Abstract

Many pathogenic gram-positive bacteria release exotoxins that belong to the family of cholesterol-dependent cytolysins. Here, we report that human α-defensins HNP-1 to HNP-3 acted in a concentration-dependent manner to protect human red blood cells from the lytic effects of three of these exotoxins: anthrolysin O (ALO), listeriolysin O, and pneumolysin. HD-5 was very effective against listeriolysin O but less effective against the other toxins. Human α-defensins HNP-4 and HD-6 and human β-defensin-1, -2, and -3 lacked protective ability. HNP-1 required intact disulfide bonds to prevent toxin-mediated hemolysis. A fully linearized analog, in which all six cysteines were replaced by aminobutyric acid (Abu) residues, showed greatly reduced binding and protection. A partially unfolded HNP-1 analog, in which only cysteines 9 and 29 were replaced by Abu residues, showed intact ALO binding but was 10-fold less potent in preventing hemolysis. Surface plasmon resonance assays revealed that HNP-1 to HNP-3 bound all three toxins at multiple sites and also that solution-phase HNP molecules could bind immobilized HNP molecules. Defensin concentrations that inhibited hemolysis by ALO and listeriolysin did not prevent these toxins from binding either to red blood cells or to cholesterol. Others have shown that HNP-1 to HNP-3 inhibit lethal toxin of Bacillus anthracis, toxin B of Clostridium difficile, diphtheria toxin, and exotoxin A of Pseudomonas aeruginosa; however, this is the first time these defensins have been shown to inhibit pore-forming toxins. An “ABCDE mechanism” that can account for the ability of HNP-1 to HNP-3 to inhibit so many different exotoxins is proposed.

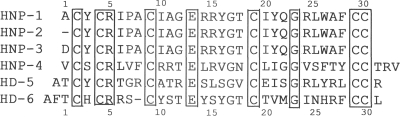

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) contain three α-defensin peptides, called HNP-1, -2, and -3 (18, 59). They have almost identical sequences (XCYCRIPACIAGERRYGTCIYQGRLWAFCC), where “X” is alanine in HNP-1, aspartic acid in HNP-3, and absent in HNP-2. Collectively, HNP-1 to HNP-3 comprise 30 to 50% of total protein in a human PMN's primary (“azurophil”) granules and 5 to 7% of the cell's total protein (60). The concentration of HNP-1 to HNP-3 in azurophil granules approximates 50 mg/ml, ensuring that a PMN's phagocytic vacuoles also contain high HNP concentrations (17). Human PMNs have small amounts of one additional α-defensin, HNP-4 (69), whose sequence differs substantially from HNP-1 to HNP-3 (Fig. 1; Table 1). The other human α-defensins, HD-5 and HD-6, are primarily expressed in small intestinal Paneth cells and are believed to protect the intestinal tract against food- and waterborne pathogens, to modulate the intestinal flora, and to be key factors in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease in genetically susceptible humans (3, 67). Although the studies described below focused on human α-defensins, some studies also examined human β-defensin peptides hBD-1, hBD-2, and hBD-3. hBD-1 is expressed constitutively by epithelial cells and keratinocytes throughout the body (76). hBD-2 and hBD-3, which are typically inducible, are also widely expressed. hBD-3 differs from the other α- and β-defensins studied here in two important respects, as follows: its exceptionally high cationicity (net charge, +11) and the relative salt insensitivity of its antimicrobial activity (25, 49).

FIG. 1.

The sequences of six human α-defensins are shown, with their conserved residues boxed.

TABLE 1.

Properties of cytolysins used in this studya

| Cytolysin | Mass (kDa) | No. of residues (total no. of residues/no. of acidic residues) | pI | % Amino acid identity (% amino acid similarity) of cytolysins to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALO | LLO | PLY | ||||

| ALO | 51.6 | 466/53 | 5.91 | 100 | 41 (64) | 42 (66) |

| LLO | 52.7 | 473/55 | 6.18 | 41 (64) | 100 | 43 (66) |

| PLY | 52.8 | 470/66 | 5.14 | 42 (66) | 43 (66) | 100 |

The sequences of six human α-defensins are shown in Fig. 1

In addition to their antimicrobial, antiviral, and immunoenhancing properties (4, 37, 60), HNP-1 to HNP-3 can inactivate multiple bacterial exotoxins, including anthrax lethal factor (34), diphtheria toxin (36), exotoxin A of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (36), and toxin B of Clostridium difficile (21). Each of these exotoxins is an enzyme. Anthrax lethal factor is a zinc-dependent metalloprotease (14), diphtheria toxin (7) and exotoxin A (10) mediate ADP-ribosylation, and C. difficile toxin B glucosylates small, GTP-binding proteins (21).

This study examined the ability of defensins to inactivate three homologous cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) (22, 64), anthrolysin O (ALO) from Bacillus anthracis (42, 61), listeriolysin O (LLO) from Listeria monocytogenes (1, 50), and pneumolysin (PLY) from Streptococcus pneumoniae (28, 53). These exotoxins lack enzymatic activity and function by initially binding cell membrane cholesterol and then undergoing orderly oligomerization and conformational changes that lead to the formation of very large transmembrane pores (23, 64, 65). LLO, a major virulence determinant of L. monocytogenes, enables ingested bacteria to escape a macrophage's phagosome and enter its cytoplasm (50). ALO can be substituted for LLO in this activity (68). PLY contributes to virulence early in pneumococcal pneumonia (52, 53) and is a promising vaccine candidate. The contribution of ALO to the pathogenesis of anthrax infection is uncertain; however, ALO is immunogenic (12), and antibody passively administered to ALO protects mice challenged by an otherwise lethal dose of B. anthracis strain Sterne (43).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cytotoxins.

Recombinant LLO was purchased from bio-WORLD (Dublin, OH). We used a pTrcHis expression vector provided by Rodney Tweten of the University of Oklahoma to prepare recombinant ALO with a six-histidine tag. This ALO was purified from 4× 500 ml cultures of Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) grown in “terrific broth” (Fisher) supplemented with 4 g/liter glycerol. ALO expression was induced by adding 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) when the cultures reached an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 to 1.2. After an additional 4-hour incubation at 37°C, the bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in 40 ml of binding buffer (500 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, 20 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.4]), and lysed by one passage through a French press at 15,000 lb/in2. After the lysate was cleared by centrifugation, it was loaded onto a 1-ml HiTrap chelating HP column (Amersham) that was washed with binding buffer and eluted with a linear gradient of imidazole in binding buffer. Fractions containing ALO were pooled and concentrated to 4 mg/ml, followed by endotoxin removal using Detoxi-Gel, per the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Recombinant ALO, domain 4, contained residues 403 to 512 of the holotoxin (GenPept accession no. YP_029366) and was prepared as previously described (11). Recombinant ALO lacking domain 4 (E35-Y402) but containing domains 1 to 3 was produced by amplification of B. anthracis 7702 chromosomal DNA with primer set 5′-GGTCTCCCATGGAAACACAAGCCGGT-3′ (forward) and CTCGAGCTAATATTCTGTAGTTGTCGTCTC-3′ (reverse) and cloned into expression vector pETHSu (K300-01; Invitrogen) using the BsaI and XhoI sites. The protein, purified as previously described (11), was passed over polymyxin B-4% agarose columns (Sigma-Aldrich) to remove endotoxin, per the manufacturer's instructions. Endotoxin was undetectable by Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Cambrex Bio Science, Walkersville, MD) in proteins eluted from the columns with 20 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2.

The coding sequence of the PLY gene was amplified by PCR with primers NdeI-Ply-up (5′-GGAATTCCATATGGCAAATAAAGCAG-3′) and Ply-down-XhoI (5′-CCGCTCGAGGTCATTTCTACCTTATC-3′), using genomic DNA of S. pneumoniae strain TIGR4 as a template. These primers added unique restriction sites (underlined) and led to amplification of the entire PLY sequence, omitting the stop codon to allow for addition of a C-terminal six-histidine tag. The product was confirmed by sequencing, digested with NdeI and XhoI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), and cloned into pET29a (EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA) cut with NdeI and XhoI. The plasmid was maintained in E. coli BL21-AI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ) and 0.02% l-arabinose (Sigma). Purification was done using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), per the manufacturer's instructions. The eluted PLY was dialyzed extensively against lipopolysaccharide-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Defensins.

Human α- and β-defensins and analogs thereof were synthesized, as described previously (70-72). Their integrity was verified by analytical reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry, and their concentrations were adjusted by absorbance at 280 nm (A280) measurements.

Hemolysis assays.

We measured CDC-mediated lysis in two ways, as follows: by a kinetic assay that provided real-time monitoring (40) and by a conventional end-point assay. Briefly, red cells from normal human blood (2.5 ml) were washed four times with PBS and suspended in PBS at 5% by volume. Defensin stock solutions, stored in 0.01% acetic acid at −20°C, were thawed and diluted into PBS before each experiment. Assays were done in 96-well plates, with a final volume of 0.1 ml/well. CDCs (25 μl) and defensins (25 μl) were added to the wells and preincubated for 15 min on ice before adding erythrocytes (RBC) (50 μl). Final CDC concentrations varied from 10 to 250 ng/ml. After all components were mixed, the plate was placed in a SpectraMax 250 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. During this time, the A700 of each well was recorded every 30 s, automatically shaking the plate before each reading. The A700 readings at 30 min were used to calculate the percent protection for the “kinetic assay,” as described below.

For “end-point” analysis, after incubation of the plates for an additional 60 min at room temperature, 200 μl of cold PBS was added to each well before transferring the contents to small, conical tubes. After these were centrifuged for 3 min at 6000 × g, 150 μl of each supernatant was removed and transferred to a fresh 96-well microplate, and its A540 was read. Supernatants from PBS-treated and Triton X-100-treated red cells were included as standards. End-point (90-min) assays were analyzed in a conventional manner. Since the kinetic assays were performed with toxin concentrations that gave complete hemolysis by 30 min, we calculated the protective effects of defensins using the following equation, in which A700C is the untreated control (PBS plus red cells), A700T is red cells plus toxin, and A700TD is red cells plus toxin and defensin: (A700TD − A700T)/(A700C − A700T) × 100 = percent protection.

Surface plasmon resonance assays.

Binding studies were performed on a Biacore 3000 instrument (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden). CDCs and bovine serum albumin (BSA; a control) were immobilized on CM5 chips by amine coupling, as described previously (66). Studies were done using HBS-EP buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% polysorbate 20) at a flow rate of 50 μl/minute. We obtained useful information by performing “molar ratio analysis,” which is based on the principle that the magnitude of the binding response, in resonance units (RU), is proportional to the total mass of the analyte bound to the biosensor surface (32, 33). In these experiments, defensins ranged in size from 0.1 to 100 μg/ml, and the maximal RU response was measured after 4 min of flow.

Briefly, molar ratio analysis takes into account the mass of the ligand immobilized on the biosensor relative to the mass of the analyte that is bound. For example, consider the binding of HNP-1 (3,442 Da) to full-length ALO (52,700 Da). Each ALO molecule immobilized on the biosensor will give a signal, in RU, that is 15.32-fold higher (15.32 = 52,700/3,442) than the signal resulting from binding of a single HNP-1 molecule. Consequently, to calculate a molar ratio (e.g., the average number of HNP-1 molecules bound per immobilized ALO molecule), one first divides the RU of ALO immobilized on the biosensor by 15.32 to obtain an adjusted RU (RUadj) and then next divides the amount of bound HNP-1 (in RU) by this RUadj. For an experiment with HNP-1 and ALO, domains 1 to 3 (mass, 40.4 kDa), the RUadj factor would be 11.71 (40,400/3,442). For an experiment with HNP-1 and ALO, domain 4 (12.3 kDa), the RUadj factor would be 3.57 (12,300/3,442). We also used surface plasmon resonance to examine the binding of HNP-1 in solution to HNP-1 immobilized on a biosensor chip. For such experiments, the RUadj equals the observed RU, since the solution-phase and immobilized HNP-1 have the same mass.

ALO-HNP complexes.

Nondenaturing (native) PAGE was done on a 4-to-20% Tris-glycine gradient gel (Novex, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), using SDS-free Tris-glycine running buffer, pH 8.6. Samples were preincubated for 15 min in Novex Tris-glycine sample buffer ± SDS. Gels were electrophoresed toward the anode for 4 h at a constant voltage (150 V), stained with Coomassie blue, destained, and photographed. SDS-PAGE was performed on 10-to-20% Tris-glycine gradient gels (Invitrogen). Samples were treated with SDS but were neither boiled nor reduced. The gels were electrophoresed for 90 min at a constant voltage (125 V), stained with Coomassie blue, destained, and photographed.

ELISAs.

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against full-length, recombinant ALO (48) or LLO (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were used as primary antibodies. Affinity-purified, horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) was the secondary antibody. Cholesterol-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were done in 96-well flat-bottom plates (Costar; Corning, Inc., NY). Wells were coated by applying 30 μl of ethanol containing 12 μg/ml of cholesterol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). After the ethanol evaporated under mild heating applied by a hair dryer, the wells were rinsed three times with a washing buffer containing 0.9% NaCl and 0.01% Tween 20, pH 7.4. Thereafter, the wells were treated overnight at 4°C with a blocking buffer containing 2.5% BSA (fraction V) in 0.8% NaCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 5 mM KH2PO4, and 2.5 mM KCl, pH 7.4. Before use, the wells were rinsed four times with the washing buffer.

Assay samples were prepared in blocking buffer supplemented with 0.01% Tween 20. After samples (100 μl/well) had incubated for 60 min at room temperature, the wells were washed four times with 200 μl of washing buffer. Suitably diluted primary antibody, 100 μl/well, was added for 60 min at room temperature, and the wells were washed four times again, as done previously. After addition of the secondary antibody, wells were incubated for 60 min at room temperature in the dark, then washed six times with washing buffer, and incubated in the dark with 100 μl/well of tetramethylbenzidine solution (TMB single solution; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The reaction was monitored at an optical density at 650 nm for 30 min on a SpectraMax 250 microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), with readings obtained every 20 s.

With some ELISAs, wells were coated with glycophorin A (GpA) by incubating the wells overnight at 4°C with 500 ng of GpA (type MN; Sigma) in buffer (0.8% NaCl, 0.41% Na2HPO4, 0.20% KH2PO4, 0.02% KCl [pH 7.4]). Subsequent blocking, rinsing, and incubation steps were performed, as described above. To determine if bound HNP-1 interfered with the ability of the antitoxin antibodies to recognize their respective toxins, a 96-well flat-bottom plate was coated with 25 ng per well of ALO or LLO. After the wells were washed, they were blocked with 2.5% BSA at 4°C overnight, washed again, and then treated with 100 μl of solution containing 0 to 200 μg HNP-1/ml for 1 h at room temperature.

Binding of ALO and LLO to RBC.

Following appropriate institutional approval, 5 to 10 ml of blood was withdrawn from each healthy human volunteer into a Vacutainer containing EDTA (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The blood samples were washed four times with cold PBS, and the cells were resuspended in PBS at 5% (vol/vol). Solutions containing 0, 20, and 40 μg of HNP-1/ml in PBS were kept on ice. The toxins, at 1 μg/ml, were prepared in binding buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20 and were also kept on ice. Equal volumes of toxin and HNP-1 were mixed and incubated for 5 min on ice. Then, 2 volumes of washed red blood cells were added and the incubation was continued for an additional 15 min on ice. Finally, the mixtures were centrifuged to pellet the red cells. No lysis occurred under these conditions. Supernatants were mixed with an equal volume of binding buffer-0.1% Tween 20, and their toxin concentrations were measured in the cholesterol-capture ELISA. Samples containing toxin and defensins that were incubated without red blood cells were included as controls.

Effect of cholesterol on ALO-mediated hemolysis.

Pegylated cholesterol [poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyl), alpha-(3beta)-cholest-5-en-3-yl-omega-hydroxy], with a molecular weight of 5,000, was purchased from the NOF America Corporation, White Plains, NY. Assays were done in PBS, pH 7.4, using 96-well microplates. All assay components other than RBC were preincubated with ALO for 15 min before adding the RBC. Hemolysis was monitored every 30 s at 700 nm at room temperature.

RESULTS

Characterization of the CDCs.

Table 1 shows selected properties of the toxins examined in this study. Cytolysin purity was assessed by running SDS-PAGE gels loaded with 3 μg toxin/lane. After being stained with Coomassie blue, LLO and PLY showed a single band at approximately 50 to 55 kDa, with or without reduction by dithiothreitol. The ALO holotoxin showed two major bands (monomer and dimer), with apparent masses of 50 and 100 kDa, plus several faint bands representing higher-order oligomers. After reduction with dithiothreitol, the ALO holotoxin showed a single band of ∼50 kDa. Recombinant ΑLO, lacking domain 4 and containing only domains 1 to 3, showed major bands of ∼40 and 80 kDa. Recombinant ALO, domain 4, ran as a single band of ∼12 kDa (data not shown). All of the toxins were used without further purification.

Effect on hemolysis.

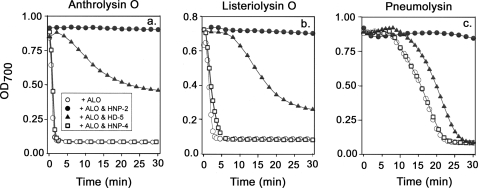

Figure 2 shows representative kinetic assays with human RBC and 250 ng/ml (∼50 nM) of each toxin and either 5 μg/ml (Fig. 2a and b) or 10 μg/ml (Fig. 2c) of defensin. Under these conditions, HNP-2 completely prevented hemolysis by all three CDCs, as did HNP-1 and HNP-3 (data not shown). HD-5 also prevented hemolysis but with lower potency than HNP-1 to HNP-3. In addition to HNP-4 (Fig. 2), HD-6 and hBD-1 to hBD-3 also lacked protective activity (data not shown). Since hBD-3 is exceptionally cationic (net charge, +11), especially relative to HNP-1 or HNP-2 (net charge, +3), defensin-mediated inhibition of hemolysis does not result simply from ionic interactions between a defensin and an anionic toxin molecule.

FIG. 2.

Effects of human defensins on CDC-mediated hemolysis in kinetic assays. The symbols are identified in panel a. Each toxin was tested at 250 ng/ml. Defensins were tested at 5 μg/ml (a and b) and at 10 μg/ml (c). OD700, optical density at 700 nm.

Table 2 compares the abilities of five human α-defensins to inhibit hemolysis induced by ALO, LLO, and PLY. Two 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) are shown for each peptide, as follows: 30-min values from kinetic assays and 90-min values from classical hemoglobin release assays. The 30- and 90-min IC50s of HNP-1 to HNP-3 are similar for ALO and LLO. However, the 90-min IC50s for PLY are two- to threefold higher than the 30-min values, showing that HNP-1 to HNP-3 retarded rather than eliminated PLY-mediated hemolysis. HD-5, an intestinal α-defensin, protected against LLO-mediated hemolysis, with mean IC50s of 2.43 μg/ml (677 nM) at 30 min and 5.44 μg/ml (1.52 μM) at 90 min. HD-5 was much less effective against ALO and was ineffective against PLY.

TABLE 2.

Ability of α-defensins to inhibit hemolysis by ALO, LLO, and PLY

| α-Defensin | Inhibition (IC50) results of hemolysis with the indicated cytolysinc

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALO

|

LLO

|

PLY

|

||||

| 30 min | 90 min | 30 min | 90 min | 30 min | 90 min | |

| HNP-1 | 2.56 ± 0.61 | 2.58 ± 0.59 | 1.12 ± 0.21 | 2.22 ± 0.36 | 13.9 ± 1.39 | 29.2 ± 3.13 |

| HNP-2 | 1.37 ± 0.12 | 1.49 ± 0.16 | 0.87 ± 0.15 | 1.55 ± 0.27 | 7.14 ± 0.74 | 13.7 ± 1.76 |

| HNP-3 | 1.63 ± 0.17 | 1.66 ± 0.21 | 0.57 ± 0.08 | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 8.90 ± 0.23 | 23.4 ± 2.77 |

| HNP-4 | ≫100a | ≫100a | 90.4 ± 5.13 | >100b | ≫100a | ≫100a |

| HD-5 | 17.7 ± 2.02 | 28.4 ± 4.14 | 2.43 ± 0.25 | 5.44 ± 0.44 | >100b | ≫100a |

No protection, even at 100 μg/ml.

A total of 100 μg/ml of HNP-4 and HD-5 reduced hemolysis by 32.8% ± 6.4% and 26.9% ± 5.5%, respectively, at 90 min. We tested LLO (100 ng/ml) at pH 5.5 because it is more potent at an acidic pH (39), but HNP-1 to HNP-3 also inhibited hemolysis effectively at pH 7.4.

IC50 data are in μg/ml and represent the means ± SEM. Experiments were performed three to five times for each entry. The 30-min results were from kinetic assays, and the 90-min results are from classical, two-stage assays. The experimental conditions (toxin concentration, pH) were as follows: ALO, 10 ng/ml, pH 0.4; LLO, 100 ng/ml, pH 5.5; PLY, 250 ng/ml, pH 7.4. We used these different toxin concentrations to compensate for their different intrinsic hemolytic potencies.

HNP-2 and HNP-3 were the most-potent inhibitors of LLO in our studies. At 30 min, HNP-3 inhibited the hemolytic activity of LLO with a mean IC50 of 0.57 μg/ml (164 nM), and HNP-2 inhibited it with a mean IC50 of 0.87 μg/ml (258 nM). Their IC50s were slightly higher in the 90-min assay, with mean IC50s of 0.99 μg/ml for HNP-3 and 1.55 μg/ml for HNP-2. We did the LLO studies at pH 5.5 for several reasons. First, LLO is more active at an acidic pH (24). Second, pH 5.5 better simulates the acidic environment of a macrophage phagosome. Third, while human macrophages do not produce HNP-1 to HNP-3, they may acquire them by importation of human PMN granules (63) or by endocytosis of solution-phase HNPs.

ALO was an extremely potent hemolysin for human RBC. Under these conditions, as little as 10 ng/ml ALO caused virtually complete hemolysis within a few minutes (21). We studied ALO at various concentrations, most often at 250 ng/ml (Fig. 2) or at 10 ng/ml (Table 2). At 10 ng ALO/ml, the mean IC50s of HNP-2 and HNP-3 ranged from 1.37 to 1.66 μg/ml (406 to 476 nM), with no significant differences between the 30- or 90-min values. At 250 ng ALO/ml, IC50s for HNP-2 were slightly higher, as follows: 2.34 ± 0.31 μg/ml at 30 min and 2.31 ± 0.32 μg/ml at 90 min (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 3). The almost-identical IC50s for HNP-2 at 30 and 90 min indicated a durable inhibitory effect on hemolysis. HNP-3 had IC50s of 3.14 ± 0.37 μg/ml and 3.42 ± 0.49 μg/ml (mean ± SEM; n = 3) at 30 and 90 min, respectively, in experiments with 250 ng ALO/ml, and HNP-1 had IC50 values of 5.45 ± 1.18 μg/ml and 5.75 ± 1.10 μg/ml (mean ± SEM, n = 4) at 30 and 90 min, respectively, in these experiments. HD-5 had a considerably higher IC50, slightly above 100 μg/ml.

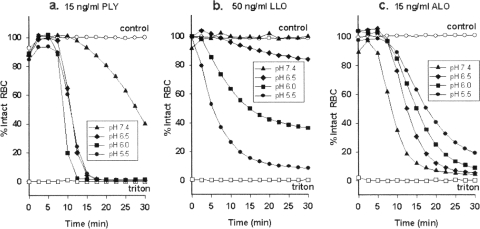

Effects of pH and serum.

Whereas the contributions of LLO to pathogenesis have been widely studied, less is known about ALO and PLY. When we determined their optimal pH for RBC lysis (Fig. 3), PLY, like LLO, functioned best in an acidic environment, suggesting that it might enable pneumococci to escape imprisonment in a macrophage's phagosome. ALO had a broad pH optimum, with peak activity at pH 7.4. The broad pH optimum of ALO could allow it to act in serum-free extracellular fluids, in the neutral pH environment of a human PMN's phagosome (8, 58), and in the more acidic phagosome of a macrophage. Addition of 10% normal human serum (data not shown) or certain cholesterol derivatives (described below) to the medium completely prevented RBC lysis by ALO. This is consistent with previous reports that the direct cytotoxic activity of ALO against human PMNs, monocytes and macrophages, and RBC is abrogated by adding free cholesterol or 10% serum (42, 61).

FIG. 3.

Optimal pH for hemolysis of human RBC. Normal human RBC were exposed to PLY (a), LLO (b), or ALO (c) at pH 7.4, 6.5, 6.0, or 5.5. Untreated control RBC (open circles) and RBC treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 (open squares) served as controls.

Binding studies.

Figure 4 compares the abilities of seven human defensins, each tested at 1 μg/ml, to bind ALO (Fig. 4a) and PLY (Fig. 4b). HNP-2 and HNP-3 bound best, followed in order by HNP-1, HD-5, hBD-3, and HNP-4. hBD-1 and hBD-2 were also tested but showed no binding. Overall, relative CDC binding and neutralization were concordant. To learn if binding was fully reversible, we extended the duration of the dissociation phase from 2 min, as shown in Fig. 4a and b, to 30 min, as shown in Fig. 4c and d. Figure 4c shows that the complex between HNP-2 and PLY or ALO dissociates much more slowly than the complex between BSA and HNP-2, indicating the far greater stability of the defensin-toxin complexes. Addition of 10 mg/ml of fetuin, an extensively glycosylated protein found in fetal bovine serum, to the dissociation buffer enhanced the dissociation rate considerably, so that by 30 min only about 10% of the HNP-2/toxin complexes remained intact. Thus, the binding of HNP-2 to CDCs is predominantly reversible, although a minor irreversible component, which might form via thiol-disulfide exchange (45), cannot be excluded.

FIG. 4.

Binding of human α- and β-defensins to immobilized ALO and PLY. (a, b) Binding of six α-defensins and one β-defensin (hBD-3) to immobilized ALO (a) and PLY (b). Each defensin was tested at 1 μg/ml. hBD-1 and hBD-2 were also tested but showed no binding to ALO or PLY. These studies were performed by surface plasmon resonance. (c) Dissociation of HNP-2 complexed to ALO, PLY, and BSA over 30 min when the flow cells are perfused with HBS-EP buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% polysorbate 20). Note that the ordinate scale is logarithmic. (d) Dissociation of HNP-2 from ALO, PLY, and LLO when the flow cells are perfused with HBS-EP buffer supplemented with 10 mg/ml fetuin.

Binding to ALO domains.

CDCs contain four domains. Domain 4 contains a conserved undecapeptide (ECTGLAWEWWR) that is present in ALO, LLO, and PLY and whose interaction with target cell membrane cholesterol precedes the formation of a trans-membrane beta-barrel pore that is formed by domain 3 (27). To determine if defensins might bind the cholesterol-binding moiety of domain 4, we synthesized a 14-residue peptide (RECTGLAWEWWRTV-amide) and immobilized it on a CM5 biosensor chip. HNP-2 bound the 14-mer in a biphasic manner. Maximal binding occurred after about 70 s and then thereafter declined by about 25% over the next 2 minutes. Thus, the maximum molar ratio achieved by 1 μg/ml of HNP-2 was 0.66, declining to 0.49 after 3 min (Table 3). If similar binding were to occur in defensin-treated CDC holotoxins, it might interfere with the ability of the CDC toxins to interact with their membrane cholesterol docking site. We will revisit this possibility later.

TABLE 3.

Binding to the cholesterol-binding domaina

| α-Defensin | ka (104/M/s) | Kd (10−3/s) | KD (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HNP-1 | 14.8 | 21.6 | 145.9 |

| HNP-2 | 17.9 | 33.7 | 188.0 |

| HNP-3 | 19.3 | 37.5 | 194.3 |

| HNP-4 | 5.22 | 59.5 | 1,140 |

| HD-5 | 26.6 | 12.6 | 47.4 |

| HD-6 | 0.17 | 15 | 8,824 |

The sequence of the immobilized, 14-residue peptide was RECTGLAWEWWRTV-amide. Its 11-residue cholesterol-binding domain is underlined. The 14-residue sequence is identical to those found in the CDCs of alveolysin from Paenibacillus alvei and ivanolysin from Listeria ivanovii. The first 13 residues are identical to those found in PLY and LLO. Abbreviations: ka, rate of association; Kd, rate of dissociation; KD, equilibrium binding constant.

Figure 5a shows binding isotherms, in RU, for 10 HNP-1 concentrations from 0.1 to 1.0 μg/ml. Its noteworthy features include clustered RU values between 0.5 and 0.9 μg HNP-1/ml and high binding signals. Figure 5b shows binding of HNP-1 to the following three ALO preparations: the 4-domain holotoxin, a truncated ALO variant lacking domain 4, and domain 4 of ALO. Binding is expressed as the molar ratio, i.e., mol of HNP-1 bound/mol of toxin. Values are the means from two experiments. At 0.8 μg HNP-1/ml, ∼4.5 defensin molecules bound each 51.6-kDa ALO holotoxin molecule; approximately three HNP-1 molecules bound to domains 1 to 3, and one HNP-1 molecule bound to domain 4. Figure 5c shows the molar binding ratios for higher HNP-1 concentrations. Molecules of ALO holotoxin exposed to 25 and 50 μg/ml of HNP-1 bound, on average, about 18 and 25 defensin molecules, respectively. Figure 5d contains the binding data from Fig. 5c and b in a log-log plot, which allows them to be shown in a single panel.

FIG. 5.

Binding of HNP-1 to ALO, ALO lacking domain 4, and domain 4 of ALO. (a, b) Binding of HNP-1 (0.1 to 1.0 μg/ml) to immobilized ALO holotoxin (a) and to ALO holotoxin (domains 1 to 4, open circles), ALO lacking domain 4 (domains 1 to 3, solid circles), and domain 4 of ALO (solid triangles) (b), each immobilized on the same CM5 biosensor. Every data point is a mean value derived from two separate experiments. HNP-1 binding to immobilized HNP-1 is depicted as open diamonds. When binding is shown as a molar ratio (molecules of HNP-1 per molecule of ALO), this value was derived from the peak RU levels at each concentration. (c) Binding (molar ratios) for higher concentrations of HNP-1. (d) Log-log plot of the data shown in panels b and c.

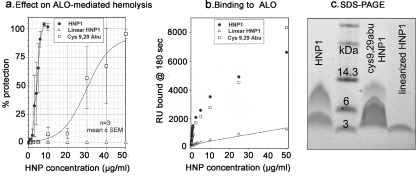

All α-defensins contain three disulfide bonds and have a characteristic disulfide pairing motif in which cysteine 1 (the amino-terminal cysteine) and cysteine 6 (the C-terminal cysteine) are paired, as are cysteines 2 and 4 and cysteines 3 and 5. To determine if these disulfide bonds were needed to allow HNP-1 to inactivate CDCs in hemolysis assays, we did the experiment illustrated in Fig. 6a. Whereas normal HNP-1 protected red blood cells from ALO with an IC50 of ∼ 3 μg/ml, the IC50 of (Cys 9,29 α-aminobutyric acid [Abu])-HNP-1, a partially linearized analog lacking only the disulfide bond between its third and fifth cysteines, was ∼30 μg/ml. A fully linearized HNP-1 analog, in which all six cysteines were replaced by Abu, showed no protective ability at 50 μg/ml, the highest concentration tested. Figure 6b shows the comparison of the binding of HNP-1 and these two disulfide analogs to immobilized ALO. The fully linearized HNP-1 analog showed greatly reduced binding to the holotoxin, but normal HNP-1 and (Cys 9,29 Abu)-HNP-1 bound the toxin equally well. Figure 6c shows how these peptides (5 μg/lane) migrated on an SDS-PAGE gel. The fully linearized HNP-1 ran exclusively as a monomer, and HNP-1 ran as a mixture of monomers and dimers, with the dimers being more abundant. In contrast, monomers were considerably more abundant in the lane containing the (Cys 9,29 Abu)-HNP-1 variant. Thus, the lack of the disulfide bond between the third and fifth cysteine residues of HNP-1 impedes the ability of solution-phase HNP-1 to dimerize.

FIG. 6.

Role of disulfide bonds in protection against hemolysis. Analogs of HNP-1 lacking one disulfide bond [(Cys 9,29 Abu)-HNP-1] or lacking all three disulfide bonds (linear HNP-1) were compared to HNP-1 for their ability to protect red cells from ALO-mediated lysis. In the linearized molecule, all six cysteines were absent. In the partially linearized (Cys 9,29 Abu)-HNP-1 variant, only the disulfide bond between the third and fifth cysteines (Cys 9 and 29) was absent. (a) The IC50 of the (Cys 9,29 Abu)-HNP-1 variant was approximately 30 μg/ml, i.e., about 10-fold higher than the IC50 of HNP-1. The linearized molecule was completely nonprotective, even at 50 μg/ml. Three experiments were performed with each peptide. Symbols show means ± SEM of percent protection. (b) Comparison of the binding of HNP-1, (Cys 9,29 Abu)-HNP-1, and linear HNP-1 to immobilized ALO holotoxin. (c) SDS-PAGE gel that was stained with Coomassie blue. One lane contains molecular mass standards (SeeBlue Plus2; Invitrogen). The other lanes each contain 5 μg of the indicated peptides.

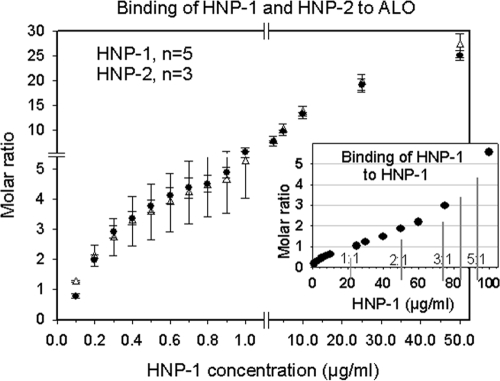

Figure 7 shows the comparison of the binding of HNP-1 and HNP-2 to ALO holotoxin and shows that they behave almost identically. At the mean IC50 for ALO of HNP-1 or HNP-2 (Fig. 1; Table 1), five to eight defensin molecules were bound to each ALO molecule, on average. The multiplicity rose to about 15 at 10 μg/ml and to about 25 at 50 μg/ml. The inset in Fig. 7 is relevant to these high defensin/toxin molar ratios. It shows that relatively minor self-association of HNP-1 occurs at concentrations up to 2.5 μg/ml. Thereafter, self-association increases progressively, reaching a 1:1 ratio at ∼20 μg/ml and a 2:1 ratio at ∼50 μg/ml. Thus, up to two-thirds of the 25 HNP-1 molecules bound to ALO exposed to 50 μg HNP-1/ml may be binding to ALO-bound defensins instead of binding directly to ALO.

FIG. 7.

Binding properties of HNP-1 and HNP-2. The main figure demonstrates that HNP-1 (solid circles) and HNP-2 (open triangles) show virtually identical binding to immobilized ALO. Symbols represent means ± SEM from five experiments with HNP-1 and three experiments with HNP-2. The inset shows the binding of HNP-1 to immobilized HNP-1, a property called self-association in this report.

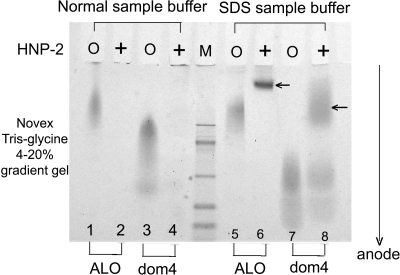

PAGE experiments.

The formation of HNP/ALO complexes was also shown by PAGE (Fig. 8). Because we used a setup that allowed samples to migrate only toward the anode, positively charged HNP-2 (net charge, +3) did not enter the gel. In contrast, ALO holotoxin (net charge, −1) and ALO, domain 4 (net charge, −2), did enter the gel and can be seen in Fig. 8, lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7. When ALO molecules bound HNP-2, the resulting complex acquired a net positive charge that prevented anodal migration and caused the cytolysins to disappear from the gel (Fig. 8, lanes 2 and 4). Addition of SDS to the sample buffer gave toxin-HNP complexes a negative charge that allowed them to migrate into the gel (Fig. 8, lanes 6 and 8).

FIG. 8.

Demonstrating the formation of ALO-HNP-1 complexes by SDS-PAGE. Electrophoresis was done on a 4 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gel. Lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6 contained 2.5 μg of ALO holotoxin, and lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8 contained 2.5 μg of ALO, domain 4. HNP-2 (2.5 μg) was added to samples in lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8 (+) but not to samples in odd-numbered lanes (O). HNP-2 is positively charged and, given the gel's polarity, would not normally enter the gel. Samples in lanes 1 to 4 were dissolved in conventional Tris-glycine sample buffer. Samples in lanes 5 to 8 were dissolved in Tris-glycine buffer containing SDS. No SDS was present in the pH 8.7 Tris-glycine running buffer. Preincubation with HNP-2 caused the disappearance of ALO (lane 2) and domain 4 (lane 4) when samples were introduced in normal sample buffer. When the sample buffer contained SDS, the complex (arrows) between ALO and HNP-2 (lane 6) and ALO, domain 4, and HNP-2 (lane 8) acquired sufficient negative charge to migrate toward the anode.

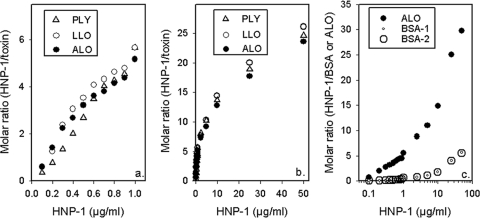

We performed additional studies to see if the binding of HNP-1 to ALO was representative of its binding to other CDCs (Fig. 9a and b). Over a 500-fold concentration range from 0.1 to 50 μg of defensin/ml, the binding of HNP-1 to ALO, LLO, and PLY was very similar. Note that, on average, each toxin molecule had bound approximately 10 HNP-1 molecules when the analyte contained 10 μg/ml of HNP-1. Figure 9c compares the binding of HNP-1 to ALO and to BSA. Although HNP-1 also bound BSA, this binding was 5- to 10-fold lower than its binding to ALO, whether expressed as molar ratios or as RU. Hence, while binding by HNP-1 is not specific, it is somewhat selective.

FIG. 9.

Comparative binding to CDCs and BSA. (a) Binding of 0.1 to 1.0 μg/ml of HNP-1 to ALO, LLO, and PLY. (b) Binding by higher HNP-1 concentrations. (c) Comparison of the binding of HNP-1 to three biosensors, one presenting ALO and two presenting BSA. All three biosensors were immobilized on the same CM5 chip to similar densities (3,022 RU for BSA-1, 3,282 RU for BSA-2, and 3,704 RU for ALO). Binding is expressed as a molar ratio (mol HNP-1/mol toxin or BSA).

Mechanistic studies.

To this point, we have shown (i) that certain human α-defensins prevent lysis of human red blood cells by CDCs (Fig. 2 and 3); (ii) that not all human defensins can do this, including α-defensins HNP-4, HD-6, and β-defensins-1 to -3 (Fig. 1; Table 1); (iii) that effective human defensins bound more extensively to CDCs than the ineffective ones (Fig. 4); (iv) that multiple molecules of HNP-1 to HNP-3 bind to a single CDC molecule (Fig. 9); and (v) that molecules of HNP-1 to HNP-3 also bind to other molecules of HNP-1 to HNP-3, including those that have bound to CDCs (Fig. 7).

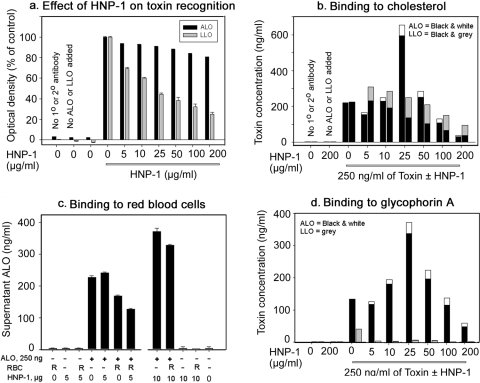

William of Ockham opined that “all other things being equal, the simplest solution tends to be the best.” Keeping this 700-year old precept (and the data in Table 3) in mind, we hypothesized that defensins interfered with the docking of CDCs to cholesterol either by binding directly to the undecapeptide cholesterol-binding motif in toxin domain 4 or by binding close enough to this cholesterol-binding site to impair its function. To test this hypothesis, we performed sensitive ELISAs, using immobilized cholesterol as the capturing reagent. Polyclonal antisera to ALO and LLO served as primary antibodies, and horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin was the secondary antibody. The assays detected <0.1 ng/100 μl of the corresponding CDC in the absence of HNP-1. Concerned that defensins might interfere with the ELISA by masking CDC epitopes recognized by the primary antibodies, we exposed ALO- or LLO-coated plates to various concentrations of HNP-1, washed them, and then added the respective primary and secondary antibodies, as per the cholesterol-capture ELISA. As expected, the ability of primary antibodies to recognize HNP-1-treated CDCs was reduced slightly for ALO and more substantially for LLO (Fig. 10a). We applied these findings to correct the results of our ELISAs.

FIG. 10.

Effect of HNP-1 on the binding properties of antibody and toxins. (a, b) Effect of HNP-1 on recognition of ALO and LLO by their cognate antibodies (a) and on binding of toxins to cholesterol (b). A total of 25 ng of ALO or LLO was added to cholesterol-capture ELISA plates ± 0 to 200 μg/ml HNP-1. Black bars show toxin concentrations, as determined by the ELISA. (a) The white (ALO) or gray (LLO) bars compensate for the effect of HNP-1 on the antibody's ability to recognize the toxins. (c) HNP-1 does not decrease the binding of ALO to red blood cells. (d) Effect of HNP-1 on binding of ALO and LLO to glycophorin A. A total of 25 ng ALO or LLO plus various concentrations of HNP-1 (0 to 200 μg/ml) were added to ELISA plates coated with glycophorin A. The black bars show toxin concentrations, as determined by the ELISA. The white (ALO) or gray (LLO) bars stacked above them compensate for the decreased ability of the antibody to recognize the toxins in the presence of HNP-1.

Figure 10b shows a cholesterol-capture ELISA that examined the ability of HNP-1 to interfere with cholesterol binding by ALO and LLO. At HNP-1 concentrations of up to 50 μg/ml, neither ALO nor LLO showed decreased binding to cholesterol. Indeed, when ALO was added in the presence of 25 μg HNP-1/ml, the amount of ALO detected by the ELISA was threefold higher than in its absence. Consistent with this finding, neither 5 μg/ml of HNP-1 nor 10 μg/ml of HNP-1 prevented the binding of ALO to red blood cells (Fig. 10c), although both HNP-1 concentrations completely prevented ALO-mediated hemolysis. These results suggested either that RBC contained CDC-binding sites other than cholesterol or that defensins could affix CDCs to other components of the red cell surface. Both of these possibilities proved to be correct.

Figure 10d shows results from an ELISA using GpA, instead of cholesterol, as the capture reagent. GpA, an abundant (106 copies/cell) and extensively glycosylated surface protein of human RBC, captured ALO ∼60% as well as cholesterol did. LLO also bound GpA but to a lesser extent. A mixture of ALO with 25 μg HNP-1/ml resulted in an increase of threefold in ALO capture, similar to our finding with cholesterol-coated plates (Fig. 10b). The twice-noted binding increases of threefold were likely caused by the binding of CDC-HNP complexes containing multiple ALO and defensin molecules. In other experiments, washed red blood cells (2.5%, vol/vol) in PBS were incubated for 30 min to 4 h at 0°C with ALO (3 to 250 ng/ml), HNP-2 (100 μg/ml), or ALO (3 to 250 μg/ml) plus 100 μg/ml of HNP-2. When examined directly or by microscopy, no evidence of aggregation or clumping was found.

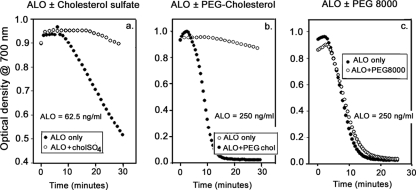

We used red blood cell targets in our experiments with LLO, PLY, and ALO, even though the bacteria that produce these pore-forming toxins form nonhemolytic colonies on blood agar plates and do not cause significant hemolysis in vivo. While we could reasonably attribute both behaviors to the protective effects of serum, we began to wonder why serum was protective. Since 1 ml of normal serum contains about 2 mg/ml of total cholesterol, we speculated that serum cholesterol could be responsible for preventing CDC-mediated hemolysis. However, the minuscule solubility of free cholesterol in aqueous media made it difficult to test this hypothesis directly. Accordingly, we turned to more-soluble analogs of cholesterol, cholesterol sulfate, and pegylated cholesterol to test this notion. Figure 11a shows that cholesterol sulfate, which is slightly soluble, can inhibit ALO-mediated hemolysis. Figure 11b shows that 250 μg/ml of the highly soluble pegylated cholesterol (corresponding to ∼19.3 μg/ml of cholesterol and 231.7 μg/ml of polyethylene glycol [PEG]) was highly protective. The same PEG-cholesterol construct was only slightly protective at 100 μg/ml and afforded no protection at 50 μg/ml (data not shown). To verify that the cholesterol moiety of PEG cholesterol was responsible for the effect shown in Fig. 11b, we tested 1-mg/ml concentrations of cholesterol-free PEG preparations with molecular weights of 8,000 (Fig. 11c) or 3,350 (data not shown) and found that neither provided any protection.

FIG. 11.

Effect of cholesterol on ALO-mediated hemolysis. (a) Cholesterol sulfate (nominal final concentration, 50 μg/ml) inhibited hemolysis induced by 62.5 ng/ml of ALO. (b) Pegylated cholesterol (PEG-cholesterol), at a final concentration of 250 μg/ml, inhibited hemolysis induced by 250 ng/ml of ALO. (c) PEG (1 mg/ml), with a molecular mass of approximately 8,000 Da (PEG 8000), did not prevent ALO-mediated hemolysis.

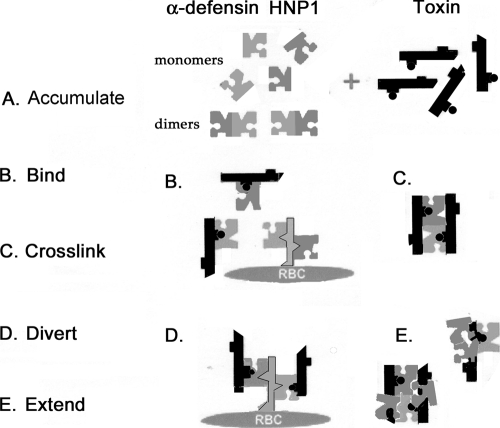

Figure 12 illustrates the ABCDE mechanism, which is our view of HNP-mediated toxin inactivation. In the cartoon representation, defensin molecules are portrayed as jigsaw puzzle pieces to show their ability to form dimers and to bind other molecules. As shown in Fig. 4 to 6, when defensins accumulate (Fig. 12A) to concentrations beyond those found in normal serum, they can bind (Fig. 12B) toxin molecules and cross-link (Fig. 12C) them by virtue of their ability to dimerize and form higher-order multimers (shown in Fig. 7). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 10, adhering toxins to “irrelevant” molecules, such as GpA, diverts (Fig. 12D) the toxin molecules from its normal receptor(s). Defensin-to-defensin binding will extend (Fig. 12E) the area of the toxin's surface covered by defensins (deduced from Fig. 7) and can also cause additional cross-linking and aggregation.

FIG. 12.

ABCDE mechanism. This cartoon depiction represents α-defensins as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle that can accumulate (A) locally to bind (B) toxin oligomers or cell surface glycoproteins, such as GpA, on the surface of RBC. HNPs self-associate to form dimers, allowing them to cross-link (C) the molecules that they bind. By tethering toxins to nonproductive bystander molecules, such as GpA, they can also divert (D) the toxins from their preferred surface receptors. Self-association—the defensin-to-defensin binding shown in the Fig. 7 inset—extends (E) the space they occupy on the surface of the toxin and can further sterically hinder the orderly toxin oligomerization required to form a pore.

DISCUSSION

The experiments described above add CDCs to the list of bacterial exotoxins inhibited by human α-defensins, which already includes anthrax lethal factor and lethal toxin (34), exotoxin A of P. aeruginosa, diphtheria toxin (36), and toxin B of C. difficile (21). All toxins previously shown to be inhibited by defensins are enzymes that exert their toxic effects intracellularly after binding to the target cell and then gaining entrance to its cytoplasm. Kim et al. (34-36) concluded that HNPs were noncompetitive inhibitors of lethal factor that bound to a region remote from its active center (34-36) and that the inhibition of diphtheria toxin and exotoxin A by HNPs was competitive against elongation factor 2 and uncompetitive against NAD+, the ADP-ribose donor (36). Uncompetitive inhibition implies that the inhibitor binds to the enzyme-substrate complex but not to the free enzyme. As CDCs lack enzymatic properties, their inhibition by defensins cannot be analyzed in this manner.

Recent studies of Clostridium difficile exotoxins provide useful counterparts to our findings with CDCs. C. difficile produces two homologous toxins, A and B. Both are large (>250 kDa), single-chain proteins whose sequences show 47% identity and 68% similarity. Early studies in animals identified toxin A as the likely agent of pseudomembranous colitis and antibiotic-associated diarrhea. However, toxin B is 100- to 1,000-fold more toxic to cultured cells than toxin A (57) and can cause similar effects in humans (38, 54, 56). Both toxins use UDP-glucose to catalyze the mono-O glycosylation of small, cytosolic GTP-binding proteins of the Rho and Ras families (reviewed in references 57 and 62), thereby disrupting functions regulating cell shape, differentiation, and proliferation. Giesemann et al. (21) reported that HNP-1 and HNP-3 inactivated C. difficile toxin B, with IC50s of 0.6 to 1.5 μM (about 2 to 5 μg/ml). HD-5 also inhibited toxin B but less potently. Importantly, they noted that high-molecular-mass aggregates, containing both toxin and HNP, formed in the presence of ≥2 μM HNP. By analyzing Coomassie blue-stained gels, they estimated that 18 pmol of toxin B coprecipitated about 250 pmol HNP-1, a molar ratio of about 14:1. HNP-1 formed similar aggregates with two B. anthracis toxins, protective antigen and lethal factor, but not with C. difficile toxin A or Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin, both of which have cytotoxic properties resistant to HNP-1.

Giesemann et al. (21) remarked that “complex formation seems to be a common feature” and that this “may represent an additional mode of action for specific defensins (e.g., HD-5) at sites where high defensin concentrations are present, for example, within specialized regions of the small intestine or phagocytic vacuoles of neutrophils.” Our data support this inference. HNP-induced complex formation and precipitation could occur by cross-linking due to dimerization (Fig. 12), which has been shown previously at the much higher HNP concentrations (29) used for nuclear magnetic resonance or X-ray crystallography studies. Aggregation of the toxin-defensin complexes might also occur by a process akin to isoelectric precipitation, since CDCs are acidic (Fig. 1; Table 1) and human defensins are modestly cationic. Thus, the binding of defensins to CDCs would cause local or global charge neutralization (Fig. 8) that might favor aggregation. In the previously reported studies, HNPs required an intact tri-disulfide structure to inactivate anthrax lethal factor, diphtheria toxin, P. aeruginosa exotoxin A, and C. difficile toxin B. This is consistent with our findings for ALO (Fig. 6).

Additional parallels exist to findings reported in studies with staphylokinase, a 136-amino-acid protein produced by lysogenic strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Staphylokinase forms a 1:1 complex with plasmin(ogen) that activates other plasminogen molecules to form plasmin, a serine protease that degrades extracellular matrix proteins. Bokarewa and Tarkowski (5) reported that HNP-1 and HNP-2 bound staphylokinase, forming complexes with a greatly reduced ability to activate plasminogen (31). As the HNP-staphylokinase complexes contained up to a sixfold molar excess of HNP-1, the authors concluded that each staphylokinase molecule contained several binding sites for HNPs. Our studies also revealed the presence of multiple binding sites for HNP-1 on CDCs (Fig. 7 and 9).

We did not examine the ability of α-defensins to neutralize CDCs in vivo but will speculate about where this would be likely to occur. Certainly, it would not occur in the circulation, because serum and plasma contain insufficient levels of α-defensins. Table 2 shows that IC50s for inhibiting ALO and LLO are higher than the concentrations of HNP-1 to HNP-3 (<100 ng/ml) found in carefully collected normal human sera (47). Even though higher HNP-1 to HNP-3 concentrations may occur in patients with severe infection (46), the presence of cholesterol may compete with the toxin's binding to its cell surface receptors. Defensin-mediated toxin neutralization is more likely to take place within the phagosomes of a PMN, at extracellular sites of inflammation, or in milieus that contain PMNs and stimuli that induce defensin secretion, such as leukotriene B4 (16, 19), the beta chemokines MIP1α, MIP1β, and RANTES (30), interleukin-8 (9), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (6). Other agents that induce the extracellular release of the azurophil granules of human PMNs include opsonized zymosan, aggregated immunoglobulin G, C5a, N-formylated peptides, and phorbol esters (2). The HNP-1 to HNP-3 content of normal neutrophils is sufficiently high that the 4 million neutrophils commonly found per milliliter of blood contain ∼20 μg of HNP-1 to HNP-3 (46).

Although human monocytes and macrophages do not express α-defensin mRNA (63), they can acquire α-defensins by ingestion of PMNs or their azurophil granules (15, 63) or by endocytosis of fluid-phase defensin (our unpublished data). Importation of fluid-phase HNP-1 and/or HD-5 was shown for human T cells (74, 75), human smooth muscle cells, and human cervical epithelial (CaSki) cells (26).

The likeliest site of action for HD-5 is the small intestine (44). Ghosh et al. reported that human terminal ileum contained 0.5 to 2.5 mg HD-5 per gram of tissue (20). Because Paneth cells secrete α-defensins in response to lipopolysaccharide (51), bacteria (55), and cholinergic stimuli (51, 55), especially high HD-5 concentrations will be present in the lumen of the intestinal crypts of Lieberkühn. Just as cervical epithelial cells can acquire HD-5 from the external milieu (26), intestinal mucosal cells might acquire extracellular defensins and use these peptides to influence the outcome of cytoplasmic or intravacuolar events.

Surface plasmon resonance allowed us to examine defensin self-association at the low micromolar concentrations commensurate with their IC50 levels for biological activities, with the caveat that one defensin molecule was immobilized by an amide bond between its N-terminal amino group and the underlying dextran matrix. We do not know if the restricted motion of the immobilized defensin would allow its solution-phase defensin partner to access the dimer interfacial surface defined by nuclear magnetic resonance and crystallography. We do know that there must be at least two ways for defensin self-association to occur or else molar ratios greater than 1:1 (Fig. 7, inset) could not occur.

The “ABCDE mechanism” shown in Fig. 12 illustrates five elements of α-defensin behavior that, in combination, allow them to inhibit CDCs. It is likely that these same elements contribute to the steadily growing list of activities attributed to α-defensins (13, 41, 73). Other factors may also contribute. To form a pore, CDCs must diffuse freely in the target cell membrane, undergo conformational changes, and assemble upwards of 60 toxin monomers (64, 65). α-Defensins might also prevent pore formation by hindering membrane diffusion, as noted previously in photobleaching experiments with retrocyclins (humanized θ-defensins) (39), or by steric hindrance of membrane fusion, which was also previously noted for retrocyclins (39). In addition, their accretion by self-association may deform the occlusal surface(s) of CDC monomers in a manner that hinders the orderly oligomerization of toxin monomers.

We can view defensins as multipurpose molecular machines, composed of mutually adapted parts (amino acids) that operate, as shown in Fig. 12, to accomplish many different kinds of work. The present study shows that certain α-defensins can inhibit CDCs, that they require an intact disulfide “skeleton” to do so, and that mere cationicity (e.g., HNP-4 or hBD-3) is insufficient to impart this property. These observations indicate that apart from the six conserved cysteines found in all α-defensins, one or more additional amino acid residues are crucial for allowing some α-defensins but not others to inhibit CDCs. Identifying such critical residues would be a valuable step in cracking the defensin “code” and furthering our understanding of the mechanism(s) of inhibition.

Editor: B. A. McCormick

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews, N. W., and D. A. Portnoy. 1994. Cytolysins from intracellular pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 2261-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentwood, B. J., and P. M. Henson. 1980. The sequential release of granule constitutents from human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 124855-862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevins, C. L. 2006. Paneth cell defensins: key effector molecules of innate immunity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34263-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biragyn, A. 2005. Defensins—non-antibiotic use for vaccine development. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 653-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bokarewa, M., and A. Tarkowski. 2004. Human alpha-defensins neutralize fibrinolytic activity exerted by staphylokinase. Thromb. Haemost. 91991-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouma, M. G., T. M. Jeunhomme, D. L. Boyle, M. A. Dentener, N. N. Voitenok, F. A. van den Wildenberg, and W. A. Buurman. 1997. Adenosine inhibits neutrophil degranulation in activated human whole blood: involvement of adenosine A2 and A3 receptors. J. Immunol. 1585400-5408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll, S. F., and R. J. Collier. 1984. NAD binding site of diphtheria toxin: identification of a residue within the nicotinamide subsite by photochemical modification with NAD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 813307-3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cech, P., and R. I. Lehrer. 1984. Phagolysosomal pH of human neutrophils. Blood 6388-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chertov, O., D. F. Michiel, L. Xu, J. M. Wang, K. Tani, W. J. Murphy, D. L. Longo, D. D. Taub, and J. J. Oppenheim. 1996. Identification of defensin-1, defensin-2, and CAP37/azurocidin as T-cell chemoattractant proteins released from interleukin-8-stimulated neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 2712935-2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung, D. W., and R. J. Collier. 1977. Enzymatically active peptide from the adenosine diphosphate-ribosylating toxin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 16832-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cocklin, S., M. Jost, N. M. Robertson, S. D. Weeks, H. W. Weber, E. Young, S. Seal, C. Zhang, E. Mosser, P. J. Loll, A. J. Saunders, R. F. Rest, and I. M. Chaiken. 2006. Real-time monitoring of the membrane-binding and insertion properties of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysin anthrolysin O from Bacillus anthracis. J. Mol. Recognit. 19354-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cowan, G. J., H. S. Atkins, L. K. Johnson, R. W. Titball, and T. J. Mitchell. 2007. Immunisation with anthrolysin O or a genetic toxoid protects against challenge with the toxin but not against Bacillus anthracis. Vaccine 257197-7205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Leeuw, E., and W. Lu. 2007. Human defensins: turning defense into offense? Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 767-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duesbery, N. S., C. P. Webb, S. H. Leppla, V. M. Gordon, K. R. Klimpel, T. D. Copeland, N. G. Ahn, M. K. Oskarsson, K. Fukasawa, K. D. Paull, and G. F. Vande Woude. 1998. Proteolytic inactivation of MAP-kinase-kinase by anthrax lethal factor. Science 280734-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estensen, R. D., M. E. Reusch, M. L. Epstein, and H. R. Hill. 1976. Role of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in some human neutrophil functions as indicated by ionophore A23187. Infect. Immun. 13146-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flamand, L., P. Borgeat, R. Lalonde, and J. Gosselin. 2004. Release of anti-HIV mediators after administration of leukotriene B4 to humans. J. Infect. Dis. 1892001-2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganz, T., M. E. Selsted, and R. I. Lehrer. 1986. Antimicrobial activity of phagocyte granule proteins. Semin. Respir. Infect. 1107-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganz, T., M. E. Selsted, D. Szklarek, S. S. Harwig, K. Daher, D. F. Bainton, and R. I. Lehrer. 1985. Defensins. Natural peptide antibiotics of human neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 761427-1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaudreault, E., and J. Gosselin. 2007. Leukotriene B4-mediated release of antimicrobial peptides against cytomegalovirus is BLT1 dependent. Viral Immunol. 20407-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh, D., E. Porter, B. Shen, S. K. Lee, D. Wilk, J. Drazba, S. P. Yadav, J. W. Crabb, T. Ganz, and C. L. Bevins. 2002. Paneth cell trypsin is the processing enzyme for human defensin-5. Nat. Immunol. 3583-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giesemann, T., G. Guttenberg, and K. Aktories. 2008. Human alpha-defensins inhibit Clostridium difficile toxin B. Gastroenterology 1342049-2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert, R. J. 2002. Pore-forming toxins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59832-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbert, R. J. 2005. Inactivation and activity of cholesterol-dependent cytolysins: what structural studies tell us. Structure (Cambridge) 131097-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glomski, I. J., M. M. Gedde, A. W. Tsang, J. A. Swanson, and D. A. Portnoy. 2002. The Listeria monocytogenes hemolysin has an acidic pH optimum to compartmentalize activity and prevent damage to infected host cells. J. Cell Biol. 1561029-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harder, J., and J. M. Schroder. 2005. Antimicrobial peptides in human skin. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 8622-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazrati, E., B. Galen, W. Lu, W. Wang, Y. Ouyang, M. J. Keller, R. I. Lehrer, and B. C. Herold. 2006. Human alpha- and beta-defensins block multiple steps in herpes simplex virus infection. J. Immunol. 1778658-8666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heuck, A. P., E. M. Hotze, R. K. Tweten, and A. E. Johnson. 2000. Mechanism of membrane insertion of a multimeric beta-barrel protein: perfringolysin O creates a pore using ordered and coupled conformational changes. Mol. Cell 61233-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirst, R. A., A. Kadioglu, C. O'Callaghan, and P. W. Andrew. 2004. The role of pneumolysin in pneumococcal pneumonia and meningitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 138195-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hristova, K., M. E. Selsted, and S. H. White. 1996. Interactions of monomeric rabbit neutrophil defensins with bilayers: comparison with dimeric human defensin HNP-2. Biochemistry 3511888-11894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jan, M. S., Y. H. Huang, B. Shieh, R. H. Teng, Y. P. Yan, Y. T. Lee, K. K. Liao, and C. Li. 2006. CC chemokines induce neutrophils to chemotaxis, degranulation, and alpha-defensin release. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 416-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin, T., M. Bokarewa, T. Foster, J. Mitchell, J. Higgins, and A. Tarkowski. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus resists human defensins by production of staphylokinase, a novel bacterial evasion mechanism. J. Immunol. 1721169-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jonsson, U., L. Fagerstam, B. Ivarsson, B. Johnsson, R. Karlsson, K. Lundh, S. Lofas, B. Persson, H. Roos, I. Ronnberg, et al. 1991. Real-time biospecific interaction analysis using surface plasmon resonance and a sensor chip technology. BioTechniques 11620-627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlsson, R. 1994. Real-time competitive kinetic analysis of interactions between low-molecular-weight ligands in solution and surface-immobilized receptors. Anal. Biochem. 221142-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim, C., N. Gajendran, H. W. Mittrucker, M. Weiwad, Y. H. Song, R. Hurwitz, M. Wilmanns, G. Fischer, and S. H. Kaufmann. 2005. Human alpha-defensins neutralize anthrax lethal toxin and protect against its fatal consequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1024830-4835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim, C., and S. H. Kaufmann. 2006. Defensin: a multifunctional molecule lives up to its versatile name. Trends Microbiol. 14428-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim, C., Z. Slavinskaya, A. R. Merrill, and S. H. Kaufmann. 2006. Human alpha-defensins neutralize toxins of the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase family. Biochem. J. 399225-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klotman, M. E., and T. L. Chang. 2006. Defensins in innate antiviral immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6447-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komatsu, M., H. Kato, M. Aihara, K. Shimakawa, M. Iwasaki, Y. Nagasaka, S. Fukuda, S. Matsuo, Y. Arakawa, M. Watanabe, and Y. Iwatani. 2003. High frequency of antibiotic-associated diarrhea due to toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile in a hospital in Japan and risk factors for infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 22525-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leikina, E., H. Delanoe-Ayari, K. Melikov, M. S. Cho, A. Chen, A. J. Waring, W. Wang, Y. Xie, J. A. Loo, R. I. Lehrer, and L. V. Chernomordik. 2005. Carbohydrate-binding molecules inhibit viral fusion and entry by crosslinking membrane glycoproteins. Nat. Immunol. 6995-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, C. C., and J. D. Young. 1988. A semi-automated microassay for complement activity. J. Immunol. Methods 11433-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menendez, A., and F. B. Brett. 2007. Defensins in the immunology of bacterial infections. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19385-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosser, E. M., and R. F. Rest. 2006. The Bacillus anthracis cholesterol-dependent cytolysin, anthrolysin O, kills human neutrophils, monocytes and macrophages. BMC Microbiol. 656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakouzi, A., J. Rivera, R. F. Rest, and A. Casadevall. 2008. Passive administration of monoclonal antibodies to anthrolysin O prolong survival in mice lethally infected with Bacillus anthracis. BMC Microbiol. 8159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ouellette, A. J. 2005. Paneth cell alpha-defensins: peptide mediators of innate immunity in the small intestine. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 27133-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panyutich, A., and T. Ganz. 1991. Activated alpha 2-macroglobulin is a principal defensin-binding protein. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 5101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panyutich, A. V., E. A. Panyutich, V. A. Krapivin, E. A. Baturevich, and T. Ganz. 1993. Plasma defensin concentrations are elevated in patients with septicemia or bacterial meningitis. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 122202-207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Panyutich, A. V., N. N. Voitenok, R. I. Lehrer, and T. Ganz. 1991. An enzyme immunoassay for human defensins. J. Immunol. Methods 141149-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park, J. M., V. H. Ng, S. Maeda, R. F. Rest, and M. Karin. 2004. Anthrolysin O and other gram-positive cytolysins are toll-like receptor 4 agonists. J. Exp. Med. 2001647-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pazgier, M., D. M. Hoover, D. Yang, W. Lu, and J. Lubkowski. 2006. Human beta-defensins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 631294-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Portnoy, D. A., V. Auerbuch, and I. J. Glomski. 2002. The cell biology of Listeria monocytogenes infection: the intersection of bacterial pathogenesis and cell-mediated immunity. J. Cell Biol. 158409-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qu, X. D., K. C. Lloyd, J. H. Walsh, and R. I. Lehrer. 1996. Secretion of type II phospholipase A2 and cryptdin by rat small intestinal Paneth cells. Infect. Immun. 645161-5165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubins, J. B., D. Charboneau, J. C. Paton, T. J. Mitchell, P. W. Andrew, and E. N. Janoff. 1995. Dual function of pneumolysin in the early pathogenesis of murine pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Clin. Investig. 95142-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rubins, J. B., and E. N. Janoff. 1998. Pneumolysin: a multifunctional pneumococcal virulence factor. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 13121-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samra, Z., S. Talmor, and J. Bahar. 2002. High prevalence of toxin A-negative toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile in hospitalized patients with gastrointestinal disease. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 43189-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Satoh, Y. 1988. Atropine inhibits the degranulation of Paneth cells in ex-germ-free mice. Cell Tissue Res. 253397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Savidge, T. C., W. H. Pan, P. Newman, M. O'brien, P. M. Anton, and C. Pothoulakis. 2003. Clostridium difficile toxin B is an inflammatory enterotoxin in human intestine. Gastroenterology 125413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schirmer, J., and K. Aktories. 2004. Large clostridial cytotoxins: cellular biology of Rho/Ras-glucosylating toxins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 167366-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Segal, A. W. 2005. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23197-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Selsted, M. E., S. S. Harwig, T. Ganz, J. W. Schilling, and R. I. Lehrer. 1985. Primary structures of three human neutrophil defensins. J. Clin. Investig. 761436-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Selsted, M. E., and A. J. Ouellette. 2005. Mammalian defensins in the antimicrobial immune response. Nat. Immunol. 6551-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shannon, J. G., C. L. Ross, T. M. Koehler, and R. F. Rest. 2003. Characterization of anthrolysin O, the Bacillus anthracis cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. Infect. Immun. 713183-3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takai, Y., T. Sasaki, and T. Matozaki. 2001. Small GTP-binding proteins. Physiol. Rev. 81153-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tan, B. H., C. Meinken, M. Bastian, H. Bruns, A. Legaspi, M. T. Ochoa, S. R. Krutzik, B. R. Bloom, T. Ganz, R. L. Modlin, and S. Stenger. 2006. Macrophages acquire neutrophil granules for antimicrobial activity against intracellular pathogens. J. Immunol. 1771864-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tweten, R. K. 2005. Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins, a family of versatile pore-forming toxins. Infect. Immun. 736199-6209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tweten, R. K., M. W. Parker, and A. E. Johnson. 2001. The cholesterol-dependent cytolysins. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 25715-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang, W., A. M. Cole, T. Hong, A. J. Waring, and R. I. Lehrer. 2003. Retrocyclin, an antiretroviral theta-defensin, is a lectin. J. Immunol. 1704708-4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wehkamp, J., G. Wang, I. Kubler, S. Nuding, A. Gregorieff, A. Schnabel, R. J. Kays, K. Fellermann, O. Burk, M. Schwab, H. Clevers, C. L. Bevins, and E. F. Stange. 2007. The Paneth cell alpha-defensin deficiency of ileal Crohn's disease is linked to Wnt/Tcf-4. J. Immunol. 1793109-3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wei, Z., P. Schnupf, M. A. Poussin, L. A. Zenewicz, H. Shen, and H. Goldfine. 2005. Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes expressing anthrolysin O and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C from Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 736639-6646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilde, C. G., J. E. Griffith, M. N. Marra, J. L. Snable, and R. W. Scott. 1989. Purification and characterization of human neutrophil peptide 4, a novel member of the defensin family. J. Biol. Chem. 26411200-11203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu, Z., B. Ericksen, K. Tucker, J. Lubkowski, and W. Lu. 2004. Synthesis and characterization of human alpha-defensins 4-6. J. Pept. Res. 64118-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu, Z., D. M. Hoover, D. Yang, C. Boulegue, F. Santamaria, J. J. Oppenheim, J. Lubkowski, and W. Lu. 2003. Engineering disulfide bridges to dissect antimicrobial and chemotactic activities of human beta-defensin 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1008880-8885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu, Z., R. Powell, and W. Lu. 2003. Productive folding of human neutrophil alpha-defensins in vitro without the pro-peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1252402-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang, D., Z. H. Liu, P. Tewary, Q. Chen, G. de la Rosa, and J. J. Oppenheim. 2007. Defensin participation in innate and adaptive immunity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 133131-3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zaharatos, G. J., T. He, P. Lopez, W. Yu, J. Yu, and L. Zhang. 2004. alpha-Defensins released into stimulated CD8+ T-cell supernatants are likely derived from residual granulocytes within the irradiated allogeneic peripheral blood mononuclear cells used as feeders. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 36993-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang, L., W. Yu, T. He, J. Yu, R. E. Caffrey, E. A. Dalmasso, S. Fu, T. Pham, J. Mei, J. J. Ho, W. Zhang, P. Lopez, and D. D. Ho. 2002. Contribution of human alpha-defensin 1, 2, and 3 to the anti-HIV-1 activity of CD8 antiviral factor. Science 298995-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao, C., I. Wang, and R. I. Lehrer. 1996. Widespread expression of beta-defensin hBD-1 in human secretory glands and epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 396319-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]