Abstract

Nosocomial outbreaks attributable to glutaraldehyde-resistant, rapidly growing mycobacteria are increasing. Here, evidence is provided that defects in porin expression dramatically increase the resistance of Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium chelonae to glutaraldehyde and another aldehyde disinfectant, ortho-phthalaldehyde. Since defects in porin activity also dramatically increased the resistance of M. chelonae to drugs, there is thus some concern that the widespread use of glutaraldehyde and ortho-phthalaldehyde in clinical settings may select for drug-resistant bacteria.

Rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM) are ubiquitous in hospitals' water sources and cause outbreaks in health care settings throughout the world (7, 22, 23, 31). Among the effective options for the disinfection of semicritical, temperature-sensitive medical devices, glutaraldehyde (GTA) remains the most widely used chemical disinfectant in hospitals worldwide due to its effective mycobactericidal activity and relatively low cost (Fig. 1). Recent reports suggest, however, that RGM are being isolated with increasing frequency from washer disinfectors and GTA-processed endoscopes, with recent Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium massiliense outbreaks being associated with the development of resistance to GTA (4, 8, 10, 17, 30).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of monomeric GTA and OPA.

GTA is thought to be predominantly a surface-reactive biocide which forms bridges or cross-links with amino groups of proteins exposed at the surface of bacterial cells (17). Although the mechanisms of resistance of mycobacteria to the disinfectant are not known, it is thus reasonable to assume that changes in the cell surface resulting in decreased binding and/or penetration of GTA may be mechanisms through which RGM develop resistance. Because of the significant role played by the mycobacterial outer membrane in drug susceptibility (3, 12) and host-pathogen interactions (5), there is thus some concern that the widespread use of GTA in clinical settings selects for resistant populations of bacteria, with possible consequences on antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity.

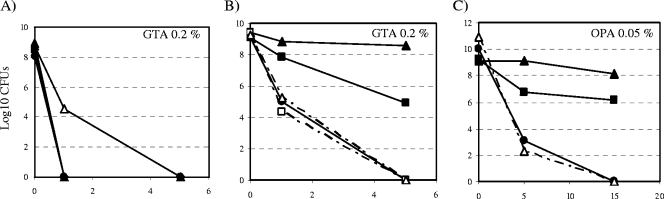

Amino group-containing compounds susceptible to binding GTA at the surface of RGM include surface-exposed proteins—among which are porins—and glycopeptidolipids. In addition, cell wall (lipo)polysaccharides have been proposed to affect the susceptibility of M. chelonae to GTA (15). To assess the impact of these cell envelope compounds on the resistance of Mycobacterium smegmatis to GTA, mc2155 isogenic mutants deficient in different aspects of their biosynthesis (Table 1) were compared to their respective wild-type (WT) parent for GTA resistance, using the suspension test described by Griffiths et al. (10). Mutants deficient in other factors known to significantly affect the susceptibility of M. smegmatis to biocides, such as phosphatidylinositol mannosides, the Lsr2 protein, and mycothiols, were also included in this study. The mutants fell into roughly three categories: (i) those whose susceptibility to GTA was not significantly altered (mc2155ΔMSMEG4250, mc2155ΔpimE, mc2155Δlsr2, Myc55, A1) (data not shown), (ii) those showing a slight increase in susceptibility (mc2155ΔMS-MEG4245, mc2155ΔembA, mc2155ΔembB) (Fig. 2A), and (iii) those displaying a significantly increased resistance to the disinfectant. The last category clearly included the mspA and mspA-mspC porin mutants, MN01 and ML10 (Fig. 2B). MspA is the main porin, constituting more than 70% of all pores of M. smegmatis (27). The ML10 mutant has at least 15- and 5-fold less porins than WT M. smegmatis and MN01, respectively (28). Complementation of MN01 and ML10 with plasmid pMN013 carrying a WT copy of the mspA gene restored the sensitivity of both mutants to GTA (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, ML10 and MN01 were also the only mutants to be significantly more resistant to ortho-phthalaldehyde (OPA) (Fig. 1 and 2C), implying the existence of at least one common mechanism of resistance to both aldehyde disinfectants.

TABLE 1.

Isogenic insertional mutants of M. smegmatis with known defects in cell envelope composition and/or biocide susceptibility

| Strain | Mutation | Description/phenotypea | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| mc2155ΔpimE | pimE | KO mutant deficient in polar PIM synthesis | Our work |

| mc2155ΔMSMEG4245 | MSMEG_4241 | KO mutant deficient in the production of WT LM and LAM; produces a truncated form of LM | 14 |

| mc2155ΔMSMEG4250 | MSMEG_4247 | KO mutant deficient in the production of LM; produces a truncated form of LAM lacking α-1,2 Manp branches on the mannan core | 13 |

| mc2155ΔembA | embA | KO mutant deficient in synthesis of the terminal hexa-arabinofuranoside motif of arabinogalactan; decreased cell wall-bound mycolic acid content | 9 |

| mc2155ΔembB | embB | KO mutant deficient in synthesis of the terminal hexa-arabinofuranoside motif of arabinogalactan; decreased cell wall-bound mycolic acid content | 9 |

| mc2155ΔembC | embC | KO mutant deficient in LAM synthesis | 32 |

| mc2155Δlsr2 (DL2008) | lsr2 | KO mutant deficient in the regulatory histone-like protein Lsr2 | 2 |

| MN01 | mspA | KO mutant deficient in the production of the major porin MspA | 27 |

| ML10 | mspA-mspC | KO mutant deficient in the production of the MspA and MspC porins | 28 |

| Myc55 | MSMEG_0408 | Transposon mutant deficient in glycopeptidolipid biosynthesis | 26 |

| A1 | mshA | Transposon mutant deficient in mycothiol biosynthesis | 19 |

KO, knockout; PIM, phosphatidylinositol mannosides; LM, lipomannan; LAM, lipoarabinomannan.

FIG. 2.

GTA and OPA susceptibility of defined isogenic mutants of M. smegmatis mc2155. Results are expressed as CFU counts upon exposure of the test organisms to the indicated concentrations of disinfectants for 0 to 15 min. (A) mc2155ΔembA (closed circles), mc2155ΔembB (closed triangles), and mc2155ΔMSMEG4245 (closed diamonds) mutants are slightly more sensitive to GTA than is their WT parent, mc2155 (open triangle). GTA (B) and OPA (C) sensitivity of the porin mutants MN01 (closed rectangles, solid line) and ML10 (closed triangles, solid line); the complemented porin mutants MN01/pMN013 (open rectangles, dashed line) and ML10/pMN013 (open triangles, dotted line); and their WT parent, SMR5 (closed circles, solid line).

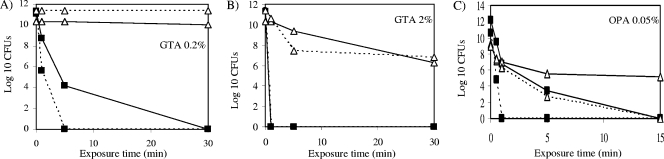

To investigate whether defects in porin production and/or surface exposure might contribute to GTA and OPA resistance in field isolates of RGM, we next analyzed a clinical isolate of M. chelonae (strain 9917) displaying high levels of resistance to both disinfectants (Fig. 3). A search for msp-like porin genes in the genome of M. chelonae ATCC 35752 identified three clustered open reading frames, MCH_4689c, MCH_4690c, and MCH_4691c, sharing about 73% identity at the amino acid level with the mature MspA protein from M. smegmatis mc2155. Sequencing of these genes in M. chelonae 9917 revealed a frameshift mutation at codon 137 of MCH_4689c, resulting in a 40-amino-acid truncation of its protein product. Unfortunately, attempts to determine porin production in strains 9917 and ATCC 35752 by immunoblot analysis using polyclonal antibodies directed against the MspA protein of M. smegmatis (20) were unsuccessful. No proteins of the expected size were detected, suggesting that the anti-MspA antibodies do not cross-react with the porins of M. chelonae or that porin expression was too low under the experimental conditions used to detect by immunoblot analysis.

FIG. 3.

Susceptibility of the M. chelonae strains ATCC 35752 and 9917 to GTA and OPA, and effect of expressing the mspA porin gene from M. smegmatis. Results are expressed as CFU counts upon exposure of the test organisms (M. chelonae ATCC 35752 [closed rectangles, solid line]; M. chelonae 9917 [open triangles, solid line]; M. chelonae ATCC 35752/pZS01 [closed rectangles, dotted line]; 9917/pZS01 [open triangles, dotted line]) to the indicated concentrations of GTA (A and B) or OPA (C) for 0 to 30 min. The increased susceptibility of 9917/pZS01 to GTA was consistently visible at the highest concentration of disinfectant (B) after 5 min of exposure, indicative of a more rapid killing of the M. chelonae recombinant isolate expressing the mspA porin gene.

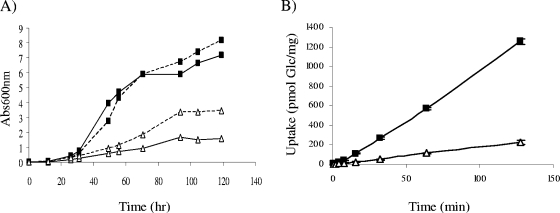

The porin-mediated influx of nutrients was shown to be a major determinant of the growth rates of M. smegmatis and Mycobacterium fortuitum (24, 28). Consistent with a defect in porin activity, strain 9917 grew significantly slower than did M. chelonae ATCC 35752 in 7H9 broth at 30°C (Fig. 4A) and was on average 5.7 ± 0.2-fold less proficient at taking up [U-14C]glucose (Fig. 4B). As expected, expression of the M. smegmatis mspA gene from the replicative plasmid pZS01 in M. chelonae 9917 partially restored growth (Fig. 4A). Importantly, expression of mspA in both M. chelonae 9917 and ATCC 35752 also resulted in increased susceptibilities to GTA (Fig. 3A and B) and OPA (Fig. 3C), although this effect was significantly more marked with the latter disinfectant in strain 9917. These different effects of expressing mspA on the susceptibility of M. chelonae 9917 and ATCC 35752 to OPA and GTA may be accounted for by differences in composition and structure of the outer membranes of these two strains and the different modes of action of the two disinfectants (17).

FIG. 4.

Growth rates and glucose uptake by M. chelonae ATCC 35752 and 9917. (A) Growth rates in 7H9-oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase broth at 30°C. Abs600nm, absorbance at 600 nm. (B) Glucose uptake. The accumulation of [U-14C]glucose by the two strains over time was measured as described previously (27) and expressed as nmol mg−1 (dry weight) cells. Uptake experiments were performed in triplicates, and the results are shown with their standard deviations. M. chelonae ATCC 35752 (closed rectangles, solid line); 9917 (open triangles, solid line); M. chelonae ATCC 35752/pZS01 (closed rectangles, dotted line); 9917/pZS01 (open triangles, dotted line).

Compared to the reference strain, M. chelonae ATCC 35752, strain 9917 displayed dramatically increased (4- to >100-fold) resistance to rifampin (rifampicin), vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, linezolid, and tetracycline (Table 2). Strongly supporting the involvement of porins in the resistance phenotypes of 9917, expression of the mspA gene from M. smegmatis in this strain increased 5- to >500-fold its susceptibility to these drugs (Table 2). Interestingly, expression of mspA from pZS01 also increased 5- to 25-fold the susceptibility of the reference strain to erythromycin, rifampin, linezolid, and tetracycline and 2- to >20-fold the susceptibility of both M. chelonae ATCC 35752 and 9917 to ethambutol, ethionamide, and chloramphenicol (Table 2). These results, which show a much more pronounced effect of porin expression on the drug susceptibility of M. chelonae than on that of M. smegmatis (6, 29), could reflect important differences in the outer membrane organization and drug efflux mechanisms of these two rapidly growing Mycobacterium spp. (21).

TABLE 2.

MICs of various drugs against M. chelonae ATCC 35752, M. chelonae 9917, M. chelonae 9917 expressing mspA (9917/pZS01), and M. chelonae ATCC 35752 expressing mspA (ATCC/pZS01)a

| Drug | MIC (μg ml−1) against:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 35752 | ATCC/pZS01 | 9917 | 9917/pZS01 | |

| AMP | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| KAN | 50 | ND | 10 | ND |

| STR | 200 | 250 | 10-20 | 10 |

| VAN | 5 | 5-10 | >500 | 25 |

| CLA | 25-50 | 50 | >250 | 25 |

| AZI | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| HYG | >500 | ND | >500 | ND |

| ERY | 20-25 | 0.25 | 500 | 1 |

| RIF | 25 | 5 | >500 | 100 |

| EMB | >500 | 25 | >500 | 250 |

| CHL | >500 | 50 | >500 | 50 |

| TOB | 25-50 | ND | 25 | ND |

| GEN | 7.5 | 7.5 | 15 | 20 |

| INH | >400 | >400 | >400 | >400 |

| ETH | >400 | 50 | >400 | 50 |

| PZA | >500 | ND | >500 | ND |

| TET | 50 | 5-10 | >500 | 25 |

| LIN | 25 | 5 | 100 | 1 |

| CIP | 1.5 | 2.5 | 5 | 1 |

| NOR | 5 | ND | 5 | ND |

MICs were determined using the colorimetric resazurin microtiter assay in 7H9-oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase broth at 30°C (16), and results were confirmed by visually scanning for growth. All assays were performed on well-dispersed bacteria and repeated at least three times on independent culture batches. AMP, ampicillin; AZI, azithromycin; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CLA, clarithromycin; EMB, ethambutol; ERY, erythromycin; ETH, ethionamide; GEN, gentamicin; HYG, hygromycin; INH, isoniazid; KAN, kanamycin; LIN, linezolid; NOR, norfloxacin; PZA, pyrazinamide; RIF, rifampin; STR, streptomycin; TET, tetracycline; TOB, tobramycin; VAN, vancomycin; ND, not determined.

Altogether, our data thus suggest that the Msp-like porin content of M. smegmatis and M. chelonae is a major determinant of the susceptibility of both species to GTA and OPA. Given the known functional similarities shared by the outer membranes of mycobacteria and gram-negative bacteria (3, 11-12, 18, 33), it is tempting to speculate that Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative opportunistic pathogens may have or could adopt a similar strategy to resist aldehyde disinfectants.

Importantly, the results of this study support the hypothesis that GTA-resistant isolates are likely to develop cross-resistances to multiple antibiotics, including some used in the clinical treatment of RGM infections. Moreover, because porins have been shown to play important roles in the pathogenicity of a number of intracellular and extracellular pathogens (1), including M. smegmatis (25), our results also raise concerns that the selection of GTA-resistant organisms may impact their pathogenicity.

Accession numbers.

The accession numbers corresponding to the porin genes of M. chelonae ATCC 35752 are FJ981588 (MCH_4689c), FJ981589 (MCH_4690c), and FJ981590 (MCH_4691c).

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank M. Daffé (CNRS-IPBS, Toulouse, France), J.-M. Reyrat (INSERM U570, Paris, France), J. Dahl (Washington State University, Pullman, WA), Y. Av-Gay (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), and D. Chatterjee and D. Kaur (CSU, Fort Collins, CO) for providing the M. smegmatis isogenic mutants described in Table 1 and F. Ripoll for sequence deposition.

This work received partial support from STERIS Corporation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achouak, W., T. Heulin, and J.-M. Pagès. 2001. Multiple facets of bacterial porins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 199:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arora, K., D. C. Whiteford, D. Lau-Bonilla, C. M. Davitt, and J. L. Dahl. 2008. Inactivation of lsr2 results in a hypermotile phenotype in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 190:4291-4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan, P. J., and H. Nikaido. 1995. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:29-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chroneou, A., S. K. Zimmerman, S. Cook, S. Willey, J. Eyre-Kelly, N. Zias, D. S. Shapiro, J. F. Beamis, and D. E. Craven. 2008. Molecular typing of Mycobacterium chelonae isolates from a pseudo-outbreak involving an automated bronchoscope washer. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 29:1088-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daffé, M., and P. Draper. 1998. The envelope layers of mycobacteria with reference to their pathogenicity. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 39:131-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danilchanka, O., M. Pavlenok, and M. Niederweis. 2008. Role of porins for uptake of antibiotics by Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3127-3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Groote, M. A., and G. Huitt. 2006. Infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:1756-1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duarte, R. S., M. C. S. Lourenco, L. S. de Souza Fonseca, S. C. Leao, E. de Lourdes, T. Amorim, I. L. L. Rocha, F. S. Coelho, C. Viana-Niero, K. M. Gomes, M. G. da Silva, N. S. de Oliveira Lorena, M. B. Pitombo, R. M. C. Ferreira, M. H. de Oliveira Garcia, G. Pinto de Oliveira, O. Lupi, B. R. Vilaca, L. R. Serradas, A. Chebabo, E. A. Marques, L. M. Teixeira, M. Dalcolmo, S. G. Senna, and J. L. M. Sampaio. 2009. An epidemic of postsurgical infections caused by Mycobacterium massiliense. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2149-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Escuyer, V. E., M.-A. Lety, J. B. Torrelles, K.-H. Khoo, J.-B. Tang, C. D. Rithner, C. Frehel, M. R. McNeil, P. J. Brennan, and C. Chatterjee. 2001. The role of the embA and embB gene products in the biosynthesis of the terminal hexaarabinofuranosyl motif of Mycobacterium smegmatis arabinogalactan. J. Biol. Chem. 276:48854-48862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffiths, P. A., J. R. Babb, C. R. Bradley, and A. P. Fraise. 1997. Glutaraldehyde-resistant Mycobacterium chelonae from endoscope washer disinfectors. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 82:519-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann, C., A. Leis, M. Niederweis, J. M. Plitzko, and H. Engelhardt. 2008. Disclosure of the mycobacterial outer membrane: cryo-electron tomography and vitreous sections reveal the lipid bilayer structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:3963-3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarlier, V., and H. Nikaido. 1994. Mycobacterial cell wall: structure and role in natural resistance to antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 123:11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaur, D., S. Berg, P. Dinadayala, B. Gicquel, D. Chatterjee, M. R. McNeil, V. Vissa, D. C. Crick, M. Jackson, and P. J. Brennan. 2006. Biosynthesis of mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan: role of a branching mannosyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:13664-13669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaur, D., M. R. McNeil, K.-H. Khoo, D. Chatterjee, D. C. Crick, M. Jackson, and P. J. Brennan. 2007. New insights into the biosynthesis of mycobacterial lipomannan arising from deletion of a conserved gene. J. Biol. Chem. 282:27133-27140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manzoor, S. E., P. A. Lambert, P. A. Griffiths, M. J. Gill, and A. P. Fraise. 1999. Reduced glutaraldehyde susceptibility in Mycobacterium chelonae associated with altered cell wall polysaccharides. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:759-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin, A., M. Camacho, F. Portaels, and J.-C. Palomino. 2003. Resazurin microtiter assay plate testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis susceptibilities to second-line drugs: rapid, simple, and inexpensive method. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3616-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonnell, G., and D. Russell. 1999. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:147-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minnikin, D. E. 1982. Lipids: complex lipids, their chemistry, biosynthesis and roles, p. 95-184. In C. Ratledge and J. Stanford (ed.), The biology of mycobacteria, vol. 1. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newton, G. L., T. Koledin, B. Gorovitz, M. Rawat, R. C. Fahey, and Y. Av-Gay. 2003. The glycosyltransferase gene encoding the enzyme catalyzing the first step of mycothiol biosynthesis (mshA). J. Bacteriol. 185:3476-3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niederweis, M., S. Ehrt, C. Heinz, U. Klocker, S. Karosi, K. M. Swiderek, L. W. Riley, and R. Benz. 1999. Cloning of the mspA gene encoding a porin from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 33:933-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikaido, H. 2001. Preventing drug access to targets: cell surface permeability barriers and active efflux in bacteria. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrini, B. 2006. Mycobacterium abscessus: an emerging rapid-growing potential pathogen. APMIS 114:319-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips, M. S., and C. Fordham von Reyn. 2001. Nosocomial infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:1363-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharbati, S., K. Schramm, S. Rempel, H. Wang, R. Andrich, V. Tykiel, R. Kunisch, and A. Lewin. 2009. Characterisation of porin genes from Mycobacterium fortuitum and their impact on growth. BMC Microbiol. 9:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharbati-Tehrani, S., J. Stephan, G. Holland, B. Appel, M. Niederweis, and A. Lewin. 2005. Porins limit the intracellular persistence of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 151:2403-2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sondén, B., D. Kocincova, C. Deshayes, D. Euphrasie, L. Rhayat, F. Laval, C. Frehel, M. Daffé, G. Etienne, and J.-M. Reyrat. 2005. Gap, a mycobacterial specific integral membrane protein, is required for glycolipid transport to the cell surface. Mol. Microbiol. 58:426-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stahl, C., S. Kubetzko, I. Kaps, S. Seeber, H. Engelhardt, and M. Niederweis. 2001. MspA provides the main hydrophilic pathway through the cell wall of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 40:451-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephan, J., J. Bender, F. Wolschendorf, C. Hoffmann, E. Roth, C. Mailaender, H. Engelhardt, and M. Niederweis. 2005. The growth rate of Mycobacterium smegmatis depends on sufficient porin-mediated influx of nutrients. Mol. Microbiol. 58:714-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephan, J., C. Mailaender, G. Etienne, M. Daffé, and M. Niederweis. 2004. Multidrug resistance of a porin deletion mutant of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4163-4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Klingeren, B., and W. Pullen. 1993. Glutaraldehyde resistant mycobacteria from bronchoscope washers. J. Hosp. Infect. 25:147-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace, R. J., Jr., B. A. Brown, and D. E. Griffith. 1998. Nosocomial outbreaks/pseudo-outbreaks caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:453-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, N., J. B. Torrelles, M. R. McNeil, V. E. Escuyer, K.-H. Khoo, P. J. Brennan, and D. Chatterjee. 2003. The Emb proteins of mycobacteria direct arabinosylation of lipoarabinomannan and arabinogalactan via an N-terminal recognition region and a C-terminal synthetic region. Mol. Microbiol. 50:69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuber, B., M. Chami, C. Houssin, J. Dubochet, G. Griffiths, and M. Daffé. 2008. Direct visualization of the outer membrane of mycobacteria and corynebacteria in their native state. J. Bacteriol. 190:5672-5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]