Abstract

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) particles bear a receptor-binding site located in the pre-S1 domain of the large HBV envelope protein. Using the hepatitis delta virus (HDV) as a surrogate of HBV, a second infectivity determinant was recently identified in the envelope proteins antigenic loop (AGL), and its activity was shown to depend upon cysteine residues that are essential for the structure of the HBV immunodominant “a” determinant. Here, an alanine-scanning mutagenesis approach was used to precisely map the AGL infectivity determinant to a set of conserved residues, which are predicted to cluster together with cysteines in the AGL disulfide bridges network. Several substitutions suppressed both infectivity and the “a” determinant, whereas others were infectivity deficient with only a partial impact on antigenicity. Interestingly, G145R, a substitution often arising under immune pressure selection and detrimental to the “a” determinant, had no effect on infectivity. Altogether, these findings indicate that the AGL infectivity determinant is closely related to, yet separable from, the “a” determinant. Finally, a selection of HDV entry-deficient mutations were introduced at the surface of HBV virions and shown to also abrogate infection in the HBV model. Therefore, a function can at last be assigned to the orphan “a” determinant, the first-discovered marker of HBV infection. The characterization of the AGL functions at viral entry may lead to novel approaches in the development of antivirals against HBV.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) causes acute and chronic infections in humans; such infections are often associated with severe liver diseases, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (10). To date, it is estimated that approximately 350 millions individuals worldwide suffer from chronic infection despite the availability of an effective vaccine for more than 25 years. Remarkably, the development of a vaccine soon after the HBV discovery was, at least in part, the consequence of a very peculiar feature that is unique to members of the Hepadnaviridae family: viral envelope proteins are produced in quantities far exceeding the amounts required for assembly of HBV virions (6) and, owing to their capacity for autoassembly, the vast majority are secreted as subviral particles. Besides the practical consequences in the original vaccine development, in nature, the phenomenon of HBV envelope protein overexpression has provided a helper function to the hepatitis delta virus (HDV) (29). The HBV envelope proteins assist in packaging the HDV ribonucleoprotein (RNP) in case of HBV-HDV coinfection, thereby ensuring spreading of the satellite HDV. As a result, the coats of HBV and HDV particles are similar, consisting of cell-derived lipids and the HBV envelope proteins—large, middle, and small—bearing the HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and referred to as L-HBsAg, M-HBsAg, and S-HBsAg, respectively (4, 14).

The HBsAg includes an immunodominant determinant common to all HBV strains, referred to as “a,” and several mutually exclusive subtype-specific determinants referred to as “d”/“y” and “w”/“r” (21). The “a” determinant is defined by a specific conformation of the antigenic loop (AGL) polypeptide present at the surface of subviral, HBV, or HDV particles. The AGL itself resides between the transmembrane domain II (residues 80 to 100) and the hydrophobic carboxyl terminus (residues 165 to 226) of the envelope proteins S domain (see Fig. 1). It is the “a” determinant that elicits the most effective neutralizing antibody response upon vaccination or infection (32). Surprisingly, a function in the HBV life cycle had never been assigned to the “a” determinant, the first identified HBV marker, until the recent demonstration of its involvement in HDV entry (2, 15). More precisely, it was shown that the AGL cysteine residues were critical for both the structure of the “a” determinant and HDV infectivity (2).

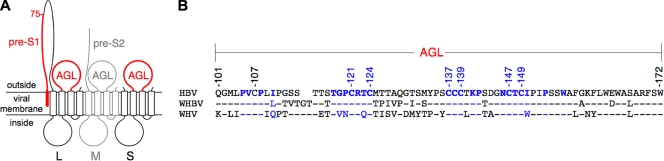

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the HBV envelope protein AGL. (A) The topology of the L-, M-, and S-HBsAg proteins (L, M, and S, respectively) is represented. The determinants of viral entry, pre-S1 and AGL, are indicated in red. The M-HBsAg protein, represented in gray, is dispensable for infectivity. Open boxes represent transmembrane regions in the S domain. (B) Alignment of the AGL amino acids sequences (positions 101 to 172 in the S domain) of HBV (genotype D, ayw3 phenotype), WMHBV, and WHV. The GenBank sequence numbers of the isolates are as follows: J02203 (HBV), AY226578 (WMHBV), and NC_004107 (WHV). HBV amino acid residues important for infectivity (the present study) are indicated in blue. A hyphen denotes amino acid identity with the HBV sequence.

It is now well established that both HBV and HDV entry rely on the pre-S1 domain of L-HBsAg as the primary infectivity determinant that is likely to promote attachment to a specific receptor at the surface of human hepatocytes (11). The AGL determinant could thus fulfill complementary functions for attachment, uptake, or particle disassembly after entry (2, 15).

In the present study, the AGL infectivity determinant was mapped and confirmed to be closely related to the “a” determinant. Moreover, its essential function at viral entry was demonstrated in the HBV model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of HDV and HBV particles.

Huh-7 cells were transfected with a mixture of pSVLD3 plasmid for the production of HDV RNPs, and pT7HB2.7, or its derivatives, for the supply of the wild-type (wt) or mutant HBV envelope proteins, respectively (2). AGL mutations were either introduced directly in pT7HB2.7 by site-directed mutagenesis as described previously (2) or after cloning of chemically synthesized mutant HBV DNA fragments (Genecust Europe, Luxembourg). All mutant plasmids were proof sequenced before use for transfection. Transfections were carried out by use of the FuGENE 6 reagent (Roche) as described previously (3). Culture medium harvested posttransfection was analyzed for the presence of viral particles by immunoblotting for detection of HBV envelope proteins and by Northern blotting for detection of HDV RNA (3). For the production of HBV particles, the plasmid pCIHBenv(−) for the expression of HBV nucleocapsid was substituted for pSVLD3 (3). Culture medium harvested posttransfection was analyzed for envelope proteins by immunoblotting and for HBV DNA by Southern blot hybridization as described previously (3).

In vitro infection assays.

HepaRG cell cultures were conducted as described previously (3, 12). For infection with HDV virions, clarified Huh-7 supernatants containing wt or mutant virions were used as inocula after normalization of their HDV RNA titers. HepaRG cells (3.3 × 105 cells/20-mm-diameter well) were exposed to 108 genome equivalents (ge) of HDV virions for 16 h in the presence of 5% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 (Sigma). Cells were harvested at day 7 postinoculation and tested for the presence of genomic HDV RNA as a marker of infection. For infection with HBV virions, clarified supernatants were concentrated by precipitation with PEG as described previously (2), and HepaRG cells (3.3 × 105 cells/20-mm-diameter well) were exposed to HBV virions at a multiplicity of 50 ge per cell for 16 h in the presence of 5% PEG. Cells were harvested at day 14 postinoculation, and purified mRNA was analyzed by Northern blot hybridization for the presence of HBV mRNA. In addition, culture medium from HepaRG cells harvested at day 14 postinoculation with HBV was monitored for the presence of HBe antigen (HBeAg) by using the ETI-EBK Plus immunoassay from Dia-Sorin.

Specific antigenicity.

A pre-S2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was developed to calibrate the preparation of viral particles for their content in HBV envelope proteins prior to being subjected to ELISA specific for the “a” determinant. Antibodies used in the “pre-S2 ELISA” are specific for a linear epitope in the pre-S2 domain of the L- and M-HBsAg proteins; their reactivity with the viral particles is therefore unaltered by the AGL mutations. Briefly, each well of a 96-well Maxisorp plate (Nunc) was coated with viral particles by adding 2.5 μl per well of clarified supernatant from transfected cells in 100 μl of 50 mM NaHCO3 buffer (pH 9.6). Plates were incubated overnight at room temperature and then blocked for 1 h at 37°C with 300 μl of 50 mM NaHCO3 buffer (pH 9.6)/well containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). After blocking, the plates were washed three times with 300 μl/well of 0.1% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBST; pH 7.2). Detection of bound viral particles was achieved by adding 100 μl/well of a 1/1,000 dilution of rabbit anti-pre-S2 antibody (R257) in PBST-10% FBS, followed by incubation at 37°C for 2 h. The plates were washed three times with 200 μl of PBST/well. Then, 100 μl/well of a 1/2,000 dilution of HRP-labeled anti-rabbit antibody in PBST-10% FBS was added, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After five washes with 200 μl of PBST/well, 100 μl of Ultra TMB HRP substrate (Pierce)/well was added, followed by incubation at room temperature for 15 min. The color reaction was stopped with sulfuric acid. The optical density was measured at 450 nm with an ELISA plate reader. To test the effect of AGL mutations on the “a” determinant, pre-S2-normalized samples were subjected to two commercial immunoassays (Monolisa HBsAg Ultra [Bio-Rad] and ETI-MAK-4 HBsAg [Dia-Sorin]) according to the manufacturers' recommendations. These assays utilize monoclonal antibodies directed to epitopes of the “a” determinant.

RESULTS

HBV entry into human hepatocytes depends upon two elements of the viral envelope proteins (Fig. 1): (i) the N-terminal 75 amino acid residues of the L-HBsAg pre-S1 domain (it is assumed to bear a receptor-binding domain) (11) and (ii) the AGL of one or both of the L-HBsAg and S-HBsAg proteins in which cysteine residues 121, 124, 137, 138, 139, 147, and 149 play a crucial role (2).

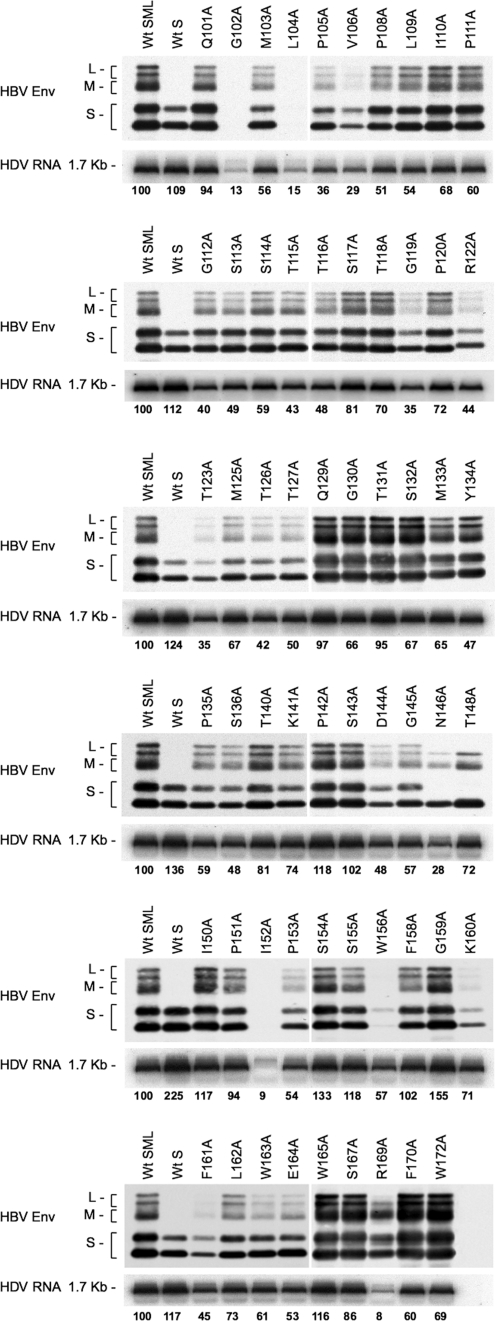

Alanine substitutions for noncysteine residues in the AGL sequence are permissive for HDV particles secretion.

To fully map the AGL infectivity determinant, we generated HBV envelope protein mutants bearing a substitution of alanine for each of the noncysteine residues in the AGL sequence (positions 101 to 172 of the S domain). The capacity of each mutant for HDV particles secretion was monitored after cotransfection of Huh-7 cells with the mutant expression plasmid and a plasmid for expression of the HDV RNP (2). All mutants—with the exception of G102A, L104A, and I152A—were competent for the production and release of HDV virions in the culture medium, as shown in Fig. 2. The variations in envelope proteins secretion between mutants paralleled those recorded for viral RNA, indicating that the ratio of subviral particles to virions was not affected by the mutations. Two mutants, V106A and W156A, were impaired for stability or secretion, but at levels that were still compatible with production of HDV. Note that the N146A and T148A substitutions remove the signal for N glycosylation at position 146, leading to the detection of S- and L-HBsAg as unglycosylated forms only (M-HBsAg is detected as a glycosylated form bearing N- and O-linked carbohydrates in the pre-S2 domain). Mutant R169 was not considered for subsequent infectivity assay because the mutation appeared to prevent L-HBsAg protein expression (Fig. 2). We thus concluded that alanine could substitute for most of the noncysteine AGL residues without severely affecting secretion of subviral and HDV particles, suggesting that the high level of the AGL sequence conservation across HBV genotypes is not related to a function in morphogenesis. The selected HDV mutants were thus amenable to in vitro infection assays.

FIG. 2.

Production of HDV particles coated with HBV envelope proteins bearing substitutions in the AGL amino acid sequence. Culture fluids from Huh-7 cells were harvested after transfection with a mixture of pSVLD3 coding for HDV RNPs and pT7HB2.7, or derivatives, coding for wt or HBV envelope protein mutants, respectively. Particles from 1 ml of culture fluids were concentrated and assayed for the presence of HBV envelope proteins by immunoblotting (HBV Env). Note that detection of HBV envelope proteins was achieved by using a rabbit anti-S antibody (R247) that recognizes a linear epitope in the cytosolic domain-I of the three envelope proteins and a rabbit anti-pre-S2 antibody for specific detection of L- and M-HBsAg proteins. The relative levels of the immunoblotting signals for HBV envelope proteins thus do not reflect the real ratio of L-/M-/S-HBsAg. Particles from 140 μl of culture medium were assayed for the presence of genomic HDV RNA by Northern blot hybridization. The size in kilobases of genomic HDV RNA is indicated. Wt SML, HDV particles coated with wt S-, M-, and L-HBsAg; Wt S, HDV particles coated with wt S-HBsAg. S, M, and L indicate the positions of the S-, M-, and L-HBsAg, respectively.

Noncysteine residues of the AGL infectivity determinant are predicted to cluster together with cysteines in the AGL disulfide bonds network.

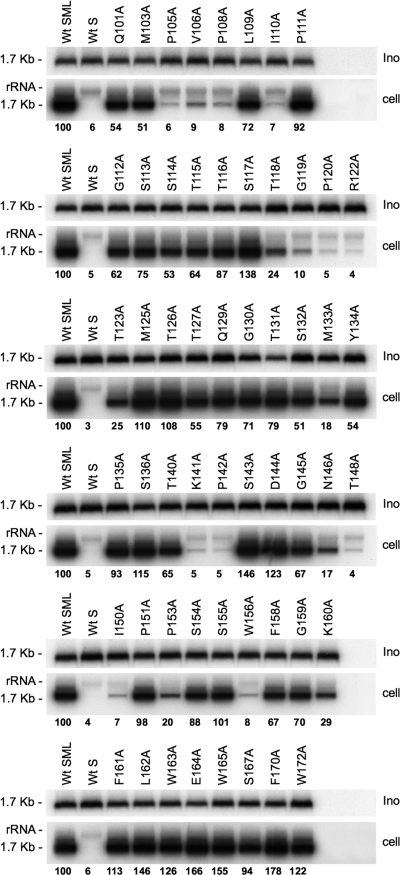

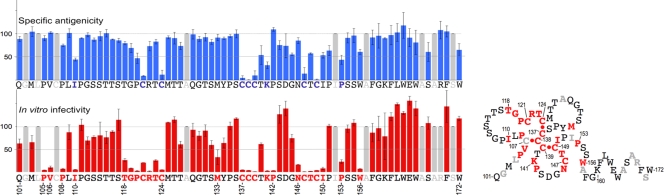

For infectivity analysis, each preparation of mutant HDV was normalized to ∼108 ge/ml prior to inoculation to 3.3 × 105 HepaRG cells (3, 12). Normalization was controlled by measuring the levels of HDV RNA in the inocula recovered after the 16 h virus-cell exposure (Fig. 3). The fact that viral RNA was detected at equivalent levels in all samples was an indication that alanine substitutions did not destabilize the viral envelope. Seven days postinoculation, cells were assayed for intracellular HDV RNA as evidence of infection (Fig. 3). Most of the alanine substitutions were tolerant of infectivity. In contrast, substitutions for P105, V106, P108, I110, G119, P120, R122, K141, P142, N146, T148, I150, P153, and W156 reduced infectivity to <25% of that of the wt. We interpret the loss of infectivity for N146A and T148A mutants as resulting from the amino acid substitution and not from the lack of N-linked carbohydrates at position 146 since, in a recent analysis, a nonglycosylated N146T HDV mutant was infectious in primary cultures of human hepatocytes (28). The histogram in Fig. 4 indicates infectivity values for each mutant in percentage relative to that of the wt. By combining these results with those of our previous study on AGL cysteine function (2), the AGL infectivity determinant appears to consist of cysteines 121 to 149; prolines 105, 108, 120, 142, and 153; positively charged residues R122 and K141; hydrophobic residues at positions 106, 110, 133, 150, and 156; uncharged polar residues (N146, T118, T123, and T148); and G119 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Infectivity of HDV particles coated with HBV envelope proteins bearing amino acid substitutions in the AGL. The results of infection assays are based on Northern blot analysis of HDV RNA extracted from HepaRG cells exposed to wt or mutant HDV particles. In this experiment, 3.3 × 105 cells were exposed to ∼108 ge of HDV particles. Inocula (Ino) were recovered after a 16-h exposure to HepaRG cells, and their HDV RNA content was controlled by Northern blot hybridization using a genomic strand-specific, 32P-labeled RNA probe. Signals are from 0.5 ml of inoculum. Cellular RNA extracted from 105 cells (cell) harvested at day 7 postinoculation was analyzed for the presence of HDV RNA. Signals were quantified by using a Phosphorimager. The size in kilobases of HDV RNA is indicated. Wt SML, HDV particles coated with wt S-, M-, and L-HBsAg; Wt S, HDV particles coated with wt S-HBsAg.

FIG. 4.

Specific antigenicity and in vitro infectivity of HDV particles bearing amino acid substitutions in the AGL. In the upper left portion of the figure is a histogram showing the effect of mutation of each AGL amino acid (from Q101 to W172) on specific antigenicity, and in the lower left is a histogram for infectivity. Values are given as percentage relative to that of the wt. Mutations are substitutions of serine for cysteine residues (2) or alanine for noncysteine residues. Specific antigenicity was defined as the ratio of the mean values of two commercial HBsAg assays (Monolisa HBsAg Ultra ELISA kit [Bio-Rad] and ETI-MAK-4 HBsAg [Dia-Sorin]) divided by pre-S2 ELISA values. The pre-S2 ELISA was used to normalize preparations of viral particles for their content in HBV envelope proteins prior to being subjected to ELISA specific for the “a” determinant. Gray bars indicate amino acid residues that have not been tested. Error bars indicate the standard deviation for three independent assays. On the right is a hypothetical representation of the AGL secondary structure. Putative disulfide bridges are represented (red dots). Residues essential for the infectivity determinant are indicated in red. They are predicted to cluster together in an AGL disulfide bridges network similar to the one represented here. Note that this clustering would occur, regardless of the arrangements of inter- and intramolecular disulfide bonds. According to Mangold et al. (20), C121 and C147 are likely to be involved in intermolecular cross-linking; this would also have a clustering effect. Amino acids that have not been tested are indicated in gray.

The AGL infectivity determinant is closely related to the immunodominant “a” determinant.

It was previously shown that the reactivity of AGL-cysteine mutants with conformation-sensitive anti-HBsAg antibodies was drastically affected (2, 20). This was indicative of the “a” determinant's dependence upon a precise network of AGL disulfide bonds. Here, the alanine substitutions for noncysteine residues were examined for their impact on antigenicity. After normalization for envelope proteins using an anti-pre-S2 ELISA, the antigenicity of each mutant was measured in two commercial immunoassays (Monolisa HBsAg Ultra and ETI-MAK-4 HBsAg). Specific antigenicity was then defined as the ratio of the mean value obtained by using the two commercial HBsAg ELISA tests divided by the value obtained with the pre-S2 ELISA after normalization (2). The results presented in Fig. 4 indicate percentages of the mutant's reactivity relative to that of the wt. Included in the histogram are values obtained for C121S, C124S, C137S, C138S, C139S, C147S, and C149S in a previous study (2). When infectivity and antigenicity are used as criteria for the mutants characterization, three phenotypes can be distinguished: (i) the wt phenotype displaying alteration of neither infectivity nor the “a” determinant; (ii) the infectivity-deficient phenotype that conserves the “a” determinant (i.e., P105A, V106A, P108A, T118A, G119A, R122A, T123A, P142A, N146A, T148A, I150A, and W156A); and (iii) the phenotype deficient for both the “a” determinant and infectivity: I110A, P120A, K141A, and P153A.

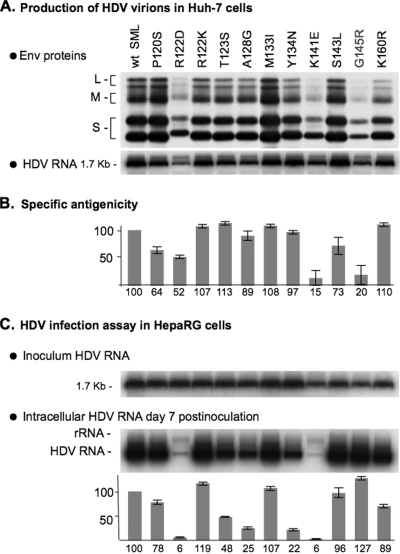

The G145R substitution alters the “a” determinant but preserves HDV infectivity.

To further characterize the AGL function, a selection of “natural” mutations the AGL amino acid sequence was tested. Natural variations in the AGL sequence are the consequence of genetic heterogeneity; HBV DNA sequences are classified into eight genotypes that diverge from each other by at least 8%. Mutations in the AGL sequence are also found in “escape mutants” as the result of a selection pressure exerted by vaccination, immunotherapy, or antiviral therapy. Escape mutants are able to grow in the presence of anti-HBsAg antibodies and may escape detection by immunoassays for HBsAg. Three types of substitutions were chosen: (i) two (R122K and K160R) correspond to the natural genetic heterogeneity; (ii) seven (P120S, T123S, M133I, Y134N, S143L, K141E, and G145R) are mutants described in the literature as HBV “variants” (7); and (iii) two additional mutants, R122D and A128G. G145R is the most common of the HBV variants; it was shown to appear in individuals who received HBV vaccine or had been treated with anti-HBsAg immunoglobulin, and to be horizontally transmitted. As expected, all of these envelope protein mutants were competent for secretion of HDV particles (Fig. 5). With regard to specific antigenicity, the two naturally occurring escape mutations K141E (16) and G145R (33) had the highest impact on the “a” determinant. However, while the G145R change had no effect at viral entry, K141E reduced infectivity to 6% of that of the wt HDV. The antigenicity and infectivity of the R122K and K160R mutants, corresponding to the “adw” and “ayr” HBsAg subtypes, respectively, were not affected, as expected. The remaining substitutions (P120S, R122D, T123S, A128G, M133I, Y134N, and S143L) did not affect recognition of the “a” determinant by monoclonal antibodies but altered infectivity to various degrees. R122D was the most deleterious, reducing infectivity to 6% of that of the wt. Altogether, these findings indicate that the “a” determinant and the AGL infectivity determinant are closely related; however, they do not perfectly match, as shown by the phenotypes of G145R or Y134N.

FIG. 5.

Effect of “natural” AGL mutations on HDV infectivity. The production of wt and mutant HDV particles was achieved by transfection of Huh-7 cells with pSVLD3 and pT7HB2.7 or its derivative plasmids. (A) Particles from 1 ml of culture fluids were assayed for the presence of HBV envelope proteins and HDV RNA as described in the legend to Fig. 2. (B) Histogram showing the specific antigenicity for each mutant, expressed as the percentage relative to the wt. Specific antigenicity was defined as in the legend to Fig. 4. Error bars indicate the standard deviation for three independent assays. (C) Prior to infection assays, supernatants were normalized to ∼108 ge/ml. A 1-ml portion of normalized inoculum was added to 3.3 × 105 HepaRG cells. At day 7 postinoculation, HepaRG cells were harvested, and cellular RNA was analyzed by Northern blot hybridization with 32P-labeled RNA probes specific for HDV RNA. Signals are from 6.6 × 104 cells. Quantification of HDV RNA signals by using a phosphorimager is indicated in the histogram as percentages of the wt value. The size in kilobases of HDV RNA is indicated. Wt SML, HDV particles coated with wt S-, M-, and L-HBsAg. S, M, and L indicate the positions of the S-, M-, and L-HBsAg, respectively.

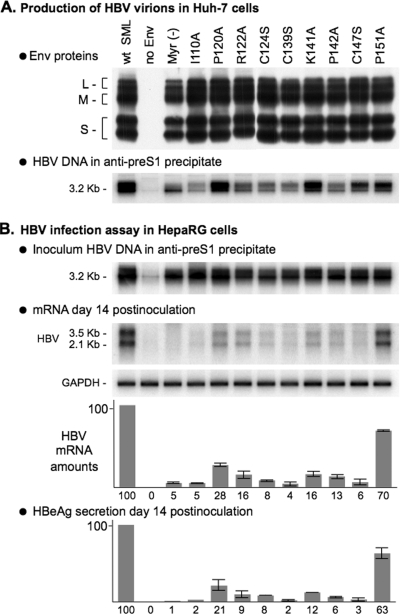

The AGL is a determinant of HBV infectivity.

Finally, to directly assess the function of the AGL in the HBV life cycle, we produced recombinant HBV virions bearing AGL amino acid substitutions. They were selected among the most deleterious to HDV infectivity: (i) serine substitutions for cysteines 124, 139, and 147, and (ii) alanine substitutions for either prolines 120 and 142, positively charged residues R122 and K141, or the hydrophobic residue I110. We also selected P151A a mutation that was tolerant of HDV infectivity (Fig. 3). In addition, HBV particles bearing a nonmyristoylated L-HBsAg were produced as noninfectious control. Virion production was achieved in Huh-7 cells by cotransfection with pCIHBenv(−) and pT7HB2.7 or its derivatives, as described previously (3). They were assayed for viral envelope proteins by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting and for HBV DNA after immunocapture with anti-preS1 antibodies (3). Virion-containing samples were then normalized to approximately 1.5 × 107 ge/ml. A 1-ml portion of this inoculum was then applied to 3.3 × 105 HepaRG cells, as described previously (3). Both cells and culture medium were harvested at day 14 postinoculation for the detection of de novo-synthesized HBV mRNA and HBeAg as evidence of infection. As shown in Fig. 6, viral mRNA and HBeAg were detected in cultures exposed to wt- or P151A-HBV virions. In contrast, according to both HBV mRNA and HBeAg assays, I110A, P120A, R122A, C124S, C139S, K141A, P124A, and C147S were detrimental to HBV infectivity. Note that some of these mutations (I110A, C139S, and C147S) were as inhibitory as the pre-S1 G2A substitution that prevents L-HBsAg myristoylation (1). These data thus demonstrate that the AGL sequence bears an essential determinant of HBV infectivity.

FIG. 6.

In vitro infectivity of HBV particles bearing amino acid substitutions in the AGL. The production of wt and mutant HBV particles was achieved by transfection of Huh-7 cells with a mixture of pCIHBenv(−) coding for HBV nucleocapsid and pT7HB2.7 or derivatives, coding for wt or HBV envelope protein mutants, respectively. (A) Culture fluids (1 ml) of transfected cells were assayed for the presence of HBV envelope proteins by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis. HBV virions were immunoprecipitated from the culture fluids of transfected cells using anti-pre-S1 antibodies, and viral DNA was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization. (B) HepaRG cells (3.3 × 105 cells) were inoculated with 1 ml of inoculum containing normalized amounts of HBV virions corresponding to approximately 1.5 × 107 ge. Cells were harvested at day 14 postinoculation, and mRNAs were purified and assayed by Northern blot analysis using 32P-labeled RNA probes for detection of HBV or GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) mRNAs. Signals are from 1.1 × 105 cells. Histograms show the amounts of intracellular HBV mRNA or extracellular HBeAg from HepaRG cultures at day 14 postinoculation. The infectivity of each HBV mutant is expressed as a percentage of that of the wt HBV, according to both the Northern blot analysis for detection of HBV mRNA normalized to GAPDH mRNA and the HBeAg ELISA. Wt SML, HBV particles coated with wt S-, M-, and L-HBsAg (S, M, and L, respectively). Error bars indicate the standard deviation for three independent infection assays. The sizes in kilobases of HBV mRNAs are indicated.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that the AGL bears a conformation-dependent determinant of HBV entry consisting of cysteine residues 121 to 149 and P105, V106, P108, I110, T118, G119, P120, R122, T123, K141, P142, T148, I150, and W156. Using genetic and biochemical approaches, we had previously shown in the HDV model a close relationship between infectivity and the “a” determinant, both being dependent upon a precise network of disulfide bonds established by the AGL cysteine residues (2). This was the first indication of an essential function underlying the conservation of the “a” determinant among all HBV genotypes. Here, this correlation is further demonstrated by the identification of several alanine substitutions for noncysteine AGL residues, which also have the capacity to suppress both the “a” and the infectivity determinants. However, a few substitutions, chief among them G145R (33), altered the “a” determinant without suppressing infectivity. The fact that the “a” and infectivity determinants do not perfectly match should not come as a surprise considering that the correctly folded AGL may include residues essential for infectivity, which are not accessible to antibodies (e.g., P105, V106, P108, T118, P142, and N146) and, conversely, it may bear surface-exposed residues that are not directly engaged in the entry process. In addition, some of the exposed residues might be conserved because their DNA coding sequence also encodes, in the minus-one frame, an essential motif of the viral polymerase.

An explanation for the G145R phenotype would be that glycine at position 145 belong to, or be in the spatial vicinity of, all epitopes of the “a” determinant. In that case, introducing a large, positively charged side chain at position 145 could prevent antibody binding without affecting the overall AGL conformation. It is worth noting that the G145A mutation does not lead to a loss of the “a” determinant (Fig. 4), indicating that the positive charge at position 145 is likely responsible for the loss of antigenicity. The two positively charged R122 and K141 residues essential for infectivity could eventually mediate attachment to negatively charged molecules such as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). Recently, HBV infection has been shown to require an initial attachment to GAGs, which was described as dependent on the L-HBsAg protein, although the direct contribution of the pre-S domain of L-HBsAg in GAG-binding was not demonstrated (18, 23), leaving the possibility that the GAG-binding site is located in the AGL (8). In this context, some mutations in the AGL sequence (i.e., cysteine or proline substitutions) could lead to a loss of infectivity by masking R122 and K141. The G145R mutation could act in such a way, but the introduction of Arg at position 145 would compensate for the loss of surface-exposed R122 or K141 and, thereby, restore infectivity.

It is important to note that AGL cysteines play the most important role for both antigenicity and infectivity. As indicated above, cysteines could be engaged in disulfide bonds to stabilize the viral envelope, the disassembly of which, at viral entry, would then require isomerization of the disulfide bridges. Interestingly, most of the noncysteine amino acids identified here as essential for entry (i.e., P105, V106, P108, I110, T118, G119, P120, R122, T123, K141, P142, T148, I150, and P153) lie in the vicinity of cysteines on the linear AGL sequence (Fig. 4). These residues may constitute a conformation-dependent motif by clustering together with cysteines in the disulfide bond network. Since there is no crystallography data available on the AGL structure, the assignment of disulfide bonds to specific cysteine residues is based on mutational analysis (19, 20) and reactivity of circular AGL-specific peptides with monoclonal antibodies directed to the “a” determinant (5, 31). According to a recent three-dimensional modeling of S-HBsAg, the mutual distances between the alpha-carbon atoms of cysteine residues in the “a” determinant, with the exception of C147, are predicted to be within a range of 4 to 8 Å, which is compatible with disulfide bond formation (30). The function of such a motif may then reside in binding directly to a cell ligand, in assisting the proper exposure (or conformation) of the pre-S1 determinant (24), or in the disulfide bond isomerization that is presumably necessary for envelope disassembly (2). Note that the structure represented in Fig. 4 is hypothetical; it does not take into account, for instance, the intermolecular bridges that are known to exist. It is meant to illustrate the phenomenon of clustering in the AGL disulfide bonds network to create an infectivity-competent motif, regardless of the exact arrangement of the disulfide bonds.

In retrospect, the association of the “a” determinant to a crucial function at viral entry was clearly suggested by the observation that anti-HBsAg antibodies (mostly directed to the “a” determinant) usually display a potent neutralizing activity, an indication that they could neutralize not only by aggregating viral particles but also by blocking a functional motif borne by the “a” determinant. This would also explain the high efficiency of the HBV vaccine that includes only HBsAg (i.e., without pre-S1 or pre-S2 antigens) (27, 32). Thus, anti-HBsAg, like anti-preS1 antibodies, would directly interfere with entry. In fact, we found that monoclonal antibodies specific for “a” were at least as efficient as anti-pre-S1 monoclonal antibodies in neutralizing infection in vitro (25). The efficiency of anti- HBsAg antibodies may also result from their capacity to interfere with more than one event at viral entry: by preventing binding to a cell receptor as suggested above and by creating a blockade to disulfide bond isomerization. The multiple functions of the AGL infectivity determinant may thus represent as many targets for new antiviral strategies.

Interestingly, the AGL infectivity determinant has been mapped here to residues that are conserved in the sequences of all human HBV genotypes (Fig. 1), but also in that of the woolly monkey hepatitis B virus (WMHBV) (17) and, to a lesser extent, the woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) (9). This observation strongly suggests that the AGL determinant is not species specific (13).

Our findings should also lead to a reinterpretation of the significance of naturally occurring mutations in the “a” determinant. Such mutations can arise after anti-HBV immunoglobulin therapy or under the pressure of the immune response in infected or vaccinated individuals (7, 26). Mutations in the “a” determinant may allow the virus to escape diagnosis, vaccination, or immunotherapy. As shown here, they may also affect infectivity and, hence, the potential of a given escape mutant for propagation. Consider, for instance, the case of G145R and K141E: both are known to lack the “a” determinant but only G145R retains full infectivity in vitro (in fact, G145R was found more infectious that wt by 27% [see Fig. 5]). The in vitro phenotype of G145R is thus in agreement with its well documented characteristics in vivo: (i) it is the most frequently reported escape mutant, (ii) it appears stable over time, and (iii) it can be horizontally transmitted. G145R has thus the potential to cause a significant public health problem in countries where vaccination programs have been implemented; it is reassuring, however, that two recombinant hepatitis B vaccines were shown to fully protect chimpanzees against infection with G154R (22). In contrast, K141E would be predicted to have very limited potential for propagation in vivo, since its infectivity in vitro is reduced to 6% of that of the wt (Fig. 5).

Finally, our HDV-based infection assay could prove useful for predicting the potential of naturally occurring mutations in the “a” determinant for propagation in the population of vaccinated individuals. The model is also adapted to evaluate the capacity of vaccine-induced antibodies to neutralize HBV variants.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge C. Trépo and O. Hantz for providing the HepaRG cell line.

This study was supported through grants from ANRS and INTS. C.S. is a CNRS investigator. J.S. is the recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from ANRS.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 July 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abou-Jaoude, G., S. Molina, P. Maurel, and C. Sureau. 2007. Myristoylation signal transfer from the large to the middle or the small HBV envelope protein leads to a loss of HDV particles infectivity. Virology 365:204-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abou-Jaoude, G., and C. Sureau. 2007. Entry of hepatitis delta virus requires the conserved cysteine residues of the hepatitis B virus envelope protein antigenic loop and is blocked by inhibitors of thiol-disulfide exchange. J. Virol. 81:13057-13066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanchet, M., and C. Sureau. 2007. Infectivity determinants of the hepatitis B virus pre-S domain are confined to the N-terminal 75 amino acid residues. J. Virol. 81:5841-5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonino, F., K. H. Heermann, M. Rizzetto, and W. H. Gerlich. 1986. Hepatitis delta virus: protein composition of delta antigen and its hepatitis B virus-derived envelope. J. Virol. 58:945-950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, S. E., C. R. Howard, A. J. Zuckerman, and M. W. Steward. 1984. Affinity of antibody responses in man to hepatitis B vaccine determined with synthetic peptides. Lancet ii:184-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruss, V. 2007. Hepatitis B virus morphogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 13:65-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carman, W. F. 1997. The clinical significance of surface antigen variants of hepatitis B virus. J. Viral Hepat. 4(Suppl. 1):11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chai, N., H. E. Chang, E. Nicolas, Z. Han, M. Jarnik, and J. Taylor. 2008. Properties of subviral particles of hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 82:7812-7817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen, J. I., R. H. Miller, B. Rosenblum, K. Denniston, J. L. Gerin, and R. H. Purcell. 1988. Sequence comparison of woodchuck hepatitis virus replicative forms shows conservation of the genome. Virology 162:12-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganem, D., and A. M. Prince. 2004. Hepatitis B virus infection: natural history and clinical consequences. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:1118-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glebe, D., and S. Urban. 2007. Viral and cellular determinants involved in hepadnaviral entry. World J. Gastroenterol. 13:22-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gripon, P., S. Rumin, S. Urban, J. Le Seyec, D. Glaise, I. Cannie, C. Guyomard, J. Lucas, C. Trepo, and C. Guguen-Guillouzo. 2002. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:15655-15660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gudima, S., Y. He, N. Chai, V. Bruss, S. Urban, W. Mason, and J. Taylor. 2008. Primary human hepatocytes are susceptible to infection by hepatitis delta virus assembled with envelope proteins of woodchuck hepatitis virus. J. Virol. 82:7276-7283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heermann, K. H., and W. H. Gerlich. 1991. Surface proteins of hepatitis B viruses, p. 109-144. In A. Maclachlan (ed.), Molecular biology of hepatitis B virus. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 15.Jaoude, G. A., and C. Sureau. 2005. Role of the antigenic loop of the hepatitis B virus envelope proteins in infectivity of hepatitis delta virus. J. Virol. 79:10460-10466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karthigesu, V. D., L. M. Allison, M. Fortuin, M. Mendy, H. C. Whittle, and C. R. Howard. 1994. A novel hepatitis B virus variant in the sera of immunized children. J. Gen. Virol. 75(Pt. 2):443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanford, R. E., D. Chavez, K. M. Brasky, R. B. Burns III, and R. Rico-Hesse. 1998. Isolation of a hepadnavirus from the woolly monkey, a New World primate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5757-5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leistner, C. M., S. Gruen-Bernhard, and D. Glebe. 2008. Role of glycosaminoglycans for binding and infection of hepatitis B virus. Cell Microbiol. 10:122-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangold, C. M., and R. E. Streeck. 1993. Mutational analysis of the cysteine residues in the hepatitis B virus small envelope protein. J. Virol. 67:4588-4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangold, C. M., F. Unckell, M. Werr, and R. E. Streeck. 1995. Secretion and antigenicity of hepatitis B virus small envelope proteins lacking cysteines in the major antigenic region. Virology 211:535-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norder, H., A. M. Courouce, P. Coursaget, J. M. Echevarria, S. D. Lee, I. K. Mushahwar, B. H. Robertson, S. Locarnini, and L. O. Magnius. 2004. Genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus strains derived worldwide: genotypes, subgenotypes, and HBsAg subtypes. Intervirology 47:289-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogata, N., P. J. Cote, A. R. Zanetti, R. H. Miller, M. Shapiro, J. Gerin, and R. H. Purcell. 1999. Licensed recombinant hepatitis B vaccines protect chimpanzees against infection with the prototype surface gene mutant of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 30:779-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulze, A., P. Gripon, and S. Urban. 2007. Hepatitis B virus infection initiates with a large surface protein-dependent binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Hepatology 46:1759-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seitz, S., S. Urban, C. Antoni, and B. Bottcher. 2007. Cryo-electron microscopy of hepatitis B virions reveals variability in envelope capsid interactions. EMBO J. 26:4160-4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shearer, M. H., C. Sureau, B. Dunbar, and R. C. Kennedy. 1998. Structural characterization of viral neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen. Mol. Immunol. 35:1149-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheldon, J., and V. Soriano. 2008. Hepatitis B virus escape mutants induced by antiviral therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:766-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shepard, C. W., E. P. Simard, L. Finelli, A. E. Fiore, and B. P. Bell. 2006. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiol. Rev. 28:112-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sureau, C., C. Fournier-Wirth, and P. Maurel. 2003. Role of N glycosylation of hepatitis B virus envelope proteins in morphogenesis and infectivity of hepatitis delta virus. J. Virol. 77:5519-5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor, J. M. 2006. Hepatitis delta virus. Virology 344:71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Hemert, F. J., H. L. Zaaijer, B. Berkhout, and V. V. Lukashov. 2008. Mosaic amino acid conservation in 3D structures of surface protein and polymerase of hepatitis B virus. Virology 370:362-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waters, J. A., S. E. Brown, M. W. Steward, C. R. Howard, and H. C. Thomas. 1992. Analysis of the antigenic epitopes of hepatitis B surface antigen involved in the induction of a protective antibody response. Virus Res. 22:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zanetti, A. R., P. Van Damme, and D. Shouval. 2008. The global impact of vaccination against hepatitis B: a historical overview. Vaccine 26:6266-6273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuckerman, A. J., T. J. Harrison, and C. J. Oon. 1994. Mutations in S region of hepatitis B virus. Lancet 343:737-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]