Abstract

Modulation of voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channel surface expression can profoundly affect neuronal excitability. Some but not all mammalian Shaker or Kv1 α subunits contain a dominant endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signal in their pore region, preventing surface expression of Kv1.1 homotetrameric channels, and of heteromeric Kv1 channels containing more than one Kv1.1 subunit. The critical amino acid residues within this ER pore-region retention signal are also critical for high-affinity binding of snake dendrotoxins (DTX). This suggests that ER retention may be mediated by an ER protein with a domain structurally similar to that of DTX. One facet of such a model is that expression of soluble DTX in the ER lumen should compete for binding to the retention protein and allow for surface expression of retained Kv1.1. Here we show that luminal DTX expression dramatically increased both the level of cell surface Kv1.1 immunofluorescence staining and the proportion of Kv1.1 with processed N-linked oligosaccharides. Electrophysiological analyses showed that luminal DTX expression led to significant increases in Kv1.1 currents. Together these data showed that luminal DTX expression increases surface expression of functional Kv1.1 homotetrameric channels, and support a model whereby a DTX-like ER protein regulates abundance of cell surface Kv1 channels.

Keywords: potassium channel, neuron, endoplasmic reticulum

Introduction

Voltage-dependent K+ (Kv) channels are potent modulators of excitatory events such as action potentials, excitatory synaptic potentials, and Ca2+ influx (1). Aberrant expression, localization and function of Kv channels results in channel-based pathophysiologies or channelopathies (2, 3). Kv1 or Shaker Kv channels play a critical role in regulating excitability of mammalians axons and nerve terminals (1) and a knockout mouse lacking Kv1.1 exhibits severe epilepsy (4). Kv1 channels are large membrane protein complexes, composed of four pore-forming and voltage-sensing transmembrane α subunits and up to four cytoplasmic auxiliary Kvβ subunits (5, 6). Studies in heterologous expression systems have shown that Kv1 α subunits and Kvβ subunits can assemble promiscuously into homo-and heterotetrameric complexes (5, 7). Channels formed by different combinations of six different Kv1 α and three Kvβ subunits expressed in mammalian brain exhibit distinct biophysical and pharmacological characteristics, generating a large diversity of Kv channels (8, 9). However, native Kv1 channels purified from mammalian brain exhibit less than the expected diversity in subunit composition; strikingly absent are channels formed as homotetramers of Kv1.1 α subunits (10, 11). Altering the subunit composition of brain Kv1 channels, as occurs in Kv1.1-knockout mice, leads to neuronal dysfunction, in this case axonal hyperexcitability, enhanced excitatory synaptic neurotransmission, postsynaptic action potential discharge, and epilepsy (12).

A number of mechanisms exist to shape the α subunit composition of plasma membrane Kv1 channels. The primary determinant is a potent ER retention signal comprising residues in the ER luminal/extracellular domain of Kv1 α subunits, specifically in the extended turret adjacent to the external opening of the channel pore (13, 14). This signal contains four critical amino acid residues within the turret/pore region, which for strongly-retained Kv1.1 are A352, E353, S369 and Y379 (13, 15, 16). Three of these residues (A352, E353, and Y379) also determine high-affinity binding of the mamba snake neurotoxin dendrotoxin (DTX; (17-19). Moreover, Kv1 family members that bind DTX (Kv1.1, Kv1.2, and Kv1.6) exhibit a strong degree of ER retention relative to those that do not (Kv1.3, Kv1.4, and Kv1.5; (8, 13, 20, 21). Together, these observations suggested that the relative efficiency of ER export among Kv1 channels of different subunit composition may be mediated by a resident ER protein that binds to the turret domain of Kv1.1 in a fashion similar to DTX binding (11). One tenet of this model is that expression of soluble DTX in the ER lumen should compete for binding with the putative ER protein involved in retention of Kv1 channels with particular subunit composition and allow for their cell surface expression. Here we directly test this model by determining effects of luminal DTX coexpression on expression and function of Kv1.1 channels.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal (Kv1.2e, Kv4.2C), mouse monoclonal anti-Kv1.1 (K20/78), anti-Kv1.2 (Kv14/16), anti-Kv1.4 (K13/31) and anti-PSD95 (K28/43) have been described previously (21-24). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against ectodomains of Kv α subunits, anti-Kv4.2 (K57/1), anti-Kv1.1 (K36/15) have also been described previously (21, 24). These monoclonal antibodies are available from NeuroMab (www.neuromab.org). Anti-myc monoclonal antibody (19E10) was produced from hybridoma cells purchased from American Type Culture Collection.

Construction of DTXk in a mammalian expression vector, generation of DTXk and Kv1.1 mutants

DTXk cloned into expression vector pMAL-p2x was generously provided by Dr. Leonard A. Smith. After constructing a Sfi I restriction enzyme site at the 3′ end of DTXk, DTXk was cleaved by restriction endonucleases Sfi I and Hind III, gel purified and ligated into the mammalian expression vector pSecTAG2C following the Ig Kappa chain leader sequence (Invitrogen). DTXk and Kv1.1 point mutants were generated by Quick Change (Stratagene) PCR mutagenesis using oligonucleotide primers as described previously (13, 25).

Immunofluorescence Analysis of transfected COS-1, HEK 293 and astrocyte cells

COS-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 50 units/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin (both from Invitrogen). HEK 293 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 50 units/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin and GlutaMAX (Invitrogen). Astrocytes were prepared from cortices of newborn rat pups (P1 or P2) as described (26). Dissected cortical hemispheres were briefly incubated with 0.25% trypsin in Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+ for 20 min at 37 °C. DNAse I (Worthington) was added to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. Cells were resuspended in 10 ml of MEM containing 10% (v/v) donor horse serum, 0.6% (w/v) glucose, and 1 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin, then plated. All cells were maintained in plastic tissue culture dishes or on poly-L-lysine-coated glass coverslips in plastic Petri dishes in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with mammalian expression vectors for various rat Kv channel α subunit polypeptides by LipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen) using the manufacturer's protocol. All transfections were normalized with the same amount of cDNAs per dishes. Cells were seeded at 40% confluence (for biochemical analysis) or 5 % confluence (for immunofluorescence).

Cells were stained 48 h post-transfection using a surface immunofluorescence protocol (8), applying ectodomain-directed K36/15 mouse monoclonal antibody prior to detergent permeabilization to detect cell surface Kv1.1. Total cellular Kv1.1 was detected by cytoplasmic directed monoclonal antibody K20/78 following detergent permeabilization. Bound primary antibodies were detected using Alexa-conjugated goat anti-mouse with different isotypes. Cells were viewed under indirect immunofluorescence on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope. Surface versus total staining was scored under narrow-wavelength fluorescein and Texas Red filter sets. One hundred randomly chosen transfected cells per coverslip were scored by eye for relative levels of green fluorescence signal arising from staining of cell surface Kv1.1 versus the level of red fluorescence signal arising from staining of total cellular Kv1.1. Values represent mean ± S.D. of cells judged to be positive for surface staining as determined from three independent coverslips per treatment. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation

Analyses of COS-1 cell lysates prepared from transfected cells were performed as described (8). In brief, transfected COS-1 cells were rinsed and then harvest in ice-cold PBS. Cells were centrifuge 5 min, 1000g, 4°C. The cell pellet was lysed on a tube rotator for 10 min at 4°C in 1 ml of lysis buffer solution containing 10 mM Tris pH 8.00, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA and a protease inhibitor mixture (2 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml antipain, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml benzamidine and 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Crude lysates were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 14,000 × g to pellet nuclei and debris. An equal volume of reducing SDS sample buffer (2×) was added to soluble fractions (8). Samples were boiled and fractioned on SDS/9% polyacrylamide gels. Gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting have been described (8). Blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (ICN), followed by enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Perkin Elmer). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by exposing blots to X-ray film. For immunoprecipitation reactions, 300 μl of detergent lysate was diluted to 1 ml in ice-cold lysis buffer. Monoclonal antibody (2.5 μg) was added and the mixture was incubated a tube rotator at 4°C for 2 h. Antibody-antigen complexes were immobilized by absorption onto 15 μl of settled protein G-Sepharose (Amersham) by incubation on a tube rotator for 1h at 4°C. Protein G beads were washed 5 times in lysis buffer and resuspended in reducing SDS sample buffer and analyzed on 9% (for Kv1.1) or 18% (for DTXk) SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

Enzymatic Digestion

Transfected cell cleared lysates were digested with Neuraminidase (Roche) from Clostridium perfringens (0.25 units/ml in sodium acetate, pH 5.0) overnight at 37°C. Digested products were analyzed by immunoblot. For Proteinase K digestion (Sigma), transfected cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS. Each 35-mm dish was incubated with 10 mM Hepes/150 mM NaCl/2 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4) with or without 200 μg/ml Proteinase K (8) at 37°C for 30 min. Cells then were harvested and centrifuged at 4°C at 1,000 × g in a refrigerated microcentrifuge; Proteinase K digestion was quenched by adding ice-cold PBS containing 6 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 25 mM EDTA. This treatment was followed by three washes in ice-cold PBS. Cleared lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting, as described above.

Electrophysiological Recording

Outward potassium currents were recorded from COS-1 and HEK293 cells transientlyco expressing recombinant wild-type rat Kv1.1 α subunits with empty pSECTAG2 plasmid or with DTXk using whole-cell voltage-clamp technique. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass tubing (TW150F; World Precision Instruments Inc.) to give a resistance of 1-3 mΩ when filled with pipette solution. Currents were recorded with an EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA Electronik), sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz using a digital Bessel filter. All currents were capacitance- and series-resistance compensated, and leak-subtracted by standard P/n procedure. Current recordings were done with continuous superfusion of extracellular buffer, which contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose and 10 HEPES, pH 7.3. Pipette solution contained (in mM) 140 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 glucose and 10 HEPES, pH 7.3. For steady-state activation experiments, cells were held at −100 mV and step depolarized to +80 mV for 200 msec with depolarizing 10 mV increments. For steady-state inactivation experiments, cells were held at −100 mV and step depolarized to +40 mV (test pulse) for 10 sec with 10 mV increments (conditioning steady pulse) followed by a test pulse at +10 mV. The inter-pulse interval was 10 sec. Current density was determined by dividing peak current amplitude at each test potential by cell capacitance, and was plotted against respective test potentials. Conductance-voltage (G-V) and voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation (I-V) relationships were determined as described (36).

PULSE software (HEKA Electronik) was used for acquisition and analysis of currents. IGOR Pro 4 (WaveMetrix, Inc., Lake Oswego, OR), and Origin 7 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA) were used to perform least squares fitting and to create Figures. Data are presented as mean ± SEM or fitted value ± SE of the fit. Paired or unpaired Student's t-tests (Origin) were used to evaluate significance of changes in mean values. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Effects of DTXk coexpression on Kv1.1 surface expression: immunofluorescence staining of intact cells

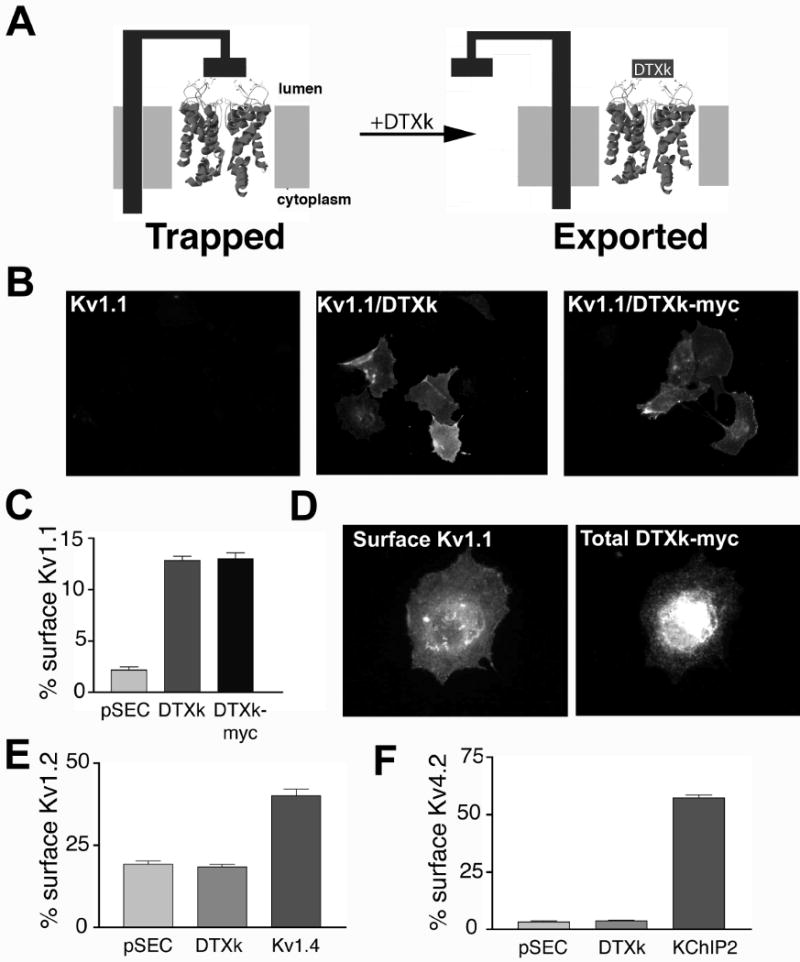

To test whether expression of DTX in the ER lumen of mammalian cells would affect trafficking of Kv1 channels (Fig.1A) we first had to extensively re-engineer the available recombinant DTX expression plasmids, which had been designed for bacterial expression (27). For this, a Dendroaspis polylepis-derived cDNA fragment corresponding to the mature 57 amino acid DTXk polypeptide, generated from the 78 amino acid DTXk propeptide (22), was inserted into the pSecTag2C mammalian expression vector to append a cleavable N-terminal mammalian signal peptide to allow for insertion of DTXk into the ER lumen in mammalian cells. A second plasmid containing a myc epitope-tagged DTXk was also generated in the pSECTag2C vector. COS-1 cells were transiently cotransfected with rat Kv1.1 α subunit cDNA in the presence of either DTXk-myc or DTXk. Control cells were cotransfected with Kv1.1 and either empty pSecTag2C plasmid, or an expression plasmid encoding Kv1.4, whose coexpression enhances surface expression of coassembled Kv1.1 (8). Cells were fixed without permeabilization and stained with an ectodomain-directed anti-Kv1.1 antibody to assay for Kv1.1 surface expression, and then permeabilized and stained with a cytoplasmically-directed anti-Kv1.1 antibody to define cells expressing Kv1.1. Consistent with previous results (8), we found that only a small percentage (2.2 ± 0.3%, n=6) of cells expressing Kv1.1 cotransfected with the empty pSecTag2C plasmid had detectable Kv1.1 surface staining (Fig. 1B, C). Coexpression of Kv1.1 with either DTXk or DTXk-myc in pSecTag2C resulted in the appearance of a new population of cells with robust Kv1.1 surface staining (Fig. 1B, C). The percentage of Kv1.1-expressing cells exhibiting robust surface expression of Kv1.1 upon coexpression with DTXk (12.8 ± 0.9%, n=6) or DTXk-myc (13.0 ± 0.6%, n=6) was significantly (p< 0.005) different than in cells coexpressing Kv1.1 and pSECTag2C (Fig. 1C), but lower than that obtained upon coexpression with Kv1.4 (48.5± 0.6%, n=6). Interestingly, at all concentrations of cDNA tested, a lower percentage of transfected cells (4 μg/dish; 26.7±0.8%, n=4) exhibited DTXk-myc than exhibited Kv1.4 expression (4 μg/dish; 56.7±0.8%, n=4) (p<0.001). The low representation of cells with significant accumulation of intracellular DTXk in the ER lumen might contribute to the limited impact of DTXk versus Kv1.4 coexpression. Cells expressing Kv1.1 and DTXk-myc and exhibiting robust Kv1.1 surface expression also stained with anti-myc antibody (Fig. 1D). However, in these cells DTX-myc was predominantly localized intracellularly (Fig. 1D). To demonstrate that the differences in Kv1.1 surface expression were not unique to COS-1 cells, Kv1.1 and DTXk were coexpressed in a variety of mammalian cells of diverse origin. Similar results were obtained in transfected HEK293 cells (data not shown) and in transfected primary rat astrocytes (see below).

Figure 1.

ER luminal DTXk expression exerts specific effects on Kv1.1 trafficking in COS-1 cells. A, Cartoon depicting competition of soluble DTXk (grey square) in the ER lumen with the putative resident ER protein (black) involved in retention of Kv1 channels. B, COS-1 cells transfected with Kv1.1 and pSECTAG2 (“Kv1.1”), DTXk (1:4 cDNA ratio), or DTXk-myc tag (1:4 cDNA ratio) were stained for surface Kv1.1 in the absence of detergent permeabilization. C, Kv1.1 surface expression efficiency when cotransfected with pSECTAG2, DTXk, DTXk-myc or Kv1.4 (1:4 cDNA ratio). Surface expression was quantified using surface immunofluorescence staining. D, Coexpression of Kv1.1 and DTXk-myc (1:4 cDNA ratio). COS-1 cells were double immunofluorescence stained for surface Kv1.1 and total cellular DTXk. E, COS-1 cells were transfected with DTXk-insensitive Kv1.2 and pSECTAG2, DTXk (1:4 cDNA ratio), or Kv1.4 (1:4 cDNA ratio), and surface expression assayed by surface immunofluorescence staining. F, COS-1 cells were transfected with DTXk-insensitive Kv4.2 and pSECTAG2, DTXk (1:4 cDNA ratio), or KChIP2 (1:1 cDNA ratio). Surface expression was assayed by surface immunofluorescence.

DTXk is a selective blocker of Kv1.1-containing channels, and does not bind to other Kv channels (28). To determine whether DTXk effects on Kv1 channel surface expression were limited to its Kv1.1 target, we assayed effects of DTXk coexpression on ER-localized but DTXk-insensitive Kv1.2 (Fig. 1E) and Kv4.2 (Fig. 1F). In both cases, DTXk did not promote surface expression of homomeric channels formed from these subunits: Kv1.2 with pSECTag2C 19.2± 1.3% vs. 18.4± 0.9% with DTXk (Fig. 1E), and Kv4.2 with pSECTag2C 3.4± 0.6% vs. 3.7± 0.9% with DTXk (Fig. 1F). However, in these same experiments, surface expression of these channels was sensitive to previously described trafficking modulators (8, 24), such as Kv1.4 for Kv1.2 (40.1± 2.3%; Fig. 1E) and the auxiliary subunit KChIP2 for Kv4.2, (57.8± 1.9%; Fig. 1F).

Effects of DTX coexpression on Kv1.1 surface expression as monitored by MAGUK-mediated clustering and N-linked glycosylation

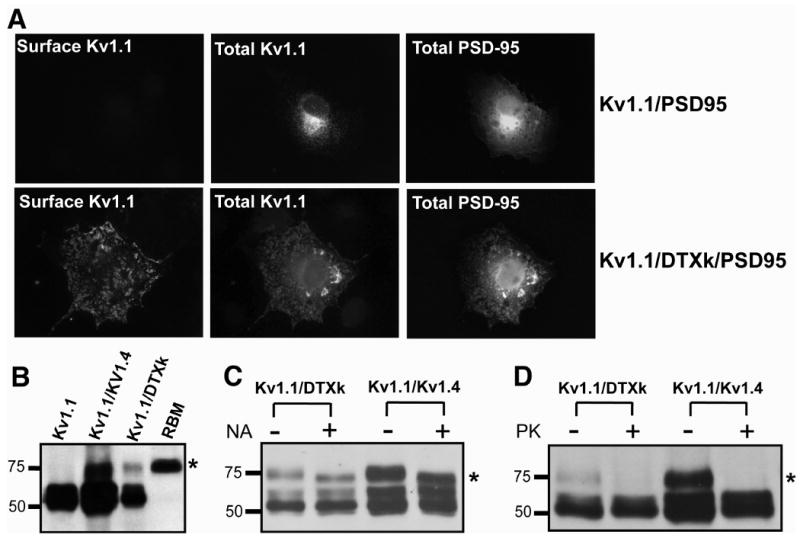

To confirm increased surface expression of Kv1.1 in the presence of DTXk, we assayed the extent of Kv1.1 clustering induced by PSD-95. Previous studies showed that clustering of Kv1 channels by PSD-95 requires their cell surface expression (8, 21). We found that coexpression of Kv1.1, DTXk and PSD-95 leads to robust clustering of cell surface homotetrameric Kv1.1 channels not seen for cells expressing Kv1.1 with pSECTAG2 and PSD-95 (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. DTXk promotes the surface expression of Kv1.1 channels in COS-1 cells.

A, COS-1 cells were transfected with Kv1.1, pSECTAG2 and PSD-95 (1:4:1 cDNA ratio) (upper) or Kv1.1, DTXk, and PSD-95 (1:4:1 cDNA ratio) (lower). Left panel, surface expression was assayed by surface immunofluorescence. Middle and right panels, total cellular Kv1.1 and PSD95 staining. B, COS-1 cells were transfected with Kv1.1 and pSECTAG2 (“Kv1.1”), Kv1.4 or DTXk at 1:4 cDNA ratios as indicated. Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for Kv1.1. * indicates Kv1.1 α subunits with increased Mr due to processing of oligosaccharide chains subsequent to ER export. RBM, rat brain membranes. C, Lysates prepared from COS-1 cells cotransfected with Kv1.1/DTXk or Kv1.1/Kv1.4 at 1:4 cDNA ratio were treated with neuraminidase (sialidase) (+) or buffer alone (-) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for Kv1.1. * indicates sialidase-sensitive population. D, COS-1 cells cotransfected with Kv1.1/DTXk or Kv1.1/Kv1.4 at 1:4 cDNA ratio were treated with Proteinase K (+) or buffer alone (-). Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for Kv1.1. * Proteinase K-sensitive population.

The Kv1.1 α subunit contains a single N-linked glycosylation site located in the extracellular loop between transmembrane segments S1 and S2 (29). Differences in processing of the Kv1.1 N-linked oligosaccharide chain during transit through the secretory pathway can be detected by shifts in relative electrophoretic mobility (Mr) on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and by sensitivity to sialidase digestion (29). Lower Mr forms of Kv1 α subunits carrying simple high mannose chains correspond to ER pools, while higher Mr forms carrying sialylated complex chains correspond to Golgi and plasma membrane pools (8, 14, 29). Cotransfection of DTXk with Kv1.1 at a 1:4 cDNA ratio induced appearance of a new pool of Kv1.1 with a higher Mr (∼75 kDa) corresponding to mature forms of the Kv1.1 N-linked oligosaccharide chain (Fig.2B). Higher Mr forms of Kv1.1 found in DTXk expressing cells were sensitive to treatment with sialidase (Fig. 2C) verifying that they contained Golgi-modified sugar chains.

We next employed an independent biochemical assay of surface expression, using Proteinase K (PK) digestion of intact living cells to cleave extracellular domains of cell surface but not intracellular Kv1.1 (8). The Mr = 75 kD sialidase-sensitive form of Kv1.1 present in DTXk coexpressing cells was sensitive to PK digestion (Fig. 2D), demonstrating cell surface expression. In contrast, the lower Mr (≈ 60 kDa) form of Kv1.1 in cells coexpressing Kv1.1 and pSECTAG2 or DTXk was insensitive to sialidase and PK digestion. These biochemical data are entirely consistent with those from immunofluorescence experiments, and support that DTXk coexpression leads to enhance trafficking of homotetrameric Kv1.1 channels to the cell surface.

Binding of DTXk to Kv1.1 and effects of altering DTX binding affinity on Kv1.1 surface expression

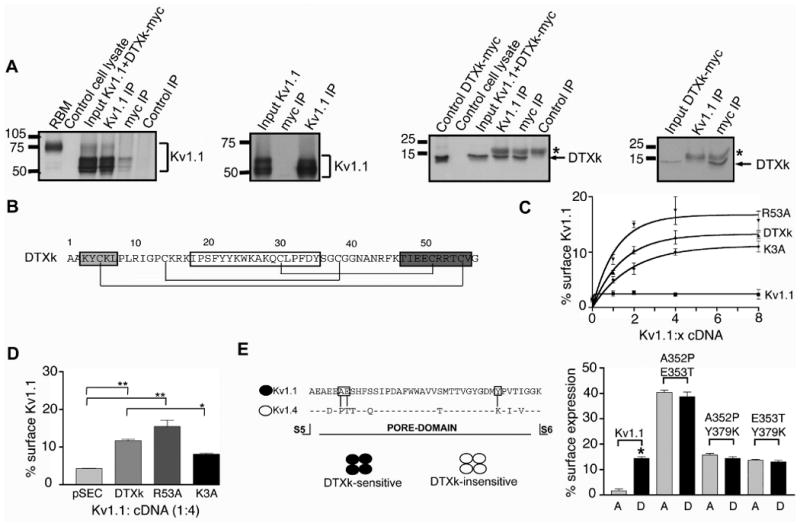

We next tested whether DTXk modulated Kv1.1 trafficking by direct binding. We first performed reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation experiments from cells coexpressing DTXk-myc and Kv1.1. In these experiments, anti-myc antibodies coimmunoprecipitated Kv1.1, and anti-Kv1.1 antibodies coimmunoprecipitated DTXk-myc (Fig. 3A). Neither DTXk-myc nor Kv1.1 were immunoprecipitated with control IgG (Fig 3A). In lysates from singly transfected cells anti-Kv1.1 antibodies did not immunoprecipitate DTXk-myc, and anti-DTXk-myc antibodies did not immunoprecipitate Kv1.1 (Fig. 3A). We found that the overall yield of coimmunoprecipated Kv1.1 obtained using anti-myc antibodies was small compared to the yield obtained using Kv1.1 antibodies, showing that at steady state only a small subset of total Kv1.1 was bound to DTXk. However, most of the DTXk-myc was effectively coimmunopreciptated by anti-Kv1.1, such that when coexpressed, the bulk of cellular DTXk was found associated with Kv1.1. This suggests that the low levels of DTXk-myc staining observed in immunofluorescence experiments (Fig. 1D) may be limiting for Kv1.1 surface expression.

Figure 3. DTXk affect Kv1.1 trafficking properties by directly binding to Kv1.1 channels.

A, Coimmunoprecipitation (IP) experiments performed on COS-1 cell lysates expressing Kv1.1/DTXk-myc (1:4 cDNA ratios) using anti-Kv1.1, anti-myc, and isotype-matched control mouse monoclonal antibodies. “Control cell lysate” corresponds to a cell lysate from untransfected COS-1 cells. Control DTXk-myc was obtained from COS-1 cell lysates singly transfected with DTXk-myc. Middle right and far right panels show specificities of anti-Kv1.1 and anti-myc antibody immunoprecipitations against lysates from COS cells singly transfected with Kv1.1 or DTXk-myc. The bracket and the arrow indicate the position of Kv1.1 and DTXk-myc, respectively. * indicates the mouse IgG light chain band. Input and IP lanes are not normalized. B, Amino acid sequence of DTXk. The secondary structural elements and the cystine bonds are diagrammed with boxes representing: light grey: 310-helix; transparent: β-hairpin; dark grey: α-helix. C, Dose-response curves of surface Kv1.1 in presence of increased amount of pSECTAG (“Kv1.1”), DTXk, or the K3A and R53A point mutants in COS-1 cells, and surface expression quantified by surface immunofluorescence staining. D, Kv1.1 surface expression efficiency when cotransfected with pSECTAG2, DTXk, or the K3A and R53A point mutants (1:4 cDNA ratios) in primary rat astrocytes. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. E, Analysis of Kv1.1 double mutants mutated in the three residues (A352P, E353T and Y379K) critical for DTX binding. Left panel, sequence alignment of P-domain sequences of Kv1.1 and Kv1.4 subunits. The crucial residues for DTX sensitivity are outlined with boxes. Right panel, surface expression of Kv1.1 and double mutants cotransfected in COS-1 cells with pSECTAG2 (A) or DTXk (D) at 1:4 cDNA ratios.

It is known that DTXk interacts with Kv1.1 channels via its 310-helix and β-turn (Fig. 3B; (30). Previous studies revealed that mutation of DTXk lysine (K) 3 to alanine (A) (i.e. K3A) led to ≈ 1000-fold reduction in its inhibitory potency for Kv1.1 (28). In contrast, alanine substitution of basic residues in the α-helix, (e.g. arginine R53), did not significantly alter DTXk binding (30). As an assay of whether altering Kv1.1 binding affinity of DTXk affected its potency of inducing Kv1.1 surface expression, we co-expressed increasing amounts of DTXk-K3A and DTXk-R53A with a fixed amount of Kv1.1 cDNA in COS-1 cells. Systematically increasing amounts of DTXk, K3A or R53A cDNAs resulted in saturable dose-dependent increases in the number of cells with robust Kv1.1 surface staining (Fig. 3B). However, the efficacy of the low-affinity point mutant K3A at inducing surface expression of coexpressed Kv1.1 was significantly lower than wild-type DTXk. Moreover, expression efficiency of the point mutant K3A in COS-1 was similar to wild-type (4 μg/dish; 28.5±1.3% versus 26.7±0.8% respectively, n=4). Co-expression of point mutant R53A resulted in a higher number of cells expressing cell surface Kv1.1 (Fig. 3B). However, only the 1:2 cDNA (Kv1.1:DTXk) ratio showed a significant difference between R53A and wild-type DTXk (p<0.006 versus p<0.14 for 1:4 and 1:8 cDNA ratios).

We next compared effects of coexpressing Kv1.1 with wild-type DTXk, or the K3A or R53A point mutations, in primary rat astrocyte cultures. Cotransfections were done at 1:4 cDNA (Kv1.1:DTXk) ratios, which yielded maximal effect on Kv1.1 cell surface expression in COS-1 cells. As shown in Fig. 4C, K3A again yielded a significantly lower number of cells with Kv1.1 surface staining than did wild-type DTXk (p<0.02). R53A also induced a robust increase in cells expressing surface Kv1.1 compared to cells expressing Kv1.1 and pSECTAG2 but the impact was not significantly different from that obtained with wild-type DTXk. That the effects of these DTXk isoforms on Kv1.1 trafficking parallels their binding affinity suggests that direct binding of exogenous DTXk to Kv1.1 in the ER lumen mediates the observed effects on surface expression of Kv1.1.

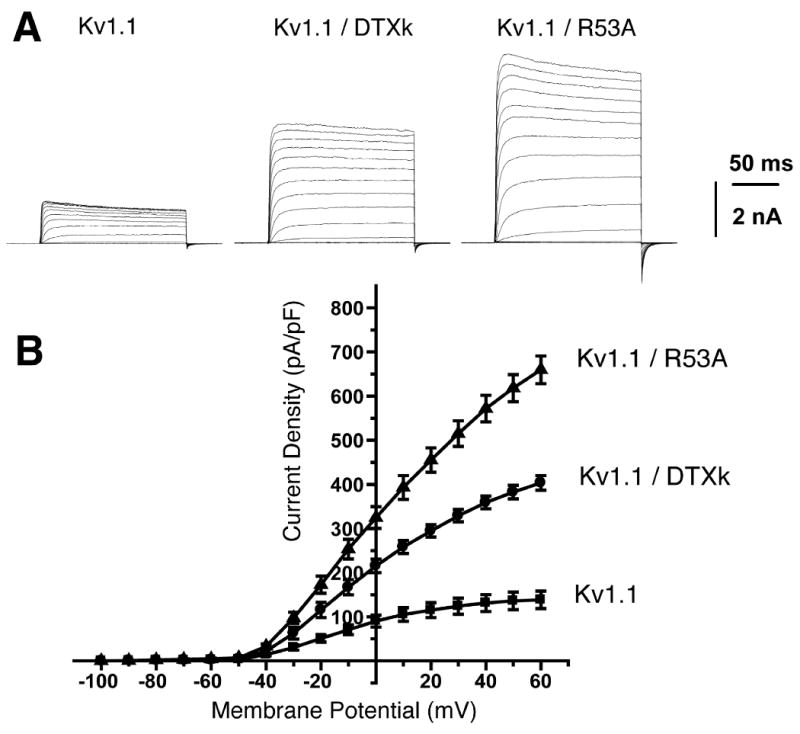

Figure 4. DTXk enhances the surface expression of functional Kv1.1 channels in COS-1 cells.

A, Representative whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of Kv1.1 currents from COS-1 cells transiently expressing Kv1.1 with pSECTAG2 (“Kv1.1”) or with DTXk (ratio 1:4) or DTXk-R53A (ratio 1:2). The cells were held at −100 mV and step depolarized to +60 mV for 200 msec with +10 mV increments. B, Current-voltage relationship of Kv1.1 currents obtained from experiments as in panel A. Peak current amplitudes at each test-potential were divided by the cell capacitance to obtain the current densities. Mean ± SE of current densities obtained (n = 7 each) were plotted against each test potential.

We finally addressed whether the DTXk trafficking effects depended on its binding to the canonical site on Kv1.1 channels by assaying Kv1.1 α subunits mutated in the DTX binding site and that exhibit lowered DTX binding affinities. Previous studies showed that the three critical residues (A352, E353 and Y379) in the Kv1.1 pore region were responsible for high affinity DTX-binding, such that their mutation to corresponding residues present in DTX-insensitive Kv1 channels dramatically reduced DTX binding (17, 19). We mutated these three critical residues to those present in the DTX-insensitive Kv1.4 (A352P, E353T and Y379K; Fig. 3E, left panel). The double point mutants A352P/E353T; A352P/Y379K and E353T/Y379K were coexpressed with DTXk in COS-1 cells at 1:4 cDNA ratios (Fig. 3E, right panel). Although cell surface expression of these mutants was increased compared to wild-type Kv1.1 wild-type when coexpressed with pSECTAG2 (13), none showed a further increase in surface expression when coexpressed with DTXk (Fig.3E). The occlusion of the DTXk trafficking effect by mutation of the DTX binding site strongly suggests that DTXk exerts its effects on Kv1.1 trafficking by binding to the canonical site on Kv1.1 channels.

Patch clamp analysis of Kv1.1 functional expression

We next addressed whether increased expression of cell surface Kv1.1 yielded increased Kv1.1 ionic currents using whole-cell patch-clamp. At a test potential of +40mV, Kv1.1-transfected cells coexpressing DTXk had ≈2.7-fold larger currents (358.9±14.3 pA/pF; n=7) than cells expressing Kv1.1 with pSECTAG2 (131.4± 19.1 pA/pF; p=0.0009; Figure 3A). The increases in Kv1.1 current amplitude occurred in the absence of any changes in voltage-dependent activation, as indicated by similar midpoints of activation conductance-voltage (-12.2 ± 0.7 mV versus -12.9 ± 0.5 mV, n=5) and the steady-state inactivation – voltage (-35.1 ± 0.4 versus - 36.8± 0.7 mV, n=5) relationships for cells expressing Kv1.1 and pSECTAG2 versus Kv1.1 and DTXk. We also assayed the effects of coexpression with the R53A point mutant, which yielded increased Kv1.1 surface expression by cell surface immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 3). Coexpression of R53A led to larger increases in Kv1.1 current amplitude at +40mV (571.6±30.2 pA/pF, n=7; p=0.002) than did DTXk, again in the absence of altered voltage-dependent activation (G1/2 = -13.1 ± 0.6 mV, n=5) or inactivation (Vi1/2 = -36.1 ± 0.8 mV; n=5). Together these data provide compelling evidence that DTXk in the ER lumen binds to the pore region of Kv1.1 homotetramers and facilitates their exit from the ER to allow for cell surface expression of functional Kv1.1 channels.

Discussion

Results presented here establish that luminal ER expression of the mamba snake neurotoxin DTXk increases Kv1.1 intracellular trafficking and cell surface expression. Our previous results (13) suggested that an as yet unknown endogenous ER protein binds to the pore region of Kv1.1 and other DTX-sensitive α subunits (Kv1.2, Kv1.6), and that this binding regulates intracellular trafficking of homo- and hetero-tetrameric Kv1 channels, controlling the subunit composition of surface Kv1 channels. This ER-localized protein is expected to exhibit a domain with a structure analogous to the DTX toxin scaffold, allowing for high-affinity binding to pore region of the Kv1 α subunits (Kv1.1, Kv1.2 and Kv1.6) that exhibit inefficient export from the ER and trafficking to the cell surface. Our results show that expressing soluble DTXk in the ER lumen enhances ER export of Kv1.1 and allows for increased cell surface expression of functional homotetrameric Kv1.1 channels. This is presumably due to a competitive inhibition by luminal DTXk of Kv1.1 binding to the ER retention protein. Prevailing models of DTX binding suggest that the DTX binding affinity for tetrameric Kv1 channels increases with increased number of DTX-sensitive subunits in the tetramer (19, 28). That the experiments presented here support a role for a DTX-like binding event in regulating Kv1 channel surface expression is consistent with our previous findings that surface expression of heteromeric Kv1 channels followed a dose-dependence consistent with the number of DTX-sensitive and –insensitive subunits determining trafficking efficiency (8) and consistent with the observed subunit composition of Kv1 channel combinations observed in vivo (10, 11).

While exogenous ER luminal expression of DTXk promoted Kv1.1 cell surface expression, the effect was not as robust as upon coexpression of Kv1.1 with Kv1.4. Like most vertebrate peptide toxins, DTXk possesses multiple disulfide bonds, whose proper combinatorial formation is required for biological activity. Improper disulfide bond formation, as often occurs upon expression of recombinant toxins in bacterial expression systems, can dramatically lower the toxin's affinity for the channel (19, 31). Our expression of DTXk in COS-1 is the first example of expression of an exogenous non-mammalian neurotoxin in a mammalian cell background. The lack of robust effects of DTXk on Kv1.1 trafficking could be due to the presence of only a small fraction of correctly folded DTXk in the ER lumen. In fact, samples of our DTXk- and DTXmyc-expressing COS-1 cells yielded no detectable DTXk binding activity (Dr. J. Oliver Dolly, personal communication).

The complexity of the ER luminal environment might also influence the interactions of the toxins to the channels. For example, the electrostatic potential and resulting dipole moment of Kv1.2 channels guide and orient the scorpion toxin maurotoxin into its binding site on the Kv1.2 pore-region (32). The local electrostatic fields surrounding ER Kv1.1 channels might affect DTXk guidance and orientation to its pore-region, perturbing binding. Moreover, DTXk is soluble and presumably expressed throughout the three-dimensional volume of the ER lumen, whereas the population relevant for Kv1.1 binding is limited to that adjacent to the luminal face of the ER membrane. Moreover, correctly folded DTXk may flux rapidly out of the ER such that steady-state luminal accumulation of correctly folded DTXk may be quite low. In contrast, coexpressed Kv1.4 is limited to the same two-dimensional space (the ER membrane) occupied by Kv1.1. The high-affinity T1 assembly domain on the N-termini of Kv1 α subunits confers high-affinity and virtually irreversible assembly to the coexpressed subunits. This efficient interaction may contribute to the enhanced efficacy observed for heteromeric Kv1 α subunit assembly relative to DTXk coexpression.

One intriguing result was the enhanced effect of the point mutant R53A on Kv1.1 trafficking. Previous studies (competition binding assay on rat brain membranes and inhibition of Kv1.1 currents in Xenopus oocytes) have shown that the R53A mutation yielded insignificant alterations in the DTXk binding affinity for Kv1.1 (25, 28). The precise mechanism for the DTXk effects on Kv1.1 trafficking are not known, but presumably involve a competition between soluble DTXk and an endogenous ER retention protein for the same binding site on Kv1.1. Whether DTXk binding exerts other effects to enhance Kv1.1 trafficking, such as enhancing channel folding, is not known. Pharmacological rescue of trafficking-defective mutants of HERG K+ channels appears to involve drug-induced restoration of defective folding (30). However, wild-type Kv1.1 does not exhibit obvious misfolding (2) as do these trafficking-defective HERG mutants (30).

It has been suggested that neurotoxins such as DTXk arose from cellular proteins, or prototoxins, operating in normal physiological processes (33). In fact DTXk and other DTX neurotoxins exhibit strong sequence and structural similarity to mammalian Kunitz type protease inhibitors, although the neurotoxins do not inhibit proteases nor do the protease inhibitors bind to ion channels. Previous studies have reported the presence of an endogenous prototoxin, lynx1, in the mammalian nervous system (34). Lynx1 is a neuronal membrane protein adopting a three-fingered toxin fold characteristic of the snake α-bungarotoxin, and as such binds to and inhibits neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (31). We suggest that the putative ER Kv1 binding protein may represent a mammalian prototoxin, in this case regulating the composition of cell surface Kv1 channels through binding and ER retention. This considerable variability in the subunit composition of Kv1 channels in different neurons shapes cell-specific differences in action potential threshold, duration and firing rate. Future studies will be aimed at identifying this protein and understanding how it may contribute to shaping neuronal Kv1 channel abundance and distribution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant NS34383 to J.S.T. We thank Drs. Milena Menegola, Eliana Clark, and Louis. N. Manganas for constructive suggestions, and Dongkai Zhen for technical assistance.

Abbreviations Footnote

- ER

Endoplasmic Reticulum

- DTX

dendrotoxin

- MAGUK

membrane-associated guanylate kinase

- RBM

rat brain membranes

References

- 1.Hille B. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manganas LN, Akhtar S, Antonucci DE, Campomanes CR, Dolly JO, Trimmer JS. Episodic ataxia type-1 mutations in the Kv1.1 potassium channel display distinct folding and intracellular trafficking properties. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:49427–49434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCormack T, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Pountney D, Saganich M, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Rudy B. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. In: Rudy B, Seeburg P, editors. Molecular and functional diversity of ion channels and receptors. Vol. 868. 1999. pp. 233–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ann N Y Acad Sci [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smart SL, Lopantsev V, Zhang CL, Robbins CA, Wang H, Chiu SY, Schwartzkroin PA, Messing A, Tempel BL. Deletion of the K(V)1.1 potassium channel causes epilepsy in mice. Neuron. 1998;20:809–819. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rettig J, Heinemann SH, Wunder F, Lorra C, Parcej DN, Dolly JO, Pongs O. Inactivation properties of voltage-gated K+ channels altered by presence of beta-subunit. Nature. 1994;369:289–294. doi: 10.1038/369289a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhodes KJ, Keilbaugh SA, Barrezueta NX, Lopez KL, Trimmer JS. Association and colocalization of K+ channel alpha- and beta-subunit polypeptides in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5360–5371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05360.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isacoff EY, Jan YN, Jan LY. Evidence for the formation of heteromultimeric potassium channels in Xenopus oocytes. Nature. 1990;345:530–534. doi: 10.1038/345530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manganas LN, Trimmer JS. Subunit composition determines Kv1 potassium channel surface expression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29685–29693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trimmer JS, Rhodes KJ. Localization of voltage-gated ion channels in mammalian brain. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:477–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.113328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch RO, Wanner SG, Koschak A, Hanner M, Schwarzer C, Kaczorowski GJ, Slaughter RS, Garcia ML, Knaus HG. Complex subunit assembly of neuronal voltage-gated K+ channels. Basis for high-affinity toxin interactions and pharmacology. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27577–27581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shamotienko OG, Parcej DN, Dolly JO. Subunit combinations defined for K+ channel Kv1 subtypes in synaptic membranes from bovine brain. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8195–8201. doi: 10.1021/bi970237g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopantsev V, Tempel BL, Schwartzkroin PA. Hyperexcitability of CA3 pyramidal cells in mice lacking the potassium channel subunit Kv1.1. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1506–1512. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.44602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manganas LN, Wang Q, Scannevin RH, Antonucci DE, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. Identification of a trafficking determinant localized to the Kv1 potassium channel pore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14055–14059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241403898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu J, Watanabe I, Gomez B, Thornhill WB. Determinants involved in Kv1 potassium channel folding in the endoplasmic reticulum, glycosylation in the Golgi, and cell surface expression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39419–39427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu J, Watanabe I, Gomez B, Thornhill WB. Heteromeric Kv1 potassium channel expression: Amino acid determinants involved in processing and trafficking to the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25558–25567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu J, Gomez B, Watanabe I, Thornhill WB. Amino acids in the pore region of Kv1 potassium channels dictate cell surface protein levels: a possible trafficking code in the Kv1 subfamily. Biochem J. 2005;388:355–362. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurst RS, Busch AE, Kavanaugh MP, Osborne PB, North RA, Adelman JP. Identification of amino acid residues involved in dendrotoxin block of rat voltage-dependent potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;40:572–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imredy JP, MacKinnon R. Energetic and structural interactions between delta-dendrotoxin and a voltage-gated potassium channel. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:1283–1294. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tytgat J, Debont T, Carmeliet E, Daenens P. The alpha-dendrotoxin footprint on a mammalian potassium channel. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24776–24781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolly JO, Parcej DN. Molecular properties of voltage-gated K+ channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1996;28:231–253. doi: 10.1007/BF02110698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiffany AM, Manganas LN, Kim E, Hsueh YP, Sheng M, Trimmer JS. PSD-95 and SAP97 exhibit distinct mechanisms for regulating K(+) channel surface expression and clustering. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:147–158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campomanes CR, Carroll KI, Manganas LN, Hershberger ME, Gong B, Antonucci DE, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. Kv beta subunit oxidoreductase activity and Kv1 potassium channel trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8298–8305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110276200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bekele-Arcuri Z, Matos MF, Manganas L, Strassle BW, Monaghan MM, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. Generation and characterization of subtype-specific monoclonal antibodies to K+ channel alpha- and beta-subunit polypeptides. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:851–865. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibata R, Misonou H, Campomanes CR, Anderson AE, Schrader LA, Doliveira LC, Carroll KI, Sweatt JD, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. A fundamental role for KChIPs in determining the molecular properties and trafficking of Kv4.2 potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 2003 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306142200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith LA, Reid PF, Wang FC, Parcej DN, Schmidt JJ, Olson MA, Dolly JO. Site-directed mutagenesis of dendrotoxin K reveals amino acids critical for its interaction with neuronal K+ channels. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7690–7696. doi: 10.1021/bi963105g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misonou H, Trimmer JS. A primary culture system for biochemical analyses of neuronal proteins. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;144:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith LA, Lafaye PJ, LaPenotiere HF, Spain T, Dolly JO. Cloning and functional expression of dendrotoxin K from black mamba, a K+ channel blocker. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5692–5697. doi: 10.1021/bi00072a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang FC, Bell N, Reid P, Smith LA, McIntosh P, Robertson B, Dolly JO. Identification of residues in dendrotoxin K responsible for its discrimination between neuronal K+ channels containing Kv1.1 and 1.2 alpha subunits. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:222–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi G, Trimmer JS. Differential asparagine-linked glycosylation of voltage-gated K+ channels in mammalian brain and in transfected cells. J Membr Biol. 1999;168:265–273. doi: 10.1007/s002329900515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang FC, Parcej DN, Dolly JO. alpha subunit compositions of Kv1.1-containing K+ channel subtypes fractionated from rat brain using dendrotoxins. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:230–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harvey AL. Twenty years of dendrotoxins. Toxicon. 2001;39:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu W, Cui M, Briggs JM, Huang X, Xiong B, Zhang Y, Luo X, Shen J, Ji R, Jiang H, Chen K. Brownian dynamics simulations of the recognition of the scorpion toxin maurotoxin with the voltage-gated potassium ion channels. Biophys J. 2002;83:2370–2385. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75251-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohno M, Menez R, Ogawa T, Danse JM, Shimohigashi Y, Fromen C, Ducancel F, Zinn-Justin S, Le Du MH, Boulain JC, Tamiya T, Menez A. Molecular evolution of snake toxins: is the functional diversity of snake toxins associated with a mechanism of accelerated evolution? Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1998;59:307–364. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miwa JM, Ibanez-Tallon I, Crabtree GW, Sanchez R, Sali A, Role LW, Heintz N. lynx1, an endogenous toxin-like modulator of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mammalian CNS. Neuron. 1999;23:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80757-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]