Abstract

Ebola virus VP35 contains a C-terminal cluster of basic amino acids required for double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) binding and inhibition of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). VP35 also blocks protein kinase R (PKR) activation; however, the responsible domain has remained undefined. Here we show that the IRF inhibitory domain of VP35 mediates the inhibition of PKR and enhances the synthesis of coexpressed proteins. In contrast to dsRNA binding and IRF inhibition, alanine substitutions of at least two basic amino acids are required to abrogate PKR inhibition and enhanced protein expression. Moreover, we show that PKR activation is not only blocked but reversed by Ebola virus infection.

Ebola virus (EBOV) infections in humans cause severe hemorrhagic fevers with high mortality rates (21). A strong deregulation of the host immune response is observed in fatal cases and contributes to the manifestation of symptoms (16). The multifunctional EBOV protein VP35 serves as a polymerase cofactor essential for transcription and replication (18) and as a structural component for virus assembly (9). In addition, it contributes to filoviral immune modulation by impairing the cell's innate immune response by binding to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), blocking interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) phosphorylation and antagonizing dsRNA-dependent protein kinase R (PKR) activation (1, 2, 4, 19). IRF3 antagonism and dsRNA binding are mediated by a C-terminal group of basic amino acids (R305, K309, R312) (Fig. 1A). A single amino acid substitution of either arginine 309 or lysine 312 to alanine is sufficient to abrogate dsRNA binding and strongly reduce the IRF3 antagonism (2, 8, 14). In contrast, the abrogation of dsRNA binding by substitution R312A had no effect on PKR inhibition, which until now was suspected to reside within the first 200 N-terminal amino acids of the protein (4).

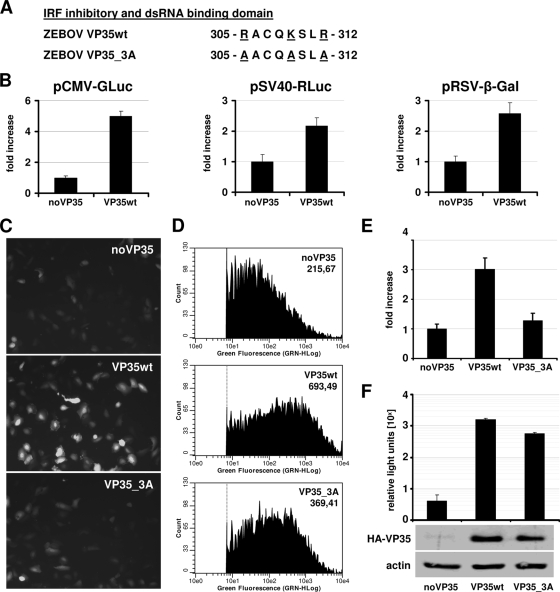

FIG. 1.

VP35 enhances the expression of cotransfected transgenes. (A) C-terminal region of VP35 containing conserved basic amino acids involved in dsRNA binding and interferon inhibition. Substituted amino acids in the mutant VP35_3A are indicated. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with 50 ng pCMV-GLuc (New England Biolabs), 20 ng pSV40-RLuc (Promega), or 500 ng pRSV-β-Gal along with 500 ng of pcDNA3.1-VP35/Z_NHA (VP35wt) or the corresponding empty vector (noVP35). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were lysed and reporter enzyme activity was determined (n = 6). (C and D) HEK293 cells were transfected with 50 ng pCAGGS-eGFP along with 500 ng of pcDNA3.1-VP35/Z_NHA (VP35wt) or pcDNA3.1-VP35/Z_NHA_3A (VP35_3A) or the corresponding empty vector (noVP35). (C) Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. (D) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis was performed with trypsinized cells. The mean fluorescence intensity is indicated in the top right corner of each plot. (E) Western blot analysis was performed with specific primary antibodies against GFP (B-2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or β-actin (Abcam) and IRDye800-labeled secondary antibodies (Rockland). Quantitative readout of the stained membrane was performed with the Odyssey infrared imager (LI-COR). The fluorescence intensity of the eGFP signal in relation to the actin background was calculated from three independent experiments. (F) Huh7 cells were transfected with pC-T7/Pol expressing the T7 RNA polymerase, pSV40-RLuc, all components of the EBOV polymerase complex (VP35wt or VP35_3A, NP, VP30, and L), and the 3E-5E-Luc minigenome containing the firefly luciferase gene flanked by the 3′ leader and 5′ trailer sequences of the EBOV genome that regulate viral gene transcription and genome replication. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, firefly luciferase activity was determined and normalized for Renilla luciferase activity. The data from three independent experiments are shown. VP35 expression was determined by Western blot analysis with specific antibodies against the hemagglutinin tag (HA.11; Covance) and β-actin.

Here we show that the PKR antagonistic property of VP35 is mediated by its C-terminal IRF inhibitory domain (IID) and significantly enhances transgene expression upon transient transfection. Alanine substitutions of at least two out of the three basic amino acids within the IID are required to eliminate this function. Furthermore, EBOV infection not only prevents PKR phosphorylation but is able to reverse it.

It has been noticed by us and others (19) that ectopic expression of VP35 along with other transgenes leads to a substantial increase in exogenous protein levels. To document this property of VP35, we expressed VP35 (EBOV species Zaire ebolavirus; GeneID 911827) along with various reporter genes in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells and found increased reporter activity in the presence of VP35 for any of the tested constructs (Fig. 1B), indicating that VP35 enhances ectopic gene expression independently of the used promoter and the expression cassette. The increase in protein expression mediated by VP35 could be visualized by fluorescence microscopy upon coexpression of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (Fig. 1C, top and middle). Assessment of green fluorescence intensity by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis (Fig. 1D) and determination of eGFP protein levels after Western blot staining (Fig. 1E) allowed for the quantification of eGFP expression levels. An approximately threefold increase in eGFP levels upon VP35 coexpression could be determined by both methods. Surprisingly, a VP35 mutant with alanine substitutions for amino acids R305, K309, and R312 (VP35_3A) (Fig. 1A) largely lost the ability to enhance transgene expression (Fig. 1C and D, bottom, and E). To exclude the possibility that the introduced mutations caused a general loss of function due to structural disorder, we verified the functionality of VP35 for replication and transcription using a minireplicon assay, which has been described previously (3, 17). The transfection of equal amounts of DNA yielded reduced VP35_3A protein levels, and thus a quantitative comparison of the polymerase complexes carrying wild-type or mutated VP35 was not possible. Nonetheless, the VP35 mutant was clearly able to support transcription and replication (Fig. 1F), demonstrating the functional integrity of the protein.

To elucidate the mechanistic basis of the VP35-dependent enhancement of protein expression, we first analyzed eGFP mRNA levels in transfected HEK293 cells. Total cellular RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent and treated with DNase I. Equal amounts of RNA were subjected to reverse transcription (RT) and RT-PCR analysis using primer pairs specific for eGFP and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA. Figure 2A shows that both transgenic eGFP mRNA and cellular GAPDH mRNA were synthesized to the same amount in the presence or absence of wild-type or mutant VP35, excluding an influence of VP35 on mRNA synthesis or stability.

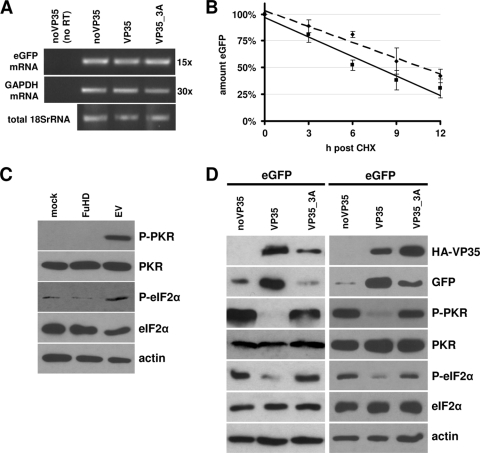

FIG. 2.

The IID of VP35 is essential for the PKR antagonistic function. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, total RNA was isolated and used for RT-PCR with primers specific for eGFP and GAPDH mRNAs. Reverse transcriptase was omitted to verify the specific amplification of cDNA (lane 1). (B) HEK293 cells were transfected as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cycloheximide (CHX; 100 μg/ml) was added to the cells. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points post-CHX treatment, and eGFP levels were quantified by Western blot analysis as described in the legend to Fig. 1E. The eGFP levels at the different time points and trend lines derived by linear regression in the presence (solid line) or absence (dashed line) of VP35 are shown. The experiment was performed in triplicate. (C) HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with empty vector pcDNA3.1 (EV), exposed to the transfection reagent FuGene HD (FuHD), or left untreated (mock). Twenty-four hours posttreatment, cells were analyzed by Western blot analysis as described above or previously elsewhere (11). (D) HEK293 cells were transfected as described for panel A (left) or with an increased amount of VP35_3A expression vector (2 μg) (right) to compensate for reduced protein levels and analyzed as described for panel C.

To assess a potential influence of VP35 on eGFP protein stability, we analyzed the eGFP decay after the addition of cycloheximide by quantitative Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 2B, VP35 did not increase eGFP protein stability.

It has been shown before that VP35 is able to interfere with PKR activity (4). Since PKR regulates translation by phosphorylating the eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α) (20), we analyzed the phosphorylation state of PKR and eIF2α by Western blot analysis as described previously (11). As shown in Fig. 2C, transfection of HEK293 cells with plasmid DNA, but not treatment with FuGene HD (Roche) alone, efficiently triggered PKR and eIF2α phosphorylation. Indeed, it has been observed previously that DNA transfection is able to trigger PKR activity and eIF2α phosphorylation, presumably through the generation of dsRNA during transcription of the plasmid DNA (10, 13). Interestingly, PKR activation by DNA transfection exclusively impairs translation of the transgenic mRNA and can be rescued by coexpression of PKR inhibitors. Hence, this method has been proposed and was frequently used to study the efficacy of PKR inhibitory molecules (10). Figure 2D shows that the phosphorylation levels of both PKR and eIF2α were significantly reduced in eGFP-transfected cells upon coexpression of VP35 (Fig. 2D, left, lanes 1 and 2). At the same time, eGFP protein levels were markedly increased, while the levels of endogenous proteins apparently remained unaffected. Most importantly, however, VP35_3A had lost the ability to antagonize PKR and eIF2α phosphorylation and concomitantly enhanced neither eGFP nor its own expression (Fig. 2D, left, lane 3). To exclude the possibility that the reduced protein level of VP35_3A caused the lacking PKR antagonism, we increased the amount of transfected VP35_3A expression plasmid (2 μg) (Fig. 2D, right). VP35_3A still showed a clear defect in blocking PKR and eIF2α phosphorylation; however, the slightly elevated eGFP protein levels indicate that the VP35 triple mutant retains minimal PKR antagonistic activity. Nonetheless, these results clearly demonstrate that the IID of VP35—and not the N terminus of the protein—mediates its PKR antagonistic function.

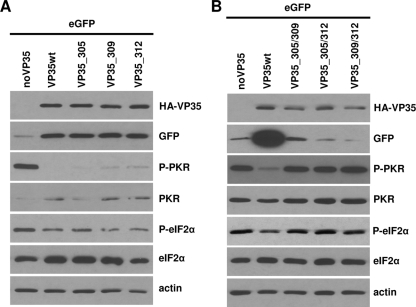

In apparent contrast to our observation, Feng et al. had previously excluded a contribution of R312 to VP35's PKR antagonistic function (4). To precisely clarify the contribution of amino acids R305, K309, and R312 of the IID to PKR inhibition, we created a complete set of VP35 expression vectors with single and double alanine substitutions by site-directed mutagenesis and assessed their effect on PKR phosphorylation. Strikingly, all single mutants fully retained the ability to abrogate PKR activity and enhance eGFP expression (Fig. 3A). In contrast, either combination of the double amino acid substitution caused a complete loss of PKR inhibition (Fig. 3B). Similar to mutant VP35_3A (Fig. 2D), we increased the amount of transfected VP35 expression plasmid (1 μg) to compensate for the lacking translation enhancement of the double mutants. Our results support the perception of Feng et al. (4) that substitution R312A alone, which readily abrogates dsRNA binding and IRF3 phosphorylation (2, 8), is not sufficient to abolish the inhibition of PKR by VP35. Instead, two alanine substitutions within the IID of VP35 are required to eliminate the PKR antagonistic property, suggesting that it mechanistically differs from dsRNA binding and IRF3 inhibition.

FIG. 3.

Substitution of two basic amino acids of the IID is required to abrogate the PKR antagonistic function of VP35. HEK293 cells were transfected as described in legend to Fig. 1C and in addition with VP35 mutants carrying single (A) or double (B) amino acid substitutions to alanine at the indicated positions. The amount of transfected expression plasmid for the double mutants was increased (1 μg) to compensate for reduced expression enhancement. Western blot analysis was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

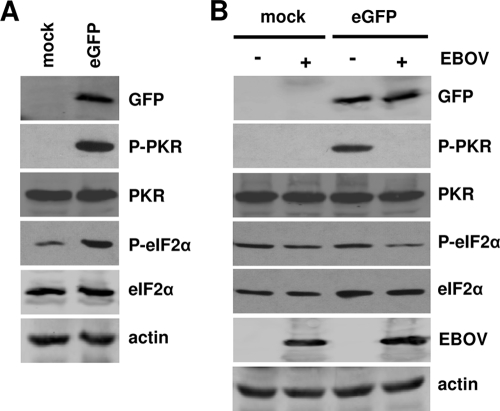

To date, inhibition of PKR by VP35 has been studied exclusively in transient transfection or heterologous virus systems (4). We therefore sought to investigate the impact of EBOV infection on PKR activity. HEK293 cells were transfected with an eGFP expression vector to trigger PKR activation as in the previous experiments and subsequently infected with the EBOV species Zaire ebolavirus, strain Mayinga, with a multiplicity of infection of 5 to achieve an infection rate of 100% (as verified by immunofluorescence analysis [data not shown]). Figure 4A shows increased PKR activation and eIF2α phosphorylation in transfected cells at the time point of EBOV infection. Twenty-four hours later, only background levels of phosphorylated eIF2α were detected in all samples, irrespective of whether the cells were infected or not and without any correlation to DNA transfection (Fig. 4B). Apparently, the transfection-induced eIF2α phosphorylation had already ceased in noninfected cells (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 1 and 3), prohibiting a conclusion about the ability of EBOV to enhance the translation of transgenic mRNA in this context. Nevertheless, these data show that EBOV infection did not induce eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 and 4). The transfection-induced activation of PKR remained clearly visible even 24 h postinfection. Strikingly, EBOV infection led to a strong reduction of PKR phosphorylation (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 4), suggesting that EBOV infection not only prevents PKR phosphorylation but is even able to reverse it.

FIG. 4.

EBOV infection is able to reverse PKR phosphorylation. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with 50 ng eGFP expression vector or left untreated (mock). (B) Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis or infected with EBOV with a multiplicity of infection of 5 where indicated. Twenty-four hours postinfection, cells were analyzed by Western blotting.

Our data show that in contrast to the current belief, the C-terminal IID of VP35 mediates the PKR antagonism and enhanced synthesis of coexpressed proteins. In analogy to the PKR inhibitory proteins NS1 of influenza virus or E3L of vaccinia virus, the dsRNA binding ability is not required to antagonize PKR (12, 15). However, despite the high sequence identity between the NS1 and VP35 dsRNA binding motifs, the property to additionally inhibit PKR is unique to VP35, illustrating the structural differences between both proteins that have been described recently (14). Intriguingly, our mutational analysis revealed that the dsRNA binding and PKR inhibitory functions of VP35 still have distinct mechanistic requirements. While single substitutions of amino acid 312 or 309 suffice to eliminate dsRNA binding (2, 14), the substitution of either two basic amino acids of the IID is required to abrogate PKR inhibition. Recombinant EBOVs carrying the single R312A mutation exhibited an impaired IRF3 antagonism and were markedly attenuated in cell culture and mice (5-7). Our data suggest that the elimination of only one more amino acid will help to further attenuate the virus and may thus be another important step toward the development of a potent EBOV vaccine.

Finally, we could show that EBOV infection not only blocks but reverses the phosphorylation of PKR, yielding a basis to elucidate the mechanism of PKR inhibition.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Takimoto and Y. Kawaoka for providing pC-T7/Pol, S. Becker and S. Bamberg for pCAGGS-eGFP, and C. Kirschning for pRSV-β-Gal. EBOV infections were performed in the BSL-4 facility of the Philipps University Marburg, Germany.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 535) and by start-up funds from Boston University to E.M.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basler, C. F., A. Mikulasova, L. Martinez-Sobrido, J. Paragas, E. Mühlberger, M. Bray, H. D. Klenk, P. Palese, and A. Garcia-Sastre. 2003. The Ebola virus VP35 protein inhibits activation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Virol. 777945-7956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cárdenas, W. B., Y. M. Loo, M. Gale, Jr., A. L. Hartman, C. R. Kimberlin, L. Martinez-Sobrido, E. O. Saphire, and C. F. Basler. 2006. Ebola virus VP35 protein binds double-stranded RNA and inhibits alpha/beta interferon production induced by RIG-I signaling. J. Virol. 805168-5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enterlein, S., K. M. Schmidt, M. Schümann, D. Conrad, V. Krähling, J. Olejnik, and E. Mühlberger. 2009. The Marburg virus 3′ non-coding region structurally and functionally differs from Ebola virus. J. Virol. 834508-4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng, Z., M. Cerveny, Z. Yan, and B. He. 2007. The VP35 protein of Ebola virus inhibits the antiviral effect mediated by double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. J. Virol. 81182-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartman, A. L., B. H. Bird, J. S. Towner, Z. A. Antoniadou, S. R. Zaki, and S. T. Nichol. 2008. Inhibition of IRF-3 activation by VP35 is critical for the high level of virulence of Ebola virus. J. Virol. 822699-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartman, A. L., J. E. Dover, J. S. Towner, and S. T. Nichol. 2006. Reverse genetic generation of recombinant Zaire Ebola viruses containing disrupted IRF-3 inhibitory domains results in attenuated virus growth in vitro and higher levels of IRF-3 activation without inhibiting viral transcription or replication. J. Virol. 806430-6440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartman, A. L., L. Ling, S. T. Nichol, and M. L. Hibberd. 2008. Whole-genome expression profiling reveals that inhibition of host innate immune response pathways by Ebola virus can be reversed by a single amino acid change in the VP35 protein. J. Virol. 825348-5358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartman, A. L., J. S. Towner, and S. T. Nichol. 2004. A C-terminal basic amino acid motif of Zaire ebolavirus VP35 is essential for type I interferon antagonism and displays high identity with the RNA-binding domain of another interferon antagonist, the NS1 protein of influenza A virus. Virology 328177-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang, Y., L. Xu, Y. Sun, and G. J. Nabel. 2002. The assembly of Ebola virus nucleocapsid requires virion-associated proteins 35 and 24 and posttranslational modification of nucleoprotein. Mol. Cell 10307-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman, R. J. 1997. DNA transfection to study translational control in mammalian cells. Methods 11361-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krähling, V., D. A. Stein, M. Spiegel, F. Weber, and E. Mühlberger. 2009. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus triggers apoptosis via protein kinase R but is resistant to its antiviral activity. J. Virol. 832298-2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langland, J. O., and B. L. Jacobs. 2004. Inhibition of PKR by vaccinia virus: role of the N- and C-terminal domains of E3L. Virology 324419-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leitner, W. W., L. N. Hwang, M. J. deVeer, A. Zhou, R. H. Silverman, B. R. Williams, T. W. Dubensky, H. Ying, and N. P. Restifo. 2003. Alphavirus-based DNA vaccine breaks immunological tolerance by activating innate antiviral pathways. Nat. Med. 933-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung, D. W., N. D. Ginder, D. B. Fulton, J. Nix, C. F. Basler, R. B. Honzatko, and G. K. Amarasinghe. 2009. Structure of the Ebola VP35 interferon inhibitory domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106411-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, S., J. Y. Min, R. M. Krug, and G. C. Sen. 2006. Binding of the influenza A virus NS1 protein to PKR mediates the inhibition of its activation by either PACT or double-stranded RNA. Virology 34913-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahanty, S., and M. Bray. 2004. Pathogenesis of filoviral haemorrhagic fevers. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4487-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mühlberger, E. 2007. Filovirus replication and transcription. Future Virol. 2205-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mühlberger, E., M. Weik, V. E. Volchkov, H. D. Klenk, and S. Becker. 1999. Comparison of the transcription and replication strategies of Marburg virus and Ebola virus by using artificial replication systems. J. Virol. 732333-2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prins, K. C., W. B. Cardenas, and C. F. Basler. 2009. Ebola virus protein VP35 impairs the function of interferon regulatory factor-activating kinases IKKɛ and TBK-1. J. Virol. 833069-3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadler, A. J., and B. R. Williams. 2007. Structure and function of the protein kinase R. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 316253-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. 2008. Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Fact sheet no. 103. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs103/en/.