Abstract

Background

Dramatic increases in patients requiring linkage to HIV treatment are anticipated in response to updated CDC HIV testing recommendations advocating routine, opt-out testing.

Methods

A retrospective analysis nested within a prospective HIV clinical cohort study evaluated patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment at the University of Alabama at Birmingham 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2005. Survival methods were used to evaluate the impact of missed visits in the first year of care on subsequent mortality in the context of other baseline sociodemographic, psychosocial, and clinical factors. Mortality was ascertained by query of the Social Security Death Index as of 1 August 2007.

Results

Among 543 study participants initiating outpatient HIV care, 60% missed a visit in the first year. Mortality was 2.3 per 100 person-years for patients who missed visits compared with 1.0 per 100 person-years for those who attended all scheduled appointments during the first year after establishing outpatient treatment (P=0.02). In Cox proportional hazards analysis, higher hazards of death were independently associated with missed visits (HR=2.90, 95%CI=1.28–6.56), older age (HR=1.58 per 10 years, 95%CI=1.12–2.22), and baseline CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (HR=2.70, 95%CI=1.00–7.30).

Conclusions

Patients who missed visits in the first year after initiating outpatient HIV treatment had more than twice the rate of long-term mortality relative to those who attended all scheduled appointments. We posit that early missed visits are not causally responsible for the higher observed mortality, but rather identify patients more likely to exhibit health behaviors that portend increased subsequent mortality.

Introduction

In September 2006, the United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released updated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing recommendations advocating routine, opt-out HIV testing for adults in all health care settings [1]. The rationale for this paradigm shift from risk-based opt-in to routine opt-out testing included the high proportion of HIV-infected individuals unaware of their status, the common occurrence of late diagnosis with advanced disease progression, and the consistently high number of incident HIV cases reported annually despite extensive prevention efforts. An estimated 25% of individuals living with HIV infection in the US are unaware of their status [2]. Further, late presentation is frequently observed with upwards of half of newly diagnosed patients entering care with initial CD4+ counts below 200 cells/mm3 [3–7]. The updated recommendations aim to reduce the number of infected persons unaware of their status and to facilitate earlier diagnosis of HIV infection [1], which may ultimately benefit the health of both individuals as well as the public health through reduced transmission and secondary infections.

Dramatic increases in the number of individuals in need of HIV treatment are anticipated in response to implementation of the updated CDC HIV testing recommendations [8, 9]. The recommendations emphasize the importance of linkage to clinical and preventive services for newly diagnosed patients [1]. Studies show that 20–40% of recently diagnosed HIV-infected patients fail to attend an outpatient clinic visit within 6 months of their diagnosis [10, 11]. Among those who successfully initiate outpatient care, missed visits and loss to follow-up in the year after attending a first HIV clinic visit are common and associated with delays in receipt of antiretroviral medications [7, 12, 13]. However, to our knowledge, no published study has evaluated the relationship between missed visits in the first year of HIV care and long-term survival. We hypothesized that patients who missed visits in the year after establishing outpatient HIV treatment would have higher subsequent mortality in the context of other baseline sociodemographic, psychosocial, and clinical factors associated with survival.

Methods

Cohort description

The UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic Cohort Observational Database Project (UAB 1917 Clinic Cohort) is described in detail elsewhere [14–16]. Here, we conduct a retrospective cohort study nested in the UAB 1917 Clinic Cohort to evaluate the impact of missed visits on long-term survival in patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment.

Eligibility criteria

Patients who attended an initial primary HIV care visit at the 1917 Clinic between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2005 and received no prior outpatient HIV treatment at another facility were included in this analysis. Medical records of patients attending a first visit at the 1917 Clinic during the study period were reviewed independently by two abstractors (J.S.R. and S.A.) to determine if a patient previously received HIV treatment elsewhere and was therefore ineligible for study participation. Discrepancies in reporting (<2% of records) were arbitrated by two physician HIV care providers at the 1917 Clinic (M.J.M. and J.H.W.). These criteria were employed because of our interest in studying a homogeneous sample of patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment, while excluding patients who previously received care at other facilities, who represent a different sample. Because we were interested in evaluating the impact of missed visits in the first year after establishing care (exposure) on long-term survival (outcome), patients who died within one year of their initial visit were excluded from analyses since they did not have appointment attendance data for the entire exposure period.

Measures

Appointment attendance in the first year after establishing outpatient care was the primary independent variable of interest. Missed visit status was determined for all study participants by evaluating appointment attendance records for 365 days following an initial attended primary HIV care visit. Urgent care and subspecialty visits (e.g., dermatology) at the clinic were excluded. Appointment status at the 1917 Clinic is managed with a web-based software program that is updated daily. Consistent with previous studies [17–20], only missed visits that a patient did not call the clinic to cancel or reschedule (“no show” visits) were included in the missed visit measure. Appointments cancelled by the clinic or those that a patient called ahead to cancel, or was hospitalized, are not included in the missed visit measure. Missed visit status was recorded as a dichotomous measure with patients characterized as having no missed visits or ≥1 missed visit in the first year of outpatient HIV treatment.

Other covariates were selected a priori and included sociodemographic (age, sex, race, HIV risk group, and insurance status), psychosocial (affective mental health, substance abuse, and alcohol abuse disorders), and clinical measures (baseline CD4 count, plasma HIV RNA, and receipt of antiretroviral therapy in the first year of care). All measures were determined by query of the 1917 Clinic Cohort Database; which includes psychosocial measures captured from diagnosis lists in patients’ medical records. All cause mortality, the primary outcome measure, was ascertained by an electronic query of the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) performed on 1 August 2007.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed for all study variables to evaluate distributions and to ensure assumptions of statistical tests to be employed were met. Unadjusted analyses using chi square tests and logistic regression, and multivariable logistic regression analysis controlling for the aforementioned covariates were used to evaluate factors associated with patients missing a primary HIV care clinic visit in the first year after establishing initial outpatient care. The discriminative capacity and fit of the multivariable model were assessed by the C-statistic and Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, respectively.

A Kaplan-Meier plot was used to evaluate long-term survival in patients according to missed visit status in the first year of outpatient HIV care. Unadjusted and an adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards model were used to evaluate factors associated with long-term survival. Because of the relatively modest number of deaths relative to the number of covariates in the primary Cox model, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using propensity score methods [21]. Briefly, a propensity score for “missed visit” was determined for all study participants using the multivariable logistic regression model evaluating missed visit status in the year of HIV treatment. This approach serves to combine covariates into a single propensity score thereby reducing the number of variables and addressing potential concerns of model over-fitting. Next, a Cox Proportional Hazards model evaluated the relationship between missed visit status and long-term survival while adjusting for propensity score as well as antiretroviral medication receipt during the first year in treatment. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.0 (SAS Corporation, Cary, NC).

Results

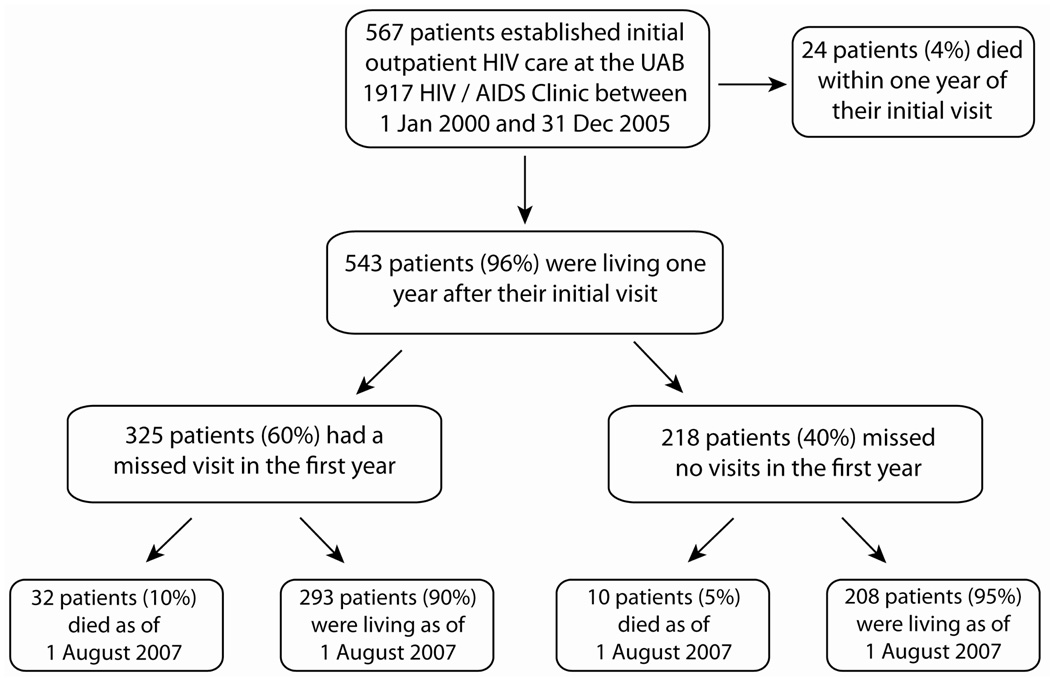

During the study period, 567 of 1,165 patients (49%) attending a first primary HIV care visit at the UAB 1917 Clinic had not previously received HIV care elsewhere and were establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Twenty-four patients (4%) died within one year of their initial visit, leaving 543 patients who were included in statistical analyses. Sociodemographic, psychosocial, and clinical characteristics among the study sample (n=543) were largely similar to the overall population (n=1165) (data not shown). Among the 543 study participants, 325 patients (60%) had a missed visit in the first year of care (mean ± SD = 1.8 ± 1.1 missed visits), while 218 patients (40%) attended all scheduled appointments. Mortality was observed in 32 patients (10%) with missed visits and 10 patients (5%) with perfect appointment attendance during longitudinal follow-up (Figure 1). Among the 325 patients with missed visits in the first year of care, a similar number of missed visits (mean ± SD) were observed in patients who died (n=32, 1.9 ± 1.6 missed visits) and survived (n=293, 1.8 ± 1.1 missed visits) during follow-up.

Figure 1.

Short-term (1 year) and long-term vital status of 567 HIV-infected patients establishing initial outpatient HIV care at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic between 1 January 2000 – 31 December 2005. Among the 543 patients who were living one year after their initial attended visit, observed mortality was 2.3 and 1.0 per 100 patient-years follow-up for those with and without a missed visit in the first year, respectively (P=0.02). Only missed visits that patients did not call ahead to notify the clinic that they would not attend their appointment were included in this measure (“no show” visits). Appointments cancelled by a patient in advance, those scheduled while a patient was hospitalized, and those cancelled by the clinic are not included in the missed visit measure. Vital status was determined by query of the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) as of 1 August 2007.

Baseline characteristics of study participants (n=543) include a mean age (± SD) of 37.7 ± 9.4 years, 25% were female, and 54% were African American (Table 1). HIV risk group was men who have sex with men (MSM) in 52%, heterosexual transmission in 40%, and intravenous drug use (IVDU) in 8%. At initial presentation for care, half of study patients lacked private health insurance (15% public insurance, 35% uninsured). Affective mental health, substance abuse, and alcohol abuse disorders were documented in 48%, 26%, and 20% of patients, respectively. The mean (± SD) baseline log 10 HIV RNA was 4.4 ± 1.1, 38% had a baseline CD4 count <200 cells/mm3, and 67% of patients were prescribed antiretroviral therapy in the first year of care. Compared to the 543 patients included in the analysis, the 24 patients who died in the first year were more likely to have baseline CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3 (P<0.01), lack private health insurance (P<0.01), and belong to an HIV risk group other than MSM (P<0.01, data not shown).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 543 patients who were living one year after establishing initial outpatient HIV care at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2005.a

| Characteristic (N=543) | Mean ± standard deviation or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (range 19–70 years) | 37.7 ± 9.4 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 410 (75.5) |

| Female | 133 (24.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 250 (46.0) |

| African American | 293 (54.0) |

| HIV risk factor | |

| Men who have sex with men (MSM) | 277 (51.6) |

| Heterosexual | 215 (40.0) |

| Intravenous drug use (IVDU) | 45 ( 8.4) |

| Health insurance | |

| Private | 273 (50.3) |

| Public | 79 (14.6) |

| Uninsured | 191 (35.2) |

| Affective mental health disorder | |

| No | 280 (51.6) |

| Yes | 263 (48.4) |

| Substance abuse | |

| No | 401 (73.9) |

| Yes | 142 (26.1) |

| Alcohol abuse | |

| No | 437 (80.5) |

| Yes | 106 (19.5) |

| Baseline CD4 count | |

| < 200 cells/mm3 | 205 (38.2) |

| 200 – 350 cells/mm3 | 95 (17.7) |

| ≥ 350 cells/mm3 | 237 (44.1) |

| Baseline Viral Load (log10) | 4.4 ± 1.1 |

| Missed visit in first year b | |

| No | 218 (40.2) |

| Yes | 325 (59.8) |

| Antiretroviral therapy started in first year | |

| No | 177 (32.6) |

| Yes | 366 (67.4) |

Among 567 patients who established initial outpatient care during this time period, 543 (96%) were alive one year after their first clinic visit.

Only missed visits that patients did not call ahead to notify the clinic that they would not attend their appointment were included in this measure (“no show” visits). Appointments cancelled by a patient in advance, those scheduled while a patient was hospitalized, and those cancelled by the clinic are not included in the missed visit measure.

Factors associated with missed visits in the first year of care

In unadjusted analyses, missed visits in the first year of HIV care were more common in younger patients, females, African Americans, HIV risk groups other than MSM, patients lacking private health insurance, and those with substance abuse disorders (Table 2). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, missed visits were associated with younger age (OR=0.81 per 10 years, 95%CI=0.66–0.99), African American race (OR=2.74, 95%CI=1.77–4.23) and public health insurance (OR=2.09, 95%CI=1.10– 3.96), and inversely associated with a baseline CD4 count of 200–350 cells/mm3 (vs. ≥350 cells/mm3 OR=0.59, 95%CI=0.37–0.92, Table 2). Propensity scores for “missed visits” were determined for each study participant using this multivariable model, which were subsequently employed in the long-term survival sensitivity analysis.

Table 2.

Factors associated with missing an outpatient HIV clinic appointment in the first year of care among 543 patients who were living one year after establishing initial outpatient HIV care at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic, 2000–2005.

| Characteristic | No Missed Visita (N=218) |

Missed Visita (N=325) |

Unadjusted OR (95%CI) for Missed Visit |

Adjusted OR (95%CI) for Missed Visitb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 years) | 38.9 ± 9.6 | 36.9 ± 9.2 | 0.79 (0.66–0.95) | 0.81 (0.66– 0.99) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 180 (82.6) | 230 (70.8) | 1.0 | 1 |

| Female | 38 (17.4) | 95 (29.2) | 1.96 (1.28–2.99) | 1.11 (0.62– 1.98) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 134 (61.5) | 116 (35.7) | 1.0 | 1 |

| African American | 84 (38.5) | 209 (64.3) | 2.87 (2.02–4.10) | 2.74 (1.77– 4.23) |

| HIV risk factor | ||||

| Men who have sex with men (MSM) | 133 (61.3) | 144 (45.0) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Heterosexual | 72 (33.2) | 143 (44.7) | 1.83 (1.27–2.65) | 1.23 (0.73– 2.06) |

| Intravenous drug use (IVDU) | 12 ( 5.5) | 33 (10.3) | 2.54 (1.26–5.12) | 1.82 (0.78– 4.25) |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Private | 129 (59.2) | 144 (44.3) | 1.0 | 1 |

| Public | 18 ( 8.2) | 61 (18.8) | 3.04 (1.71–5.41) | 2.09 (1.10– 3.96) |

| Uninsured | 71 (32.6) | 120 (36.9) | 1.51 (1.04–2.21) | 1.23 (0.81– 1.86) |

| Affective mental health disorder | ||||

| No | 105 (48.2) | 175 (53.9) | 1.0 | 1 |

| Yes | 113 (51.8) | 150 (46.1) | 0.80 (0.57–1.12) | 0.91 (0.61– 1.35) |

| Substance abuse | ||||

| No | 174 (79.8) | 227 (69.9) | 1.0 | 1 |

| Yes | 44 (20.2) | 98 (30.1) | 1.71 (1.14–2.56) | 1.60 (0.93– 2.74) |

| Alcohol abuse | ||||

| No | 174 (79.8) | 263 (80.9) | 1.0 | 1 |

| Yes | 44 (20.2) | 62 (19.1) | 0.93 (0.61–1.43) | 0.82 (0.50– 1.34) |

| Baseline Viral Load (log10) | 4.4 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | 1.01 (0.84– 1.20) |

| Baseline CD4 count | ||||

| ≥ 350 cells/mm3 | 73 (34.0) | 132 (41.0) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 200 – 350 cells/mm3 | 36 (16.7) | 59 (18.3) | 0.68 (0.47–1.00) | 0.59 (0.37–0.92) |

| < 200 cells/mm3 | 106 (49.3) | 131 (40.7) | 0.91 (0.25–1.50) | 0.76 (0.44–1.31) |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or N (%). Only missed visits that patients did not call ahead to notify the clinic that they would not attend their appointment were included in this measure (“no show” visits). Appointments cancelled by a patient in advance, those scheduled while a patient was hospitalized, and those cancelled by the clinic are not included in the missed visit measure.

Multivariable logistic regression model characteristics: Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit p-value=0.19, C-statistic=0.71

Factors associated with long-term survival

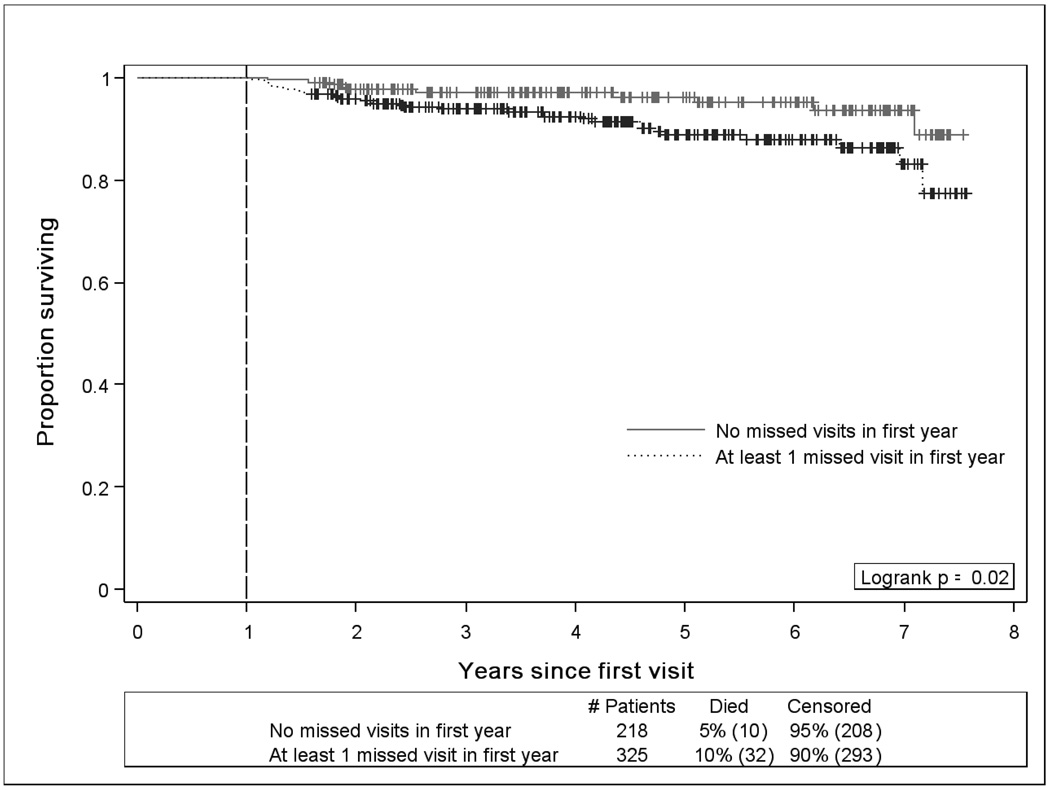

Kaplan Meier survival analysis revealed lower survival rates for patients who missed a visit in the year after establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment (P=0.02, Figure 2). Observed mortality was 2.3 per 100 patient-years follow-up for patients who missed a visit vs. 1.0 per 100 patient-years follow-up for those who attended all clinic visits in the first year of HIV care. In univariate survival analyses, older patients, those with public health insurance, and patients who missed a visit in the first year of care had higher hazards of mortality (Table 3). Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis revealed higher hazards of death in older patients (HR=1.58 per 10 years, 95%CI=1.12–2.22), patients with baseline CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3 (HR=2.70, 95%CI=1.00–7.30), and those who missed a visit in the first year of treatment (HR=2.90, 95%CI=1.28–6.56). Similar hazards of death were observed in patients with 1 missed visit and ≥2 missed visits relative to patients who had no missed visits in the first year of outpatient treatment (data not shown). No other socio-demographic or psychosocial factors were significantly associated with long-term mortality, and receipt of antiretroviral therapy in the first year of care was not associated with reduced hazards of death in subsequent years (Table 3). Sensitivity analysis using propensity score methods yielded similar findings to the primary analysis with missed visits in the first year of care increasing the hazards of long-term mortality (HR=2.52, 95%CI=1.15–5.52) while controlling for propensity for a “missed visit” and antiretroviral receipt (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV care at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2005 catgegorized by missed visit status in the first year of care. Among 567 patients, 543 patients (96%) were living one year after their initial visit; observed mortality was 2.3 and 1.0 per 100 patient-years for those with and without a missed visit in the first year, respectively (P=0.02). Only missed visits that patients did not call ahead to notify the clinic that they would not attend their appointment were included in this measure (“no show” visits). Appointments cancelled by the clinic and those scheduled while a patient was hospitalized are not included in the missed visit measure. Vital status was determined by query of the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) as of 1 August 2007.

Table 3.

Factors associated with long-term survival among 543 patients who were living one year after establishing initial outpatient HIV care at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic, 2000–2005.

| Primary Analysisa | ||

|---|---|---|

| Univariate HR (95% CI) |

Multivariable HR (95% CI)a |

|

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.61 (1.21–2.17) | 1.58 (1.12–2.22) |

| Female | 1.11 (0.56–2.20) | 1.20(0.49–2.96) |

| African American | 1.05 (0.57–1.93) | 0.73 (0.33–1.64) |

| HIV risk factor | ||

| Men who have sex with men (MSM) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Heterosexual | 1.23 (0.62–2.43) | 0.91 (0.38–2.20) |

| Intravenous drug use (IVDU) | 2.06 (0.81–5.23) | 1.05 (0.33–3.31) |

| Health insurance | ||

| Private | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Public | 2.11 (1.03–4.32) | 1.30 (0.54–3.14) |

| Uninsured | 0.79 (0.37–1.68) | 0.74 (0.32–1.71) |

| Affective mental health disorder | 0.80 (0.44–1.47) | 0.80 (0.39–1.62) |

| Substance abuse | 1.80 (0.96–3.35) | 2.08 (0.86–5.07) |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.12 (0.53–2.35) | 0.75 (0.31–1.84) |

| Baseline CD4 count | ||

| ≥ 350 cells/mm3 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 200 – 350 cells/mm3 | 1.32 (0.48–3.65) | 1.49 (0.47– 4.67) |

| < 200 cells/mm3 | 2.00 (0.95–4.20) | 2.70 (1.00–7.30) |

| Baseline Viral Load (log10) | 1.11 (0.84–1.48) | 1.02 (0.75–1.39) |

| Missed visit in first year | 2.34 (1.15–4.77) | 2.90 (1.28– 6.56) |

| Antiretroviral therapy started in first year | 1.00 (0.51–1.93) | 0.64 (0.25–1.62) |

| Propensity Score Sensitivity Analysisb | ||

|

Univariate HR (95% CI) |

Multivariable HR (95% CI)b |

|

| Missed visit in first year | 2.34 (1.15–4.77) | 2.52 (1.15–5.52) |

| Antiretroviral therapy started in first year | 1.00 (0.51–1.93) | 1.18 (0.58–2.41) |

| Propensity score for missed visit (per 10%) | 1.05 (0.87–1.26) | 0.98 (0.80–1.19) |

Primary analysis; Cox proportional hazards model (multivariable HR) includes variables listed in the table (age, sex, race, HIV risk factor, health insurance, affective mental health disorder, substance abuse, alcohol abuse, baseline CD4 count, baseline viral load, missed visit status in the first year, and antiretroviral therapy receipt in first year).

Sensitivity analysis; Cox proportional hazards model includes missed visit status in the first year, propensity score for missed visit in first year (derived from multivariable logistic regression model in table 2; includes age, sex, race, HIV risk factor, health insurance, affective mental health disorder, substance abuse, alcohol abuse, baseline CD4 count, baseline viral load), and antiretroviral therapy receipt in the first year.

Discussion

Missed primary HIV care visits in the year after establishing initial outpatient treatment were associated with subsequent mortality, even when controlling for baseline CD4 count and antiretroviral receipt in the first year. Mortality rates were more than two times higher for patients with missed visits relative to those who attended all scheduled appointments in the first year of care (2.3 vs. 1.0 per 100 patient-years follow-up, respectively, P=0.02). Although a modest absolute difference in mortality rates was observed, these findings may have profound public health implications. Because tens of thousands of newly diagnosed patients require linkage to HIV care in the US annually [22], extrapolation of our findings to the population level results in considerable mortality, particularly in light of the high proportion of patients who miss visits shortly after establishing outpatient HIV treatment [7, 12].

We posit that missed visits in the first year of care are not causally responsible for reduced long-term survival, but rather may identify a subset of patients whose health behaviors portend increased mortality. Among these, we speculate that worse subsequent retention in care and antiretroviral medication adherence among those with missed visits, ultimately places them at increased risk of death. Accordingly, missed visits in patients establishing initial outpatient treatment may serve as a marker in identifying individuals at risk for poor future health outcomes.

The current study advances earlier research by focusing upon patients establishing initial linkage to outpatient HIV treatment, a vulnerable population that has not been well evaluated previously and is expected to increase dramatically in coming years [8, 9]. Studies assessing survival in patients with HIV infection typically focus on individuals starting antiretroviral therapy or samples participating in on-going cohort studies [23–32]. Many new patients miss appointments and/or are lost-to-follow-up shortly after attending an initial clinic visit, often failing to initiate antiretroviral therapy as a result [7, 12, 13]. Further, antiretroviral medications may not be indicated in patients establishing care based upon baseline CD4 counts and plasma HIV RNA levels [33]. Among our sample, one-third of patients did not receive antiretroviral therapy in the first year of outpatient HIV treatment, a group who would not have been evaluated if the current study employed inclusion criteria based on antiretroviral initiation. As such, the evaluation of missed visits and other factors associated with survival in patients initiating outpatient HIV care complements earlier research and provides novel insight into an understudied group. Our finding that 60% of patients missed at least one visit in the first year of care underscores the importance of the higher observed mortality in this group. These results may be applied in clinical practice to identify a priority population and inform the development of focused interventions designed to improve long-term survival among new patients initiating outpatient HIV treatment.

Similar to the association between missed visits and mortality in patients establishing HIV care observed in this study, a relationship between retention in care and survival in patients starting antiretroviral therapy was recently reported [23, 30]. In a study of HIV-infected males receiving treatment through the Veterans Administration system, Giordano and colleagues also found a significant relationship between retention in care and antiretroviral medication adherence [23], supporting our hypothesis that missed visits may identify patients at risk for worse outcomes via this mechanism during subsequent care.

In addition to those with missed outpatient appointments, higher mortality rates were observed among older patients and those with more advanced HIV infection when establishing outpatient treatment in our study. These findings are important as older patients account for an increasing proportion of newly diagnosed patients establishing HIV care [22]. Further, recent studies have found upwards of 50% of newly diagnosed patients presenting for initial care have baseline CD4 counts below 200 cells/mm3 [3–6], a group with higher rates of observed mortality in this study. Part of the rationale behind the updated CDC HIV testing recommendations is the desire to facilitate earlier diagnosis and linkage to HIV care prior to advanced disease progression [1]. This study suggests there may be long-term benefit to patient survival if these recommendations are successfully implemented and result in the improved timeliness of HIV diagnosis. Accordingly, our findings provide empiric evidence to support the CDC HIV testing recommendations and may serve as a call to action for health care providers.

Notably, receipt of antiretroviral therapy in the first year of care was not associated with subsequent mortality. Following antiretroviral treatment initiation, continuous receipt of medications is necessary to achieve optimal clinical outcomes. Importantly, initial receipt of antiretroviral medications does not necessarily translate to subsequent long-term treatment; patients are often lost-to-follow-up after establishing HIV care [7, 12, 13]. It is possible that patients with missed visits in the first year of HIV care had worse subsequent retention and resultant poor longitudinal receipt of and adherence to antiretroviral medications, which contributed to the higher observed long-term mortality among this group.

Our study also contributes additional knowledge regarding engagement in care among HIV-infected individuals, an area of growing interest [34]. In this study, there were strong associations between missed visits and younger age, African American race, and public health insurance. Previously, we found these socio-demographic groups were less likely to attend an initial clinic visit and establish care at our treatment center after calling to schedule an appointment [15]. Similarly, others report that missed visits were more common in these groups who bear a growing and disproportionate burden of the US HIV epidemic [17, 18, 22, 35].

Formative research is needed to better understand barriers and facilitators of clinic attendance and service utilization such that informed interventions may be developed to improve initial linkage and subsequent retention in outpatient HIV care. Case management and patient navigation models hold promise, and may link patients with community resources and provide social support as well as fostering problem-solving skills and building self-efficacy through strength-based approaches thus enabling patients to remain better engaged in care [11, 36]. The impact of these interventions on long-term survival remains to be seen. Successful interventions may have important implications not only for individual patients, but also for the public health and secondary HIV prevention efforts. Patients engaged in treatment may benefit from prevention messages and reduce risk transmission behaviors [37]. Further, reduction of plasma HIV RNA levels in response to antiretroviral therapy may reduce sexual transmission among patients engaging in risk behaviors [38, 39]. Receipt of prevention messages and antiretroviral therapy is contingent upon linkage and retention in outpatient HIV treatment services after diagnosis, highlighting the vital role of engagement in care [34].

The finding of our study should be interpreted with respect to limitations of the current analyses. As with all observational studies we are able to identify associations but cannot attribute causality and there is potential for unmeasured confounding. As a single center study in the Southeast US our findings may not be generalizable to other regions of the country or patient populations. However, our patient population is largely reflective of the sociodemographic composition of the national HIV epidemic [22]. Mental health, substance abuse, and alcohol abuse disorders were recorded from diagnosis lists in the medical record, not using validated instruments. These co-morbid conditions may be under-recognized in clinical practice. Mortality was ascertained by query of the Social Security Death Index, which may experience reporting delays from time of death to entry in the database. However, we have no reason to believe that delayed reporting should differentially impact individuals based on appointment attendance in the first year of care. Accordingly, we do not feel this introduces systematic bias that impacts our findings or their interpretation.

In conclusion, patients with missed visits in the year after establishing initial outpatient HIV care had more than twice the rates of subsequent mortality, even when controlling for baseline CD4 count and antiretroviral receipt in the first year. These findings are particularly relevant in light of revised CDC HIV testing recommendations and the anticipated large increase in newly diagnosed patients requiring linkage to care in coming years [1, 8, 9]. Future research is needed to identify barriers and facilitators to initial connection and early retention in care such that informed interventions may be developed to ensure individuals derive maximal benefits from the tremendous advances in HIV treatment.

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Alabama at Birmingham 1917 Clinic Cohort management team for their assistance with this project (www.uab1917cliniccohort.org).

Financial support: This study was supported by Grant Number K23MH082641 from the National Institute of Mental Health (MJM). The UAB 1917 HIV / AIDS Clinic Cohort Observational Database project receives financial support from the following: UAB Center for AIDS Research (grant P30-AI27767), CFAR-Network of Integrated Clinical Systems, CNICS (grant 1 R24 AI067039-1), and the Mary Fisher CARE Fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. Funders played no role in study design and analysis.

Footnotes

Presented in part: 3rd International Conference on HIV Treatment Adherence, March 17–18, 2008, Jersey City, NJ: Abstract 70.

Financial disclosures: MJM has received recent research funding from Tibotec Therapeutics and Bristol-Myers Squibb. JHW has received research funding from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Virology Fellows Research Program for the 2006–2008 Academic Years. MSS has received recent research funding or consulted for: Adrea Pharmaceuticals, Avexa, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Monogram Biosciences, Panacos, Pfizer, Progenics, Roche, Serono, Tanox, Tibotec, Trimeris, and Vertex. All other authors: no disclosures.

Citations

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glynn M, Rhodes P. Estimated HIV Prevalence in the United States at the end of 2003. Program and abstracts of the National HIV Prevention Conference; June 2005; Atlanta, GA. abstract 595. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dybul M, Bolan R, Condoluci D, et al. Evaluation of initial CD4+ T cell counts in individuals with newly diagnosed human immunodeficiency virus infection, by sex and race, in urban settings. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1818–1821. doi: 10.1086/340650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gay CL, Napravnik S, Eron JJ., Jr Advanced immunosuppression at entry to HIV care in the southeastern United States and associated risk factors. Aids. 2006;20:775–778. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216380.30055.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keruly JC, Moore RD. Immune status at presentation to care did not improve among antiretroviral-naive persons from 1990 to 2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1369–1374. doi: 10.1086/522759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mugavero MJ, Castellano C, Edelman D, Hicks C. Late diagnosis of HIV infection: the role of age and sex. Am J Med. 2007;120:370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, et al. Therapeutic Implications of Timely Linkage and Early Retention in HIV Care. Programs and Abstracts of the 3rd International Conference on HIV Treatment Adherence; March 17–18, 2008; Jersey City, NJ. Abstract 170. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mugavero MJ, Saag MS. HIV care at a crossroads: the emerging crisis in the US HIV epidemic. MedGenMed. 2007;9:58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saag MS. Which policy to ADAP-T: waiting lists or waiting lines? Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1365–1367. doi: 10.1086/508664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.del Rio C, Green S, Abrams C, Lennox J. From diagnosis to undetectable: the reality of HIV/AIDS care in the inner city. Program and abstracts of the 8th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 4–8, 2001; Chicago, IL. abstract S21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. Aids. 2005;19:423–431. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano TP, Visnegarwala F, White AC, Jr, et al. Patients referred to an urban HIV clinic frequently fail to establish care: factors predicting failure. AIDS Care. 2005;17:773–783. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331336652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giordano TP, White AC, Jr, Sajja P, et al. Factors associated with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients newly entering care in an urban clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:399–405. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen RY, Accortt NA, Westfall AO, et al. Distribution of health care expenditures for HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1003–1010. doi: 10.1086/500453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Allison JJ, et al. Failure to establish HIV care: characterizing the "no show" phenomenon. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:127–130. doi: 10.1086/518587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willig JH, Westfall AO, Allison J, et al. Nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor dosing errors in an outpatient HIV clinic in the electronic medical record era. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:658–661. doi: 10.1086/520653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catz SL, McClure JB, Jones GN, Brantley PJ. Predictors of outpatient medical appointment attendance among persons with HIV. AIDS Care. 1999;11:361–373. doi: 10.1080/09540129947983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Israelski D, Gore-Felton C, Power R, Wood MJ, Koopman C. Sociodemographic characteristics associated with medical appointment adherence among HIV-seropositive patients seeking treatment in a county outpatient facility. Prev Med. 2001;33:470–475. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keruly JC, Conviser R, Moore RD. Association of medical insurance and other factors with receipt of antiretroviral therapy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:852–857. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melnikow J, Kiefe C. Patient compliance and medical research: issues in methodology. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:96–105. doi: 10.1007/BF02600211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2006. 2008;Vol. 18 Also available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/

- 23.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, Clinton White A, et al. Retention in Care: A Challenge to Survival with HIV Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hessol NA, Kalinowski A, Benning L, et al. Mortality among participants in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study and the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:287–294. doi: 10.1086/510488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogg RS, Yip B, Chan KJ, et al. Rates of disease progression by baseline CD4 cell count and viral load after initiating triple-drug therapy. Jama. 2001;286:2568–2577. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May M, Sterne JA, Sabin C, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients up to 5 years after initiation of HAART: collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Aids. 2007;21:1185–1197. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328133f285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mugavero MJ, Pence BW, Whetten K, et al. Predictors of AIDS-related morbidity and mortality in a southern U.S. Cohort. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:681–690. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palella FJ, Jr, Baker RK, Moorman AC, et al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:27–34. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palella FJ, Jr, Deloria-Knoll M, Chmiel JS, et al. Survival benefit of initiating antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons in different CD4+ cell strata. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:620–626. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park WB, Choe PG, Kim SH, et al. One-year adherence to clinic visits after highly active antiretroviral therapy: a predictor of clinical progress in HIV patients. J Intern Med. 2007;261:268–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabin CA, Smith CJ, Youle M, et al. Deaths in the era of HAART: contribution of late presentation, treatment exposure, resistance and abnormal laboratory markers. Aids. 2006;20:67–71. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196178.73174.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Sighem AI, van de Wiel MA, Ghani AC, et al. Mortality and progression to AIDS after starting highly active antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2003;17:2227–2236. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200310170-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammer SM, Saag MS, Schechter M, et al. Treatment for adult HIV infection: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. Jama. 2006;296:827–843. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheever LW. Engaging HIV-Infected Patients in Care: Their Lives Depend on It. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1500–1502. doi: 10.1086/517534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kissinger P, Cohen D, Brandon W, Rice J, Morse A, Clark R. Compliance with public sector HIV medical care. J Natl Med Assoc. 1995;87:19–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV System Navigation: an emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21 Suppl 1:S49–S58. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. Aids. 2006;20:143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen MS, Gay C, Kashuba AD, Blower S, Paxton L. Narrative review: antiretroviral therapy to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV-1. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:591–601. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, et al. Rakai Project Study Group. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]