Abstract

Values of Δ34S ( , where δ34SHS and

, where δ34SHS and  indicate the differences in the isotopic compositions of the HS− and SO42− in the eluent, respectively) for many modern marine sediments are in the range of −55 to −75‰, much greater than the −2 to −46‰ ɛ34S (kinetic isotope enrichment) values commonly observed for microbial sulfate reduction in laboratory batch culture and chemostat experiments. It has been proposed that at extremely low sulfate reduction rates under hypersulfidic conditions with a nonlimited supply of sulfate, isotopic enrichment in laboratory culture experiments should increase to the levels recorded in nature. We examined the effect of extremely low sulfate reduction rates and electron donor limitation on S isotope fractionation by culturing a thermophilic, sulfate-reducing bacterium, Desulfotomaculum putei, in a biomass-recycling culture vessel, or “retentostat.” The cell-specific rate of sulfate reduction and the specific growth rate decreased progressively from the exponential phase to the maintenance phase, yielding average maintenance coefficients of 10−16 to 10−18 mol of SO4 cell−1 h−1 toward the end of the experiments. Overall S mass and isotopic balance were conserved during the experiment. The differences in the δ34S values of the sulfate and sulfide eluting from the retentostat were significantly larger, attaining a maximum Δ34S of −20.9‰, than the −9.7‰ observed during the batch culture experiment, but differences did not attain the values observed in marine sediments.

indicate the differences in the isotopic compositions of the HS− and SO42− in the eluent, respectively) for many modern marine sediments are in the range of −55 to −75‰, much greater than the −2 to −46‰ ɛ34S (kinetic isotope enrichment) values commonly observed for microbial sulfate reduction in laboratory batch culture and chemostat experiments. It has been proposed that at extremely low sulfate reduction rates under hypersulfidic conditions with a nonlimited supply of sulfate, isotopic enrichment in laboratory culture experiments should increase to the levels recorded in nature. We examined the effect of extremely low sulfate reduction rates and electron donor limitation on S isotope fractionation by culturing a thermophilic, sulfate-reducing bacterium, Desulfotomaculum putei, in a biomass-recycling culture vessel, or “retentostat.” The cell-specific rate of sulfate reduction and the specific growth rate decreased progressively from the exponential phase to the maintenance phase, yielding average maintenance coefficients of 10−16 to 10−18 mol of SO4 cell−1 h−1 toward the end of the experiments. Overall S mass and isotopic balance were conserved during the experiment. The differences in the δ34S values of the sulfate and sulfide eluting from the retentostat were significantly larger, attaining a maximum Δ34S of −20.9‰, than the −9.7‰ observed during the batch culture experiment, but differences did not attain the values observed in marine sediments.

Dissimilatory SO42− reduction is a geologically ancient, anaerobic, energy-yielding metabolic process during which SO42−-reducing bacteria (SRB) reduce SO42− to H2S while oxidizing organic molecules or H2. SO42− reduction is a dominant pathway for organic degradation in marine sediments (23) and in terrestrial subsurface settings where sulfur-bearing minerals dominate over Fe3+-bearing minerals. For example, at depths greater than 1.5 km below land surface in the fractured sedimentary and igneous rocks of the Witwatersrand Basin of South Africa, SO42− reduction is the dominant electron-accepting process (3, 26, 46, 48, 61).

The enrichment of 32S in biogenic sulfides, with respect to the parent SO42−, imparted by SRB, is traceable through the geologic record (10, 54). The magnitude of the Δ34S (= δ34Spyrite − δ34Sbarite/gypsum, where δ34Spyrite and δ34Sbarite/gypsum are the isotopic compositions of pyrite and barite or gypsum) increases from −10‰ in the 3.47-billion-year-old North Pole deposits to −30‰ in late-Archaean deposits (55), to −75‰ in Neoproterozoic to modern sulfide-bearing marine sediments (13).

The kinetic isotopic enrichment, ɛ34S, deduced from trends in the δ34S values of SO42− and HS− in batch culture microbial SO42− reduction experiments using the Rayleigh relationship, ranges from −2‰ to −46‰ (6, 7, 11, 17, 22, 27, 28, 30, 31, 38, 39). The variation in ɛ34S values has been attributed to the SO42− concentration, the type of electron donor and its concentration, the SO42− reduction rate per cell (csSRR) (22), temperature, and species-specific isotope enrichment effects. In these laboratory experiments, doubling times are on the order of hours and csSRRs range from to 0.1 to 18 fmol cell−1 h−1 (7, 12, 17, 22, 30, 32, 39, 40).

Experiments performed during the 1960s found that the magnitude of ɛ34S was inversely proportional to the csSRR for organic electron donors (16, 31, 38, 39) when SO42− was not limiting. More-recent batch culture experiments on 3 psychrophilic (optimum growth temperature, <20°C) and mesophilic (optimum growth temperature, between 20°C and 45°C) SRB strains (7) and on 32 psychrophilic to thermophilic SRB strains (22), however, have failed to reproduce such a relationship. In 2001, Canfield (11) reported an inverse correlation between ɛ34S and reduction rate using a flowthrough sediment column and demonstrated that ɛ34S values of approximately −35 to −40‰ were produced when organic substrates added by way of amendment were limited with respect to SO42−. Because it was not possible to readily evaluate changes in biomass in the sediment column with changes in temperature or substrate provision rate, it was inferred that changes in ɛ34S were related to changes in the csSRRs. More recently, Canfield et al. (12) observed a 6‰ variation in ɛ34S values related to the temperature of the batch culture experiments relative to the optimum growth temperature. The few early experiments that were performed using H2 as the electron donor yielded ɛ34S values ranging from −3 to −19‰ (22, 38, 39), which appear to correlate with the csSRR (39). Hoek et al. (32) also found that the ɛ34S values for the thermophilic SO42− reducer Thermodesulfatator indicus increased from between −1.5‰ and −10‰ in batch cultures with high H2 concentrations to between −24‰ and −37‰ in batch cultures grown under H2 limitation with respect to SO42−. Detmers et al. (22) found that the average ɛ34S of SRB that oxidize their organic carbon electron donor completely to CO2 averaged −25‰, versus −9.5‰ for SRB that release acetate during their oxidation of their organic carbon electron donor. Detmers et al. (22) speculated that the greater free energy yield per mole of SO42− from incomplete carbon oxidation relative to that for complete carbon oxidation promotes complete SO42− reduction and hinders isotopic enrichment due to isotopic exchange of the intracellular sulfur species pools.

None of these experiments, however, have yielded ɛ34S factors capable of producing the Δ34S values of −55 to −75‰ observed in the geological record from ∼1.0 billion years ago to today. Various schemes have been hypothesized, and observations that involve either the disproportionation of S2O32− (36), the disproportionation of S0 produced by oxidation of either H2S or S2O32− (15), or the disproportionation of SO32− (29) have been made. Attribution of the increasing Δ34S values recorded for Achaean to Neoproterozoic sediments to the increasing role of H2S oxidative pathways makes sense in the context of increasing O2 concentrations in the atmosphere (14) but is not consistent with the lack of significant fractionation observed during oxidative reactions (29). To explain the Δ34S values of −55 to −77‰ reported to occur in interstitial pore waters from 100- to 300-m-deep, hypersulfidic ocean sediments (51, 64, 67), where the presence of a S-oxidative cycle is unlikely, an alternative, elaborate model of the SO42−-reducing pathway has been proposed by Brunner and Bernasconi (9). This model attributes the large Δ34S values to a multistep, reversible reduction of SO32− to HS− involving S3O62− and S2O32− (20, 25, 41, 42, 52, 66). The conditions under which the maximum ɛ34S values might be expressed are a combination of elevated HS− concentrations, electron donor limitations, nonlimiting SO42− concentrations, and a very low csSRR. The csSRR for subsurface environments has been estimated from biogeochemical-flux modeling to be 10−6 to 10−7 fmol cell−1 h−1 (23), with a corresponding cell turnover rate greater than 1,000 years (37).

Batch and chemostat culture systems, despite low growth rates, cannot completely attain a state of zero growth with constant substrate provision and therefore do not accurately reflect the in situ nutritional states of microbes in many natural settings. Retentostats, or recycling fermentor vessels, recycle 100% of biomass to the culturing vessel, allowing experimenters to culture microbial cells to a large biomass with a constant nutrient supply rate until the substrate supply rate itself becomes the growth-limiting factor and cells enter a resting state in which their specific growth rate approaches zero and they carry on maintenance metabolism (1, 47, 53, 58, 59, 62, 63). Utilizing this approach, Colwell et al. (18) were able to obtain a cell-specific respiration rate of 7 × 10−4 fmol of CH4 cell−1 h−1 for a mesophilic marine methanogen, a rate that is comparable to that estimated for methanogenic communities in deep marine sediments off the coast of Peru (49).

In this study, the conditions that Brunner and Bernasconi (9) hypothesized would lead to the large Δ34S values seen in nature were recreated in the laboratory by limiting the electron donor supply rate with respect to the SO42− supply rate in a retentostat vessel. The S isotopic enrichment by a resting culture of Desulfotomaculum putei at an extremely low csSRR was compared to that of a batch culture experiment to determine whether the ɛ34S values produced under the former conditions approach the Δ34S seen in nature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation of D. putei.

D. putei strain TH15 represents an appropriate model subsurface SRB because it is the closest culturable phylogenetic relative to the 16S rRNA clone sequences belonging to the SRB that are prevalent in South African subsurface sediments (26, 44, 46), and it was isolated from an ∼2.7-km depth in the Taylorsville Triassic Basin, VA (45). D. putei is a strictly anaerobic, SO42−- and S2O32−-reducing thermophile that grows on lactate and H2 (45). D. putei was grown in a minimal salts medium of NH4Cl (18.7 mM), MgCl2·6H2O (5 mM), CaCl2·2H2O (2.7 mM), and 0.1% Resazurin (2 ml liter−1) with N2-CO2 (70:30) headspace gas. This medium had been passed through an O2 scrubber; autoclaved; amended with sterile, anoxic solutions of NaHCO3 (10 mM final concentration), K2HPO4·3H2O (35 μM final concentration), peptones (0.2% final concentration), lactic acid (20 mM final concentration), Na2SO4 (20 mM final concentration), 10× ATCC vitamin solution (10 ml liter−1), ATCC trace mineral solution (15 ml liter−1), and Na2S to remove trace O2 (1 mM final concentration); and titrated with 3 M NaOH to a final pH of 7.8.

Batch culture cultivation.

D. putei was grown in batch culture for 72 h at 65°C and sampled for changes in biomass, aqueous geochemistry, and sulfur isotope enrichment. The lactate and SO42− concentrations were 4 and 20 mM, respectively, consistent with that of the retentostat experiments. Changes in cell concentration and morphology were determined by staining 100-μl aliquots of cells with 5 nM Sytox-13 green fluorescent dye and analyzing them using flow cytometry (FACScan; Becton-Dickinson). The cell concentration and size were calibrated to 1-μm fluorescent microspheres at known concentrations (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The uncertainty for enumeration was determined by triplicate analyses, and the 95% error of confidence was typically ±6%.

Aqueous geochemistry (SO42−, S2O32−, acetate, and lactate) samples were collected in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and were analyzed by ion chromatography-mass spectrometry (Dionex 320; Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA; Finnigan MSQ; Thermo Scientific). The detection limits were 1 μM for SO42−, acetate, and lactate and 5 μM for S2O32−. The 95% probability envelopes were ±5% for SO42−, acetate, and lactate and ±10% for S2O32−. Sulfide samples were collected in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes, and the sulfide was immediately quantified by UV spectroscopy by following the method of Cord-Ruwisch (19), which has a detection limit of 0.01 mM and a 95% probability envelope of ±5%.

Cell-specific rates of SO42− reduction (csSRRs in mol of SO4 cell−1 h−1) were calculated for the exponential phase using the changes in the SO42− levels and cell concentrations between time points 1 and 2 (T1 and T2, respectively) [SO42−(1) and SO42−(2) and X1 and X2, respectively] according to the following equation (22):

|

(1) |

The standard deviation of the csSRR was determined from duplicate measurements and was equal to ∼25%.

Retentostat cultivation.

All retentostat experiments were performed within an incubator that was housed in an anaerobic glove bag (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc., Grass Lake, MI) filled with N2-CO2 (70:30). The retentostat experiments were performed using a 1-liter culture vessel with a constant rate of fresh medium supplied at a rate of 22 ml h−1 for runs 1 and 2 and of 10 ml h−1 for run 3. The medium contained 4 mM lactate and 26 mM SO42− for run 1 and the same lactate concentration and 20 mM SO42− for runs 2 and 3. The other medium constituents were the same as described above. The vessel was inoculated with 10 ml of batch culture.

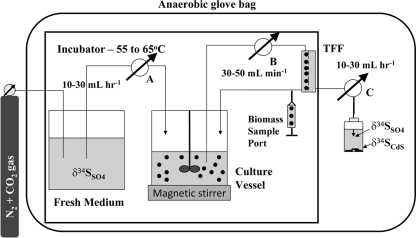

A Pellican XVG50 tangential-flow filter (Millipore Inc., CA) with a maximum pore size of 0.2 μm was used to recycle cells back into the culture vessel while allowing effluent medium to be removed at the same rate that fresh medium was being added (Fig. 1). The medium was constantly stirred with a magnetic stir bar. Samples were collected simultaneously with inoculation for time zero measurements, and the retentostat was then sampled three times every 24 h. The retentostat vessel fluid volume, which fluctuated due to slight variations in the pump rates (Fig. 1), was recorded to correct for the calculation of substrate supply rates. The maximum vessel volume fluctuation was never more than 5% of the total volume.

FIG. 1.

Retentostat experimental design. A, B, and C are peristaltic pumps where the fluid pump rate in ml h−1 for A is equal to the fluid pump rate for C. The tangential flow filter (TFF) separates biomass from effluent and delivers cells back into the culture vessel. Black dots above the stir rod represent bacterial cells. δ34SCdS represents the isotopic composition of the cadmium sulfide precipitate, and δ34SSO4 represents the isotopic composition of the sulfate.

Biomass samples were collected in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes from an in-line sampling port on the recycling biomass loop and were fixed immediately in a 2.2% glutaraldehyde solution. Cell concentration and morphology for each time point was determined by flow cytometry as described above.

Aqueous geochemistry (SO42−, S2O32−, acetate, and lactate) samples were collected in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes from the effluent port (Fig. 1) and immediately frozen at −80°C until analysis by ion chromatography-mass spectrometry, as described above. Sulfide samples were collected in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and were immediately quantified as described above. The pH of the effluent was measured at each time point using pH paper in two ranges, pHs 5 to 10 (Colorphast intermediate range; accuracy, 0.3 to 0.5; EMD Chemicals) and pHs 6.5 to 10 (Colorphast narrow range; accuracy, 0.2 to 0.3; EMD Chemicals). The dissolved inorganic carbon was measured using a LI6252 apparatus (LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). The H2 concentration in the glove bag headspace was measured by gas chromatographic analyses (Kappa5; Trace Analytical, Menlo Park, CA) on gas samples collected in serum vials before the exponential growth phase and during the maintenance metabolism phase of run 3.

The csSRR for each time point (Ti) of the experiment (csSSRi) was calculated using the following formula:

|

(2) |

where VI is the volume flow rate for the incoming fresh medium (liters h−1), VOi is the volume flow rate of the outgoing medium for sample i (liters h−1), [SO42−i] is the SO42− concentration (mol liter−1) for sample i, [SO42−(0)] is the SO42− concentration at time zero, and Xi is the cell concentration (cells liter−1) for sample i.

In order to test the effects of various csSRRs on the ɛ34S, the initial cell concentration was increased from 4.4 × 1010 cells liter−1 for run 1 to 1.5 × 1011 cells liter−1 for run 2 and to 4.7 × 1012 cells liter−1 for run 3. To determine if temperature affected the ɛ34S, the temperature of run 3 was reduced from 65 to 60°C at 640 h and then from 60 to 55°C at 692 h. The temperature was reduced from 55 to 50°C at 840 h, but the fresh medium had become contaminated at this point and the experiment was terminated.

Sulfur isotope methods.

Sulfur isotope samples were collected by adding 1 ml of 2 M CdCl2 solution to the 10 ml of medium in each tube during the course of the batch culture experiment. An uninoculated medium tube served as the negative control and was processed in the same manner to obtain the initial SO42− isotopic composition. Sulfur isotope samples were collected for the retentostat experiments by collecting 45 ml of eluent in sterile 120-ml, O2-free serum vials preloaded with 5 ml of a 2 M CdCl2 solution, capped with butyl rubber stoppers, and frozen at −20°C until processing, as previously described (8, 22). In the presence of H2S, CdS was precipitated and recovered on quartz filters, and the filters were dried in an oven overnight at 60°C. The filtrate solution was acidified to about pH 3 and heated to 80°C. Drops of a saturated BaCl2 solution were added to the filtrate until there was no visible whitening due to suspended BaSO4 crystals. The BaSO4 precipitate was washed and centrifuged three times using distilled, deionized water from a Millipore gradient Mili-Q water filtration system with a QuantumEX and Q-Gard-2 dual-filtration system.

Sulfur isotope ratios for BaSO4 and CdS were determined using an EA1110 elemental analyzer coupled to a Finnigan Mat 252 isotope ratio mass spectrometer via a ConFlo II split interface (57). Isotope data are reported as the δ34S per mille deviation from the Vienna Cañon Diablo Troilite (VCDT) calculated by using equation 3:

|

(3) |

where rsample is equal to 34Ssample/32Ssample i and rVCDT is equal to 0.0441638 (24).

Each set of 12 samples was bracketed by three working standards ranging in isotopic composition from −32.5‰ to +38.7‰ based on calibration to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) S-1 (−0.30 ‰), IAEA S-3 (−32.5‰), and NBS-127 (+20.3 ‰) external standards. Corrections were assumed to be linear over the entire range of isotopic compositions, and analytical reproducibility was better than ±0.2‰ for standards and analytical duplicates.

The ɛ34S during exponential-phase growth in batch culture was calculated using the following standard Rayleigh model for closed systems:

|

(4) |

where δ34Sproduct is the isotopic composition in the integrated HS− pool, δ34Sinit is the isotopic composition in the initial SO42− pool, and f is the fraction of SO42− remaining at a given time. The δ34Sinit was 9.97‰.

The ɛ34S during retentostat operation can be modeled as a steady-state system (50) using the following equation:

|

(5) |

where  and δ34SHS are the isotopic compositions of the SO42− and HS− in the eluent (Fig. 1).

and δ34SHS are the isotopic compositions of the SO42− and HS− in the eluent (Fig. 1).

The overall S isotope mass balance was verified by comparing the total S isotopic composition of the eluent to that of the SO42− in the fresh medium supply by using the following relationship:

|

(6) |

The δ34S value of the SO42− in the fresh medium supply was determined at the initiation of each experiment and was −0.41‰ for run 1, 0.40‰ for run 2, and 5.44‰ for run 3. These calculations also take into account the HS− present in the inoculum (∼10 mM in 10 ml) and in the 1-liter culture vessel at the beginning of each experiment (∼0.256 mM HS−) and in the 3 liters of fresh medium supply in the case of run 2. The δ34S value of the HS− in the medium supply was determined at the initiation of each experiment and was 8.74‰ for run 1, 4.94‰ for run 2, and 5.94‰ for run 3.

Geochemical modeling.

The retentostat experimental data were simulated using the React module of Geochemist's Workbench standard version 7.04 (5) by using the “flush” command and by following the dual-Monod reaction model of Jin and Bethke (34, 35):

|

(7) |

where the reaction rate, k, is in mol kg of H2O−1 s−1, Vmax is the maximum cellular rate for SO42− reduction in mol mg of biomass−1 s−1, and X is the cell concentration in mg of biomass kg of H2O−1. FA is the factor controlled by the electron-accepting reaction, FT is the thermodynamic-potential factor, and FD is the kinetic parameter controlled by the electron-donating reaction and is defined by the equation

|

(8) |

where mDPD and mD+PD+ are the concentrations of the electron donor reactant and product, respectively. Similarly, the electron-accepting reaction is controlled by the kinetic parameter FA, defined by

|

(9) |

where mAPA and mA−PA are the concentrations of the reactants of the electron-accepting reactant and product, respectively. PA and PD are assumed to be 1 for all reactions and PA− and PD+ are assumed to be 0 for all reactions. KD and KA are in molar units and are equivalent to the half-saturation constants Km and Ks. The KD value was constrained by matching the initial rate of lactate depletion. The KA value of 10−5 M reported for SRB by Ingvorsen and Jorgensen (33) was assumed, but because of the high SO42− concentrations used in these experiments, the KA had no effect on the outcome of the simulations.

FT is defined as

|

(10) |

where R is the real gas constant 8.314472 J K−1 mol−1, T is the temperature in kelvins, x is the average stoichiometric number (34) or the ratio of the free-energy change of the overall reaction to the sum of the free energy changes for each elementary step, and Γ is the net thermodynamic driving force of the reaction defined by equation 11:

|

(11) |

where ΔG is the free-energy change of the redox reaction and ΔGp is the free energy for the phosphorylation reaction ADP + P → ATP (35). ΔGp can vary from about −40 to −70 kJ mol−1, depending upon the temperature, pH, and concentrations of ADP and ATP in the cell (43), and more likely ranges from −50 to −88 kJ mol−1 if a thermodynamic efficiency of 80% is assumed. n is the number of moles of ATP generated per mole of reaction mixture. Values of four-thirds and 0.5 were utilized for n and x, respectively, according to the method of Jin and Bethke (35), but the ΔGp was constrained by matching the lactate concentration in the maintenance phase of the retentostat experiments, i.e., the threshold concentration of the lactate.

The cell concentration is given by the following relationship:

|

(12) |

where dX/dt is the change in cell concentration with time, i.e., the growth rate, Y is the yield in mg of biomass mol of reaction mixture−1, k is the reaction rate in mol of reaction mixture kg of H2O−1 s−1, and D is the death rate in s−1. Cell counts were converted to mg of biomass by assuming a cellular mass of 1.56 × 10−13 g cell−1 (30). Y and Vmax were determined by simultaneously fitting the rate of SO4−2 reduction and the cell concentrations during the growth phase. D was determined by the trend in cell concentrations during the maintenance phase. Kinetic enrichment of S isotopes was simulated by introducing 34S species into the thermodynamic database, defining a 34S microbial reaction, and then adjusting the Vmax, D, and KA for the 34S microbial reaction to fit the data.

TEM protocol.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) observations of the samples were performed subsequent to pelleting of cell suspensions and fixation with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 200 mM Na cacodylate (pH 7.2) for 2 h on ice. The pellets were then washed three times with 100 mM Na cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) and left in the buffer overnight at 4°C. The pellets were then fixed with 2% Os tetroxide in Na Veronal buffer (pH 7.2) for 1 h on ice, followed by three rinses with the Na Veronal buffer and three rinses with 50 mM Na maleate buffer (pH 5.2). The pellets were stained with 0.5% uranyl acetate in the Na maleate buffer overnight at room temperature and then rinsed three times with 50 mM Na maleate buffer. The pellets were then sequentially dehydrated with 30%, 50%, 70%, and 95% ethanol and twice with 100% ethanol, followed by immersion in propylene oxide for 30 min, a propylene oxide-resin (1:1) mixture overnight, a propylene oxide-resin (1:2) mixture for 24 h, and straight resin overnight. The pellets were then placed in Beem capsules and polymerized at 60°C overnight. Unstained 70-nm sections were obtained using a diamond knife on a Leica UC6 ultramicrotome and observed at 80 kV on a Zeiss 912AB TEM equipped with an Omega energy filter (at Princeton University) and on a Philips 420 TEM operating at 80 kV (at the University of Western Ontario). Micrographs were captured using a digital camera from Advanced Microscopy Techniques and saved as TIFF files onto a Dell personal computer (at Princeton University) and using a Hamamatsu digital camera and HP computer (at the University of Western Ontario).

Lipid analyses.

Biomass samples for membrane lipid analyses were shipped to the University of Tennessee on dry ice and stored at −80°C until analyzed. The total lipids were extracted using methanol-chloroform-buffer (2:1:0.8 [vol/vol/vol]) and subsequently fractionated on a silicic acid column with only the polar lipids then transesterified into phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) methyl esters (65). The PLFA methyl esters were separated, quantified, and identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (65).

RESULTS

Batch culture experiment.

During the batch culture experiments, 6.6 mM SO42− and 5.4 mM lactate were consumed over the 72-h period, with the production of 5.8 mM acetate. S2O32− was not detected. The csSRR for exponential-phase growth of D. putei was (0.9 ± 0.4) × 10−15 mol cell−1 h−1, with a Y of 5,180 mg mol of lactate−1, and an ɛ34S of −9.7‰ ± 0.4‰ was measured.

Retentostat experiment.

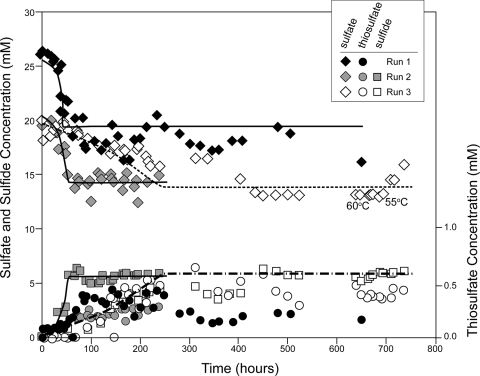

The pH and temperature remained at 7.8 ± 0.5 and 65°C, respectively, with no fluctuations throughout the duration of the experiments, except in run 3, where the temperature was purposely decreased in two steps to 55°C toward the end. During all three runs, the medium in the retentostat became progressively darker. During run 1, the SO42− concentrations decreased from 25 mM to ∼19 mM and the lactate concentrations decreased from 4.0 mM to below the detection level (Fig. 2) by the end of exponential-phase growth, when an inflection occurs in the model growth curve (Fig. 3). SO42− concentrations decreased from 20 mM to ∼14 mM and HS− concentrations increased from 0.1 mM to a maximum of 6 mM in runs 2 and 3 (Fig. 2) by the end of exponential-phase growth (Fig. 3). S2O32− concentrations increased from <6 μM to 0.3 ± 0.1 mM in a manner synchronistic with HS− production (Fig. 2). Lactate concentrations decreased from 4 mM to 4.8 ± 1.7 μM (Fig. 2) by the end of the exponential-phase growth (∼30 h in Fig. 3) of run 2 and from 4 mM to 77 ± 44 μM (Fig. 2) by the end of the exponential-phase growth (∼92 h in Fig. 3) of run 3 and remained at these low concentrations for the remainder of these experiments. Acetate increased from below 0.2 μM to 9 ± 2 mM by the end of the exponential-phase growth of run 2 and increased to 8 ± 2 mM by the end of the exponential-phase growth of run 3; it remained at these concentrations for the remainder of these experiments. No formate was detected. The HCO3− varied from 8 mM to 13 mM. The decrease in SO42− and lactate concentrations and the increase in HS− concentrations during the course of each run were consistent with the following reaction stoichiometry:

|

(13) |

The declines in SO42− concentrations for runs 1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 2) were best fitted with specific Vmax reaction rates of 8.7 × 10−10, 1.7 × 10−10, and 5.3 × 10−12 mol, respectively, of SO42− mg of biomass−1 s−1. Geochemical modeling indicated that the pH should remain at 7.8, as it is buffered by the precipitation of dolomite and the 30% CO2 in the headspace, which is consistent with the observed pH and explains the darkening of the medium. The average threshold lactate concentration was fit with a ΔGp value of −63 ± 1 kJ (mol of SO42−)−1 for run 2 and of −75 ± 1 kJ (mol of SO42−)−1 for run 3.

FIG. 2.

Concentrations of SO42−, HS−, and S2O32− versus time in retentostat runs 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Sulfide data for run 1 are not shown. Modeled reaction rates for the equation lactate + 1.5 SO42− → 1.5 HS− + 3 HCO3− + 0.5 H+ are shown for runs 1 (solid line), 2 (solid line), and 3 (sulfate, dashed line; sulfide, dashed and dotted line). ±2 S.D., 95% error in confidence error bar for SO42− (95% error in confidence error bars for HS− and S2O32− are equal to or less than the size of their symbols). 60°C and 55°C, beginnings of temperature intervals for run 3.

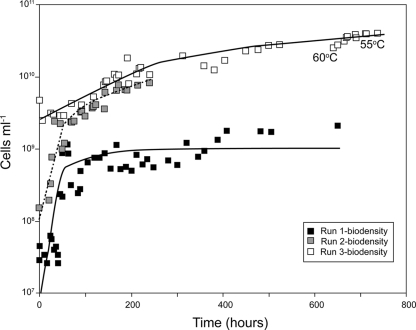

FIG. 3.

Cellular concentration versus time during retentostat runs 1, 2, and 3. Modeled growth curves shown for runs 1 (solid line), 2 (dashed line), and 3 (solid line). The 95% error in confidence error bars are smaller than the symbols. 60°C and 55°C, beginnings of temperature intervals for run 3.

As has been observed in other retentostat experiments, cell concentrations increased from the inoculum concentration through an exponential phase of growth until the substrate feed became limiting and the growth rate declined and, in the case of run 1, approached zero (Fig. 3). The geochemically modeled curves simulate the overall trend in declining growth rates (Fig. 3). A maximum cell concentration of 2 × 109 cells ml−1 was observed for run 1 by 408 h, 8 × 109 cells ml−1 was observed for run 2 by 171 h, and 3 × 1010 cells ml−1 was observed for run 3 by 450 h (Fig. 3). Run 2 may have been terminated prior to attaining maximum cell concentration and zero growth rate. Toward the end of run 3 when the temperature was reduced by a total of 10°C in two 5°C increments, the cell concentration attained 4 × 1010 cells ml−1. The lowest csSRR values attained at the end of the runs were 0.10 ± 0.02, 0.016 ± 0.012, and 0.0017 ± 0.0003 fmol of SO42− cell−1 h−1.

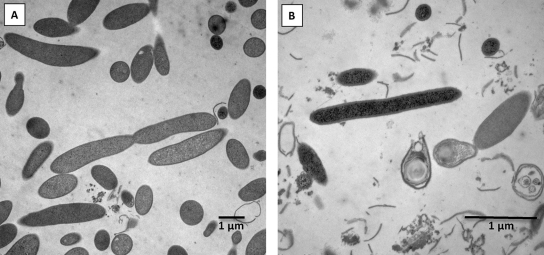

In runs 1 and 2, the cell concentrations declined briefly at the end of exponential growth (Fig. 3), indicating that some cell death process was occurring in these experiments, and this was seen by TEM. TEM observations also confirmed that dividing cells were more abundant in the samples collected prior to the onset of maintenance, were detected by the presence of lysed cells, indicated a reduction in cell volume from 4.9 to 0.5 μm3, and revealed the formation of endospores (Fig. 4). Spores comprised ∼10% of the total cell counts, and the csSRR values were corrected for this nonactive portion of the population.

FIG. 4.

(A) Transmission electron micrograph of D. putei cells at the end of exponential-phase growth (at 192 h) showing large healthy cells, one dividing cell, and a few smaller-diameter and denser cells. (B) Transmission electron micrograph of D. putei cells during maintenance metabolism (at 640 h) showing more smaller-diameter and denser cells, one larger cell, a couple of spores with spore coats, and remnants of cell walls and membranes.

Lipid analyses.

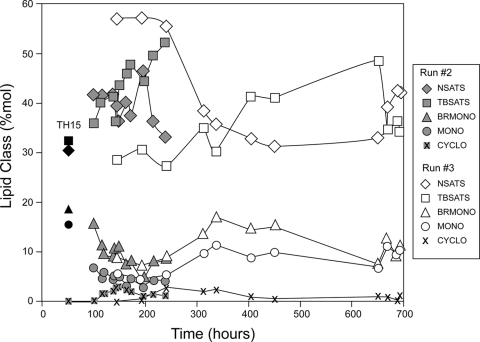

PLFA results were obtained for samples from the end of the exponential phase through the maintenance phase of runs 2 and 3 (Fig. 5). The total PLFA ranged from 286 to 2,470 pmol ml−1. These concentrations compared to the cell counts correspond to a cell number (pmol of PLFA−1) ratio of 2.7 × 107 with a ±1 S.D. of +3.3 × 107 and −1.6 × 107. This value is ∼1,000 times the 2.5 × 104 normally used for conversion of PLFA concentrations into cell concentrations (4). The PLFA composition was dominated by normal saturates (33 to 57%) and terminally branched saturates (29 to 52%), with the monoenoics comprising 3 to 11%, the branched monoenoics comprising 4 to 17%, and the one cyclic fatty acid present, 17:0 cyc, comprising only 0 to 3%. The relative proportions of the major fatty acid groups present in the retentostat experiment match those reported for D. putei (45), but the normal saturate abundance was somewhat higher and the monoenoics lower than those reported by Liu et al. (45). At the beginnings of runs 2 and 3, the proportions of normal saturates were greater than those of the terminally branched saturates, but further into the maintenance phase the terminally branch saturates became proportionally greater than the normal saturates, with the crossover occurring at ∼150 h for run 2 and ∼400 h for run 3 (Fig. 5). Toward the end of run 3, the proportions of terminally branched saturates decreased and of normal saturates increased as the temperature decreased from 65 to 55°C.

FIG. 5.

PLFA classes for runs 2 and 3 compared to the PLFA composition of D. putei (TH15) grown in batch culture (45) (solid symbols). NSATS, normal saturates; TBSATS, terminally branched saturates; BRMONO, branched monoenoics; MONO, monoenoics; CYCLO, cyclic fatty acid.

S isotope analyses.

The S mass balances for all aqueous sulfur species (SO42−, HS−, and S2O32−) in runs 2 and 3 remained within 7% and 10%, respectively, of the initial 20 mM SO42− pool. The S mass balance for run 1 could not be confirmed due to inaccurate HS− measurements. The S isotope mass balance for runs 2 and 3 as determined using equation 6 were ∼1‰ ± 1‰ greater than the S isotopic composition of the supply medium. Assuming that the isotopic composition of S2O32−, which was not determined, accounts for this small isotope imbalance, its δ34S values ranged from −55 to −100‰ and from −20 and −60‰ for runs 2 and 3, respectively.

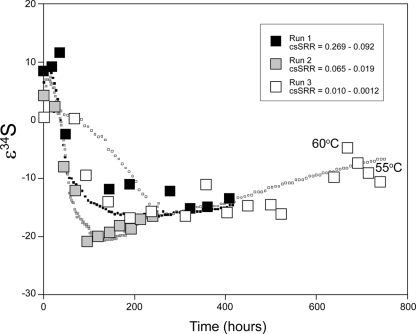

The ɛ34S values ranged from 12 to −15‰ during the course of run 1, with the most negative ɛ34S recorded at 408 h (Fig. 6). The ɛ34S values ranged from 5 to −21‰ during the course of run 2, with the most negative ɛ34S recorded at 95 h (Fig. 6). The ɛ34S values ranged from 1 to −18‰ during the course of run 3, with the most negative ɛ34S recorded at 192 h (Fig. 6). In the cases of runs 2 and 3, the most negative ɛ34S occurred just after the exponential phase and before the maintenance phase, and as the cells entered the state of maintenance metabolism, the ɛ34S steadily declined. This was most readily apparent in run 2, but run 3 exhibited an extension of the same trend. As the temperature dropped from 65 to 60°C, the ɛ34S changed from −15 to −5‰. As the temperature dropped from 60 to 55°C, the ɛ34S changed from −5 to −10‰.

FIG. 6.

ɛ34S was equal to δ34SHS minus  versus time during retentostat runs 1, 2, and 3. One standard deviation is 0.4‰, which is smaller than the symbol. Modeled enrichment curves are shown for runs 1 (small solid squares), 2 (small gray squares), and 3 (small open squares). The csSRR values are in fmol of SO42− cell−1 h−1. 60°C and 55°C, beginnings of temperature intervals for run 3.

versus time during retentostat runs 1, 2, and 3. One standard deviation is 0.4‰, which is smaller than the symbol. Modeled enrichment curves are shown for runs 1 (small solid squares), 2 (small gray squares), and 3 (small open squares). The csSRR values are in fmol of SO42− cell−1 h−1. 60°C and 55°C, beginnings of temperature intervals for run 3.

DISCUSSION

The retentostat cellular concentration profiles and substrate consumption curves correspond well with those found in previously published retentostat studies (47, 53, 58, 59, 62, 63), with the exception that distinct linear regions in the cellular concentration profiles were not readily discernible (Fig. 3). The average calculated maintenance coefficients during the final stages of runs 1, 2, and 3 were 4.7 × 10−17, 1.2 × 10−17, and 1.2 × 10−18 mol of lactate cell−1 h−1, respectively. These values are comparable to values reported for other non-SRB retentostat experiments run under conditions of electron donor limitation (18, 47, 62, 63). The 75-kJ (mol of SO42−)−1 ΔGp values are consistent with the net production of 1 mol of ATP per mol of SO42− but are less than the 23- and 35-kJ (mol of SO42−)−1 ΔGp values reported by Sonne-Hansen et al. (56) for H2-oxidizing, thermophilic SRB. The 75 kJ (mol of SO42−)−1 translates into a maintenance energy dissipation rate of ∼0.1 kJ C mol of biomass−1 h−1, which is ∼1,000 times less than values reported by Tijhuis et al. (60), which were based upon chemostat experiments.

Lactate oxidation during maintenance metabolism.

The 8 to 9 mM acetate concentrations observed during the maintenance phases of each experiment indicate that 16 to 18 mmol of organic carbon was produced for every 12 mmol of carbon from the 4 mmol of lactate added to the retentostat vessel. Simultaneously, 48 mmol of electrons is required to explain the reduction of 6 mmol of SO42− to HS− for every 4 mmol of lactate added to the retenotstat vessel. This observation suggests that complete oxidation of lactate with concomitant SO42− reduction occurred during the maintenance phase of D. putei. Batch culture experiments revealed the same reaction stoichiometry for SO42− reduction and a much smaller, but still discernible, excess acetate production, 4.4 mM of acetate produced per 4 mM of lactate consumed. For their batch culture experiments, Liu et al. (45) reported the incomplete conversion of lactate to acetate, but because the amount of SO42− reduced requires the complete oxidation of lactate, other potential origins for the acetate production were examined.

First, because the retentostat was being operated in an anaerobic glove bag, some residual H2 from the normal 10% H2-90% N2 headspace may have survived multiple purges by the 30% CO2-70% N2 gas. This H2 could then enter the retentostat through the supply medium and be utilized by D. putei for acetogenic pathways (4H2 + 2HCO3− + H+ → CH3COO− + 4H2O), thereby adding to the measured acetate pool and ultimately affecting the interpretation of the ɛ34S data due to mixed electron donor availability. This hypothesis seems unlikely, however, because of the following: (i) analyses of the glove bag headspace before exponential phase and during maintenance metabolism phase yielded 20 parts per million by volume H2 at both time points, indicating that H2 existed in the glove bag but had remained unconsumed throughout the course of the experiment; (ii) even if all of this H2 were consumed to produce acetate, given that the volume of the glove bag is ∼30 mol of gas, less than 1 mmol of acetate could be produced compared to the ∼52 mmol of acetate produced during run 3; (iii) at 65°C only submicromolar concentrations of the H2 would be dissolved in the medium, and this would be insufficient to account for the millimolar concentrations of acetate recorded; and (iv) excess acetate was observed in the batch culture where no H2 was added or detected.

Second, peptones in the fresh medium supply (see Materials and Methods) may have provided an alternate source of organic C to the system. Assuming that the 0.2% (by weight) peptones in the supply medium contained 40% organic C by weight (2) and that 100% of it was bioavailable and could subsequently contribute to acetate production via fermentation, as has been reported for other bacterial strains (50), then ∼33 mM could potentially result from this source compared to the 8 to 10 mM acetate concentrations observed. If true, this would mean that our calculated maintenance coefficients are minimum estimates.

Third, as cells are nutritionally deprived, they tend to shrink in order to maximize their surface area-to-volume ratio for increased transmembrane transport of nutrients, as well as for conservation of energy by limiting production of potentially superfluous macromolecules required for growth and cell division. Self-cannibalization could occur at this time, depleting intracellular carbon stores and once again producing acetate by direct substrate level phosphorylation. TEM observations revealed that cell size reduction did occur, with an increasing proportion of cells (Fig. 4B) being smaller than the cells of more normal size seen in the growth phase (Fig. 4A). Results of PLFA analyses are compatible with a change in membrane composition reflecting the change from vegetative cells (normal saturates dominate) to resting cells in maintenance metabolism (terminally branched saturates dominate) (Fig. 5).

Whether the last two processes have an effect on the ɛ34S results is uncertain, as the electron balance indicated that SO42− reduction occurred primarily by the complete oxidation of lactate.

S isotopic enrichment during maintenance metabolism.

The S mass balance results indicate that the S species were conserved for the duration of the retentostat run, and the ∼1‰ ± 1‰ S isotope mass imbalance that was based only on the δ34S of SO42− and HS− suggests that the δ34S of the S2O32− was more negative than that of the HS−. Theoretically, H2S comprises only 4.5% of the total sulfide at pH 7.8 and 65°C, and the theoretical equilibrium  is −1.1‰ and −1.2‰ for 65° and 55°C, respectively. The δ34S of the total sulfide, HS− + H2S, would be only 0.05 to 0.06‰ more negative than the values measured for HS−, and this falls within the error of measurement.

is −1.1‰ and −1.2‰ for 65° and 55°C, respectively. The δ34S of the total sulfide, HS− + H2S, would be only 0.05 to 0.06‰ more negative than the values measured for HS−, and this falls within the error of measurement.

The lowest csSRRs attained in our retentostat experiments are substantially lower than the lowest csSRRs reported in the literature for batch culture experiments. The lowest reported csSRR for a batch culture experiment was 2 × 10−17 mol cell−1 h−1 from a psychrophilic SRB strain incubated at −2°C (7), and this rate is 10 times higher than that of run 3. The lowest reported csSRR for a thermophilic batch culture experiment was 3 × 10−16 mol cell−1 h−1 for Desulfotomaculum geothermicum (22), which is 100 times higher than that of run 3. The lowest csSRR attained in our experiments, 1.7 × 10−8 mol of SO4 cell−1 h−1, is still 3 orders of magnitude higher than the in situ planktonic csSRR inferred from geochemical estimation (∼4 × 10−21 mol of SO4 cell−1 h−1) for the deep terrestrial subsurface of the Witwatersrand Basin (44) but is of the same magnitude as the csSRR measured by 35S microautoradiography for core-bound SRB (≥8 × 10−17 mol of SO4 cell−1 h−1) from the same environment (21).

The maximum ɛ34S attained during retentostat cultivation, −20.9‰ in run 2, is much greater than that for the batch culture performed with the same temperature, pH, and lactate/SO42− ratio, −9.7‰. The ɛ34S trends for all three experiments are similar, becoming increasingly negative during the exponential phase, attaining a peak negative value, which is then followed by a slow retreat from this peak negative value during the maintenance stage (Fig. 6). The decrease in ɛ34S during the exponential phase represents the combined effect of flushing and replacement of the initial HS− by microbially respired HS−. The decline in ɛ34S values during the maintenance stage (Fig. 6) cannot be attributed to changes in the membrane transport rates or HS− production rates as a function of temperature as outlined in the Canfield et al. (12) model for SO42− reduction, because the retentostat runs were isothermal in this region. The TEM data indicate that the cell surface-to-volume ratio increases from the end of the exponential stage to the maintenance stage. If vegetative cells express an inherently more negative ɛ34S than their resting cell counterparts, then one possible explanation for the slow decline in the magnitude of ɛ34S during the maintenance stage is the decrease in the number of vegetative cells and the increase in the number of resting cells. In order for the resting cells to yield a lesser ɛ34S than their vegetative progenitors, they would have to be more efficient in the conversion of intracellular SO42− to HS− rather than less efficient. The observed decrease and subsequent increase in the ɛ34S as the temperature was decreased at the end of run 3, on the other hand, could conceivably be related to temperature-dependent changes in the membrane transport and SO42− reduction rates as espoused by Canfield et al. (12) for their model.

The ɛ34S values during the maintenance stage did not exhibit any correlation the with S2O32− or HS− concentrations. Comparing the results from all three experiments, the ɛ34S values during the maintenance stage also did not exhibit any correlation with the csSRR across 3 orders of magnitude (Fig. 6). This was surprising given that the SO42− reduction pathway is the cumulative expression of multiple reductive and potentially reversible steps, each with its own ɛ34S (9, 12). By performing the retentostat experiments under electron donor-limited conditions and at a very low csSRR, we appear to have enhanced the reverse flow of S species in the cells as witnessed by the presence of S2O32− in the medium, and the inferred δ34S of the S2O32− is enriched in 32S by 20 to 100‰. These observations are compatible with the hypothesis of Brunner and Bernasconi (9) that the final reduction of SO32− to HS− is indeed a multistep process for D. putei. Although the retentostat experiments yielded greater ɛ34S values than did the batch culture, the final HS− product was still 40 to 50‰ less enriched in 32S than the 70‰ enhancement predicted by Brunner and Bernasconi (9). Further retentostat studies of SRB should be performed at lower temperatures to attain rates comparable to that in nature to fully test this theory.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Y. Liu of Portland State University for providing D. putei strain TH15. We also thank John Kessler of Princeton University for his assistance in the data analyses and interpretation and Ruth Droppo of Indiana University for assistance with preparation of the figures.

This research was supported by a National Science Foundation Continental Dynamics Program grant, EAR 0409605, to Zeev Reches, University of Oklahoma; by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant to G.S.; and by a NASA Astrobiology Institute grant through award NNA04CC03A to L.M.P.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbige, M., and W. R. Chesbro. 1982. relA and related loci are growth rate determinants for Escherichia coli in a recycling fermenter. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128:693-703. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas, R. M. 1993. Handbook of microbiological media. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 3.Baker, B. J., D. P. Moser, B. J. MacGregor, S. Fishbain, M. Wagner, N. K. Fry, B. Jackson, N. Speolstra, S. Loos, K. Takai, B. Sherwood-Lollar, J. K. Fredrickson, D. L. Balkwill, T. C. Onstott, C. F. Wimpee, and D. A. Stahl. 2003. Related assemblages of sulfate-reducing bacteria associated with ultradeep gold mines of South Africa and deep basalt aquifers of Washington state. Environ. Microbiol. 5:267-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balkwill, D., F. Leach, J. Wilson, J. McNabb, and D. White. 1988. Equivalence of microbial biomass measures based on membrane lipid and cell wall components, adenosine triphosphate, and direct counts in subsurface sediments. Microb. Ecol. 16:73-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bethke, C. M. 1998. The Geochemist's Workbench. A Users Guide to Rxn, Act2, Tact, React, and Gtplot. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign.

- 6.Bolliger, C., M. H. Schroth, S. M. Bernasconi, J. Kleikemper, and J. Zeyer. 2001. Sulfur isotope fractionation during microbial sulfate reduction by toluene-degrading bacteria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65:3289-3298. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruchert, V., C. Knoblauch, and B. B. Jorgensen. 2001. Controls on stable sulfur isotope fractionation during bacterial sulfate reduction in Arctic sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65:763-776. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruchert, V., and L. M. Pratt. 1996. Contemporaneous early diagenetic formation of organic and inorganic sulfur in estuarine sediments from St. Andrews Bay, Florida. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 60:2325-2332. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunner, V., and S. M. Bernasconi. 2005. A revised isotope fractionation model for dissimilatory sulfate reduction in sulfate reducing bacteria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69:4759-4771. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canfield, D. E. 1998. A new model for Proterozoic ocean chemistry. Nature 396:450-453. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canfield, D. E. 2001. Isotope fractionation by natural populations of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65:1117-1124. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canfield, D. E., C. A. Olesen, and R. P. Cox. 2006. Temperature and its control of isotope fractionation by a sulfate-reducing bacterium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70:548-561. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canfield, D. E., and R. Raiswell. 1999. The evolution of the sulfur cycle. Am. J. Sci. 299:697-723. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canfield, D. E., and A. Teske. 1996. Late Proterozoic rise in atmospheric oxygen concentration inferred from phylogenetic and sulphur-isotope studies. Nature 382:127-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canfield, D. E., and B. Thamdrup. 1994. The production of 34S-depleted sulfide during bacterial disproportionation of elemental sulfur. Science 266:1973-1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambers, L. A., and P. A. Trudinger. 1975. Are thiosulfate and trithionate intermediates in dissimilatory sulfate reduction? J. Bacteriol. 123:36-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chambers, L. A., P. A. Trudinger, J. W. Smith, and M. S. Burns. 1975. Fractionation of sulfur isotopes by continuous cultures of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Can. J. Microbiol. 21:1602-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colwell, F. S., S. Boyd, M. E. Delwiche, D. W. Reed, T. J. Phelps, and D. T. Newby. 2008. Estimates of biogenic methane production rates in deep marine sediments at Hydrate Ridge, Cascadia Margin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3444-3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cord-Ruwisch, R. 1985. A quick method for the determination of dissolved and precipitated sulfides in cultures of sulfate-reducing bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 4:33-36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cypionka, H. 1995. Solute transport and cell energetics, p. 151-184. In L. L. Barton (ed.), Sulfate-reducing bacteria. Biotechnology handbooks, vol. 8. Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson, M. M. 2008. Sulfate reduction in the deep terrestrial subsurface: a study of microbial ecology, metabolic rates and sulfur isotope fractionation. Ph.D. dissertation. Princeton University, Princeton, NJ.

- 22.Detmers, J., V. Brüchert, K. S. Habicht, and J. Kuever. 2001. Diversity of sulfur isotope fractionation by sulfate-reducing prokaryotes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:888-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Hondt, S., S. Rutherford, and A. J. Spivack. 2002. Metabolic activity of subsurface life in deep-sea sediments. Science 295:2067-2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding, T., H. Valkiers, H. Kipphards, P. De Bièvre, P. D. P. Taylor, R. Gonfiantini, and R. Krouse. 2001. Calibrated sulfur isotope abundance ratios of three IAEA sulfur isotope reference materials and V-CDT with a reassessment of the atomic weight of sulfur. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65:2433-2437. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitz, R. M., and H. Cypionka. 1990. Formation of thiosulfate and trithionate during sulfite reduction by washed cells of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Arch. Microbiol. 154:400-406. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gihring, T. M., D. P. Moser, L.-H. Lin, M. Davidson, T. C. Onstott, L. Morgan, M. Milleson, T. Kieft, E. Trimarco, D. L. Balkwill, and M. Dollhopf. 2006. The distribution of microbial taxa in the subsurface water of the Kalahari Shield, South Africa. Geomicrobiol. J. 23:415-430. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habicht, K. S., and D. E. Canfield. 2001. Isotope fractionation by sulfate reducing natural populations and the isotopic composition of sulfide in marine sediments. Geology 29:555-558. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habicht, K. S., and D. E. Canfield. 1997. Sulfur isotope fractionation during bacterial sulfate reduction in organic-rich sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61:5351-5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Habicht, K. S., D. E. Canfield, and J. Rethmeier. 1998. Sulfur isotope fractionation during bacterial reduction and disproportionation of thiosulfate and sulfite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 62:2585-2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habicht, K. S., L. Salling, B. Thamdrup, and D. E. Canfield. 2005. Effect of low sulfate concentrations on lactate oxidation and isotope fractionation during sulfate reduction by Archaeoglobus fulgidus strain Z. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3770-3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrison, A. G., and H. G. Thode. 1958. Mechanism of the bacterial reduction of sulfate from isotope fractionation studies. Trans. Faraday Soc. 54:84-92. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoek, J., A.-L. Reysenbach, K. S. Habicht, and D. E. Canfield. 2006. Effect of hydrogen limitation and temperature on the fractionation of sulfur isotopes by a deep-sea hydrothermal vent sulfate-reducing bacterium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70:5831-5841. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ingvorsen, K., and B. B. Jorgensen. 1984. Kinetics of sulfate uptake by fresh-water and marine species of Desulfovibrio. Arch. Microbiol. 139:61-66. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin, Q. S., and C. M. Bethke. 2003. A new rate law describing microbial respiration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2340-2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin, Q. S., and C. M. Bethke. 2005. Predicting the rate of microbial respiration in geochemical environments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69:1133-1143. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jørgensen, B. B. 1990. A thiosulfate shunt in the sulfur cycle of marine sediments. Science 249:152-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jørgensen, B. B., and S. D'Hondt. 2006. A starving majority deep beneath the seafloor. Science 314:932-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaplan, I. R., and S. C. Rittenberg. 1964. Microbial fractionation of sulfur isotopes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 34:195-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kemp, A. L. W., and H. G. Thode. 1968. The mechanism of bacterial reduction of sulfate and of sulfite from isotope fractionation studies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 32:71-91. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleikemper, J., M. H. Schroth, S. M. Bernasconi, B. Brunner, and J. Zeyer. 2004. Sulfur isotope fractionation during growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria on various carbon sources. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68:4891-4904. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobayashi, K., Y. Seki, and M. Ishimoto. 1974. Biochemical studies on sulfate-reducing bacteria. XIII. Sulfite reductase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris—mechanism of trithionate, thiosulfate, and sulfide formation and enzymatic properties. J. Biochem. 75:519-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobayashi, K., E. Takahashi, and M. Ishimoto. 1972. Biochemcial studies on sulfate-reducing bacteria. XI. Purification and some properties of sulfite reductase, desulfoviridin. J. Biochem. 72:879-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LaRowe, D. E., and H. C. Helgeson. 2007. Quantifying the energetics of metabolic reactions in diverse biogeochemical systems: electron flow and ATP synthesis. Geobiology 5:153-168. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin, L. H., P.-L. Wang, D. Rumble, J. Lippmann-Pipke, E. Boice, L. M. Pratt, B. Sherwood Lollar, E. Brodie, T. Hazen, G. Andersen, T. DeSantis, D. P. Moser, D. Kershaw, and T. C. Onstott. 2006b. Long-term biosustainability in a high-energy, low-diversity crustal biome. Science 314:479-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu, Y., T. M. Karnauchow, K. F. Jarrell, D. L. Balkwill, G. R. Drake, D. Ringelberg, R. Clarno, and D. R. Boone. 1997. Description of two new thermophilic Desulfotomaculum spp., Desulfotomaculum putei sp. nov., from a deep terrestrial subsurface, and Desulfotomaculum luciae sp. nov., from a hot spring. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:615-621. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moser, D. P., T. M. Gihring, F. J. Brockman, J. K. Fredrickson, D. L. Balkwill, M. E. Dollhopf, B. Sherwood Lollar, L. M. Pratt, E. A. Boice, G. Southam, G. Wanger, B. J. Baker, S. M. Pfiffner, L.-H. Lin, and T. C. Onstott. 2005. Desulfotomaculum spp. and Methanobacterium spp. dominate a 4- to 5-kilometer-deep fault. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8773-8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Müller, R. H., and W. Babel. 1996. Measurement of growth at very low rates (μ = 0), an approach to study the energy requirement for the survival of Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP 134. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:147-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Onstott, T. C., L.-H. Lin, M. Davidson, B. Mislowack, M. Borcsik, J. Hall, G. Slater, J. Ward, B. Sherwood Lollar, J. Lippmann-Pipke, E. Boice, L. M. Pratt, S. Pfiffner, D. P. Moser, T. Gihring, T. Kieft, T. J. Phelps, E. van Heerden, D. Litthaur, M. DeFlaun, and R. Rothmel. 2006. The origin and age of biogeochemical trends in deep fracture water of the Witwatersrand Basin, South Africa. Geomicrobiol. J. 23:369-414. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parkes, R. J., B. A. Cragg, J. C. Fry, R. A. Herbert, and J. W. T. Wimpenny. 1990. Bacterial biomass and activity in deep sediment layers from the Peru margin. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 331:139-153. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rogosa, M. 1969. Acidaminococcus gen. n., Acidaminococcus fermentans sp. n., anaerobic gram-negative diplococci using amino acids as the sole energy source for growth. J. Bacteriol. 98:756-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudnicki, M. D., H. Elderfield, and B. Spiro. 2001. Fractionation of sulfur isotopes during bacterial sulfate reduction in deep ocean sediments at elevated temperatures. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65:777-789. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sass, H., J. Steuber, M. Kroder, P. M. H. Kroneck, and H. Cypionka. 1992. Formation of thionates by freshwater and marine strains of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 158:418-421. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schrickx, J. M., A. S. Krave, J. C. Verdoes, C. A. M. J. J. van dan Hondel, A. H. Stouthamer, and H. W. van Verseveld. 1993. Growth and product formation in chemostat and recycling cultures by Aspergillus niger N402 and a glucoamylase overproducing transformant, provided with multiple copies of the glaA gene. J. G. Microbiol. 139:2801-2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen, Y., and R. Buick. 2004. The antiquity of microbial sulfate reduction. Earth Science Rev. 64:243-272. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shen, Y., R. Buick, and D. E. Canfield. 2001. Isotopic evidence for microbial sulphate reduction in the early Archaean era. Nature 410:77-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sonne-Hansen, J., P. Westermann, and B. K. Ahring. 1999. Kinetics of sulfate and hydrogen uptake by the thermophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria Thermodesulfobacterium sp. strain JSP and Thermodesulfovibrio sp. strain R1Ha3. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1304-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Studley, S. A., E. M. Ripley, E. R. Elswick, M. J. Dorais, J. Fong, D. Finkelstein, and L. M. Pratt. 2002. Analysis of sulfides in whole rock matrices by elemental analyzer-continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Chem. Geol. 192:141-148. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tappe, W., A. Laverman, M. Bohland, M. Braster, S. Rittershaus, J. Groeneweg, and H. W. van Verseveld. 1999. Maintenance energy demand and starvation recovery dynamics of Nitrosomonas europaea and Nitrobacter winogradskyi cultivated in a retentostat with complete biomass retention. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2471-2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tappe, W., C. Tomaschewski, S. Rittershaus, and J. Groeneweg. 1996. Cultivation of nitrifying bacteria in the retentostat, a simple fermenter with internal biomass retention. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 19:47-52. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tijhuis, L., M. C. M. van Loosdrecht, and J. J. Heijnen. 1993. A thermodynamically based correlation for maintenance gibbs energy requirements in aerobic and anaerobic chemotrophic growth. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 42:509-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trimarco, E., D. L. Balkwill, M. M. Davidson, and T. C. Onstott. 2006. In situ enrichment of a diverse community of bacteria from a 4-5 km deep fault zone in South Africa. Geomicrobiol. J. 23:463-473. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tros, M. E., T. N. Bosma, G. Schraa, and A. B. Zehnder. 1996. Measurement of minimum substrate concentration (Smin) in a recycling fermentor and its prediction from the kinetic parameters of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 from batch and chemostat cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3655-3661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Verseveld, H. W., J. A. De Hollander, J. Frankena, M. Braster, F. J. Leeuwerik, and A. H. Stouthamer. 1984. Modeling of microbial substrate conversion, growth and product formation in the recycling fermenter. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 52:325-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Werne, J. P., T. W. Lyons, D. J. Hollander, M. J. Formolo, and J. S. S. Damsté. 2003. Reduced sulfur in euxinic sediments of the Cariaco Basin: sulfur isotope constraints on organic sulfur formation. Chem. Geol. 195:159-179. [Google Scholar]

- 65.White, D. C., and D. B. Ringelberg. 1998. Signature lipid biomarker analysis. In R. S. Burlage, R. Atlas, D. A. Stahl, G. Geesey, and G. Sayler (ed.), Techniques in microbial ecology. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

- 66.Widdel, F., and T. A. Hansen. 1992. The dissimilatory sulfate- and sulfur-reducing bacteria, p. 583-624. In A. Balows, H. G. Truper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, and K. H. Schleifer (ed.), The prokaryotes, vol. 1. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wortmann, U. G., S. M. Bernasconi, and M. E. Bottcher. 2001. Hypersulfidic deep biosphere indicates extreme sulfur isotope fractionation during single-step microbial sulfate reduction. Geology 29:647-650. [Google Scholar]