Abstract

Many pathogenic orthopoxviruses like variola virus, monkeypox virus, and cowpox virus (CPXV), but not vaccinia virus, encode a unique family of ankyrin (ANK) repeat-containing proteins that interact directly with NF-κB1/p105 and inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway. Here, we present the in vitro and in vivo characterization of the targeted gene knockout of this novel NF-κB inhibitor in CPXV. Our results demonstrate that the vCpx-006KO uniquely induces a variety of NF-κB-controlled proinflammatory cytokines from infected myeloid cells, accompanied by a rapid phosphorylation of the IκB kinase complex and subsequent degradation of the NF-κB cellular inhibitors IκBα and NF-κB1/p105. Moreover, the vCpx-006KO virus was attenuated for virulence in mice and induced a significantly elevated cellular inflammatory process at tissue sites of virus replication in the lung. These results indicate that members of this ANK repeat family are utilized specifically by pathogenic orthopoxviruses to repress the NF-κB signaling pathway at tissue sites of virus replication in situ.

Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) comprises a family of key transcriptional regulators of inducible factors needed by the immune system. Members of this family are all dimeric transcription factors, which in mammals comprise five elements: RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, NF-κB1 (p105/p50), and NF-κB2 (p100/p52) (19). These structurally related proteins form various homodimers and heterodimers via their N-terminal Rel homology domains. In unstimulated cells, NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm as latent complexes by the physical association of their Rel homology domains with NF-κB inhibitory proteins, IκBs. NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 are produced as precursor proteins, p105 and p100, which share structural similarity with IκBs in their C-terminal portion. Like IκBs, the full-length p105 and p100 proteins bind mature NF-κBs and sequester them in the cytoplasm (19). NF-κB activation is central to many pathological states and is typically mediated by the proteasomal degradation of the prototypical IκB member, IκBα (19). This canonical NF-κB signaling pathway can be triggered by various inducers, which elicit signal transduction events that lead to the activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. Activated IKK phosphorylates IκBα, triggering its polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, releasing associated NF-κB subunits to translocate into the nucleus. Unlike the noncanonical p100-mediated pathway, the constitutive processing of p105 to produce p50 by the proteasome is not regulated by agonist stimulation. However, p105 is phosphorylated by IKK after the activation of the canonical pathway, targeting it for complete degradation by the proteasome to release associated NF-κB subunits (19).

Cowpox virus (CPXV) is a member of the genus Orthopoxvirus, family Poxviridae, and is antigenically and genetically related to variola virus (VARV) (the causative agent of smallpox), vaccinia virus (VACV), ectromelia virus (ECTV), and monkeypox virus (MPXV). Despite its name, wild rodents are believed to be the natural reservoir for CPXV, whereas humans are subject to occasional zoonotic infections with pathogenicities that range from mild to severe (8, 9). The eradication of smallpox, along with the cessation of routine vaccination with VACV, has created a susceptible population niche for various animal orthopoxviruses, particularly MPXV and CPXV, to zoonotically infect humans with increasing frequency. CPXV infection is considered an emerging zoonotic agent, with several reports of the virus being transmitted from cats to human beings (2, 18, 33). For immunocompromised patients, severe generalized CPXV infections have been documented (31).

Successful microbial pathogens have evolved complex and efficient methods to overcome or manipulate innate and adaptive immune mechanisms, and one common target for manipulation by both viral and bacterial pathogens is NF-κB (11). Since the orchestration of the inflammatory response to infection and tissue damage is arguably the key physiological function of NF-κB (14), interference with the activation of NF-κB represents an exceptional strategy for a successful zoonotic pathogen to exploit to counter multiple immune processes through the targeting of a single host regulatory pathway. Because of their large genomes, which typically encode ∼200 proteins, and their unusual independence from the host nuclear transcriptional machinery (28), poxviruses are especially well suited to affect the cytoplasmic activation of NF-κB.

Recently, following a yeast two-hybrid screen of the unique proteins encoded by the genome of VARV against several human cDNA libraries, we demonstrated that a novel ankyrin (ANK) repeat-containing protein encoded by VARV, called G1R, could bind NF-κB1/p105 and was a bona fide inhibitor of the NF-κB signaling pathway in cultured cells (27). Functional orthologs of VARV G1R also exist for other pathogenic orthopoxviruses, including ECTV, CPXV, and MPXV, but the gene is conspicuously fragmented in VACV. Due to the strict human-specific nature of VARV, CPXV was chosen as the surrogate model system to study the in vitro and in vivo properties of this novel family of poxviral NF-κB inhibitors. In this report, we present the characterization of the targeted CPXV gene knockout virus (vCpx-006KO) that lacks the expression of this ANK repeat NF-κB inhibitor. Our results demonstrate that in stark contrast to wild-type CPXV, infection with vCpx-006KO rapidly induces high levels of a variety of NF-κB-controlled proinflammatory cytokines from infected human myeloid (THP1) cells. Furthermore, the vCpx-006KO virus was attenuated for disease pathogenesis in mice following intratrachael (i.t.) inoculation and induced a significantly elevated cellular inflammatory response at tissue sites of virus replication in the lung. These data indicate that the CPXV ANK repeat 006 protein interferes with the NF-κB-induced proinflammatory pathway in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and infections.

African green monkey kidney (CV-1) cells (ATCC CCL70) were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM; Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 1× MEM nonessential amino acids (Cellgro; Mediatech, Herndon, VA), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco BRL). Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells (ATCC CRL-1573), Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81), baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells (ATCC CCL-10), and HeLa cells (ATCC CCL-2) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 10% FBS. THP1 (human acute monocytic leukemia cell line) cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% FBS. For differentiation, THP1 cells were stimulated for 18 h with 100 ng/ml of phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA; Sigma). All cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The virus was allowed to adsorb to the cells for 1 h, at which point medium containing virus was removed and replaced with fresh medium.

Viruses.

The wild-type Brighton Red strain of CPXV was propagated in CV-1 cells. A derivative of CPXV (vCpx-gfp) was created by the intergenic insertion of an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) cassette between open reading frames CPXV-107 and CPXV-108 of the CPXV genome. The EGFP cassette was driven by a synthetic VACV early/late promoter (vv sE/L) described previously (6). The transfer plasmid was transfected into CPXV-infected CV-1 cells by use of Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resultant EGFP-tagged control CPXV virus (vCpx-gfp) produced fluorescent green foci and was purified following three rounds of plaque purification. As for the construction of the CPXV open reading frame 006 (CPXV-006) knockout virus vCpx-006KO (see Fig. 2A), regions flanking the CPXV-006 coding region were amplified and cloned into pDONR221 (Invitrogen) using Gateway technology (Invitrogen). The left flank was amplified using primers 006UF (5′-AAAGCAGGCTGGATATCGCCGGTCGTCATAAG-3′) and 006UR (5′-AAAAGTTGGGTGACCTTCATTCTCACCGTCGT-3′). The right flank was amplified using primers 006DF (5′-AATAAAGTTGGGTGCGTATTAAGGGACGAGTCA-3′) and 006DR (5′-GAAAGCTGGGTATTCCCGCTCTCCAATCATTA-3′). Between the flanking regions, a cassette that expressed EGFP under the vv sE/L promoter was inserted. The transfer plasmid was transfected into CPXV-infected CV-1 cells by use of Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resultant CPXV-006 knockout virus (vCpx-006KO) produced fluorescent green foci and was purified following three rounds of plaque purification. For control purposes, a CPXV-006 revertant virus (vCpx-006RV) was constructed by PCR amplification of the region between primers 006UF and 006DR. The resultant 2.4-kb fragment was transfected directly, following sequence verification, into vCpx-006KO virus-infected CV-1 cells. The revertant virus was purified by the selection of colorless plaques, the result of homologous recombination between the 006KO-EGFP fragment of vCpx-006KO and the intact 006 coding region of the revertant fragment. All virus stocks were grown in CV-1 cells and purified by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion and two successive sucrose gradient sedimentations as described previously (10).

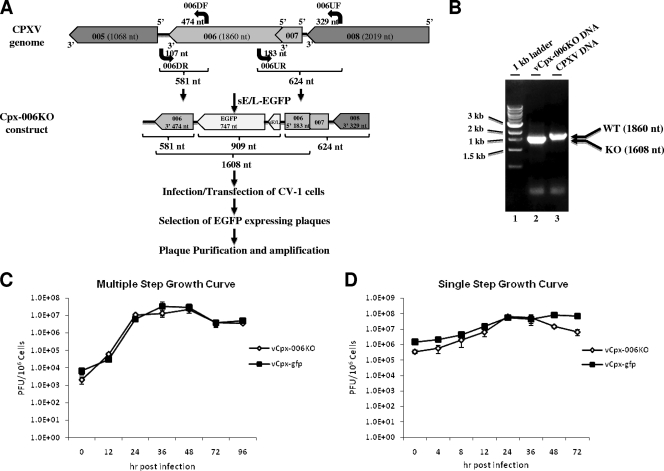

FIG. 2.

Construction of vCpx-006KO virus. (A) Regions flanking CPXV-006 were amplified and cloned into pDONR221. Between the flanking regions, a cassette that expressed EGFP under the vv sE/L promoter was inserted, resulting in the deletion of 65% of the open reading frame. Following infection/transfection, fluorescent plaques were amplified after plaque purification (three times). nt, nucleotide; DF, downstream forward; DR, downstream reverse; UF, upstream forward; UR, upstream reverse. (B) The purity of the recombinant virus was confirmed by PCR. WT, wild type; KO, knockout. (C and D) Multiple-step (C) and single-step (D) growth curves were performed. CV-1 cells were infected with vCpx-gfp (solid squares) or vCpx-006KO (open diamonds) at an MOI of 0.1 (C) or 5 (D), and cells were then collected at various times postinfection. The virus titers were determined in triplicate following serial dilution onto CV-1 cells.

Reagents and antibodies.

Lyophilized recombinant human tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) was reconstituted at a concentration of 20 μg/ml in a sterile filtered solution of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (3.2 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, 1.3 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl [pH 7.4]) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO); aliquots were stored at −80°C. Cycloheximide and cytosine β-d-arabinofuranoside (araC) were obtained from Sigma. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies for IκBα, NF-κB/p65, NF-κB1/p105/p50, IKKα, IKKβ, and phospho-IKKα(Ser180)/IKKβ(Ser181) as well as rabbit monoclonal antibodies for phospho-NF-κB1/p105 (Ser933) and phospho-IκBα (Ser32) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Rabbit polyclonal antibody for histone H1 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and mouse monoclonal antibody for β-actin was obtained from Ambion. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse immunoglobulin G antibodies were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory.

Single-step and multiple-step growth curves.

CV-1 cells were seeded into six-well dishes, and confluent monolayers (1 × 106 cells) were infected with either wild-type vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 or 0.1, for single-step and multiple-step growth curves, respectively, for 1 h. The inoculum was removed, and the cell monolayer was washed three times with complete medium. Samples were collected at various times postinfection (0, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h postinfection [hpi] for the single-step growth curve and 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72, and 96 hpi for the multiple-step growth curve), and the virus was collected and then titrated back onto CV-1 monolayers by serial dilution in triplicate. Plaques were scored at 48 hpi, using a fluorescent microscope, and plotted using Excel.

Plasmid constructs.

Gene cloning was done using Gateway cloning technology (Invitrogen). A codon-optimized version of CPXV-006 (GeneArt) was PCR amplified and incorporated into plasmid pDNOR222 (Invitrogen) by using the BP Clonase enzyme mix (Invitrogen) to generate an entry clone. The resultant entry clone was then subjected to an LR recombination reaction with the destination vector pcDNA-DEST40 (Invitrogen) to generate the corresponding expression clone. This cloning strategy resulted in an expressed protein that was tagged at the C terminus with a V5 tag.

Measurement of levels of cytokine induction.

Human myeloid THP1 cells were plated in multiwell plates in the presence of PMA (100 ng/ml) for 12 to 18 h. The following day, media were replaced with fresh media, and the cells were either mock infected or infected with vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO virus (at an MOI of 3). At various time points following the start of the infection, the supernatants were collected, and the levels of the secreted cytokines TNF, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay human cytokine assay kits (ebioscience) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Whenever mentioned, cells were also lysed directly in RLT buffer (Qiagen), and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) for quantification of cytokine mRNA levels using real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR.

Generally, 2 μg of total RNA was used to create cDNA. Initially, genomic DNA was removed from total RNA using the DNA-free kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Following the removal of genomic DNA, 1 μl of 100 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates and 1 μl of 50 μg/ml random hexamer primers were added, and the mixture was incubated for 5 min at 65°C. The tube was then allowed to cool down to room temperature, and 6 μl of a solution containing 5× reaction buffer, 3 μl 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 1 μl RNasin (Promega), and 1 μl Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) was added. The resulting mixture was incubated for 1 h at 42°C, followed by a second incubation for 15 min at 72°C. The final reaction mixture was diluted 1:10 with sterile H2O and used for SYBR green-based real-time PCR. Four microliters of diluted cDNA was added to 21 μl of PCR mix containing 0.5 U Taq polymerase (NEB), 1× Thermo Pol buffer, 0.1× SYBR green dye (Molecular Probes), 0.5× ROX reference dye (Invitrogen), 160 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Invitrogen), 4 mM MgCl (Invitrogen), 4 ng forward primer, and 4 ng reverse primer. The resulting 25-μl reaction mixture was run using an ABI 7300 real-time PCR machine under the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

Preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts.

THP1 cells were either mock infected or infected with vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO virus (at an MOI of 3) for 30 min. Following infection, cells were harvested, and both nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared using NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were harvested at different time points, washed with PBS, and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]). Protein samples were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (23) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (GE Healthcare) in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol, and 0.1% SDS [pH 8.2] [38]). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline-0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20 [pH 7.6]) for 1 h at room temperature. Specific proteins were detected with primary antibody diluted 1:2,500 in 5% nonfat milk-TBST followed by a secondary incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antiserum, diluted 1:5,000 in 5% nonfat milk-TBST. The membrane was then incubated in enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce), and autoradiography was used to detect specific proteins.

Transfections and luciferase assays.

HeLa cells (1 × 104 cells) were seeded at 50% confluence onto 96-well plates the day before being transfected. Cells were transfected according to the manufacturer's protocol using 0.5 μl Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Gibco BRL) and 0.2 μg DNA, in serum-free MEM, per each well. The DNA was a 1:1 mix of NF-κB reporter vector to constitutive expression vector. The NF-κB reporter vector used was the Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) pNF-κB-Luc plasmid, which gives inducible NF-κB-dependent expression of firefly (Photinus pyralis) luciferase driven by a synthetic promoter comprising a TATA box preceded by five direct repeats of the sequence 5′-TGGGGACTTTCCGC-3′ containing the NF-κB binding element first identified in the kappa light-chain gene enhancer (34). The constitutive expression vector used was the Promega (Madison, WI) pUC-based pRL-TK vector, which gives low-level constitutive expression of sea pansy (Renilla reniformis) luciferase from the promoter of the herpesvirus thymidine kinase gene. At 6 h posttransfection, FBS was added to the medium for a final concentration of 10%. At 24 h posttransfection, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were either mock infected or infected with CPXV, vCpx-gfp, or vCpx-006KO virus at an MOI of 10. At 4 hpi, the cells were treated in the absence or presence of 20 ng/ml TNF-α and harvested 4 h later (8 hpi). To harvest the cells and to determine luciferase values, the Promega dual-luciferase reporter assay system was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The relative changes in expression were determined by normalizing the ratios of firefly to sea pansy luciferase activities in each virus-infected cell group to the value obtained for mock-infected cells.

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy.

HeLa cells (3 × 104 cells) plated onto coverslips were either mock transfected or transiently transfected with 2 μg of pcDNA-DEST40 expressing codon-optimized CPXV-006. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma), permeabilized using 0.2% Triton X-100 (MP Biomedicals), and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS. Coverslips were incubated with mouse anti-V5 (Invitrogen) diluted 1:150 in PBS containing 3% BSA for 30 min at 37°C. Coverslips were then incubated with goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) diluted 1:400 in PBS containing 3% BSA for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Following staining, coverslips were mounted onto microscope slides with 7.5 μl of Vecta-Shield mounting medium with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for visualization of nuclei. Cells were visualized using the 40× objective of an Olympus DSU-IX81 spinning-disc confocal/deconvolution fluorescent microscope.

i.t. inoculation of mice.

i.t. inoculation of mice with viruses was done as previously described (24). Briefly, groups of five 8-week-old female C57BL/6 specific-pathogen-free mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were infected with sequential 10-fold dilutions of vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO from 106 to 104 PFU of virus to determine the effective lethal dose of 50% of the mice. This parameter is defined as the quantity of virus that would cause sufficiently severe respiratory distress in half of the respective infected mice to necessitate their euthanasia (euthanasia was performed according to American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines). For all experiments, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane gas or by intraperitoneal injection of a combination of 80 to 90 mg/kg of body weight ketamine-HCl and 12 to 15 mg/kg xylazine diluted in sterile isotonic sodium chloride. The mice were placed in a supine position, and the skin at the ventral aspect of the throat was surgically prepared. A 0.5-cm incision was made on the ventral aspect of the throat, and a sterile microchip (Bio Medic Data Systems, Seaford, DE) was inserted under the skin to the left of the thorax over the pectoral muscles. This microchip allowed each animal to be assigned a unique identification number and also allowed body temperature measurements daily using a transponder DAS-5007 reader (Bio Medic Data Systems, Seaford, DE). The trachea was carefully exposed by blunt dissection, and 30 μl of diluted virus or PBS was injected i.t. through a 30-gauge needle. The surgical wound was closed with sterile tissue glue. Animals were monitored twice a day for up to 14 days following surgery, where weight, temperature, and physical observations of the mice (grooming habits, facial swelling, secretions, and removal of hair, etc.) were recorded daily. Criteria for euthanizing the mice, which were approved by the University of Florida animal care committee, included open-mouth breathing, severe difficulty in breathing, body temperature of 30°C or lower as measured by the microchips, or greater than 30% body weight loss from beginning weight. Reaching any one of these criteria was considered to be grounds for sacrifice. The axial artery was severed with scissors to collect blood, and mice were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of 150 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (Schering-Plough Animal Health, Union, NJ), and a complete necropsy was preformed. Organs were placed in 10% buffered formalin (Protocol; Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) for histopathological examination and immunohistochemical analysis. All animal work was performed according to institutionally approved protocols and guidelines. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test with the use of SigmaStat 3.1 software. Significance was established when the P value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

We recently described a novel class of ANK repeat-containing poxviral proteins from VARV and several other pathogenic orthopoxviruses, with VACV being a notable exception. Members of this VARV G1R family, including versions from ECTV, MPXV, and CPXV, were shown to be capable of interacting with NF-κB1/p105 and inhibited the NF-κB signaling pathway in transfected cells (27). In order to evaluate the physiological relevance of these proteins during viral infection, we were interested in assessing the impact of knocking out this novel NF-κB inhibitor on viral replication both in vitro and in vivo. CPXV open reading frame 006 (CPXV-006) shares a 93.49% similarity with VARV G1R and was shown to interact with both NF-κB1/p105 and the Skp1 component of the cellular SCF complex (27). Moreover, the transient expression of CPXV-006 was shown to inhibit NF-κB-induced transcriptional activities (27). Because of the absence of an animal model for VARV pathogenesis, the Brighton Red strain of CPXV was utilized as the surrogate model virus to study the role of this family of ANK repeat proteins in the NF-κB signaling pathway in cultured cells and in viral pathogenesis in vivo.

CPXV-006 is expressed at both early and late times during CPXV infection.

Given the potential role of the CPXV-006 protein in altering innate host-mediated immune responses (27), it was necessary to confirm that CPXV-006 was produced early during infection, a time at which most other known intracellular poxviral immunomodulating proteins are expressed (28). To assess temporal expression during infection, CPXV-006 mRNA levels were examined at various time points following CPXV infection of THP1 cells by using real-time PCR. For control purposes, mRNA expression levels of CPXV genes, 021, 097, and 066, orthologs of known vaccinia virus early (C11R), intermediate (G8R), and late (F17R) genes, respectively, were also assessed. Elevated levels of CPXV-006 mRNA were detected early after infection with parental CPXV and were detected within 1 hpi (Fig. 1A), consistent with an early expression pattern. A similar kinetic of mRNA expression was observed for CPXV-021 (Fig. 1B), a close ortholog of the VACV early C11R gene. Interestingly, an additional increase in CPXV-006 mRNA levels was observed at later time points during infection, beginning at 9 hpi (Fig. 1A). However, when infections proceeded in medium containing araC, a pyrimidine nucleoside analog that inhibits poxviral DNA replication (22) as well as intermediate and late gene expression, this late increase in CPXV-006 mRNA levels was not detected (Fig. 1A). This result suggests that CPXV-006 undergoes an early/late expression pattern. As a control, infected cells were analyzed concomitantly for mRNA levels of CPXV-097 and CPXV-066, orthologs of the known intermediate and late VACV proteins G8R and F17R, respectively (Fig. 1C and D). Both CPXV-097 and CPXV-066 mRNA levels were detected at very low levels at early time points postinfection and in greater amounts at 8 and 12 hpi in the absence of araC (Fig. 1C and D). However, when infections proceeded in medium containing araC, CPXV-097 and CPXV-066 mRNA levels were severely reduced.

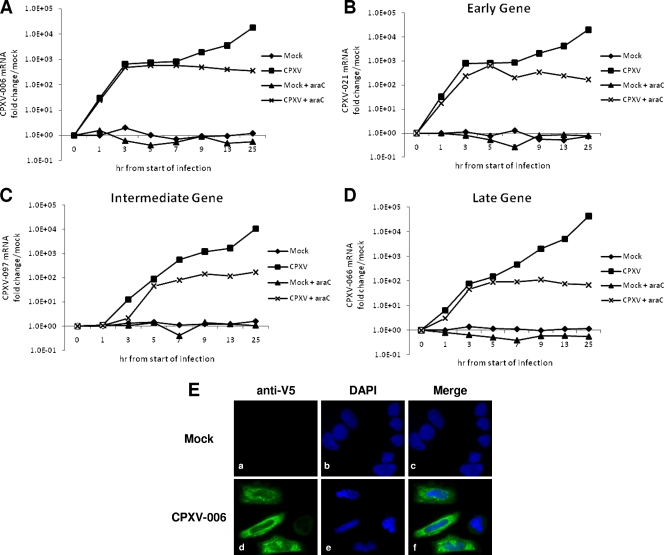

FIG. 1.

CPXV-006 is expressed at both early and late times during CPXV infection. THP1 cells were either mock infected or infected with CPXV at an MOI of 3. (A to D) At the indicated time points, cells were lysed, and mRNA levels of the CPXV genes 006 (A), 021 (B), 097 (C), and 066 (D) were assessed using real-time PCR. (E) Indirect immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy analysis demonstrating the expression pattern of CPXV-006 in transiently transfected HeLa cells. Cells were either mock transfected (a to c) or transiently transfected with pcDNA-DEST40 expressing codon-optimized CPXV-006 (d to f). At 24 h posttransfection, cells were sequentially labeled using mouse anti-V5 and anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 antibodies, respectively. Cells were visualized using the 40× objective of an Olympus DSU-IX81 spinning-disc confocal/deconvolution fluorescent microscope.

We next investigated the subcellular localization of a V5 epitope-tagged CPXV-006 (V5-CPXV-006) following transient transfection in uninfected HeLa cells. For control purposes, HeLa cells were transfected with the parent plasmid pCDNA-DEST40 (Invitrogen) and stained with anti-V5 antibody (Fig. 1Ea to c). The transient expression of V5-CPXV-006 demonstrated a uniform staining pattern exclusively throughout the cytoplasm of the cell (Fig. 1Ed to f).

Construction of a CPXV-006 knockout virus.

In order to study the biological significance of CPXV-006, a recombinant CPXV deficient of this gene (vCpx-006KO) was constructed. In brief, ∼65% of CPXV-006 was replaced with sequences encoding EGFP under the control of the vv sE/L promoter (Fig. 2A). The Cpx-006KO construct was then transfected into CPXV-infected CV-1 cells. The recombinant vCpx-006KO virus was plaque purified by selecting virus clones expressing EGFP. The purity of the recombinant virus was confirmed by PCR (Fig. 2B). Primers corresponding to the 5′ and 3′ ends of CPXV-006 were used and amplified a 1,860-nucleotide fragment from the wild-type CPXV template (Fig. 2B, lane 3). The product amplified from the purified recombinant viral DNA template, using the same primers, was 1,608 nucleotides long, without any sign of the longer wild-type product (Fig. 2B, compare lane 2 to lane 3). For control purposes, an EGFP-tagged version of wild-type CPXV (vCpx-gfp) was also constructed (not shown) by an intergenic insertion of the sequences encoding EGFP, under the control of the vv sE/L promoter, between CPXV genes 107 and 108. Both in vitro and in vivo characterizations of vCpx-gfp indicated that the EGFP insertion at this location had no effect on the replication of the virus (data not shown). In addition, insertion at this 107/108 intergenic region was shown previously to have no impact on the biological properties of CPXV (16).

In order to test the expression integrity of the genes flanking CPXV-006 in the newly constructed knockout virus (vCpx-006KO), mRNA expression levels of CPXV-005 and CPXV-007 were assessed. No detectable difference in the mRNA levels of either one of these two genes between both vCpx-gfp and vCpx-006KO viruses was observed (data not shown), indicating that the deletion of CPXV-006 had no effect on the expression levels of the flanking genes.

In order to assess the ability of the vCpx-006KO virus to replicate and spread in vitro, both single- and multiple-step growth curves were performed. There was no replication or spread pattern difference between vCpx-gfp and vCpx-006KO viruses in the nonhuman primate cell line CV-1 (Fig. 2C and D), where both viruses exhibited similar replication and spread kinetics. In addition, both viruses exhibited similar replication and spread kinetics in THP1 (human), HEK293 (human), HeLa (human), Vero (primate), and BHK (hamster) cells (data not shown). These results indicate that CPXV-006 is not required for viral replication or spread in human monocytic leukemia cell lines as well as standard CPXV-permissive fibroblasts from multiple species in vitro.

vCpx-006KO virus induces a variety of NF-κB-controlled proinflammatory cytokines from virus-infected THP1 cells.

Some viruses proactively induce NF-κB signaling for use as a transcriptional factor to express viral genes (reviewed in references 20 and 32). However, NF-κB can also be potentially deleterious to virus-infected cells, as it induces the expression of multiple host innate immune proteins such as antiviral cytokines, antigen presentation pathway members, and proinflammatory chemokines that attract immune cells to the area of virus infection, thereby compromising virus survival (15). Thus, successful viruses must carefully micromanage the timing and duration of NF-κB activation to ensure its usefulness as a transcription factor while restricting its antiviral effects (12, 20, 32). Among those viruses that manipulate NF-κB, members of the orthopoxvirus family are known to express multiple proteins that regulate NF-κB activities.

Recently, we demonstrated that transiently transfected CPXV-006 could inhibit NF-κB signaling in response to activation by TNF (27). In order to assess the impact of deleting the CPXV-006 gene on the ability of infectious CPXV to regulate the NF-κB-controlled induction of proinflammatory cytokines, human THP1 cells were treated with PMA to promote monocytic differentiation and were infected for various time points, up to 24 hpi, with vCpx-006KO (at an MOI of 3), and the kinetics and levels of various proinflammatory cytokines were assessed at the mRNA and protein levels. For control purposes, THP1 cells were also either mock infected or infected with parental vCpx-gfp that expresses the CPXV-006 protein. Both the culture supernatants and the virus-infected cells were collected at various time points, starting from 15 min following the beginning of infection, to monitor cytokine protein and mRNA levels, respectively. In contrast to vCpx-gfp, vCpx-006KO uniquely induced the secretion of high levels of a variety of NF-κB-controlled proinflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, from infected THP1 cells (Fig. 3A to C). In contrast, infection of THP1 cells with vCpx-006KO induced MCP-1 secretion to levels that were indistinguishable from those induced by vCpx-gfp (Fig. 3D). As shown in Fig. 3A and B, the kinetics of induction of both TNF-α and IL-1β were very rapid, starting by 1 h after the beginning of infection, maxing out within 2 h, and lasting for at least 24 hpi. In contrast, the induction of IL-6 was delayed and was first detected at around 12 hpi (Fig. 3C). Analysis of cytokine mRNA levels by using real-time PCR revealed a similar induction of cytokine mRNA levels following the infection of THP1 cells with vCpx-006KO (data not shown). To confirm that the loss of CPXV-006 expression in vCpx-006KO was responsible for the observed induction of cytokines from THP1 cells, we generated a revertant virus in which CPXV-006 was restored, and we tested the ability of this revertant (vCpx-006RV) to block cytokine production from THP1 cells. In contrast to vCpx-006KO, the vCpx-006RV virus was able to block cytokine induction from THP1 cells in a manner that was indistinguishable from that of the wild-type virus (data not shown). These results demonstrate the unique ability of the vCpx-006KO virus, which lacks only the expression of the CPXV-006 protein, to induce the expression and subsequent secretion of various proinflammatory cytokines controlled by NF-κB.

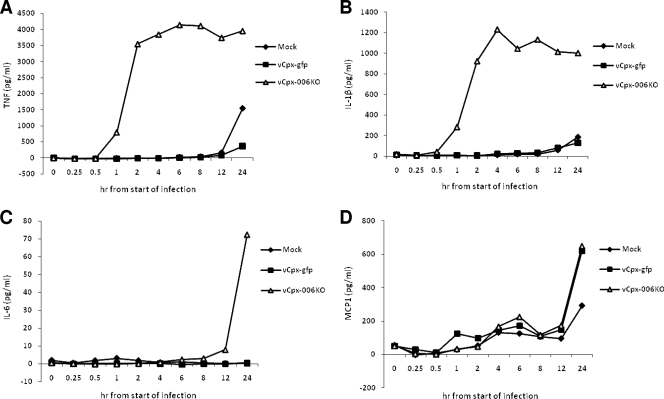

FIG. 3.

vCpx-006KO virus infection of THP1 cells induces the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in vitro. THP1 cells were allowed to differentiate for 12 to 18 h in the presence of PMA and then either mock infected or infected with vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO virus at an MOI of 3. Cell supernatants were collected at the indicated time points, and levels of secreted TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C), and MCP-1 (D) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

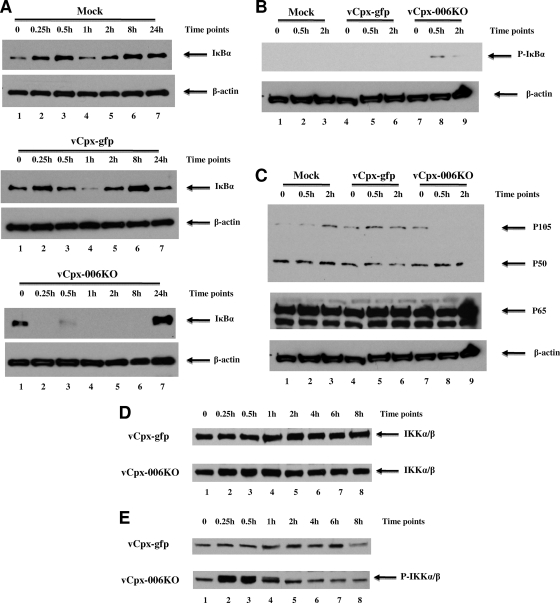

vCpx-006KO virus infection of THP1 cells induces the phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα and NF-κB1/p105.

As NF-κB activation is typically mediated by the phosphorylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation of the prototypical IκB member, IκBα (19), we next evaluated the level and the phosphorylation status of IκBα during vCpx-006KO infection of THP1 cells (Fig. 4). Cells were either mock infected or infected with vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO virus (at an MOI of 3) and harvested at different time points, and the level of IκBα was assessed using Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A). In contrast to mock or vCpx-gfp infection, a rapid degradation of IκBα was observed as early as 0.25 h following the start of infection of THP1 cells with vCpx-006KO (Fig. 4A, bottom, lanes 2 to 6). By 24 h after infection, however, the level of IκBα returned back to normal in the vCpx-006KO-infected cells. (Fig. 4A, bottom, lane 7). Since the phosphorylation of IκBα is a prerequisite for its degradation, we next investigated the phosphorylation state of IκBα in virus-infected THP1 cells using Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 4B, the phosphorylation of IκBα was observed at 0.5 and 2 h after infection of THP1 cells with vCpx-006KO virus (top, lanes 8 and 9) but not after mock infection or infection with vCpx-gfp (top, lanes 1 to 6). These results demonstrate that in contrast to vCpx-gfp, infection of THP1 cells with the vCpx-006KO virus induces the phosphorylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation of IκBα.

FIG. 4.

vCpx-006KO virus infection of THP1 cells induces the phosphorylation of the IKK complex and the degradation of NF-κB cellular inhibitors. THP1 cells were first differentiated with PMA and then either mock infected or infected with vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO virus at an MOI of 3. At various time points postinfection, cells were harvested and lysed, and extracts were prepared. Equal amounts of proteins were resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and subjected to Western blot analysis. Shown are data for antibodies specific for IκBα (A), phospho-IκBα (P-IκBα) (B), NF-κB1/p105/p50 and NF-κB/p65 (C), IKKα/β (D), and phospho-IKKα/β (E). Levels of β-actin were determined as internal loading controls using anti-β-actin antibodies.

Previous results from our laboratory demonstrated the ability of ectopically expressed CPXV-006, in the absence of any other viral proteins, to stabilize NF-κB1/p105 and prevent its TNF-induced degradation (27). To determine the impact of deleting CPXV-006 expression on the stability of NF-κB1/p105 during viral infection, the level of NF-κB1/p105 was assessed following infection of THP1 cells with vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO. In contrast to the mock control or vCpx-gfp, infection of THP1 cells with vCpx-006KO induced the complete degradation of NF-κB1/p105 (Fig. 4C, top, lanes 8 and 9). Nevertheless, no change in the level of either NF-κB1/p50 or NF-κB/p65 was detected (Fig. 4C, top and middle, respectively). These results indicate that the absence of CPXV-006 expression eliminated the ability of the infecting CPXV to stabilize NF-κB1/p105, consequently leading to its degradation.

vCpx-006KO virus induces the phosphorylation and activation of the IKK complex.

Since the infection of THP1 cells with the vCpx-006KO virus uniquely induced the degradation of both IκBα and NF-κB1/p105, we were interested in assessing the phosphorylation (and activation) status of the IKKα/β subunits of the IKK complex. THP1 cells were infected with vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO virus (at an MOI of 3) and harvested at different time points, and both the level and the phosphorylation state of the IKKα/β subunits of the IKK complex were assessed using Western blot analysis (Fig. 4D and E, respectively). As shown in Fig. 4D, the level of total IKKα/β proteins remained unchanged throughout the infection of THP1 cells with either virus. However, in contrast to vCpx-gfp, infection of THP1 cells with vCpx-006KO transiently induced an increased level of phosphorylation of IKKα/β for up to 1 hpi (Fig. 4E, bottom, lanes 2 to 4), an essential step in the activation of the NF-κB pathway.

vCpx-006KO virus induces nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of NF-κB.

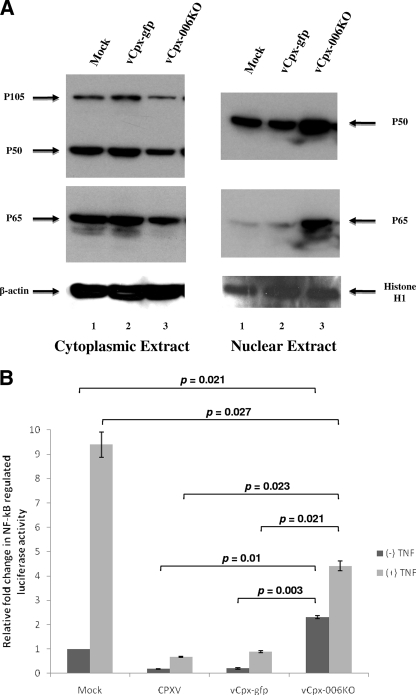

Given that the activation of the NF-κB pathway involves the nuclear translocation of the p50/p65 heterodimer, we next assessed the effect of vCpx-006KO virus infection on the subcellular localization of the p50/p65 heterodimer. THP1 cells were mock infected or infected with vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO virus (at an MOI of 3) for 30 min and harvested, and the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were prepared. The levels of NF-κB1/p105/p50 and NF-κB/p65 were then assessed for each of these extracts using Western blot analysis (Fig. 5A). In contrast to both mock-infected and vCpx-gfp-infected cells, cytoplasmic extracts from vCpx-006KO-infected cells exhibited a reduction in the levels of NF-κB1/p50/p105 and NF-κB/p65 (Fig. 5A, left, compare lanes 1 to 2 with lane 3, top and middle, respectively). A corresponding increase in the levels of both NF-κB1/p50 and NF-κB/p65 was observed for the nuclear extracts from cells infected with vCpx-006KO virus but not from mock-infected or vCpx-gfp-infected cells (Fig. 5A, right, compare lanes 1 to 2 with lane 3, top and middle, respectively). As loading controls, levels of β-actin (cytoplasmic extracts) (Fig. 5A, bottom left) and histone H1 (nuclear extracts) (Fig. 5A, bottom right) were examined and shown to be unchanged. These results clearly demonstrate that vCpx-006KO virus, lacking CPXV-006 expression, specifically induces the nuclear translocation of NF-κB1/p50 and NF-κB/p65, both of which are components of the transcriptionally active NF-κB heterodimer NF-κB/p65/p50. It is worth pointing out that the observed reduction in the level of NF-κB1/p105 in the cytoplasmic extract of cells infected with vCpx-006KO (Fig. 5A, top left, lane 3) is probably a reflection of the vCpx-006KO-induced degradation of NF-κB1/p105, as demonstrated in Fig. 4C.

FIG. 5.

vCpx-006KO virus induces the nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of NF-κB. (A) THP1 cells were first differentiated with PMA and then either mock infected or infected with vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO virus at an MOI of 3. At 30 min postinfection, cells were harvested, and both cytoplasmic (left) and nuclear (right) extracts were prepared. The levels of NF-κB1/p105/p50 and NF-κB/p65 were then assessed in each of these extracts using Western blot analysis. As loading controls, levels of β-actin and histone H1 were also determined. (B) HeLa cells were cotransfected with a 1:1 mix of plasmids pNFκB-Luc (gives inducible NF-κB-dependent expression of the firefly luciferase gene) and pRL-TK (gives low-level constitutive expression of the sea pansy luciferase gene). At 24 h posttransfection, cells were either mock infected or infected with untagged CPXV, vCpx-gfp, or vCpx-006KO (at an MOI of 10) for 4 h. Cells were either left untreated or treated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for 4 h and then assayed for both sea pansy and firefly luciferase activities. The values presented represent the averages of data from three independent transfections. Statistical significance was calculated using the Student t test.

In order to directly assess the impact of deleting CPXV-006 on the ability of CPXV to inhibit inducible NF-κB-regulated gene expression, the effect of vCpx-006KO virus infection upon the expression of the firefly luciferase gene under the control of the NF-κB-regulated promoter was examined. Transfected HeLa cells were either mock infected or infected with untagged CPXV, vCpx-gfp, or vCpx-006KO (at an MOI of 10) for 4 h and then treated for 4 h in the presence or absence of TNF-α. As shown in Fig. 5B, cells infected with untagged CPXV or vCpx-gfp showed almost no change in firefly luciferase activity in response to TNF-α treatment, reflecting the ability of the viral protein(s) to block TNF-induced NF-κB transcriptional activities. In contrast, TNF-α treatment of mock-infected THP1 cells resulted in a ∼9.4-fold relative increase in firefly luciferase activity over that observed for untreated cells (Fig. 5B). Moreover, infection of cells with untagged CPXV or vCpx-gfp virus, in the absence of TNF-α treatment, did not induce the expression of luciferase; instead, the level of expression of the luciferase genes was much lower than that in mock-infected cells (Fig. 5B). This reduction probably reflects the inhibition exerted by the suite of input CPXV- or vCpx-gfp-encoded protein(s) on background NF-κB transcriptional activities. In contrast, infection of cells with vCpx-006KO virus, in the absence of TNF-α treatment, induced a statistically significant level of luciferase expression (Fig. 5B), indicating that the deletion of CPXV-006 relieved, at least partially, the block exerted by the parental CPXV over NF-κB transcriptional activities. In addition, TNF-α treatment of cells infected with vCpx-006KO virus resulted in an even higher level of luciferase expression than that observed for untreated vCpx-006KO or the TNF-treated vCpx-gfp virus-infected cells (Fig. 5B), indicating that the lack of CPXV-006 expression hampered the ability of CPXV or vCpx-gfp to fully block the TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB transcriptional activities. However, the level of TNF-α-induced luciferase expression in vCpx-006KO-infected cells was significantly lower than that observed following TNF-α treatment of mock-infected cells, possibly a reflection of the effect of other CPXV NF-κB inhibitors expressed by this virus.

Effects of CPXV-006 on virulence of CPXV in mice.

All of the above-mentioned in vitro characterization studies carried out for vCpx-006KO virus suggest a proinflammatory role of this protein in vivo as well. To address this, we used the i.t. inoculation route that was recently established as a more controlled method for poxvirus introduction into the lungs of C57BL/6 mice (24). This approach represents a more consistent delivery method and ensures that a more precise number of viral particles are distributed throughout the lower respiratory tract by bypassing the nasal and oral cavities and also avoids the technical difficulties associated with aerosol and intranasal inoculations (24). The choice to infect C57BL/6 mice instead of the BALB/c strain traditionally used to examine poxvirus pathogenesis was based on the fact that C57BL/6 is the murine strain more commonly used as the genetic background for commercially available transgenic mice, which would benefit future studies.

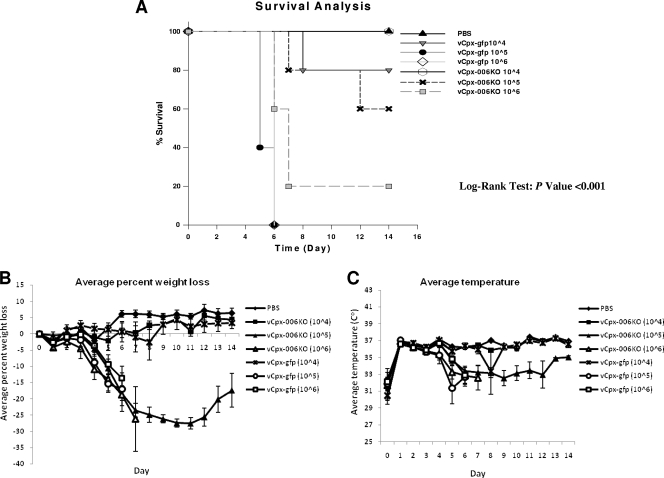

In order to assess the effect of the CPXV-006 protein on CPXV virulence in vivo, C57BL/6 mice were i.t. inoculated with various doses (104, 105, and 106 PFU) of vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO and monitored for signs of distress. By 6 days postinfection, all of the wild-type control vCpx-gfp-infected mice from the groups of mice given 105 and 106 PFU/mouse had to be euthanized (Fig. 6A). In contrast, 20% and 60% of mice inoculated with 105 and 106 PFU/mouse, respectively, of vCpx-006KO virus survived (Fig. 6A). Statistical analysis using the log-rank test revealed a significant difference between survival curves (P < 0.001). A calculated effective lethal dose for 50% of the mice of 1.8 × 105 PFU/mouse was observed for vCpx-006KO virus, while that for vCpx-gfp virus was 2.6 × 104 PFU/mouse. Moreover, the onset of signs of disease such as weight loss, hypothermia, hunched posture, breathing difficulty, edema, lethargy, and poor grooming was more rapid and more pronounced in vCpx-gfp-infected mice than in vCpx-006KO-treated mice (Fig. 6B and C). These results indicate that the loss of CPXV-006 expression appeared to somewhat attenuate CPXV in C57BL/6 mice in terms of disease progression and mortality.

FIG. 6.

vCpx-006KO virus is slightly attenuated in i.t. inoculated C57BL/6 mice. Groups of five C57BL/6 mice were inoculated i.t. with 30 μl of PBS or various doses (104, 105, and 106 PFU) of vCpx-gfp or vCpx-006KO and monitored for signs of distress. (A) Survival rates for C57BL/6 mice after i.t. inoculation of PBS, vCpx-gfp, or vCpx-006KO. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test with the use of SigmaStat 3.1 software. Significance was established when the P value was less than 0.05. (B) The change in body weight of mice from each group is presented as the average percent weight loss that was obtained by comparison with initial body weight. (C) Average recorded body temperatures for mice from each group.

i.t. inoculation of vCpx-006KO virus induces an elevated inflammatory response.

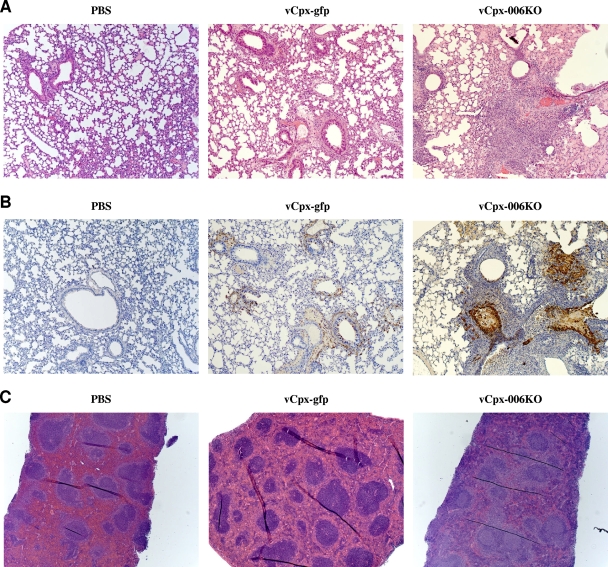

In order to evaluate the effect of deleting CPXV-006 on the lung tissue pathology of i.t. CPXV infections in mice, the severity of inflammation for both vCpx-gfp- and vCpx-006KO-infected mice was examined. Hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E)-stained sections of lungs from PBS-, vCpx-gfp-, and vCpx-006KO-inoculated mice were evaluated for the presence of inflammation, hemorrhage, edema, necrosis, and fibrosis (Fig. 7A). As expected, lung sections from vCpx-gfp-infected mice had mild to moderate, multifocal, mixed inflammation that was focused mainly around the bronchioles, as observed for VACV infection (A. Rice and R. W. Moyer, unpublished data) (Fig. 7A, middle). In addition, a mild to moderate, multifocal, vascular necrosis, occasionally associated with mild to moderate hemorrhage and edema, was also observed. In contrast, H&E staining of lung sections from mice infected with vCpx-006KO demonstrated significantly elevated levels of inflammation, massive edema, and cellular infiltrates (Fig. 7A, right). As both vCpx-gfp and vCpx-006KO viruses express EGFP, lung sections were subjected to immunohistochemistry staining for EGFP in order to locate sites of virus replication. Figure 7B (middle and right) demonstrates that signs of histological lesions were associated mostly with tissue sites of virus replication. No signs of histological lesions were observed in the lungs of control (PBS-inoculated) mice (Fig. 7A, left).

FIG. 7.

Histopathology of lung and spleen sections. (A and B) Representative lung sections from mice after i.t. inoculation with 30 μl PBS, 105 PFU vCpx-gfp, or 105 PFU vCpx-006KO were subjected to either H&E staining (A) or immunohistochemistry staining for green fluorescent protein (B) (magnification, ×100). (C) Representative spleen sections from mice after i.t. inoculation with 30 μl PBS, 105 PFU vCpx-gfp, or 105 PFU vCpx-006KO were subjected to H&E staining (magnification, ×50).

Given that the spleen represents the immunological filter of the blood and the site of formation of activated lymphocytes, we next examined tissue sections derived from spleens of mice inoculated with PBS, vCpx-gfp, or vCpx-006KO (Fig. 7C). In contrast to mice inoculated with PBS or vCpx-gfp, spleen sections from mice inoculated with vCpx-006KO had activated follicles (Fig. 7C, compare both left and middle to right), an indication of a strong inflammatory response. Collectively, these results indicate that infection with vCpx-006KO, lacking CPXV-006 expression, induces a significant inflammatory process, consistent with the interference of CPXV-006 with the virus-induced proinflammatory pathway.

DISCUSSION

Many viruses have evolved sophisticated countermeasures to evade host defenses at multiple levels down to the cellular level. Because of their large genomes and their unusual independence from host transcriptional machinery in the nucleus (28), poxviruses are especially well suited to affect the activation of the NF-κB pathway in the cytoplasm. We recently described a novel class of ANK repeat-containing proteins from VARV and other pathogenic orthopoxviruses like ECTV, MPXV, and CPXV, but not VACV, whose individual members are capable of interacting directly with NF-κB1/p105 (27). This is the first such reported interaction between any viral protein and NF-κB1, and the transient expression of this viral protein alone inhibited the NF-κB signaling pathway in TNF-stimulated cells (27). In the present study, we further examined the mechanistic details of this observation in the context of a live-virus infection by using CPXV as the model system to evaluate viral pathogenesis in vivo.

First, we evaluated the temporal expression of CPXV-006 and concluded that it has an early/late expression pattern, and thus, the protein is expressed essentially constitutively during CPXV infection. Moreover, the transient expression of CPXV-006 alone demonstrated a uniform staining pattern exclusively throughout the cytoplasm of the cell. In order to evaluate the physiological relevance of CPXV-006 during viral infection, a targeted knockout virus with the EGFP cassette replacing the CPXV-006 locus, called vCpx-006KO, which lacks the expression of this ANK repeat NF-κB inhibitor, was constructed and characterized both in vitro and in vivo. We did not detect any replication or spread kinetic differences between vCpx-006KO and the control EGFP-tagged version of wild-type CPXV (vCpx-gfp) in cell culture, indicating that CPXV-006 is not required for viral replication or spread in vitro. However, in contrast to vCpx-gfp, vCpx-006KO virus induced the rapid expression and secretion of a variety of NF-κB-controlled proinflammatory cytokines in virus-infected THP1 human myeloid cells. This cytokine induction was coupled to a swift phosphorylation of the IKK complex and the consequent phosphorylation and degradation of the NF-κB cellular inhibitors IκBα and NF-κB1/p105. The degradation of NF-κB1/p105 is consistent with results from our recent report demonstrating the ability of CPXV-006, in the absence of any other viral protein, to specifically bind and stabilize NF-κB1/p105, but not IκBα, and thus prevent its TNF-α-induced degradation (27). Note that ectopically expressed CPXV-006 does not confer similar protection against TNF-α-induced degradation to IκBα (27). Thus, the vCpx-006KO-induced degradation of IκBα raises the possibility that the deletion of CPXV-006 from CPXV triggers other changes in virus infection that hinder its known ability to prevent the degradation of IκBα (29). As CPXV-006 also interacts with Skp1 (27) and the interaction between Skp1 and poxviral ANK/F-box proteins was previously proposed to play a role in dictating the target specificity of SCF1 ubiquitin ligases (36, 39), the demonstration of a stabilizing effect of CPXV-006 on NF-κB1/p105 (27) seems to contradict this idea. Similarly, the interaction of myxoma virus M-T5 with both Skp1 and Akt does not cause the degradation of Akt but instead actually stabilizes it (40), whereas the presence of M-T5 was previously credited for the observed increased degradation of p27/Kip (21). Therefore, in the absence of any substantial evidence, we cannot conclude whether the interaction of CPXV-006 with Skp1 is relevant to the observed stability of NF-κB1/p105 in the presence of CPXV-006 or whether it is simply serving a completely different purpose.

Consistent with our recent results demonstrating the ability of ectopically expressed CPXV-006 to block TNF-induced nuclear translocation and the transcriptional activity of NF-κB (27), infection with vCpx-006KO virus, lacking the expression of CPXV-006, uniquely induced the nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of NF-κB. These results clearly demonstrate that CPXV-006 contributes significantly to the ability of CPXV to block NF-κB activation in vitro. Moreover, i.t. inoculated vCpx-006KO virus was dramatically attenuated in C57BL/6 mice compared to the vCpx-gfp control, consistent with previous reports demonstrating that the pathogenicity of other mutant poxviruses that are incapable of expressing NF-κB-inhibitory proteins is attenuated in infected laboratory animals (5, 17, 37). Furthermore, detailed histological examinations revealed a significantly elevated inflammatory process at lung tissue sites of vCpx-006KO virus replication. We also noted direct signs of follicular activation in the spleen, consistent with a role for CPXV-006 in interference with the virus-induced proinflammatory pathway in vivo.

The rapid kinetics with which CPXV or vCpx-006KO blocks or induces, respectively, the activation of the NF-κB pathway and the subsequent secretion of NF-κB-regulated proinflammatory cytokines in THP1 cells strongly suggest that CPXV-006 might be localized within the input virions. Although the proteomic components of the CPXV virion have not yet been reported, MPXV-003, the MPXV homolog of VARV G1R and CPXV-006, was recently identified as being virion associated in a comparative proteomic analysis of MPXV virion particles using liquid chromatography coupled with (tandem) mass spectrometry (25). Given both sequence and functional similarities between MPXV-003 and CPXV-006 (27), we suggest that CPXV-006 is thus likely to be virion associated. This is also consistent with the demonstrated early/late expression pattern of CPXV-006. It would also explain the rapid kinetics with which these viruses, vCpx-gfp and vCpx-006KO, inhibit and induce, respectively, NF-κB activation, where the presence of CPXV-006 in the input CPXV virion would allow the protein to rapidly interfere with the NF-κB activation process.

The induction of the NF-κB pathway results in the activation of transcription factors that are believed to act as a “master switch” for inflammation by regulating the transcription of genes that are crucial for innate and acquired immune responses (1, 3, 4). Thus, interference with the activation of NF-κB represents an exceptional strategy for pathogens like poxviruses to counter multiple immune processes through the targeting of a single regulatory process. Indeed, many poxviruses are known to encode multiple proteins that affect the activation of NF-κB in a variety of different ways (7, 13, 29, 35). However, unlike previously described poxviral NF-κB inhibitors, this class of ANK repeat-containing proteins, including CPXV-006, has the ability to interfere with the activation of NF-κB by specifically targeting regulatory events leading to the activation of NF-κB precursors, namely, via the degradation of NF-κB1/p105. Our recent report (27) was the first to demonstrate that a viral protein can bind and stabilize NF-κB1/p105 to counteract upstream signals induced by TNF. The augmentation of NF-κB1/p105 stability through binding to other cellular proteins, such as arrestin-2, G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 5, and EP4 receptor-associated protein (EPRAP), was also previously demonstrated (26, 30). Interestingly, both arrestin-2 and EPRAP were shown to directly bind to the COOH-terminal domain of p105 (26, 30). Moreover, it was previously shown that the interaction of EPRAP with the p105 C terminus, which contains conserved target sequences for the IKK complex Pro-Glu-Ser-Thr-rich domain, contributes crucially to EPRAP-mediated protection against p105 phosphorylation and degradation (26). Given that our previous results demonstrated that CPXV-006 and other members of this class of ANK repeat-containing proteins bind to the C terminus of p105 (27), we hypothesize that such binding physically blocks the phosphorylation of the C terminus of NF-κB1/p105 by the IKK complex, a prerequisite for NF-κB1/p105 degradation.

In conclusion, using a targeted gene knockout approach, we present evidence that CPXV-006 plays a significant role in the IKK-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of NF-κB1/p105 in myeloid cells such as macrophages. The effect of this protein on NF-κB1/p105 is reflected downstream of the pathway, particularly on virus-induced NF-κB-regulated proinflammatory cytokine induction from virus-infected macrophages. Moreover, we demonstrate that the deletion of this CPXV-006 ANK repeat protein from CPXV significantly hinders the ability of the virus to prevent the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response in vivo, particularly in the lungs. Finally, data presented in this study demonstrate that members of this ANK repeat family are essential elements in the strategy used specifically by pathogenic orthopoxviruses to evade the early innate immune responses by repressing the NF-κB signaling pathway in response to virus infection.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the University of Florida College of Medicine and by a development grant from the Southeast Regional Center of Excellence for Emerging Infections and Biodefense.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira, S., S. Uematsu, and O. Takeuchi. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124:783-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxby, D., and M. Bennett. 1997. Cowpox: a re-evaluation of the risks of human cowpox based on new epidemiological information. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 13:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beinke, S., and S. C. Ley. 2004. Functions of NF-kappaB1 and NF-kappaB2 in immune cell biology. Biochem. J. 382:393-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutler, B. 2005. The Toll-like receptors: analysis by forward genetic methods. Immunogenetics 57:385-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billings, B., S. A. Smith, Z. Zhang, D. K. Lahiri, and G. J. Kotwal. 2004. Lack of N1L gene expression results in a significant decrease of vaccinia virus replication in mouse brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1030:297-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakrabarti, S., J. R. Sisler, and B. Moss. 1997. Compact, synthetic, vaccinia virus early/late promoter for protein expression. BioTechniques 23:1094-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, S. J., J. C. Hsiao, S. Sonnberg, C. T. Chiang, M. H. Yang, D. L. Tzou, A. A. Mercer, and W. Chang. 2009. Poxvirus host range protein CP77 contains an F-box-like domain that is necessary to suppress NF-κB activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha but is independent of its host range function. J. Virol. 83:4140-4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chantrey, J., H. Meyer, D. Baxby, M. Begon, K. J. Bown, S. M. Hazel, T. Jones, W. I. Montgomery, and M. Bennett. 1999. Cowpox: reservoir hosts and geographic range. Epidemiol. Infect. 122:455-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crouch, A. C., D. Baxby, C. M. McCracken, R. M. Gaskell, and M. Bennett. 1995. Serological evidence for the reservoir hosts of cowpox virus in British wildlife. Epidemiol. Infect. 115:185-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earl, P. L., N. Cooper, L. S. Wyatt, B. Moss, and M. W. Carroll. 1998. Preparation of cell cultures and vaccinia virus stocks, p. 16.16.1-16.16.3. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology, vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finlay, B. B., and G. McFadden. 2006. Anti-immunology: evasion of the host immune system by bacterial and viral pathogens. Cell 124:767-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman, J. M., and M. S. Horwitz. 2002. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced NF-κB activation by the adenovirus E3-10.4/14.5K complex. J. Virol. 76:5515-5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gedey, R., X. L. Jin, O. Hinthong, and J. L. Shisler. 2006. Poxviral regulation of the host NF-κB response: the vaccinia virus M2L protein inhibits induction of NF-κB activation via an ERK2 pathway in virus-infected human embryonic kidney cells. J. Virol. 80:8676-8685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh, S., and M. S. Hayden. 2008. New regulators of NF-kappaB in inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:837-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh, S., M. J. May, and E. B. Kopp. 1998. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:225-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goff, A., N. Twenhafel, A. Garrison, E. Mucker, J. Lawler, and J. Paragas. 2007. In vivo imaging of cidofovir treatment of cowpox virus infection. Virus Res. 128:88-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harte, M. T., I. R. Haga, G. Maloney, P. Gray, P. C. Reading, N. W. Bartlett, G. L. Smith, A. Bowie, and L. A. O'Neill. 2003. The poxvirus protein A52R targets Toll-like receptor signaling complexes to suppress host defense. J. Exp. Med. 197:343-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawranek, T., M. Tritscher, W. H. Muss, J. Jecel, N. Nowotny, J. Kolodziejek, M. Emberger, H. Schaeppi, and H. Hintner. 2003. Feline orthopoxvirus infection transmitted from cat to human. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 49:513-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayden, M. S., and S. Ghosh. 2008. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell 132:344-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiscott, J., H. Kwon, and P. Genin. 2001. Hostile takeovers: viral appropriation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 107:143-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston, J. B., G. Wang, J. W. Barrett, S. H. Nazarian, K. Colwill, M. Moran, and G. McFadden. 2005. Myxoma virus M-T5 protects infected cells from the stress of cell cycle arrest through its interaction with host cell cullin-1. J. Virol. 79:10750-10763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keck, J. G., C. J. Baldick, Jr., and B. Moss. 1990. Role of DNA replication in vaccinia virus gene expression: a naked template is required for transcription of three late trans-activator genes. Cell 61:801-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacNeill, A. L., L. L. Moldawer, and R. W. Moyer. 2009. The role of the cowpox virus crmA gene during intratracheal and intradermal infection of C57BL/6 mice. Virology 384:151-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manes, N. P., R. D. Estep, H. M. Mottaz, R. J. Moore, T. R. Clauss, M. E. Monroe, X. Du, J. N. Adkins, S. W. Wong, and R. D. Smith. 2008. Comparative proteomics of human monkeypox and vaccinia intracellular mature and extracellular enveloped virions. J. Proteome Res. 7:960-968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minami, M., K. Shimizu, Y. Okamoto, E. Folco, M. L. Ilasaca, M. W. Feinberg, M. Aikawa, and P. Libby. 2008. Prostaglandin E receptor type 4-associated protein interacts directly with NF-kappaB1 and attenuates macrophage activation. J. Biol. Chem. 283:9692-9703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohamed, M. R., M. M. Rahman, J. S. Lanchbury, D. Shattuck, C. Neff, M. Dufford, N. van Buuren, K. Fagan, M. Barry, S. Smith, I. Damon, and G. McFadden. 2009. Proteomic screening of variola virus reveals a unique NF-kappaB inhibitor that is highly conserved among pathogenic orthopoxviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106:9045-9050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moss, B. 2007. Poxviridiae: the viruses and their replication, p. 2905-2946. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 29.Oie, K. L., and D. J. Pickup. 2001. Cowpox virus and other members of the orthopoxvirus genus interfere with the regulation of NF-kappaB activation. Virology 288:175-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parameswaran, N., C. S. Pao, K. S. Leonhard, D. S. Kang, M. Kratz, S. C. Ley, and J. L. Benovic. 2006. Arrestin-2 and G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 interact with NFkappaB1 p105 and negatively regulate lipopolysaccharide-stimulated ERK1/2 activation in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 281:34159-34170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pelkonen, P. M., K. Tarvainen, A. Hynninen, E. R. Kallio, K. Henttonen, A. Palva, A. Vaheri, and O. Vapalahti. 2003. Cowpox with severe generalized eruption, Finland. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1458-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santoro, M. G., A. Rossi, and C. Amici. 2003. NF-kappaB and virus infection: who controls whom. EMBO J. 22:2552-2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schupp, P., M. Pfeffer, H. Meyer, G. Burck, K. Kolmel, and C. Neumann. 2001. Cowpox virus in a 12-year-old boy: rapid identification by an orthopoxvirus-specific polymerase chain reaction. Br. J. Dermatol. 145:146-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sen, R., and D. Baltimore. 1986. Multiple nuclear factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell 46:705-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shisler, J. L., and X. L. Jin. 2004. The vaccinia virus K1L gene product inhibits host NF-κB activation by preventing IκBα degradation. J. Virol. 78:3553-3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonnberg, S., B. T. Seet, T. Pawson, S. B. Fleming, and A. A. Mercer. 2008. Poxvirus ankyrin repeat proteins are a unique class of F-box proteins that associate with cellular SCF1 ubiquitin ligase complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:10955-10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stack, J., I. R. Haga, M. Schroder, N. W. Bartlett, G. Maloney, P. C. Reading, K. A. Fitzgerald, G. L. Smith, and A. G. Bowie. 2005. Vaccinia virus protein A46R targets multiple Toll-like-interleukin-1 receptor adaptors and contributes to virulence. J. Exp. Med. 201:1007-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Buuren, N., B. Couturier, Y. Xiong, and M. Barry. 2008. Ectromelia virus encodes a novel family of F-box proteins that interact with the SCF complex. J. Virol. 82:9917-9927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, G., J. W. Barrett, M. Stanford, S. J. Werden, J. B. Johnston, X. Gao, M. Sun, J. Q. Cheng, and G. McFadden. 2006. Infection of human cancer cells with myxoma virus requires Akt activation via interaction with a viral ankyrin-repeat host range factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:4640-4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]