Abstract

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder characterized by progressive destruction of insulin secreting β cells of the pancreas, in which CD8+ T cells play a critical role. The diversity in the HLA alleles expressed among various racial and ethnic groups leads to great variability in antigen presentation and recognition by CD8+ T cells in the context of MHC class I molecules. To date, studies aimed at identifying disease relevant antigenic epitopes have focused on using mice transgenic for HLA-A*0201, a common allele, particularly among Caucasians. We present HLA class I typing data from 88 type 1 diabetic children at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, where the patient population is ethnically diverse but largely minority. When categorized into the HLA supertypes A2, A3, B7, and C1, 77% of those studied belong to at least 1 supertype, and of these, 65% do not belong to the A2 supertype, which is the supertype represented by the HLA-A*0201 allele. These results support the need for studies using HLA transgenic mice expressing MHC molecules representative of a variety of HLA supertypes, particularly when searching for antigenic epitopes applicable for study among largely urban, minority pediatric populations.

Keywords: Type 1 Diabetes, Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA), Transgenic Mice

INTRODUCTION

There are over 14,000 new cases of type 1 diabetes diagnosed in the United States each year, the majority of which are in young children. Although the initiating factors underlying the autoimmunity causing this disease have not been elucidated, it is clear that T cells are involved from the very early phases of inflammation. Specifically, CD8+ T cells are vital to the development of disease, as evidenced by the lack of diabetes development in mouse models deficient in these T cells.1

Identification of disease relevant antigenic epitopes is critical for the development of trials aimed at establishing tolerance. Given the various limitations encountered in direct human investigations, HLA transgenic NOD mice expressing human class I MHC molecules serve as excellent animal models for study. In the case of HLA-A*0201, β cell peptides recognized by T cells in HLA transgenic NOD mice2 have recently been shown to also be targeted by T cells in type 1 diabetic patients.3 These findings have confirmed that islet specific antigens recognized by T cells and presented in the context of human MHC molecules in HLA transgenic NOD mice are highly relevant for studies in patients with type 1 diabetes. Therefore, knowledge of the HLA types of various populations is key in tailoring appropriate investigational and therapeutic trials. However, HLA class I alleles are tremendously diverse, with 489 HLA-A, 830 HLA-B, and 266 HLA-C alleles identified to date.4 Yet despite this large diversity, and the differences in gene expression among the various races and ethnic groups, most studies have focused solely on epitope identification using mice transgenic for HLA-A*0201. The allele frequency of HLA-A*0201 is nearly 50% among Caucasians in the U.S., but only 20% and 34% among African American and Hispanic individuals, respectively.5

We set out to characterize the HLA class I alleles present in a largely minority population of type 1 diabetic children at the Children's Hospital at Montefiore, and to evaluate whether investigations focusing on antigens discovered using HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice alone are sufficient for translational studies in this group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood samples from 88 children with type 1 diabetes treated at the Children's Hospital at Montefiore were collected. All of the children were thin, had acute onset of symptoms, and have required ongoing insulin therapy. Low-resolution typing of HLA-A, -B, and -C, followed by high-resolution typing of most of the HLA-A*02 alleles, was performed at the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh Histocompatibility Center under the direction of Dr. M. Trucco. Due to the use of primarily low-resolution typing, certain alleles had multiple potential identities. If only one of the potential alleles was considered common and well-documented (CWD) in the U.S.,4 the patient was assumed to be carrying this CWD allele. If more than one of the potential alleles was CWD, the allele was deemed not identifiable and was not used in subsequent analysis. Non-CWD alleles have extremely low frequencies and are unlikely to be found in a significant number of unrelated subjects.4 The identified alleles were then grouped as appropriate into the three well-characterized HLA-A or -B supertypes A2,6 A3,7 and B7,8 or the HLA-C supertype C1.9 HLA supertypes are designations aimed at grouping alleles that are known or predicted to bind similar antigenic peptides.6, 7 The HLA-C1 supertype was defined by bioinformatic methods rather than by peptide binding.9 For our analysis, we included within the C1 supertype only those alleles predicted to be members based on two separate bioinformatics strategies.

RESULTS

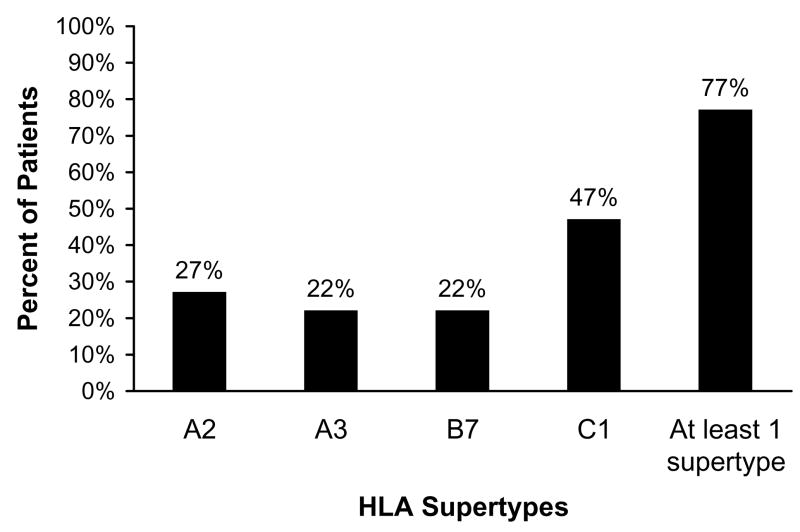

We identified 22 different HLA-A alleles, 45 different HLA-B alleles, and 17 different HLA-C alleles in our group of 88 children with type 1 diabetes. Although HLA-A*0201 was one of the most common alleles identified, only 16 of the 88 patients (18%) were positive for this allele. Of the 88 children, 27% (24) had an allele belonging to the HLA-A2 supertype (Fig. 1), of which HLA-A*0201 is a member. Twenty-two percent (19) had an allele belonging to the A3 supertype, 22% (19) an allele belonging to the B7 supertype, and 47% (41) an allele belonging to the C1 supertype. Seventy-seven percent of patients (68) belonged to at least 1 supertype, and 32% belonged to at least 2 supertypes. Of children belonging to at least 1 supertype, 65% (44) belonged to one other than A2, the supertype represented by the HLA-A*0201 transgenic mouse. Due to the limitations of low-resolution typing, 23% (43/176) of the HLA-A and HLA-B, and 47% (83/176) of the HLA-C alleles were not identifiable. As some of these alleles would have fallen into one of the four supertypes, our total of 77% belonging to at least one supertype is an underestimation. Thus, antigen-based diagnostic or therapeutic strategies that consider all four supertypes could potentially provide greater than 77% population coverage among our patients.

Figure 1.

Categorization of the HLA supertypes of 88 type 1 diabetic children from an urban children's hospital. The percent of children possessing an allele belonging to each of the class I supertypes A2, A3, B7, and C1 is shown. As indicated, 77% belong to at least one of these supertypes.

DISCUSSION

The pediatric population in the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore diabetes clinic is a diverse, largely urban group of approximately 400 diabetic children, 75–80% of whom are classified as type 1. Our study group, which was 51% Hispanic, 32% African American, 15% Caucasian, and 2% Asian, was representative of this diversity.

In our laboratory, we have identified disease relevant antigenic epitopes of insulin and IGRP using NOD mice transgenic for HLA-A*0201.2, 10 However, based on the results reported here, epitopes discovered using only HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice would exclude the 65% of diabetic children who fall into a supertype other than A2. In our population, and others with a similar demographic, studying alleles representative of other supertypes would make results much more applicable. For this reason, we have recently embarked on a similar antigen discovery program, but now using NOD mice transgenic for HLA-A*1101, HLA-B*0702, or HLA-Cw*0304. These alleles are representative of the HLA supertypes A3, B7, and C1, respectively. We have identified multiple antigenic epitopes in these mice (Z. Antal, J. C. Baker, P. Santamaria, T. P. DiLorenzo, unpublished data), and are in the process of testing for reactivity to these epitopes in our diabetic patients having alleles that are members of the corresponding HLA supertypes. Given the results presented here, our findings will be highly relevant to our group of diabetic children, as well as others having similar HLA representation.

In summary, in a population of type 1 diabetic children with a demographic similar to that at the Children's Hospital at Montefiore, the identification of MHC class I restricted antigenic epitopes should involve studies of HLA alleles belonging to multiple class I supertypes, given the great diversity and percentage of children belonging to supertypes other than A2. Furthermore, although close to 50% of Caucasians express an allele belonging to the A2 supertype, greater coverage of even a Caucasian population will be obtained if multiple supertypes are considered.7

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK77500, DK64315, and DK52956 to T.P.D.

References

- 1.Serreze DV, et al. Major histocompatibility complex class I-deficient NOD-B2mnull mice are diabetes and insulitis resistant. Diabetes. 1994;43:505–509. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takaki T, et al. HLA-A*0201-restricted T cells from humanized NOD mice recognize autoantigens of potential clinical relevance to type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2006;176:3257–3265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mallone R, et al. CD8+ T-cell responses identify β-cell autoimmunity in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:613–621. doi: 10.2337/db06-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cano P, et al. Common and well-documented HLA alleles: report of the ad-hoc committee of the American Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:392–417. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis JM, et al. Frequencies of HLA-A2 alleles in five U.S. population groups. Predominance of A*02011 and identification of HLA-A*0231. Hum Immunol. 2000;61:334–340. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(99)00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sette A, Sidney J. HLA supertypes and supermotifs: a functional perspective on HLA polymorphism. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:478–482. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidney J, et al. Practical, biochemical and evolutionary implications of the discovery of HLA class I supermotifs. Immunol Today. 1996;17:261–266. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sette A, Sidney J. Nine major HLA class I supertypes account for the vast preponderance of HLA-A and -B polymorphism. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s002510050594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doytchinova IA, Guan P, Flower DR. Identifiying human MHC supertypes using bioinformatic methods. J Immunol. 2004;172:4314–4323. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarchum I, et al. In vivo cytotoxicity of insulin-specific CD8+ T-cells in HLA-A*0201 transgenic NOD mice. Diabetes. 2007;56:2551–2560. doi: 10.2337/db07-0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]