Abstract

Objective

To examine the benefits of adding salmeterol compared with increasing dose of inhaled corticosteroids.

Design

Systematic review of randomised, double blind clinical trials. Independent data extraction and validation with summary data from study reports and manuscripts. Fixed and random effects analyses.

Setting

EMBASE, Medline, and GlaxoWellcome internal clinical study registers.

Main outcome measures

Efficacy and exacerbations.

Results

Among 2055 trials of treatment with salmeterol, there were nine parallel group trials of ⩾12 weeks with 3685 symptomatic patients aged ⩾12 years taking inhaled steroid in primary or secondary care. Compared with response to increased steroids, in patients receiving salmeterol morning peak expiratory flow was greater at three months (difference 22.4 (95% confidence interval 15.0 to 30.0) litre/min, P<0.001) and six months (27.7 (19.0 to 36.4) litre/min, P<0.001). Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) was also increased at three months (0.10 (0.04 to 0.16) litres, P<0.001) and six months (0.08 (0.02 to 0.14) litres, P<0.01), as were mean percentage of days and nights without symptoms (three months: days—12% (9% to 15%), nights—5% (3% to 7%); six months: days—15% (12% to 18%), nights—5% (3% to 7%); all P<0.001) and mean percentage of days and nights without need for rescue treatment (three months: days—17% (14% to 20%), nights—9% (7% to 11%); six months: days—20% (17 to 23%), nights—8% (6% to 11%); all P<0.001). Fewer patients experienced any exacerbation with salmeterol (difference 2.73% (0.43% to 5.04%), P=0.02), and the proportion of patients with moderate or severe exacerbations was also lower (2.42% (0.24% to 4.60%), P=0.03).

Conclusions

Addition of salmeterol in symptomatic patients aged 12 and over on low to moderate doses of inhaled steroid gives improved lung function and increased number of days and nights without symptoms or need for rescue treatment with no increase in exacerbations of any severity.

Introduction

The 1997 British Guidelines on Asthma Management1 acknowledged the landmark study of Greening et al2 and recommended salmeterol as an alternative to increasing the dose of inhaled corticosteroids in symptomatic patients on beclometasone dipropionate (or budesonide) 100-400 μg (or fluticasone 50-200 μg) twice daily. Little guidance was given as to which choice would benefit patients most because of a lack of published data on respective outcomes. The dilemma remains today. Usually studies have measured improvement in lung function (peak expiratory flow (PEF) or forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)) as the primary variable, but a recent study looked at exacerbation rates as the primary outcome measure.3 Exacerbation data had been collected in studies that looked at the addition of salmeterol but not formally reported. We reviewed studies that compared the addition of salmeterol with an increased (at least double) dose of inhaled steroid (in patients who had symptoms on low to moderate doses of inhaled steroids) to see how rates of exacerbation were affected by the addition of salmeterol.

Methods

Searches

We searched EMBASE, Medline, and GlaxoWellcome databases before the analysis started in January 1998. All publications and abstracts from 1985 onwards in all languages were considered. In a further search in September 1999 we identified no additional studies that fulfilled the search criteria. Study search and selection was conducted by SS.

Selection

Criteria for selection of studies for inclusion in the review were randomised controlled trial; direct comparison between addition of salmeterol to current dose of inhaled steroid and increased (at least doubling) dose of current inhaled steroid for a minimum of 12 weeks; and adults or adolescents (age 12 years or over) with symptomatic asthma on current dose of inhaled steroids.

Quality assessment

All included studies were sponsored by GlaxoWellcome and all met company-wide minimum quality thresholds. All were randomised by using PACT (patient allocation for clinical trials), an in-house, computer based randomisation package validated by the Food and Drug Administration. In all studies, maintenance of the treatment blind was carefully managed with adherence to in-house standard operating procedures. In all studies, treatment packs were supplied numbered in non-identifiable packaging and were dispensed by investigators to the next sequential patient to be randomised in the trial. All studies were conducted according to good clinical practice, and all had received ethical approval. In all studies, appropriate statistical methods were used for summarising and comparing treatments, and methods for handling missing data were preplanned.

Data abstraction

Data abstraction was based on reported summary statistics (means, SD and SE, proportions) for the intention to treat population. Two independent coworkers extracted data from study reports and manuscripts, and their results were compared. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Severity of exacerbation was not reported in all studies, and so individual patient datasets were sought and obtained in all but two studies. Severity of exacerbation was assessed independently by two coworkers, without knowledge of treatment allocation or results, who applied the following criteria: severe—requiring oral steroids or admission to hospital; moderate—requiring an increase in inhaled steroid medication; mild—requiring an increase in use of rescue medication.

Quantitative data synthesis

For all measures, treatments were compared each month and for months one to six (when available), with primary interest in the comparisons at three and six months. For peak expiratory flow (recorded by patients twice daily, morning and evening, on diary cards) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) (recorded at clinic visits) the measure of effect was the difference in means. Previous experience with these measures provided assurance that they have approximately normal distributions. We used reported treatment means or medians for the week or month (as reported) immediately before the next assessment, with previous experience again suggesting approximate normality. For symptoms and use of rescue medication (recorded by the patients on their diary cards) the measure was the difference in the mean percentage of days and nights without symptoms or use of rescue medication. For these measures treatment means were obtained as the mean of the patient means (or medians, as reported), which were calculated over the interval of interest. For exacerbations (recorded in case record forms) the measure was the difference in the percentage of participants with one or more exacerbations.

The primary method of combining results was by using a fixed effect model weighting according to inverse study variance. Random effects estimators were also calculated to provide an assessment of the degree of heterogeneity.4 Evidence for statistical heterogeneity was formally tested and the potential for publication bias assessed by funnel plot.5 All analyses were conducted with SAS v6.12.

Results

Trial flow

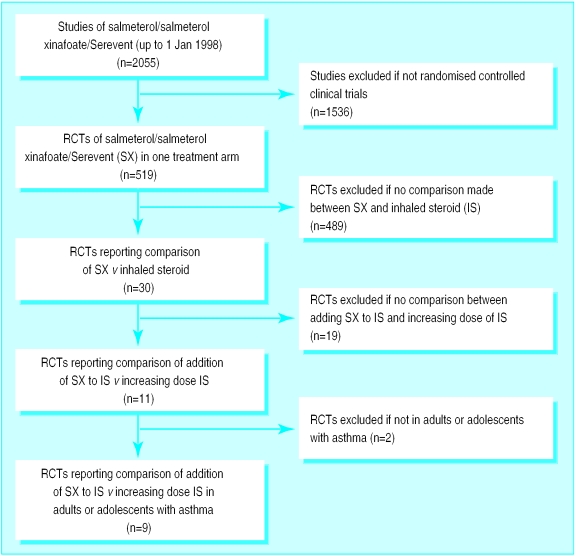

The results of the searches are presented in figure 1. The presentation follows the suggested format provided in the QUOROM statement.6 Among the nine included studies, seven have, to date, been fully published. We did not exclude any study that compared the addition of salmeterol to an increase in the dose of inhaled steroid in the management of asthma in adults.

Figure 1.

Results of search of EMBASE, Medline, and GlaxoWellcome clinical studies databases for work on salmeterol/Serevent

Study characteristics

The inclusion criteria and designs (all were parallel group) for the individual studies are given in tables 1 and 2. Treatment duration was 12 weeks in two studies and six months (24-26 weeks) in the others. To be randomised patients had to have symptoms on their current dose of inhaled steroids, defined as having symptoms (yes or no) or a minimum total (day plus night) symptom score of at least 2 on at least four of the last seven days of the run in period (symptom scale: 0 (none) to 4 (causing severe discomfort and preventing normal daily activity3). When rescue medication was required, patients must have needed to take rescue treatment four times or more within 24 hours on four of the last seven days of the run in period.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria from individual studies of asthma treatment

| Reference | Age (years) | Inhaled steroid (μg/day) | PEF/FEV1 reversibility (%) | Diurnal/period PEFR variation (%) | Absolute lung function as % predicted | Symptoms or score* | Rescue therapy use | Oral steroid use | Exacerbation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greening2 | ⩾18 | 400 | ⩾15% | ⩾15% | FEV1 ⩾50% | Yes | Not in past 6 weeks | ||

| Ind7 8 | 16-75 | 1000-1600 | PEF <90% | Score >1 on ⩾4 of past 7 days | Not if regular | ⩾2 in past 12 months, ⩾1 in past 6 months | |||

| Woolcock 9 | ⩾18 | 800-1000 | ⩾15% | ⩾15% | Yes | Yes | |||

| Kelsen10 | ⩾18 | 400 (for ⩾3 months) | ⩾12% | FEV1 45-80% | Yes | ||||

| Murray11 | ⩾18 | 400 (for ⩾3 months)† | ⩾12% | FEV1 45-80% | Yes | ||||

| Kalberg12 | ⩾12 | 400 | FEV1 40-80% | Yes | |||||

| Condemi13 | ⩾12 | 400 | FEV1 40-80% | Yes | |||||

| Van Noord14 | 18-75 | 400-600 | 10% | ⩾15% | FEV1 ⩾50% | Yes | None in past 3 months | ||

| Van Noord14 | 18-75 | 800-1200 | 10% | ⩾15% | FEV1 ⩾50% | Yes | None in past 3 months | ||

| Vermetten15 | 18-66 | 200-400 | ⩾15% | PEF >60% | None recently |

Patients were asked to record presence (yes) or absence (no) of symptoms or else to score their severity; higher scores indicate greater severity.

Or triamcinalone acetonide 800 μg/day.

Table 2.

Individual study designs for treatment of asthma

| Reference | Country | No of patients | Run in (weeks) | Duration (weeks) | Definition of ITT* | Inhaled steroid | Baseline dose (μg/day) | Comparison dose (μg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greening2 | UK | 426 | 2 | 26 | 1† | BDP | 400 | 1000 |

| Ind7 8 | Europe, Canada | 336 | 4 | 24 | 1 | Fluticasone | 500 | 1000 |

| Woolcock9 | Worldwide | 494 | 1-5 | 24 | 1 | BDP | 1000 | 2000 |

| Kelsen10 | US | 483 | 2 | 24 | 2 | BDP | 400 (336)‡ | 800 (672) |

| Murray11 | US | 514 | 2 | 24 | 2 | BDP | 400 (336)‡ | 800 (672) |

| Kalberg12 | US | 488 | 2-4 | 24 | 2 | Fluticasone | 200 (176)‡ | 500 (440) |

| Condemi13 | US | 437 | 2-4 | 24 | 2 | Fluticasone | 200 (176)‡ | 500 (440) |

| Van Noord14 | Holland | 60 | 4 | 12 | 1 | Fluticasone | 200 (LD) | 400 (LD) |

| Van Noord14 | Holland | 214 | 4 | 12 | 1 | Fluticasone | 500 (HD) | 1000 (HD) |

| Vermetten15 | Holland | 233 | 2 | 12 | 1 | BDP | 200-400 | 800 |

BDP=beclometasone dipropionate.

1—all patients randomised to treatment; 2—all patients randomised to treatment who took at least a single dose of study medication.

430 patients were randomised, but data for four patients were reported as “unverifiable” and so these patients were not included in ITT population.

UK equivalent dose (dose leaving valve), with US dose (dose leaving mouthpiece) in parentheses.

Quantitative data synthesis

Mean morning PEF and FEV1 were greater in those who received added salmeterol compared with those treated with an increased dose of inhaled steroids (table 3). At three months, morning PEF was 22.4 litre/min higher with the addition of salmeterol than with increased inhaled steroid (P<0.001), and at six months (data from only the seven studies in which treatment duration was six months) the difference was 27.7 litre/min in favour of salmeterol (P<0.001). The results for FEV1 were also in favour of salmeterol by 0.10 litre (P<0.001) and 0.08 litre (P<0.01) at three and six months respectively. There was no evidence of heterogeneity between studies for either morning PEF or FEV1.

Table 3.

Mean difference (95% confidence interval) in lung function, measured by morning peak expiratory flow (PEF) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), between treatment with salmeterol and increased dose inhaled steroids at three and six months

| No receiving added salmeterol | No receiving increased inhaled steroid | PEF (litre/min)

|

FEV1 (litre)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | ||||

| Reference | |||||||

| Greening2 | 220 | 206 | 23 (−2 to 48) | 36 (9 to 63) | 0.04 (−0.15 to 0.23) | 0.04 (−0.15 to 0.23) | |

| Ind7 8 | 171 | 165 | 19 (−5 to 44) | 18 (−7 to 43) | 0.00 (−0.20 to 0.20) | 0.00 (−0.21 to 0.21) | |

| Woolcock9 | 243 | 251 | 25 (4 to 46) | 27 (4 to 50) | 0.04 (−0.13 to 0.21) | −0.05 (−0.22 to 0.12) | |

| Kelsen10 | 239 | 244 | 30 (11 to 49) | 33 (13 to 53) | 0.21 (0.07 to 0.35) | 0.17 (0.02 to 0.32) | |

| Murray11 | 260 | 254 | 26 (8 to 44) | 29 (9 to 48) | 0.14 (0.00 to 0.28) | 0.14 (−0.01 to 0.29) | |

| Kalberg12 | 246 | 242 | 22 (−1 to 46) | 27 (2 to 51) | 0.08 (−0.06 to 0.22) | 0.05 (−0.09 to 0.19) | |

| Condemi13 | 221 | 216 | 24 (0 to 48) | 22 (−3 to 47) | 0.14 (−0.01 to 0.29) | 0.15 (0.00 to 0.30) | |

| Van Noord14 | 30 | 30 | 34 (−23 to 91) | NA | 0.18 (−0.29 to 0.65) | NA | |

| Van Noord14 | 109 | 105 | −8 (−36 to 21) | NA | −0.06 (−0.28 to 0.16) | NA | |

| Vermetten15 | 113 | 120 | 19 (−9 to 47) | NA | NM | NA | |

| Pooled results | |||||||

| Fixed effect | 22.4 (15 to 30) | 27.7 (19 to 36) | 0.10 (0.04 to 0.16) | 0.08 (0.02 to 0.14) | |||

| Random effects | 22.4 (15 to 30) | 27.7 (19 to 36) | 0.10 (0.04 to 0.16) | 0.08 (0.02 to 0.14) | |||

| Heterogeneity statistic; df (P value) | 5.508; 9 (0.79) | 1.391; 6 (0.97) | 6.971; 8 (0.54) | 5.976; 6 (0.43) | |||

NA Not applicable as duration of treatment only three months. NM Not measured or available for this study.

All studies reported the percentage of days and nights without symptoms, and all recorded the percentage of days and nights without the need for rescue treatment. The results at three and six months are shown in table 4. For all measures, at both time points, mean values were higher among patients receiving salmeterol (P<0.001). There was consistent evidence of statistical heterogeneity between studies for these measures (P<0.10 in all cases). Comparison of the confidence intervals calculated under the random effects model with those obtained under the fixed effect model, however, shows that the impact of this heterogeneity was small and almost certainly clinically unimportant. The confidence intervals calculated under the random effects model for these measures all exclude zero, with P⩽0.002 in all cases, confirming the interpretation of the fixed effects model.

Table 4.

Mean percentage (95% confidence interval) of days and nights without symptoms or use of rescue treatment at three and six months (salmeterol minus increased dose steroids)

| Days without symptoms

|

Nights without symptoms

|

Days without rescue treatment

|

Nights without rescue treatment

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 6 months | 3 months | 6 months | 3 months | 6 months | 3 months | 6 months | ||||

| Reference | |||||||||||

| Greening2 | 2 (−7 to 11) | 5 (−5 to 15) | −2 (−10 to 6) | 3 (−6 to 12) | 7 (−3 to 16) | 2 (−8 to 12) | −1 (−9 to 8) | 2 (−7 to 11) | |||

| Ind7 8 | 12 (3 to 22) | 18 (8 to 28) | 8 (0 to 16) | 11 (3 to 20) | 13 (3 to 23) | 21 (10 to 31) | 13 (4 to 22) | 16 (7 to 25) | |||

| Woolcock9 | 17 (9 to 25) | 20 (12 to 28) | 14 (7 to 21) | 14 (6 to 22) | 19 (12 to 26) | 22 (15 to 29) | 18 (12 to 24) | 15 (9 to 21) | |||

| Kelsen10 | 11 (4 to 18) | 15 (7 to 23) | 5 (0 to 9) | 4 (0 to 8) | 17 (10 to 25) | 20 (12 to 28) | 9 (3 to 14) | 7 (1 to 13) | |||

| Murray11 | 13 (7 to 20) | 19 (11 to 26) | 8 (2 to 13) | 9 (4 to 14) | 21 (14 to 27) | 24 (16 to 31) | 10 (3 to 16) | 12 (6 to 18) | |||

| Kalberg12 | 20 (13 to 27) | 18 (10 to 26) | 5 (1 to 9) | 4 (0 to 8) | 24 (16 to 31) | 22 (15 to 30) | 7 (2 to 12) | 6 (1 to 11) | |||

| Condemi13 | 10 (3 to 17) | 7 (−1 to 15) | 0 (−5 to 4) | 1 (−3 to 5) | 19 (11 to 26) | 19 (11 to 27) | 3 (−2 to 9) | 3 (−2 to 9) | |||

| Van Noord14 | 8 (−16 to 32) | NA | −5 (−30 to 20) | NA | 13 (−10 to 35) | NA | 16 (−2 to 34) | NA | |||

| Van Noord14 | 9 (−3 to 21) | NA | 5 (−6 to 17) | NA | 16 (4 to 28) | NA | 10 (−1 to 21) | NA | |||

| Vermetten15 | 1 (−10 to 12) | NA | 0 (−11 to 11) | NA | 6 (−5 to 16) | NA | 6 (−4 to 17) | NA | |||

| Pooled results | |||||||||||

| Fixed effect | 12 (9 to 15) | 15 (12 to 18) | 5 (3 to 7) | 5 (3 to 7) | 17 (14 to 20) | 20 (17 to 23) | 9 (7 to 11) | 8 (6 to 11) | |||

| Random effects | 11 (8 to 15) | 15 (11 to 19) | 5 (2 to 8) | 6 (3 to 9) | 16 (13 to 20) | 19 (14 to 24) | 9 (5 to 12) | 9 (5 to 13) | |||

| Heterogeneity statistic; df (P value) | 16.340; 9 (0.06) | 10.76; 6 (0.10) | 16.840; 9 (0.05) | 13.855; 6 (0.03) | 15.000; 9 (0.09) | 13.644; 6 (0.03) | 21.373; 9 (0.01) | 16.540; 6 (0.01) | |||

NA Not applicable as duration of study treatment only three months.

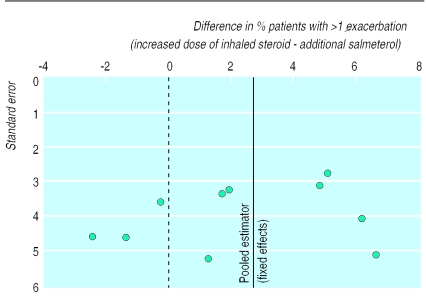

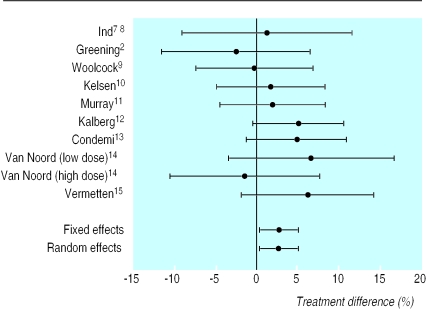

Results for exacerbations are shown in table 5. Total exacerbations (any severity) were reduced significantly (P=0.020) with added salmeterol (by 2.73%; number needed to treat=37) compared with increased dose of inhaled steroids (figs 2 and 3). Similar results were obtained for moderate or severe exacerbations only (reduced by 2.42%, P=0.029; number need to treat=41). There was no evidence of heterogeneity between studies for these measures.

Table 5.

Numbers (%) of participants with one or more exacerbations of asthma according to severity and difference (95% confidence interval) between treatment with salmeterol and increased dose of inhaled steroid

| Any (mild, moderate, or severe) exacerbation

|

Moderate or severe exacerbation

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmeterol | Inhaled steroid | Difference | Salmeterol | Inhaled steroid | Difference | ||

| Reference | |||||||

| Greening2 | 78/220 (35) | 68/206 (33) | −2.45 (−11.46 to 6.57) | 19/220 (9) | 18/206 (9) | 0.10 (−5.25 to 5.45) | |

| Ind8 | 60/171 (35) | 60/165 (36) | 1.28 (−8.97 to 11.53) | 47/171 (27) | 51/165 (31) | 3.42 (−6.30 to 13.15) | |

| Woolcock9 | 49/243 (20) | 50/251 (20) | −0.24 (−7.31 to 6.82) | 40/243 (16) | 42/251 (17) | 0.27 (−6.29 to 6.84) | |

| Kelsen10 | 37/239 (15) | 42/244 (17) | 1.73 (−4.86 to 8.33) | 18/239 (8) | 26/244 (11) | 3.12 (−1.99 to 8.24) | |

| Murray11 | 40/260 (15) | 44/254 (17) | 1.94 (−4.46 to 8.33) | 19/260 (11) | 31/254 (12) | 1.05 (−4.50 to 6.61) | |

| Kalberg12 | 20/246 (8) | 32/242 (13) | 5.09 (−0.37 to 10.56) | 15/246 (6) | 27/242 (11) | 5.06 (0.09 to 10.03) | |

| Condemi13 | 21/221 (10) | 31/216 (14) | 4.85 (−1.22 to 10.92) | 19/221 (9) | 26/216 (12) | 3.44 (−2.26 to 9.14) | |

| Van Noord14 | 0/30 | 2/30 (7) | 6.67 (−3.33 to 16.67) | NA | NA | NM | |

| Van Noord14 | 15/109 (14) | 13/105 (12) | −1.38 (−10.41 to 7.65) | NA | NA | NM | |

| Vermetten15 | 9/113 (8) | 17/120 (14) | 6.20 (−1.79 to 14.19) | NA | NA | NM | |

| Pooled results | |||||||

| Fixed effect | 2.73 (0.43 to 5.04) | 2.42 (0.24 to 4.60) | |||||

| Random effects | 2.73 (0.43 to 5.04) | 2.42 (0.24 to 4.60) | |||||

| Heterogeneity statistic; df (P value) | 5.477; 9 (0.79) | 2.687; 6 (0.85) | |||||

NA Not applicable: study treatment duration only three months. NM Not measured or available for this study.

Figure 2.

Study difference in proportion of patients with one or more exacerbations

Figure 3.

Difference in proportion of patients with one or more exacerbations (with 95% confidence intervals). Positive differences indicate treatment benefit with addition of salmeterol

Discussion

Asthma is now defined as a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways, and anti-inflammatory therapy is regarded as the cornerstone of treatment.1 Despite the use of inhaled corticosteroids to treat the inflammation, however, many patients continue to suffer from symptoms. Though the addition of salmeterol to inhaled steroids improves lung function and suppresses symptoms, previous work has not reported the effect on exacerbations, which may be regarded as a marker of underlying airway inflammation.

In this review we have shown that, compared with increased doses of steroids, additional treatment with salmeterol for symptomatic asthmatic patients on low to moderate doses of inhaled steroids leads to greater improvements in lung function and symptoms and to reduced need for rescue treatments. Moreover, we found no evidence of any increase in exacerbations, suggesting that control of airway inflammation is not compromised by this choice. For all or moderate or severe exacerbations the number needed to treat was about 40, suggesting that, compared with increasing the dose of inhaled steroid, the addition of salmeterol to the treatment of 40 patients with symptoms would prevent exacerbations in one additional patient. This updates work presented in abstract by Jenkins et al,16 who showed that in six of the studies included in this analysis in which the baseline dose of beclometasone was 400 μg/day,2,10–15 the exacerbation rates at 24 weeks were reduced more by the addition of salmeterol than by increasing the steroid dose.

The application of these results to general practice, however, reveals a potential weakness in the analysis because of the method used to select patients for the individual studies. In six of the nine included studies, a requirement for entry was a demonstrable, clinically relevant, response to β agonist (among other requirements, see table 1). In the three other studies absolute lung function measurements and the presence of symptoms were required but airway lability was not a prerequisite. This meta-analysis therefore represents a comparison among a defined population of adult or adolescent patients with asthma who were mainly responsive to β agonist and who had symptoms on their current dose of inhaled steroid. In this population those receiving an increase in inhaled steroid responded less well to this change in treatment than did those receiving the addition of the long acting bronchodilator. It might be argued, though, that this is not a surprising finding.

The individual study entry criteria, however, were chosen to reflect the evolving guidelines for the management of asthma that currently highlight the dilemma of what option to follow for stable patients who, nevertheless, still have symptoms on low to moderate doses of inhaled steroids. The analysis presented therefore examines the common decision facing physicians in daily practice as they manage patients according to the current guidelines. Patients who fail to improve with bronchodilator are commonly classified as having chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and are treated according to a different set of agreed guidelines.

The results of this meta-analysis are consistent with those obtained in the large FACET study.3 This study examined the effect of adding eformoterol (12 μg twice daily) to either low dose (200 μg/day) or high dose (800 μg/day) budesonide in the treatment of patients who were previously symptomatic but had been stabilised over four weeks on budesonide 1600 μg per day. This trial did not meet our inclusion criteria in several respects and so was not included in this meta-analysis. The similarity in findings, however, seems to suggest that the observed treatment benefits might represent a class effect rather than being specific to the drugs used in the studies included in this meta-analysis.

In conclusion, giving salmeterol to patients who have symptoms on at least 400 μg beclomethasone per day will result in better lung function, better control of symptoms, less need for rescue medication, and fewer exacerbations than increased doses of inhaled steroid. Healthcare professionals faced with the dilemma of deciding which option to follow (in the British Guidelines on Asthma Management1 at step 3) may find this review helpful when deciding on the appropriate treatment choice.

What is already known on this topic

Salmeterol improves lung function, alleviates symptoms, and reduces the use of rescue treatment when it is added to inhaled steroids in the treatment of mild to moderate asthma

Exacerbations are regarded as a marker for underlying control of the inflammation that is a key feature of asthma

What this paper adds

This meta-analysis shows that rates of exacerbation are no greater with the addition of salmeterol to moderate doses of inhaled steroids than with at least doubling the dose of steroids

This should reassure prescribers still undecided about which option to pursue at step 3 of the British Guidelines on Asthma Management

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: SS has been employed full time by GlaxoWellcome as associated medical director (respiratory) for the past four years. SP is a full time employee of GlaxoWellcome and is head of statistics. MB has been taken to international conferences, received fees for speaking, received funding for research and a respiratory nurse, and has shares in GlaxoWellcome. GlaxoWellcome manufactures Serevent (salmeterol xinafoate).

References

- 1.British Guidelines on Asthma Management. 1995 review and position statement. Thorax. 1997;52(suppl 1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greening AP, Ind PW, Northfield M, Shaw G. Added salmeterol versus higher-dose corticosteroids in asthma patients. Lancet. 1994;344:523–529. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92996-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauwels RA, Lofdahl C-G, Postma DS, Tattersfield AE, O'Byrne P, Barnes PJ, et al. Effect of inhaled formoterol and budesonide on exacerbations of asthma. New Engl J Med. 1997;337:1405–1411. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Contr Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egger M, Smith GD. Meta-analysis bias in location and selection of studies. BMJ. 1998;16:61–66. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7124.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ind PW, Dal Negro R, Colman N, Fletcher CP, Browning DC, James MH. Inhaled fluticasone propionate and salmeterol in moderate adult asthma. I. Lung function and symptoms. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1998;157:A416. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ind PW, Dal Negro R, Colman N, Fletcher CP, Browning DC, James MH. Inhaled fluticasone propionate and salmeterol in moderate adult asthma. II. Exacerbations. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1998;157:A415. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woolcock A, Lundback B, Ringdal N, Jacques LA. Comparison of addition of salmeterol to inhaled steroids with doubling of the dose of inhaled steroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1481–1488. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelsen SG, Church NL, Gillman SA, Lanier BQ, Emmett AH, Rickard KA, et al. Salmeterol added to inhaled corticosteroid therapy is superior to doubling the dose of inhaled corticosteroids: a randomized clinical trial. J Asthma. 1999;36:703–715. doi: 10.3109/02770909909055422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray JJ, Church NL, Anderson WH, Bernstein DI, Wenzel SE, Emmett A, et al. Concurrent use of salmeterol with inhaled corticosteroids is more effective than inhaled corticosteroid dose increases. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1999;20:173–180. doi: 10.2500/108854199778553028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalberg CJ, Nelson H, Yancey S, Petrocella V, Emmett AH, Rickard KA. A comparison of added salmeterol versus increased-dose fluticasone in patients symptomatic on low-dose fluticasone. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:S6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Condemi JJ, Goldstein S, Kalberg C, Yancey S, Emmett A, Rickard K. The addition of salmeterol to fluticasone propionate versus increasing the dose of fluticasone propionate in patients with persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;82:383–389. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)63288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Noord JA, Schreurs AJM, Mol SJM, Mulder PGH. Addition of salmeterol versus doubling the dose of fluticasone propionate in patients with mild to moderate asthma. Thorax. 1999;54:207–212. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermetten FAAM, Boermans AJM, Luiten WDVF, Mulder PGH, Vermue NA. Comparison of salmeterol with beclomethasone in adult patients with mild persistent asthma who are already on low-dose inhaled steroids. J Asthma. 1999;6:97–106. doi: 10.3109/02770909909065153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins C, Gordon I. A meta-analysis investigating the efficacy of adding salmeterol to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with doubling the dose of ICS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:A638. [Google Scholar]