in “real world” practice settings (Cook, Schnurr, & Foa, 2004). However, there is evidence suggesting that potential patients may prefer exposure therapy among other treatment options (Becker, Darius, & Schaumberg, 2007). Among practice settings that provide services to patients with SMI, and there is virtually no empirical research to support the effectiveness of exposure therapy with this population. In fact, psychotic symptoms or diagnoses have been exclusionary criteria in clinical trials of exposure therapy for PTSD, and there is widespread belief among many clinicians that exposure therapy should not be used with psychotic patients. This may stem from clinician perceptions that CBT in general may not be appropriate or feasible for people with SMI. In a study that evaluated perceptions of clinicians and clinical supervisors from a state-funded mental healthcare system, there were a number of concerns expressed about using exposure-based CBT among those with SMI (Frueh, Cusack, Grubaugh, Sauvageot, & Wells, 2006). One barrier was adequate training. Many clinicians worried that they did not have the necessary skills or experience to address trauma exposure with their clients. Further, they expressed concern that exposure therapy for traumatic reactions would result in severe exacerbation of other symptoms, especially if delivered by itself without other relevant intervention components.

Countering these concerns, however, is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that CBT can be very effective in treating a wide range of symptoms in individuals with SMI, like schizophrenia (Beck & Rector, 2000; Bradshaw, 2000; Dickerson, 2000; Gould, Mueser, Bolton, Mays, & Goff, 2001; Kurtz & Mueser, 2008). Recent reviews and a meta analysis of CBT treatments in schizophrenia (that have in total included over 20 randomized control trials and 1,500 patients) have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT for decreasing many of the symptoms of schizophrenia (Gaudiano, 2005; NICE, 2002; Pilling et al., 2002). There is also sufficient evidence to conclude that CBT is superior to standard care (case management and psychopharmacology) and a range of other therapeutic approaches both at the end of treatment as well as at 12-month follow-up. Importantly, these studies also reported no evidence for symptom exacerbation or clinical deterioration, nor were there any case reports of critical incidents (suicide or self harming behavior) that could be traced to patient involvement in a CBT intervention. In countries outside the U.S., CBT inclusion is increasingly thought to be the standard of care for individuals suffering with schizophrenia (Barrowclough et al., 2006; Turkington, Dudley, Warman, & Beck, 2004; Turkington, Kingdom, & Weiden, 2006).

Despite conceptual and empirical support, there has only been a handful of studies to investigate the value of CBT for PTSD in individuals with SMI. Mueser and colleagues have developed one such program, incorporating components of PTSD education, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, and symptom coping (Mueser, Rosenberg, Jankowski, Hamblen, & Descamps, 2004). A preliminary evaluation of this program found good retention (86%), no adverse clinical outcomes, and reductions in symptom reports on general psychiatric and PTSD specific scales both at completion and 3-month follow-up (Rosenberg, Mueser, Jankowski, Salyers, & Acker, 2004). A concurrently published report by this group on three case studies of individuals with both psychosis and PTSD found that two of the three no longer met criteria for PTSD at the close of the study and all showed modest improvement in other psychiatric symptoms (Hamblen, Jankowski, Rosenberg, & Mueser, 2004).

More recently Mueser et al. (2007) adapted their intervention and evaluated a 21-week “Trauma Recovery Group” that incorporates PTSD education, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, symptom coping, and the establishment of a recovery plan for individuals with SMI. They defined SMI as an Axis I or Axis II disorder with associated functional impairment with respect to the ability to work or care for self. This broad definition of SMI meant that approximately 21% of the sample had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder. Thirty-five percent (35%) were diagnosed with an Axis II disorder, 20% had severe major depression, and 24% had other psychiatric diagnoses. All subjects were outpatients, had a history of trauma, and a diagnosis of PTSD. The authors concluded that the treatment improved PTSD symptoms and diagnosis, depression, and PTSD-related cognitions in those who completed treatment. This research suggests that CBT treatment of trauma may have few adverse effects and provide significant benefits for those with PTSD and SMI, although it does not provide information in the use of exposure-based therapy for this population. These findings were recently extended and supported in a large randomized clinical trial of 108 patients with PTSD and SMI (Mueser et al., 2008).

This paper reports on the development and preliminary evaluation of a multi-component cognitive-behavioral intervention, incorporating exposure therapy, to reduce PTSD symptoms in adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. By definition, our target population (i.e., patients with dual diagnoses of schizophrenia and PTSD) has a far more complex symptom picture than individuals with PTSD alone. The positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia complicate efforts to provide cognitive-behavioral interventions for comorbid disorders, such as PTSD. Components of our intervention in this pilot study were derived, developed, and adapted based on literature reviews, multi-component intervention models for other psychiatric populations (Turner et al., 1994), our own clinical experiences with this population, and a qualitative research study (Frueh et al., 2006) to learn about the perspectives and suggestions of clinicians and supervisors in the community mental health system working with these patients. This work stands alone in that it is the only study to use exposure for PTSD in a sample that consisted of individuals with primary psychotic diagnoses.

2. Method

2.1. Overview of Study Design

This study was an open trial evaluation of a multi-component cognitive-behavioral intervention to reduce PTSD symptoms in 20 adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder served within a public-sector community mental health system. The intervention consisted of psycho-education, anxiety management therapy, social skills training, and exposure therapy. Participants engaged in 22 sessions of a group and individually administered CBT that occurred over an 11-week period, and provided within the context of their treatment as usual care.

2.2. Setting

Participants were recruited into the study from two programs affiliated with a Community Mental Health Center (CMHC) in a medium sized Southeastern city. The first was a psychosocial rehabilitation day-treatment program focused on community-based case-management and rehabilitative services. Many of the patients had multiple psychiatric hospitalizations and required assistance with general social skills, independent living skills, symptom management, pre-vocational skills, and psychopharmacological management of psychiatric symptoms. The second program was an outpatient clinic providing case-management, therapy, psychiatric assessment and medication to individuals with SMI.

2.3. Participants

To meet study inclusion/exclusion criteria for participation patients must have: 1) been receiving mental health care through the one of two CMHC-affiliated programs, with at least biweekly contacts with a case-manager; 2) been at least 18 years old; 3) met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD (as determined by the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale); 4) met criteria for our study definition of SMI, defined as a mental illness resulting in persistent impairment in self-care, work, or social relationships, plus a past year history of DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; 5) not met DSM-IV criteria for current alcohol or drug dependence; 6) not had a history of psychiatric hospitalization or suicide attempt in the previous 2 months; and 7) been able to provide informed consent to participate in the research study. These criteria were chosen to ensure that our intervention, designed to be provided within the context of comprehensive treatment for SMI, was able to focus primarily on symptoms and impairments related to PTSD and yet would generalize to a substantial percentage of the population with PTSD and SMI. Demographic and baseline information on study participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline Demographics and Outcomes.

| Total Sample (n = 20) | Completer (n = 13) | Non-Completer (n = 7) | χ2 or Fisher’s Exact Test* | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 25% (5) | 7.69 (1) | 57.14 (4) | ||

| Female | 75% (15) | 92.31 (12) | 42.86 (3) | 5.93 | .03 |

| Relationship Status | |||||

| Alone | 85% (17) | 84.62 (11) | 85.71 (6) | .004 | |

| With Other/Spouse | 15% (3) | 15.38 (2) | 14.29 (1) | .95 | |

| Employment | |||||

| Not Working | 90% (18) | 100% (13) | 71.43 (5) | .11 | |

| Part-time | 10% (2) | 0.00 | 28.57 (2) | 4.13 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 5% (1) | 7.69 (1) | 0.00 | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 95% (19) | 92.31 (12) | 100 % (7) | .57 | 1.00 |

| Race | |||||

| Minority | 40% (8) | 46.2% (6) | 28.6% (2) | ||

| Non-Minorit | 60% (12) | 53.8% (7) | 71.4% (5) | .59 | .64 |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | t-value (df) | p-value | |

| Age | 42.30 (8.40) | 41.15 (9.41) | 44.43 (6.19) | -.82 (18) | .42 |

| Education | 12.50 (2.41) | 11.92 (2.02) | 13.67 (2.88) | -1.51 (16) | .15 |

| Clinical & Process Outcomes | |||||

| PTSD | |||||

| CAPS Total | 67.30 (17.23) | 65.08 (19.25) | 71.43 (12.97) | -.78 (18) | .45 |

| PCL | 58.30 (12.11) | 56.00 (13.62) | 62.57 (7.81) | -1.17 (18) | .26 |

| Other Psychiatric Difficulties | |||||

| SF-36 Total | |||||

| SF-36 Physical Health | 46.21 (14.98) | 43.89 (10.40) | .36 (16) | .73 | |

| SF-36 Mental Health | 32.94 (13.18) | 29.07 (10.15) | .66 (16) | .52 | |

| HAM-A | 18.05 (8.73) | 17.39 (9.92) | 19.29 (6.45) | -.45 (18) | .65 |

| HAM-D | 25.00 (12.44) | 24.39 (13.63) | 26.14 (10.79) | -.29 (18) | .77 |

| NAI (Anger) | 91.05 (21.87) | 99.85 (18.46) | 74.71 (18.80) | 2.89 (18) | .01 |

| CGI | 2.85 (1.14) | 3.92 (1.12) | 3.71 (1.25) | .38 (18) | .71 |

| Treatment Satisfaction & Credibility | |||||

| Satisfaction (CPOSS) | 38.79 (7.61) | 38.08 (7.92) | 40.33 (7.34) | -.59 (17) | .56 |

| Credibility | 30.29 (9.15) | 30.00 (9.57) | 31.25 (8.85) | -.23 (15) | .82 |

Note: Comparisons between completer and non-completer groups; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PCL = PTSD Checklist; SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; HAM-A = Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HAM-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; NAI = Novaco Anger Inventory; CGI = Clinical Global Impressions Scale; CPOSS = Charleston Psychiatric Outpatient Satisfaction Scale.

2.4. Measures

The following measures were used to screen potential participants for eligibility:

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview

(MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998). The MINI is an abbreviated structured psychiatric interview that takes approximately 15-20 minutes to complete. It uses decision tree logic to assess the major adult Axis I disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10. It elicits all the symptoms listed in the symptom criteria for DSM-IV and ICD-10 for 15 major Axis I categories, and one Axis II disorder. It has been demonstrated to have good psychometric properties in the evaluation of persons with serious mental illness. The MINI was used to screen out substance dependence.

Trauma Assessment for Adults—Interview Version

(TAA; Resnick, Best, Kilpatrick, Freedy, & Falsetti, 1993). This 17-item instrument assesses for a range of lifetime history of PTSD’s criterion A1 traumatic events from natural disasters and serious accidents to interpersonal violence such as physical and sexual assault. Age of first and most recent occurrence is determined for multiple incidents of a given type and follow-up questions are included to assess perceived life threat. This instrument has been demonstrated to have strong psychometric properties and has been widely used in research on trauma exposure in adults (Resnick, 1996). Furthermore, recent data show that trauma histories can be reliably assessed among public sector patients with SMI (Goodman et al., 1999; Mueser et al., 2001).

Clinician—Administered PTSD Scale

(CAPS; Blake et al., 1990; Weathers & Litz, 1994; Weathers et al., 1999). The CAPS is a 17-item structured interview that assesses both frequency and intensity of PTSD symptoms according to DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria. It provides both a dichotomous index for PTSD diagnoses and a continuous index of PTSD symptom severity. The scale has been shown to have robust psychometric properties, including strong interrater reliability (.92 to .99), high internal consistency (.73 to .85), and high convergent validity (Weathers & Litz, 1994; Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). Recent data show that PTSD diagnoses can be reliably assessed among public sector patients with SMI (Goodman et al., 1999; Mueser et al., 2001). PTSD symptoms were assessed with the CAPS for up to three distinct traumatic events. In the case of multiple instances of the same event (e.g., repeated sexual abuse in childhood) subjects were asked to consider these as one event. Post-treatment and follow-up administrations of the CAPS focused on the same event(s) that were the basis for the pre-treatment CAPS ratings (and the focus of treatment sessions).

Subjects also completed a battery of instruments at pre-, post, and 3-month follow-up in order to evaluate treatment outcome. The CAPS, which was the primary outcome measure, was included with the outcome measures listed below. All of the interviews and clinician rating scales were audiotaped and a second evaluator rated 25% independently in order to determine inter-rater agreement (Kappa = 1.00).

2.4.1. PTSD

PTSD Checklist

(PCL; Weathers et al., 1993). The PCL is a 17-item self-report measure of PTSD symptoms based on DSM-IV criteria, with a 5-point Likert scale format. It is highly correlated with the CAPS (r = .93), has good diagnostic efficiency (> .70), and has robust psychometric properties with a variety of trauma populations, including SMI (Grubaugh, Elhai, Cusack, Wells, & Frueh, 2007; Magruder et al., 2002). Scores on the PCL range from 17-85, with a score of 50 or higher indicating probable PTSD among those presenting for mental healthcare. This measure was administered at each assessment point, as well as at each treatment session.

2.4.2. Other Psychiatric Difficulties

Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety

(HAM-A; Hamilton, 1959). This well known clinical rating scale was used to assess general level of anxiety.

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

(HAM-D; Hamilton, 1959). The HAMD was used as a measure of depression.

Clinical Global Impressions Scale

(CGI; Guy, 1976). The Severity and Global Improvement Subscales are each 7-point scales, which are part of the ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. They were used to assess overall symptom severity and improvement.

2.4.3. Role Functioning

Novaco Anger Inventory

(NAI; Novaco, 1975). The NAI is a widely used anger measure that was developed to measure the degree of provocation or anger people would feel if placed in various situations. We used the short form version, adapted from the original version, which contains 25 of the original 90 items. This scale displays a convergent validity of .46 with the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory, and .41 with the Aggression subscale of the Personality Research Form (Huss, Leak & Davis, 1993) as well as test-retest reliabilities between .78 and .91 (Mills, Kroner & Forth, 1998).

Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey

(SF-36; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). The SF-36 is a widely used, self-report measure of functional status that assesses two factor-analytically derived dimensions: physical health (physical functioning, role functioning limited by health, energy and fatigue, pain, general health, and health change); and mental health (role functioning limited by emotional problems, emotional well-being, and social functioning). This measure has recently been shown to be associated with severity of PTSD symptoms (Magruder, Frueh et al., 2002) and to be sensitive to change in response to treatment for PTSD symptoms (Malik et al., 1999).

Objective Functional Indicators

Data were collected via a clinician-administered rating form regarding objective indicators of social functioning, such as changes in marital status, employment status, residential status, legal involvement, hospitalizations, and primary care visits.

2.4.4. Treatment Satisfaction and Credibility

Charleston Psychiatric Outpatient Satisfaction Scale

(CPOSS; Pellegrin et al., 2001). The CPOSS is 16-item measure with a Likert scale response format. It was used to assess patients’ perceptions regarding the overall care they received by both the CBT program investigators and each patients respective CMHC program site. This measure was previously used with adults with chronic PTSD and SMI (Frueh et al., 2002). Participants completed this measure after the third week of treatment and again at post-treatment.

Treatment Credibility

To assess treatment credibility, treatment expectancy scales developed by Borkovec and Nau (1972) were used. Four of the questions were used for this study. These include 1) how logical the treatment appears, 2) how confident participants are about the treatment, 3) their expectancy of success, and 4) how successful the treatment would be in decreasing another fear. Participants completed these 10-point rating scales after the third week of treatment and again at post-treatment.

2.5. Therapist Adherence and Competence

In order to ensure that treatment was competently administered in accordance with the manual, all sessions were audiotaped, and 20% of these were rated for competence and adherence by master’s level or above clinicians. Two raters evaluated the tapes independently to allow for computation of inter-rater reliability. To evaluate adherence, rating forms were developed based upon the treatment manual to determine if the therapist appropriately covered the content of each session (i.e., demonstrated the particular behavior described in each item). To evaluate competence, rating forms were developed to assess how well the therapists accomplished a range of relevant tasks for each session (i.e., how well they carried out the particular behaviors described in each item). These rating forms used 7-point Likert scale response formats, and were modeled after therapist adherence/competence forms successfully used in other similar cognitive behavioral treatment interventions (Frueh et al., 2007). Computation of inter-rater reliability on adherence items (“yes”/“no”) revealed moderate to perfect agreement across items measured (i.e., kappa’s ranged from .71 to 1.00). Competence ratings ranged from “good” to “very good,” with the average rating across the primary and secondary raters being 6.20 and 6.07, respectively.

2.6. Procedures

Participants were recruited into the study through case managers at one of the CMHC-affiliated programs. The research team made a series of presentations to the clinical staff regarding the CBT treatment study and the eligibility criteria. CMHC clinicians then approached potentially eligible patients (i.e., patients identified as having trauma histories and probable PTSD) to inform them of the study and notified the research team when a patient expressed an interest. The research team also contacted clinicians periodically to inquire about any referrals to the study. Project staff then confirmed that referred patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in their CMHC chart. Once potential participants were identified, a member of the research team met with each patient to explain the study, answer questions, and obtain informed consent. Following consent, participants were screened for eligibility using the Objective Functional Indicators, TAA, MINI, and CAPS.

Therapists in the study were four doctoral-level clinical psychologists and one masters-level clinician with previous training in CBT and experience treating individuals with PTSD. All therapists were trained in the specific multi-component CBT manual. Therapists met weekly during the treatment phase of the study to discuss progress and any problems with the treatment. In addition, a member of the research team attended weekly team meetings at the CMHC sites in order to review progress, changes, problems and symptom status of study participants.

2.7. The Intervention

We developed and manualized a multi-component cognitive-behavioral intervention specifically for this population. Based on a multi-component intervention for social phobia (Turner et al., 1994) and PTSD among combat veterans (Frueh et al., 1996; Turner, Frueh, & Beidel, 2005), and guided by research with community mental health center clinicians (Frueh et al., 2006) the intervention consisted of: 1 session of psycho-education, 2 sessions of anxiety management, 7 sessions of social skills and anger management training, 4 sessions of trauma issues management, 8 sessions of exposure therapy, and homework activities. The first four components were conducted via group therapy format, which were held twice-weekly. Following completion of group components, participants had 8 individual therapy sessions also held twice weekly. All treatment sessions included homework assignments related to the session module content (e.g., breathing exercise during anxiety management; instruction to listen to audiotaped recording of trauma narrative from exposure sessions). The intervention was completed over an 11-week period and was provided within the context of the patients’ usual care. All patients continued with their regular course of treatment, including individual case-management sessions and psychiatric medications, which were not altered for study participation. Each of the treatment components is described below. For a more in-depth description of the development and elements of CBT for PTSD among adults with SMI see treatment manual available from the lead author (Frueh et al., 2007).

2.7.1. Education

During this session participants were provided with a general overview of chronic PTSD, including common patterns of expression, comorbidity of other anxiety and Axis I disorders, impact on social functioning, and a review of current treatment strategies. This phase was important for ensuring that participants developed a realistic understanding of their symptoms and prognosis, as well as an overall positive expectancy regarding the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral interventions. Further, this phase was used to educate participants about the specific treatment they would receive and what would be expected from them regarding their participation in the treatment program.

2.7.2. Anxiety Management Skills Training

During this component, participants were taught skills to better manage their anxiety and stress levels, including the control of panic attacks. This structured anxiety management skills training program was targeted towards both specific and general anxiety symptoms that trauma survivors often experience and included elements of relaxation training, breathing retraining, and panic control.

2.7.3. Social Skills and Anger Management Training

The purpose of this module was to teach patients the requisite skill foundation for effective and rewarding social interactions. While trauma survivors with SMI may vary with respect to basic social skills, most have vast room for improvement. A structured social skills training program was targeted towards the cluster of symptoms that do not appear to be helped by mere exposure alone. In other words, interpersonal difficulties commonly associated with chronic PTSD, such as social anxiety, social alienation and withdrawal, excessive anger and hostility, explosive episodes, and family conflict were targeted. Social skills training included instruction, modeling, behavioral rehearsal, feedback, and reinforcement. Following each session, participants were given homework assignments to allow further practice and consolidation of newly acquired skills.

2.7.4. Trauma Issues Management

As a specialized aspect of social skills training, the goal of this module is to improve communication regarding past traumas with others, so as to increase the understanding of family and significant others where appropriate and assume greater control of disclosure and environmental cues. Participants are taught how to assertively communicate when they are unwilling to talk to others about trauma-related issues or events. In addition, they are also taught to identify and challenge negative and dichotomous thinking patterns (e.g., mistrust of others), which limit their quality of life by reducing their activities and involvement with others. Finally, this component includes sessions on safety planning, a necessary component because data show that many trauma victims are at increased risk for re-victimization.

2.7.5. Exposure Therapy

Exposure therapy was administered in eight individual therapy sessions. After reminding participants of the rationale for exposure therapy, the patient and therapist worked collaboratively to construct the imaginal exposure narrative. Imaginal exposure sessions lasted approximately 60 to 90 minutes depending on the needs and abilities of the patient. Exposure narratives were audiotaped for use as homework assignments throughout the week. All exposure sessions ended with a discussion of the experience for the patient, including difficulties encountered with the process and concerns the patient had regarding the exercise. Additionally, patients were given the option of participating in a guided relaxation exercise prior to leaving the session. Exposure was placed last in the sequence of intervention components because community mental health center clinicians suggested in focus groups (Frueh et al., 2006) that other study components would be necessary to help these vulnerable patients develop trust and rapport with therapists, as well as a sense of mastery, to support their engagement with exposure therapy.

2.8. Planned Statistical Analyses

2.8.1. Preliminary descriptive analyses

Univariate descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and frequency distributions for categorical variables, including proportion meeting criteria for specific traumas (TAA) and psychiatric diagnoses (MINI)) were used to describe demographic and baseline clinical variables for the total sample (n = 20), those who completed the study (n = 13), and those who dropped out (n = 7). See Table 1. These descriptive analyses also allowed evaluation of distributional assumptions underlying proposed statistical tests. Continuous demographic (i.e., age, income), baseline clinical (i.e., CAPS, PCL, SF-36, Ham-A, Ham-D, NAI, CGI), and baseline satisfaction and credibility scores were compared for the group that completed the study and the group that dropped out using an independent sample t-test. Categorical demographic variables (i.e., gender, relationship status, employment, ethnicity, race) were compared for the completer versus non-completers using chi-square or Fisher’s Exact Test.

2.8.2. Analysis sets

First, analyses were carried out using only subjects (n = 13) who competed the treatment (i.e., at least 70% of sessions) (Analysis set 1). Analyses were carried out separately for the pre- to immediately post-treatment period (pre-post), the pre- to 3-month post active treatment (pre- to 3-month), and immediately post- to 3-month post active treatment (post- to 3-month). This strategy was chosen to address the a priori hypotheses that the intervention would result in “short term” (pre-post) improvement; this improvement would be “sustained” for 3 months after the end of the active treatment phase (pre- to 3-month); and that there would be additional, but modest, improvement following the end of active treatment (post- to 3-month).

Analyses were then repeated using observed data (all available data at each time point) to evaluate the effect in this group (Analysis set 2). Finally, analyses were carried out using the sample comprising all subjects who had at least one post-baseline measurement (Analysis set 3). For this analysis set, missing end-of-active treatment (post-scores) and 3-month scores were imputed using a multiple imputation method (Little & Rubin, 1987). Because results (effect sizes and p-values) were similar in almost all cases for the three analysis sets, we present only the data for Analysis set 1. Instances where results differed qualitatively (i.e. with respect to statistical significance of a comparison) will be noted in the text.

It should be noted that the purpose of this pilot study was to obtain preliminary indication of a clinical “signal” of the effectiveness of exposure-based cognitive behavioral treatment of PTSD in adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, rather than to definitively confirm hypotheses regarding the intervention’s efficacy. Accordingly, in recognition that a false positive (Type I) error is of usually less concern in an exploratory pilot study than a false negative (Type II error), no adjustment for multiple outcomes or multiple analyses was used to maintain a stringent Type I error rate.

2.8.3. Efficacy Analyses

The primary PTSD efficacy outcome was the change in continuous CAPS score measured at baseline (pre-), immediately post-treatment, and at 3-months post treatment. A secondary PTSD efficacy outcome was the PCL measured after each treatment session. Additional secondary efficacy outcomes included the SF-36, HAM-A, HAM-D, NAI, and CGI, social functioning indices, and number of primary care visits. Paired t-tests and Wilcoxon signed ranks test were used to evaluate the statistical significance of change scores (pre-post, pre-3-month, post-3-month). Results from paired t-tests are presented unless distributional assumptions were violated and results differed by test used. Additionally, for the PCL, the slope of the trajectory for the collection of longitudinal measurements was evaluated using a repeated measures, mixed models approach (SAS Proc Mixed; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Clinical effect sizes are described via 95% confidence intervals for means.

3. Results

Sixty-one patients were referred to the study. Of these, 33 were ineligible, 6 declined to participate, 1 was administratively removed from the SCDMH day program, and one was unreachable after the initial contact. One patient was expelled from her day-treatment program for potential criminal behavior. Thus, we recruited 20 patients who met inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study and form our intent-to-treat sample. Based on chart review, every participant had a diagnosis of either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. On structured clinical psychiatric interviews (i.e., CAPS and MINI) all of our sample met criteria for PTSD and a psychotic disorder, 70% met criteria for current depression, 20% for bipolar disorder, 65% for panic disorder, 30% for agoraphobia, 25% for social phobia, 15% for obsessive compulsive disorder, and 20% for generalized anxiety disorder. Lifetime trauma exposure from the TAA revealed that 45% of the sample reported a serious accident, 60% reported child sexual abuse (CSA) before the age of 13, 55% reported CSA before the age of 18, 50% reported a sexual assault in adulthood, 45% reported a physical assault with a weapon, and 70% reported a physical assault without a weapon. Most patients had experienced multiple traumatic events across categories.

Of the 20 participants who started treatment, 13 completed treatment (i.e., at least 70% of sessions) for a completion rate of 65%. With one exception, there were no statistically significant differences between completers and non-completers (see Table 1). The one exception was gender: completers were more likely to be female than male, 92.3% versus 7.7%, χ2 = 5.93, p = .03. However, this gender difference, may also represent a site effect in that all males in the study were recruited at one clinical program. A site effect may be due to the fact that those participating in a more intensive day-hospital program, with a regular schedule and coordinated transportation, are more likely to complete treatment than those in a more traditional outpatient program. With the exception of NAI scores, there were no statistically significant differences between completers and non-completers on clinical outcomes, treatment satisfaction, or treatment credibility scores. Treatment completers had higher (i.e., more severe) anger scores at pre-treatment than those who dropped out.

Using all patients enrolled for the trial (n = 20), there were no statistically significant differences in average session attendance or average homework compliance by initial CAPS total scores, initial treatment expectancy total scores, race, or gender. There were also no statistically significant differences between any of the individual treatment expectancy items by gender or race. Average number of sessions attended among those who dropped out of treatment was 7.86 (sd = 5.52; range 1-15 sessions).

Using all patients enrolled in the trial, there were no statistically significant gender or race differences on the treatment expectancy total score or any of the individual items. Total treatment expectancy scores ranged from 4 to 40 (m = 30.29, sd = 9.15) and the individual items ranged from 1 to 10 [mean (sd) for item 1 = 8.00 (2.52), mean (sd) for item 2 = 6.83 (2.88), mean (sd) for item 3 = 8.44 (2.43), and mean for item 4 = 7.28 (2.72)]. Twenty percent (n = 4) stated that they would “definitely” recommend the program to a friend or family member and 80% (n = 16) stated they would “probably” recommend the program to a friend or family member, with no statistically significant differences between completers and non-completers on this item, 3.85 (sd = .38) versus 3.71 (sd = .18). t = .68, p = .51.

Of those patients who completed the treatment (n = 13), none (0%) had a job change from pre-assessment to any of the post-assessments, none (0%) had a change in his/her marital status, 4 (30.8%) were hospitalized on a psychiatric unit, 4 (30.8%) were hospitalized on a medical unit, 0 (0%) were arrested for legal difficulties, and 5 (38.5%) changed their place of residence.

3.1. Efficacy Analyses

In the first analysis set (i.e., n = 13; those who completed the treatment), CAPS total, CAPS cluster D, PCL, NAI, and CPOSS satisfaction change scores were significantly improved from pre- to post-treatment (Table 2). From pre- to 3-months, CAPS total, CAPS B, C, and D cluster, PCL, NAI, SF-36 mental health, and CPOSS satisfaction change scores were significantly improved. From post- to 3-months, CAPS B cluster and SF-36 mental health change scores were significantly improved. Average patient self-ratings of treatment improvement in this group were 4.23 (sd = .60) (“a little better”) at post-treatment and 3.85 (sd = .90) (between “no change” and “a little better”) at 3-months. There was a statistically significant difference from pre to post-treatment in patients’ self report of the quality of their social relationships, with improved scores at post-treatment. Patients also endorsed fewer primary care visits from the pre-assessment to 3 months. Results from Analysis sets 2 and 3 were quite similar to those for Analysis set 1.

Table 2. Estimated Mean Clinical and Process Outcomes Change at Pre-Treatment, Post-Treatment and Three-Month Follow-Up (Treatment Com pleters Only, n=13).

|

Outcome Variable |

Pre to Post Change |

SE | 95% CL | t- value |

p | Pre to 3 Month Change |

SE | 95% CL | t- value |

p | Post to 3 Month Change |

SE | 95% CL | t-value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD | |||||||||||||||

| CAPS Total | 20.46 | 8.16 | 2.68, 38.24 | 2.51 | .03 | 30.62 | 7.85 | 13.52,47.71 | 3.90 | .00 | 10.15 | 4.81 | -.32,20.63 | 2.11 | .06 |

| CAPS B | 7.46 | 3.80 | -.82,15.74 | 1.96 | .07 | 11.54 | 4.02 | 2.77,20.30 | 2.87 | .01 | 4.08 | 1.78 | .20,7.96 | 2.29 | .04 |

| CAPS C | 8.62 | 4.29 | -.73,17.96 | 2.01 | .07 | 11.77 | 3.14 | 4.92,18.62 | 3.74 | .00 | 3.15 | 3.00 | -3.38,9.69 | 1.05 | .31 |

| CAPS D | 4.54 | 1.66 | .92,8.15 | 2.74 | .02 | 7.31 | 1.95 | 3.06,11.55 | 3.75 | .00 | 2.77 | 1.62 | -.76,6.30 | 1.71 | .11 |

| PCL | 13.92 | 5.50 | 1.93,25.91 | 2.53 | .03 | 18.77 | 5.14 | 7.56,29.98 | 3.65 | .00 | 4.85 | 5.57 | -7.29,16.98 | .87 | .40 |

| Other Psychiatric Difficulties | |||||||||||||||

| HAM-A | 1.82 | 4.06 | -7.24,10.88 | .45 | .66 | 2.38 | 3.29 | -4.78,9.55 | .73 | .48 | -.91 | 2.42 | -6.30,4.48 | -.38 | .72 |

| HAM-D | 2.64 | 4.95 | -8.40,13.67 | .53 | .61 | 4.38 | 3.88 | -4.06,12.83 | 1.13 | .28 | -.27 | 2.58 | -6.02,5.48 | -.11 | .92 |

| CGI | .09 | .48 | -.97,1.15 | .19 | .85 | -.15 | .37 | -.97,.66 | -.41 | .69 | -.36 | .24 | -.91,.18 | -1.49 | .17 |

| Role Functioning | |||||||||||||||

| Anger (NAI) | 16.23 | 3.27 | 9.10,23.36 | 4.96 | .00 | 28.08 | 6.34 | 14.25,41.90 | 4.43 | .00 | 11.85 | 7.24 | -3.93,27.62 | 1.64 | .13 |

| SF-36 Total | |||||||||||||||

| SF-36 Physical Health | -3.02 | 2.38 | -8.33,2.29 | -1.27 | .23 | 4.25 | 2.64 | -1.83,10.34 | 1.61 | .15 | 4.99 | 3.47 | -3.00,12.99 | 1.44 | .19 |

| FS-36 Mental Health | -.51 | 3.60 | -8.52,7.51 | -.14 | .89 | -11.64 | 2.29 | -16.92,-6.37 | -5.09 | .00 | -9.65 | 3.75 | -18.30,-1.00 | -2.57 | .03 |

| Number of social activities in home | -4.08 | 2.80 | -10.18,2.02 | -1.46 | .17 | -.54 | 3.01 | -7.11,6.03 | -.18 | .86 | 3.54 | 4.18 | -5.56,12.64 | .85 | .41 |

| Number of social activities outside home | -3.15 | 2.12 | -7.77,1.46 | -1.49 | .16 | -3.46 | 2.56 | -9.03,2.11 | -1.35 | .20 | -.31 | 3.09 | -7.05,6.43 | -.10 | .92 |

| Quality of Social Relationships | -1.31 | .58 | -2.57,-.04 | -2.25 | .04 | -.77 | .94 | -2.82,1.28 | -.82 | .43 | .54 | .64 | -.85,1.93 | .85 | .41 |

| Service Use | |||||||||||||||

| # of Psychiatric Hospitalizations | -.23 | .23 | -.73,.27 | -1.00 | .34 | -.23 | .20 | -.67,.21 | -1.15 | .27 | .00 | .25 | -.55,.55 | .00 | 1.00 |

| # of Medical Hospitalizations | .08 | .26 | -.50,.65 | .29 | .78 | .23 | .12 | -.03,.50 | 1.90 | .08 | .15 | .19 | -.26,.57 | .81 | .44 |

| # of Primary Care Visits | -.69 | 1.85 | -4.72,3.33 | -.38 | .71 | 2.08 | .87 | .19,3.96 | 2.40 | .03 | 2.77 | 2.15 | -1.91,7.44 | 1.29 | .22 |

Note: PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PCL = PTSD Checklist; HAM-A = Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HAM-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; CGI = Clinical Glo bal Impressions Scale; NAI = Novaco Anger Inventory; SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

Despite the illness burden of this small sample, preliminary findings from this project indicate that the treatment is efficacious. At 3-month follow-up 10 of 13 patients no longer met criteria for PTSD, and 10 of 13 were considered treatment responders, with at least a 15-point decrease in CAPS scores. These two methods for interpreting progress are important to consider together since even incremental decreases in CAPS scores can at times result in a lost diagnosis due to the symptom cluster scoring criteria. When taken together, however, it is worth noting that only one patient failed to either lose his/her diagnosis and/or not meet criteria for a treatment responder. In combination, these data suggest that individuals with SMI and PTSD are able to tolerate exposure based interventions, and most importantly, can benefit from them.

Although the sample size for minority patients (n = 6 completers) was typically too small to yield statistically significant changes, there were significant CAPS total (change score = 27.00, std error = 9.89, t = 2.73, p = .04), CAPS cluster C (change score = 10.33, std error = 3.32, t = 3.11, p = .03), PCL (change score = 15.83, std error = 3.76, t = 4.21, p = .01), NAI (change score = 21.83, std error = 3.44, t = 6.35, p = .00), and SF-36 mental health (change score = -11.68, std error = 2.02, t = -5.78, p = .01) change scores from pre- to 3-months. There were also statistically significant NAI change scores in this group from pre- to post (change score = 21.67, std error = 4.96, t = 4.36, p = .01) and SF-36 mental health change scores from post to 3-months (change score = -9.43, std error = 1.56, t = -6.05, p = .01). The majority of the other outcomes demonstrated a strong trend in the anticipated direction.

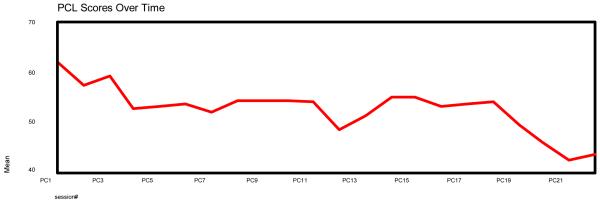

With regard to PCL scores collected at every session, we conducted paired t-tests from session 1 to session 14 (beginning of treatment to end of the group component), from Session 1 to session 22 (beginning of treatment to end of treatment), and from session 15 to session 22 (beginning of exposure component to end of treatment). Paired t-tests revealed significant PCL symptom improvement from session 1 to session 22, t = 3.32(12), p = .006, from session 15 to session 22, t = 2.28(12), p = .042, but not from session 1 to session 14, t = 1.71(12), p = .114. Consistent with the downward trend of PCL means over time as shown in Figure 1, the longitudinal trajectory of individual PCL change scores across 22 sessions of the intervention indicates a significant improvement over time as suggested by a statistically significant negative slope (time coefficient = -0.50, p = 0.0400, SAS Proc Mixed). Taken together, these data suggest that the most significant patient gains were made at the onset of the treatment (during the education and relaxation components; sessions 1 through 4) and from the latter part of the treatment program (during the latter stages of the exposure component).

Figure 1. Posttraumatic Stress Checklist (PCL) Observed Scores for Completers (n = 13) by Session.

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical and Process Outcomes

Results of this open trial of manualized exposure-based cognitive-behavioral therapy offer preliminary optimism for the effective treatment of PTSD among adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, high psychiatric comorbidity, and meeting criteria for SMI. Both clinical and process outcomes are encouraging, especially among treatment completers. Clinical outcome efficacy for PTSD at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up is extremely promising. Clinical interview data (total CAPS) for completers showed significant symptom reductions, with mean 20 (pre- to post-treatment) and 30 (pre- to 3-month follow-up) point reductions, with similar patterns of symptom improvement for each of the three PTSD symptom clusters. Further, at 3-month follow-up 10 of 13 completers no longer met criteria for PTSD, 10 of 13 were considered treatment responders, and 12 of 13 either no longer met criteria for PTSD or were considered treatment responders. Self-report data (PCL) provide additional evidence of PTSD symptom improvement after the initiation of treatment. The clinical outcome for other relevant domains is also encouraging. For example, anger (NAI), general mental health (SF-36, mental health subscale), and ratings of perceived quality of social relationships all improved at post-treatment and/or 3-month follow-up. These were all areas specifically targeted by the CBT intervention.

Unfortunately, significant improvements were not noted in depressive symptoms (HAM-D), general anxiety symptoms (HAM-A), frequency of self-reported social activities, or physical health status (SF-36). Furthermore, we did not evaluate psychotic symptoms in this study so cannot comment on this important symptom domain.

Process outcomes associated with the CBT intervention are promising and no adverse events were observed for any participant. Participants reported high levels of treatment credibility and satisfaction with care, and completers showed strong session attendance and homework compliance. Unfortunately, high drop-out (i.e., 35%), often found in clinical studies of trauma survivors and SMI populations, means that many enrolled participants did not benefit from the intervention. Conversely, however, patients who remained in the treatment tended to benefit from it and were satisfied with the treatment they received.

4.2. Feasibility of Treatment Implementation

Data also support feasibility of treatment implementation. There were no adverse effects associated with any aspect of the intervention, including the exposure therapy component. In fact, no participants dropped out during exposure therapy. Further, no participants’ clinical status deteriorated significantly during the course of the study. We also established evidence of strong therapist adherence and competence in following the manualized cognitive-behavioral program, suggesting that it can be used with fidelity in practice settings. In combination with clinical and process outcomes, these findings provide hope that effective psychosocial interventions for PTSD can be incorporated into current efforts (Cusack, Wells, Grubaugh, Hiers, & Frueh, 2007; Frueh, Cusack et al., 2001; Rosenberg et al., 2001) to improve mental health services for adults with SMI treated in public sector clinics.

4.3. Study Strengths

This study has several important and novel aspects to it. First, the outcome results show extremely promising outcomes at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up across a range of PTSD clinical and process variables in a sample of severely mentally ill adults with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, high levels of psychiatric comorbidity, and impaired functioning. This is a group almost completely excluded from clinical research with and clinical services for PTSD. Second, to our knowledge this is the first study to apply exposure therapy for PTSD, a well-established evidence-based practice, with schizophrenia-spectrum disorder patients. Third, the sample is heavily minority (6 of 13 completers), and analyses support the clinical efficacy and acceptability of the intervention in the racial minority sub-sample. Fourth, component efficacy for exposure therapy and other elements of the intervention is supported via session-level data collected on PTSD symptoms (see Figure 1).

4.4. Study Limitations

Despite its merits this study has important methodological limitations. This is an open-trial, with a relatively small sample and low power, allowing for potential Type I error and limiting conclusions related to causality of the intervention. Further, due to this design, clinical interviewers were not blind to study condition, although this concern is mitigated somewhat by the strong interrater agreement noted in a random sample of interviews (Kappa = 1.00 for PTSD) and inclusion of patients self-report measures. In fact, results from clinical interviews of PTSD symptoms (e.g., CAPS) match quite well with results obtained from self-reported PTSD symptoms (e.g., PCL). Finally, the drop-out rate (35%) is rather high for a treatment outcome study. Unfortunately, this drop-out rate is likely a reflection of the impaired role-functioning and chaos that characterizes the life of these adults with SMI, and this attrition rate is comparable to that of another study that found a 41% drop-out rate in the treatment of PTSD among adults with SMI (Mueser et al., 2007). Comparison of completers and non-completers in this study suggests that the two groups were not significantly different from each other at baseline on demographic, comorbidity, or illness severity; the primary variable of difference was setting—those participating in a more intensive (i.e., daily) day-hospital program, with a regular schedule and coordinated transportation, were more likely to complete treatment than those in a more traditional outpatient program.

4.5. Future Directions

While preliminary findings are extremely promising, additional research is needed. Future studies should include larger samples, with other diagnoses associated with SMI (e.g., bipolar disorder), and hypotheses-driven randomized methodology, including efficacy and effectiveness designs. These studies should examine outcomes on a broad array of relevant variables, including depression and psychotic symptoms. For example, does reducing PTSD severity reduce psychotic symptoms and improve role functioning? How can depressive symptoms be addressed more effectively? Efforts to simplify or shorten the 22-session intervention might also be useful. Dismantling studies may further support the trend suggested in Figure 1 that some of the social skills training sessions may not be as clinically important as the psychoeducation and exposure therapy components, though improvements in anger and quality of social relationships noted in this sample may support inclusion. It might be useful to evaluate the effectiveness of exposure therapy only. Also needed is further study of strategies to reduce drop-out and improve session attendance (e.g., contingency management, facilitation of transportation, implementing interventions in day-hospital settings; Lefforge, Donohue, & Strada, 2007). Finally, efforts will be needed to disseminate efficacious treatments for PTSD in this population (Cahill, Foa, Hembree, Marshall, & Nacash, 2006; Cook, Schnurr, & Foa, 2004; Foa, 2006; Frueh, Grubaugh, Cusack, & Elhai, in press), integrating it with existing treatments and programs for adults with SMI, in order to improve mental health service delivery for this underserved group.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by grants MH065248 and MH074468 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and by support from the Menninger and McNair Foundations. We are grateful for the support and collaboration of the South Carolina Department of Mental Health and the Charleston/Dorchester Community Mental Health Centers. We also wish to acknowledge important contributions by: Deborah C. Beidel, Jennifer Bennice, Todd C. Buckley, Victoria C. Cousins, Deborah DiNovo, Thom G. Hiers, Terence M. Keane, Mary Long, Chris Molnar, Kim T. Mueser, Emma Rhodes, Julie A. Sauvageot, Samuel M. Turner, Chris Wells, Eunsil Yim, and Heidi M. Zinzow.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, Nutt DJ, Foa EB, Kessler RC, McFarlane AC, Shalev AY. Consensus statement on posttraumatic stress disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 5):60–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough C, Haddock G, Lobban F, Jones S, Siddle R, Roberts C, Gregg L. Group cognitive-behavioural therapy for schizophrenia. Randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:527–532. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rector NA. Cognitive therapy of schizophrenia: A new therapy for the new millennium. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2000;54:291–300. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2000.54.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Darius E, Schaumberg K. An analog study of patient preferences for exposure versus alternative treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2861–2873. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LN, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. the Behavior Therapist. 1990;18:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw W. Integrating cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for persons with schizophrenia into a psychiatric rehabilitation program: Results of a three year trial. Community Mental Health Journal. 2000;36:491–500. doi: 10.1023/a:1001911730268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Dansky BS, Back SE, Foa EB, Carroll KM. Exposure therapy in the treatment of PTSD among cocaine-dependent individuals: Preliminary findings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;21:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SP, Foa EB, Hembree EA, Marshall RD, Nacash N. Dissemination of exposure therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:597–610. doi: 10.1002/jts.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JJ, Schnurr PP, Foa EB. Bridging the gap between posttraumatic stress disorder research and clinical practice: The example of exposure therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2004;41:374–387. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran C, Walker E, Huot R, Mittal V, Tessner K, Kestler L, Malaspina D. The stress cascade and schizophrenia: Etiology and onset. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29:671–692. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack KJ, Frueh BC, Brady KT. Trauma history screening in a Community Mental Health Center. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:157–162. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack KJ, Grubaugh AL, Knapp RG, Frueh BC. Unrecognized trauma and PTSD among public mental health consumers with chronic and severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal. 2006;42:487–500. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack KJ, Wells CB, Grubaugh AL, Hiers TG, Frueh BC. The South Carolina Trauma Initiative 7 Years Later. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:708–710. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB. Cognitive behavioral psychotherapy for schizophrenia: A review of recent empirical studies. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;43:71–90. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeburua E, de Corral P, Zubizarreta I, Sarasua B. Psychological treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of sexual aggression. Behavior Modification. 1997;21:433–456. doi: 10.1177/01454455970214003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB. Psychosocial treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 5):49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB. Psychosocial therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 2):40–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Dancu CV, Hembree EA, Jaycox LH, Meadows EA, Street GP. A comparison of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training, and their combination for reducing posttraumatic stress disorder in female assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:194–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SA, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, Yadin E. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure of posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: Outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Riggs DS, Murdock TB. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:715–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Buckley TC, Cusack KJ, Kimble MO, Grubaugh AL, Turner SM, Keane TM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD among people with severe mental illness: A proposed treatment model. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2004;10:26–38. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Cusack KJ, Grubaugh AL, Sauvageot JA, Wells C. Clinician perspectives on cognitive behavioral treatment for PTSD among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:1027–1031. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Cousins VC, Hiers TG, Cavanaugh SD, Cusack KJ, Santos AB. The need for trauma assessment and related clinical services in a state public mental health system. Community Mental Health Journal. 2002;38:351–356. doi: 10.1023/a:1015909611028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Cusack KJ, Hiers TG, Monogan S, Cousins VC, Cavenaugh SD. Improving public mental health services for trauma victims in South Carolina. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:812–814. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Grubaugh AL, Cusack KJ, Buckley TC, Molnar C, Kimble MO, Turner SM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD among people with severe mental illness. Unpublished treatment manual. 2007 doi: 10.1097/00131746-200401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Grubaugh AL, Cusack KJ, Elhai JD. Disseminating evidence-based practices for adults with PTSD and severe mental illness in public-sector mental health agencies. Behavior Modification. doi: 10.1177/0145445508322619. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Monnier J, Grubaugh AL, Elhai JD, Yim E, Knapp R. Therapist adherence and competence with manualized cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD delivered via videoconferencing technology. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:856–866. doi: 10.1177/0145445507302125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Pellegrin KL, Elhai JD, Hamner MB, Gold PB, Magruder KM, Arana GW. Patient satisfaction among combat veterans receiving specialty PTSD treatment. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2002;8:326–332. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Turner SM, Beidel DC. Exposure therapy for combat-related PTSD: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 1995;15:799–817. [Google Scholar]

- Frueh BC, Turner SM, Beidel DC, Mirabella RF, Jones WJ. Trauma Management Therapy: A preliminary evaluation of a multicomponent behavioral treatment for chronic combat-related PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:533–543. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano B. Cognitive behavior therapies for psychotic disorders: Current empirical status and future directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, Drake RE. Physical and sexual assault history in women with serious mental illness: Prevalence, correlates, treatment, and future research directions. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1997;23:685–96. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Salyers MP, Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD, Swartz M, Essock SM, Osher FC, Butterfield MI. Recent victimization in women and men with severe mental illness: Prevalence and correlates. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:615–632. doi: 10.1023/A:1013026318450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Thompson KM, Weinfurt K, Corl S, Acker P, Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD. Reliability of reports of violent victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder among men and women with serious mental illness. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12:587–599. doi: 10.1023/A:1024708916143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RA, Mueser KT, Bolton E, Mays V, Goff D. Cognitive therapy for psychosis in schizophrenia: An effect size analysis. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;30:335–342. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Davidson JR, Ballenger JC, Fyer AJ. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60:427–435. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh AL, Elhai JD, Cusack KJ, Wells C, Frueh BC. Screening for PTSD in public-sector mental health settings: The diagnostic utility of the PTSD Checklist. Depression and Anxiety. 2007;24:124–129. doi: 10.1002/da.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. DHEW; Washington D.C.: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hamblen JL, Jankowski MK, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT. CBT treatment for PTSD in people with severe mental illness: Three case studies. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2004;7:147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamner MB, Frueh BC, Ulmer HG, Arana GW. Psychotic features and illness severity in combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:846–852. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss MT, Leak GK, Davis SF. A validation study of the Novaco Anger Inventory. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1993;31:279–281. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council . Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: An assessment of the evidence. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and to society. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61(supple 5):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble MO. Treating PTSD in the presence of multiple comorbid disorders. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2000;7:133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of controlled research on social skills training for schizophrenia. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:491–504. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefford NL, Donohue B, Strada MJ. Improving session attendance in mental health and substance abuse settings: A review of controlled studies. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little T, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Wiley and Sons; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Magruder KM, Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Johnson MR, Vaughan JA, Carson TC, Powell DA, Hebert R. PTSD symptoms, demographic characteristics, and functional status among veterans treated in VA primary care clinics. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:293–301. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000038477.47249.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik ML, Connor KM, Sutherland SM, Smith RD, Davidson RM, Davidson JR. Quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study assessing changes in SF-36 scores before and after treatment in a placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12:387–393. doi: 10.1023/A:1024745030140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JF, Kroner DG, Forth AE. Novaco Anger Scale: Reliability and validity within an adult criminal sample. Assessment. 1998;5:237–248. doi: 10.1177/107319119800500304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Bolton E, Carty PC, Bradley MJ, Ahlgren KF, DiStaso DR, Gilbride A, Liddell C. The Trauma Recovery Group: A cognitive behavioral program for posttraumatic stress disorder in persons with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal. 2007;43:281–304. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Goodman LA, Trumbetta SL, Rosenberg SD, Osher FC, Vidaver R, Auciello P, Foy DW. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:493–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Rosenberg RD, Goodman LA, Trumbetta SL. Trauma, PTSD, and the course of severe mental illness: An interactive model. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;53:123–143. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Rosenberg RD, Jankowski MK, Hamblen JL, Descamps J. A cognitive-behavioral treatment program for posttraumatic stress disorder in persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2004;7:107–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Rosenberg RD, Xie H, Jankowski MK, Bolton EE, Lu W, Hamblen JL, Rosenberg HJ, McHugo GJ, Wolfe R. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:259–271. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Rosenberg SD, Ford JD, Fox L, Carty P. Psychometric evaluation of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder assessments in persons with severe mental illness. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:110–117. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Essock SM, Osher FC, Swartz MS, Butterfield MI, 5 Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee Interpersonal trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with severe mental illness: Demographic, clinical, and health correlates. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30:45–57. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Clinical Evidence . Clinical guideline 1: Schizophrenia. Core interventions in the treatment and management of schizophrenia in primary and secondary care. NICE; London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Novaco RW. Anger control: The development of an experimental treatment. Lexington; Lexington, KY: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrin KL, Stuart GW, Maree B, Frueh BC, Ballenger JC. A brief scale for assessing patients’ satisfaction with care in outpatient psychiatric services. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:816–819. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, Garety P, Geddes J, Orbach G, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behavior therapy. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:763–782. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Best CL, Kilpatrick DG, Freedy JR, Falsetti SA. Trauma Assessment for Adults—Interview Version. Unpublished scale. Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center, Medical University of South Carolina; Charleston, SC: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SG, Bond GR, Mueser KT. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in people with schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:415–423. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SD, Lu W, Mueser KT, Jankowski MK, Cournos F. Correlates of adverse childhood events among adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:245–253. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, Friedman MJ, Gorman PG, Drake RE, Vidaver RM, Torrey WC, Jankowski MK. Developing effective treatments for posttraumatic disorders among people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1453–1461. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.11.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, Jankowski MK, Salyers MP, Acker K. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of PTSD in severe mental illness: Results of a pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2004;7:171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Engel CC, Foa EB, Shea MT, Chow BK, Resick PA, Thurston V, Orsillo SM, Haug R, Turner C, Bernardy N. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:820–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Spiro A, Paris AH. Physician-diagnosed medical disorders in relation to PTSD symptoms in older male military veterans. Health Psychology. 2000;19:91–97. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar G. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin M, Dorahy MJ, Adamson G. Trauma and psychosis: An analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:166–169. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Pilgrim H, Sommerfield C, Faragher B, Reynolds M, Graham E, Barrowclough C. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:13–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkington D, Dudley R, Warman DM, Beck AT. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: A review. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2004;10:5–16. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200401000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkington D, Kingdom D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:365–373. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SM, Beidel DC, Cooley MR, Woody SR, Messer SC. A multicomponent behavioral treatment for social phobia: Social Effectiveness Therapy. Behaviour Research Therapy. 1994;32:381–390. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SM, Frueh BC, Beidel DC. Multicomponent behavioral treatment for chronic combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Trauma Management Therapy. Behavior Modification. 2005;29:39–69. doi: 10.1177/0145445504270872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E, Diforio D. Schizophrenia: A neural diathesis-stress model. Psychological Review. 1997;104:667–685. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short Form Health Survey. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JR. Clinician-administered PTSD scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz B. Psychometric properties of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, CAPS-1. PTSD Research Quarterly. 1994;5:2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:124–133. [Google Scholar]