Abstract

Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia is an aggressive myeloproliferative disorder characterized by malignant transformation in the hematopoietic stem cell compartment with proliferation of differentiated progeny. Seventy-five percent of patients harbor mutations in the NF1, NRAS, KRAS, or PTPN11 genes, which encode components of Ras signaling networks. Using single nucleotide polymorphism arrays, we identified a region of 11q isodisomy that contains the CBL gene in several JMML samples, and subsequently identified CBL mutations in 27 of 159 JMML samples. Thirteen of these mutations alter codon Y371. In this report, we also demonstrate that CBL and RAS/PTPN11 mutations were mutually exclusive in these patients. Moreover, the exclusivity of CBL mutations with respect to other Ras pathway-associated mutations indicates that CBL may have a role in deregulating this key pathway in JMML.

Introduction

Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) is an aggressive clonal myeloproliferative disorder (MPD) of young children.1,2 Extensive molecular data implicate deregulated Ras signaling as a key initiating event in JMML, with 60% of patients harboring somatic PTPN11, NRAS, or KRAS mutations and another 10% to 15% of cases arising in children with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and/or showing somatic inactivation of the NF1 tumor suppressor gene.3,4 Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) shares clinical and laboratory features with JMML, including a high frequency of RAS mutations and a hypersensitive pattern of granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming unit growth (CFU-GM) in response to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF).5–8 Moreover, phosphoflow cytometric analysis of CD38dim/CD14+/CD33+ cells from JMML and CMML patients recently demonstrated a distinctive pattern of STAT5 hyperphosphorylation in response to low doses of GM-CSF.9

Advances in detecting DNA copy number alterations and acquired uniparental isodisomy (UPD) with single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays have proven fruitful for discovering mutations in other hematologic malignancies.10,11 To determine whether regions of copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (LOH) indicative of acquired UPD existed in JMML, we performed Affymetrix SNP 6.0 array analysis on samples from 27 JMML patients with and without known PTPN11, RAS, or NF1 abnormalities. We identified a region of 11q UPD in 5 of these cases, which includes the CBL gene. Importantly, recent reports uncovered acquired 11q copy-neutral LOH in related MPDs, and molecular analysis identified CBL mutations in these cases.10,11 Furthermore, a few CBL mutations had been reported previously in myeloid malignancies.12–14 Based on these observations, we investigated CBL in these 5 JMML patients with 11q copy-neutral LOH and detected homozygous mutations in all cases. We then sequenced diagnostic samples from 154 additional JMML patients assembled from a large international cohort and identified 22 more with CBL mutations. We also analyzed a series of 44 patients with CMML who were treated at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center for mutations and detected several lesions in CBL.

Methods

Patient samples and DNA extraction

All patients or their guardians provided informed consent for these studies according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by institutional review committees at each participating center. CMML patients were diagnosed and treated at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Genomic DNA was isolated using PureGene reagents (QIAGEN). A clinical history of NF1 was available for some, but not all, patients. DNA from 40 anonymous, normal controls was also analyzed.

SNP array analysis

A total of 500 ng sample DNA was analyzed using Affymetrix 6.0 SNP arrays as previously described.15–17 Extraction and summarization of SNP/CNV probe hybridization intensities from CEL files were performed in dChip,18 and normalization was performed using a “reference normalization” algorithm that uses only probes from chromosomes known or predicted to be diploid to guide array normalization.19 Additional details on the bioinformatic and statistical analyses are included in supplemental data (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Mutational screening, progenitor colony, and phosphoflow studies

All JMML and CMML patients had mutational screening for PTPN11, NRAS, and KRAS performed as previously described.20–22 Polymerase chain reaction amplification of CBL exons 8 and 9 was performed using primers and conditions listed in supplemental Table 1. Polymerase chain reaction products were visualized, purified, and sequenced according to standard methodologies. CFU-GM colonies were grown according to previously published methods.23

Table 1.

CBL mutations detected in 27 JMML patients

| Location | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | No. of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intron 7 | 1096–1G>C* | Splice site | 1 |

| Exon 8 | 1111T>C* | 371 Tyr>His | 10 |

| 1111T>G* | 371 Tyr>Asp | 2 | |

| 1112A>G* | 371 Tyr>Cys | 1 | |

| 1139T>C* | 380 Leu>Pro | 1 | |

| 1141T>C* | 381 Cys>Arg | 1 | |

| 1150T>C* | 384 Cys>Arg | 4 | |

| 1186T>C* | 396 Cys>Arg | 1 | |

| 1190 del99bp | Deletion | 1 | |

| 1210 T>C* | 404 Cys>Arg | 1 | |

| 1222 T>C* | 408 Trp>Arg | 1 | |

| Intron 8 | 1227+4C>T | Splice site | 1 |

| 1228–2A>G* | Splice site | 1 | |

| Exon 9 | 1244G>T* | 415 Gly>Val | 1 |

Homozygous mutation.

Statistical methods

The χ2 test was used to examine the statistical significance of a relationship between categorical variables. Because a normal distribution cannot be assumed, median values and ranges were reported and nonparametric statistics were used to test for differences in continuous variables for different subgroups (Kruskal-Wallis test with subsequent posthoc Mann-Whitney U test). All P values were 2-sided, and values < .05 were considered statistically significant. P values > .1 were reported as nonsignificant, whereas those between 0.05 and 0.1 were reported in detail. No adjustment of the α-level to account for multiple testing was performed because of the explorative nature of the statistical analysis and the limited patient numbers available with clinical data.

Results and discussion

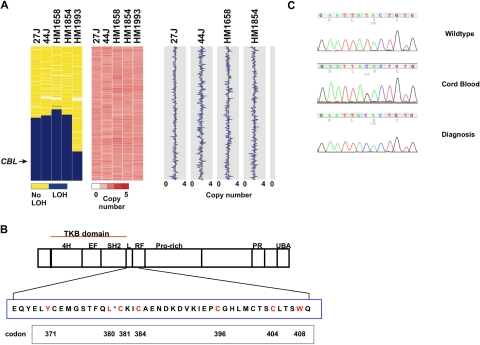

We analyzed 27 JMML samples enriched for patients without known Ras pathway mutations for regions of copy-neutral LOH and detected 11q UPD in 5 cases (Figure 1A, supplemental Figure 1). Based on recent reports of CBL mutations in patients with other myeloid malignancies, we sequenced exons 8 and 9 of CBL in 26 of 27 of the patients who had SNP arrays performed (there was 1 patient without DNA available for sequencing, but this patient did not exhibit 11q UPD) and in an additional 133 JMML samples.10–14 CBL sequencing data revealed 25 homozygous and 2 heterozygous mutations (Figure 1C; Table 1) located throughout the linker and RING finger domain, with the predominantly affected codon in JMML being the tyrosine residue at position 371 (Y371; Figure 1C; Table 1). No mutations were identified in 40 normal controls.

Figure 1.

Identification of acquired isodisomy of 11q in JMML and CBL mutations. (A) Chromosome 11 loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) data and copy number heatmaps and plots are shown for 5 representative patients with homozygous CBL mutations, and demonstrate acquired copy-neutral LOH involving CBL for each patient. The region of LOH (blue) in HM1993 is smaller than in the other cases shown but contains the CBL locus. The copy number heatmap generated by dChip is shown where pink represents a diploid copy number, whereas areas of white and red represent loss and gain, respectively. The absence of white and red supports a copy neutral event. This is also represented in the panel on the right where a diploid copy number is represented by the red vertical line, whereas gains and losses are traced in blue; no copy number alterations on chromosome 11 were identified, indicating copy-neutral LOH. (B) Schematic of CBL with expansion of codons in exon 8. Highlighted in red are the residues in exon 8 where missense mutations were identified in JMML and CMML. *Boundary of the linker and RING finger domains. Listed below are the codon numbers. (C) Representative electropherograms from a normal control, the heterozygous mutation from the cord blood sample of HM1854, and the homozygous mutation at diagnosis.

One patient who was diagnosed at 7 months of age (HM1854) had an umbilical cord blood sample available for genotyping (Figure 1C). Interestingly, DNA isolated from mononuclear cells at diagnosis demonstrated a homozygous Y371H, whereas DNA isolated from her cord blood demonstrated a heterozygous mutation (Figure 1C). Similarly, SNP analysis of the diagnostic sample revealed 11q isodisomy which was absent in the cord blood sample (supplemental Figure 1). DNA extracted from hypersensitive CFU-GM colonies plucked from cells propagated at diagnosis revealed that 10 of 16 colonies harbored homozygous lesions, whereas 6 were heterozygous. Furthermore, an aliquot of cord blood was defrosted and plated on complete methylcellulose, and a spectrum of colony-forming unit–granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte/macrophage, megakaryocyte and CFU-GM colonies were genotyped, with almost all colonies demonstrating the heterozygous CBL mutation.

In a second patient (HM1658), an Epstein-Barr virus–transformed cell line also harbored the identical homozygous Y371H alteration seen in DNA from diagnosis. However, previous data suggest that B cells are only rarely involved in the JMML clone.24 Hypersensitive CFU-GM colonies picked at diagnosis were largely homozygous for the CBL mutation (9 of 13 tested), but the rest were heterozygous. Finally, in a third patient (HM1993), DNA isolated from the buccal mucosa demonstrated a heterozygous lesion, whereas the majority of CFU-GM colonies again demonstrated homozygous mutations. Together, these data support the hypothesis that reduplication of an inherited CBL mutation in a pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell confers a selective advantage for the homozygous state and also raise the possibility of germline lesions in some patients with CBL mutations.

Consistent with other reports, we also detected CBL mutations in 5 of 44 CMML samples (supplemental Table 2).10,11 None of the specimens in this cohort with a RAS mutation (n = 15) also had a CBL mutation. However, 1 CMML patient had a mutation in both JAK2 (V617F) and CBL. In contrast to JMML, we and others found no Y371 alterations in CMML.10,11

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with CBL, PTPN11, RAS, or no mutation

| Clinical characteristic | CBL | PTPN11 | RAS | No mutation | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 1.1 (0.1-3.6) | 2.8 (0.4-5.7) | 1.2 (0.01-6.0) | 2.6 (0.1-12.2) | .09 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male, n (%) | 12 (63) | 12 (60) | 18 (82) | 16 (76) | |

| Female, n (%) | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | NS |

| WBC, ×106/L | |||||

| Less than 50 000, n (%) | 15 (79) | 15 (75) | 13 (62) | 16 (76) | |

| More than or equal to 50 000, n (%) | 4 (21) | 5 (25) | 8 (38) | 5 (24) | NS |

| Median monocytes, ×106/L (range) | 5320 (1380-38 840) | 6040 (1690-20 390) | 5040 (1030-28 350) | 3140 (1170-50 100) | NS |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | |||||

| Less than 8.0 g/dL, n (%) | 5 (26) | 3 (15) | 6 (29) | 6 (29) | |

| More than 8.0 g/dL, n (%) | 14 (74) | 17 (85) | 15 (71) | 15 (71) | NS |

| Platelets, ×109/L | |||||

| Less than 50, n (%) | 10 (53) | 11 (58) | 7 (33) | 5 (24) | |

| More than or equal to 50, n (%) | 9 (47) | 8 (42) | 14 (67) | 16 (76) | .10 |

| Hemoglobin F | |||||

| Normal for age, n (%) | 6 (55) | 3 (20) | 6 (40) | 4 (33) | |

| Elevated for age, n (%) | 5 (45) | 12 (80) | 9 (60) | 8 (67) | NS |

| Unknown, n | 8 | 5 | 7 | 9 | |

| Bone marrow cytogenetics | |||||

| Normal, n (%) | 15 (94) | 11 (65) | 15 (75) | 12 (60) | |

| Monosomy 7, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (18) | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | NS |

| Other, n (%) | 1 (6) | 3 (18) | 2 (10) | 4 (20) | |

| Unknown, n | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| Liver size | |||||

| Normal, n (%) | 2 (12) | 5 (29) | 2 (11) | 5 (24) | |

| Moderate (1-3 cm), n (%) | 2 (12) | 4 (24) | 6 (33) | 10 (48) | |

| Massive (≥ 4 cm), n (%) | 13 (77) | 8 (47) | 10 (56) | 6 (29) | .09 |

| Unknown, n | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | |

| Spleen size | |||||

| Normal, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (19) | |

| Moderate (1-5 cm), n (%) | 4 (27) | 9 (53) | 8 (42) | 10 (48) | |

| Massive (≥ 6 cm), n (%) | 11 (73) | 7 (41) | 11 (58) | 7 (33) | .07 |

| Unknown, n | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Clinical status | |||||

| Alive, n (%) | 11 (58) | 15 (79) | 12 (55) | 15 (71) | |

| Dead, n (%) | 8 (42) | 4 (21) | 9 (43) | 6 (29) | NS |

| Unknown, n | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

NS indicates not significant.

We specifically assessed the frequency of CBL mutations in a subset of 68 JMML cases without mutations in RAS or PTPN11. Forty-five of these patients had no clinical evidence of NF1, and the NF1 status was unknown in the other 23. We identified 27 CBL mutations (39.7%). These data demonstrate CBL mutations in 10% to 15% of JMML patients overall, which is similar to the frequency of NF1 mutations. Importantly, we did not detect any CBL mutations in 91 JMML samples with known mutations in RAS or PTPN11. The difference in the frequency of CBL mutations in JMML patients without mutations in either RAS, PTPN11, or NF1 (27 of 68) versus those with a known RAS or PTPN11 mutation (0 of 91) was highly significant (Fisher exact test, P < .001).

We also compared the clinical features at diagnosis of patients with CBL mutations vs those with an RAS, PTPN11, or no known mutation (Table 2) and found that there was a tendency for CBL-mutated patients to present at a younger age (P = .09), although this was not statistically significant. Interestingly, there were no cases of monosomy 7 in the CBL group; however, this was also not statistically significant. Although there were also no significant differences in overall survival among the mutation groups, our sample size is not sufficiently large enough to detect modest differences. Future prospective analyses of genotype/phenotype correlations will therefore be necessary to extend these findings.

In previous studies of phospho-signaling networks in JMML, we evaluated 10 specimens from patients with known KRAS, NRAS, PTPN11, or NF1 mutations and 4 without a known Ras pathway lesion.9 DNA sequence analysis revealed CBL mutations in 3 of these 4 patients. These 3 cases exhibited a similar pattern of CFU-GM hypersensitivity in methylcellulose cultures and expressed high levels of pSTAT5 in response to low doses of GM-CSF, similar to other JMML patients with somatic mutations in RAS/PTPN11 or NF1 (the 3 cases with CBL mutations are HM1661, 1854, and 1993).10

c-Cbl primarily functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and is responsible for the intracellular transport and degradation of a large number of receptor tyrosine kinases but also retains important adaptor functions.25,26 Approximately 150 proteins associate with or are regulated by c-Cbl.25 Among these proteins is Grb2, an adaptor molecule that binds to c-Cbl and prevents it from binding to SOS, a known guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras.27 CBL mutations reported in myeloid malignancies uniformly affect either the linker region or the RING finger domain.10,12–14 Loss of ubiquitination of activated receptor tyrosine kinases is thought to contribute to the transforming potential of leukemia-associated mutant Cbl proteins.14 Mutations that affect Y371 are rare in acute myeloid leukemia28; however, expressing this mutant Cbl protein with Flt3 in BaF3 cells induced cytokine-independent growth and survival. Mutations in Y368 or Y371 could confer substantial structural changes to the TKB domain that could ultimately affect binding partners with different consequences.29 For example, Y371F abolishes E3 ligase activity, whereas substitution to glutamic acid confers constitutive activation.30,31 In addition, Y371 mediates binding of c-Cbl to the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3 kinase,32 and the Y371F abolishes this interaction.

The identification of homozygous CBL mutations in JMML suggests that CBL is a new tumor suppressor gene. Cells from these patients display identical GM-CSF hypersensitivity and pSTAT5 signaling as other known Ras pathway mutations. Moreover, the known molecular genetic and biochemical features of JMML and our data showing that CBL, PTPN11, KRAS, and NRAS are mutually exclusive imply that leukemia-associated CBL mutations result in hyperactive Ras. These effects of c-Cbl could be mediated by failure of the mutant protein to efficiently target one or more cytokine receptors for degradation by ubiquitination by an alternative biochemical mechanism. Along these lines, it is of interest that Y371 is a “hot spot” for CBL mutations in JMML—that it is rarely mutated in other myeloid malignancies, and that the majority of the mutations detected are missense substitutions or in-frame deletions resulting in a translated protein that may retain some function. Further work will be necessary to unravel the biochemical effects of these mutants on Ras networks and on other growth control pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the referring physicians and patients/families who contributed samples to this work, the National Children's Cancer Foundation for facilitating the submission of some of the JMML samples, and all the investigators in the EWOG-MDS.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA113557, M.L.L.; CA108631, M.L.L., K.M.S., L.C.; CA104282, M.L.L., K.M.S.; CA72614, K.M.S.; CA95621, M.L.L., M.K., P.D.E., K.M.S.), California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (T1-00002; D.S.S.), V Foundation for Cancer Research (M.L.L., K.M.S.), the Frank A. Campini Foundation (M.L.L., K.M.S.), LLS 6059-09 (M.L.L.), the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (C.G.M.), the Deutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung (C.M.N., C.F.), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG KR 3473/1-1; C.F.), and the Deutsche José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung (DJCLS R 08/19; C.F.). M.L.L. is a Clinical Scholar of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of America.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.L.L., D.S,S., C.F., and C.M.N. developed the study and hypotheses; M.L.L. directed D.S.S., M.K., S.A., and L.C. in clinical sample collection and subsequent research at University of California, San Francisco; C.F. and M.F. organized the sample collection and sequence analysis in Germany on behalf of EWOG-MDS; C.G.M. performed the SNP array analysis; E.B., C.E.B.-R., P.D.E., H.H., J.-P.I., M.M.v.d.H.-E., F.L., J.S., M.T., M.W., and M.Z. contributed samples; and M.L.L., K.M.S., and C.M.N. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mignon L. Loh, 513 Parnassus Ave, HSE-302, Box 0519, San Francisco, CA 94143; e-mail: lohm@peds.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Emanuel PD. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Curr Hematol Rep. 2004;3:203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauchle JO, Braun BS, Loh ML, Shannon K. Inherited predispositions and hyperactive Ras in myeloid leukemogenesis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:579–585. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flotho C, Kratz C, Niemeyer CM. Targeting RAS signaling pathways in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:715–725. doi: 10.2174/138945007780830773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan RJ, Cooper T, Kratz CP, Weiss B, Loh ML. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: a report from the 2nd International JMML Symposium. Leuk Res. 2009;33:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emanuel PD. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:1335–1342. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onida F, Kantarjian HM, Smith TL, et al. Prognostic factors and scoring systems in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: a retrospective analysis of 213 patients. Blood. 2002;99:840–849. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cambier N, Baruchel A, Schlageter MH, et al. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: from biology to therapy. Hematol Cell Ther. 1997;39:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s00282-997-0041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emanuel PD, Bates LJ, Castleberry RP, Gualtieri RJ, Zuckerman KS. Selective hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor by juvenile chronic myeloid leukemia hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1991;77:925–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotecha N, Flores NJ, Irish JM, et al. Single-cell profiling identifies aberrant STAT5 activation in myeloid malignancies with specific clinical and biologic correlates. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunbar AJ, Gondek LP, O'Keefe CL, et al. 250K single nucleotide polymorphism array karyotyping identifies acquired uniparental disomy and homozygous mutations, including novel missense substitutions of c-Cbl, in myeloid malignancies. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10349–10357. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grand FH, Hidalgo-Curtis CE, Ernst T, et al. Frequent CBL mutations associated with 11q acquired uniparental disomy in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2009;113:6182–6192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbas S, Rotmans G, Lowenberg B, Valk PJ. Exon 8 splice site mutations in the gene encoding the E3-ligase CBL are associated with core binding factor acute myeloid leukemias. Haematologica. 2008;93:1595–1597. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caligiuri MA, Briesewitz R, Yu J, et al. Novel c-CBL and CBL-b ubiquitin ligase mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:1022–1024. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sargin B, Choudhary C, Crosetto N, et al. Flt3-dependent transformation by inactivating c-Cbl mutations in AML. Blood. 2007;110:1004–1012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullighan CG, Miller CB, Radtke I, et al. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of Ikaros. Nature. 2008;453:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature06866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flotho C, Steinemann D, Mullighan CG, et al. Genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia identifies uniparental disomy surrounding the NF1 locus in cases associated with neurofibromatosis but not in cases with mutant RAS or PTPN11. Oncogene. 2007;26:5816–5821. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin M, Wei LJ, Sellers WR, Lieberfarb M, Wong WH, Li C. dChipSNP: significance curve and clustering of SNP-array-based loss-of-heterozygosity data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1233–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pounds S, Cheng C, Mullighan C, Raimondi SC, Shurtleff S, Downing JR. Reference alignment of SNP microarray signals for copy number analysis of tumors. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:315–321. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalra R, Paderanga D, Olson K, Shannon KM. Genetic analysis is consistent with the hypothesis that NF1 limits myeloid cell growth through p21ras. Blood. 1994;84:3435–3439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loh ML, Vattikuti S, Schubbert S, et al. Mutations in PTPN11 implicate the SHP-2 phosphatase in leukemogenesis. Blood. 2004;103:2325–2331. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tartaglia M, Kalidas K, Shaw A, et al. PTPN11 mutations in Noonan syndrome: molecular spectrum, genotype-phenotype correlation, and phenotypic heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1555–1563. doi: 10.1086/340847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emanuel PD, Bates LJ, Zhu SW, Castleberry RP, Gualtieri RJ, Zuckerman KS. The role of monocyte-derived hemopoietic growth factors in the regulation of myeloproliferation in juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia. Exp Hematol. 1991;19:1017–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miles DK, Freedman MH, Stephens K, et al. Patterns of hematopoietic lineage involvement in children with neurofibromatosis type 1 and malignant myeloid disorders. Blood. 1996;88:4314–4320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt MH, Dikic I. The Cbl interactome and its functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:907–918. doi: 10.1038/nrm1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thien CB, Langdon WY. c-Cbl and Cbl-b ubiquitin ligases: substrate diversity and the negative regulation of signalling responses. Biochem J. 2005;391:153–166. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buday L, Khwaja A, Sipeki S, Farago A, Downward J. Interactions of Cbl with two adapter proteins, Grb2 and Crk, upon T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6159–6163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodrigues MS, Reddy MM, Walz C, et al. Novel Transforming Mutations of CBL in Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Vol. 112. San Francisco, CA: American Society of Hematology; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng N, Wang P, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Structure of a c-Cbl-UbcH7 complex: RING domain function in ubiquitin-protein ligases. Cell. 2000;102:533–539. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kassenbrock CK, Anderson SM. Regulation of ubiquitin protein ligase activity in c-Cbl by phosphorylation-induced conformational change and constitutive activation by tyrosine to glutamate point mutations. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28017–28027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levkowitz G, Waterman H, Ettenberg SA, et al. Ubiquitin ligase activity and tyrosine phosphorylation underlie suppression of growth factor signaling by c-Cbl/Sli-1. Mol Cell. 1999;4:1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Standaert ML, Sajan MP, Miura A, Bandyopadhyay G, Farese RV. Requirements for pYXXM motifs in Cbl for binding to the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Crk, and activation of atypical protein kinase C and glucose transport during insulin action in 3T3/L1 adipocytes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15494–15502. doi: 10.1021/bi049222q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.