Abstract

Objective

To examine the effectiveness of an individualized problem-solving intervention provided to family caregivers of women living with severe disabilities.

Design

Family caregivers were randomly assigned to an education-only control group or a problem-solving training (PST) intervention group. Participants received monthly contacts for 1 year.

Participants

Family caregivers (64 women, 17 men) and their care recipients (81 women with various disabilities) consented to participate.

Main outcome measures

Caregivers completed the Social Problem-Solving Inventory – Revised, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale, the Satisfaction with Life scale, and a measure of health complaints at baseline and in three additional assessments throughout the year.

Results

Multilevel modeling was used to conduct intent-to-treat analyses of change trajectories for each outcome variable. Caregivers who received PST reported a significant linear decrease in depression over time; no effects were observed for caregiver health or life satisfaction. Caregivers who received PST also displayed an increase in constructive problem-solving styles over the year.

Conclusions

PST may benefit community-residing family caregivers of women with disabilities, and it may be effectively provided in home-based sessions that include face-to-face visits and telephone sessions.

Keywords: Caregivers, Women, Disability, Randomized trial, Problem-solving

Introduction

Family caregivers constitute the “…backbone of our country’s long-term, home-based, and community-based care systems” (Carter, 2008; p. 1). They are the “largest group of care providers” in the United States (Parish, Pomeranz-Essley, & Braddock, 2003, p. 174) and the market value of their unpaid services almost more than doubles that spent on homecare and nursing home services (Arno, 2006; Vitaliano, Young, & Zhang, 2004). The number of family caregivers will continue to increase as our society changes with an aging populace and an escalating rate of chronic, debilitating health conditions (Carter, 2008).

Although family caregivers are expected to competently function as extensions of health care systems (often performing complex medical and therapeutic tasks and ensuring care recipient adherence to therapeutic regimens; Donelan et al., 2002), they operate without adequate training, preparation, or ongoing support from these systems (Shewchuk & Elliott, 2000). The responsibilities of caregiving – and the lack of preparation, guidance and support – often erode the physical and emotional health (Vitaliano, Zhang, & Scanlon, 2003) and the financial resources (Metlife Mature Market Institute, 2006) of many caregivers. The health and well-being of family caregivers is now a stated priority in public health (Talley & Crews, 2007) and mental health policy (Surgeon General’s Workshop on Women’s Mental Health, 2005). Healthy People 2010 (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000) recommends the development of behavioral and social initiatives to promote the well-being of family members who provide assistance in the home to a loved one with a disability.

There are two major concerns with this mandate. First, research concerning interventions for family caregivers of persons with disabilities is lacking. The majority of the research to date has been conducted in caregiving scenarios that are often associated with aging (e.g., dementia, Alzheimer’s disease), and as such, involve conditions that are relatively time-limited. In contrast, many acquired and developmental disabilities may impose a lifetime of caregiver assistance as life expectancies for persons with disability have increased dramatically in recent years (Lollar & Crews, 2003).

Second, research of caregiving scenarios involving disability has been dominated by samples of male care recipients, with little attention to the unique issues encountered by caregivers of women with disabilities who are usually underserved by health care systems. This issue is extremely complex: women comprise two-thirds of the family caregivers in the United States (Donelan, Falik & Des Roches, 2001; Smith, 2007), and on average they are more likely than men to be the only or primary caregiver for a family member (Metlife Mature Market Institute, 2004). Yet women with disabilities are “… most vulnerable to the lack of family caregivers” (Institute of Medicine, 2007; p. 19) because they are more likely than men to be single, divorced, or live with parents and they usually outlive a male partner (Fine & Asch, 1988; Hanna and Rogovsky, 1991). Although the needs of women with disabilities are understudied in psychological research (Nosek & Hughes, 2003), recent studies suggest that the distress and secondary complications they experience (at rates higher than observed among men; Hughes, Robinson-Whelen, Taylor, Petersen, & Nosek, 2005; Nosek, Howland, Rintala, Young, & Chanpong, 2001) may be adversely influenced by physical and social barriers that limit their access and mobility (Nosek & Hughes, 2003). Women with disabilities who report greater affection in the home also report greater self-esteem and less social isolation (Nosek, Hughes, Swedlund, Taylor, & Swank, 2003). The ability of family members to handle caregiver and familial roles appears vital to the well-being of women who are recipients of their care.

One of the first studies of family caregivers of women with disabilities found that mothers were more likely to assume the caregiver role than other family members (Rivera et al., 2006). Furthermore, this study found that caregiver problem-solving abilities accounted for more variance in caregiver depression and well-being than their demographic characteristics and disability severity of the care recipients. These data – consistent with cross-sectional (Dreer, Elliott, Shewchuk, Berry, & Rivera, 2007; Rivera, Elliott, Berry, Oswald, & Grant, 2007) and prospective research (Elliott, Shewchuk, & Richards, 2001; Grant, Elliott, Weaver, Glandon, & Giger, 2006) – imply that problem-solving training programs may be beneficial to these caregivers.

This is critical information because several clinical trials indicate that problem-solving training (PST; D’Zurilla & Nezu, 1999) can effectively lower distress experienced by parents of a child with a brain injury (Wade, Corey, & Wolfe, 2006a; Wade, Corey, & Wolfe, 2006b), by mothers of children with cancer (Sahler et al., 2005), and by family caregivers of stroke survivors (Grant, Elliott, Weaver, Bartolucci, & Giger, 2002) and of persons with spinal cord injuries (Elliott, Brossart, Berry, & Fine, 2008). Unfortunately, the mechanisms through which PST exerts its beneficial effects are presently unclear (Elliott & Hurst, 2008). Early evidence suggested that PST may increase a sense of personal competence, self-regulation and motivation for solving problems, which in turn influenced a decrease in distress (Nezu & Perri, 1989). In the few available studies of PST for caregivers, however, decreases in caregiver distress in response to PST have been associated with increases in problem-solving abilities in some research (Elliott & Berry, 2009; Grant et al., 2002) but not in others (Elliott et al., 2008). Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis concluded that PST – often superior to no-treatment control groups – has yet to be demonstrably superior to bona fide treatment alternatives, such as other counseling strategies or psychosocial programs that may be of benefit to specific groups (Malouff, Thorsteinsson, & Schutte, 2007). There are no “usual programs of care” for community-residing caregivers, but rehabilitation and social service programs occasionally offer educational assistance and materials in the attempt to inform caregivers about community services, self-care, and other topics deemed important to family caregiving. Preliminary work with a relatively small sample (and attrition problems) indicates that PST may be more effective than educational programs in lowering caregiver distress over a 6-month period, but these differences may not be maintained over time (Elliott et al., 2008).

In this paper, we report a clinical trial of PST for family caregivers of women with disability. We tailored PST to meet the unique needs of each participating caregiver using techniques developed in prior work to help caregivers identify and prioritize the particular problems of immediate concern to each individual participant (cf. Elliott & Shewchuk, 2000). This element is essential in developing collaborative partnerships with each caregiver that address “… the needs and preferences of consumers at the heart of every heath care setting” and to facilitate “… the right of these consumers to make care and lifestyle decisions for themselves” (as recommended by the National Commission for Quality Long-Term Care, 2007; p. 1). We used a prospective design that featured multiple measurement occasions over a 12-month period and statistical procedures that permitted an analysis of individual response to PST and to an educational program over time. In this fashion, then, we were able to test the prediction that caregivers who received PST would report less depression over 12 months than caregivers receiving an educational program, and we would be able to examine possible mediators of these effects. Additionally, we also examined the possible beneficial effects of PST on caregiver health complaints and life satisfaction.

Method

Recruitment

Family caregivers of women with disabilities were recruited from newspaper advertisements, public service announcements in local radio stations, home-health agency referrals, and mailings throughout Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Families were also informed of the study during visits at rehabilitation hospitals located in Birmingham, AL, Tupelo, MS, and Warm Springs, GA. Coordinated efforts (including mailings, flyers) were arranged with the United Cerebral Palsy office in Birmingham, AL, with the Alabama Head Injury Foundation, and with a home-health agency in Atlanta, GA. A flyer was also placed on the website for the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Interested individuals contacted the project coordinator via a toll-free telephone number to discuss basic eligibility requirements. The project coordinator traveled to the interested participant’s home to present details about the study, to confirm eligibility, and to obtain signed consent from both the caregiver and care recipient. To be eligible to participate, individuals had to be 18 years or older, have a family member (or “fictive kin”) who was clearly identified as a caregiver (by the caregiver and the care recipient) and living in the same household as the woman with a disability, and the care recipient had a diagnosed disability. Participants had to have a telephone at home to be in the project, and the caregiver had to agree to random assignment to one of two groups (PST, education-only control group).

Prospective participants were informed they would be randomly assigned to either a problem-solving training program or a telephone follow-up program. The problem-solving training group would entail four home visits and monthly telephone sessions (in the alternate months) with a staff member who would teach them problem-solving skills. The control group was described as an education-only experience, and the problem-solving training would be offered to participants assigned to the control group upon completion. Participants understood their involvement would require a 12-month commitment and questionnaires would be administered to them on four different occasions.

Participants were also informed they would receive a financial stipend for their involvement. Three different funding agencies supported the research project. The budget from one source provided $75.00 to a consenting caregiver and care recipient for participating. The other two sources provided $25.00 to a consenting caregiver and to the care recipient for participating. Prospective participants were not aware of the different stipend amounts at any time.

Fig. 1 contains the number of caregivers who expressed some interest in the study and who were assessed for eligibility. Of the 199 caregivers who expressed interest in the study, 61 did not meet inclusion criteria and 30 declined to participate once informed of the study. Seventeen caregivers did not respond to letters or telephone calls from the project coordinator (after expressing initial interest and requesting information), two were disqualified after displaying inappropriate (e.g., hostile, rude, bizarre) behaviors upon screening, and seven caregivers were dropped from participation when they were not at their residence for the first home visit with the project coordinator. Another caregiver was not able to participate when the home telephone was disconnected. Internal review board guidelines and privacy assurances prevented any systematic collection of personal information from interested individuals who were ineligible or who declined to participate.

Fig. 1.

The CONSORT flowchart.

Treatment conditions

Problem-solving training

In the PST group, a trained interventionist made monthly contact with an assigned caregiver and in-home PST sessions were conducted at months 1, 4, 8 and 12. Telephone sessions were conducted once a month on the alternate 8 months.

The PST protocol was adapted from previous intervention studies (e.g., Grant et al., 2002; Nezu, Felgoise, McClure, & Houts, 2003). In the initial face-to-face session in the home, the five basic principles of the social problem-solving model were presented (identify the problem, brainstorm solutions, critique the solutions, choose and implement a solution and evaluate the outcome; D’Zurilla & Nezu, 1999). The interventionist used a card-sort task that presented problems obtained in focus groups conducted with caregivers of women with various disabilities to help each caregiver identify and prioritize problems unique to their situation (Elliott & Shewchuk, 2000). The interventionist helped the caregiver discuss feelings associated with the problem and generate a list of possible solutions and goals to address the problem and negative feelings associated with it. The PST protocol was designed to promote elements of constructive problem-solving (including identifying and prioritizing problems, regulating emotional experiences, attending to negative and positive cognitions, brainstorming and evaluating solutions, using instrumental, rational problem-solving skills; D’Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 2004).

The interventionist recorded reactions for each step and notes about the interaction directly on the script for use in future sessions. These notes were reviewed by the project coordinator to ensure that the interventionist was providing training in problem-solving techniques and principles in each face-to-face session.

Telephone sessions were based on scripts used in a previous protocol (Grant et al., 2002). A worksheet provided guidelines and prompts for each session. After the initial greeting, the interventionist discussed the value of a positive orientation for solving problems (including positive, optimistic attitudes and positive emotions) and for being (including acknowledging the role of caregiving as a challenge), and reviewed any progress on the problems, goals and planned activities identified in the previous session. This required a review of the problem-solving plan and an evaluation of its relative success. The interventionist assisted the caregiver in identifying current problems and feelings associated with them. The caregiver explored possible solutions and goals with the interventionist, and developed plans, goals and activities to address the problem and negative feelings associated with it. The interventionist completed each section of the script with notes about the interaction with the caregiver, and provided details about the specific elements of PST that were addressed in the session.

Education-only control group

Caregivers assigned to the education-only control group received monthly telephone calls from a control group specialist. During these structured telephone conversations of 10–15 min in length, previously mailed health-education materials were reviewed. Topics included family disaster planning, emotions, humor, relaxation, health and wellness, dental health, osteoporosis, exercise, respite, pain, stress, and long-term care. The control group experience was designed to: (a) engage participants sufficiently to stay involved over a 12-month period; (b) to provide information of particular interest and benefit to caregivers; and (c) to provide a bona fide treatment alternative to PST.

Interventionist, control group specialists and assessors

The interventionist was a Caucasian man with a doctoral degree in administration with no prior experience counseling others. The interventionist was trained by the project coordinator (a Latino-American woman with a PhD. in clinical psychology) in the problem-solving model and in the PST protocol. Part of the training required the interventionist to be supervised by the project coordinator on two home visits (total training approximately 30 h). The project coordinator reviewed all notes from each subsequent face-to-face home visit.

Two Caucasian men served as control group specialists at different times during the project. Neither had prior experience as a counselor; neither was familiar with the principles of PST. Both were trained by the project coordinator in the specific topics to be covered and in the use of the educational manual and control group protocol. Inspection of their session notes revealed that neither discussed any aspect of the social problem-solving model with participants.

Two individuals were trained to conduct assessments with participants at baseline, and at 4, 8, and 12 months of participation. The first assessor – who conducted assessments in the first 4 years of the 5-year project – was a Caucasian woman who had a bachelor’s degree in psychology. The second assessor – who conducted assessments in the final year of the project – was a Caucasian woman with a PhD. in developmental psychology.

The assessors were not informed by staff of group assignments and information from the assessment batteries was not shared with the interventionist or with the control group specialists. The project coordinator supervised the interventionist, the control group specialists, and the assessors separately.

Fidelity of the PST condition

As a check on treatment fidelity in the PST intervention, we reviewed the interventionist’s case notes for all telephone contacts with caregivers. Two reviewers read case notes for each session in the PST group and rated the presence or absence of the following six treatment components: (1) reviewed caregiver problems, goals, and planned activities from previous contact; (2) identified and defined current problems; (3) discussed caregiver feelings about problems; (4) discussed goals and outcomes; (5) identified possible solutions for each problem; and (6) selected and testing solutions. For each session, the number of components (from 0 to 6) was recorded.

Assessments

Following the initial contact the project coordinator scheduled a second appointment for an assessor to visit the consenting caregiver to administer the baseline measures. All assessments were conducted in regularly scheduled intervals with an assessor. The assessor was responsible for entering the data upon returning to the project site, and for scheduling subsequent visits with each participant for the 6, 9, and 12-month assessments.

Debriefing

Participants were debriefed at the final assessment. Participants who completed the education-only control group were offered the opportunity to receive PST. Participants were told the study investigated the benefits of a problem-solving training program and of an educational program for caregivers and their experience in the assigned group was discussed.

Primary outcome variable

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD; Radloff, 1977) was used to assess caregiver depression. The CESD contains 20 items that assess various symptoms associated with depression. Items are scored on a four-point scale to indicate how often symptoms are experienced in the preceding week. Scores range from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depressive behavior. Alpha coefficients have ranged from 0.84 to 0.90 (Radloff, 1977).

Secondary outcome variables

Life satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) was used to evaluate subjective life satisfaction of caregivers and care recipients. The SWLS is a five-item instrument with items rated on a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater life satisfaction. Psychometric studies of the SWLS have evidenced internal consistency (α = 0.87) and reliability (2-month test-retest coefficient = 0.82; Diener et al., 1985).

Caregiver health complaints

The general form of the Pennebaker Inventory of Limbic Languidness Scale (PILL; Pennebaker, 1982) was used to assess caregiver health complaints. The PILL contains 54 items that are rated in a yes–no format and measures health problems experienced by the individual over the preceding 3 weeks. Higher scores reflect more health complaints. The PILL general form has adequate internal consistency (0.88) and test–retest reliabilities over a 2-month period have ranged from 0.79 to 0.83 (Pennebaker, 1982). PILL scores have been correlated with physician visits, aspirin use within the past month, days of restricted activities due to illness, drug and caffeine use, sleep and eating patterns, and with scores on related measures (Pennebaker, 1982).

Social problem solving abilities

The Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R; D’Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 2002) was used to assess caregiver social problem-solving abilities. The SPSI-R has 52 items that are rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from not very true of me (0) to extremely true of me (4). Higher scores on each scale indicate a greater propensity in that facet of problem-solving. The SPSI-R has five scales. Two scales measure the constructive dimensions of the problem-solving model: positive problem orientation (PO) and rational problem-solving (RPS); the negative problem orientation (NO), impulsivity/carelessness style (IC), and avoidance style (AV) assess aspects of a dysfunctional problem-solving style (D’Zurilla et al., 2004).

Following current theoretical recommendations (D’Zurilla et al., 2004), we examined separate constructs of constructive and dysfunctional problem-solving styles. The two positive measures (PO, RPS) were summed to obtain an index of a constructive problem-solving style and the three negative measures (NO, AV, IMP) were summed to form an index of a dysfunctional problem-solving style. Confirmatory, exploratory, and principal component factor analyses with different samples have supported this conceptualization (Berry, Elliott, & Rivera, 2007; Johnson, Elliott, Neilands, Morin, & Chesney, 2006; Rivera et al., 2007).

Functional deficits

The severity of disability of each care recipient was measured with the Functional Independence Measure (FIMSM; Uniform Data Set for Medical Rehabilitation, 1996). The FIMSM contains 13 items that assess motor function (eating, grooming, bathing, dressing, toileting, bowel and bladder control, transfers, and locomotion) and five items that measure cognitive function (communication and social cognition). Each item on the scale ranges from 1 (total assistance) to 7 (complete independence). Lower scores indicate more functional deficits. The FIMSM has evidenced adequate validity and reliability (Chau, Daler, & Andre, 1994; Dodds, Martin, Stolov, & Deyo, 1993; Granger, Cotter, Hamilton & Fiedler, 1993).

Randomization

The first author used a simple randomization strategy (with a random numbers table) to assign participants to the PST group or to the education-only control group. The first author had no information about the caregiver or care recipient at the time of randomization. As depicted in Fig. 1, 38 caregivers were randomly allocated to the PST group and 43 were assigned to the control group.

Statistical analyses

We first examined the comparability of the PST and control groups on demographic, initial status, and care recipient variables to determine the effectiveness of our randomization procedures in providing roughly equivalent initial groups. To test for baseline differences, we used independent-samples t-tests to compare groups on continuous variables, and χ2 tests of independence for categorical variables. We also examined correlations among baseline variables as a check on the construct validity of outcome measures.

To test the effects of the PST intervention on caregiver depression and the secondary outcome variables (health complaints, satisfaction with life, and problem-solving abilities), we used individual linear growth curve modeling for predicting each outcome from treatment condition, time, and the interaction of treatment with time (two-tailed tests; p < 0.05). Linear growth curve modeling is an excellent tool for analyzing trajectories of change over time in designs that feature repeated outcome measures; it can be used to study group differences in trajectories and to detect possible mediators of intervention effects in these designs (Laurenceau, Hayes, & Feldman, 2007). As opposed to traditional analyses of variance, growth curve models can yield accurate and reliable results despite the presence of missing data caused by attrition or loss to follow-up (Kwok et al., 2008), and they can provide more precise results compared to more commonly used regression approaches (Hox, 2002; Snijders & Bosker; 1999).

For our purposes, a significant interaction of treatment with time was interpreted as evidence for a differential treatment effect. Models were estimated with restricted maximum likelihood methods (REML) implemented with the linear mixed models (LMM) routine of SPSS (version 15). Multilevel analyses are recommended approaches for RCTs in which unmeasured and uncontrollable factors - frequent in community-based trials - can potentially affect attrition, treatment adherence or outcomes at any time (West et al., 2008).

In our models, time was treated as a continuous variable (coded 0–3) so that intercepts reflect baseline status. The analyses made use of all available data rather than listwise deletion of cases; consequently, data from all participants were used in each model regardless of missing data or completion status. This feature of LMM provides a simultaneous and sophisticated procedure for conducting conservative intent-to-treat analyses with all available data (Kwok et al., 2008).

For all models, individual slopes and intercepts were treated as random effects and a general unstructured variance–covariance matrix was estimated. We examined the missing value patterns for depression and the four secondary outcome variables (health complaints, life satisfaction, and the two problem-solving variables) over all testing occasions. The subject × time × outcomes matrix was 85.5% complete for the whole sample (83.6% for the PST group, 87.2% for the control group).

Results

Sample

Consenting participants included 17 men and 64 women in caregiver roles for a woman with a disability. The sample was comprised of 55 Caucasian and 26 African–American individuals. Caregivers averaged 57.72 years of age (SD = 11.88, range 31–83) and 13.62 years of formal education (SD = 2.91; range 7–22 years). Forty-four caregivers were married, 19 were divorced, 11 were widowed, three were separated and four reported their marital status as single. The sample averaged 194.81 months in a caregiver role for the family member (SD = 182.35, median = 132, range 3–708 months).

The majority of caregivers were mothers (N = 44) and husbands (N = 14) of the care recipient. Other caregivers were daughters (N = 2), fathers (N = 2), sisters (N = 2), aunts (N = 2), one grandparent, and 12 individuals who described their relationship as “other.” To ensure consenting caregivers could understand the verbal instructions and written materials, we administered the Folstein mental status examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975); consenting caregivers averaged 28.56 on the Folstein mental status examination (SD = 1.80; range 20–30).

Care recipients also had to consent to the project, although they did not participate in the PST or control group experiences. Women who consented to participate with their caregivers had a variety of disabilities, including traumatic brain injury (N = 17), cerebral palsy (N = 16), stroke (N = 12), mental retardation (N = 9), dementia (N = 3), Alzheimer’s disease (N = 3), and 21 care recipients had other severe disabilities (e.g., polio, Angelman’s syndrome, Down’s syndrome, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, fetal hydantoin, spinal meningitis, tuberous sclerosis, Prader–Willi syndrome, muscular dystrophy, Rett’s syndrome, arthritis). Care recipients averaged 44.70 years of age (SD = 21.72, range 19–90 years).

Demographics and baseline status

Table 1 provides demographic and baseline status data for caregivers and care recipients in the treatment and control groups. The only significant group difference was for caregiver baseline constructive problem-solving scores: caregivers in the PST group had significantly lower constructive scores than those assigned to the education-only control group. The difference between groups on dysfunctional problem-solving approached significance (p = 0.09), indicating a trend toward higher dysfunctional problem-solving among caregivers in the intervention group. Because the number of months as a caregiver was highly positively skewed, we also calculated a Mann–Whitney U-test to compare groups on this variable. There was no significant difference between the PST (mean rank = 41.6) and education-only control groups (mean rank = 40.5), U = 793.5, p = 0.82.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline status.

| Categorical variables | Control (N = 43) |

Treatment (N = 38) |

Test (p value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Caregivers | |||||

| Male | 11 | 25.6 | 6 | 15.8 | 0.28 |

| African–American | 14 | 32.6 | 12 | 31.6 | 0.93 |

| Married | 25 | 58.1 | 19 | 50.0 | 0.74 |

| Unemployed | 27 | 62.8 | 21 | 55.3 | 0.79 |

| Receiving help | 11 | 25.6 | 8 | 21.1 | 0.63 |

| Care recipients | |||||

| African–American | 13 | 30.2 | 12 | 31.6 | 0.90 |

| Married | 9 | 20.9 | 9 | 23.7 | 0.91 |

| Unemployed | 41 | 95.3 | 35 | 92.1 | 0.34 |

| Continuous Variables | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Caregivers | |||||

| Age | 58.4 | 13.6 | 56.9 | 9.6 | 0.57 |

| Years education | 13.9 | 2.7 | 13.3 | 3.2 | 0.43 |

| Months caregiving | 190.4 | 184.2 | 199.7 | 182.5 | 0.82 |

| Caregiver MMSE | 28.4 | 1.7 | 28.7 | 1.9 | 0.28 |

| Depression | 11.5 | 11.0 | 15.7 | 12.4 | 0.11 |

| Physical symptoms | 11.4 | 9.3 | 11.5 | 8.4 | 0.98 |

| Satisfaction with life | 23.6 | 8.4 | 21.2 | 8.8 | 0.21 |

| Constructive problem-solving | 66.4 | 18.7 | 58.5 | 12.9 | 0.04 |

| Dysfunctional problem-solving | 22.1 | 20.3 | 29.8 | 18.9 | 0.09 |

| Care recipients | |||||

| Age | 48.1 | 23.1 | 40.9 | 19.7 | 0.14 |

| Years education | 12.2 | 3.6 | 11.6 | 4.3 | 0.55 |

| MMSE | 19.2 | 10.3 | 15.6 | 10.8 | 0.19 |

| FIM | 91.1 | 39.6 | 93.0 | 40.8 | 0.84 |

The FIM was also administered at the final assessment. For the PST group, the final FIM mean was 93.1 (SD = 40.8); for the education-only group, 91.1 (SD = 39.6). A repeated measures ANOVA indicated no significant main effect for time on FIM scores, F(1,66) = 2.43, p = 0.13, and no significant interaction between treatment group and time, F(l,66) = 1.42, p = 0.24.

Table 2 presents correlations among outcome variables at baseline for the PST and control groups combined. As expected, depression was positively associated with number of physical symptoms and negatively associated with life satisfaction. As in previous studies, dysfunctional problem-solving was significantly associated with the outcomes measures in theoretically-consistent directions. We also calculated Spearman rank-order correlations between the months spent in the caregiver role with all outcomes at each assessment. There was no significant association between months in the caregiver role and any outcome on any occasion. The correlations ranged from −0.21 to 0.15.

Table 2.

Correlations among outcome variables at baseline.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Depression | - | |||

| (2) Physical symptoms | 0.60*** | - | ||

| (3) Life satisfaction | −0.61*** | −0.39*** | - | |

| Problem-solving | ||||

| (4) Dysfunctional | 0.63*** | 0.29** | −0.39*** | - |

| (5) Constructive | −0.30** | 0.03 | 0.21 | −0.45*** |

Treatment fidelity

Two raters working independently coded scripts for each telephone session in the PST condition for the number of elements of the problem-solving training program discussed in the session (ranging from 0 to 6). There was exact agreement between raters on 274 of 279 sessions (98.2%). To assess inter-rater agreement, we used intra-class correlations based on a two-factor analysis of variance (with both raters and sessions as random effects) to determine reliability of absolute level of agreement. The estimated reliability for a single rater was 0.98; the estimated reliability for an average of two raters was 0.99. For cases of disagreement, the average of the two raters was used as the measure of treatment compliance. The average number of components per session, taken across all sessions, was 4.6 (SD = 0.64), with a median of 4.9 and a range from 3.3 to 5.5.

Treatment effects

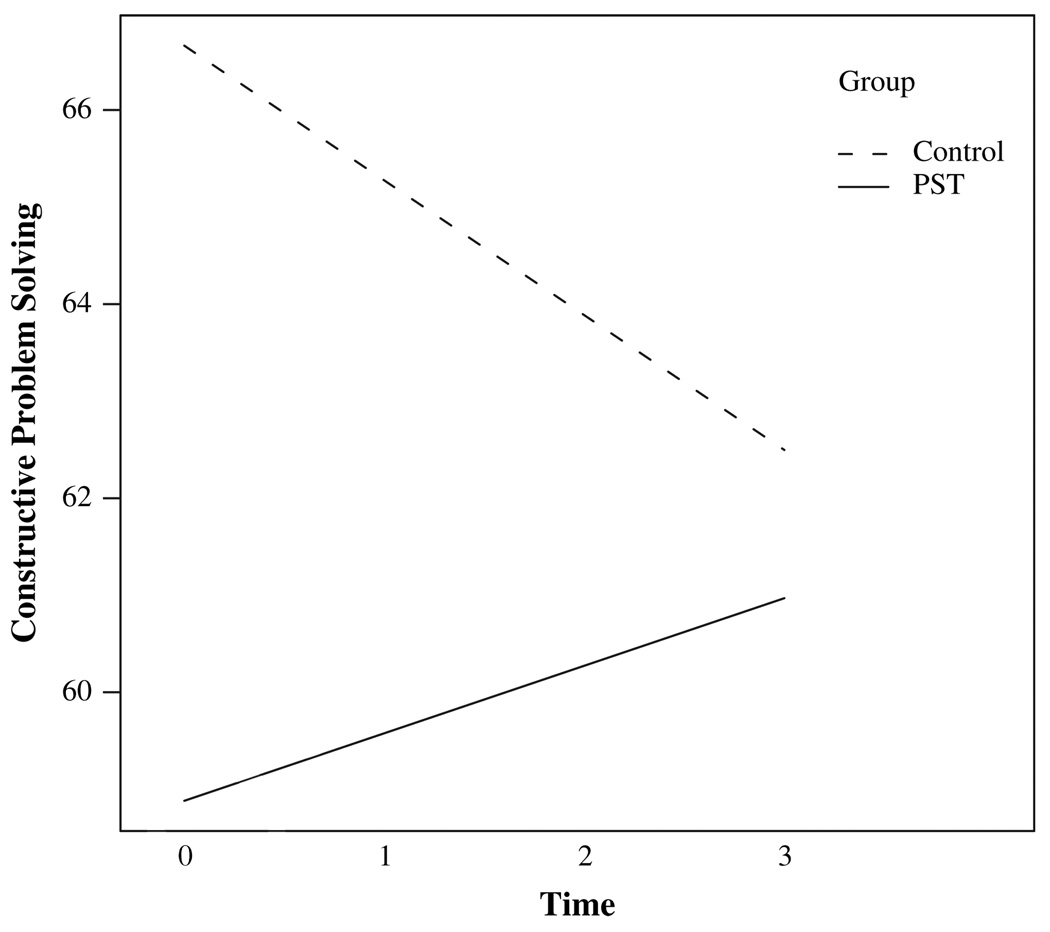

Table 3 displays descriptive statistics for all outcome variables at each assessment period. In Table 4 we provide parameter estimates for the growth curve models used to assess treatment effects. The fixed-effects models indicate significant interactions between treatment and time (i.e., differential time trajectories) for depression (β = −0.10) and for constructive problem-solving (β = 0.07) (βS = standardized regression coefficients). As an effect size, we used the standardized mean gain score estimate of Lipsey and Wilson (2001), which provides an estimate of relative change from initial to final status (in Cohen’s d metric) between the PST and the education-only control groups. For depression, d = −0.57, which indicates a moderate decline in depression for the PST group relative to the education-only control group. For constructive problem-solving, d = 0.27, which indicates a small relative gain in constructive problem-solving for the PST group. Fig. 1 displays the modeled trajectories for the PST and education-only groups on depression (the primary outcome variable), indicating that the PST group experienced a linear decline in depression and caregivers in the education-only group experienced an increase in depression. Fig. 2 compares modeled trajectories for both groups on constructive problem-solving, illustrating a linear increase in constructive problem-solving for the PST group and a decline in the control group.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for outcome variables at each assessment period.

| Control | PST | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | |

| Depression | ||||||

| Tl | 43 | 11.5 | 11.0 | 38 | 15.7 | 12.4 |

| T2 | 39 | 14.1 | 11.9 | 30 | 15.2 | 12.3 |

| T3 | 32 | 13.1 | 10.0 | 30 | 16.3 | 11.9 |

| T4 | 38 | 16.1 | 12.9 | 33 | 13.9 | 11.3 |

| Physical symptoms | ||||||

| Tl | 43 | 11.4 | 9.3 | 38 | 11.5 | 8.4 |

| T2 | 39 | 10.4 | 8.9 | 30 | 10.4 | 7.5 |

| T3 | 32 | 10.9 | 8.2 | 30 | 13.3 | 7.6 |

| T4 | 38 | 11.2 | 7.8 | 34 | 11.5 | 7.8 |

| Satisfaction with life | ||||||

| Tl | 43 | 23.6 | 8.4 | 38 | 21.2 | 8.8 |

| T2 | 39 | 22.4 | 7.8 | 30 | 21.9 | 8.9 |

| T3 | 32 | 24.1 | 7.1 | 30 | 19.7 | 9.3 |

| T4 | 38 | 24.6 | 7.4 | 34 | 20.9 | 9.4 |

| Constructive problem-solving | ||||||

| Tl | 43 | 66.4 | 18.7 | 37 | 58.5 | 12.9 |

| T2 | 39 | 66.5 | 17.3 | 30 | 58.9 | 13.5 |

| T3 | 32 | 66.2 | 17.2 | 30 | 60.0 | 13.4 |

| T4 | 37 | 62.6 | 18.4 | 33 | 60.5 | 15.1 |

| Dysfunctional problem-solving | ||||||

| Tl | 43 | 22.1 | 20.3 | 38 | 29.8 | 18.9 |

| T2 | 39 | 24.8 | 18.8 | 30 | 31.4 | 18.4 |

| T3 | 32 | 20.8 | 17.4 | 30 | 31.4 | 20.7 |

| T4 | 38 | 23.0 | 18.7 | 34 | 28.2 | 19.6 |

Table 4.

Parameter estimates for growth curve models.

| Random effects | Fixed-effects estimates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | Group | Time | Group × time | |||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | ||||

| Outcomes | |||||||||

| Depression | 4.24 | 2.57 | 1.39* | 0.61 | −1.81* | 0.88 | |||

| τ00 | 97.64** | 21.61 | |||||||

| τ11 | 4.80* | 2.71 | |||||||

| τ01 | −8.53 | 6.03 | |||||||

| Physical symptoms | 0.22 | 1.92 | −0.09 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.47 | |||

| τ00 | 61.55** | 11.91 | |||||||

| τ11 | 0.65 | 0.81 | |||||||

| τ01 | −4.55 | 2.37 | |||||||

| Satisfaction with life | −1.80 | 1.82 | 0.35 | 0.37 | −0.64 | 0.53 | |||

| τ00 | 52.58** | 10.72 | |||||||

| τ11 | 1.40 | 1.46 | |||||||

| τ01 | −2.39 | 2.46 | |||||||

| Problem-solving | |||||||||

| Constructive | −7.78* | 3.37 | −1.38 | 0.71 | 2.10* | 1.03 | |||

| τ00 | 168.75** | 37.06 | |||||||

| τ11 | 2.92 | 3.98 | |||||||

| τ01 | 3.99 | 8.73 | |||||||

| Dysfunctional | 7.64 | 4.36 | −0.06 | 0.71 | −0.52 | 1.03 | |||

| τ00 | 338.51** | 61.57 | |||||||

| τ11 | 7.54* | 3.63 | |||||||

| τ01 | −16.48 | 11.07 | |||||||

τ00, variance of intercepts; τ11, variance of slopes; τ01, covariance of intercepts and slopes.

Fig. 2.

Significant treatment × time interaction on caregiver depression.

The random components of the models (Table 4) indicate significant individual differences in intercepts (baseline status) on all outcome variables. There was significant variation in slopes only for depression and dysfunctional problem-solving. The tests of co-variation between intercepts and slopes suggest that there was no significant association between initial status and pattern of change on any of the outcome variables.

Because treatment groups differed in baseline constructive problem-solving (and approached significance for dysfunctional problem-solving), we examined whether the differential treatment effect on depression might be influenced by initial problem-solving skills. Therefore, we conducted growth curve analyses for depression as before but included baseline problem-solving as time-invariant covariates in the model. Baseline constructive problem-solving was not significantly associated with depression across time, B = −0.09, SE = 0.07, β = −0.11, t(77.1) = −1.28, p = 0.21, and the interaction of treatment with time on depression remained statistically significant, B = −1.80, SE = 0.89, β = −0.10, t(73.4) = −1.99, p < 0.05. Baseline dysfunctional problem-solving was significantly associated with depression over time, B = 0.29, SE = 0.05, β = 0.48, t(80.1) = 6.26, p < 0.01. However, the interaction of treatment with time on depressive symptoms remained significant, B = −1.85, SE = 0.89, β = −0.09, t(74.0) = −2.08, p < 0.05.

Because of the significant main effect for treatment and the interaction of treatment with time on constructive problem-solving, we hypothesized that constructive problem-solving would mediate the observed treatment effect on depressive symptomatology (i.e., mediated moderation). To assess for mediated moderation, we followed procedures recommended by Muller, Judd, and Yzerbyt (2005) extended to longitudinal data (Shrout, 2006) for decomposing possible mediation effects. We therefore conducted a growth curve analysis predicting depression scores as above, but we included constructive problem-solving scores as a time-varying covariate and also included the interaction of problem-solving with time in the model. The interaction of treatment with time on depression dropped in magnitude (from B = −1.81 to −1.29) and was no longer statistically significant, β = −0.05, t(70.8) = −1.48, p = 0.14. Furthermore, the interaction of constructive problem-solving with time on depression scores was statistically significant, B = 0.09 (SE = 0.03), β = 0.14, t(97.7) = 3.26, p < 0.01. Combined with the significant main effect for PST in predicting constructive problem-solving (see Table 4), these results meet the criteria for inferring mediated moderation and suggest that the impact of PST on depression over time was due - at least, in part - to the effects of PST on constructive problem-solving.

Post-hoc analyses

Age as a mediating factor

The two treatment groups did not differ significantly in caregiver age (see Table 1), but age was correlated with depression at baseline for the total sample, r(79) = −0.32, p < 0.01. We were interested in determining any possible influence of caregiver age on the effects of PST on caregiver depression. We computed a growth curve model for depression that included age as a covariate. The effect for age was significant, B = −0.25, SE = 0.09, β = −0.27, t(80.5) = −2.79, p < 0.01. However, the interaction of treatment with time on depression remained significant after controlling for age, B = −1.84, SE = 0.88, β = −0.09, t(74.6) = −2.08, p < 0.05. Thus, the effectiveness of PST in lowering caregiver depression was unrelated to caregiver age.Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Significant time × treatment interaction on caregiver constructive problem-solving style.

Care recipient functional impairment

We were also concerned that the functional impairment of the care recipient may have influenced treatment outcomes. The measure of care recipient functional impairment (FIM) was not significantly correlated with depression at baseline, r(78) = 0.01, p = 0.90, nor at the final assessment, r(67) = −0.20, p = 0.10. Nevertheless, to ensure that change in functional deficits were unrelated to treatment effects, we computed a growth curve model for depression using the FIM (taken at baseline and final assessment) as a time-varying covariate. The FIM was not significantly associated with depression (B = −0.02, SE = 0.03, β = −0.08, t(86.8) = −0.84, p = 0.40) and the interaction of treatment with time on depression remained significant (B = −2.06, SE = 0.89, β = −0.10, t(72.0) = −2.30, p < 0.05. Consequently, the effect of PST on caregiver depression was unaffected by the functional deficits of the care recipient.

Skewed distribution of outcome variables

Three outcome variables were moderately skewed: caregiver depression, health complaints, and dysfunctional problem-solving. We log transformed these variables and computed the predictive model with these transformed variables. There were no changes in the results. For example, in the analyses concerning caregiver depression – the most important variable that was skewed – the interaction was remained significant (B = −0.08, SE = 0.03, t(69.2) = −2.38, p = 0.02).

Possible effects of fidelity to PST protocol

In a series of exploratory analyses, we replicated our previous growth curve models, but used the average number of treatment components as a continuous predictor of caregiver outcomes. In these analyses, control group caregivers were coded as 0 treatment components, and PST caregivers were coded according to their average number of treatment components across sessions (i.e., codes ranging from 3.3 to 5.5). The results essentially replicated the previous growth curve findings. There was a significant interaction between number of treatment components and time in predicting depression (B = −0.37, SE = 0.18, p < 0.05) and constructive problem-solving (B = 0.46, SE = 0.22, p < 0.05). Interestingly, the main effect of number of treatment components was positively associated with depression across time (B = 1.08; SE = 0.56, p = 0.055) and negatively associated with constructive problem-solving (B = −1.81, SE = 0.73, p < 0.05). These results imply that greater treatment effort was expended in the intervention for caregivers who were experiencing more serious difficulties in their caregiving roles.

Differences in financial stipends

We entertained the possibility that attrition rates may have been influenced by the financial stipends provided to caregivers and care recipients. We classified caregivers by whether they had a final assessment (time 4); if so, they were completers. Caregivers who did not have a final assessment were classified as non-completers. A χ2 analysis determined the non-completion rates across the two stipend rates were not significantly different. We then examined potential differences in attrition and stipend amounts within each experimental group. χ2 analyses revealed no differences by stipend amount between completers and non-completers in either the PST or the education-only groups. Finally, we examined stipend rates and the amount of telephone sessions in the PST and education-only control groups. Because the outcome variable, number of sessions, is a count variable and not normally distributed in either group, we conducted a Kruskal–Wallis test comparing the stipend amount on number of sessions completed. The results were again non-significant. Consequently, we found no evidence that the stipend amount was associated with attrition or with participation in the prescribed group experience.

Discussion

Although other work has reported the utility of PST for family caregivers of persons with debilitating health conditions (Grant et al., 2002; Sahler et al., 2005; Wade et al., 2006a), this is the first RCT of any cognitive–behavioral intervention for community-residing family caregivers of women with disabilities. The present study indicates that PST provided in a combination of face-to-face and telephone sessions over 12 months may be effective in lowering the depression reported by family caregivers, regardless of their age and the time they have spent in the caregiver role. Similar to prior research, family caregivers of women with disabilities reported significant declines in depression over time as they received PST (Elliott & Berry, 2009; Elliott et al., 2008; Grant et al., 2002; Rivera, Elliott, Berry, & Grant, 2008). The downward trajectory in depression in response to PST appears to be a linear process (rather than a quadratic one), as evidenced in several other studies (Elliott & Berry, 2009; Elliott et al., 2008; Grant et al., 2002).

Generally, intervention studies indicate that significant gains in overall problem-solving abilities are often associated with decreasing distress (Malouff et al., 2007; Nezu, 2004). Results from the present study imply that PST may significantly enhance a constructive problem-solving style – which is composed of the positive problem orientation and the rational problem-solving skills subscales of the SPSI-R – and these gains accounted for the significant declines in caregiver depression over time. Thus, as caregivers developed greater competence in self-regulation (including heightened motivation for solving problems and in identifying emotions, generally, and in promoting positive moods, specifically) and in the use of rational problem-solving skills, they experienced fewer problems with depressive symptoms. Prior work has documented significant effects of PST on the problem orientation component (e.g., Nezu & Perri, 1989); to our knowledge, the present study is the first to document significant gains in constructive problem-solving styles and demonstrate the association between these changes and corresponding declines in depression response to PST.

Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be considered. All outcome measures relied on self-report instruments and the effects of PST were limited to the self-report measures of depression. We have little insight into the lack of effects on caregiver health and life satisfaction. Only one interventionist provided problem-solving training to caregivers in the treatment condition; we cannot dismiss the possibility of therapist effects in the PST condition. The study relied on a sample composed of individuals who had the interest and capacity to participate in a project that would provide a type of home-based educational program (education-only control group experience; PST), and who were able to access and respond to recruitment materials. Evidence indicates that certain motivational characteristics may distinguish those who participate in an RCT from those who are unwilling to volunteer for this kind of research (West et al., 2008), and these may reflect a small percentage of individuals who are interested in participating in a psychological intervention (Tucker & Reed, 2008). Although randomization ideally provides some degree of control over the possible effects of biases in response to treatment, our ability to generalize to people in general remains circumscribed. The lack of an independent randomization procedure is also a limitation of the current study.

The average scores for the sample on the CES-D measure were lower than cut-off scores that are indicative of clinical levels of depression (scores > 16; Craig & Van Natta, 1978). The relatively lower scores observed in our sample imply that participants may not have been experiencing symptoms typically associated with depressive disorders. Interestingly, our longitudinal design revealed a steady increase in the trajectory of CES-D scores among caregivers in the education-only control group. This finding suggests that many caregivers may experience an increase in distress even when they are routinely receiving educational materials and contacts over a 12-month period. PST and other cognitive–behavioral interventions may be instrumental in preventing increases in caregiver distress.

Finally, it should be noted that there is no “treatment-as-usual” for community-residing family caregivers of women with disabilities; therefore, our education-only group did not provide a true “control” group condition. In many community-based intervention studies of persons with chronic health conditions it is extremely difficult to construe and provide a true control group experience in an RCT and this factor may compromise our ability to study and detect meaningful differences between groups (Elliott, 2007).

Despite these limitations, the present study provides further evidence for the use of PST in telehealth applications (Elliott et al., 2008; Grant et al., 2002; Wade et al., 2006b). The study also underscores the potential value of collaborative partnerships with caregivers that place a unique focus on specific problems identified by each caregiver in each session (Elliott & Shewchuk, 2000). Telephone counseling may reinforce this sense of partnership. It may circumvent obstacles to counseling provided in outpatient clinics such as client physical disability and associated mobility impairments, social anxiety, geographical isolation, and time constraints (Haas, Benedict, & Kobos, 1996). Analysis of consumer opinions about telephone counseling indicate that people find the convenience, accessibility, sense of control over the sessions, and lack of inhibition during sessions to be helpful aspects of telephone counseling (Reese, Conoley, & Brossart, 2006). Other work clearly indicates that community-residing recipients of telephone counseling are satisfied with the experience and believe it “…helped them improve their lives” (Reese, Conoley, & Brossart, 2002, p. 239). Moreover, telephone counseling appears to be as effective as outpatient office visits in reducing problems experienced by families, and families prefer telephone counseling over the traditional office visit (and it should be noted, not surprisingly, that clinicians prefer traditional office visits; Glueckauf et al., 2002).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development (# R01HD37661), from the National Institute for Disability and by Rehabilitation Research, TBI Model System Program (H133A020509), and from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – National Center for Injury Prevention and Control to the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Injury Control Research Center (R49/CE000191). The contents of the study are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. The authors express appreciation to Patricia Rivera, Gary Edwards, Russ Fine, Tom Novack, Dennis Adams, Kim Oswald, Katrina Gilbert, Morgan Hurst and Tarah Newsham for their contributions at various stages of the project.

References

- Arno PS. Economic value of informal caregiving. Proceedings of the Care Coordination and Caregiving Forum, National Institutes of Health and Department of Veterans Affairs; January 25–27, 2006; Bethesda, MD. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J, Elliott T, Rivera P. Resilient, undercontrolled, and overcontrolled personality prototypes among persons with spinal cord injury. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;89:292–302. doi: 10.1080/00223890701629813. Scopus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. Addressing the caregiver crises. [accessed February 8, 2008];Preventing Chronic Disease. 2008 5(1):1–2. http://www.cdc.gov/issues/2008/jan/07_0162.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau N, Daler S, Andre JM, Patris A. Inter-rater agreement of two functional independence scales: The Functional Independence Measure (FIMSM) and a subjective uniform continuous scale. Disability and Rehabilitation. 1994;16(2):63–71. doi: 10.3109/09638289409166014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig T, Van Natta PA. Current medication use in symptoms of depression in a general population. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;135:1036–1039. doi: 10.1176/ajp.135.9.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons R, Larsen R, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds TA, Martin DP, Stolov WC, Deyo RA. A validation of the functional independence measure and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 1993;74:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90119-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelan K, Falik M, DesRoches C. Caregiving: challenges and implications for women’s health. Women’s Health Issues. 2001;11:185–200. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(01)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelan K, Hill CA, Hoffman C, Scoles K, Hoffman PH, Levine C, et al. Challenged to care: informal caregivers in a changing health system. Health Affairs. 2002;21:222–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreer L, Elliott T, Shewchuk R, Berry J, Rivera P. Family caregivers of persons with spinal cord injury: predicting caregivers at risk for probable depression. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2007;52:351–357. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.52.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu A. Problem-solving therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Maydeu-Olivares A. Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R): technical manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multihealth Systems; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Maydeu-Olivares A. Social problem solving: theory and assessment. In: Chang E, D’Zurilla TJ, Sanna LJ, editors. Social problem solving: theory, research, and training. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T. Registering randomized clinical trials and the case for CONSORT. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:511–518. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.6.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Berry JW. Brief problem-solving training for family caregivers of persons with recent-onset spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65 doi: 10.1002/jclp.20527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Hurst M. Social problem solving and health. In: Walsh WB, editor. Biennial review of counseling psychology. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Press; 2008. pp. 295–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Shewchuk RM. Problem solving therapy for family caregivers of persons with severe physical disabilities. In: Radnitz C, editor. Cognitive-behavioral interventions for persons with disabilities. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 2000. pp. 309–327. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Shewchuk R, Richards JS. Family caregiver social problem-solving abilities and adjustment during the initial year of the caregiving role. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48:223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Brossart D, Berry JW, Fine PR. Problem-solving training via videoconferencing for family caregivers of persons with spinal cord injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:1220–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine M, Asch A. Disability beyond stigma: social interaction, discrimination, and activism. Journal of Social Issues. 1988;44:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glueckauf RL, Fritz S, Ecklund-Johnson E, Liss H, Dages P, Carney P. Videoconferencing-based family counseling for rural teenagers with epilepsy: phase 1 findings. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2002;47:49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Granger C, Cotter AC, Hamilton B, Fiedler RC. Functional assessment scales: a study of persons after stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1993;74:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J, Elliott T, Weaver M, Bartolucci A, Giger J. A telephone intervention with family caregivers of stroke survivors after hospital discharge. Stroke. 2002;33:2060–2065. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020711.38824.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J, Elliott T, Weaver M, Glandon G, Giger J. Social problem-solving abilities, social support, and adjustment of family caregivers of stroke survivors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2006;87:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas LJ, Benedict JG, Kobos JC. Counseling by telephone: risks and benefits for psychologists and consumers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1996;27:154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna WJ, Rogovsky B. Women with disabilities: two handicaps plus. Disability. Handicap & Society. 1991;6(1):49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. Mahwah, NJ: LEA; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes RB, Robinson-Whelen S, Taylor H, Petersen N, Nosek M. Characteristics of depressed and nondepressed women with physical disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;86:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The future of disability in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Elliott T, Neilands T, Morin SF, Chesney MA. A social problem-solving model of adherence to HIV medications. Health Psychology. 2006;25:355–363. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok OM, Underhill A, Berry JW, Luo W, Elliott T, Yoon M. Analyzing longitudinal data with multilevel models: an example with individuals living with lower extremity intra-articular fractures. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2008;53:370–386. doi: 10.1037/a0012765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Hayes AM, Feldman GC. Some methodological and statistical issues in the study of change processes in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychological Review. 2007;27:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis Applied Social Research Methods Series. Vol. 49. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lollar DE, Crews J. Redefining the role of public health in disability. Annual Review of Public Health. 2003;24:195–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson E, Schutte N. The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metlife Mature Market Institute. Miles away: The Metlife study of long-distance caregiving. Westport, CT: Metlife Mature Market Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Metlife Mature Market Institute. The Metlife caregiving cost study: productivity losses to US businesses. Westport, CT: Metlife Mature Market Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission for Quality Long-Term Care. From isolation to integration: recommendations to improve quality in long-term care. Washington, DC: National Commission for Quality Long-Term Care; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu A. Problem solving and behavior therapy revisited. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu AM, Perri MG. Social problem solving therapy for unipolar depression: an initial dismantling investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezu AM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts P. Project Genesis: assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:1036–1048. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek MA, Hughes RB. Psychosocial issues of women with physical disabilities: the continuing gender debate. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 2003;46:224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Nosek MA, Howland C, Rintala DH, Young ME, Chanpong MS. National study of women with physical disabilities: final report. Sexuality and Disability. 2001;19:5–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nosek MA, Hughes RB, Swedlund N, Taylor HB, Swank P. Self-esteem and women with disabilities. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:1737–1747. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish SL, Pomeranz-Essley A, Braddock D. Family support in the United States: financing trends and emerging initiatives. Mental Retardation. 2003;41(3):174–187. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2003)41<174:FSITUS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. The psychology of physical symptoms. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reese RJ, Conoley CW, Brossart DF. Effectiveness of telephone counseling: a field-based investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Reese RJ, Conoley CW, Brossart DF. The attractiveness of telephone counseling: an empirical investigation of client perceptions. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2006;84:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera P, Elliott T, Berry J, Shewchuk R, Oswald K, Grant J. Family caregivers of women with physical disabilities. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2006;13:431–440. doi: 10.1007/s10880-006-9043-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera P, Elliott T, Berry J, Oswald K, Grant J. Predictors of caregiver depression among community-residing families living with traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera P, Elliott T, Berry J, Grant J. Problem-solving training for family caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2008;89:931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahler O, Fairclough D, Phipps S, Mulhern R, Dolgin M, Noll R, et al. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: report of a multisite randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:272–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shewchuk R, Elliott T. Family caregiving in chronic disease and disability: implications for rehabilitation psychology. In: Frank RG, Elliott T, editors. Handbook of rehabilitation psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2000. pp. 553–563. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE. Mediation analyses in longitudinal studies. Presentation at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the. New York: Association for Psychological Science (APS); 2006. May, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith HM. Psychological needs of older women. Psychological Services. 2007;4:277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Surgeon General’s Workshop on Women’s Mental Health. Workshop Report (November 30-December 1, 2005. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:224–228. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Reed G. Evidentiary pluralism as a strategy for research and evidence-based practice in rehabilitation psychology. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2008;53:279–293. doi: 10.1037/a0012963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uniform Data Set For Medical Rehabilitation. Guide for the use of the uniform data set for medical rehabilitation, Version 5.0. Buffalo, NY: State University of New York at Buffalo Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; Healthy people 2010. 2000 http://www.health-gov.healthypeople Available at.

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan J. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Young H, Zhang J. Is caregiving a risk factor for illness? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wade SL, Carey J, Wolfe CR. An online family intervention to reduce parental distress following pediatric brain injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006a;74:445–454. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade SL, Carey J, Wolfe CR. The efficacy of an online cognitive-behavioral family intervention in improving child behavior and social competence in pediatric brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2006b;51:179–189. [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Duan N, Pequegnat W, Gaist P, Des Jarlais DC, Holtgrave D, et al. Alternatives to the randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1359–1366. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.124446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]