Abstract

The transcription factor DksA binds in the secondary channel of RNA polymerase (RNAP) and alters transcriptional output without interacting with DNA. Here we present a quantitative assay for measuring DksA binding affinity and illustrate its utility by determining the relative affinities of DksA for three different forms of RNAP. Whereas the apparent affinities of DksA for RNAP core and holoenzyme are the same, the apparent affinity of DksA for RNAP decreases almost 10-fold in an open complex. These results suggest that the conformation of RNAP present in an open complex is not optimal for DksA binding and that DNA directly or indirectly alters the interface between the two proteins.

Transcription of rRNA accounts for the majority of RNA synthesis in Escherichia coli at high growth rates, but rRNA transcription decreases under less favorable nutritional conditions, primarily from regulation by two small molecules, ppGpp and the initial NTP in the transcript (11, 15). Current models suggest that the 151-amino-acid protein DksA binds directly to RNA polymerase (RNAP) and modifies the kinetic properties of the promoter complex, sensitizing it to changes in the concentrations of ppGpp and the initial NTP in the transcript (13). Consistent with this model, mutants lacking dksA fail to reduce rRNA transcription at low steady-state growth rates, after amino acid starvation, and as cells enter stationary phase (13). Although the concentration of DksA itself does not appear to vary, overproduction of DksA can further decrease rRNA transcription in vivo, and high concentrations of DksA by itself can inhibit promoter activity in the absence of ppGpp in vitro (7, 13, 17, 19). These results suggest that DksA concentrations are not saturating for control of rRNA promoters under normal conditions and that the requirement for dksA for regulation of rRNA synthesis in vivo is tied to its ability to act synergistically with the small molecules.

Although its role in regulation of rRNA transcription has been studied in the greatest detail, DksA affects many other promoters as well (5, 7, 15). Direct effects of DksA can be either negative or positive. DksA not only inhibits promoters responsible for expressing rRNAs, many tRNAs, the transcription factor Fis, and many other gene products (5, 7, 8, 13, 17) but also directly stimulates transcription from a variety of promoters. These include some promoters needed for amino acid biosynthesis and/or transport (14), the promoter responsible for synthesis of the mRNA binding protein Hfq (21), and some promoters recognized by holoenzymes containing alternative sigma factors (3).

Unlike conventional transcription factors, DksA does not bind to DNA, and it interacts with promoter complexes by binding directly to RNAP (13, 16). DksA resembles the transcription elongation factors GreA and GreB in overall size and in the structure of its coiled-coil domain (16). Like these factors, DksA binds in the secondary channel of RNAP (12, 16, 19; I. Toulokhonov and R. L. Gourse, unpublished). DksA affects transcription initiation allosterically, disrupting RNAP-DNA interactions at least 25 Å away from its site of interaction with RNAP and shortening the half-life of one of the transcription initiation intermediates formed by RNAP on the pathway to open-complex formation (20).

In order to address the mechanism of DksA action further, we have developed a quantitative assay for measuring the affinity of DksA for RNAP. This assay facilitates genetic approaches to DksA function, e.g., it allows distinction between residues in DksA or RNAP that are needed specifically for binding and/or for subsequent steps in the mechanism of DksA action. Furthermore, we show here that the assay allows comparison of the binding affinities of DksA for free RNAP and for promoter complexes.

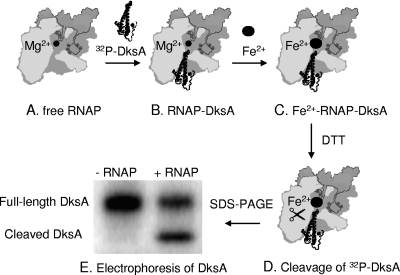

The DksA binding assay (pictured schematically in Fig. 1) is an adaptation of a previously described method used to demonstrate the proximity of the transcription factors GreA and GreB to the RNAP active center (6). In this assay, an active-site Mg2+ is replaced by ferrous iron, generating hydroxyl radicals upon addition of dithiothreitol (DTT) (22). The hydroxyl radicals cleave the coiled-coil tip of bound DksA, localizing it to within ∼10 Å of the RNAP active site, the limit of hydoxyl radical diffusion (16, 20; Toulokhonov and Gourse, unpublished). The assay has not been adapted previously for measuring binding affinities of transcription factors for RNAP.

FIG. 1.

Localized Fe2+-mediated, RNAP-dependent cleavage of 32P-labeled HMK-His6 DksA. (A) Free RNAP with Mg2+ (sphere) at the catalytic center. (B) 32P-labeled HMK-His6 DksA binds in the secondary channel of RNAP holoenzyme. (C and D) The active-site Mg2+ in RNAP is replaced by Fe2+ (C), and DTT generates hydroxyl radicals that cleave the coiled-coil tip of DksA (D) (Fe2+ addition and DTT addition are pictured as sequential steps for purposes of illustration but were actually performed simultaneously). (E) Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) profile of DksA in the absence (−) and presence (+) of RNAP. For more detailed representations of the RNAP holoenzyme, see references 5, 9, and 10.

Standard binding assays, such as gel shifts, were unreliable in our preliminary attempts to measure the affinity of DksA for RNAP (data not shown), perhaps because the DksA-RNAP interaction is transient and most assays require that complexes persist over time (e.g., during electrophoresis). In contrast, the localized iron-mediated cleavage assay does not require formation of complexes with long lifetimes, it does not require separation of complexes from the free reactants, and it allows measurements to be made in solution. Finally, because it demands positioning of the DksA coiled coil at its functionally significant site (within ∼10 Å of the active site), binding events in which DksA might interact only with the periphery of RNAP would not be scored as positive in this assay.

HMK-His6 DksA binds to RNAP like wild-type DksA in vivo and in vitro.

A vector expressing an N-terminally heart muscle kinase (HMK)-tagged, histidine (His6)-tagged DksA was constructed by inserting the dksA gene into pET33 to form pRLG8150 (20), and the protein was overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen). The resulting protein contains 25 extra amino acids at its N terminus compared to wild-type DksA (5 more residues at its N terminus than the His6 version described previously) (13). HMK-His6 DksA was purified by metal affinity chromatography (13).

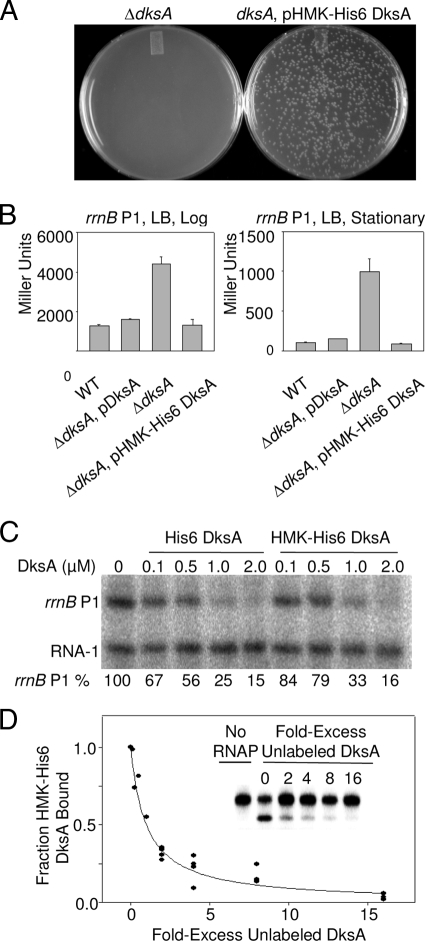

His6 DksA is indistinguishable in function from wild-type DksA both in vitro and in vivo (13). Tests were performed to ensure that HMK-His6 DksA was also indistinguishable from the native protein in function. First, we showed that HMK-His6 DksA encoded by a plasmid complemented a ΔdksA mutant strain, allowing growth on a medium lacking amino acids (Fig. 2A) (13, 20). Second, plasmid-encoded HMK-His6 DksA reduced the activity of an rrnB P1 promoter-lacZ fusion in a ΔdksA mutant strain, returning rrnB P1 activity to the same level as in wild-type cells and as in ΔdksA cells complemented with wild-type DksA (Fig. 2B). Third, purified HMK-His6 DksA inhibited transcription from the rrnB P1 promoter in vitro, with a concentration dependence similar to that for His6 DksA (Fig. 2C). The RNA-1 promoter was not affected by DksA, indicating that HMK-His6 DksA acts promoter specifically. Taken together, the data shown in Fig. 2A to C indicate that HMK-His6 DksA functions like native DksA.

FIG. 2.

HMK-His6 DksA binds to RNAP like wild-type DksA in vivo and in vitro. (A) HMK-His6 DksA complements a ΔdksA mutant strain for growth on M9 minimal medium with 0.4% glycerol and without amino acids. HMK-His6 DksA was produced from plasmid pRLG9511 (20). (B) HMK-His6 DksA reduces rrnB P1 promoter activity to the same extent as in cells containing native DksA. β-Galactosidase activities (in Miller units) in strains containing rrnB P1 promoter-lacZ fusions (promoter sequence endpoint, −61 to +1) in log phase (left) and stationary phase (right) were determined as described previously (19). Cells were grown at 30°C in LB medium. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Wild type (WT), RLG5950; ΔdksA, RLG7062. (C) HMK-His6 DksA inhibits rRNA promoter activity in vitro. The amount of transcript from the rrnB P1 promoter is indicated below each lane as a percentage of that without DksA. RNAP (10 nM) and DksA (at the indicated concentrations) were added to plasmid pRLG5944 containing the rrnB P1 promoter (sequence endpoints, −61 to +1) and the RNA-1 promoter. Transcripts are indicated. Single-round transcription reactions were performed as described previously (1). The buffer contained 50 mM NaCl. The assay was performed multiple times with similar results, and results from a representative experiment are shown. (D) Unlabeled HMK-His6 DksA competes with 32P-labeled HMK-His6 DksA for RNAP-dependent, Fe2+-mediated cleavage of DksA. The RNAP holoenzyme concentration was 0.1 μM, the 32P-DksA concentration was 1 μM, and the amounts of excess unlabeled DksA are indicated on the x axis. The curve was generated from five independent experiments in which the fraction of DksA cleaved in each experiment in the absence of unlabeled DksA (typically ∼30% of input 32P-DksA) was normalized to 1.0. Inset, representative gel from a single experiment in which 0, 2, 4, 8, or 16 μM unlabeled DksA was added to 1 μM 32P-labeled DksA and 0.1 μM RNAP holoenzyme for 5 min before addition of DTT to initiate DksA cleavage.

Purified HMK-His6-tagged DksA was 32P labeled as described previously (20). The buffer was then replaced with buffer A (20 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl) by two passes through a G-50 QuickSpin column (GE Healthcare). RNAP core and holoenzyme were purified by standard procedures (2, 4), and the storage buffer was replaced with buffer A. The concentrations of both DksA and RNAP were then determined using a protein dye reagent assay (Bio-Rad).

For localized iron-mediated cleavage of DksA, 32P-labeled DksA was added to RNAP for 5 min in buffer A at 30°C. Cleavage was initiated by addition of a mixture of 1 μl of freshly prepared 500 μM (NH4)2-Fe(SO4)2 and 1 μl of 100 mM DTT to the 10-μl reaction mixture for 10 min. (Control time course experiments indicated that cleavage was maximal by this time [data not shown].) The reaction was stopped with 12 μl of 2× lithium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer (Invitrogen) containing glycerol, electrophoresis was performed on 4 to 12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels using MES [2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid] buffer (Invitrogen), and the results were analyzed by phosphorimaging. Appearance of the cleaved product was dependent on the presence of Fe2+, DTT, and RNAP (data not shown).

Competition experiments between 32P-labeled HMK-His6 DksA and unlabeled His6 DksA (data not shown) or unlabeled HMK-His6 DksA (Fig. 2D) confirmed that phosphorylation had no effect on the affinity of DksA for RNAP. When RNAP was limiting (10-fold excess of DksA over RNAP prior to addition of unlabeled DksA competitor), the fraction of 32P-DksA cleaved decreased as a function of increasing DksA competitor. The addition of equimolar concentrations of unlabeled DksA decreased cleavage by 50%. Thus, the decrease in the cleaved fraction of DksA fit the prediction for simple competition.

RNAP core and holoenzyme bind DksA with the same affinity.

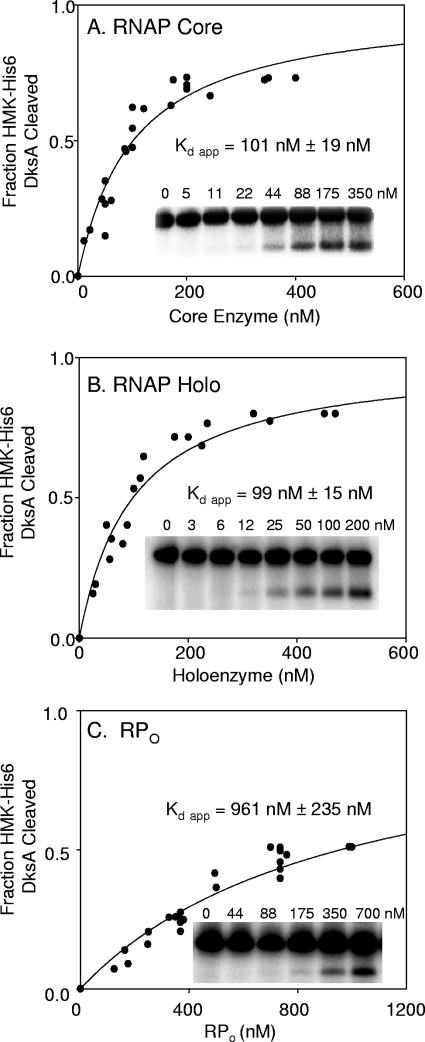

To measure the affinity of DksA for various forms of RNAP (Fig. 3), the concentration of 32P-labeled DksA was kept constant, and the concentration of RNAP was varied (see the legend for Fig. 3 for concentrations). The molar concentration of RNAP was always at least threefold higher than that of DksA. The fraction of DksA cleaved was then calculated at each RNAP concentration by dividing the amount of radioactivity in the band of cleaved DksA by the sum of the cleaved and uncleaved DksA. As predicted for a pseudo-first-order reaction, the fraction cleaved was dependent only on the concentration of RNAP and not on that of DksA (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Binding curves for DksA with different forms of RNAP. Fe2+-mediated cleavage assays were performed using 32P-DksA and increasing amounts of RNAP. RNAP was in the form of core enzyme (A), holoenzyme (Holo) (Eσ70) (B), and heparin-resistant open complex (C). The DksA concentration was 1 nM for panels A and B or 10 nM for panel C. Each point represents the result for a single reaction from a single experiment. Results from at least six independent experiments were plotted together after normalization to the maximum fraction of DksA cleaved in each experiment. The apparent Kd (Kd app) represents the concentration of RNAP at which half-maximal cleavage of DksA was obtained (see the text for a discussion of the computational analysis). Insets, gel images from single representative experiments.

Data were fit using the equation for ligand binding, one-site saturation, in SigmaPlot 10.0 to estimate the saturation value and the apparent Kd (dissociation constant). Cleavage of DksA saturated at ∼30% of total DksA under these conditions (Fig. 3A and B, insets). The basis for the less-than-complete cleavage of DksA is uncertain. However, because the DksA coiled-coil tip represents a small target, DksA is bound to RNAP only transiently, and hydroxyl radicals generated at the active center diffuse in all directions, most radicals are quenched either by solvent or by sites on RNAP. Therefore, perhaps it is not surprising that only a minority of the DksA population is cleaved.

The binding curves are shown in Fig. 3A and B. The apparent binding constants were determined from the equation Kd = [DksA]f × [RNAP]f/[DksA-RNAP]c, where [DksA]f, [RNAP]f, and [DksA-RNAP]c are the concentrations of free DksA, free RNAP, and the complex, respectively. The apparent binding constants for DksA binding to RNAP core enzyme and holoenzyme were the same within error, 101 nM ± 19 nM and 99 nM ± 15 nM, respectively. These results suggest that σ70 does not influence DksA binding.

RPO binds DksA more weakly than free RNAP.

To measure binding of DksA to RNAP holoenzyme in an open complex (RPO), we utilized a promoter that contains a perfect consensus DNA sequence for recognition by Eσ70. This “full-con” promoter (4) was chosen because it makes open complexes that are stable for many hours, much longer than the duration of the assay. The potential for contamination with free RNAP was reduced still further by removal of free RNAP with heparin beads (see below). Using a promoter that made a very stable complex and treatment of the complexes with heparin beads ensured that the estimate of the DksA binding constant for RPO would not be compromised by the presence of free RNAP in the reaction mixture.

The full-con promoter DNA fragment was generated by PCR from pRLG3749 (4), a pRLG770 derivative (18) containing promoter positions −54 to +16 with respect to the transcription start site as well as 94 bp of flanking DNA. The DNA fragment was always in at least twofold stoichiometric excess over RNAP at all RNAP concentrations. After addition of DNA, heparin beads (100 μg/ml final; Thermo Scientific) were added to remove any unbound RNAP, and then the beads were removed by microcentrifugation (1 min). The buffer was replaced with buffer A (see above) by two passes through a G-50 QuickSpin column, and the protein concentration was determined using a protein dye reagent assay (Bio-Rad).

The amount of DksA cleavage product generated by binding to RPO was ∼10% of the amount of input DksA at the highest RNAP concentration tested (Fig. 3C, inset), sufficient to allow determination of an apparent Kd but lower than the ∼30% plateau level typically obtained with free RNAP holoenzyme (Fig. 3B; also see the legend for Fig. 2D). When we employed the same analysis as for free RNAP core and holoenzyme, the binding constant obtained for DksA with RPO was 961 nM ± 235 nM (Fig. 3C), almost 10-fold weaker than that obtained with free RNAP.

If our RPO preparation were contaminated with free RNAP, the difference in the apparent DksA binding constants for free RNAP versus RPO would have been even greater. To estimate the potential level of contamination with free RNAP, we analyzed the composition of our purified complex by native gel electrophoresis (data not shown). Under conditions in which contamination with 1% free RNAP would have been detected easily, we observed no free RNAP in our RPO preparation. We calculated that if there was as much as 1% free RNAP in our preparation, the real Kd of RPO would be 1,300 nM.

The low fraction of cleaved DksA with RPO likely resulted from at least two considerations. First, as indicated in Fig. 3C, the amount of RPO at the highest concentration tested (1,500 nM) was not quite saturating (technical considerations limited the use of concentrations of RPO high enough to reach full saturation). Our inability to achieve a plateau for binding experimentally resulted in a higher degree of error in the calculated value of the apparent Kd for DksA binding to RPO than to the value for binding to core and holoenzyme. Second, the level of cleavage of DksA in RPO was decreased by chelation of Fe2+ by DNA. Consistent with this interpretation, the addition of more Fe2+ increased the fraction of DksA cleaved but did not affect the concentration of RNAP at which half-maximal cleavage was observed (data not shown). We therefore added a gross excess of full-con promoter DNA (3 μM) to all reaction mixtures containing RPO to sequester the same amount of Fe2+ in each.

The increase in the apparent Kd of DksA for RPO relative to that for free RNAP indicates that promoter DNA changes the conformation of RNAP, directly or indirectly altering the RNAP-DksA interface. The apparent Kd for RPO binding to DksA reported here is similar to that obtained from estimates based on assays of DksA function, i.e., effects of DksA on transcription or on complex half-life (20). The apparent affinity of DksA for RPO reported here is also well within the range where binding of DksA to RPO would be expected to occur in vivo, considering the absolute concentrations of DksA estimated in cells (13, 19). The concentration of DksA was held constant in the assay described here, and the concentration of RNAP was varied. In contrast, the RNAP concentration was fixed and the DksA concentration was varied in the measurements of binding based on DksA function (20). Thus, our results confirm that apparent Kd estimates can be made by varying either RNAP or DksA.

Future directions.

DksA overexpression in vivo increases the effect of DksA on rRNA promoter activity. Therefore, the concentration of DksA is not saturating for effects on transcription initiation in cells (17, 19), and differences in affinity of DksA for free RNAP versus RPO could differentially affect free versus promoter-bound RNAP in vivo. Further investigations will address the potential for the promoter sequence to affect DksA binding differentially and the nature of the DNA-induced RNAP conformational changes that modulate the binding of DksA. Although we have restricted our studies to the effects of DksA on transcription initiation, DksA also binds to RNAP during elongation (16), and the presence of DNA could affect DksA occupancy of the RNAP core enzyme at this step in transcription. We note that this assay also could be adapted for the analysis of interactions between GreA or GreB and RNAP.

In summary, we have developed a localized Fe2+-mediated, RNAP-dependent cleavage assay to determine the apparent affinity of DksA for RNAP. We illustrate the utility of the assay here by demonstrating that DksA binds with equal affinities to RNAP core and holoenzyme and that promoter DNA significantly decreases the affinity of DksA for RNAP. We are using this assay for the analysis of DksA and RNAP variants in structure-function studies of the mechanism of DksA action. For example, DksA mutants (bearing substitution L15F or N88I) that inhibit rRNA promoter activity more strongly than wild-type DksA in vivo and in vitro were identified recently (1). The assay described here allowed us to determine that the increased activities of these mutants resulted primarily from an increase in DksA binding affinity.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Toulokhonov for construction of the HMK-His6 DksA expression plasmid, R. Saecker for help with data analysis, and S. Borukhov for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the National Institutes of Health to C.W.L. and an NIH research grant (R37 GM37048) to R.L.G.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blankschien, M. D., J.-H. Lee, E. A. Grace, C. W. Lennon, J. A. Halliday, W. Ross, R. L. Gourse, and C. Herman. 2009. Super DksAs: substitutions in DksA enhancing its effects on transcription initiation. EMBO J. 281720-1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgess, R. R., and J. J. Jendrisak. 1975. Procedure for the rapid, large-scale purification of Escherichia coli DNA-dependent RNA polymerase involving polymin P precipitation and DNA-cellulose chromatography. Biochemistry 144634-4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costanzo, A., H. Nicoloff, S. E. Barchinger, A. B. Banta, R. L. Gourse, and S. E. Ades. 2008. ppGpp and DksA likely regulate the activity of the extracytoplasmic stress factor sigma E in Escherichia coli by both direct and indirect mechanisms. Mol. Microbiol. 67619-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaal, T., W. Ross, S. T. Estrem, L. H. Nguyen, R. R. Burgess, and R. L. Gourse. 2001. Promoter recognition and discrimination by EσS RNA polymerase. Mol. Microbiol. 42939-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haugen, S. P., W. Ross, and R. L. Gourse. 2008. Advances in bacterial promoter recognition and its control by factors that do not bind DNA. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6507-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laptenko, O., J. Lee, I. Lomakin, and S. Borukhov. 2003. Transcript cleavage factors GreA and GreB act as transient catalytic components of RNA polymerase. EMBO J. 226322-6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnusson, L. U., B. Gummesson, P. Jaksimović, A. Farewell, and T. Nyström. 2007. Identical, independent, and opposing roles of ppGpp and DksA in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1895193-5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallik, P., B. J. Paul, S. T. Rutherford, R. L. Gourse, and R. Osuna. 2006. DksA is required for growth phase-dependent regulation, growth rate-dependent control, and stringent control of fis expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1885775-5782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murakami, K. S., and S. A. Darst. 2003. Bacterial RNA polymerases: the wholo story. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1331-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami, K. S., S. Masuda, E. A. Campbell, O. Muzzin, and S. A. Darst. 2002. Structural basis of transcription initiation: an RNA polymerase holoenzyme-DNA complex. Science 2961285-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray, H. D., D. A. Schneider, and R. L. Gourse. 2003. Control of rRNA expression by small molecules is dynamic and nonredundant. Mol. Cell 12125-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opalka, N., M. Chlenov, P. Chacon, W. J. Rice, W. Wriggers, and S. A. Darst. 2003. Structure and function of the transcription elongation factor GreB bound to bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell 114335-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul, B. J., M. M. Barker, W. Ross, D. A. Schneider, C. Webb, J. W. Foster, and R. L. Gourse. 2004. DksA: a critical component of the transcription initiation machinery that potentiates the regulation of rRNA promoters by ppGpp and the initiating NTP. Cell 118311-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul, B. J., M. M. Berkmen, and R. L. Gourse. 2005. DksA potentiates direct activation of amino acid promoters by ppGpp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1027823-7828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul, B. J., W. Ross, T. Gaal, and R. L. Gourse. 2004. rRNA transcription in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38749-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perederina, A., V. Svetlov, M. N. Vassylyeva, T. H. Tahirov, S. Yokoyama, I. Artsimovitch, and D. G. Vassylyev. 2004. Regulation through the secondary channel-structural framework for ppGpp-DksA synergism during transcription. Cell 118297-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potrykus, D., D. Vinella, H. Murphy, A. Szalewska-Palasz, R. D'Ari, and M. Cashel. 2006. Antagonistic regulation of Escherichia coli ribosomal RNA rrnB P1 promoter activity by GreA and DksA. J. Biol. Chem. 28115238-15248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross, W., J. F. Thompson, J. T. Newlands, and R. L. Gourse. 1990. E. coli Fis protein activates ribosomal RNA transcription in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J. 93733-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rutherford, S. T., J. J. Lemke, C. E. Vrentas, T. Gaal, W. Ross, and R. L. Gourse. 2007. Effects of DksA, GreA, and GreB on transcription initiation: insights into the mechanisms of factors that bind in the secondary channel of RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 3661243-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutherford, S. T., C. L. Villers, J.-H. Lee, W. Ross, and R. L. Gourse. 2009. Allosteric control of Escherichia coli rRNA promoter complexes by DksA. Genes Dev. 23236-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma, A. K., and S. M. Payne. 2006. Induction of expression of hfq by DksA is essential for Shigella flexneri virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 62469-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaychikov, E., E. Martin, L. Denissova, M. Kozlov, V. Markovtsov, M. Kashlev, H. Heumann, V. Nikiforov, A. Goldfarb, and A. Mustaev. 1996. Mapping of catalytic residues in the RNA polymerase active center. Science 273107-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]