Abstract

Background and purpose:

Sodium sulphide (Na2S) disassociates to sodium (Na+) hydrosulphide, anion (HS−) and hydrogen sulphide (H2S) in aqueous solutions. Here we have established and characterized a method to detect H2S gas in the exhaled breath of rats.

Experimental approach:

Male rats were anaesthetized with ketamine and xylazine, instrumented with intravenous (i.v.) jugular vein catheters, and a tube inserted into the trachea was connected to a pneumotach connected to a H2S gas detector. Sodium sulphide, cysteine or the natural polysulphide compound diallyl disulphide were infused intravenously while the airway was monitored for exhaled H2S real time.

Key results:

Exhaled sulphide concentration was calculated to be in the range of 0.4–11 ppm in response to i.v. infusion rates ranging between 0.3 and 1.1 mg·kg−1·min−1. When nitric oxide synthesis was inhibited with Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester the amount of H2S exhaled during i.v. infusions of sodium sulphide was significantly increased compared with that obtained with the vehicle control. An increase in circulating nitric oxide using DETA NONOate [3,3-bis(aminoethyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1-triazene] did not alter the levels of exhaled H2S during an i.v. infusion of sodium sulphide. An i.v. bolus of L-cysteine, 1 g·kg−1, and an i.v. infusion of the garlic derived natural compound diallyl disulphide, 1.8 mg·kg−1·min−1, also caused exhalation of H2S gas.

Conclusions and implications:

This method has shown that significant amounts of H2S are exhaled in rats during sodium sulphide infusions, and the amount exhaled can be modulated by various pharmacological interventions.

Keywords: sodium sulphide, hydrogen sulphide, NOS inhibition, nitric oxide, DADS, L-cysteine

Introduction

Hydrogen sulphide (H2S) is a colourless and flammable gas with the characteristic smell of rotten eggs. It dissolves well in water. Aqueous solutions of H2S are unstable as a result of the reaction of sulphide with O2. For many decades, H2S received attention as a toxic gas and as an environmental hazard (Reiffenstein et al., 1992). H2S is produced in large quantities when sulphur-containing proteinaceous materials undergo putrefaction. H2S, therefore, is also referred to as ‘swamp gas’ or ‘sewer gas’. More recent work, however, has identified H2S as a gaseous biological mediator that is produced in mammalian organisms and human bodies. H2S is synthesized endogenously by a variety of mammalian tissues by two pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent enzymes responsible for metabolism of L-cysteine, cystathionine beta-synthase and cystathionine gamma-lyase. The substrate of cystathionine beta-synthase and cystathionine gamma-lyase, L-cysteine can be derived from alimentary sources or can be liberated from endogenous proteins (Wang, 2003;Fiorucci et al., 2006; Szabo, 2007; Li and Moore, 2008).

H2S affects fundamental biological functions including life span and survival under severe hypoxic conditions (Blackstone and Roth, 2007; Miller and Roth, 2007). Recent studies have also demonstrated that in many pathophysiological conditions, intravenous (i.v.) or oral administration of various formulations or precursors of H2S are of therapeutic benefit (overviewed in Szabo et al., 2007; Wallace et al., 2007). Animal models of pathophysiological conditions where H2S has been shown to be of therapeutic benefit include myocardial infarction (Sivarajah et al., 2006; Elrod et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2007; Rossoni et al., 2008; Sodha et al., 2008), acute respiratory distress syndrome (Esechie et al., 2008), colitis (Fiorucci et al., 2007), pancreatitis (Bhatia et al., 2008) and gastric ulceration (Wallace et al., 2007).

When administered systemically, sulphide donors or precursors can convert into hydrogen sulphide gas, and this gas can be absorbed via the lung into the circulation. Hence, we have investigated the ability of intravenously administered hydrogen sulphide donors to induce exhalation of hydrogen sulphide. In our studies we have used IK-1001 (sodium sulphide for injection), a parenteral injectable GMP formulation of H2S (Szabo, 2007). This material has recently been used in many experimental studies to characterize the pharmacological effects of H2S in vitro and in vivo (Elrod et al., 2007; Jha et al., 2008; Kiss et al., 2008; Simon et al., 2008; Sodha et al., 2008). In order to pharmacologically explore the contribution of the arterial and venous vascular beds to the clearance of hydrogen sulphide, we have also compared the effect of intra-arterial versus i.v. injection of IK-1001 on the amount of exhaled H2S gas. We also investigated the relationship between sulphide and nitric oxide (NO) by determining whether inhibition of NO synthase or donation of NO affects the exhalation of H2S gas during an i.v. infusion of sodium sulphide. Finally, we investigated whether administration of cysteine, the precursor of hydrogen sulphide biosynthesis, or diallyl disulphide (DADS), a garlic-derived natural polysulphide compound, produces a detectable change in the concentration of hydrogen sulphide exhaled.

Methods

Detection of exhaled hydrogen sulphide (H2S)

A RM17-5.0m or RM17-1000b hydrogen sulphide detector was used to monitor levels of H2S. The RM17-5.0m detector has a high range of 5 parts per million (ppm), and the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) is 1% of full range, which is 0.05 ppm [or 50 ppb (parts per billion)]. The range for the RM17-1000b is 10–1000 ppb. The detector's analogue outputs will produce 0 mV with no H2S present and 100 mV with 5 ppm or 1000 ppb present with a linear response respectively. A PowerLab16/30 was used to convert the mV signal into ppm or ppb and display the levels in real time. To determine the response time of the sensor a 5 ppm calibration gas was connected to through a side port of the pneumotach, and the response was recorded for over 5 min.

Animal model of IK-1001 administration

Male Sprague Dawley or CD-1 IGS rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA) weighing 250–300 g with indwelling jugular vein catheters were given an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of a ketamine/xylazine mixture (72 mg·kg−1 ketamine, 23 mg·kg−1 xylazine) and once under a surgical plane of anaesthesia were intubated and placed on a warming pad. The intubation tube was connected to a Model 8420B heated pneumotach, coupled to a spirometer (model ML141) to measure airway flow; respiratory rate was calculated from this as well. A side port of the pneumotach was connected to the H2S detector and expired air was sampled continuously at a rate of 500 mL·min−1. A bioamp (model ML132) and three needle electrodes were used to monitor EKG, and heart rate (HR) was calculated from the EKG trace. A PowerLab was used for all data collection, and the following parameters were all measured in real time: H2S concentration (ppm or ppb), airway flow (mL·s−1), tidal volume (mL), respiratory rate (bpm) and HR (bpm). IK-1001 was administered by using an infusion pump at rates of 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 0.9 and 1.1 mg·kg−1·min−1 (n = 5 per cohort). Each infusion lasted for 5 min.

To determine if pre-administration of a NO inhibitor, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) or NO donor 3,3-bis(aminoethyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1-triazene, DETA NONOate (DETA) affected the levels of exhaled hydrogen sulphide a 10 mg·kg−1 i.v. bolus of L-NAME, 4 mg·kg−1 i.v. bolus of DETA or vehicle was given prior to administration of IK-1001 at infusion rates of 0.4 and 0.6 mg·kg−1·min−1 (n = 5 per cohort).

To determine if cysteine would cause an exhalation of H2S gas, L-cysteine was given as an i.v. bolus at 1 g·kg−1 (n = 5). A bolus was chosen instead of an infusion because the i.v. LD50 of cysteine in a rat is 1.140 g·kg−1 (MSDS; Sigma-Aldrich, 2006).

To evaluate the effect of the garlic-derived natural compound DADS on exhaled sulphide levels, an i.v. infusion of 1.8 mg·kg−1·min−1 was administered for 3 min, and exhaled H2S was monitored as described above (n = 5).

Animal model of haemodynamic evaluation

Inhibitors of NO synthesis (L-NAME) and NO donors (DETA) can affect haemodynamics, and a change in mean arterial pressure (MAP) or pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) may affect the amount of exhaled H2S. We measured the effect of a 10 mg·kg−1 i.v. bolus of L-NAME or 4 mg·kg−1 i.v. bolus of DETA on baseline levels of MAP as well as PAP. Furthermore any changes that occurred when a 0.4 mg·kg−1·min−1 i.v. infusion of IK-1001 was administered to these L-NAME- or DETA-pretreated animals was monitored. MAP was measured in ketamine/xylazine-anaesthetized rats by using a fluid-filled catheter inserted into the carotid artery. PAP was measured in anaesthetized rats that were mechanically ventilated with a rodent ventilator (model 683). The chest was opened, and a solid phase Mikro-Tip catheter was inserted into the heart, through the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery.

Calculation of exhaled H2S

The Data Pad function of Chart 5 Pro (v5.5.5) was used to calculate the total volume of air, total ppm of H2S gas collected based on the integrals of the flow recording and H2S recording respectively. Data collection for analysis started at least 2 min after the infusion started taking into consideration the sensor response time. The sampling rate of the detector (500 mL·min−1) greatly exceeded the minute respiration of the rats, and after correcting for this sample dilution the average concentration of sulphide exhaled per breath was calculated.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as mean ± SEM with n representing the number of experimental observations per cohort. Statistical analysis was performed by using an unpaired t-test with GraphPad Prism Version 5.00 statistical software. Probability values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Materials

Hydrogen sulphide detector, Interscan (Chatsworth, CA, USA); PowerLab16/30, spirometer, bioamp and Chart 5 Pro (v5.5.5), ADInstruments (Colorado Springs, CO, USA); calibration gas, MESA Specialty Gases & Equipment (Santa Ana, CA, USA); heated pneumotach, Hans Rudolph (Shawnee, KS, USA); infusion pump and rodent ventilator, Harvard Apparatus (Holliston, MA, USA); Mikro-Tip catheter, Millar Instruments (Houston, TX, USA).

L-NAME, DETA and L-cysteine, Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA); DADS, LKT Laboratories (St. Paul, MN, USA).

Results

H2S sensor response

The instrument records near maximum value (>95%) within the 90 s of gas exposure at which point a steady state is reached. Following the end of gas flow, the decline in H2S levels are rapid, values were less than 5% of maximum value (0.250 ppm) within 1 min. In order to obtain an accurate reading of the H2S concentration, we monitored exhaled gas concentrations for at least 2 min.

Effect of an i.v. infusion of IK-1001 on exhalation of H2S gas

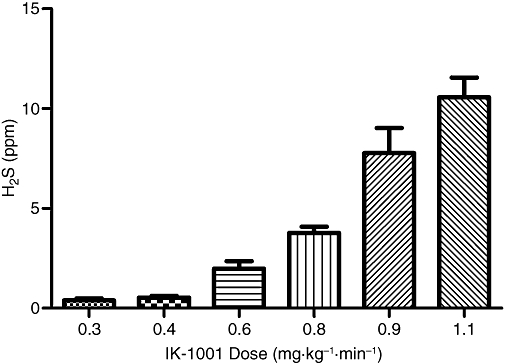

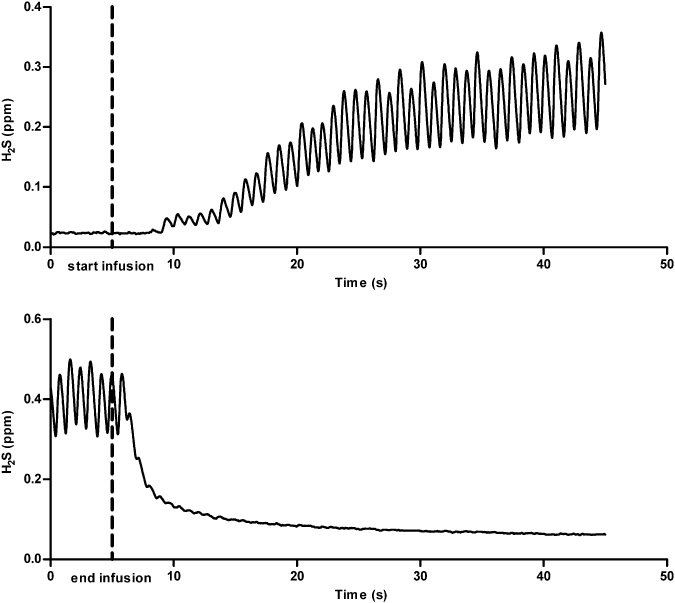

Intravenous infusions of IK-1001 at rates between 0.3 and 1.1 mg·kg−1·min−1 caused a dose-dependent exhalation of H2S (Figure 1). The lowest dose tested, 0.2 mg·kg−1·min−1, did not elevate H2S above the 50 ppb LLOQ. Infusion rates between 0.8 and 0.9 mg·kg−1·min−1 caused some transient physiological changes: slight increases in HR, and a significant elevation of respiratory rate for the 0.9 mg·kg−1·min−1 cohort (P < 0.05), which resolved when the infusion ended, while infusion rates of 1.1 mg·kg−1·min−1 caused similar but more severe reactions (Table 1). Within seconds following the start of IK-1001 administration, H2S levels became detectable and after approximately 1–2 min the amount of exhaled H2S reached a steady state. The drop in H2S exhalation following the end of the infusion was immediate (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

H2S exhaled (per breath) during a 5 min i.v. infusion of IK-1001. Values are mean ± SEM; n = 5 per cohort.

Table 1.

Animal physiology recordings during i.v. administration of IK-1001

| IK-1001 dose (mg·kg−1·min−1) | Average H2S exhaled (ppm) | Tidal volume (mL) | Maximum airway flow (mL·s−1) | Heart rate (bpm) | Respiratory rate (bpm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 | 0.40 ± 0.10 | 1.34 ± 0.19 | 10.14 ± 0.39 | 245 ± 8 | 66 ± 5 |

| 0.4 | 0.54 ± 0.09 | 1.56 ± 0.13 | 10.32 ± 0.73 | 244 ± 6 | 83 ± 7 |

| 0.6 | 1.98 ± 0.38 | 1.40 ± 0.20 | 10.33 ± 0.41 | 247 ± 7 | 70 ± 5 |

| 0.8 | 3.77 ± 0.31 | 1.77 ± 0.11 | 10.08 ± 0.85 | 248 ± 8 | 94 ± 4 |

| 0.9 | 7.77 ± 1.26 | 1.99 ± 0.34 | 9.79 ± 0.40 | 247 ± 6 | 101 ± 13 |

| 1.1 | 10.57 ± 0.99 | 1.94 ± 0.13 | 9.48 ± 0.62 | 263 ± 14 | 102 ± 7 |

Animals receiving IK-1001 (0.9 and 1.1 mg·kg−1·min−1) had a significant increase (P < 0.05) in respiratory rate compared with the lowest dose cohort. Values are mean ± SEM; n = 5 per cohort.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the original Chart recordings indicating that H2S exhalation begins immediately following the start of an infusion of IK-1001 and declines rapidly following the end of the infusion. The infusion rate of IK-1001 for this rat was 0.6 mg·kg−1·min−1. Each peak indicates a breath.

Effect of intra-arterial infusion of IK-1001 on exhalation of H2S gas

When IK-1001 was given intra-arterialy (i.a.), exhaled H2S gas was detected, but at levels much lower than that was observed with i.v. infusions at the same rates. No H2S was detected at 0.2 mg·kg−1·min−1, and only one animal out of four at 0.3 or 0.4 mg·kg−1·min−1 produced H2S above the LLOQ (data not shown).

Effect of L-NAME or DETA pretreatment on the exhalation of H2S gas in response to i.v. infusions of IK-1001

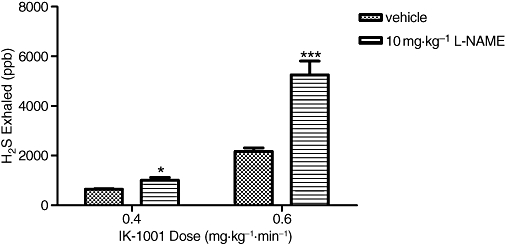

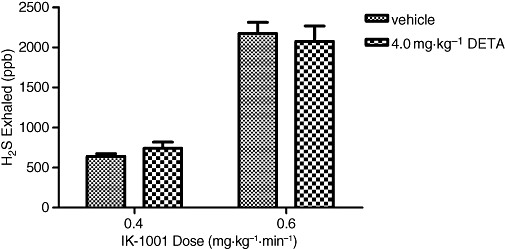

Intravenous infusions of IK-1001 at 0.4 and 0.6 mg·kg−1·min−1, in vehicle-, L-NAME- and DETA-pretreated animals caused a dose-dependent exhalation of hydrogen sulphide. The concentration of H2S exhaled in animals pretreated with 10 mg·kg−1 L-NAME was significantly elevated for both the 0.4 mg·kg−1·min−1 cohort (P < 0.05 vs. vehicle) and 0.6 mg·kg−1·min−1 cohort (P < 0.001 vs. vehicle) (Figure 3), while the concentration of H2S exhaled in DETA-pretreated animals was similar to that in the vehicle-pretreated animals (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

H2S exhaled (per breath) during an i.v. infusion of IK-1001 at rates of 0.4 or 0.6 mg·kg−1·min−1 in animals pretreated with an i.v. bolus of 10 mg·kg−1 L-NAME (Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester). Values are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus vehicle, ***P < 0.001 versus vehicle; n = 5 per cohort.

Figure 4.

H2S exhaled (per breath) during an i.v. infusion of IK-1001 at rates of 0.4 or 0.6 mg·kg−1·min−1 in animals pretreated with an i.v. bolus of 4 mg·kg−1 DETA (3,3-bis(aminoethyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1-triazene). Values are mean ± SEM; n = 5 per cohort.

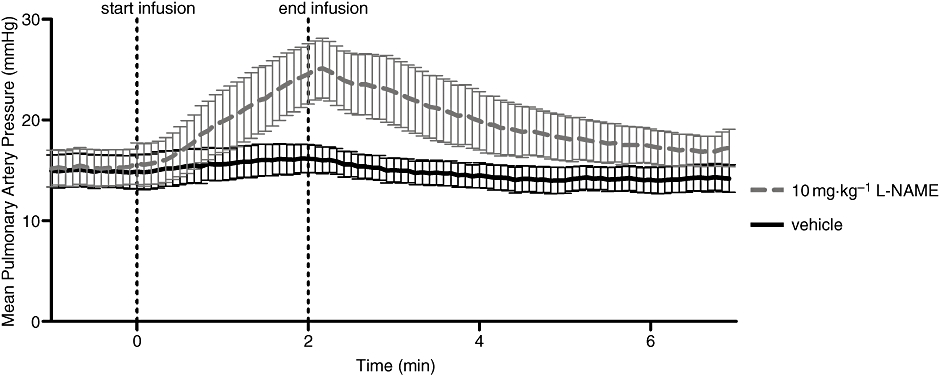

Haemodynamic changes following L-NAME or DETA pretreatment

A 10 mg·kg−1 i.v. bolus of L-NAME elevated MAP from 120 ± 16 to 152 ± 10 mmHg (P < 0.01), while PAP and HR did not significantly change. A 4 mg·kg−1 i.v. bolus of DETA decreased MAP from 124 ± 7 to 87 ± 5 mmHg, PAP and HR did not significantly change. A 2 min infusion of IK-1001 at 0.4 mg·kg−1·min−1, started within 5 min of either L-NAME or DETA pretreatment, did not significantly alter MAP or HR; however, there was a significant increase (P < 0.05) in PAP from 15 ± 2 to 25 ± 3 mmHg (at the end of the infusion) in animals pretreated with L-NAME (Figure 5), but no change in PAP in DETA-pretreated animals.

Figure 5.

Mean pulmonary artery pressure in rats pretreated with 10 mg·kg−1 L-NAME (Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester) or vehicle, before, during and following an infusion of IK-1001, 0.4 mg·kg−1·min−1. The start and end lines indicate the beginning and end of the infusion of IK-1001. Values are mean ± SEM; n = 5 per cohort.

Effect of L-cysteine administration on exhalation of H2S gas

When L-cysteine was given as an i.v. bolus at a dose of 1 g·kg−1, exhalation of H2S was observed, and the pattern of exhalation was a gradual rise and fall that persisted over a 3–5 min period, the highest level exhaled per breath was 0.89 ± 0.34 ppm H2S.

Effect of the garlic-derived natural polysulphide compound, diallyl disulphide on exhalation of H2S gas

The exhalation of hydrogen sulphide gradually rose throughout the 1.8 mg·kg−1·min−1 3 min infusion of DADS and reached a maximum level of 0.23 ± 0.03 ppm per breath at the end of the infusion. The levels of exhaled H2S started to decline immediately following the end of the infusion.

Discussion

It is known that an i.v. bolus injection of sodium bicarbonate induces a transient increase in PaCO2 and end tidal CO2 (Fanconi et al., 1993; Okamoto et al., 1994). Bicarbonate (HCO3−) is in equilibrium with dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2). Under acidic conditions sodium sulphide (Na2S) would dissociate to the sodium (Na+) and the hydrosulphide anion (HS−), which then forms hydrogen sulphide gas. Initially we observed that when low doses of IK-1001 were administered to large animals we could smell H2S emanating from the animals' nose (E.A. Wintner and C. Szabo, unpubl. obs.). The estimated odour threshold of H2S for humans is in the range of 3–20 ppb (Glass, 1990; Reiffenstein et al., 1992; Hirsch and Zavala, 1999). To further characterize this finding we bubbled expired air from a rat, which had been given an i.v. bolus of IK-1001, into sulphide antioxidant buffer and detected H2S concentrations in the buffer using a silver/sulphide electrode. This confirmed that sulphide was being exhaled following an i.v. bolus of IK-1001 (M.A. Insko, P. Hill and C.T. Toombs, unpubl. obs.). Because of these observations, we set up the present experimental system to systematically measure and quantify exhaled H2S concentrations in the rodent. The lower limit of detection is approximately 10–50 ppb (depending on the sensor), which provided sufficient sensitivity to conduct the current studies. We postulate that appropriate modifications of the present system may provide a method for monitoring exhaled sulphide levels in humans in health and disease, as well as before, during and after the administration of therapeutic sulphide-releasing or sulphide-containing compounds.

Components of the oral bacterial flora can produce H2S, and this gas has been characterized as a potential contributor to halitosis (oral malodour) (e.g. Washio et al., 2005). Studies of hydrogen sulphide toxicology indicate that exposure to high doses of hydrogen sulphide may or may not contribute to exhalation of H2S gas. For instance, when sodium sulphide at 0.1, 0.25 and 0.32 mmol·kg−1 body weight was administered intraperitoneally to mice, no exhaled sulphide was detected (Susman et al., 1978). Petrun (1966) observed that when the skin of rabbits was exposed to hydrogen sulphide at concentrations of 700 and 1400 ppm, trace amounts of hydrogen sulphide were found in the exhaled air of the rabbits. No quantitative information was given in these reports. Based on case reports, in environmental documents it is frequently stated that exhaled H2S can be detected in victims of H2S gas exposure (Strickland et al., 2003). More relevant from a pharmacological and experimental therapeutic standpoint are the studies of Morselli-Labate et al. (2007), who observed that an increase in exhaled H2S can be measured in the exhaled breath of patients with chronic pancreatitis. In the current study we have demonstrated that i.v. administration of sodium sulphide results in a significant and dose-dependent increase in exhaled hydrogen sulphide gas. Interestingly, the doses of IK-1001 resulting in hydrogen sulphide being detected in the exhaled air are in the same range (0.3–1 mg·kg−1) as those previously demonstrated to be therapeutically effective in a variety of animal models of disease (overviewed in Szabo, 2007). It was not surprising to note that the fraction exhaled during an arterial infusion was lower than with an i.v. infusion. With an arterial infusion, IK-1001 would travel systemically through remote capillary beds before coming to the lungs and being exhaled, while an i.v. infusion of IK-1001 would encounter the lungs first. The pattern of H2S gas expired is also different between the i.v. and the i.a. infusions. When given i.v. it may reach a steady state much more quickly than when given i.a., which may indicate a rapid half-life of IK-1001 and that it is degraded in the systemic circulation before arriving at the lungs. The duration of exhaled H2S observed in the current studies is short, as evidenced by the rapid return of exhaled H2S levels to baseline after discontinuation of parenteral IK-1001 administration. This observation is consistent with short half-life of hydrogen sulphide in vivo (Reiffenstein et al., 1992; Whitfield et al., 2008; Bengtsson et al., 2008).

As various interactions and crosstalks between the NO and hydrogen sulphide pathway have been postulated (Ali et al., 2006; Whiteman et al., 2006), we examined whether pharmacological inhibition of NO biosynthesis with L-NAME affects the levels of exhaled H2S gas in our experimental set-up. The dose of L-NAME used has previously been shown to induce significant increases in mean arterial blood pressure due to inhibition of tonic NO production and to reduce blood flow to various organs (Gardiner et al., 1990; Van Gelderen et al., 1991). Our results clearly demonstrate that after pretreatment with L-NAME the amount of exhaled H2S gas increases. There may be several reasons for this effect, including an effect related to changes in pulmonary artery pressure. Indeed, our direct measurements demonstrated that after L-NAME pretreatment (but not in the absence of L-NAME), sodium sulphide infusion produces a significant increase in PAP. Hence, it is possible that this effect may alter the amount of sulphide exhaled via the lung. Another possibility is that NO interacts with the H2S: several studies have demonstrated that NO and H2S react with each other and form a relatively stable nitrosothiol compound (Whiteman et al., 2006). It is conceivable, therefore, that when endogenous NO synthesis is inhibited, this ‘buffering’ capacity of NO is diminished, and therefore an increase in biologically available H2S is present, which, in turn, produces more H2S in the exhaled air. Interestingly, while inhibition of endogenous NO synthesis enhanced the amount of exhaled hydrogen sulphide, infusion of excess NO did not affect the amount of exhaled hydrogen sulphide, possibly indicating that the availability of NO is not the rate-limiting step in this reaction. Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact mechanism of the NO/hydrogen sulphide interaction. It is well established that endogenous NO biosynthesis is diminished in a variety of pathophysiological conditions including atherosclerosis and diabetes (Ignarro, 2000; Liaudet et al., 2000; Soriano et al., 2001). Furthermore, increased oxidative stress (which is also a common feature of many cardiovascular diseases) (Pacher et al., 2007; Szabo et al., 2007) can also enhance the degradation of biologically active sulphide (Whiteman et al., 2004; Mitsuhashi et al., 2005). Hence, it would be of interest to evaluate whether biological availability of H2S and/or the amount of exhaled H2S gas is altered in these pathophysiological states.

Cysteine is an endogenous precursor of H2S biosynthesis. Although cysteine is probably not the rate-limiting factor in the biosynthesis of H2S, it has been shown, in vitro, that administration of cysteine to cells in culture can produce biological responses that are consistent with increased H2S biosynthesis (Yang et al., 2005). Here we tested whether a high dose of intravenously administered cysteine can induce a detectable amount of exhaled H2S in the rat. Cysteine (1 g·kg−1) produced a detectable amount of H2S (approximately 1 ppm). However, this amount is relatively small; the amount of exhaled H2S in response to 1 g·kg−1 cysteine was approximately 10 times lower than the amount of exhaled H2S in response to 1.1 mg·kg−1 sodium sulphide. Given the molecular weights of cysteine and sodium sulphide (121 and 78 respectively), we estimated that on a molar basis, conversion of cysteine to H2S gas is approximately 600 times less efficient than H2S gas release after an intravenous sodium sulphide dose.

Recent studies by Kraus et al. have established that certain natural garlic-derived polysulphides react with glutathione in vitro and in vivo and yield hydrogen sulphide. This H2S has been attributed to importantly contribute to the vascular effects of garlic (Benavides et al., 2007). Subsequent studies have attributed some of the cardiovascular protective effects of garlic extracts or garlic components to the production of H2S in vivo (Chuah et al., 2007; Shaik et al., 2008). In the present study, we demonstrated that H2S is eliminated through the lungs after administration of a typical garlic-derived polysulphide compound DADS, thereby directly demonstrating the formation of H2S in vivo in animals subjected to DADS.

In summary, the main conclusions from our results are: (i) significant amounts of exhaled H2S can be measured in response to intravenously administered sodium sulphide; (ii) the amount of H2S exhaled is significantly increased when endogenous NO synthesis is inhibited by the NO synthase inhibitor L-NAME; (iii) the amount of exhaled H2S is unaffected when endogenous NO levels are enhanced by the infusion of a NONOate compound; (iv) the amino acid precursor of endogenous H2S biosynthesis induces a slight increase in the concentration of exhaled H2S; and (v) the endogenous polysulphide DADS increases the amount of H2S exhaled. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanisms of the regulation of exhaled H2S induced by biological and pharmacological factors in health and disease. The effect of changes in the function and expression of sulphide-detoxifying enzymes (Ramasamy et al., 2006) on the biological activity and amount of exhaled H2S in health and disease needs to be explored. Given the fact that the endogenous production of H2S can be altered in various pathophysiological conditions (e.g. up-regulation of H2S producing enzymes can occur in various forms of inflammation: Tamizhselvi et al., 2007), it would be interesting to evaluate the possibility of using exhaled H2S as a diagnostic measurement.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- DADS

diallyl disulphide

- DETA

3,3-bis(aminoethyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1-triazene (DETA NONOate)

- HR

heart rate

- L-NAME

Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- PAP

pulmonary arterial pressure

Conflicts of interest

All authors of this article are employees and stockholders of Ikaria Inc., a for-profit organization involved in the commercialization of hydrogen sulphide as a human therapeutic agent.

References

- Ali MY, Ping CY, Mok YY, Ling L, Whiteman M, Bhatia M, et al. Regulation of vascular nitric oxide in vitro and in vivo; a new role for endogenous hydrogen sulphide? Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149(6):625–634. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides GA, Squadrito GL, Mills RW, Patel HD, Isbell TS, Patel RP, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(46):17977–17982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson A, Johnson J, Hill P, Mulligan J, Leviten D, Insko M, et al. Use of mono-bromo-bimane to derivatize sulfide in whole blood: comparison of blood sulfide levels during atmospheric hydrogen sulfide exposure and intravenous sulfide infusion. Experimental Biology Meeting Abstracts, Abstract #749.15.

- Bhatia M, Sidhapuriwala JN, Sparatore A, Moore PK. Treatment with H2S-releasing diclofenac protects mice against acute pancreatitis-associated lung injury. Shock. 2008;29(1):84–88. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31806ec26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone E, Roth MB. Suspended animation-like state protects mice from lethal hypoxia. Shock. 2007;27(4):370–372. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31802e27a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuah SC, Moore PK, Zhu YZ. S-allylcysteine mediates cardioprotection in an acute myocardial infarction rat model via a hydrogen sulfide-mediated pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(5):H2693–H2701. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00853.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(39):15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esechie A, Kiss L, Olah G, Horvath EM, Hawkins HK, Szabo C, et al. Protective effect of hydrogen sulfide in a murine model of combined burn and smoke inhalation-induced acute lung injury. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;115(3):91–97. doi: 10.1042/CS20080021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanconi S, Burger R, Ghelfi D, Uehlinger J, Arbenz U. Hemodynamic effects of sodium bicarbonate in critically ill neonates. Intensive Care Med. 1993;19(2):65–69. doi: 10.1007/BF01708362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Distrutti E, Cirino G, Wallace JL. The emerging roles of hydrogen sulfide in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(1):259–271. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Orlandi S, Mencarelli A, Caliendo G, Santagada V, Distrutti E, et al. Enhanced activity of a hydrogen sulphide-releasing derivative of mesalamine (ATB-429) in a mouse model of colitis. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150(8):996–1002. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner SM, Compton AM, Bennett T, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Regional haemodynamic changes during oral ingestion of NG-monomethyl-L-arginine or NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester in conscious Brattleboro rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;101(1):10–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DC. A review of the health effects of hydrogen sulphide exposure. Ann Occup Hyg. 1990;34(3):323–327. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/34.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch AR, Zavala G. Long-term effects on the olfactory system of exposure to hydrogen sulphide. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56(4):284–287. doi: 10.1136/oem.56.4.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignarro LJ. The unique role of nitric oxide as a signaling molecule in the cardiovascular system. Ital Heart J. 2000;1(Suppl. 3):S28–S29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha S, Calvert JW, Duranski MR, Ramachandran A, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of antioxidant and antiapoptotic signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(2):H801–H806. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00377.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss L, Deitch EA, Szabó C. Hydrogen sulfide decreases adenosine triphosphate levels in aortic rings and leads to vasorelaxation via metabolic inhibition. Life Sci. 2008;83(17–18):589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Moore PK. Putative biological roles of hydrogen sulfide in health and disease: a breath of not so fresh air? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(2):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaudet L, Soriano FG, Szabo C. Biology of nitric oxide signaling. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(4 Suppl.):N37–N52. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DL, Roth MB. Hydrogen sulfide increases thermotolerance and lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(51):20618–20622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710191104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi H, Yamashita S, Ikeuchi H, Kuroiwa T, Kaneko Y, Hiromura K, et al. Oxidative stress-dependent conversion of hydrogen sulfide to sulfite by activated neutrophils. Shock. 2005;24(6):529–534. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000183393.83272.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morselli-Labate AM, Fantini L, Pezzilli R. Hydrogen sulfide, nitric oxide and a molecular mass 66 u substance in the exhaled breath of chronic pancreatitis patients. Pancreatology. 2007;7(5–6):497–504. doi: 10.1159/000108967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Kishi H, Choi H, Kurose M, Sato T, Morioka T. Relationship between cardiac output and mixed venous-arterial PCO2 gradient in sodium bicarbonate-treated dogs. J Anesth. 1994;8:204–207. doi: 10.1007/BF02514714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(1):315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrun NM. Penetration of hydrogen sulfide through skin and its influence on gaseous exchange and energy metabolism. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2nd. pp. 247–250. edn, Kiev, Publishing House ‘Health’ (‘Zdoroviein’), pp. in Russian.

- Ramasamy S, Singh S, Taniere P, Langman MJ, Eggo MC. Sulfide-detoxifying enzymes in the human colon are decreased in cancer and upregulated in differentiation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291(2):G288–G296. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00324.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiffenstein RJ, Hulbert WC, Roth SH. Toxicology of hydrogen sulfide. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;32:109–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossoni G, Sparatore A, Tazzari V, Manfredi B, Del Soldato P, Berti F. The hydrogen sulphide-releasing derivative of diclofenac protects against ischaemia-reperfusion injury in the isolated rabbit heart. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(1):100–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik IH, George JM, Thekkumkara TJ, Mehvar R. Protective effects of diallyl sulfide, a garlic constituent, on the warm hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in a rat model. Pharm Res. 2008;25(10):2231–2242. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigma-Aldrich. MSDS for L(+) Cysteine, CAS # 52-90-4, version 1.5.

- Simon F, Giudici R, Duy CN, Schelzig H, Oter S, Groger M, et al. Hemodynamic and metabolic effects of hydrogen sulfide during porcine ischemia/reperfusion injury. Shock. 2008;30(4):359–364. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181674185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivarajah A, McDonald MC, Thiemermann C. The production of hydrogen sulfide limits myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury and contributes to the cardioprotective effects of preconditioning with endotoxin, but not ischemia in the rat. Shock. 2006;26(2):154–161. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000225722.56681.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodha NR, Clements RT, Feng J, Liu Y, Bianchi C, Horvath EM, et al. The effects of therapeutic sulfide on myocardial apoptosis in response to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33(5):906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano FG, Virag L, Szabo C. Diabetic endothelial dysfunction: role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species production and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation. J Mol Med. 2001;79(8):437–448. doi: 10.1007/s001090100236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susman JL, Hornig JF, Thomae SC, Smith RP. Pulmonary excretion of hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol, dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl disulfide in mice. Drug Chem Toxicol. 1978;1(4):327–338. doi: 10.3109/01480547809016045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(11):917–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C, Ischiropoulos H, Radi R. Peroxynitrite: biochemistry, pathophysiology and development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(8):662–680. doi: 10.1038/nrd2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamizhselvi R, Moore PK, Bhatia M. Hydrogen sulfide acts as a mediator of inflammation in acute pancreatitis: in vitro studies using isolated mouse pancreatic acinar cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11(2):315–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelderen E, Heiligers JP, Saxena PR. Haemodynamic changes and acetylcholine-induced hypotensive responses after NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester in rats and cats. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103(4):1899–1904. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL, Dicay M, McKnight W, Martin GR. Hydrogen sulfide enhances ulcer healing in rats. FASEB J. 2007;21(14):4070–4076. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8669com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. The gasotransmitter role of hydrogen sulfide. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5(4):493–501. doi: 10.1089/152308603768295249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio J, Sato T, Koseki T, Takahashi N. Hydrogen sulfide-producing bacteria in tongue biofilm and their relationship with oral malodour. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54(9):889–895. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46118-0. Pt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman M, Armstrong JS, Chu SH, Jia-Ling S, Wong BS, Cheung NS, et al. The novel neuromodulator hydrogen sulfide: an endogenous peroxynitrite ‘scavenger’? J Neurochem. 2004;90(3):765–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman M, Li L, Kostetski I, Chu SH, Siau JL, Bhatia M, et al. Evidence for the formation of a novel nitrosothiol from the gaseous mediators nitric oxide and hydrogen sulphide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343(1):303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield NL, Kreimier EL, Verdial FC, Skovgaard N, Olson KR. Reappraisal of H2S/sulfide concentration in vertebrate blood and its potential significance in ischemic preconditioning and vascular signaling. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(6):R1930–R1937. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Yang G, Jia X, Wu L, Wang R. Activation of KATP channels by H2S in rat insulin-secreting cells and the underlying mechanisms. J Physiol. 2005;569(2):519–531. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.097642. Pt. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YZ, Wang ZJ, Ho P, Loke YY, Zhu YC, Huang SH, et al. Hydrogen sulfide and its possible roles in myocardial ischemia in experimental rats. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(1):261–268. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00096.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]