Abstract

We present the first documented case of Salmonella enterica serotype Agona meningitis in a 6-day-old baby. S. enterica serotype Agona was isolated concurrently from infant cerebrospinal fluid and parental fecal samples, and Salmonella was isolated from breast milk. The role of breast milk in transmission of Salmonella enterica is discussed.

CASE REPORT

A 6-day-old baby girl presented to the Pediatric Emergency Department with symptoms of poor feeding, grunting respiration, weight loss, and fevers. She was born at term by spontaneous vaginal delivery with a birth weight of 3.52 kg. After an uneventful observation period, mother and baby were discharged home. Two days later, her parents noticed that she was feeding poorly and had a raised temperature. She had no diarrhea or vomiting. Her general practitioner reviewed her and reassured the parents. However she deteriorated over the next few days and required hospital admission, having lost 600 g of her birth weight. On examination, she was febrile (38.3°C), her respiratory rate was 48 breaths/min, and her heart rate was 190 beats/min. She appeared pale and dehydrated, but she was responsive. She had no focal neurological signs. Her anterior fontanelle was full but not bulging. The rest of the systemic examination was unremarkable.

A diagnosis of neonatal sepsis was made, and she was started empirically on intravenous benzylpenicillin and gentamicin. The C-reactive protein was greater than 250 mg/liter (normal value, <2 mg/liter), the initial peripheral white cell count was 5.7 × 109/liter (normal at 7 days, 5 × 109 to 21 × 109/liter), and the hemoglobin level was 15.7 g/dl (normal at 7 days, 15.2 to 19.8 g/dl). Lumbar puncture revealed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that was cloudy and bloodstained with a polymorph count of 3,800 × 106/liter (normal in neonates, 0); there were no lymphocytes (normal in neonates, <20 × 106/liter) and a red blood cell count of 155,700 × 106/liter. The CSF protein concentration was greater than 2 g/liter (normal in neonates, <1 g/liter), and gram-negative bacilli were seen on Gram's stain. On the basis of these CSF findings, intravenous cefotaxime (150 mg/kg daily in three divided doses) was started. The benzylpenicillin was stopped, and the gentamicin was continued.

The baby had a complex inpatient stay, requiring intensive care admission for sepsis with respiratory distress. She received one dose of intravenous immunoglobulin for severe sepsis and required platelet support. Five days into her admission, intravenous ciprofloxacin and metronidazole were added to her cefotaxime treatment for suspected necrotizing enterocolitis. She made good progress thereafter. Repeat CSF and blood cultures were negative. After 18 days in the hospital, she was discharged home on oral ciprofloxacin to complete 4 weeks of treatment. Initial hearing assessments carried out soon after discharge were normal. Unfortunately, 12 weeks later, the baby developed postmeningitic hydrocephalus, which required insertion of a neurosurgical shunt.

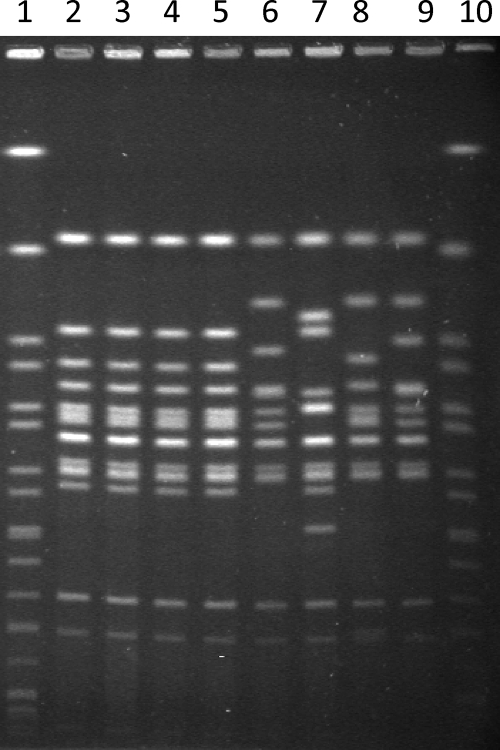

Salmonella was cultured from CSF and blood cultures taken from the baby on admission. Stool samples from both parents were tested, and Salmonella was isolated. The baby's stool samples were negative. Concurrent with the baby's hospital admission, her mother noted bilateral breast induration and tenderness, with a decline in milk production, both of which resolved after initiation of antibiotic treatment (see below). Thus, expressed breast milk samples from the mother were also tested, and three out of four separate samples taken over a 2-week period grew Salmonella species, which in two instances were mixed with coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) (Table 1). All Salmonella isolates were susceptible to amoxicillin, cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and co-trimoxazole. Four isolates (neonatal blood culture, neonatal CSF, and both parents' stool samples) were sent to the Laboratory of Gastrointestinal Pathogens at the Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections for further analysis (breast milk isolates were not available). Serotyping identified all four isolates as Salmonella enterica serotype Agona (serotype I 4,12: f,g,s:−). The resistance types (R-types) were identical, with all strains being fully sensitive, and phage typing identified them all as phage type 3 (PT3). All four isolates were indistinguishable by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), performed according to a standard protocol (11) (Fig. 1). Thus molecular typing provided strong evidence that the baby had acquired the infection from one of her parents.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the isolates from the infant and her parents

| Sample | Source individual | Date of sample (day/mo/yr) | Culture result | Characterization of S. enterica serotype Agona | PFGE resulta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF | Baby | 18/10/08 | S. enterica serotype Agona | Biotype I antigenic structure; 4,12:f,g,s:−; PT3; R-type, drug sensitive | SAGOXB.0076 (Fig. 1, lane 2) |

| 28/10/08 | Negative | ||||

| Blood cultures | Baby | 18/10/08 | S. enterica serotype Agona | Biotype I antigenic structure; 4,12:f,g,s:−; PT3; R-type, drug sensitive | SAGOXB.0076 (Fig. 1, lane 5) |

| 23/10/08, 25/10/08 | Negative | ||||

| Stool | Baby | 20/10/08, 20/12/08, 13/12/08 | Negative | ||

| Mother | 22/10/08 | S. enterica serotype Agona | Biotype I antigenic structure; 4,12:f,g,s:−; PT3; R-type, drug sensitive | SAGOXB.0076 (Fig. 1, lane 4) | |

| 13/11/08, 21/11/08, 27/11/08, 04/12/08, 12/12/08 | Negative | ||||

| Father | 22/10/08 | S. enterica serotype Agona | Biotype I antigenic structure; 4,12:f,g,s:−; PT3; R-type, drug sensitive | SAGOXB.0076 (Fig. 1, lane 3) | |

| 12/11/08, 20/11/08, 27/11/08, 04/12/08, 11/12/08 | Negative | ||||

| Urine | Baby | 18/10/08 | Non-lactose fermenter | ||

| Breast milk | Mother | 23/10/08, 29/10/08 | Salmonella species + CoNS | ||

| 30/10/08 | Salmonella species | ||||

| 06/11/08 | CoNS | ||||

| 13/11/08, 20/11/08, 27/11/08, 11/12/08 | Negative |

The nomenclature of the Salmonella PFGE patterns used by the Laboratory of Gastrointestinal Pathogens is consistent with Salm-gene/Pulse-Net. Uppercase letters are based on the serotype examined and the macrorestriction enzyme used, followed by a period and then an arbitrary number (usually based on the order in which the patterns are identified).

FIG. 1.

PFGE of S. enterica serotype Agona isolates. The infant's CSF isolate (lane 2), the parents' fecal isolates (lanes 3 and 4), and the infant's blood isolate (lane 5) show identical band patterns following electrophoresis of genomic DNA digested with XbaI. Lanes 6 to 9 are examples of other strains of S. enterica serotype Agona PT3. The molecular weight standard for S. enterica serotype Braenderup H9812 is in lanes 1 and 10 (7). Electrophoretic conditions were as standardized by Salm-gene/PulseNet Europe (200 V for 22 h in 2.0 liters of Tris-borate-EDTA [50% dilution] running buffer at 14°C with a ramp of 2 to 64 s) (11).

Neither parent had a recent history of diarrheal illness or feeling unwell. Both recalled having an episode of severe gastroenteritis 5 years previously, after eating food from a United Kingdom takeout restaurant. Both parents received eradication treatment with ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily after discussions with infectious diseases specialists, microbiologists, and Public Health doctors. Subsequent stool samples from both parents and breast milk samples from the mother were negative (Table 1). The mother completed 4 weeks of treatment, while the father stopped treatment after two weeks because of concerns about side effects. In total, each parent had five negative stool samples in the month after treatment was commenced. The mother had three further negative stool samples at the end of her course of ciprofloxacin. Although the baby was initially breast-fed, this was discontinued soon after admission and for several weeks after discharge. As the mother was keen to breast-feed, breast-feeding was restarted without complication following negative maternal stool and breast milk samples and completion of eradication treatment.

The advantages of breast-feeding include protection against infections, particularly gastroenteritis, otitis media, and upper respiratory tract infections. This is achieved through specific immunological factors (antibodies, T cells, and B cells) and more general nonspecific factors (complement, lactoferrin, properdin, and glycoconjugates) (8). However, it is well recognized that occasionally breast milk can act as the vehicle of transmission of some bacteria and viruses to the infant. Neonatal bacterial infections documented as being linked to breast milk include Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Serratia marcescens, Listeria monocytogenes, Klebsiella spp., Salmonella enterica, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Brucella melitensis, Coxiella burnetii, and group B Streptococcus (8, 12). Thus, screening programs have been developed for breast milk banks, and breast-feeding is contraindicated in specific maternal infections such as active tuberculosis (8).

Expressed breast milk frequently contains CoNS, diphtheroids, and alpha-hemolytic streptococci. These represent normal skin flora and colonize the mammary ducts. They do not cause problems to the infants, as long as the breast milk is correctly stored so the mean bacterial count remains low. Outbreaks of infections such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus spp., E. coli, and S. enterica have chiefly occurred when expressed milk has not been correctly handled or stored.

In the case described above, four samples of breast milk were analyzed over a 2-week period. The breast milk was stored in sterile, screw-top containers at 4°C for use within 24 h or frozen at −20°C for use at a later date. S. enterica was isolated alone from one sample, in conjunction with CoNS from two samples, and the fourth sample yielded only CoNS. Unfortunately there were no further samples available for culture: thus, we were not able to perform sequential quantification of bacterial concentrations, which may have confirmed a temporal relationship with acquisition of infection. The mother states that she collected the samples under aseptic conditions, and the breast milk pumps were disinfected with hypochlorite before use. It is unclear how long the parents had been asymptomatically excreting Salmonella, as they only recalled an episode of gastroenteritis 5 years previously. There was no relevant travel history, there were no occupational risks, and their general health was normal. Five years would be an unusually long period of asymptomatic carriage. A review of 32 studies describing 2,814 patients, all with nontyphoidal Salmonella infections, found the median duration of excretion to be ∼5 weeks and that persistent carriage for over 1 year occurred in <1% of cases (2).

There are several possible routes of transmission of S. enterica serotype Agona from the parents to the baby, and the precise role of breast milk remains unproven. S. enterica was cultured repeatedly from the maternal breast milk, but it is unclear if the baby acquired the infection primarily from the breast milk (which had already been infected through hematogenous or lymphatic spread within the mother) or the baby acquired the organism through an alternative route and then infected the breasts through suckling. As the mother was systemically well and afebrile, but recalled bilateral breast tenderness and a fall in milk production when the baby was admitted to hospital, it is proposed that infection of maternal breast milk most likely occurred during breast feeding, due to local contamination. Alternative routes of acquisition by the baby include from perineal contamination at the time of delivery or via the fecal-oral route from either parent, presumably via transient hand carriage. It is unusual for both parents to be asymptomatic carriers and unclear whether this was related to their severe episodes of gastroenteritis 5 years previously.

There are five published cases of neonatal salmonella infection, probably due to acquisition from breast milk, and three reported outbreaks (Table 2). In one published case, the mother reported a concurrent systemic illness (4), and there was an additional report of neonatal Salmonella infection associated with mastitis (6). One of the most compelling reports of Salmonella transmission through breast milk involved quantification of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 in sequential breast milk samples by real-time PCR (12). The rise and fall in concentration of the organism were consistent with an infectious course (i.e., colonization, pathogen growth, and immune response), rather than sporadic external contamination of milk or breast-pump machines. There was a plausible temporal relationship between breast milk concentration and neonatal infections, in that the Salmonella breast milk concentration peaked on days 13 to 15 postdelivery, and the twin infants became unwell on days 16 and 19. This coincides with the characteristic 2- to 3-day incubation period for Salmonella infections. In this published case (12), the mother was asymptomatic throughout the entire period. One proposed explanation was that the initial route of entry into the breast was via the skin, which then led to colonization of the mammary ducts. An alternative hypothesis proposed by Qutaishat was the involvement of macrophages in the priming of Salmonella organisms into the mammary gland, after gastrointestinal ingestion (12). Lactogenic hormones are involved in regulating selective homing procedures, which result in high abundance of immune cells in breast milk during lactation.

TABLE 2.

Published cases of neonatal infection with S. enterica associated with breast milk

| Serotype | No. of babies infected in outbreak | Outbreak transmission details | Individual case detail(s) for:

|

Source or reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant(s) | Mother | ||||

| Typhimurium | Single case | 5 | |||

| Kottbus | 7/22 infants infected | Donor was asymptomatic; transmission possibly due to improper handling or storage of milk | 14 | ||

| Kottbus | 4/7 | Donor was asymptomatic; route of transmission uncertain | 1 (outbreak 1) | ||

| Typhimurium (nonstandardizable) | 11 neonates | All neonates infected received pooled breast milk | Gastroenteritis | 4 | |

| Virchow | 4-mo-old girl exclusively breast-fed | Maternal mastitis | 6 | ||

| Senftenberg | 3-mo-old exclusively breast-fed | Asymptomatic | 13 | ||

| Typhimurium DT104 | Twins | 12 | |||

| Panama | 13-day-old exclusively breast-fed | Asymptomatic | 3 | ||

| Agona | 6-day-old, meningitis | Mastitis | This study | ||

There are three published reports of outbreaks of Salmonella infections on neonatal units (Table 2). An epidemic of Salmonella Typhimurium in Czechoslovakia in 1989 affected 11 neonates who all received mixed breast milk pooled from many mothers (4). One mother was positive for S. Typhimurium in breast milk (taken under strict aseptic conditions) and stool and gave a history of a short febrile illness (“one loose stool and temperature lasting a few hours”). She was also reported to have a positive serology test. One environmental sample (details not provided) was also positive (4). The second and third outbreaks involved S. enterica serotype Kottbus. One of these affected 7 of 22 infants in a neonatal intensive care unit in the United States in the 1970s. A case-control investigation identified the only risk factor as consumption of milk from a single donor, whose milk was subsequently found to be contaminated with Salmonella Kottbus. The donor had no evidence of gastrointestinal infection or mastitis, and it was hypothesized that improper handling and storage of the milk enabled the salmonellae to multiply to a number sufficient to cause disease (14).

There are several reports of individual cases of neonatal Salmonella infections possibly acquired through breast milk (Table 2). A 3-month-old baby in India, who had been exclusively breast-fed since birth, had S. enterica serotype Senftenberg isolated from blood, stool, throat, and gastric aspirate cultures. Salmonella Senftenberg with an identical antibiogram was cultured from the mother's breast milk, while all other individuals in the nursery were negative. The mother had no evidence of fever, diarrhea, or breast lesions (13). A 4-month-old baby girl from Scotland, also exclusively breast-fed since birth, had S. enterica serotype Virchow cultured from her stool. Her mother reported mastitis for 48 h, and breast milk and her stool samples grew Salmonella Virchow. It was thought that the baby acquired the infection from infected milk or, directly or indirectly, from contamination of the mother's skin. The maternal mastitis could have arisen by hematogenous spread, as in typhoid fever, but, in the absence of a febrile illness, ascending infection seemed more likely. The authors recommended that whereas breast-feeding should continue in cases of sporadic puerperal mastitis, if coincidental gastroenteritis occurs in the baby or mother, breast-feeding should be temporarily stopped until results of bacteriological investigations are available (6).

Recurrent S. enterica serotype Panama meningitis has been reported in a 13-day-old, exclusively breast-fed baby, which was thought to have been acquired through contaminated breast milk. The mother reported no symptoms of gastroenteritis or mastitis, and maternal stool and blood cultures were negative. The mother continued to excrete the organism asymptomatically for at least 2 weeks (3).

S. enterica serotype Agona is uncommonly isolated from humans in England and Wales. Between 1981 and 2004, its average incidence was 154 human cases per year, while from 2005 to 2007, its average incidence dropped to 85 per year. In 2008, there were 228 human cases, and S. enterica serotype Agona ranked as the fourth most common nontyphoidal Salmonella serotype isolated from humans in England and Wales.

S. enterica serotype Agona has been responsible for several significant food-borne outbreaks (9, 10, 15). Of interest, an outbreak of gastroenteritis due to S. enterica serotype Agona started in February 2008, affecting residents in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Finland. By August 2008, there were 119 cases internationally (77 in England and Wales), and by mid-September, there were 105 cases in England and Wales alone (Health Protection Agency, Colindale, London, United Kingdom). Molecular typing of strains from human cases and from contaminated meat products confirmed that the cases were linked to an Irish food production company and a retail outlet chain supplied by this company (10). The strain responsible was characterized as a new phage type, PT39, and by PFGE as SAGOXB.0066. This strain was distinct from the strain in this case study, which was defined by the Laboratory of Gastrointestinal Pathogens as PT3, SAGOXB.0076. Four unrelated isolates of PT3 isolated earlier in 2008 were also distinct from each other and from the strain in this study.

In conclusion, Salmonella Kottbus was initially thought to have a specific predilection to colonize the mammary glands (14). The present case and the literature review extend the list of serotypes associated with possible breast milk-acquired infection to Typhimurium (5, 12), Senftenberg (13), Panama (3), Virchow (6), and Agona (this case) (Table 2). Salmonellae may colonize the breast directly via the mother's bloodstream (possibly contained within macrophages) or indirectly via infection of the suckling neonate.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathy Bamford, Imperial College, for helpful discussions and Elizabeth DePinna, Unit Head, Salmonella Reference Laboratory, HPA, Colindale, United Kingdom.

No financial support was sought for this study. No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Parental consent for publication was obtained in writing.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. 1978. Nosocomial salmonellosis in infants associated with consumption of contaminated human milk: summary of two outbreaks. Natl. Nosocomial Infect. Study Rep. 197814-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchwald, D. S., and M. J. Blaser. 1984. A review of human salmonellosis. II. Duration of excretion following infection with nontyphi Salmonella. Rev. Infect. Dis. 6345-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, T.-L., P.-F. Thien, S.-C. Liaw, C.-P. Fung, and L. K. Siu. 2005. First report of Salmonella enterica serotype Panama meningitis associated with consumption of contaminated breast milk by a neonate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 435400-5402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drhova, A., V. Dobiasova, and M. Stefkovicova. 1990. Mother's milk—unusual factor of infection transmission in a salmonellosis epidemic on a newborn ward. J. Hyg. Epidemiol. Microbiol. Immunol. 34353-355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischrocker, G., C. Vutuc, and H. P. Werner. 1972. Infection of a newborn infant by breast milk containing Salmonella typhimurium. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 84394-395. (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibb, A. P., and P. D. Welsby. 1983. Infantile salmonella gastroenteritis in association with maternal mastitis. J. Infect. 6193-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter, S. B., P. Vauterin, M. A. Lambert-Fair, M. S. Van Duyne, K. Kubota, L. Graves, D. Wrigley, T. Barrett, and E. Ribot. 2005. Establishment of a universal size standard strain for use with the PulseNet standardized pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols: converting the national databases to the new size standard. J. Clin. Microbiol. 431045-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones, C. A. 2001. Maternal transmission of infectious pathogens in breast milk. J. Paediatr. Child Health 37576-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Killalea, D., L. R. Ward, D. Roberts, J. de Louvois, F. Sufi, J. M. Stuart, P. G. Wall, M. Susman, M. Schwieger, P. J. Sanderson, I. S. Fisher, P. S. Mead, O. N. Gill, C. L. Bartlett, and B. Rowe. 1996. International epidemiological and microbiological study of outbreak of Salmonella agona infection from a ready to eat savoury snack. I. England and Wales and the United States. Br. Med. J. 3131105-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Flanagan, D., M. Cormican, P. McKeown, N. Nicolay, J. Cowden, B. Mason, D. Morgan, C. Lane, N. Irvine, and L. Browning. 14 August 2008, posting date. A multi-country outbreak of Salmonella Agona, February-August 2008. Euro Surveill. 1318956. http://www.eurosurveillance.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters, T. M., C. Maguire, E. J. Threlfall, I. S. Fisher, N. Gill, and A. J. Gatto. 2003. The Salm-gene project—a European collaboration for DNA fingerprinting for food-related Salmonellosis. Euro Surveill. 846-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qutaishat, S. S., M. E. Stemper, S. K. Spencer, M. A. Borchardt, J. C. Opitz, T. A. Monson, J. L. Anderson, and J. L. Ellingson. 2003. Transmission of Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium DT104 to infants through mother's breast milk. Pediatrics 1111442-1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revathi, G., R. Mahajan, M. M. Faridi, A. Kumar, and V. Talwar. 1995. Transmission of lethal Salmonella senftenberg from mother's breast-milk to her baby. Ann. Trop. Paediatr. 15159-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryder, R. W., A. Crosby-Ritchie, B. McDonough, and W. J. Hall III. 1977. Human milk contaminated with Salmonella kottbus. A cause of nosocomial illness in infants. JAMA 2381533-1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Threlfall, E. J., M. D. Hampton, L. R. Ward, and B. Rowe. 1996. Application of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to an international outbreak of Salmonella agona. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2130-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]