Abstract

Norwalk virus (NV) is a prototype strain of the noroviruses (family Caliciviridae) that have emerged as major causes of acute gastroenteritis worldwide. I have developed NV replicon systems using reporter proteins such as a neomycin-resistant protein (NV replicon-bearing cells) and a green fluorescent protein (pNV-GFP) and demonstrated that these systems were excellent tools to study virus replication in cell culture. In the present study, I first performed DNA microarray analysis of the replicon-bearing cells to identify cellular factors associated with NV replication. The analysis demonstrated that genes in lipid (cholesterol) or carbohydrate metabolic pathways were significantly (P < 0.001) changed by the gene ontology analysis. Among genes in the cholesterol pathways, I found that mRNA levels of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) synthase, squalene epoxidase, and acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT), ACAT2, small heterodimer partner, and low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)-related proteins were significantly changed in the cells. I also found that the inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis using statins (an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor) significantly increased the levels of NV proteins and RNA, whereas inhibitors of ACAT significantly reduced the replication of NV in replicon-bearing cells. Up- or downregulation of virus replication with these agents significantly correlated with the mRNA level of LDLR in replicon-bearing cells. Finally, I found that the expression of LDLR promoted NV replication in trans by transfection study with pNV-GFP. I conclude that the cholesterol pathways such as LDLR expression and ACAT activity may be crucial in the replication of noroviruses in cells, which may provide potential therapeutic targets for viral infection.

Human noroviruses are now the leading cause of food- or waterborne gastroenteritis illnesses responsible for more than 60% of outbreaks (10). It has been estimated that noroviruses cause 23 million cases of illness, 50,000 hospitalizations, and 300 deaths each year in the United States alone (19). Molecular epidemiological studies have confirmed a global distribution of these viruses (13). The major public health concern with human noroviruses is their ability to cause large outbreaks in group settings such as schools, restaurants, summer camps, military units, hospitals, nursing homes, and cruise ships. Human noroviruses are currently classified as NIAID category B priority pathogens (category B bioterrorism agents). Noroviruses generally cause mild to moderate gastroenteritis, but the disease can be severe to life-threatening in the young, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients. During the last decade, noroviruses have gained media attention for causing large-scale outbreaks of gastroenteritis on cruise ships, in nursing homes, etc. Although noroviruses do not multiply in food or water, they can cause large outbreaks because as few as 10 to 100 virions are sufficient to cause illness in a healthy adult (12). Recent reports of noroviral gastroenteritis outbreaks among hurricane Katrina evacuees underscores the importance of preventive and therapeutic measures for noroviruses to promote public health (32). However, no vaccines or antivirals are currently available for the prevention or treatment of norovirus disease in humans, which is largely due to the absence of a cell culture system for human noroviruses. The recent development of replicon-bearing cells for Norwalk virus (NV) (7) has made possible the study of NV replication in cells and the discovery of antivirals. We recently demonstrated that the system provides an excellent platform for screening small molecules for antivirals (3, 7). We also reported another NV replicon system with reporter genes (green fluorescent protein [GFP] or luciferase) to study virus replication (4).

As a component of membrane structures and a precursor for the steroid hormones and bile acids, cholesterol is one of the most essential biological molecules in the body (8). Cholesterol levels are maintained by controlling both de novo synthesis (major) and dietary uptake (minor) of cholesterol (8). De novo synthesis of cholesterol is subject to complex regulatory controls by various enzymes such as 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase and acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) (1, 8, 21). The synthesis of bile acids from cholesterol is also tightly controlled and represents an important factor the cholesterol homeostasis (14, 22, 23). In the present study, I first performed DNA microarray analysis of replicon-bearing cells to identify cellular factors associated with NV replication. Analysis showed genes in lipid (cholesterol) or carbohydrate metabolic pathways were significantly (P < 0.001) changed by the gene ontology analysis. Because it has been shown that bile acids are essential for the replication of porcine enteric calicivirus (PEC) in cells (6) and important natural modulators of cholesterol pathways, I was particularly interested in potential regulation genes in the cholesterol pathways. I demonstrate here that the modulation of the cholesterol pathways via inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase or ACAT led to either up- or downregulation of the replication of NV. I also show that the expression level of low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) was positively correlated with NV replication in cells. These studies suggest that the cholesterol pathway is crucial for norovirus replication and provide potential therapeutic targets for noroviral infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and reagents.

NV replicon-bearing cells (G3 and HG23), BHK21 cells, and Vero cells were maintained in Dulbecco minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (chlorotetracycline [25 μg/ml], penicillin [250 U/ml], and streptomycin [250 μg/ml]). LLC-PK cells were maintained in Eagle minimal essential medium containing 5% FBS and antibiotics. The cell culture-adapted Cowden PEC strain (Po/SV/Cowden/1980/US) (11) was serially passaged at least 35 times in LLC-PK cells in the presence of 5% intestinal contents from uninfected gnotobiotic pigs or 100 μM glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDCA) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) in the cell culture medium (11, 24). Monoclonal antibodies to NV VP1 were purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Statins, including simvastatin and lovastatin, and ACAT inhibitors, including Cl-976, Sandoz 58-035, and YIC-C8-434, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Other inhibitors of cholesterol biosynthesis, including zaragozic acid and 6-fluoromevalonate, were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ezetimibe was obtained from Fisher Bioscience (Palatine, IL), and lipoprotein-free FBS was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Z-guggulsterone and mifepristone (RU486) were also obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

DNA microarray study.

To identify host factors associated with norovirus replication, I have performed DNA microarray analysis of replicon-bearing cells (HG23) and parental Huh-7 cells using an Affymetrix GeneChip apparatus. One- or two-day-old semiconfluent Huh-7 cells and HG23 cells grown in T-75 flasks were prepared for DNA microarray analysis. Total RNA, which was isolated by using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), was used on the DNA array. At least three independent cell cultures and RNA preparations were supplied for statistical analysis. The synthesis of cDNA, labeling, and hybridization were done by using Affymetrix reagents according to the instructions of the manufacturer. I used the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 (a whole-genome array covering 47,000 transcripts) for the DNA array. The entire process was done in the DNA array facility at Kansas State University. The genes either up- or downregulated in HG23 cells compared to Huh-7 cells were analyzed with a Student t test of three independent samples. The genes showing at least 1.5- or 2-fold difference with P < 0.05 were further analyzed. The DNA array data have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (9) and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE15520.

Treatment of statins in HG23 cells.

One-day old, 80 to 90% confluent HG23 or G3 cells were treated with various concentrations of statins (simvastatin or lovastatin) to examine their effects on the replication of NV. I also examined ezetimibe (an inhibitor of the Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1), zaragozic acid (a squalene synthase inhibitor), and 6-fluoromevalonate (a mevalonate-pyrophosphate decarboxylase inhibitor) in NV replicon-bearing cells. At the desired time points, the NV protein or genome were analyzed by Western blot analysis or quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR), respectively. The cytotoxic effects on HG23 cells by statins and other inhibitors were monitored by using a cell cytotoxicity assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) to calculate the effective maximum concentration with minimum cytotoxic effects. I also examined the effects of lipoprotein-free FBS on NV replication in replicon-bearing cells. Semiconfluent HG23 cells were incubated with 10% lipoprotein-free FBS for 24 or 48 h, and viral RNA was measured by real-time qRT-PCR.

Plasmids and transfection study.

NV-based plasmids, including pNV101, NV-GFP, pNV-RL (Renilla luciferase [RL]), pNV101ΔGDD, pNV-GFPΔGDD, or pNV-RLΔGDD (4), were used. I generated a pCI-based plasmid expressing small heterodimer partner (SHP)—pCI-SHP—after the gene was amplified from Huh-7 cells by using the primers, SHP-Nhe-F (5′-ATGCTAGCATGAGCACCAGCCAACCAG-3′) and SHP-Not-R (5′-atGCGGCCGCTCACCTGAGCAAAAGCATGTC-3′). After digestion of the amplicon with NheI and NotI (underlined in each primer), it was ligated into the pCI vector (Promega) digested with the same enzymes. To examine the role of LDLR expression in NV replication, the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-based vector expressing LDLR (pCMV6-LDLR) was purchased from OriGene (Rockville, MD). We reported the pCI-based plasmid expressing the leader of the capsid protein (LC) of feline calicivirus, pCI-LC, previously (4). All transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 using 2 μg of each plasmid per well in six-well plates. Cells, including BHK21 and Vero cells, were infected with the modified vaccinia virus (Ankara strain) expressing T7 polymerase (MVA-T7) (30), at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 1 h before transfection. Plasmid pNV101, NV-GFP, pNV-RL, pNV101ΔGDD, pNV-GFPΔGDD, or pNV-RLΔGDD was either transfected alone or cotransfected with pCI-SHP or pCMV6-LDLR to study the effects of SHP or LDLR in the replication of NV. After transfection, the replication of NV was monitored by detecting the expression of VP1 (pNV101), GFP (pNV-GFP), or RL (pNV-RL) with the various assays described below. To examine the effects of SHP or LC expression on the mRNA level of LDLR in HG23 cells, various concentrations (0.05 to 3 μg per well) of pCI-SHP or pCI-LC were transfected into 1-day-old semiconfluent HG23 cells. After 24 h of transfection, total RNA was extracted for use in real-time qRT-PCR to measure the mRNA level of LDLR. Empty pCI vector (3 μg/well) was also transfected into the cells as a control.

Treatment of ACAT inhibitors.

One-day old, 80 to 90% confluent HG23 cells were treated with various concentrations of ACAT inhibitors (Cl-976, YIC-C8-434, or Sandoz 58-035) to examine their effects on the replication of NV. I used alpha interferon as a control for the present study. At the desired time points, the NV protein or genome were analyzed by Western blot analysis or qRT-PCR, respectively. The nonspecific cytotoxic effects on HG23 cells by ACAT inhibitors were monitored by using a cell cytotoxicity assay kit. I also examined these ACAT inhibitors in the replication of hepatitis C virus (HCV) using GS4.1 HCV replicon-bearing cells according to procedures similar to those used for HG23 cells. The replication of HCV was assessed using real-time qRT-PCR as described previously (2).

NV replication assay.

NV replication in replicon-bearing cells was measured by using various assays, including Western blot analysis (protein levels) and real-time qRT-PCR (RNA genome level).

(i) Detection of NV protein.

The expression of the NV protein (NV Pol) was measured by Western blot analysis. Cell lysates were prepared after cells were treated with various compounds for 24 h, and Western blot analyses were performed with polyclonal antibody to NV polymerase as described previously (7).

(ii) Detection of NV genome.

To examine NV genome levels in the cells with various transfection treatments, real-time qRT-PCR was performed by using a One-Step Platinum qRT-PCR kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the protocol established for the analysis of genogroup 1 norovirus samples (15). The primers COG1F and COG1R and the probe RING1(a)-TP (Table 1) were used for the real-time qRT-PCR, which targeted genomic RNA (i.e., the sequence between positions 5291 and 5375) (15). As a quantity control of the cellular RNA levels, a qRT-PCR analysis for β-actin with the primers Actin-F and Actin-R and the probe Actin-P was performed as described previously (27). For the qRT-PCR, the total RNA of cells (in six-well plates) was extracted with an RNeasy kit. The qRT-PCR amplification was performed in a Cepheid SmartCycler with the following parameters: 45°C for 30 m and 95°C for 10 m, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C for 1 m, and elongation at 72°C for 30 s. The relative genome levels in cells with various transfection treatments were calculated after the RNA levels were normalized to those of β-actin.

TABLE 1.

Primers and probes used for real-time qRT-PCR detection of NV RNA and mRNA of β-actin, human SHP, human LDLR, and porcine SHP

| Primer or probe | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| Primer | |

| COG1F | CGYTGGATGCGNTTYCATGA |

| COG1R | CTTAGACGCCATCATCATTYAC |

| Actin-F | GGCATCCACGAAACTACCTT |

| Actin-R | AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG |

| H-SHP-F | TGCCCAGCATACTCAAGAAG |

| H-SHP-R | GCTCCAGAAGGACTCCAGAC |

| H-LDLR-F | GGCGACAGATGTGAAGAGAA |

| H-LDLR-R | AGAGACAAGCACGTCTCCTG |

| P-SHP-F | CCCTCTTCCTGCTTGGTTT |

| P-SHP-R | TCCTCCAGCAGGATCTTCTT |

| Probe | |

| RING1(a)-TP | FAM-AGATYGCGATCYCCTGTCCA-TAMRA |

| Actin-P | HEX-ATCATGAAGTGTGACGTGGACATCCG-TAMRA |

| H-SHP-P | FAM-CTGCCTCCACTGCTGCTGGG-TAMRA |

| H-LDLR-P | FAM-CTGGCACTCAGCGCTGCCAT-TAMRA |

| P-SHP-P | FAM-CGGCCACCTCGAAGGTCACA-TAMRA |

(iii) Expression of GFP.

After the transfection of plasmids encoding the GFP gene, GFP-positive cells were detected by fluorescence microscopy or enumerated by flow cytometry analysis. After 16 to 20 h of transfection, cells were treated with trypsin and fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 1 h and then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline by centrifugation and resuspended with phosphate-buffered saline. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a population of 10,000 cells using the FACSCalibur (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

(iv) Expression of RL.

At 20 h posttransfection, cell lysates were prepared from cells containing the plasmid encoding for the RL gene by using the Renilla luciferase assay system (Promega).

Treatment of Z-guggulsterone in PEC-infected cells.

To examine the role of SHP in the replication of PEC in LLC-PK cells, we used Z-guggulsterone, which blocks bile acid-mediated SHP expression in cells (28). I used mifepristone (an inhibitor of the glucocorticoid receptor) as a control in the present study. Confluent LLC-PK cells in six-well plates were inoculated with mock medium or PEC at an MOI of 0.5 for 1 h. After the incubation, medium (minimal essential medium with 10% FBS) containing mock medium, GCDCA (200 μM), GCDCA plus Z-guggulsterone (1 to 50 μM), or GCDCA plus mifepristone (50 μM) was replenished, and virus-infected cells were then incubated for an additional 24 and 48 h. After the plates were frozen and thawed three times, the replication of PEC in the presence of Z-guggulsterone or mifepristone was measured by a 50% tissue culture infective dose assay (5). The nonspecific cytotoxic effects in LLC-PK cells by Z-guggulsterone or mifepristone were monitored by the method described above. I also examined the effects of Z-guggulsterone on the replication of NV in replicon-bearing cells. Semiconfluent HG23 cells were treated with mock medium, Z-guggulsterone (1 to 50 μM) for 24 h, and virus replication was measured by real-time qRT-PCR as described above.

Measurement of mRNA level of SHP in LLC-PK cells or mRNA levels of SHP or LDLR in HG23 cells.

To examine the effects of bile acids on the mRNA levels of SHP in LLC-PK cells, confluent LLC-PK cells were treated with mock medium, GCDCA, GCDCA plus Z-guggulsterone, or GCDCA plus mifepristone for 24 or 48 h. The mRNA levels of SHP and LDLR in the cells were measured by real-time qRT-PCR. The primers and probes for porcine SHP and porcine LDLR are listed in Table 1, and RNA extraction and real-time qRT-PCR were performed as described above. The mRNA levels of SHP and LDLR in HG23 cells with various treatments and transfection were also measured by real-time qRT-PCR using the primers and probes for human SHP and human LDLR listed in Table 1.

Cholesterol assay.

The level of total cholesterol in the replicon-bearing cells treated with statins or ACAT inhibitors was measured by using an Amplex Red cholesterol assay kit (Invitrogen) to assess whether cholesterol levels were correlated with the replication of NV. The treatment of mock medium, statins, or ACAT inhibitors was done using the procedures described above with cells grown in six-well plates for 12 or 24 h, and total cholesterol was extracted in chloroform-methanol-double-distilled water (4:2:1 [vol/vol/vol]. The chloroform phase was separated, mixed with a 1:100 volume of polyoxyethylene 9-lauryl ether (Sigma), dried, and resuspended in the assay reaction buffer in the kit. Each treatment was duplicated in additional six-well plates, and cell lysates were prepared for the measurement of protein contents by using a BCA protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The concentrations of total cholesterol for each treatment were normalized with the protein contents and compared to those obtained with the mock medium treatment.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments, including flow cytometry, RL assay, immunofluorescence assay, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, were conducted using at least three independent measurements, and the effects of statins and ACAT inhibitors were analyzed by using a Student t test. The results were considered statistically significant when the P value was <0.05. The correlations of the mRNA levels of LDLR and NV RNA levels by statins, ACAT inhibitors, and lipoprotein-free medium in HG23 cells were calculated by using a simple linear regression model.

RESULTS

DNA microarray study.

Initial screening showed that ∼1,900 genes were either up- or downregulated >1.5-fold in replicon-bearing cells compared to the parental Huh7 cells. Genes in lipid (cholesterol) or carbohydrate metabolic pathways were significantly (P < 0.001) changed by the gene ontology analysis. Because bile acids, which were essential for the replication of PECs in cell culture (6), are important natural modulators of cholesterol pathways, I was particularly interested in the potential regulation genes in these pathways. Among genes in the cholesterol pathways, I found that genes for HMG-CoA synthase (0.57-fold; P = 0.04), squalene epoxidase (0.6-fold; P = 0.02), LDLR-related protein 5 (LRP5) (0.64-fold; P = 0.007), LRP12 (0.62-fold; P = 0.005), LRP10 (0.61-fold; P = 0.01), and ACAT2 (0.46-fold; P = 0.004) were significantly downregulated in the cells (Table 2). On the other hand, the genes for SHP (2.1-fold; P = 0.01), LDLR class A domain containing 3 (LDLRAD3) (1.7-fold; P = 0.004), and ACAT (carboxylesterase 1) (8.7-fold; P = 0.002) were significantly upregulated in the cells (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Genes in cholesterol pathways either up- or downregulated in NV replicon-bearing cells versus parental Huh-7 cells

| Function and gene name | Mean fold change | Pa |

|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol biosynthesis | ||

| HMG-CoA synthase | 0.57 | 0.04 |

| Squalene epoxidase | 0.6 | 0.02 |

| Bile acid related | ||

| SHP | 2.1 | 0.01 |

| Other cholesterol pathways | ||

| ACAT2 | 0.46 | 0.004 |

| ACAT (carboxylesterase 1) | 8.7 | 0.002 |

| LRP5 | 0.64 | 0.007 |

| LRP12 | 0.62 | 0.005 |

| LRP12 | 0.61 | 0.01 |

| LDLRAD3 | 1.7 | 0.004 |

P values were determined by using a Student t test of the three independent samples of HG23 and Huh-7 cells.

Effects of statins in NV replication and mRNA level of LDLR.

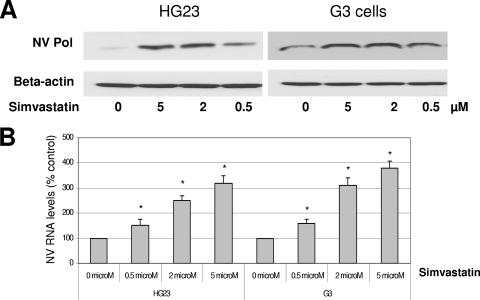

Based on the DNA microarray analysis, I hypothesized that the modulation of the cholesterol pathway would change norovirus replication in replicon-bearing cells. To test this hypothesis, I examined the role of inhibitors of cholesterol biosynthesis such as statins, zaragozic acid, and 6-fluoromevalonate in virus replication. First, statins are HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and downregulate cholesterol biosynthesis, and they reduce the cholesterol levels in blood via increasing the expression level of LDLR on cells. I examined simvastatin or lovastatin for NV replication in the present study. These statins showed little nonspecific cytotoxic effects on HG23 cells up to 20 μM, as determined by a cell cytotoxicity assay kit. When replicon-bearing cells, HG23 cells, or G3 cells were treated with simvastatin or lovastatin for 24 or 48 h, the levels of NV proteins or RNA were significantly increased (up to four- to fivefold) at concentrations higher than 2 μM (Fig. 1). However, zaragozic acid and 6-fluoromevalonate had little effect on NV replication in HG23 or G3 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effects of simvastatin on the expression of NV protein (A) and RNA (B) in replicon-bearing cells (HG23 and G3 cells). Semiconfluent cells were incubated with various concentrations of simvastatin for 48 h, and viral protein (NV Pol) and RNA were measured by Western blot analysis and real-time qRT-PCR, respectively. (A) Cell lysate was prepared after 48 h of the incubation for Western blot analysis with antibody to NV Pro-Pol or β-actin. (B) Total RNA was prepared after 48 h of the incubation for real-time qRT-PCR to detect NV genome. The NV RNA levels by the treatments were calculated by comparison to that performed with mock treatment. An asterisk indicates that the RNA level of the treatment was significantly increased compared to that of the mock treatment (P < 0.05).

Effects of SHP on NV replication.

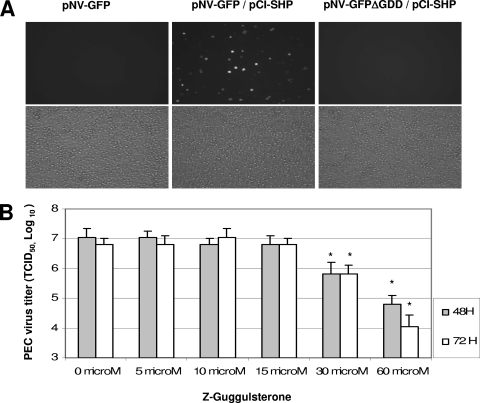

Since the mRNA level of SHP was upregulated in HG23 cells by DNA microarray study, I examined the role of SHP in the replication of NV by a cotransfection study with pNV-GFP or pNV-RL and pCI-SHP. Although the transfection of pNV-GFP or pNV-RL alone showed little evidence of virus replication, cotransfection with pCI-SHP significantly increased the cells expressing GFP or the expression level of RL in the cells (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Although the transfection of pNV-GFP alone in BHK21 or Vero cells did not produce GFP-positive cells above the level (0.02% ± 0.03%) of control MVA-T7-infected cells, cotransfection of pNV-GFP and pCI-SHP yielded ca. 1% (1.2% ± 0.04%) of cells expressing GFP as detected by flow cytometry analysis. Because the expression of SHP is induced by the activation of a bile acid receptor, farnesoid X receptor (FXR), these data suggest the bile acid pathway may be important in the replication of NV. I next examined the role of this FXR/SHP pathway in bile acid-mediated PEC replication in LLC-PK cells. I found that PEC replication in the presence of a bile acid (GCDCA) is correlated with the FXR/SHP pathway. The treatment with Z-guggulsterone, which is a bile acid antagonist of FXR, inhibited bile acid-mediated PEC replication (Fig. 2B), whereas mifepristone, which is an antagonist on pregnane X receptor or glucocorticoid receptors, did not show any effects on PEC replication. In addition, the real-time qRT-PCR results demonstrated that the treatment of GCDCA in LLC-PK cells for longer than 24 h increased the mRNA level of SHP, but in the presence of Z-guggulsterone, the SHP mRNA levels were not changed by GCDCA (data not shown). However, the treatment of HG23 cells with Z-guggulsterone up to 50 μM did not change the level of NV genome (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Role of FXR/SHP in the replication of NV and PEC. (A) Transfection of pNV-GFP alone, cotransfection of pNV-GFP with pCI-SHP, or cotransfection of pNV-GFPΔGDD with pCI-SHP into MVA-T7-infected cells. GFP-positive cells observed under a fluorescent (upper panel) or a light microscope (lower panel). Cotransfection of pNV-GFPΔGDD and pCI-SHP served as a negative control. (B) Effects of Z-guggulsterone on bile acid-mediated PEC replication. PEC was inoculated in confluent LLC-PK cells at an MOI of 0.5 and, after 1 h of incubation, medium containing GCDCA (100 μM) with various concentrations of Z-guggulsterone was replenished. Virus growth was measured after 48 or 72 h by using the 50% tissue culture infective dose method. An asterisk indicates that the virus titers were significantly reduced compared to that of mock-treatment (P < 0.05).

TABLE 3.

Expression of RL after transfection of pCI, pNV-GFP, pNV-RL, or pNV-RLΔGDD alone or with pCI-SHP or pCMV6-LDLR into MVA-T7-infected Vero cells

| Plasmid | Mean fold induction in Renilla luciferase ± SDa |

|---|---|

| pCI | 1 |

| pNV-GFP | 1.09 ± 0.2 |

| pNV-RL | 1.4 ± 0.3 |

| pNV-RLΔGDD | 0.95 ± 0.2 |

| pNV-RLΔGDD/pCI-SHP | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

| pNV-RLΔGDD/pCMV6-LDLR | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| pNV-RL/pCI-SHP | 3.6 ± 2.5* |

| pNV-RL/pCMV6-LDLR | 3.1 ± 2.3* |

| pNV-RL/pCI | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

Cell lysates were prepared after 20 h of transfection for determination of the RL activity; the level of RL after transfection of pCI was set as 1 for the induction. The standard deviations were calculated from at least three independent measurements. *, P < 0.05 compared to the pNV-RL group.

Role of ACAT in NV replication.

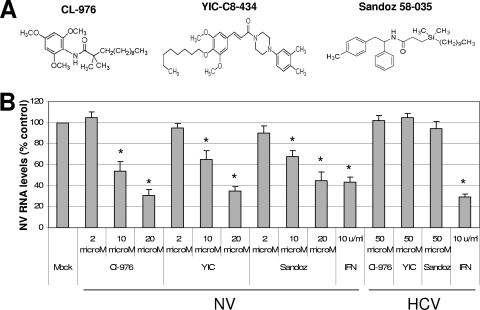

The activity of ACAT is also important in cholesterol biosynthesis by converting cholesterol to cholesteryl ester. I obtained known ACAT inhibitors, such as Cl-976, YIC-C8-434, pyripyropene A, or Sandoz 58-035 (Fig. 3A), to examine their effects on NV replication. First, I determined the highest concentration of each compound that showed little nonspecific cytotoxic effects in HG23 cells. There were minimum nonspecific cytotoxic effects by these compounds at concentrations up to 50 μM in the cells. When I examined the ACAT inhibitors in NV replication using replicon-bearing cells, I found that all of them significantly reduced the levels of NV proteins and RNA (Fig. 3B) at concentrations higher than 10 μM. The levels of NV RNA decreased up to 70% compared to mock treatment using 20 μM ACAT inhibitor concentrations at 24 h of treatment. The effective dose reducing 50% of the viral RNA (ED50) was determined to be 10, 15, and 15 μM for Cl-976, YIC-C8-434, and Sandoz 58-035, respectively. However, when I examined these compounds in the replication of HCV using similar replicon-bearing cells, there was no change in virus replication. The ED50 for HCV replication with Cl-976, YIC-C8-434, or Sandoz 58-035 was higher than 50 μM, the highest concentration showing little cytotoxicity in GS4.1 cells by each compound (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that the effects of the compounds are specific to NV replication. These data indicate that ACAT activity was associated with virus replication and that ACAT may be a novel therapeutic target for inhibiting norovirus replication. I also examined ezetimibe as a control and found that it did not affect the replication of NV and the mRNA level of LDLR in HG23 cells at concentrations up to 50 μM (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Anti-NV or anti-HCV effects of ACAT inhibitors. (A) Chemical structures of ACAT inhibitors. (B) One-day-old semiconfluent HG23 or GS4.1 cells were incubated with various concentrations of each ACAT inhibitor (Cl-976, YIC-08-434 [YIC], and Sandoz 58-026 [Sandoz]) or 10 U of alpha interferon/ml. After 24 h of incubation, total RNA was prepared for real-time qRT-PCR to detect NV or HCV genome and β-actin. The reduction of NV or HCV genome by the inhibitors was calculated by the comparison to that with mock treatment, after each genome level was normalized by the level of β-actin. An asterisk indicates that the RNA level of the treatment was significantly reduced compared to that of mock treatment (P < 0.05).

Role of LDLR in NV replication.

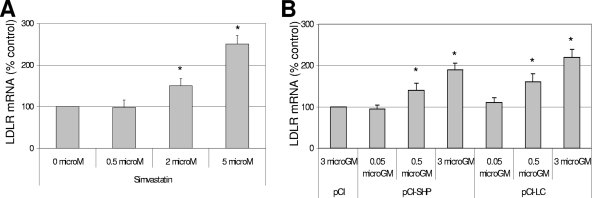

Since it is known that statins upregulate the expression of LDLR, I examined the levels of LDLR mRNA after cells were treated with stains. I found that both simvastatin and lovastatin increased the mRNA level of LDLR (Fig. 4A), but they had little effect on mRNA level of SHP as detected by real-time qRT-PCR. Interestingly, transfection of pCI-SHP or pCI-LC, both of which promoted NV replication in trans (Fig. 2A) (4), also increased the mRNA levels of LDLR (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the treatment with ACAT inhibitors (Cl-976, YIC-C8-434, and Sandoz 58-035) significantly reduced the mRNA levels of LDLR in correlation with reduced levels of NV proteins and RNA in HG23 cells (Fig. 3 and 5). However, the treatment of the ACAT inhibitors in HG23 cells did not change the mRNA levels of SHP (Fig. 5). Treatment of HG23 cells with zaragozic acid, 6-fluoromevalonate, or ezetimibe did not significantly change the mRNA levels of LDLR. The levels of LDLR mRNA and viral replication by various treatments of statins or ACAT inhibitors and transfection of pCI-SHP were significantly correlated in HG23 cells (R2 = 0.89) (Fig. 6A). I also found that the incubation of HG23 cells in lipoprotein-free FBS for 24 or 48 h increased the levels of both NV RNA and LDLR mRNA determined by real-time qRT-PCR (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Effects of treatment of simvastatin or transfection of pCI-SHP or pCI-LC on mRNA level of LDLR. One-day-old semiconfluent HG23 cells were either incubated with various concentrations of simvastatin or transfected with various concentrations of pCI-SHP or pCI-LC. After 24 h of incubation, the mRNA levels of LDLR or β-actin were measured by real-time qRT-PCR. (A) The mRNA levels of LDLR were calculated by comparison to the mock treatment after each RNA level was normalized to the level of β-actin. (B) Transfection of 3 μg of pCI served as a control for calculating mRNA levels of LDLR by the transfection with pCI-SHP or pCI-LC. An asterisk indicates that the RNA level of the treatment was significantly increased compared to the control (P < 0.05).

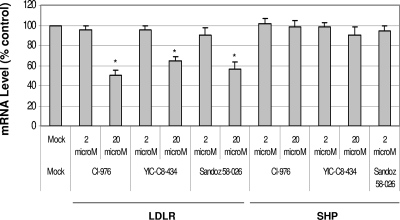

FIG. 5.

Effects of treatment of ACAT inhibitors in mRNA levels of LDLR or SHP. One-day-old semiconfluent HG23 cells were either incubated with mock medium or various concentrations of each inhibitor. After 24 h of incubation, the mRNA levels of LDLR, SHP, or β-actin were measured by real-time qRT-PCR. The mRNA levels of LDLR or SHP were calculated by the comparison to the mock treatment after each RNA level was normalized to the level of β-actin. An asterisk indicates that the RNA level of the treatment was significantly reduced compared to the control (P < 0.05).

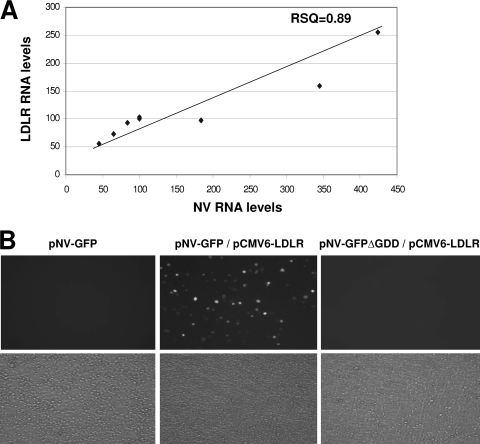

FIG. 6.

Correlation of the expression levels of LDLR and NV replication (A) and promotion of NV replication by the expression of LDLR (B). (A) The levels of LDLR RNA and NV genome versus treatment with various agents, including statins, ACAT inhibitors, and lipoprotein-free FBS, or the transfection of pCI-SHP or pCI-LC were significantly correlated (R2 = 0.89) by a simple linear regression model. These data are from both collated results from the other figures and additional experiments. (B) Transfection of pNV-GFP alone, cotransfection of pNV-GFP with pCMV6-LDLR, or cotransfection of pNV-GFPΔGDD with pCI-SHP into MVA-T7-infected BHK cells. GFP-positive cells were observed under a fluorescent (upper panel) or a light microscope (lower panel). Cotransfection of pNV-GFPΔGDD and pCI-SHP served as a negative control.

The role of LDLR in NV replication was confirmed by cotransfection study with pNV-GFP or pNV-RL alone or with the addition of either of these plasmids and pCMV6-LDLR. Although the transfection of pNV-GFP alone produced few GFP-positive cells, when LDLR was provided in trans by cotransfection of pCMV6-LDLR with pNV-GFP, I could observe significant numbers of GFP positive cells under a fluorescence microscope (Fig. 6B), indicating that LDLR promoted NV replication in cells. As demonstrated by flow cytometry analysis, the cotransfection of pNV-GFP and pCI-SHP in BHK21 or Vero cells produced ca. 1% (1.3% ± 0.03%) of cells expressed GFP, confirming the observations under a fluorescence microscope. When I examined the level of total cholesterol in the replicon-bearing cells treated with various concentrations of statins or ACAT inhibitors for 12 or 24 h, there was no significant change in the cholesterol levels with respect to the treatment.

DISCUSSION

Without a cell culture model, research on virus replication and antivirals of human noroviruses has been severely hampered. The development of norovirus replicon systems, such as replicon-bearing cells and plasmids with reporter genes (4, 7), has provided a crucial tool for the study of virus replication and antivirals. In the present study, I demonstrated the importance of cholesterol pathways in NV replication using the replicon systems, which may provide the information regarding therapeutic targets for norovirus infection. Cholesterol is one of the most essential biological molecules in the body, taking a part in membrane structures and acting as a precursor for the steroid hormones and bile acids. In a healthy adult, cholesterol is synthesized at ∼1 g/day, and the level of cholesterol (150 to 200 mg/dl) is maintained by controlling both de novo synthesis (major) and the dietary uptake (minor) of cholesterol. The synthesis and utilization of cholesterol are highly regulated by several mechanisms to prevent hypercholesterolemia, which may lead to accelerated atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases (8). De novo synthesis of cholesterol, which results from the conversion of acetyl-CoA, occurs mainly in the cytoplasm and microsomes of cells located in the liver and intestines (8). This process involves multiple steps and utilizes enzymes such as HMG-CoA synthase, HMG-CoA reductase, mevalonate kinase, isopentenyl transferase, and squalene epoxidase. HMG-CoA reductase is critically important in cholesterol synthesis, serving as a rate-limiting enzyme, and is subject to complex regulatory controls (8). The level of cholesterol is also regulated by the activity of ACAT, which converts excess intracellular free cholesterol to cholestryl ester in cells, and LDLR-mediated uptake and HDL-mediated reverse transport (8). By using DNA microarray analysis, I found that mRNA levels of two genes in cholesterol biosynthesis, HMG-CoA synthase and squalene epoxidase, were significantly reduced in HG23 cells compared to parental Huh-7 cells. Further downregulation of cholesterol biosynthesis with statins significantly promoted the expression NV RNA in HG23 cells, suggesting that cholesterol biosynthesis is important in the replication of NV in cells. Interestingly, it has been shown that during the replication of several viruses (including human immunodeficiency virus) (20), the pathway of cholesterol biosynthesis was upregulated in cells. In the case of HCV, it was demonstrated that statins reduced HCV replication by blocking the protein geranylgeranylation and the proper formation of viral replicase complexes (16, 31). Statins are HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and reduce plasma cholesterol levels by upregulating LDLR and promoting the uptake of LDL bound cholesterol to cells. In accordance with this, I found that the treatment of statins resulted in the increased expression of LDLR in HG23 cells, which was correlated with the increased level of virus replication. However, the treatment of zaragozic acid or 6-fluoromevalonate, both of which inhibit cholesterol biosynthesis, did not affect the levels of LDLR and NV replication in replicon-bearing cells. This may be due to different target molecules for zaragozic acid (a squalene synthase inhibitor) or 6-fluoromevalonate (a mevalonate-pyrophosphate decarboxylase inhibitor) from that of statins (a HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor) in cholesterol biosynthesis. Because statins are one of the most prescribed medicines for lowering blood cholesterol levels, it would be interesting to explore the possibility that taking statins may be a risk factor for norovirus infections in humans.

Synthesis of bile acids from cholesterol in the liver is an important mechanism for the natural loss of excess cholesterol. Bile acids are transported to the gallbladder and released into the small intestines, where they aid in the absorption of dietary lipids. The majority of bile acids in the intestines are returned to the liver via passive and active mechanisms (enterohepatic circulation) (26). Recent studies indicate that bile acids also function as hormonelike regulatory molecules with specific cellular receptors such as FXR (18, 23). The activation of FXR by bile acids induces the expression of various proteins including SHP, which represses the expression of cholesterol 7-hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in bile acid synthesis (23). This FXR/SHP pathway is well developed in hepatic, intestinal, and renal cells and participates in the regulation of cholesterol (and fatty acid) metabolism and glucose homeostasis (17, 18, 23, 25, 26, 29). Previously, we have shown that bile acids were essential for the replication of PEC in cell culture (6). As a potential mechanism for the phenomenon, we found that bile acid-mediated PEC replication in cells was related to the FXR/SHP pathway in the present study: an inhibitor of FXR pathway significantly reduced bile acid-mediated PEC replication in cells. Interestingly, we also found a correlation with NV replication and the FXR/SHP pathway in replicon-bearing cells: mRNA level of SHP was increased up to twofold. Cotransfection study with pCI-SHP confirmed that SHP promoted NV replication in trans in cells. Like the treatment with statins, the expression of SHP also increased the mRNA level of LDLR in cells. However, the treatment of HG23 cells with Z-guggulsterone up to 50 μM did not change the level of NV genome. Because the expression of SHP is already upregulated in the replicon-bearing cells, the treatment with Z-guggulsterone might not affect the virus replication in the cells.

Because the activity of ACAT in cells is an important factor for cholesterol biosynthesis, I examined ACAT inhibitors for NV replication. Inhibitors of ACAT have been examined in the past as therapeutic agents for various diseases including hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. When I examined known ACAT inhibitors such as Cl-976, YIC-C8-434, pyripyropene A, or Sandoz 58-035 in NV replication using replicon-bearing cells, I found that all of them significantly reduced the levels of NV proteins and RNA in a dose-dependent manner. These results indicate the potential for using ACAT inhibitors as antivirals and ACAT as a therapeutic target for noroviral infection. Interestingly, the treatment of ACAT inhibitors resulted in the reduction of mRNA level of LDLR in HG23 cells. Using treatments with statins and ACAT inhibitors, along with the expression of SHP, I found that the mRNA levels of LDLR in cells positively correlated with the replication of NV in cells. Cotransfection study with pNV-GFP and pCMV6-LDLR demonstrated that the expression of LDLR promoted the replication of NV in trans, confirming the importance of LDLR in NV replication in cells.

In conclusion, I demonstrated here the important of cholesterol pathways in NV replication in replicon-bearing cells. Specifically, I demonstrated that the expression of level of LDLR appeared to be positively correlated with NV replication in cells. Although I do not have clear explanation for this observation, it is possible that LDLR plays an important direct role in virus replication such as participating in viral replicase complexes as an essential cofactor. I intend to further study the role of LDLR in viral replication by examining its presence in viral replicase complexes in replicon-bearing cells by isolating viral replicase complexes and Western blot analysis. I will also evaluate the potential interactions between LDLR and viral proteins by coprecipitation assay and the mammalian two-hybrid assay. Furthermore, I demonstrated here the role of ACAT inhibitors as potential antinoroviral drugs. In the absence of therapeutic measures against norovirus infection, these findings may provide crucial information regarding antiviral drug development.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH COBRE (P20 RR016443-07).

I thank Jianfa Bai and Nanyan Lu for the DNA microarray study and David George for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buhaescu, I., and H. Izzedine. 2007. Mevalonate pathway: a review of clinical and therapeutic implications. Clin. Biochem. 40575-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang, K. O., and D. W. George. 2007. Bile acids promote the expression of hepatitis C virus in replicon-harboring cells. J. Virol. 819633-9640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang, K. O., and D. W. George. 2007. Interferons and ribavirin effectively inhibit Norwalk virus replication in replicon-bearing cells. J. Virol. 8112111-12118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, K. O., D. W. George, J. B. Patton, K. Y. Green, and S. V. Sosnovtsev. 2008. Leader of the capsid protein in feline calicivirus promotes the replication of Norwalk virus in cell culture. J. Virol. 829306-9317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, K. O., Y. Kim, K. Y. Green, and L. J. Saif. 2002. Cell-culture propagation of porcine enteric calicivirus mediated by intestinal contents is dependent on the cyclic AMP signaling pathway. Virology 304302-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, K. O., S. V. Sosnovtsev, G. Belliot, Y. Kim, L. J. Saif, and K. Y. Green. 2004. Bile acids are essential for porcine enteric calicivirus replication in association with down-regulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1018733-8738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, K. O., S. V. Sosnovtsev, G. Belliot, A. D. King, and K. Y. Green. 2006. Stable expression of a Norwalk virus RNA replicon in a human hepatoma cell line. Virology 353463-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlton-Menys, V., and P. N. Durrington. 2008. Human cholesterol metabolism and therapeutic molecules. Exp. Physiol. 9327-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edgar, R., M. Domrachev, and A. E. Lash. 2002. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 30207-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fankhauser, R. L., J. S. Noel, S. S. Monroe, T. Ando, and R. I. Glass. 1998. Molecular epidemiology of “Norwalk-like viruses” in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 1781571-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flynn, W. T., and L. J. Saif. 1988. Serial propagation of porcine enteric calicivirus-like virus in primary porcine kidney cell cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26206-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green, K. Y. 2007. Caliciviruses: the Noroviruses, 5th ed. Lippincott/The Williams & Wilkins Co., Philadelphia, PA.

- 13.Hansman, G. S., K. Natori, H. Shirato-Horikoshi, S. Ogawa, T. Oka, K. Katayama, T. Tanaka, T. Miyoshi, K. Sakae, S. Kobayashi, M. Shinohara, K. Uchida, N. Sakurai, K. Shinozaki, M. Okada, Y. Seto, K. Kamata, N. Nagata, K. Tanaka, T. Miyamura, and N. Takeda. 2006. Genetic and antigenic diversity among noroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 87909-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirokane, H., M. Nakahara, S. Tachibana, M. Shimizu, and R. Sato. 2004. Bile acid reduces the secretion of very low density lipoprotein by repressing microsomal triglyceride transfer protein gene expression mediated by hepatocyte nuclear factor-4. J. Biol. Chem. 27945685-45692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kageyama, T., S. Kojima, M. Shinohara, K. Uchida, S. Fukushi, F. B. Hoshino, N. Takeda, and K. Katayama. 2003. Broadly reactive and highly sensitive assay for Norwalk-like viruses based on real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 411548-1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapadia, S. B., H. Barth, T. Baumert, J. A. McKeating, and F. V. Chisari. 2007. Initiation of hepatitis C virus infection is dependent on cholesterol and cooperativity between CD81 and scavenger receptor B type I. J. Virol. 81374-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kullak-Ublick, G. A., B. Stieger, and P. J. Meier. 2004. Enterohepatic bile salt transporters in normal physiology and liver disease. Gastroenterology 126322-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makishima, M., A. Y. Okamoto, J. J. Repa, H. Tu, R. M. Learned, A. Luk, M. V. Hull, K. D. Lustig, D. J. Mangelsdorf, and B. Shan. 1999. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science 2841362-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mead, P. S., L. Slutsker, V. Dietz, L. F. McCaig, J. S. Bresee, C. Shapiro, P. M. Griffin, and R. V. Tauxe. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5607-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen, D. H., and D. D. Taub. 2004. Targeting lipids to prevent HIV infection. Mol. Interv. 4318-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norata, G. D., and A. L. Catapano. 2004. Lipid lowering activity of drugs affecting cholesterol absorption. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1442-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norlin, M., and K. Wikvall. 2007. Enzymes in the conversion of cholesterol into bile acids. Curr. Mol. Med. 7199-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parks, D. J., S. G. Blanchard, R. K. Bledsoe, G. Chandra, T. G. Consler, S. A. Kliewer, J. B. Stimmel, T. M. Willson, A. M. Zavacki, D. D. Moore, and J. M. Lehmann. 1999. Bile acids: natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science 2841365-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parwani, A. V., W. T. Flynn, K. L. Gadfield, and L. J. Saif. 1991. Serial propagation of porcine enteric calicivirus in a continuous cell line. Effect of medium supplementation with intestinal contents or enzymes. Arch. Virol. 120115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redinger, R. N. 2003. The coming of age of our understanding of the enterohepatic circulation of bile salts. Am. J. Surg. 185168-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redinger, R. N. 2003. The role of the enterohepatic circulation of bile salts and nuclear hormone receptors in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis: bile salts as ligands for nuclear hormone receptors. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 17265-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spann, K. M., K. C. Tran, B. Chi, R. L. Rabin, and P. L. Collins. 2004. Suppression of the induction of alpha, beta, and lambda interferons by the NS1 and NS2 proteins of human respiratory syncytial virus in human epithelial cells and macrophages. J. Virol. 784363-4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urizar, N. L., A. B. Liverman, D. T. Dodds, F. V. Silva, P. Ordentlich, Y. Yan, F. J. Gonzalez, R. A. Heyman, D. J. Mangelsdorf, and D. D. Moore. 2002. A natural product that lowers cholesterol as an antagonist ligand for FXR. Science 2961703-1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe, M., S. M. Houten, C. Mataki, M. A. Christoffolete, B. W. Kim, H. Sato, N. Messaddeq, J. W. Harney, O. Ezaki, T. Kodama, K. Schoonjans, A. C. Bianco, and J. Auwerx. 2006. Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature 439484-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyatt, L. S., B. Moss, and S. Rozenblatt. 1995. Replication-deficient vaccinia virus encoding bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase for transient gene expression in mammalian cells. Virology 210202-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye, J., C. Wang, R. Sumpter, Jr., M. S. Brown, J. L. Goldstein, and M. Gale, Jr. 2003. Disruption of hepatitis C virus RNA replication through inhibition of host protein geranylgeranylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10015865-15870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yee, E. L., H. Palacio, R. L. Atmar, U. Shah, C. Kilborn, M. Faul, T. E. Gavagan, R. D. Feigin, J. Versalovic, F. H. Neill, A. L. Panlilio, M. Miller, J. Spahr, and R. I. Glass. 2007. Widespread outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis among evacuees of Hurricane Katrina residing in a large “megashelter” in Houston, Texas: lessons learned for prevention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 441032-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]