Abstract

Objective To determine whether observable changes in waiting times occurred for certain key elective procedures between 1997 and 2007 in the English National Health Service and to analyse the distribution of those changes between socioeconomic groups as an indicator of equity.

Design Retrospective study of population-wide, patient level data using ordinary least squares regression to investigate the statistical relation between waiting times and patients’ socioeconomic status.

Setting English NHS from 1997 to 2007.

Participants 427 277 patients who had elective knee replacement, 406 253 who had elective hip replacement, and 2 568 318 who had elective cataract repair.

Main outcome measures Days waited from referral for surgery to surgery itself; socioeconomic status based on Carstairs index of deprivation.

Results Mean and median waiting times rose initially and then fell steadily over time. By 2007 variation in waiting times across the population tended to be lower. In 1997 waiting times and deprivation tended to be positively related. By 2007 the relation between deprivation and waiting time was less pronounced, and, in some cases, patients from the most deprived fifth were waiting less time than patients from the most advantaged fifth.

Conclusions Between 1997 and 2007 waiting times for patients having elective hip replacement, knee replacement, and cataract repair in England went down and the variation in waiting times for those procedures across socioeconomic groups was reduced. Many people feared that the government’s NHS reforms would lead to inequity, but inequity with respect to waiting times did not increase; if anything, it decreased. Although proving that the later stages of those reforms, which included patient choice, provider competition, and expanded capacity, was a catalyst for improvements in equity is impossible, the data show that these reforms, at a minimum, did not harm equity.

Introduction

Until recently, hospital waiting times were viewed as an important problem for the National Health Service.1 However, over the past 10 years, as the government in England increased the supply of doctors, increased funding for the health service, set rigid waiting time targets, and (more recently) introduced market based reforms, waiting times have dropped considerably. Yet, whereas NHS waiting times are widely accepted to have fallen between 1997 and 2007, little is known about whether the drop in waiting times has been equitably distributed with respect to socioeconomic status. One of the main fears associated with the later stages of these reforms—which included increased choice for patients, the use of treatment providers from the independent sector, and competition between providers—was whether any improvements in quality or drops in waiting times would come at the expense of equity.2 3 4

We used population-wide, patient level data to examine the extent of any observable changes in waiting times for certain key elective procedures between 1997 and 2007 and to analyse the distribution of those changes between socioeconomic groups. We relate these changes to three distinct periods in government policy during that time: a period from 1997 to 2000 when the government focused on waiting lists, not waiting times, and moderately increased funding; a period from 2001 to 2004 when funding increased dramatically and the government focused on targets and performance management; and a period from 2005 to 2007 when the government expanded supply and introduced patient choice and provider competition.5 6

Methods

We examined patient level, national hospital activity data for day cases and inpatient cases in England from 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2007. The Dr Foster Unit at Imperial College London processed and cleaned the data before passing them to Dr Foster Intelligence in an anonymised form. We examined three common, high volume elective surgical procedures that all had chronically long waiting times: knee replacement (OPCS4 codes W40.1, W41.1, and W42.1), hip replacement (OPCS4 codes W37.1, W38.1, and W39.1), and cataract repair (OPCS4 code C71.2). We looked at non-revision cases for all three procedures.

Observations were limited to patients seeking elective care from their usual place of residence. Observations were excluded if they had any missing data fields—for example, if the month or year the patient was treated, the patient’s deprivation status, or the patient’s age was missing. No correlation existed between missing data and area, deprivation, year, or patient’s age; any missing data seemed to be the result of coding errors, which were random. We also excluded observations for which a patient’s waiting time was greater than three years. We assumed that any case with a waiting time greater than three years was atypical and should not be reflected in a macro analysis of waiting times.

The data retain individual patients’ postcodes (which are removed before delivery to Dr Foster Intelligence). This allows observations to be linked to patients’ local area characteristics. We calculated deprivation by using the 2001 Carstairs index of deprivation at the output area level and broke the level of deprivation into population fifths. The Carstairs index of deprivation is a composite deprivation index based on car ownership, unemployment, overcrowding, and social class within output areas, calculated by the Office of National Statistics.7 The Carstairs index serves as our proxy for patients’ socioeconomic status. In our study, deprivation 1 was the least deprived fifth and deprivation 5 was the most deprived fifth.

Waiting times were measured as the time from when the patient was referred by a specialist for surgery to the time the patient actually had surgery. We thus measured time from the decision to admit until the actual surgery, irrespective of what happened in between. This method is quite different from the reported waiting time method used by the English Department of Health. For instance, Department of Health figures will reset the waiting time to zero if a patient does not attend or declines a reasonable offer of admission. Equally, if a patient is unwell or unfit for surgery, this time is subtracted from their waiting time.

We calculated mean and median waiting times for each year and each procedure. We used t tests and Wilcoxon signed rank tests to determine whether a statistically significant difference in mean and median waiting times existed for the periods of 1997-2000, 2001-4, and 2005-7. Those three periods roughly correspond to what have been labelled as the three stages of government policy to tackle waiting times, as noted above.5 We used analysis of variance and non-parametric rank tests to determine whether a statistically significant intra-year variation in waiting times existed between fifths of deprivation.

Finally, we used ordinary least squares regression with robust standard errors to determine whether patients’ deprivation level was associated with waiting times, controlling for the patients’ age, sex, area type (city, town and fringe, hamlet and isolated dwelling, and village), and the year of procedure. We ran regressions on data from three periods that corresponded to changing government policy (1997-2000, 2001-4, and 2005-7) independently.5

No individual patients were identifiable in this study. All data were presented in aggregate form. The Stata10-SE software package was used for statistical analysis.

Results

The total number of observations comprised 444 867 knee replacements, 423 203 hip replacements, and 2 647 235 cataract repairs. In total, 3.8% (16 856) of knee replacement observations, 3.9% (16 416) of hip replacement observations, and 3.0% (78 440) of cataract procedure observations were excluded for missing data. We excluded 734 knee replacement procedures, 534 hip replacement procedures, and 477 cataract procedures because they had waiting times greater than three years. After these amendments, the observations were limited to 427 227 knee replacements, 406 253 hip replacements, and 2 568 318 cataract repairs done in English NHS patients between 1997 and 2007.

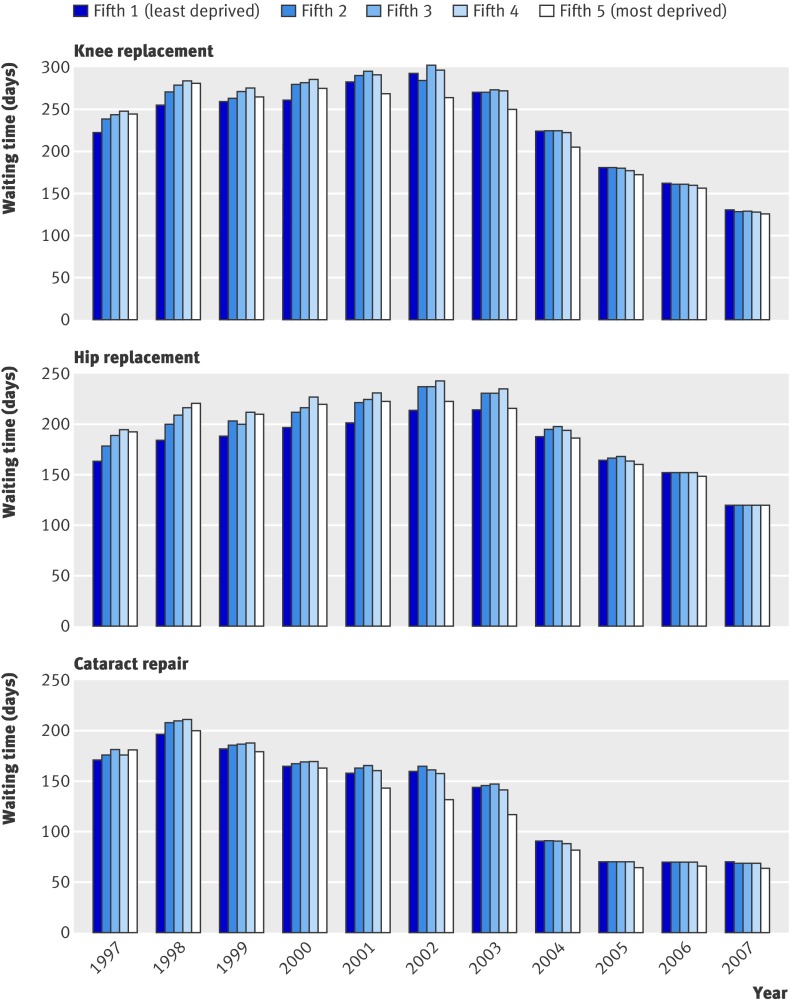

For all three procedures, mean and median waiting times rose initially and then steadily fell (fig 1). However, what is of particular interest for our purposes is what happened to waiting times broken down by socioeconomic status, as measured by the Carstairs index of deprivation. Figure 2 shows mean waiting times for all three procedures, broken down by deprivation. In 1997 deprivation and waiting time tended to be positively related—the greater the degree of deprivation, the longer the waiting time. By 2007 waiting times were much more uniformly distributed across the spectrum of deprivation; for cataract repair and knee replacement, the distribution had actually reversed to show a negative relation between waiting time and deprivation.

Fig 1 Mean and median waiting times for knee replacement, hip replacement, and cataract repair

Fig 2 Mean waiting times for knee replacement, hip replacement, and cataract repair, by deprivation fifth

We found a statistically significant difference in waiting times for each procedure between each of our three periods (P<0.001) determined by t tests and Wilcoxon sign rank tests. Statistical significance at this level was maintained with a Bonferroni correction to account for the possibility of random events occurring over the study time period. We found a statistically significant intra-year variation in waiting times between deprivation groups for all three procedures for all years, except hip replacements in 2005 and 2006, measured with analysis of variance and Kruskal-Wallis rank tests (P<0.05).

We used ordinary least squares regression to establish the relation between waiting times and fifths of deprivation over the three time periods. Tables 1, 2, and 3 summarise the results for the three procedures. As can be seen from the β coefficients on the socioeconomic status variables for each time period, the relation between waiting times and the deprivation fifths also changed over time. Each unit increase in the β coefficient represents a one day increase in waits. For all three procedures, each successive time period was associated with a statistically significant reduction in waiting times. More interestingly, less variation in waiting times existed across socioeconomic groups over time. For example, for hip replacement surgery in 1997-2000 each successive increase in deprivation fifth was associated with a statistically significant increase in waiting time of between one and two weeks compared with the least deprived fifth (P<0.001). In 2001-4 variations in waiting times between deprivation fifths tended to be large and significant. Each procedure showed a modified U shaped distribution, with the middle fifths waiting the longest for care. In 2005-7 very little difference existed in days waited depending on patients’ deprivation fifth. In fact, patients from the most deprived fifth having either a knee replacement or a cataract repair waited less than patients from the least deprived fifth (P<0.05).

Table 1.

Regression coefficients for knee replacements

| 1997-2000 | 2001-4 | 2005-7 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient (95% CI) | T statistic | β coefficient (95% CI) | T statistic | β coefficient (95% CI) | T statistic | |||

| Deprivation fifth: | ||||||||

| 2 | 6.92 (3.34 to 10.51)*** | 3.78 | 2.22 (−0.23 to 4.67) | 1.78 | 0.44 (−1.02 to 1.91) | 0.59 | ||

| 3 | 12.41 (8.77 to 16.05)*** | 6.68 | 7.14 (4.66 to 9.63)*** | 5.63 | 1.76 (0.26 to 3.27)* | 2.29 | ||

| 4 | 13.86 (10.16 to 17.57)*** | 7.34 | 6.89 (4.32 to 9.47)*** | 5.24 | 0.99 (−0.59 to 2.57) | 1.23 | ||

| 5 | 6.23 (2.30 to 10.17)** | 3.11 | −7.75 (−10.52 to −4.98)*** | −5.49 | −2.74 (−4.49 to −0.99)*** | −3.07 | ||

| Female sex | 3.76 (1.56 to 5.97)** | 3.35 | 2.57 (1.02 to 4.12)** | 3.25 | 2.30 (1.34 to 3.27)*** | 4.67 | ||

| Age: | ||||||||

| 50s | 22.23 (14.11 to 30.36)*** | 5.36 | 14.79 (9.25 to 20.33)*** | 5.23 | 6.68 (3.54 to 9.83)*** | 4.17 | ||

| 60s | 32.43 (24.91 to 39.96)*** | 8.45 | 19.39 (14.20 to 24.59)*** | 7.32 | 5.71 (2.76 to 8.65)*** | 3.79 | ||

| 70s | 28.77 (21.33 to 36.22)*** | 7.58 | 16.97 (11.82 to 22.12)*** | 6.46 | 5.83 (2.91 to 8.76)*** | 3.91 | ||

| 80s | 19.74 (11.93 to 27.55)*** | 4.95 | 12.96 (7.55 to 18.36)*** | 4.70 | 5.59 (2.49 to 8.69)*** | 3.54 | ||

| Year: | ||||||||

| 1998 | 27.16 (24.05 to 30.27)*** | 17.12 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 1999 | 26.06 (23.01 to 29.12)*** | 16.70 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 2000 | 35.00 (31.95 to 38.05)*** | 22.48 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 2002 | NA | NA | −9.48 (−12.10 to −6.85)*** | −7.07 | NA | NA | ||

| 2003 | NA | NA | −33.74 (−36.18 to −31.30)*** | −27.05 | NA | NA | ||

| 2004 | NA | NA | −72.74 (−75.08 to −70.40)*** | −60.85 | NA | NA | ||

| 2006 | NA | NA | NA | NA | −25.85 (−27.13 to −24.58)*** | −39.76 | ||

| 2007 | NA | NA | NA | NA | −48.56 (−49.78 to −47.35)*** | −78.46 | ||

| Observations | 103 492 | NA | 162 317 | NA | 161 468 | NA | ||

| R2 | 0.017 | NA | 0.051 | NA | 0.067 | NA | ||

NA=not applicable.

Model run with robust standard errors; deprivation fifth 1 serves as reference category for deprivation, male is reference category for sex, and under 50 years is reference category for age; model also controls for area type (city, town, hamlet and isolated dwelling, village) and provider type (private, foundation trust, teaching hospital, specialist hospital, traditional NHS); dependent variable=waiting time for knee replacement, measured in days.

*P<0.05.

**P<0.01.

***P<0.001.

Table 2.

Regression coefficients for hip replacements

| 1997-2000 | 2001-4 | 2005-7 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient (95% CI) | T statistic | β coefficient (95% CI) | T statistic | β coefficient (95% CI) | T statistic | |||

| Deprivation fifth: | ||||||||

| 2 | 10.92 (8.08 to 13.77)*** | 7.52 | 10.06 (7.77 to 12.356)*** | 8.6 | 1.78 (0.28 to 3.28)* | 2.32 | ||

| 3 | 16.49 (13.56 to 19.43)*** | 11.00 | 12.70 (10.35 to 15.05)*** | 10.59 | 3.08 (1.54 to 4.62)*** | 3.93 | ||

| 4 | 23.26 (20.18 to 26.35)*** | 14.80 | 17.75 (15.24 to 20.25)*** | 13.88 | 3.05 (1.34 to 4.69)*** | 3.62 | ||

| 5 | 19.73 (16.33 to 23.12)*** | 11.40 | 9.42 (6.63 to 12.21)*** | 6.61 | 2.12 (0.23 to 4.02)* | 2.19 | ||

| Female sex | −7.61 (−9.55 to −5.68)** | −7.71 | −7.02 (−8.58 to −5.45)*** | −8.78 | −1.54 (−2.59 to −0.48)* | −2.86 | ||

| Age: | ||||||||

| 50s | 13.26 (8.58 to 17.95)** | 5.55 | 6.91 (3.01 to 10.81)** | 3.47 | 3.24 (0.68 to 5.80)* | 2.48 | ||

| 60s | 7.16 (2.93 to 11.39)** | 3.31 | 4.09 (0.55 to 7.62)* | 2.26 | 0.10 (−2.22 to 2.42) | 0.08 | ||

| 70s | −3.74 (−7.93 to 0.45) | −1.75 | −4.62 (−8.13 to −1.10)* | −2.57 | −2.32 (−4.61 to −0.03)* | −1.99 | ||

| 80s | −19.17 (−23.77 to −14.57)*** | −8.17 | −17.98 (−21.84 to −14.13)*** | −9.14 | −6.92 (−9.46 to −4.39)*** | −5.35 | ||

| Year: | ||||||||

| 1998 | 20.75 (18.17 to 23.33)*** | 15.74 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 1999 | 22.45 (19.87 to 25.03)*** | 17.06 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 2000 | 34.20 (31.58 to 36.81)*** | 25.65 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 2002 | NA | NA | −3.19 (−5.66 to −0.72) | −2.53 | NA | NA | ||

| 2003 | NA | NA | −20.21 (−22.52 to −17.89) | −17.12 | NA | NA | ||

| 2004 | NA | NA | −52.92 (−55.13 to −50.71) | −46.99 | NA | NA | ||

| 2006 | NA | NA | NA | NA | −21.72 (−23.06 to −20.38)*** | −31.76 | ||

| 2007 | NA | NA | NA | NA | −42.46 (−43.74 to −41.19)*** | −65.46 | ||

| Observations | 122 264 | NA | 156 220 | NA | 127 769 | |||

| R2 | 0.019 | NA | 0.036 | NA | 0.057 | |||

NA=not applicable.

Model run with robust standard errors; deprivation fifth 1 serves as reference category for deprivation, male is reference category for sex, and under 50 years is reference category for age; model also controls for area type (city, town, hamlet and isolated dwelling, village) and provider type (private, foundation trust, teaching hospital, specialist hospital, traditional NHS); dependent variable=waiting time for hip replacement, measured in days.

*P<0.05.

**P<0.01.

***P<0.001.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients for cataract repair

| 1997-2000 | 2001-4 | 2005-7 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient (95% CI) | T statistic | β coefficient (95% CI) | T statistic | β coefficient (95% CI) | T statistic | |||

| Deprivation fifth: | ||||||||

| 2 | 3.18 (2.04 to 4.33)*** | 5.44 | 2.28 (1.54 to 3.02)*** | 6.02 | −0.57 (−0.93 to −0.20)** | −3.03 | ||

| 3 | 5.28 (4.14 to 6.43)*** | 9.05 | 3.81 (3.07 to 4.56)*** | 10.02 | 0.13 (−0.24 to 0.51) | 0.69 | ||

| 4 | 6.27 (5.11 to 7.43)*** | 10.58 | 2.56 (1.80 to 3.31)*** | 6.61 | −0.52 (−0.91 to −0.14)** | −2.7 | ||

| 5 | 3.97 (2.78 to 5.16)*** | 6.55 | −5.53 (−6.31 to −4.76)*** | −13.98 | −3.52 (−3.90 to −3.13)*** | −17.92 | ||

| Female sex | 12.75 (12.06 to 13.44)*** | 36.19 | 9.14 (8.69 to 9.60)*** | 39.59 | 3.63 (3.41 to 3.86)*** | 31.62 | ||

| Age: | ||||||||

| 50s | −2.43 (−4.26 to −0.59)* | −2.59 | −10.05 (−11.28 to −8.83*** | −16.09 | −3.70 (−4.345 to −3.06)*** | −11.28 | ||

| 60s | 14.77 (13.30 to 16.24)*** | 19.72 | 0.23 (−0.77 to 1.23) | 0.46 | −2.89 (−3.42 to −2.35)*** | −10.63 | ||

| 70s | 24.73 (23.41 to 26.06)*** | 36.64 | 8.62 (7.70 to 9.53)*** | 18.44 | −2.04 (−2.54 to −1.54)*** | −8.01 | ||

| 80s | 27.83 (26.49 to 29.18)*** | 40.54 | 14.41 (13.48 to 15.34)*** | 30.41 | 0.39 (−0.11 to 0.90) | 1.52 | ||

| Year: | ||||||||

| 1998 | 0.15 (-0.99 to 1.28) | 0.26 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 1999 | −4.15 (−6.28 to −2.02)*** | −3.84 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 2000 | −5.74 (−7.04 to −4.44)*** | −8.67 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 2002 | NA | NA | −3.39 (−4.13 to −2.64)*** | −8.90 | NA | NA | ||

| 2003 | NA | NA | −20.75 (−21.45 to −20.05)*** | −58.34 | NA | NA | ||

| 2004 | NA | NA | −75.34 (−75.97 to −74.71)*** | −234.55 | NA | NA | ||

| 2006 | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.99 (−1.27 to −0.71)*** | −6.95 | ||

| 2007 | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.80 (−1.09 to −0.51)*** | −5.46 | ||

| Observations | 703 827 | NA | 1 049 919 | NA | 814 572 | NA | ||

| R2 | 0.0250 | NA | 0.093 | NA | 0.006 | NA | ||

NA=not applicable.

Model run with robust standard errors; deprivation fifth 1 serves as reference category for deprivation, male is reference category for sex, and under 50 years is reference category for age; model also controls for area type (city, town, hamlet and isolated dwelling, village) and provider type (private, foundation trust, teaching hospital, specialist hospital, traditional NHS); dependent variable=waiting time for cataract repair, measured in days.

*P<0.05.

**P<0.01.

***P<0.001.

Discussion

Between 1997 and 2007, waiting times for elective knee replacements, hip replacements, and cataract repairs dropped significantly and equity, measured as the variation in waiting times according to socioeconomic status, improved. Waiting times and waiting lists have long been a concern in the NHS, particularly for high volume, elective surgical procedures such as knee replacements, hip replacements, and cataract repairs. However, as waiting times have dropped over the past decade, examining whether the reductions in waiting times have produced equitable results at a national level is worthwhile. Previous research has shown that greater deprivation is associated with longer waits in Scotland, and a small scale study of 4309 patients in England from April 2000 to 2001 found some inequity in the distribution of waiting times.8 9

The government’s policies to target waiting times in England can largely be broken down into three periods: one between 1997 and 2000, a second from 2001 to 2004, and a third from 2005 to 2007.5 6 8 During the 1997-2000 period, the government focused on reducing the number of patients on waiting lists (as opposed to waiting times), a modest increase in funding occurred, operational and technical support for reducing waiting lists increased, and the rhetoric of government policy shifted from an emphasis on competition to one on cooperation and collaboration. However, after two years of attempting to shorten waits, waiting times had risen, not fallen, a policy failure for which the then secretary of state for health, Frank Dobson, took personal responsibility and issued a national apology.10 The second waiting time policy period, from 2001 to 2004, saw dramatic increases in funding and the implementation of waiting time targets coupled with performance management as part of a command and control policy labelled by Bevan and Hood as “targets and terror;” it also saw the planting of the seeds of choice and competition and expanded supply as outlined in the NHS plan.11 12 13 This period of targets and centralisation was associated with reductions in waiting times in comparison with Scotland, which abandoned targets during this period.14 The final period of government policy from 2005 to 2007 centred on expanding the capacity in the system, increasing the use of providers from the private sector, and introducing greater choice for patients and competition between providers. Throughout the second half of 2004 patients waiting more than six months for care were given a choice of attending an alternative provider that had a shorter waiting time; in 2005 patients having cataract repair generally had a choice of four or more providers, and beginning in early 2006 the aim was for almost all patients to have a choice of four or more providers at their point of referral.15 16 17 This period was also associated with a continuing fall in waiting times, despite a dramatic rise in overall activity.9

Given the plethora of reforms aimed at reducing waiting times introduced between 1997 and 2007 in England, ascribing the drop in waiting times that occurred after 2000 to one policy reform rather than another is difficult. The rise in funding, the rigid government targets, and increased choice and competition are all likely to have played a role together in shortening patients’ waits. The focus of this study, however, is less on the overall reduction of waiting times and more on how the relation between deprivation and waiting times has changed over the past decade. In addition to reducing waits and improving quality, the government, along with several policy makers and advisers close to government, argued that the reforms, especially those associated with choice for patients, would be a vehicle to improve equity.16 18 19 They argued that in health services without formalised choice, some form of privilege always exists for middle class and upper class users, who use their “voice” to negotiate for better services within the publicly funded service or can afford to access care in the private sector.18 Creating formal choice in the health service, the government argued, would give all patients greater power to affect their use of resources, irrespective of their socioeconomic status, as well as providing a more efficient system for matching supply to demand. Likewise, the argument was that the market based reforms would improve allocative efficiency and drive down the long waits that were felt by poor people in particular.20

In contrast, several analysts argued that the expansion of choice for patients and competition between providers would not only not improve equity but would harm it.2 3 4 Among other lines of their argument, critics of choice and competition have argued that better off people were better equipped to choose and that the reforms would produce incentives to focus on wealthy people to the detriment of the poor. Hence, a belief existed that proponents of the government’s reforms had overlooked the possibly serious negative impact that choice and competition could have on equity.4

Although initial results from the pilot of choice in London suggested that little or no difference existed in the take up of choice by different social classes, no aggregate evidence has been available on whether the reforms have harmed or improved equity.21 Our results show that during the period after the reforms were introduced, waiting times for knee replacement, hip replacement, and cataract repair continued to fall and the variation in waiting times between fifths of deprivation was reduced. Hence, contrary to critics’ fears, by 2007 patients’ deprivation had little impact on their waiting times. In certain circumstances, by 2007 patients in more deprived areas were waiting less time than patients from less deprived areas.

Our findings do not allow us to state with confidence what policy mechanisms led to reductions in waiting times and improvements in equity. It would be inappropriate to conclude that, for instance, increased choice and competition led to improvements in equity. What we can assert with confidence, however, is that the introduction of choice and competition, as well as the other post-2000 government reforms, did not lead to the inequitable distribution of waiting times across socioeconomic groups that many people had predicted. As the government continues to emphasise the importance of choice and competition in England, these findings should be incorporated into the discussion of whether these reforms will necessarily lead to various types of inequalities.22

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the Carstairs index of deprivation is one of several ways of measuring socioeconomic status. Most of the indices are significantly correlated, but our measure is accurate only at the level of the output area.7 It therefore cannot pick up deprivation of individual patients but rather the deprivation level of the area in which the patient lives.

Secondly, as stated, given the number of policy processes happening at the same time, proving that one element of the reforms rather than another caused either the drop in waiting times or the improvement in equity is difficult. This analysis was largely a descriptive analysis, so we have been careful not to ascribe causation.

Thirdly, these data are cross sectional, and the patients’ characteristics varied from year to year depending on who was referred for care. Therefore, variation exists in our samples over time. We are unable, for instance, to determine whether patients elected to use the private sector and this loss of demand for public provision led to a decrease in waits. Although this is unlikely, it should nevertheless be taken into account. Likewise, this study looks at equity with reference to use of services not with reference to access.

Fourthly, this analysis is focused on three particular surgical procedures—knee replacement, hip replacement, and cataract repair. Together, the three procedures account for between 6% and 7% of total elective surgical activity. Although we have no reason to believe that the patterns seen for these elective procedures are unique, we have no means of knowing with certainty that waiting times for all other elective surgical procedures have followed the same trends.

Fifthly, this analysis relies on administrative data. Such data are relatively easy to acquire, encompass the whole English population, and are computer readable. However, possible shortcomings include data miscoding, missing data, and few measures of process quality. However, missing data or miscoding would be unlikely to lead to the clear, consistent, and statistically significant results that we have observed.

What is already known on this topic

Little recent evidence exists on the association between waiting times and individual patients’ socioeconomic status in England

The impact that the government’s recent reforms on equity and quality is also not well documented

What this paper adds

The reforms have not had a deleterious impact on the equity of waiting times for elective surgery in England

We thank the Dr Foster Unit at Imperial College London for processing the data. We also thank Gordon Hart for his contribution to constructing the original dataset and comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Contributions: ZNC had the original idea for the study. SJ obtained and cleaned the data. ZNC wrote the first draft of the paper and wrote subsequent drafts after feedback from the other three authors. All four authors contributed to the study design and the interpretation of the results and gave final approval. ZNC, AMcG, and JLG are the guarantors.

Funding: This research was funded through an LSE doctoral studentship and a Morris Finer PhD fellowship.

Competing interests: JLG worked part time in the Policy Directorate at No 10 Downing Street from October 2003 to June 2004 and full time from June 2004 until August 2005. He was seconded from his position at the London School of Economics and continued to receive the same salary and pension contributions as at the LSE. His roles at No 10 included assessing inequities in use of services within the NHS and discussing the possible impact on equity of the government’s reforms on choice. He also advised on the rolling-out of the government’ reform policies; the policies themselves pre-dated his appointment. The work consisted of advising the prime minister and other members of the government on health service issues, assembling research evidence as required, discussions with stakeholders, helping with the intellectual content of speeches, and working with civil servants on implementing the reforms.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3264

References

- 1.Martin R, Sterne J, Gunnell D, Ebrahim S, Smith GD, Frankel S. NHS waiting lists and evidence of national or local failure: analysis of health service data. BMJ 2003;326:188-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appleby J, Harrison A, Devlin N. What is the real cost of more patient choice? London: King’s Fund, 2003.

- 3.Oliver A, Evans J. The paradox of promoting choice in a collectivist system. J Med Ethics 2005;31:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr D, Fenton L, Blane D. The claim for patient choice and equity. J Med Ethics 2008;34:271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appleby J, Harrison A. The war on waiting for hospital treatment. London: King’s Fund, 2005.

- 6.Klein R. The troubled transformation of Britain’s National Health Service. N Engl J Med 2006;355:409-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan O, Baker A. Measuring deprivation in England and Wales using 2001 Carstairs scores. Health Stat Q 2006;(31):28-33. [PubMed]

- 8.Pell J, Pell A, Norrie J, Ford I, Cobbe S. Effect of socioeconomic deprivation on waiting time for cardiac surgery: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2000;321:15-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siciliani L, Martin S. An empirical analysis of the impact of choice on waiting times. Health Econ 2007;16:763-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waiting for Dobbo. Economist May 23 1998:51-2.

- 11.Bevan G, Hood C. Have targets improved performance in the English NHS? BMJ 2006;332:419-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Secretary of State for Health. The NHS plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Department of Health, 2000.

- 13.Stevens S. Reform strategies for the English NHS. Health Aff 2004;23(3):39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Propper C, Sutton M, Whitnal C, Windmeijer F. Did ‘targets and terror’ reduce waiting times in England for hospital care? Bristol: Centre for Market and Public Organisation, 2007. (CMPO working paper No 07/179.)

- 15.Department of Health. Implementing choice at referral for cataracts [letter to SHA choice leads and PCT choice leads]. 2004. www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4094853.pdf

- 16.Department of Health. Building on the best: choice, responsiveness and equity in the NHS. Norwich: HMSO, 2003.

- 17.Department of Health. Health reform in England: update and next steps. London: Department of Health, 2005.

- 18.Dixon A, Le Grand J. Is greater patient choice consistent with equity? The case of the English NHS. J Health Serv Res Policy 2006;11:162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens S. Equity and choice: can the NHS offer both? In: Oliver AJ, ed. Equity in health and health care: views from ethics, economics and political science proceedings from the meeting of the Healthcare Equity Network. London: Nuffield Trust, 2003.

- 20.Siciliani L, Hurst J. Tackling excessive waiting times for elective surgery: a comparative analysis of policies in 12 OECD countries. Health Policy 2005;72:201-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulter A, le Maistre N, Henderson L. Patients’ experience of choosing where to undergo surgical treatment: evaluation of the London patient choice scheme. London: Picker Institute, 2005.

- 22.Department of Health. High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. London: Department of Health, 2008.