Abstract

Little is known regarding killing activity of vancomycin against methicillin (meticillin)-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in pneumonia since the extent of vancomycin penetration into epithelial lining fluid (ELF) has not been definitively established. We evaluated the impact of the extent of ELF penetration on bacterial killing and resistance by simulating a range of vancomycin exposures (24-h free drug area under the concentration-time curve [ƒAUC24]/MIC) using an in vitro pharmacodynamic model and population-based mathematical modeling. A high-dose, 1.5-g-every-12-h vancomycin regimen according to American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines (trough concentration, 15 mg/liter) with simulated ELF/plasma penetration of 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, or 100% (ƒAUC24/MIC of 0, 70, 140, 210, 280, or 350) was evaluated against two agr-functional, group II MRSA clinical isolates obtained from patients with a bloodstream infection (MIC = 1.0 mg/liter) at a high inoculum of 108 CFU/ml. Despite high vancomycin exposures and 100% penetration, all regimens up to a ƒAUC24/MIC of 350 did not achieve bactericidal activity. At regimens of ≤60% penetration (ƒAUC24/MIC ≤ 210), stasis and regrowth occurred, amplifying the development of intermediately resistant subpopulations. Regimens simulating ≥80% penetration (ƒAUC24/MIC ≥ 280) suppressed development of resistance. Resistant mutants amplified by suboptimal vancomycin exposure displayed reduced rates of autolysis (Triton X-100) at 72 h. Bacterial growth and death were well characterized by a Hill-type model (r2 ≥ 0.984) and a population pharmacodynamic model with a resistant and susceptible subpopulation (r2 ≥ 0.965). Due to the emergence of vancomycin-intermediate resistance at a ƒAUC24/MIC of ≤210, exceeding this exposure breakpoint in ELF may help to guide optimal dosage regimens in the treatment of MRSA pneumonia.

Nosocomial pneumonia remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. Recently the American Thoracic Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (ATS/IDSA) (1) proposed vancomycin trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter for health care- and ventilator-associated (HAP and VAP) methicillin (meticillin)-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pneumonia. This recommendation is derived from evidence suggesting that the vancomycin 24-h area-under-the-concentration-time-curve-to-MIC (AUC/MIC) ratio of ≥350 is predictive of cure in patients with S. aureus pneumonia and recent concerns regarding vancomycin's antistaphylococcal activity, such as the MIC “creep,” low rate of killing, and increasing reports of treatment failure (14, 26, 31, 32). However, there has been significant debate as to whether high-dose vancomycin is beneficial, since some studies have shown that greater exposure is not correlated with a more favorable hospital outcome and is associated with increased nephrotoxicity in patients receiving high-dose vancomycin regimens (9, 11, 22).

Additionally, little is known regarding the degree of penetration of vancomycin into epithelial lining fluid (ELF) from plasma. Although an earlier study by Lamer et al. (19) provided evidence that vancomycin penetrates poorly into ELF (free vancomycin in ELF/plasma was less than 30%), a recent study by G. L. Drusano et al. (7a) suggests that ELF penetration may be higher (free vancomycin in ELF/plasma was approximately 100%). Adding to this discrepancy is the lack of information regarding vancomycin's killing activity and ability to suppress resistance at clinically achievable concentrations at the site of infection and the relationship between the early physiologic changes in S. aureus that occur due to suboptimal exposure.

The objective of this investigation was to simulate human concentration-time profiles of vancomycin in ELF and determine the proclivity toward developing reduced glycopeptide susceptibility, tolerance, and phenotypic alterations using an in vitro pharmacodynamic model of MRSA infection and mathematical modeling.

(This work was presented in part at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Chicago, IL, September 2007.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

Two clinical MRSA isolates (S203 and S204) obtained from patients with bloodstream infections at the Buffalo VA Health System of Western New York in 2003 were evaluated. All studies were conducted in accordance with the institutional review board at the University at Buffalo and the VA Western New York Healthcare System. Patient isolates were exempt from enrollment. Both isolates belonged to accessory gene regulator (agr) group II and were delta-hemolysin positive. Delta-hemolysin production was used as a surrogate marker of agr function using methodology described previously (30, 39).

Antibiotics and medium.

Vancomycin analytical-grade powder was commercially purchased (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO). Fresh solutions were prepared in the morning prior to each experimental run. Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) supplemented with calcium (25 mg/liter) and magnesium (12.5 mg/liter) was utilized for susceptibility testing. Brain heart infusion (BHI) agar and BHI broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) were used for all in vitro model experiments. Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood agar (TSA II; Becton-Dickinson Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) was utilized for quantification of bacteria.

Determining alterations in MIC.

Vancomycin MICs were determined by broth microdilution according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute in quadruplicate prior to all in vitro model experiments. Quantitative cultures were determined on BHI agar plates to allow detection of the susceptible population and on BHI agar containing 2, 4, or 6 mg/liter vancomycin to quantify the resistant subpopulations at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. Colonies were enumerated after 48 h of incubation at 37°C and plotted as a function of time for both isolates and drug regimens tested using the SigmaPlot 9 software program. Changes in MICs were determined using the vancomycin Etest strip, which were placed on BHI plates inoculated with suspensions adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard to confirm the emergence of resistance. The intersection of the elliptical inhibition zone and the E-strip was read according to the Etest manufacturer's instructions.

IVPM.

An in vitro pharmacodynamic model (IVPM) consisting of a one-compartment 500-ml glass chamber (working model volume, 250 ml broth) with multiple ports for the removal of BHI broth, delivery of antibiotic, and collection of bacterial and antimicrobial samples was utilized (39). Briefly, overnight cultures of MRSA isolates were diluted in fresh BHI broth and adjusted to a 1.0 McFarland turbidity. The suspension was added to BHI broth in the IVPM, yielding a final volume of 250 ml and a starting inoculum over 108 CFU/ml. Serial samples were taken at 0 (predose), 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, 28, 32, 48, 52, 56, and 72 h to assess viable counts. Antimicrobial carryover was minimized by centrifuging the bacterial samples at 10,000 × g for 5 min and then reconstituting them with sterile normal saline to their original volumes, followed by subsequent serial dilution (10- to 100,000-fold). Viable bacterial counts were determined by plating 100-μl samples of each diluted sample on BHI agar, using an automated spiral dispenser (Automatic Spiral Plater; Microbiology International, Rockville, MD). Plated samples were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and colony counts (log10 CFU/ml) were determined by using an automated bacterial colony counter (aCOLyte; Synbiosis, Frederick, MD). Colony count (log10 CFU/ml) data were plotted as a function of time for all tested drug regimens for each isolate. Bactericidal activity at 72 h was defined as a 99.9% reduction in colony counts compared to the starting inoculum.

Simulated regimens.

A vancomycin high-dose regimen of 1.5 g every 12 h (q12h) was selected based on a trough concentration of 15 mg/liter (total vancomycin concentration in plasma) as recommended by ATS/IDSA guidelines for HAP/VAP and the IDSA/American Society of Health-System Pharmacists/Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists vancomycin therapeutic monitoring guidelines (1, 28) with the following pharmacokinetic values: total plasma maximum drug concentration (Cmax)/MIC of 60 mg/liter, total plasma minimum drug concentration (Cmin)/MIC of 15 mg/liter, and total plasma AUC/MIC from 1 to 24 h (MIC0-24) of 778 based on a half-life of 6 h. Using a protein binding level of 55% for vancomcyin in plasma, this yields the following values for this regimen: free drug Cmax (ƒCmax)/MIC of 27, free drug Cmin (fCmin)/MIC of 6.8, and free drug AUC (ƒAUC)/MIC0-24 of 350 using the linear trapezoidal rule. This regimen was then divided according to percent penetration into ELF from plasma according to the following studies characterizing vancomycin pharmacokinetics.

Recent data by Drusano et al. (47th ICAAC, A-2151, 2007) show a high extent of penetration of approximately 100% for vancomycin into ELF (total drug AUC in ELF divided by ƒAUC in plasma), whereas a low penetration of 20% (based on concentration ratios) was reported by Lamer et al. (19). Therefore, to consider a wide range of ELF/plasma penetration ratios, which may also be affected by the disease state, we simulated penetration into ELF (ƒAUC24/MIC in parentheses) of 20% (70), 40% (140), 60% (210), 80% (280), or 100% (350) of the 1.5-g q12h regimen, which is shown in Table 1. All simulated exposure profiles were administered q12h throughout the 72-h period of the study. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of vancomycin in ELF simulated in an in vitro pharmacodynamic modela

| fAUC/ MIC0-24c | % Penetration (ELF/plasma)b | fCmax (mg/liter) | fCmin (mg/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 350 | 100 | 27 | 6.8 |

| 280 | 80 | 21.6 | 5.4 |

| 210 | 60 | 16.2 | 4.1 |

| 140 | 40 | 10.8 | 2.7 |

| 70 | 20 | 5.4 | 1.4 |

A vancomycin regimen of 1,500 mg q12h was simulated, based on a total trough concentration in plasma of 15 mg/liter (assuming a protein binding level of 55%) according to ATS/IDSA and IDSA/ASHP/SIDP guidelines (1, 28).

The extent of penetration is based on the simulated vancomycin AUC in ELF divided by the AUC in plasma.

All simulated regimens were administered q12h.

Autolysis.

Autolysis profiles using Triton X-100 were determined spectrophotometrically, as described previously (30). Briefly, MRSA isolates after a 72-h vancomycin exposure in the IVPM were evaluated for autolysis. Samples were pelleted using a centrifuge and washed with ice-cold Tris-EDTA (4°C). Pellets were resuspended in Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.2 (0.05 M) with 0.05% Triton X-100. Suspensions were adjusted to 0.5 optical density at 620 nm (OD620) and incubated at 37°C for 8 h. Samples were obtained every 2 h to measure OD620s up to 8 h. The ratio of the area under the absorbance curve over 8 h for the drug-exposed isolates (AUCdrug absorbance) compared to the AUC for no change (100%) in absorbance over 8 h (AUCstasis absorbance = OD620 × 8 h) was calculated. To quantify the effect of various vancomycin dosage regimens on the extent of autolysis, the “extent of autolysis” was calculated as AUCdrug absorbance/ AUCstasis absorbance.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Samples for pharmacokinetic analysis were obtained at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, 28, 32, 48, 52, 56, and 72 h. Vancomycin concentrations were determined by standard agar diffusion bioassay procedures using Mueller-Hinton agar with Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341 as an indicator organism (38). Standards and samples were tested in quadruplicate using blank -in. disks saturated with 20 μl of the solution. Concentrations of 0.5 to 30 mg/liter were used as standard curves for vancomycin. The limit of detection for vancomycin was 0.75 mg/liter. The peak concentration (Cmax), trough concentration (Cmin), and elimination half-life (t1/2) were calculated from the concentration-time profiles. The AUC0-24 was calculated using the linear trapezoidal method in the WinNonlin software program (version 5.0.1; Pharsight, Cary, NC).

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analysis. (i) Area-based method.

An integrated PK/PD area measure (log ratio area) was applied to all CFU data to quantify the drug effect as shown in equation 1, as described previously (40):

|

(1) |

AUCFU (area under the CFU-versus-time curve) was calculated on a linear scale from 0 to 72 h using the linear trapezoidal rule in WinNonlin. Using nonlinear regression, a four-parameter concentration-effect Hill-type model was fit to the effect parameter in the Systat (Richmond, VA) software program (version 11) as described previously (40):

|

(2) |

where the dependent variable (E) is the log ratio area, E0 is the effect measured at a drug concentration of zero, Emax is the maximal effect, EC50 is the fAUC/MIC ratio for which there is 50% maximal effect, and H is the Hill or sigmoidicity constant. The parameters of this Hill equation were estimated using maximum-likelihood methods.

(ii) Population PK/PD modeling.

Candidate models were simultaneously fit to all CFU-versus-time data of both strains in the NONMEM VI software program (level 1.2; NONMEM Project Group, Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD) with the first-order conditional-estimation methods and an additive error model on a logarithmic scale. Model discrimination was based on the individual curve fits, NONMEM's objective function, and the model stability during estimation.

The drug effect was modeled as either inhibition of growth or stimulation of bacterial killing. Models with one, two, or three subpopulations of different susceptibilities for each strain were considered.

Bacterial growth was described by a saturable growth function as described previously (24). We reparameterized this growth model and estimated the shortest growth t1/2 at low bacterial concentrations (t1/2,low CFU/ml) and the maximum population size (POPmax). The maximum growth rate constant (kg) at low CFU/ml, the maximum velocity of bacterial growth (VGmax; unit, CFU/ml/h), and the bacterial concentration (CFUm) associated with 50% of VGmax can be calculated from t1/2,low CFU/ml, POPmax, and first-order natural death rate constant, kd:

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

These equations were derived from the steady-state solution of the model from Meagher et al. (24) in the absence of an antibiotic. To describe a lower rate of growth of the resistant subpopulation than of the susceptible subpopulation, the ratio of VGmax for the resistant subpopulation divided by VGmax for the susceptible subpopulation was described by frVGmax,R. A transit compartment approach was used to describe a slower initial rate of bacterial growth. The mean transit time for the lag process was described by MTTlag. This approach is comparable to previous implementations of lag time (37).

In the final model, inhibition of bacterial growth for the susceptible (INHgrowth,S) and resistant (INHgrowth,R) subpopulation by the vancomycin concentration (CDrug) was described by different drug concentrations causing 50% of maximal inhibition for the susceptible (IC50,S) and resistant (IC50,R) subpopulations as described previously (4, 7, 8):

|

(6) |

This yields the following set of (differential) equations for a model with two subpopulations (ADrug, concentration of vancomycin in the system; CFUS,lag [CFUR,lag], concentration of susceptible [resistant] bacteria in the lag compartment; CFUS [CFUR], concentration of replicating susceptible [replicating resistant] bacteria; CFUall, bacterial concentration of all subpopulations):

|

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

The total initial inoculum and the initial inoculum of the resistant population (CFUoR) were estimated, and the initial inoculum of the susceptible population (CFUoS) was calculated as the difference in the former two estimates. Initial conditions for equations 7, 10, and 11 were zero. A clearance (CL) of 0.5 ml/min and volume of distribution (V) of 250 ml yield an elimination half-life (rate constant, kel) of approximately 6 h. Loss of bacteria due to washout from the unfiltered system was described by kel.

RESULTS

Impact of escalating vancomycin exposure on total and resistant bacterial populations.

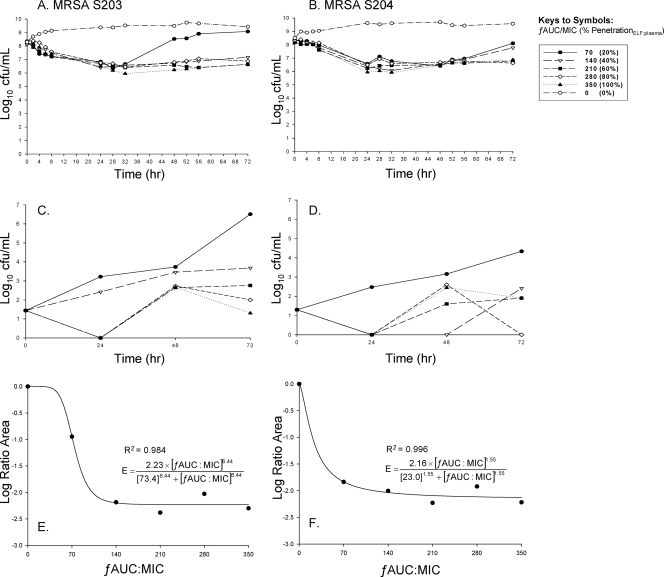

The vancomycin MICs of MRSA S203 and S204 were 1.0 mg/liter. Vancomycin displayed bacteriostatic activity against both isolates in all tested regimens, with maximal reductions of 1.7 log10 CFU/ml from the baseline at all exposures up to a ƒAUC24/MIC of 350 (100% penetration) at 72 h (Fig. 1A and B). Regrowth was present at low exposures, ƒAUC24/MIC of 70 (20% penetration), for both clinical isolates. Bacterial counts from nadir to 72 h increased for regimens with ƒAUC24/MIC of 70 by 2.73 log10 CFU/ml for S203 and by 1.53 log10 CFU/ml for S204 (Fig. 1A and B). Increasing numbers of resistant mutants appeared at lower simulated exposures of vancomycin in ELF, since significant growth was present on vancomycin plates containing 2 mg/liter in agar (Fig. 1C and D). Amplification of resistant mutants was observed at a ƒAUC24/MIC as high as 210 (60% penetration). Resistant mutants exceeded 60% of the total population at 72 h, with growth up to 6.5 log10 CFU/ml on vancomycin plates with 2 mg/liter after vancomycin exposure. All exposures amplified resistant mutants growing on agar with 2 mg/liter vancomycin, while only lower exposures of ƒAUC24/MIC of ≤140 amplified intermediately resistant mutants displaying growth on 4 and 6 mg/liter of vancomycin containing agar.

FIG. 1.

The killing activities of simulated vancomycin regimens in an in vitro infection model profiling the total population over time versus S203 or S204 (A and B) or a resistant population growing on vancomycin 2-mg/liter BHI agar (C and D). The pharmacodynamic relationship between the log ratio area and the ƒAUC/MIC (R2 represents the coefficient of determination) is shown in the bottom panels (E and F).

Interestingly, for both MRSA isolates, exposure to a ƒAUC24/MIC of ≥280 (80% penetration) suppressed the development of resistance throughout the 72-h experiment, and no growth was present on 4 and 6 mg/liter of vancomycin-containing agar. Postexposure MICs at 72 h for the ƒAUC 0, 70, 140, 210, 280, and 350 regimens were 1.0, 6.0, 6.0, 6.0, 6.0, and 2.0 mg/liter for S203 and 1.0, 6.0, 6.0, 4.0, 2.0, and 2.0 mg/liter for S204, respectively. Therefore, under selective drug pressure, all exposure profiles (except after exposure to a ƒAUC/MIC of 350 and a ƒAUC/MIC of 280 for S204) demonstrated the occurrence of vancomycin-intermediate resistance by 72 h.

Modeling drug effect on bacterial growth and death and pharmacokinetics.

Analysis of pharmacodynamics revealed excellent model fits (r2 > 0.98) of the data to the Hill-type model, since vancomycin killing occurred in an exposure-dependent manner against both strains (Fig. 1E and F).

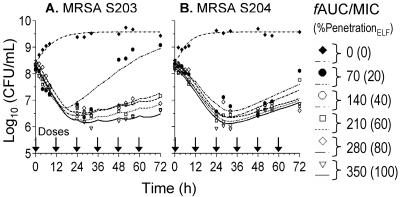

The population PK/PD analysis showed that models which implemented the drug effect as inhibition of growth performed better than models that specified the drug effect as stimulation of death. A model with three bacterial subpopulations provided better curve fits for one of the six dosage regimens for one of the two strains. The three-subpopulation model provided in part physiologically unreasonable parameter estimates (extremely low IC50,S), and this model was less robust than a model with two subpopulations. Since the simpler model provided excellent curve fits (Fig. 2) for both strains, we selected the model with two subpopulations as the final model. A linear regression of the observed versus the individual [population] fitted log10 (CFU/ml) yielded a slope of 1.004 [0.996], intercept of −0.031 [+0.014], and r2 value of 0.965 [0.923] for the model with two subpopulations.

FIG. 2.

Observed and fitted bacterial counts for simulated vancomycin exposures in ELF against S203 (A) or S204 (B).

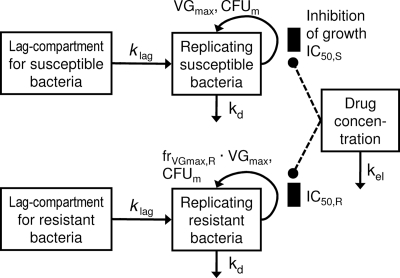

Figure 3 shows the structure of the final model. For strain S204, both the susceptible and resistant subpopulations were estimated to have higher IC50 values than the respective population of strain S203 (Table 2). However, the growth half-life of the resistant population was longer for strain S204 (133 min) than for strain S203 (100 min). Parameter estimates were reasonably precise (Table 2). Since the lowest studied trough concentration was approximately fourfold higher than the IC50,S values and since the IC50,R values were (notably) higher than the highest studied peak concentration, standard errors for the IC50 terms were larger. Standard curves for vancomycin bioassays were linear over the concentration between 2 and 25 mg/liter (r2 = 0.882) when the standards were prepared in BHI medium. The lower limit of detection for vancomycin was 0.75 mg/liter. Observed pharmacokinetic parameters were within 20% of targeted values.

FIG. 3.

Structure of the final model with a susceptible and a resistant subpopulation describing the effect of vancomycin as inhibition (IC50,S and IC50,R) of the saturable growth function for each subpopulation. The lag compartments are linked to the compartments for replicating cells via a first-order rate constant (klag = 1/MTTlag). Arrows for loss of bacteria due to washout from the unfiltered in vitro model are not shown. See Materials and Methods for further explanation of parameters.

TABLE 2.

Estimates for final population PK/PD model for vancomycin against MRSA strains S203 and S204

| Parameter | Symbol and/or unit | Estimate (SE [%])

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA S203 | MRSA S204 | ||

| Initial inoculum of total population | Log10 CFUo | 8.34 (0.8)a,b | 8.34 (0.8)a,b |

| Initial inoculum of resistant population | Log10 CFUoR | 5.91 (5)a | 5.55 (9)a |

| Maximum population size | Log10 POPmax | 9.98 (0.9)a | 9.98 (0.9)a |

| Mean transit time for growth lag | MTTlag (h) | 0.01 (fixed)c | 1.96 (45) |

| Shortest growth half-life at low bacterial concentrations for susceptible population | t1/2,low CFU/ml (min) | 77.5 (17)d | 61.4 (32)d |

| Shortest growth half-life at low bacterial concentrations for resistant population | t1/2,low CFU/ml,R (min) | 100e | 133e |

| Relative maximum velocity of growth for resistant compared to susceptible populations | frVGmax,R | 0.773 (16) | 0.460 (36) |

| Natural death rate constant | kd (h−1) | 0.161 (27) | 0.119 (32) |

| Concn causing 50% of inhibition of growth for the susceptible population | IC50,S (mg/liter) | 0.167 (143) | 0.296 (89) |

| Concn causing 50% of inhibition of growth for the resistant population | IC50,R (mg/liter) | 39.3 (32) | 200 (89) |

| SD of additive residual error on log10 scale | SDerr | 0.208 (13)f | 0.208 (13)f |

Population mean was shared between the two strains.

The standard deviation for the variability of log10 (CFUo) between runs was estimated to be 0.15 (69% standard error).

The MTTlag was estimated to be very small and was eventually fixed to 0.01 h for strain S203.

The coefficient of variation for the variability of growth half-life between runs was estimated to be 4.0% (63% standard error).

Calculated based on t1/2,low CFU/ml and frVGmax,R. The t1/2,low CFU/ml,R was not an estimated model parameter.

Estimate for residual error was shared between the two strains.

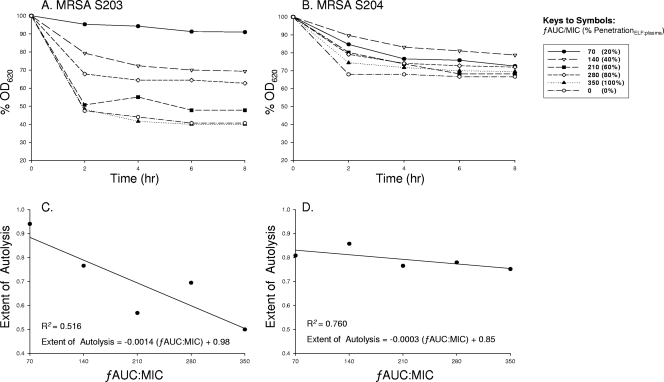

Alterations in autolysis secondary to vancomycin exposure.

Resistant mutants displayed defective autolysis profiles after suboptimal exposure to vancomycin (Fig. 4A and B). The mutant strains (MIC ≥ 2 mg/liter) showed marked autolysis inhibition. At the 2-h time point, subsequent differences of reduction in initial absorbance between a ƒAUC/MIC of 350 and a ƒAUC/MIC of 70 for S203 and S204 were 46.95 and 10.24, respectively. Interestingly, a linear relationship between vancomycin exposure (ƒAUC/MIC) and the extent of autolysis of S. aureus was found (Fig. 4C and D).

FIG. 4.

Postexposure isolates of MRSA S203 (A) or MRSA S204 (B) for each vancomycin regimen simulated (as shown in the key to the symbols) in the IVPM were obtained at 72 h and subsequently evaluated for differences in autolysis profiles over 8 h. The pharmacodynamic relationship between the extent of autolysis and the ƒAUC/MIC for S203 (C) or for S204 (D) is shown.

DISCUSSION

Despite more than 50 years of clinical use of vancomycin, knowledge regarding the degree of penetration into ELF has been lacking, with only two studies, limited by a small number of patients and single-time-point pharmacokinetic comparisons, addressing this issue (5, 19, 35). Recently published guidelines (1, 28, 38) support the notion of poor vancomycin penetration into ELF, citing that vancomycin is to be dosed to achieve high trough levels of 15 to 20 mg/liter for MRSA pneumonia, which has been adopted by some clinicians for all infection sources, with some institutions utilizing vancomycin doses of >4 g/day (22, 25). Although increased exposure of vancomycin is driven by the perceived poor penetration of vancomycin in pneumonia and the necessity of achieving a greater drug exposure in ELF, nephrotoxicity has been reported at these high exposures (9, 12, 16, 22). A recent pharmacokinetic study by Drusano et al. (47th ICAAC, A-2151, 2007) suggests that vancomycin penetration into ELF compared to that into plasma may indeed be higher than once anticipated, at approximately 100% of the free drug AUC in plasma. Therefore, much still remains unknown regarding the impact of escalating dose intensity and the selection of optimal dosage regimens in MRSA pneumonia.

The findings of the present study suggest that guideline-recommended dosing regimens of vancomycin with high-dose intensity (1, 28), even under situations of 100% penetration into ELF, may not provide the optimal exposure necessary to achieve bactericidal activity. Even more importantly, under situations of low penetration against a high bacterial inoculum of MRSA, the propensity to develop resistant mutants of S. aureus may be amplified. A high bacterial density of 108 CFU/ml was employed in this study to simulate MRSA infection in pneumonia given that the inoculum size influences vancomycin pharmacodynamics (20, 20a, 38). While decreased killing of a higher density of organisms is perhaps intuitive, the lack of activity at high inocula may also be explained by a propensity for a heterogeneous inoculum to harbor resistant mutants which are amplified secondary to drug exposure (36). This is particularly important if the initial inoculum exceeds the inverse of the mutation frequency. (15) We determined that there was amplification of resistant subpopulations secondary to low vancomycin penetration and exposure in ELF against this inoculum. The time course of bacterial killing and regrowth of resistant bacteria was well characterized by the proposed population PK/PD model. Importantly, the IC50 of the resistant subpopulation was estimated to be notably above the highest simulated unbound peak concentration. These findings may potentially explain the high rate of failure of vancomycin monotherapy in infections associated with high bacterial density, such as pneumonia and endocarditis (11, 21, 26, 32).

The current study also highlights the recent discussion surrounding AUC/MIC targets and breakpoints for vancomycin. The ATS/IDSA and recent American Society of Health-System Pharmacists/IDSA/Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists vancomycin therapeutic monitoring guidelines recommend trough levels for vancomycin of 15 to 20 mg/ml and an AUC/MIC ratio of ≥400 as the optimal serum concentration target (1, 28). Therefore, to achieve these targets in vitro, we simulated a 1.5 g q12h regimen and the following pharmacokinetic parameters in plasma: ƒAUC/MIC ratio of 350, an ƒCmax/MIC ratio of 27 mg/liter, and an ƒCmin/MIC ratio of 6.8 mg/liter. Accounting for vancomycin protein binding (55%), we simulated free-drug concentrations, which can be extrapolated to a total AUC/MIC ratio of approximately 778, a total Cmax/MIC ratio of 60 mg/liter, and a total Cmin/MIC ratio of 15 mg/liter, in following the recommendations of the IDSA. Interestingly, although the current study utilized two MRSA isolates with a MIC of 1 mg/liter, if the MRSA strain selected displayed a MIC of 2 mg/liter, this exposure would decrease to an AUC/MIC of 389, which is below the recommended exposure breakpoint of 400. Furthermore, in situations of poor penetration (20%) into ELF, the IDSA/ATS-recommended regimen of a plasma trough concentration of 15 mg/liter would yield a free ELF trough concentration of 1.4 mg/liter, which may explain the rapid development of heterogeneous resistance in our in vitro model at this extent of penetration. Additionally, these data are supported by clinical data by Hidayat et al. (9), who determined that even when vancomycin trough concentrations of 15 to 20 mg/liter were obtained, a significantly higher mortality rate was observed with patients infected with MRSA pneumonia or bacteremia with MICs of 1.5 to 2 mg/liter than with patients infected with low-MIC strains (≤1 mg/liter). Taken together with vancomycin's association with nephrotoxicity at high doses (22), the development of resistance in situations of poor ELF penetration as shown in the present study suggests that the use of combination therapy or antibiotics other than vancomycin may be warranted in MRSA pneumonia.

Although the precise mechanism in S. aureus leading to vancomycin-intermediate resistance still remains unclear, alterations in cell morphology and autolysis and global transcriptional changes involving the accessory gene regulator (agr) system have been proposed (6, 10, 13, 30, 33). Specifically, alterations in the autolytic pathway have been associated with the development of vancomycin-intermediate resistance: inhibition of the autolytic pathway through the blockage of murein hydrolases and mutations in the vraR operon, a two-component system which impacts cell wall synthesis, have been proposed as potential mechanisms (2, 17, 18, 27, 34). Building upon these findings, our results are the first to demonstrate a PK/PD, dose-response relationship for vancomycin dose intensity and autolysis: lower vancomycin exposures (ƒAUC/MIC) resulted in a lesser extent of autolysis in S. aureus from bloodstream infection. These findings reveal that suboptimal vancomycin dosing or penetration in ELF may be associated with early phenotypic alterations correlated with the development of vancomycin-intermediate resistance. This is especially important in situations of poor antimicrobial penetration against a heterogeneous high bacterial inoculum, where bacterial growth, colonization, and quorum-sensing mechanisms may greatly impact optimal antimicrobial therapy (29, 39, 41).

The current study utilized both Hill-type and population pharmacodynamic models to characterize the pharmacodynamics of vancomycin against MRSA. A sigmoidal Hill-type model using an area-based method has been utilized previously in our laboratory and by other groups to characterize the effect of vancomycin killing against MRSA (23, 40). The drug effect in this model is described as the log ratio of the area under the CFU/ml curve for the treated regimen versus the respective area for the growth control. Therefore, this area-based method has the advantage that it accounts for the entire time course of CFU counts as opposed to the change in viable counts relative to the initial inoculum at a single time point (for example, at 72 h). The Hill-type model showed that the maximal reduction of the area under the CFU-versus-time curve by vancomycin against MRSA was approximately −2 log10, which corresponds to a 99% reduction in the area of organisms. This is in agreement with vancomycin's bacteriostatic pharmacodynamics.

The area-based method provided a robust and readily accessible measure for the time-averaged drug effect in this investigation and is recommended over point-based methods. However, this empirical method cannot predict the time course of bacteria and does not account for the mechanism of bacterial killing, and we are not aware of a rational approach to extend the area ratio method to optimize combination antibiotic regimens. Additionally, the area-based approach takes no account of “shape”: for example, two regimens with similar AUCs of CFU are counted as equivalent even if one drops to a nadir and is returning toward the control level by the end of the experiment and the other drops more slowly but continues throughout the study period. Therefore, the employed population PK/PD modeling approach can simulate the time course of susceptible and resistant bacteria for other than the studied dosage regimens and can implement the mechanism(s) of drug action. Additionally, such mathematical models present the first step toward building models that can describe and simulate the time course of bacterial counts for rational development of antibiotic combination regimens.

The final mathematical model described vancomycin killing as inhibition of growth and contained two subpopulations with different susceptibilities, which is in agreement with the mechanisms of action and resistance for vancomcyin. Of particular interest, the two-subpopulation mathematical model appropriately characterized vancomycin's bacterial killing and mechanisms involved as heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate resistance. For example, since a high fraction of sensitive subpopulations and a low fraction of resistant subpopulations are contained within the initial inoculum of MRSA, it is only until low-level selective drug pressure causes the amplification of resistant subpopulations, which is made evident by the shift in MIC from susceptible to intermediate resistance. VanA-mediated resistance would require a third subpopulation in the mathematical model; however, this rarely develops in the course of vancomycin therapy (3). More-complex mathematical models will need to be developed to describe the phenotypic and genotypic changes that are more likely to occur during longer durations of vancomycin therapy.

The present study had potential limitations, including the use of two clinical isolates, since more geographically diverse clinical isolates are needed in future studies. In addition, since the temporal profile of vancomycin pharmacokinetics in ELF has not been fully elucidated for healthy volunteers or infected patients, the dynamic nature of concentrations in ELF to plasma could be only partly taken into account in the simulated pharmacokinetics in the in vitro models. Although we attempted to account for this by simulating a range of penetration levels from 20 to 100%, between-patient variability in drug disposition may be particularly important for infected patients with lung inflammation, where drug penetration may be higher and the rate of equilibration may be different. Additional studies of animal models of pneumonia are needed to provide additional data to assess the impact of vancomycin penetration into ELF on bacterial killing in vivo, since numerous factors, such as host defense mechanisms and bacterial toxins, may greatly influence antimicrobial pharmacodynamics in vivo.

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential problems associated with suboptimal vancomycin exposures in pneumonia and ultimately may impact vancomycin susceptibility in MRSA. Our data suggest that the use of higher vancomycin exposure profiles, combination therapy, or alternative agents may be necessary to maintain optimal exposures in ELF to suppress the amplification of resistance in MRSA pneumonia. Further in vivo studies are necessary to strengthen the translation of these in vitro findings to humans before our results are applied to clinical practice to guide selection of optimal antimicrobial regimens against MRSA pneumonia.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Interdisciplinary Research Fund. J.B.B. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from Johnson & Johnson.

We thank George Drusano for excellent insight into the pharmacokinetic design of this study. We thank Dung Ngo, Michael Ma, and Christina Hall for excellent technical assistance. We thank Cornelia Landersdorfer for critical comments in reviewing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society. 2005. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171:388-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle-Vavra, S., R. B. Carey, and R. S. Daum. 2001. Development of vancomycin and lysostaphin resistance in a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:617-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang, S., D. M. Sievert, J. C. Hageman, M. L. Boulton, F. C. Tenover, F. P. Downes, S. Shah, J. T. Rudrik, G. R. Pupp, W. J. Brown, D. Cardo, and S. K. Fridkin. 2003. Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1342-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung, P., P. J. McNamara, J. J. Campion, and M. E. Evans. 2006. Mechanism-based pharmacodynamic models of fluoroquinolone resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2957-2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruciani, M., G. Gatti, L. Lazzarini, G. Furlan, G. Broccali, M. Malena, C. Franchini, and E. Concia. 1996. Penetration of vancomycin into human lung tissue. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38:865-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui, L., A. Iwamoto, J. Q. Lian, H. M. Neoh, T. Maruyama, Y. Horikawa, and K. Hiramatsu. 2006. Novel mechanism of antibiotic resistance originating in vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:428-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalla Costa, T., A. Nolting, K. Rand, and H. Derendorf. 1997. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modelling of the in vitro antiinfective effect of piperacillin-tazobactam combinations. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 35:426-433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Drusano, G. L., C. M. Rubino, P. G. Ambrose, S. M. Bhavnani, A. Forrest, A. Louie, M. Gotfried, and K. A. Rodvold. Penetration of vancomycin (V) into epithelial lining fluid (ELF). Abstr. 47th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. A-11.

- 8.Gumbo, T., A. Louie, M. R. Deziel, L. M. Parsons, M. Salfinger, and G. L. Drusano. 2004. Selection of a moxifloxacin dose that suppresses drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by use of an in vitro pharmacodynamic infection model and mathematical modeling. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1642-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hidayat, L. K., D. I. Hsu, R. Quist, K. A. Shriner, and A. Wong-Beringer. 2006. High-dose vancomycin therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: efficacy and toxicity. Arch. Intern. Med. 166:2138-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiramatsu, K., N. Aritaka, H. Hanaki, S. Kawasaki, Y. Hosoda, S. Hori, Y. Fukuchi, and I. Kobayashi. 1997. Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet 350:1670-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffres, M. N., W. Isakow, J. A. Doherty, P. S. McKinnon, D. J. Ritchie, S. T. Micek, and M. H. Kollef. 2006. Predictors of mortality for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus health-care-associated pneumonia: specific evaluation of vancomycin pharmacokinetic indices. Chest 130:947-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeffres, M. N., W. Isakow, J. A. Doherty, S. T. Micek, and M. H. Kollef. 2007. A retrospective analysis of possible renal toxicity associated with vancomycin in patients with health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Clin. Ther. 29:1107-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji, G., R. Beavis, and R. P. Novick. 1997. Bacterial interference caused by autoinducing peptide variants. Science 276:2027-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones, R. N. 2006. Microbiological features of vancomycin in the 21st century: minimum inhibitory concentration creep, bactericidal/static activity, and applied breakpoints to predict clinical outcomes or detect resistant strains. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42(Suppl. 1):S13-S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jumbe, N., A. Louie, R. Leary, W. Liu, M. R. Deziel, V. H. Tam, R. Bachhawat, C. Freeman, J. B. Kahn, K. Bush, M. N. Dudley, M. H. Miller, and G. L. Drusano. 2003. Application of a mathematical model to prevent in vivo amplification of antibiotic-resistant bacterial populations during therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 112:275-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kollef, M. H. 2007. Limitations of vancomycin in the management of resistant staphylococcal infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45(Suppl. 3):S191-S195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuroda, M., H. Kuroda, T. Oshima, F. Takeuchi, H. Mori, and K. Hiramatsu. 2003. Two-component system VraSR positively modulates the regulation of cell-wall biosynthesis pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 49:807-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I. Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. K. Takahashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamer, C., V. de Beco, P. Soler, S. Calvat, J. Y. Fagon, M. C. Dombret, R. Farinotti, J. Chastre, and C. Gibert. 1993. Analysis of vancomycin entry into pulmonary lining fluid by bronchoalveolar lavage in critically ill patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:281-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaPlante, K. L., and M. J. Rybak. 2004. Impact of high-inoculum Staphylococcus aureus on the activities of nafcillin, vancomycin, linezolid, and daptomycin, alone and in combination with gentamicin, in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4665-4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Lee, D., et al. 2007. 47th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. A-37.

- 21.Levine, D. P., B. S. Fromm, and B. R. Reddy. 1991. Slow response to vancomycin or vancomycin plus rifampin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Ann. Intern. Med. 115:674-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lodise, T. P., B. Lomaestro, J. Graves, and G. L. Drusano. 2008. Larger vancomycin doses (at least four grams per day) are associated with an increased incidence of nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1330-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louie, A., C. Fregeau, W. Liu, R. Kulawy, and G. L. Drusano. 2009. Pharmacodynamics of levofloxacin in a murine pneumonia model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: determination of epithelial lining fluid (ELF) targets. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3325-3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meagher, A. K., A. Forrest, A. Dalhoff, H. Stass, and J. J. Schentag. 2004. Novel pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model for prediction of outcomes with an extended-release formulation of ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2061-2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moise-Broder, P. A., A. Forrest, M. C. Birmingham, and J. J. Schentag. 2004. Pharmacodynamics of vancomycin and other antimicrobials in patients with Staphylococcus aureus lower respiratory tract infections. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 43:925-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moise-Broder, P. A., G. Sakoulas, G. M. Eliopoulos, J. J. Schentag, A. Forrest, and R. C. Moellering, Jr. 2004. Accessory gene regulator group II polymorphism in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is predictive of failure of vancomycin therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1700-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mwangi, M. M., S. W. Wu, Y. Zhou, K. Sieradzki, H. de Lencastre, P. Richardson, D. Bruce, E. Rubin, E. Myers, E. D. Siggia, and A. Tomasz. 2007. Tracking the in vivo evolution of multidrug resistance in Staphylococcus aureus by whole-genome sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:9451-9456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rybak, M., B. Lomaestro, J. C. Rotschafer, R. Moellering, Jr., W. Craig, M. Billeter, J. R. Dalovisio, and D. P. Levine. 2009. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 66:82-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakoulas, G., G. M. Eliopoulos, R. C. Moellering, Jr., R. P. Novick, L. Venkataraman, C. Wennersten, P. C. DeGirolami, M. J. Schwaber, and H. S. Gold. 2003. Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator (agr) group II: is there a relationship to the development of intermediate-level glycopeptide resistance? J. Infect. Dis. 187:929-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakoulas, G., G. M. Eliopoulos, R. C. Moellering, Jr., C. Wennersten, L. Venkataraman, R. P. Novick, and H. S. Gold. 2002. Accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in geographically diverse Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1492-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakoulas, G., R. C. Moellering, Jr., and G. M. Eliopoulos. 2006. Adaptation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the face of vancomycin therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42(Suppl. 1):S40-S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakoulas, G., P. A. Moise-Broder, J. Schentag, A. Forrest, R. C. Moellering, Jr., and G. M. Eliopoulos. 2004. Relationship of MIC and bactericidal activity to efficacy of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2398-2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shopsin, B., A. Drlica-Wagner, B. Mathema, R. P. Adhikari, B. N. Kreiswirth, and R. P. Novick. 2008. Prevalence of agr dysfunction among colonizing Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Infect. Dis. 198:1171-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sieradzki, K., and A. Tomasz. 2006. Inhibition of the autolytic system by vancomycin causes mimicry of vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus-type resistance, cell concentration dependence of the MIC, and antibiotic tolerance in vancomycin-susceptible S. aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:527-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevens, D. L. 2006. The role of vancomycin in the treatment paradigm. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42(Suppl. 1):S51-S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tam, V. H., A. Louie, T. R. Fritsche, M. Deziel, W. Liu, D. L. Brown, L. Deshpande, R. Leary, R. N. Jones, and G. L. Drusano. 2007. Impact of drug-exposure intensity and duration of therapy on the emergence of Staphylococcus aureus resistance to a quinolone antimicrobial. J. Infect. Dis. 195:1818-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treyaprasert, W., S. Schmidt, K. H. Rand, U. Suvanakoot, and H. Derendorf. 2007. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of in vitro activity of azithromycin against four different bacterial strains. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29:263-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsuji, B. T., and M. J. Rybak. 2005. Short-course gentamicin in combination with daptomycin or vancomycin against Staphylococcus aureus in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model with simulated endocardial vegetations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2735-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuji, B. T., M. J. Rybak, K. L. Lau, and G. Sakoulas. 2007. Evaluation of accessory gene regulator (agr) group and function in the proclivity towards vancomycin intermediate resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1089-1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsuji, B. T., C. von Eiff, P. A. Kelchlin, A. Forrest, and P. F. Smith. 2008. Attenuated vancomycin bactericidal activity against Staphylococcus aureus hemB mutants expressing the small-colony-variant phenotype. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1533-1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vuong, C., H. L. Saenz, F. Gotz, and M. Otto. 2000. Impact of the agr quorum-sensing system on adherence to polystyrene in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1688-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]