Abstract

β-1,6-Glucan is a fungus-specific cell wall component that is essential for the retention of many cell wall proteins. We recently reported the discovery of a small molecule inhibitor of β-1,6-glucan biosynthesis in yeasts. In the course of our study of its derivatives, we found a unique feature in their antifungal profile. D21-6076, one of these compounds, exhibited potent in vitro and in vivo antifungal activities against Candida glabrata. Interestingly, although it only weakly reduced the growth of Candida albicans in conventional media, it significantly prolonged the survival of mice infected by the pathogen. Biochemical evaluation of D21-6076 indicated that it inhibited β-1,6-glucan synthesis of C. albicans, leading the cell wall proteins, which play a critical role in its virulence, to be released from the cell. Correspondingly, adhesion of C. albicans cells to mammalian cells and their hyphal elongation were strongly reduced by the drug treatment. The results of the experiment using an in vitro model of vaginal candidiasis showed that D21-6076 strongly inhibited the invasion process of C. albicans without a significant reduction in its growth in the medium. These evidences suggested that D21-6076 probably exhibited in vivo efficacy against C. albicans by inhibiting its invasion process.

Modern advances in treatment, especially for patients with immune deficiencies, have led to a larger population of those being susceptible to opportunistic pathogens, thereby increasing the importance of Candida species as pathogens (16, 39). In spite of the recent progress of antifungal drugs, the mortality rate for systemic candidiasis remains significantly high. Moreover, the management of candidiasis is complicated by the limited treatment options, resulting in the emergence of various problems in medical care, such as recurrence and biofilm (5, 24, 30). Drugs with a new mode of action could offer more-preferable options. In recent years, a great deal of effort has been made to identify essential and fungus-specific targets. In addition, the invasion process of candidiasis has become the focus as a potential target of novel antifungal drugs (8, 14, 17, 35).

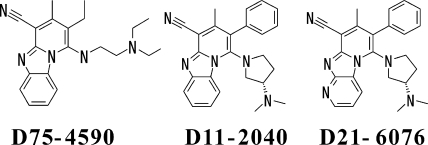

We recently discovered a specific inhibitor of β-1,6-glucan synthesis named D75-4590 (11) (A. Kitamura, K. Someya, and R. Nakajima, U.S. patent application 20040091949; international patent application PCT/JP01/03630 [2003]) (Fig. 1). Genetic studies suggested that its primary target is Kre6p, which is conserved in various fungi (Kitamura et al., U.S. patent application 20040091949; international patent application PCT/JP01/03630 [2003]). D75-4590 shows activity against most Candida species but not against Cryptococcus neoformans or Aspergillus species in a conventional in vitro antifungal test (11). Since β-1,6-glucan is thought to be an essential component for yeast and neither Kre6p nor β-1,6-glucan exists in mammalian cells, D75-4590 is expected to be a promising lead for antifungal drugs (15, 19, 25). From a different point of view, since it is the first inhibitor of β-1,6-glucan synthesis, it would be a variable tool to investigate the role of β-1,6-glucan in various fungi for their growth as well as their pathogenesis, which is the main focus of this study. One of our interests lies in our hypothesis that the β-1,6-glucan inhibitors could show in vivo efficacy not only by inhibiting the growth of fungi but also by attenuating their pathogenesis (11).

FIG. 1.

Structures of compounds.

Although D75-4590 does not have potent activity and good physicochemical properties to show significant efficacy in animal models, the chemical modifications of D75-4590 have enabled us to obtain compounds with more-preferable profiles and to investigate the various effects of β-1,6-glucan inhibitors in vitro as well as in vivo. We have started this study with two of these compounds, D11-2040 and D21-6076.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain and media.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Four pathogenic fungal strains, Candida albicans ATCC 24433, C. albicans ATCC 90028, Candida glabrata ATCC 48435, and Candida krusei ATCC 44507, were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection; the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka; or Teikyo Institute of Medical Mycology. All the strains were stored at −80°C and were cultured in YNB (0.67% yeast nitrogen base with amino acid, 2% glucose) plus requirements and 2% agar or Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA; Difco, Detroit, MI) prior to use. All the strains were grown at 30°C, unless otherwise specified. The mediums used were MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-buffered RPMI 1640 (21), YNB, minimum essential medium (MEM) (0.01 g/liter biotin [pH 7.0]; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), Sabouraud dextrose broth (SDB; Difco), hyphal forming medium 7 (HFM-7; 5 g/liter glucose, 0.26 g/liter Na2HPO4·12H2O, 0.66 g/liter KH2PO4, 0.08 g/liter MgSO4·7H2O, 0.33 g/liter NH4Cl, 16 mg/liter biotin, 4% fetal bovine serum) (10), Lee's medium (13), Spider medium (3), and RP medium (RPMI 1640 [Sigma], 2.5% fetal calf serum, 20 mM HEPES, 16 mM sodium hydrogen carbonate [pH 7.0]) (38). Requirements were added when necessary. Escherichia coli DH5α was used for the propagation of plasmids and was grown in Luria broth or agar (Difco) with 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Sigma) when appropriate.

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source/reference |

|---|---|---|

| YPH500 | matα ade2 his3 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 | 28 |

| AY-10c | Δskn1::URA3 ade2 his3 lys2 in YPH500 background | Kitamura et al., U.S. patent application 20040091949; international patent application PCT/JP01/03630 (2003) |

| CY-1aa | Δkre6::HIS3 pUAE1 (ScKRE6) in AY-10c | This study |

| CY-3aa | Δkre6::HIS3 pUAE3 (ScKRE6-CaSKN2) in AY-10c | This study |

| CY-4aa | Δkre6::HIS3 pUAE4 (ScKRE6-CaKRE6) in AY-10c | This study |

| CY-5aa | Δkre6::HIS3 pUAE5 (ScKRE6-CaSKN1) in AY-10c | This study |

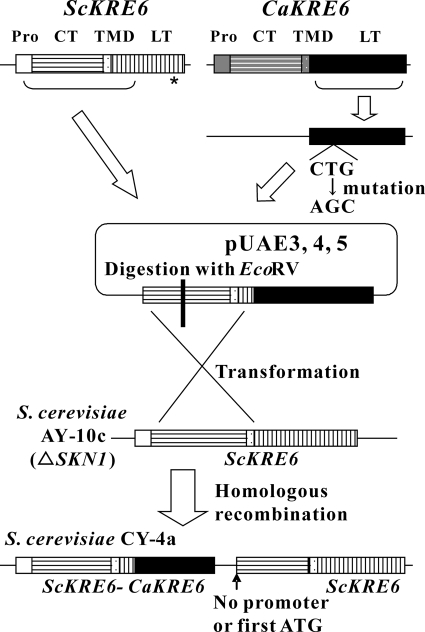

The strains were constructed by the methods illustrated in Fig. 2. CY-1a, CY-3a, CY-4a, and CY-5a are designed to express ScKre6p or the fusion protein of ScKre6p and C. albicans Skn2p, Kre6p, or Skn1p, respectively, under the promoter of ScKRE6.

Chemicals.

D75-4590 {2-ethyl-(2-N′,N′-DEAE)amino-3-methylpyrido [1,2-α]benzimidazole-4-carbonitrile}, D11-2040 {1-[(3S)-3-N′,N′-dimethylaminopyrrolidin-1-yl]-3-methyl-2-phenylpyrido[1,2-α]benzimidazole-4-carbonitrile}, D21-6076 {6-[(3S)-3-N′,N′-dimethylaminopyrrolidin-1-yl]-8-methyl-7-phenyldipyrido[1,2-α; 2′,3′-d] imidazole-9-carbonitrile} (their structures are shown in Fig. 1), and nine other derivatives were synthesized in our laboratories. The drugs were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and were used for the biological test with the final concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide at less than 1%.

Construction of CY-3a, CY-4a, and CY-5a.

SKN1 (a homologue of KRE6) of S. cerevisiae AY-10 was disrupted by replacing its open reading frame with a URA3 marker-yielding strain, AY-10c (Kitamura et al., U.S. patent application 20040091949; international patent application PCT/JP01/03630 [2003]). Strain CY-1a, which expresses S. cerevisiae KRE6 (ScKRE6) (25), and strains CY-3a, CY-4a, and CY-5a, which express the fusion gene containing the N terminus of ScKRE6 and the C terminus of each of three KRE6 homologues of C. albicans (CaKRE6, CaSKN1, and CaSKN2) (18), were constructed from strain AY-10c, as follows, using the primers listed in Table 2 (the construction strategy is shown in Fig. 2). First, we constructed a YIp-type plasmid containing a HIS3 cassette and the wild type or each of the fused KRE6 genes without the promoter region. A HIS3 cassette obtained by digesting pRS403 (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX) with SspI and PstI was inserted into the HincII and PstI site of pUC19 to generate pUXS4. ScKRE6 was amplified by PCR (template, S. cerevisiae YPH500 [29] genomic DNA; primers, SCKRE6-Sen3 and SCKRE6-Anti3) and subcloned into pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, WI) to generate pUAO1. pUAA2, which is a pUC19-based plasmid containing a part of CaKRE6, was obtained from our genomic library, made from C. albicans ATCC 24433 genomic DNA. The parts of CaSKN1 and CaSKN2, which code for the C-terminal region (predicted luminal/periplasmic domain) of each protein, were amplified by PCR (template, C. albicans ATCC 24433 genomic DNA; primers, CASKN1-Sen2 and CASKN1-Anti2 for CaSKN1; primers, CAKRE6-Sen4 and CAKRE6-Rev2) and subcloned into pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, WI) to generate pUAD9 and pUAD10, respectively. Since the CUG codon is not translated into leucine but into serine in C. albicans, the CUG codons in the cloned CaKRE6 and CaSKN1 were changed into AGC, AGT, or TTA by using a transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) so that they were translated into serine in S. cerevisiae. Specifically, mutations were induced into pUAA2 and pUAD9 using mutation primers of CAKRE6h-MP9 for pUAA2, CASKN1-MP1, and CASKN1-MP2 for pUAD9, yielding pUAD12 and pUAD11, respectively. The parts of ScKRE6, which code for the N-terminal region of ScKRE6 (predicted cytoplasmic domain) and a predicted transmembrane domain, were amplified by PCR (template, S. cerevisiae YPH500 genomic DNA; primers, SCKRE6-Sen3 and SCKRE6-Anti4), yielding pUAD5. A fragment obtained by digestion of pUAD5 with BamHI and BglII was inserted into the BamHI site of pUXS-4 to generate pUAD7. A fragment obtained by the digestion of pUAD10, pUAD9, and pUAA2 with BamHI and PvuII was inserted into the BamHI and SspI site of pUAD7 to generate pUAE3, pUAE4, and pUAE5, respectively. A fragment obtained by the digestion of pUAO1 with SphI and NheI (ScKRE6 without a promoter region) was inserted into the XbaI site of pUXS-1 to generate pUAE1. pUAE1 was digested with XbaI, and pUAE3, pUAE4, and pUAE5 were digested with EcoRV (within the region of the ScKRE6 open reading frame) and were introduced into the chromosomal DNA of S. cerevisiae AY-10c to generate S. cerevisiae CY-1a, CY-3a, CY-4a, and CY-5a, respectively. Since KRE6 genes of pUAE1, pUAE3, pUAE4, and pUAE5 do not have a promoter region, S. cerevisiae CY-1a expresses only wild-type ScKRE6, and CY-3a, CY-4a, and CY-5a express only chimeric KRE6.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Gene | Purpose | Direction | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCKRE6-Sen3 | ScKRE6 | PCR | Forward | 5′-CGCGGCCGTAACAAAACGAACAACATGAGACAAAACCCG-3′ |

| SCKRE6-Anti3 | ScKRE6 | PCR | Reverse | 5′-CGAGGCCTTTAGTTCCCTTTATGACCCGATTTGAAC-3′ |

| CASKN1-Sen2 | CaSKN1 | PCR | Forward | 5′-GCGGATCCTGATACTCCTGAAGATG-3′ |

| CASKN1-Anti2 | CaSKN1 | PCR | Reverse | 5′-GCGGCGCCTAAATATAGGGGGGTTGGTGTTTT-3′ |

| CAKRE6-Sen4 | CaSKN2 | PCR | Forward | 5′-GCGGATCCGGATACTCCACAGGACGC-3′ |

| CAKRE6-Rev2 | CaSKN2 | PCR | Reverse | 5′-CCTTCAAATATCATACAC-3′ |

| SCKRE6-Sen3 | ScKRE6 | PCR | Forward | 5′-CGCGGCCGTAACAAAACGAACAACATGAGACAAAACCCG-3′ |

| SCKRE6-Anti4 | ScKRE6 | PCR | Reverse | 5′-CGGGATCCACCAGAGATGTTCTAATGGC-3′ |

| CAKRE6h-MP9 | CaKRE6 | Mutagenesis | 5′-GGTCATTTAGAAATTAGCGCTCGTTTACCAAATTATGG | |

| CASKN1-MP1 | CaSKN1 | Mutagenesis | 5′-GGGGAAATTGGAATTTAGCGCAAAATTACCCGG-3′ | |

| CASKN1-MP2 | CaSKN1 | Mutagenesis | 5′-CCAGGGTATCTTGCCAGTACTGAAGGTGTTTGGC-3′ |

FIG. 2.

Schematic illustration for the construction of S. cerevisiae CY-4a. S. cerevisiae CY-4a, which expresses the fusion protein of ScKre6p and C. albicans Kre6p, was constructed to form S. cerevisiae AY-10c, an SKN1 null mutant, by the scheme shown here (see Materials and Methods for details of the construction). The gene encoding the C-terminal region of CaKRE6 was subcloned, and its CUG codon was changed into AGC by site-directed mutagenesis. It was fused with the gene encoding the N-terminal region of ScKRE6 without a promoter region. The resulting plasmid was digested within the region of ScKRE6 with EcoRV and was transformed into S. cerevisiae AY-10c, so that the gene encoding the C-terminal region of ScKRE6 in the host strain was replaced by CaKRE6, yielding S. cerevisiae CY-4a. S. cerevisiae CY-1a, CY-3a, and CY-5a, which express S. cerevisiae KRE6 (CY-1a) or the gene encoding the fusion protein of S. cerevisiae KRE6 and C. albicans SKN2 (CY-3a) or SKN1 (CY-5a), were constructed in similar ways. Abbreviations: Pro, promoter; CT, predicted cytoplasmic domain; TMD, predicted transmembrane domain; LT, predicted luminal/periplasmic domain.

MIC determination.

The MIC for the yeast strain was measured by the microdilution method, reported by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS), except that the incubation temperature was 30°C (21). The initial cell densities were from 1 × 103 to 3 × 104 cells/ml in all tests. The lowest MIC producing an optically clear well (MIC-0) was used as an end point for the experiments with S. cerevisiae. The lowest MIC producing a prominent reduction in turbidity (MIC-2) was used for the experiments with Candida species. To gain reproducible and precise MIC-2 values, an oxidation-reduction indicator, Alamar Blue (Biosource, Camarillo, CA), was added to MOPS-buffered RPMI medium (33). MIC-2 is defined as a 50% reduction compared with that of a drug-free control, with absorbance at 570 nm. In the test using MEM, SDB, YNB, or Spider or Lee's medium, Alamar Blue was not used, and 50% reduction was measured spectrometrically (optical density at 600 nm [OD600]). OD570/OD600 was measured with a Wallac 1420 ARVOsx (Wallac, Tokyo, Japan) multilabel counter. All experiments were performed in duplicate. When the results were not consistent, another experiment was conducted on a different day to determine the result.

In vivo study.

Five-week-old Slc:ddY female mice (Japan SLC, Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) were used. All the experiments with animals were carried out according to the guidelines provided by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Daiichi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Systemic infections with C. albicans ATCC 90028 and C. glabrata ATCC 48435 were induced in neutropenic mice. Transient immunosuppression was induced by intraperitoneal treatment with 200 mg/kg of body weight of cyclophosphamide 4 days before and 1 day after the infection. Fungal cells grown overnight in SDA were collected, and suspensions were prepared with 0.1% Tween 80 (Wako) in saline. Infections were induced by the injection of C. albicans (2.6 × 104 cells) or C. glabrata (2.4 × 108 cells) via the tail vein. The drugs were administered orally three times daily for 1 day, starting 1 hour after inoculation at a dose of 3.3 or 10 mg/kg of body weight for D21-6076. In all the experiments, each group contained 10 mice, and the control group received 0.2 ml of 5% glucose solution with 1% (vol/vol) lactic acid. The mortality of the mice was recorded for 14 or 30 days after infection.

Inhibition of β-1,6-glucan synthesis in whole cells.

The effects of D21-6076 on β-1,6-glucan synthesis were evaluated by the method described previously (11). Simply, exponentially growing cells of C. albicans ATCC 90028, C. glabrata ATCC 48435, or C. krusei ATCC 44507 were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium to give approximately 0.6 of absorbance at 595 nm. After drug solution and [14C]glucose were added, the reaction tubes were incubated at 30°C with occasional shaking. After 3 h of incubation, samples were taken, and crude fractions of (1,3)-β-glucan, chitin, mannan, and (1,6)-β-glucan were prepared as follows. The harvested cells were extracted with 3% NaOH at 80°C for 1 h. Mannan fractions were prepared from the supernatant using Fehling's reaction. Insoluble materials were washed and digested with Zymolyase 100T (Seikagaku Kougyou) overnight. After digestion, insoluble material was harvested as a chitin fraction. The supernatants were taken as glucan fractions [(1,3)-β-glucan fraction plus (1,6)-β-glucan fraction] and were dialyzed overnight. After dialysis, samples were taken as (1,6)-β-glucan fractions. The radioactivity of each fraction was counted with a toluene scintillator. The radioactivity of each β-1,3-glucan fraction was calculated by subtracting the radioactivity of the β-1,6-glucan fraction from that of the glucan fraction.

Fluorescent microscopy and TEM.

C. albicans ATCC 90028 (1 × 103 cells/ml) was treated with or without 1 μg/ml D11-2040 in MOPS-buffered RPMI for 6 h with shaking. The cells were harvested and were chemically fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde (EM Science, Tokyo, Japan)-0.1 M phosphate buffer (Kanto Chemical) for 2 h and then washed three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer. To observe its effects on the mannan layer, parts of the cells were harvested and suspended in phosphate buffer containing concanavalin A-fluorescein conjugate (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at the concentration of 10 μg/ml (34). After being stained for 30 min, the cells were washed with phosphate buffer and examined using a fluorescent microscope (Leica model DMLB100; Solms, Germany). Images were acquired using a digital charge-coupled-device camera (Olympus model DP70; Tokyo, Japan). The rest of the cells were further prepared for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The samples were postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide prepared in the same buffer for 2 h. This was followed by several washes and dehydration, and finally, the cells were embedded in Spurr's low-viscosity resin (28). Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a TEM (Hitachi H-500; Tokyo, Japan).

Adherence assay.

The adherence assay was performed fundamentally as described by Fratti et al. (7) using A549 human lung cancer cells. The human cells were grown to confluence in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C (5% CO2) in a 6-well culture plate. C. albicans cells were treated with D21-6076 in MOPS-buffered RPMI at 30°C overnight without shaking. The established monolayers of A549 cells were sequentially washed twice with 2 ml of Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), overlaid with either 100 or 200 drug-treated C. albicans cells in 1 ml of DPBS, and incubated at 37°C for 45 min in an atmosphere of air containing 5% CO2. Following incubation, monolayers of cells were washed twice with 2 ml of warm DPBS to remove nonadhering cells, and they were then covered with 2 ml of warm SDA. Yeast colonies appearing after 48 h of growth at 30°C were counted. The experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Effect on hyphal growth.

Exponentially growing cells of C. albicans ATCC 90028 were suspended in HFM-7. Cell suspensions with or without drugs were cultured on type I collagen-coated 24-well plates (Iwaki, Tokyo, Japan) to let the cells tightly adhere to the bottom of the wells. After 6 or 18 h of incubation without shaking at 37°C, cells were examined using a light microscope (Olympus model IX7). Images were acquired using a digital charge-coupled-device camera. In order to quantify the extent of hyphal growth, a crystal violet staining assay was carried out using the methods reported by Wakabayashi et al. (38), with slight modifications. Yeast-form cells of C. albicans at 1 × 104 cells/ml were cultured in RP medium with or without drugs using a 96-well flat-bottom microplate. After static incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h, the medium in the wells was gently discarded, and the adhesive Candida mycelia were sterilized by treatment with 70% ethanol, followed by washing with 0.25% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and water. The remaining mycelia were stained with 0.02% crystal violet and washed with 0.25% SDS and water. After the microplates were dried, 150 μl of isopropanol containing 0.04 N HCl and 50 μl of 0.25% SDS were added to the wells and mixed. The OD570 was measured with a Wallac 1420 ARVOsx multilabel counter. The IC50 was defined as the lowest drug concentration that results in a 50% decrease in absorbance compared with that of the drug-free control.

RHVE and model of vaginal candidiasis.

The human epithelium used for the in vitro model of vaginal candidiasis was supplied by SkinEthic Laboratories (Nice, France). It was obtained by culturing transformed human keratinocytes of cell line A431 derived from a vulval epidermoid carcinoma (26). Infection experiments were performed by the procedure described by Schaller et al. (27). Reconstituted human vaginal epithelium (RHVE) was infected with 2 × 106 cells of C. albicans ATCC 90028, and various concentrations of D21-6076 were added to the maintenance medium of the epithelial culture. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, a part of each specimen was fixed with formaldehyde. Semithin sections were studied with a light microscope equipped with a digital camera after being stained with p-aminosalicylic acid and methylene blue.

RESULTS

In vitro and in vivo activities of D21-6076.

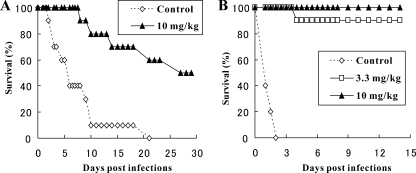

The antifungal activities of D11-2040 and D21-6076 against Candida strains were measured by the conventional NCCLS method. The results are summarized in Table 3. D11-2040 and D21-6076 showed potent activities against C. glabrata and C. krusei, which are 8 to 64 times stronger than D75-4590. The MICs of both compounds for C. glabrata are lower than those for C. krusei. Although slight growth reductions with significant morphological changes were visible at a wide range of drug concentrations, the MICs of both compounds obtained for C. albicans strains were >32 μg/ml. To comprehend the effects of the growth medium on their antifungal activity, their MICs for C. albicans in six different growth media were measured and compared. As shown in Table 4, D21-6076 and D11-2040 showed potent activity in Lee's medium and Spider medium, both of which are known to induce hyphal growth but poor activity in other media in which C. albicans cells grow mainly in yeast form. These results suggest that both compounds are likely to strongly inhibit hyphal growth but poorly inhibit budding growth. We chose D21-6076 for in vivo studies since it has more suitable physicochemical properties than D11-2040. The protective effects of D21-6076 on experimental systemic infections caused by C. glabrata ATCC 48435 as well as C. albicans ATCC 90028 were examined. D21-6076 was orally administered at 3.3 or 10 mg/kg three times a day (TID) only on the day of infection. At 0.25 h after administration of a single oral dose of 10 mg/kg, the concentration of D21-6076 in serum reached 0.71 μg/ml, and the concentration decreased, with a half-life of 4.4 h (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 3, both strains responded to therapy. With the infection caused by C. glabrata ATCC 48435, all the control mice died by day 2, and D21-6076 at a dose of 3.3 or 10 mg/kg TID gave 90 or 100% protection even on day 14. Meanwhile, with the infection caused by C. albicans ATCC 90028, a subacute lethal animal model was used since the efficacy of D21-6076 is not clear in an acute lethal model (data not shown). In that model, the control mice died by day 21 and D21-6076 at a dose of 10 mg/kg TID gave 50% protection even on day 30. The efficacy of the drug against C. albicans in the animal model was confirmed in several experiments using the same strain or a different strain with similar in vitro susceptibility to the drug. Even though the protective effect of D21-6076 against C. albicans is not as drastic as that against C. glabrata, it clearly prolonged the survival of the mice infected by C. albicans, which prompted us to investigate the effects of D21-6076 on each step of the invasion process of C. albicans and demonstrate how D21-6076 shows in vivo efficacy.

TABLE 3.

MICs of the compounds in NCCLS methodsa

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| D75-4590 | D11-2040 | D21-6076 | |

| C. albicans ATCC 24433 | 8 | >32 | >32 |

| C. albicans ATCC 90028 | 16 | >32 | >32 |

| C. glabrata ATCC 48435 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.125 |

| C. kruseiATCC 44507 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

MICs were determined using MOPS-buffered RPMI as the medium, and MIC-2 was used as the end point.

TABLE 4.

MICs of the compounds against C. albicans ATCC 24433 in various mediaa

| Medium | MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| D11-2040 | D21-6076 | |

| RPMI | >16 | >16 |

| MEM | >16 | >16 |

| SDB | 2 | 4 |

| YNB | 16 | 16 |

| Lee's | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Spider | 0.063 | 0.125 |

MIC-2 was used as the end point. Abbreviations: RPMI, MOPS-buffered RPMI; YNB, yeast nitrogen base.

FIG. 3.

Efficacies of D21-6076 in mice models. Slc:ddY mice (10 animals per group) were rendered neutropenic by intravenous administration of cyclophosphamide. They were infected intravenously with C. albicans ATCC 90028 (2.6 × 104 cells) (A) or C. glabrata ATCC 48435 (2.4 × 108 cells) (B). D21-6076 was administered orally 1, 4, and 7 h after infection.

The effects of D21-6076 and D11-2040 on the structure of the Candida cell.

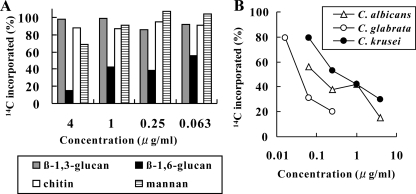

First, we evaluated the inhibitory effect of D21-6076 and D11-2040 on β-1,6-glucan synthesis. The amounts of incorporation of [14C]glucose into the cell wall fractions (β-1,3-glucan, β-1,6-glucan, chitin, and mannan) of C. albicans ATCC 90028, C. glabrata ATCC 48435, and C. krusei ATCC 44507 with or without drugs were compared by the method described in Materials and Methods. Specific reduction of the radioactivity in the β-1,6-glucan fraction by D21-6076 was observed in all the species tested in the following increasing order of activity: C. glabrata, C. albicans, and C. krusei (Fig. 4). Although its MIC for C. albicans in the medium used in this experiment was >32 μg/ml, D21-6076 significantly inhibited β-1,6-glucan synthesis even at a concentration of 0.063 μg/ml. Specific inhibitions of D11-2040 on β-1,6-glucan synthesis were confirmed in these species in the same order of activity, as well (data not shown). Next, the cell wall defects caused by the inhibition of β-1,6-glucan synthesis due to drug treatment were microscopically examined. C. albicans cells growing in a budding form were treated with D11-2040 for a longer amount of time (6 h) to clearly observe the cell wall defect and were evaluated by TEM. As expected, the cell walls of the drug-treated cells lack the darkly stained outer layer which is thought to be primarily composed of mannoproteins (Fig. 5A and B). A similar phenotype was observed in the KRE6 null mutant of S. cerevisiae as well (25). To confirm the degradation of the mannan layer, the drug-treated cells were stained with fluorescein-conjugated concanavalin A (34) and observed by fluorescent microscopy. A significant decrease in the fluorescence level was seen by drug treatment at concentrations of 0.25 μg/ml or more (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 4.

Effects of D21-6076 on β-1,6-glucan synthesis. (A) C. albicans ATCC 90028 was cultured in MOPS-buffered RPMI containing [14C]glucose with or without D21-6076. After 3 h of treatment at 30°C, cells were harvested, and β-1,3-glucan, β-1,6-glucan, chitin, and mannan fractions were prepared by the methods described in Materials and Methods. The percent changes of the incorporated radioactivities by drug treatment are displayed. (B) The percent reductions of the incorporation of [14C]glucose into β-1,6-glucan fractions in growing cells of C. albicans ATCC 90028, C. glabrata ATCC 48435, and C. krusei ATCC 44507 by the treatment of D21-6076 were compared.

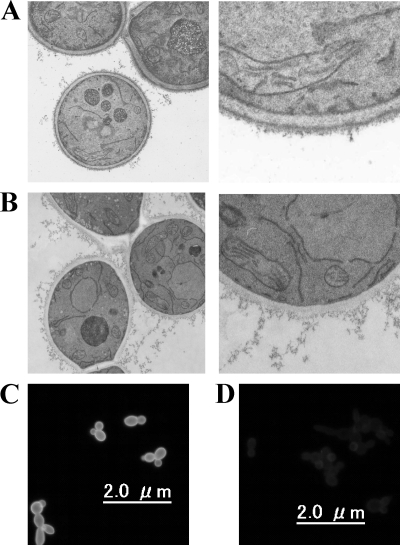

FIG. 5.

Microscopic observations of C. albicans cells treated with D21-6076. Cells were treated with D21-6076 (1 μg/ml) in MOPS-buffered RPMI medium at 30°C for 6 h. Untreated cells (A, C) and D21-6076-treated cells (B, D) were observed by transmission electron microscopy (A, B) or fluorescent microscopy after staining with fluorescein-conjugated concanavalin A (C, D).

The effects of D21-6076 on the invasion process of the Candida cell.

We next investigated the effects of D21-6076 on each process of the invasion. First, its inhibitory effects on yeast cells adherent to the monolayer of mammalian cells (A549) were measured. As shown in Fig. 6, D21-6076 strongly inhibited the adherence of all tested fungal cells to mammalian cells in the following increasing order of activity: C. glabrata, C. albicans, and C. krusei. Second, the effect of D21-6076 on the hyphal elongation of C. albicans was microscopically observed using Lee's medium (13). As shown in Fig. 7, D21-6076 clearly suppressed hyphal elongation at a concentration of 0.25 μg/ml. Similar inhibitory effects were observed when serum-containing medium (HFM-7) or Spider medium was used to induce hyphal elongation. Finally, to confirm its effect on the invasion process comprehensively, we assessed its efficacy in a vaginal candidiasis model based on RHVE. In a no-drug control well, C. albicans cells had attached to the epithelial cells and invaded into the RHVE, with hyphal formation within the first few hours after the infection. Extensive penetration of Candida cells was observed after 1 day of infection, along with vegetative growth in the medium above the RHVE. Candida cells were also detected in the medium below the RHVE as well. In contrast, in the medium with D21-6076, few Candida cells were attached to the mammalian cells, and no invasion was observed (Fig. 8). Although the fungal cells grew well in the medium above the RHVE, no cells were detected in the medium below the RHVE. These results suggested that D21-6076 had the potential to inhibit the invasion process of C. albicans cells into mammalian tissue. Similar results were observed in another experiment using reconstituted tissue consisting of KMST-6 and Caco-2 cells (data not shown).

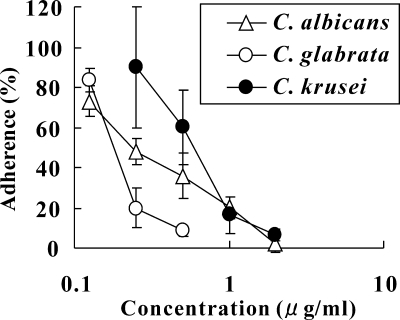

FIG. 6.

Effects of D21-6076 on adherence of the three Candida strains. Percent reductions of the adherence of C. albicans ATCC 90028, C. glabrata ATCC 48435, and C. krusei ATCC 44507 to the monolayer of mammalian cells (A549) by the treatment of D21-6076 were measured by the methods described in Materials and Methods. Data plotted are the means ± standard deviations.

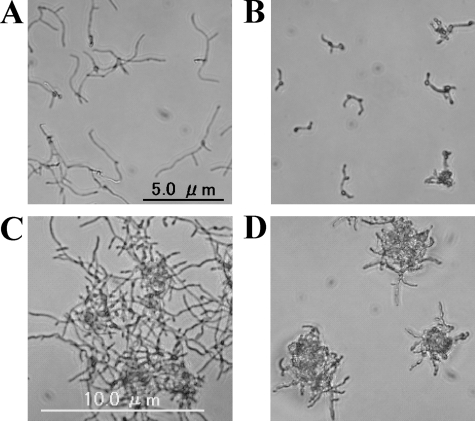

FIG. 7.

Inhibitory effect of D21-6076 on hyphal elongation of C. albicans. C. albicans ATCC 90028 cells were incubated in Lee's medium, which is known to induce hyphal elongation, with (B, D) or without (A, C) 0.25 μg/ml of D21-6076. They were microscopically observed after 6 (A, B) and 24 (C, D) hours of static incubation at 37°C.

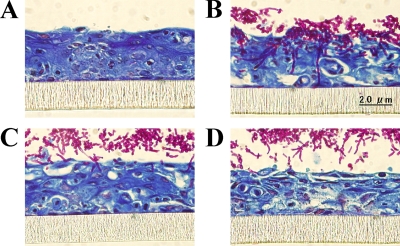

FIG. 8.

Effects of D21-6076 on the invasion process of C. albicans. The effect of D21-6076 was examined using three-dimensional epithelial tissue (A431). C. albicans ATCC 90028 cells pretreated with various concentrations of D21-6076 were added to tissue maintained in the medium with or without drugs. (A) Without fungal cells; (B) with 0 μg/ml of D21-6076; (C) with 0.25 μg/ml of D21-6076; (D) with 1 μg/ml of D21-6076.

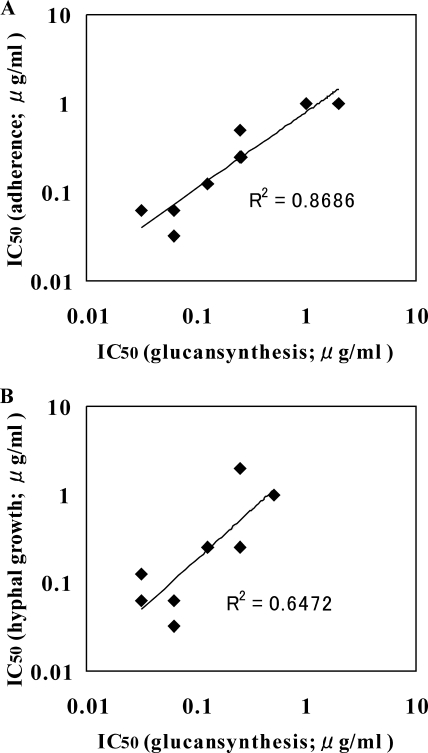

The relationship between inhibition of β-1,6-glucan synthesis, adherence, and hyphal elongation.

In theory, β-1,6-glucan inhibitors promote the release of the cell wall proteins, leading to a defect of C. albicans cells in adhesion and hyphal formation. If this is the case, positive correlations should be observed among the activities of inhibitors against these events. To confirm this, the activities of eight derivatives of D21-6076 on each event were compared. The inhibitory activities on hyphal elongation were quantified by a crystal violet staining assay (38). As shown in Fig. 9, good correlations were observed between the inhibitory effects on the β-1,6-glucan synthesis and adherence as well as that on the β-1,6-glucan synthesis and hyphal elongation. In addition, the strength order of the activity of D21-6076 against C. glabrata, C. albicans, and C. krusei is consistent in β-1,6-glucan inhibition and adherent tests, which also supports the contention that the inhibition of β-1,6-glucan contributes to the loss of the adherent nature of fungal cells.

FIG. 9.

Correlation among the activities for β-1,6-glucan synthesis, adherence, and hyphal elongation of C. albicans. (A) The correlation among the IC50s of eight derivatives of D21-6076 for β-1,6-glucan synthesis and adherence is presented. Correlation coefficient (R2), 0.87. (B) The correlation among the IC50s of eight derivatives of D21-6076 for β-1,6-glucan synthesis and hyphal elongation is presented. Correlation coefficient, 0.65.

Inhibitory effects of D21-6076 on each KRE6 homologue of C. albicans.

One of the questions that remains unsolved is why D21-6076 does not inhibit the budding growth of C. albicans in spite of its potent inhibitory activities on β-1,6-glucan synthesis. Mio et al. isolated two homologues of ScKRE6 in C. albicans, namely, CaKRE6 and CaSKN1, and their involvement in β-1,6-glucan synthesis (18). We have also isolated two homologues of ScKRE6 in C. albicans, one of which is CaKRE6, but the other was found to be different from CaSKN1. Since Northern blotting revealed that the mRNA of the novel KRE6 homologue was detectable but was much lower than that of CaKRE6 (data not shown), we tentatively named it CaSKN2 (the nucleotide sequence is available in NCBI under accession number XM_714950). The existence of three homologues in the genome of five strains of C. albicans was confirmed by PCR amplification using a specific primer for each homologue. Although Mio et al. expected that CaKRE6 would be an essential gene because they never achieved a homozygous CaKRE6 null mutation, the essentialities of these homologues were not clearly demonstrated (18). Considering the available information above, the poor activity of D21-6076 against budding growths can be explained by the hypotheses that D21-6076 does not inhibit all of the Kre6p homologues of C. albicans and/or that none of three KRE6 homologues is essential for the budding growth of C. albicans. To examine this possibility, we attempted to assess the inhibitory effects of the compounds on each of the Kre6p homologues. Although Vink et al. reported a cell-free assay system for sequential β-1,6-glucan synthesis (37), no method to detect activities for each enzyme has yet been reported. Hence, we attempted to evaluate the activities of the compounds for each of the KRE6p homologues by measuring their growth inhibitory activities against the strains expressing each homologue.

S. cerevisiae carries Kre6p (ScKre6p) and its homolog, Skn1p. Although almost no growth defects were seen in the null mutant of S. cerevisiae SKN1, the deletion of both genes leads to lethality or extremely severe growth defects (25). Therefore, the inhibition of ScKre6p by the compound for the skn1Δ mutant directly results in severe growth defects. Kre6ps are predicted to be type II membrane proteins, and their luminal/periplasmic domain was suggested to be the binding site of D75-4590, since the mutation at the near-COOH terminus of ScKre6p confers resistance to the compound (11). In consideration of the information given above, we constructed S. cerevisiae which expresses only ScKre6p or fusion proteins having an NH2-terminal region of ScKre6p and COOH-terminal regions of each Kre6p homologue of C. albicans (the construction is shown in Fig. 2) and compared its susceptibility against that of the β-1,6-glucan inhibitors. Although these transformants grow significantly slower than the parent strain, the inhibitory effects of D21-6076 can easily be measured. As shown in Table 5, the MICs of D21-6076 against these mutants (CY-3a, CY-4a, CY-5a) were similar to that against the parent strain, suggesting that D21-6076 most likely inhibits all of the Kre6p homologues of C. albicans.

TABLE 5.

MICs of the compounds against S. cerevisiae expressing various KRE6 homologuesa

| Strain | KRE6 homologue expressed | MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D75-4590 | D11-2040 | D21-6076 | ||

| AY-10c | ScKRE6 | 8 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| CY-1a | ScKRE6 | 8 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| CY-3a | ScKRE6-CaSKN2 | 8 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| CY-4a | ScKRE6-CaKRE6 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| CY-5a | ScKRE6-CaSKN1 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

MICs were determined using MOPS-buffered RPMI as the medium. MIC-0 was used as the end point.

DISCUSSION

C. albicans is a polymorphic fungus capable of converting its cell shape from a budding yeast into a filamentous form. The pathogenicity of C. albicans has been attributed to several factors that enable the pathogen to damage and penetrate tissues, to escape host immune systems, and to establish systematic infections (12, 17). Three important factors for pathogenicity are adherence to mammalian cells, hyphal elongation, and protease secretion. That is, yeast cells adhere to mammalian cells and then invade tissue by switching their growth from a unicellular yeast form into pseudohyphae or hyphae, with proteases attacking the host cell membranes throughout the process (17). Genetic analyses have provided a great deal of information about the genes involved. Some of the proteins encoded by ALS and the CRH family are essential for adhesion (2, 23). Hwp1p is a hypha-specific protein which is a substrate for mammalian transglutaminases and mediates covalent attachment (22, 31). Secretory aspartic proteinase (SAP) and the phospholipase (PLD) family are involved in the invasion into tissue (1, 32). Most of the proteins which play an important role in this process are not essential for budding growth, and null mutants lacking such important proteins for the invasive process have been shown to be much less virulent in an animal model. The important fact for our study is that most of these proteins have the typical features of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, with a signal peptide, a serine- and threonine-rich region, and a potential COOH-terminal domain for glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor attachment, and are most likely to covalently link to the β-1,3-glucan-chitin network via β-1,6-glucan (6). Hence, the lack of β-1,6-glucan would result in the release of these proteins from fungal cells, making them avirulent. Indeed, it is reported that the genes involved in β-1,6-glucan synthesis, such as BIG1 and KRE5, are not essential for budding growth but are essential for the full virulence in C. albicans (9, 36).

Considering the fact given above, it is reasonable that D21-6076, which potently inhibited β-1,6-glucan synthesis, also inhibited C. albicans to adhere to the mammalian cell and to allow hyphal elongation to occur. D21-6076 prolonged the survival of mice infected by C. albicans with serum concentrations less than 1 μg/ml. The inhibitory effects of D21-6076 on its invasion processes were observed at a concentration of 1 μg/ml or less, while it only slightly affected the budding growth of C. albicans, even at a concentration of 32 μg/ml. Although there remain many issues to be addressed, it seems reasonable to think that D21-6076 showed efficacy against C. albicans in an animal model, due mainly to its inhibition of the invasion process.

Although much attention has been focused on the invasion process as a target for new antifungal agents (1, 4, 23, 31, 32), almost nothing is known about the actual potency of such drugs in vivo due to the lack of an actual drug. From this point of view, D21-6076 and its derivatives could be valuable tools. One of the concerns is that a drug without activities against budding growth may only temporally suppress the progress of infection, and removal of the drug may result in treatment failure soon afterward. It is true that treatment with D21-6076 showed 100% survival of mice infected with C. glabrata, while it gave only a partial response in those infected with C. albicans. However, this difference is reasonable considering that D21-6076 showed stronger activity against C. glabrata than C. albicans in all the in vitro evaluations, including an adherence test. The fact that 1-day treatment of D21-6076 gave 100% survival of mice infected with C. albicans even on day 8 indicated that it may act in more ways than just by inhibiting the progress of infection. Moreover, a 5-day treatment with another derivative, which has a similar in vitro antifungal profile, leads to 100% survival, even at 30 days after infection (data not shown). These data suggested that a β-1,6-glucan inhibitor by itself could treat systemic candidiasis. Still, more-comprehensive and -detailed studies are needed to further understand the effect of such a compound in vivo.

Although indirectly, our study suggested that D21-6076 inhibited all Kre6p homologues of C. albicans. Therefore, the most simple and reasonable explanation for the poor activity of D21-6076 against yeast-type C. albicans cells is that KRE6 genes are not essential for its budding growth. Several other explanations, however, are possible. One possibility is that D21-6076 inhibits the interaction of Kre6p and other proteins or indirectly inhibits Kre6p. As we previously reported, our assumption that the primary target of these derivatives is Kre6p is based on the fact that a mutation in KRE6 confers resistance to the drugs with S. cerevisiae (11). Meanwhile, Kre6ps are suggested to be phosphorylated proteins and to have interaction with other proteins, including Keg1p (20). Therefore, it is possible that D21-6076 inhibits the proteins interacting with Kre6p and that a mutation in KRE6 confers resistance because it affects the conformation of the binding site of D21-6076. Studies are under way to demonstrate the direct interaction between these compounds and Kre6p.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrecht, A., A. Felk, I. Pichova, J. R. Naglik, M. Schaller, P. Groot, D. MacCallum, F. C. Odds, W. Schäfer, F. Klis, M. Monod, and B. Hube. 2006. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteases of Candida albicans target proteins necessary for both cellular processes and host-pathogen interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 281:688-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argimón, S., J. A. Wishart, R. Leng, S. Macaskill, A. Mavor, T. Alexandris, S. Nicholls, A. W. Knight, B. Enjalbert, R. Walmsley, F. C. Odds, N. A. Gow, and A. J. Brown. 2007. Developmental regulation of an adhesin gene during cellular morphogenesis in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 6:682-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buffo, J., M. A. Herman, and D. R. Soll. 1984. A characterization of pH-regulated dimorphism in Candida albicans. Mycopathologia 85:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cormack, B. P., N. Ghori, and S. Falkow. 1999. An adhesin of the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata mediating adherence to human epithelial cells. Science 285:578-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diekema, D. J., S. A. Messer, A. B. Brueggemann, S. L. Coffman, G. V. Doern, and L. A. Herwaldt. 2002. Epidemiology of candidemia: 3-year results from the emerging infections and the epidemiology of Iowa organisms study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1298-1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dranginis, A. M., J. M. Rauceo, J. E. Coronado, and P. N. Lipke. 2007. A biochemical guide to yeast adhesins: glycoproteins for social and antisocial occasions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71:282-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fratti, R. A., M. Ghannoum, J. E. Edwards, Jr., and S. G. Filler. 1996. Gamma interferon protects endothelial cells from damage by Candida albicans by inhibiting endothelial cell phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 64:4714-4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gale, C. A., C. M. Bendel, M. MacCellan, J. M. Becker, J. Berman, and M. K. Hostetter. 1998. Linkage of adhesion, filamentous growth, and virulence in Candida albicans to a single gene, INT1. Science 279:1355-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrero, A. B., P. Magnelli, M. K. Mansour, S. M. Levitz, H. Bussey, and C. Abeijon. 2004. KRE5 gene null mutant strains of Candida albicans are avirulent and have altered cell wall composition and hypha formation properties. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1423-1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imanishi, Y., K. Yokoyama, and K. Nishimura. 2004. Inductions of germ tube and hyphal formations are controlled by mRNA synthesis inhibitor in Candida albicans. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 45:113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura, A., K. Someya, M. Hata, R. Nakajima, and M. Takemura. 2009. Discovery of a small-molecule inhibitor of β-1,6-glucan synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:670-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumamoto, C. A., and M. D. Vinces. 2005. Alternative Candida albicans lifestyles: growth on surfaces. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59:113-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee, K. L., H. R. Buckley, and C. C. Campbell. 1975. An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for the development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida albicans. Sabouraudia 13:148-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo, H. J., J. R. Köhler, B. DiDomenico, D. Loebenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G. R. Fink. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90:939-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lussier, M., A. M. Sdicu, S. Shahinian, and H. Bussey. 1998. The Candida albicans KRE9 gene is required for cell wall beta-1,6-glucan synthesis and is essential for growth on glucose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:9825-9830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin, G. S., D. M. Mannino, S. Eaton, and M. Moss. 2003. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1546-1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mavor, A. L., S. Thewes, and B. Hube. 2005. Systemic fungal infections caused by Candida species: epidemiology, infection process and virulence attributes. Curr. Drug Targets 6:863-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mio, T., T. Yamada-Okabe, T. Yabe, T. Nakajima, M. Arisawa, and H. Yamada-Okabe. 1997. Isolation of the Candida albicans homologs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae KRE6 and SKN1: expression and physiological function. J. Bacteriol. 179:2363-2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagahashi, S., M. Lussier, and H. Bussey. 1998. Isolation of Candida glabrata homologs of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae KRE9 and KNH1 genes and their involvement in cell wall beta-1,6-glucan synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 180:5020-5029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamata, K., T. Kurita, M. S. A. Bhuiyan, K. Sato, Y. Noda, and K. Yoda. 2007. KEG1/YFR042w encodes a novel Kre6-binding endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein responsible for β-1,6-glucan synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 282:34315-34324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts, 2nd ed. Approved standard documents M27-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 22.Nobile, C. J., J. E. Nett, D. R. Andes, and A. P. Mitchell. 2006. Function of Candida albicans adhesin Hwp1 in biofilm formation. Eukaryot. Cell 10:1604-1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pardini, G., P. W. De Groot, A. T. Coste, M. Karababa, F. M. Klis, C. G. de Koster, and D. Sanglard. 2006. The CRH family coding for cell wall glycosylphosphatidylinositol proteins with a predicted transglycosidase domain affects cell wall organization and virulence of Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 281:40399-40411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2007. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20:133-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roemer, T., S. Delaney, and H. Bussey. 1993. SKN1 and KRE6 define a pair of functional homologs encoding putative membrane proteins involved in beta-glucan synthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4039-4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosdy, M., B. A. Bernard, R. Schmidt, and M. Darmon. 1986. Incomplete epidermal differentiation of A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. 22:295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaller, M., H. C. Korting, C. Borelli, G. Hamm, and B. Hube. 2005. Candida albicans-secreted aspartic proteinases modify the epithelial cytokine response in an in vitro model of vaginal candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 73:2758-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shida, H., and R. Ohga. 1990. Effect of resin use in the post-embedding procedure on immunoelectron microscopy of membranous antigens, with special reference to sensitivity. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 38:1687-1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobel, J. D., H. C. Wiesenfeld, M. Martens, P. Danna, T. M. Hooton, A. Rompalo, M. Sperling, C. Livengood III, B. Horowitz, J. Von Thron, L. Edwards, H. Panzer, and T. C. Chu. 2004. Maintenance fluconazole therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:876-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staab, J. F., S. D. Bradway, P. L. Fidel, and P. Sundstrom. 1999. Adhesive and mammalian transglutaminase substrate properties of Candida albicans Hwp1. Science 283:1535-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theiss, S., G. Ishdorj, A. Brenot, M. Kretschmar, C. Y. Lan, T. Nichterlein, J. Hacker, S. Nigam, N. Agabian, and G. A. Köhler. 2006. Inactivation of the phospholipase B gene PLB5 in wild-type Candida albicans reduces cell-associated phospholipase A2 activity and attenuates virulence. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296:405-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiballi, R. N., X. He, L. T. Zarins, S. G. Revankar, and C. A. Kauffman. 1995. Use of a colorimetric system for yeast susceptibility testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:915-917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tkacz, J. S., E. B. Cybulska, and J. O. Lampen. 1971. Specific staining of wall mannan in yeast cells with fluorescein-conjugated concanavalin A. J. Bacteriol. 105:1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toenjes, K. A., S. M. Munsee, A. S. Ibrahim, R. Jeffrey, J. E. Edwards, Jr., and D. I. Johnson. 2005. Small-molecule inhibitors of the budded-to-hyphal-form transition in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:963-972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Umeyama, T., A. Kaneko, H. Watanabe, A. Hirai, Y. Uehara, M. Niimi, and M. Azuma. 2006. Deletion of the CaBIG1 gene reduces beta-1,6-glucan synthesis, filamentation, adhesion, and virulence in Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 74:2373-2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vink, E., R. J. Rodriguez-Suarez, M. Gérard-Vincent, J. C. Ribas, H. de Nobel, H. van den Ende, A. Durán, F. M. Klis, and H. Bussey. 2004. An in vitro assay for (1→6)-beta-D-glucan synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 21:1121-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakabayashi, H., S. Abe, S. Teraguchi, H. Hayasawa, and H. Yamaguchi. 1998. Inhibition of hyphal growth of azole-resistant strains of Candida albicans by triazole antifungal agents in the presence of lactoferrin-related compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1587-1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaoutis, T. E., J. Argon, J. Chu, J. A. Berlin, T. J. Walsh, and C. Feudtner. 2005. The epidemiology and attributable outcomes of candidemia in adults and children hospitalized in the United States: a propensity analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:1232-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]