Abstract

Cohesin complexes mediate sister chromatid cohesion. Cohesin also becomes enriched at DNA double-strand break sites and facilitates recombinational DNA repair. Here, we report that cohesin is essential for the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint. In contrast to cohesin's role in DNA repair, the checkpoint function of cohesin is independent of its ability to mediate cohesion. After RNAi-mediated depletion of cohesin, cells fail to properly activate the checkpoint kinase Chk2 and have defects in recruiting the mediator protein 53BP1 to DNA damage sites. Earlier work has shown that phosphorylation of the cohesin subunits Smc1 and Smc3 is required for the intra-S checkpoint, but Smc1/Smc3 are also subunits of a distinct recombination complex, RC-1. It was, therefore, unknown whether Smc1/Smc3 function in the intra-S checkpoint as part of cohesin. We show that Smc1/Smc3 are phosphorylated as part of cohesin and that cohesin is required for the intra-S checkpoint. We propose that accumulation of cohesin at DNA break sites is not only needed to mediate DNA repair, but also facilitates the recruitment of checkpoint proteins, which activate the intra-S and G2/M checkpoints.

Keywords: 53BP1, Chk2, Cohesin, DNA damage checkpoint, DNA double-strand break

Introduction

Cells are constantly challenged by exogenous and endogenous sources of DNA damage. Depending on the nature of the damage, cells activate different DNA repair mechanisms (for review, see Sancar et al, 2004). In parallel, cells also activate checkpoint pathways, which delay cell cycle progression until genome integrity has been restored (for review, see Shiloh, 2001). Depending on the cell cycle stage during which the DNA damage occurs, these surveillance mechanisms can arrest cells before initiation of DNA replication (G1/S checkpoint), during replication (intra-S phase checkpoint) or before entry into mitosis (G2/M checkpoint).

After DNA has been replicated, DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are preferentially repaired by homologous recombination. This mechanism uses a genetically identical DNA molecule, usually the sister chromatid, to faithfully repair damaged DNA and to ensure conservation of the original sequence information (for review, see Sancar et al, 2004). In budding yeast, efficient repair of DSBs by homologous recombination depends on cohesin, a multi-subunit chromosomal protein complex, which mediates cohesion between sister chromatids (Sjogren and Nasmyth, 2001; Schar et al, 2004; Strom and Sjogren, 2005; Strom et al, 2007; Unal et al, 2007). On formation of a DNA DSB, cohesin accumulates on chromatin in a 50 kb large domain that surrounds the break site and establishes novel cohesive structures throughout the whole genome. This ability of cohesin to establish cohesion de novo is essential for its role in DNA damage repair. These observations suggest that cohesin might facilitate recombinational repair by maintaining proximity between the broken sister chromatid and its intact counterpart, and possibly by physically stabilizing fragmented parts of the chromosome.

In vertebrates, sister chromatid cohesion is also mediated by cohesin, and depends, in addition, on a cohesin-associated protein called sororin. Sororin is required for the ability of cohesin to establish or maintain cohesion, but is dispensable for the association of cohesin with chromatin (Rankin et al, 2005; Schmitz et al, 2007). As in yeast, vertebrate cohesin is also required for efficient DNA damage repair and this function seems to depend on cohesin's ability to mediate sister chromatid cohesion (Sonoda et al., 2001; Potts et al., 2006; Schmitz et al., 2007; reviewed in Watrin and Peters, 2006; Strom and Sjogren, 2007). Furthermore, cohesin accumulates on chromatin on formation of DNA DSBs (Bekker-Jensen et al, 2006; Potts et al, 2006). However, in vertebrate cells, two proteins that can be part of cohesin are also known to have a role in the intra-S phase DNA damage checkpoint (Kim et al, 2002; Yazdi et al, 2002; Kitagawa et al, 2004; Luo et al, 2008). These proteins are large ATPases of the structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) protein family called Smc1 and Smc3. Smc1 is a substrate of the checkpoint protein kinase ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated), which phosphorylates two serine residues (S957, S966) in the large coiled-coil domain of Smc1 (Kim et al, 2002; Yazdi et al, 2002). Similar to several other DNA damage checkpoint proteins, Smc1 phosphorylated on S957 accumulates in irradiation-induced foci (IRIFs) in the cell nucleus, and mouse cells that express non-phosphorylatable mutants of Smc1 show defects in the intra-S phase checkpoint (Kim et al, 2002; Yazdi et al, 2002; Kitagawa et al, 2004). Similarly, two serine residues in the coiled-coil domain of Smc3 are also phosphorylated (Hauf et al, 2005; Luo et al, 2008), and ectopic expression of non-phosphorylatable Smc3 compromises the intra-S phase checkpoint (Luo et al, 2008).

Smc1 and Smc3 have been identified as subunits of two distinct protein complexes. Smc1 and Smc3 form heterodimers, which can assemble with two other proteins, Scc1/Rad21/Mcd1 and Scc3/SA, to form cohesin complexes, which are evolutionary conserved from yeast to men (Guacci et al, 1997; Michaelis et al, 1997; Losada et al, 1998; Sumara et al, 2000). In addition, mammalian Smc1 and Smc3 have been reported to be subunits of a distinct recombination complex, RC-1, which also contains DNA polymerase ɛ and DNA ligase III and functions in DNA repair (Jessberger et al, 1996; Stursberg et al, 1999).

It has, therefore, remained unknown whether DNA damage induces phosphorylation of Smc1 and Smc3 as part of cohesin, and if so, whether cohesin specifically functions in the intra-S phase checkpoint, or whether cohesin has a more general role in DNA damage checkpoints. To address these questions, we have depleted cohesin subunits and associated proteins from human cells by RNA interference (RNAi) and analysed DNA damage checkpoint responses in these cells. Our results indicate that Smc1 and Smc3 are phosphorylated in response to DNA damage as part of cohesin. We show that cohesin is not only required for the DNA damage-induced intra-S phase checkpoint, but also for the G2/M checkpoint, and that these functions are independent of cohesin's role in cohesion. Furthermore, we provide evidence that cohesin inactivation impairs recruitment of the DNA damage mediator protein 53BP1 to IRIFs and leads to defects in activation of the checkpoint kinase Chk2.

Results

Cohesin is required for the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint

We have recently shown that cohesin and the cohesin-interacting protein sororin are required for the repair of DNA damage during G2 phase in human-cultured cells (Schmitz et al, 2007). In these experiments, we had treated cells with caffeine, which inactivates the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint by inhibiting the kinases ATM and ATR (ATM and Rad3 related) and thus permits mitotic entry in the presence of DNA damage. This treatment had allowed us to score DNA damage by analysing the morphology of mitotic chromosomes, in which DNA breaks can easily be seen.

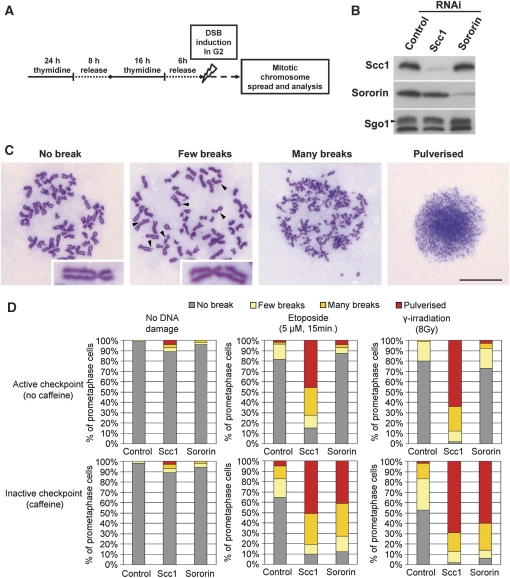

To address whether cohesin, in addition to its role in DNA damage repair, has a function in the G2/M checkpoint, we performed similar experiments in the absence of caffeine, that is under conditions in which the checkpoint can function normally. For this purpose, we synchronized HeLa cells in early S phase by double-thymidine treatment, released them for 6 h into G2 phase and induced the formation of DSBs by γ-irradiation or by treatment with the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide. Subsequently, cells were arrested in mitosis with the microtubule depolymerizing agent nocodazole and analysed by chromosome spreading and Giemsa staining (Figure 1A). In control populations, only relatively few mitotic cells (20%) contained broken chromosomes, and the extent of chromosome breaks in these cells was very small, indicating that the majority of cells had activated the G2/M checkpoint until most DSBs had been repaired. In contrast, after depletion of the cohesin subunits Scc1 or Smc3 by RNAi (Figure 1B; Supplementary Figure 1A), almost all mitotic cells contained broken chromosomes, most of which were highly fragmented (‘pulverized'; Figure 1C and D; Supplementary Figure 1B). Similar observations were made by immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) using antibodies to the single-strand DNA-binding protein RPA, which accumulates at DSBs. In these experiments, RPA antibodies stained only few control cells that had entered mitosis after irradiation in G2 phase (Supplementary Figure 2). In contrast, irradiated Scc1-depleted cells that had entered mitosis displayed multiple RPA foci, indicating that these cells had entered mitosis before DNA repair had been completed. These results indicate that Scc1- and Smc3-depleted cells can enter mitosis despite the presence of unrepaired DNA breaks, indicating that cohesin is required for the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint.

Figure 1.

Cohesin prevents the entry of cells into mitosis in the presence of unrepaired DNA DSBs. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental protocol. HeLa cells were synchronized by double-thymidine arrest and were transfected with siRNAs during the first arrest. Six hours after release from the second arrest, cells were irradiated (8 Gy) or treated 15 min with 5 μM of etoposide. One hour after recovery, cells were treated with 2 mM caffeine and arrested in mitosis by nocodazole treatment (0.1 ng/ml). Ten hours later, mitotic chromosomes were spread and stained with Giemsa. (B) Western blot analysis of control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted HeLa cells. (C) Representative picture of mitotic chromosome spreads obtained in (A). Scale bar 10 μm. Note that in many cases, sister chromatids containing few DNA breaks were still connected by cohesion. It is possible that these chromosomes were derived from cells in which Scc1 had been depleted incompletely. In chromosomes with many breaks, it was difficult to assess the cohesion status because of the fragmentation of the chromosomes. (D) Quantification of double-strand break phenotypes shown in (C) (n⩾120).

Earlier work in yeast and human cells has shown that cohesin's role in DNA damage repair depends on the ability of this complex to mediate sister chromatid cohesion (Sjogren and Nasmyth, 2001; Schmitz et al, 2007). To address whether cohesin's function in the G2/M checkpoint is likewise to mediate cohesion, we performed the same experiments as above with sororin-depleted cells. In these cells, cohesin can associate with chromatin, but cannot establish or maintain sister chromatid cohesion (Schmitz et al, 2007). Therefore, if cohesion was required for the G2/M checkpoint, sororin-depleted cells would be predicted to behave as Scc1-depleted cells. However, after DNA damage, sororin-depleted cells behaved similarly to control cells. Only few cells entered mitosis with broken chromosomes, indicating that the G2/M checkpoint had been activated (Figure 1D, upper panels). This observation suggests that sister chromatid cohesion is dispensable for the G2/M checkpoint and that cohesin has a role in the DNA damage checkpoint pathway other than mediating cohesion.

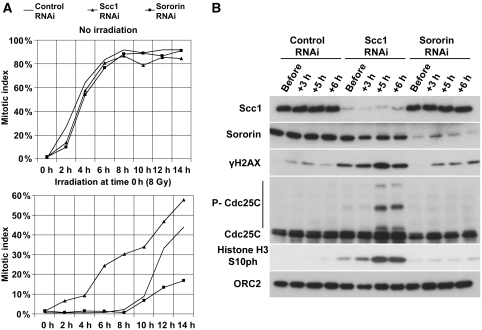

To test more directly the importance of cohesin for the G2/M checkpoint, we measured the mitotic entry kinetics of synchronized control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted cells that had either been irradiated in G2 phase or not. For this purpose, cells were fixed at different time points after release from a double-thymidine arrest and mitotic indices were determined based on chromosome morphology after staining DNA with DAPI. In unirradiated cells, Scc1 and sororin depletion had no effect on cell cycle progression, and all cells entered mitosis with similar kinetics (Figure 2A, upper panel). After irradiation, control cells began to enter mitosis only after a delay of 8 h, indicating that the G2/M checkpoint had been activated (Figure 2A, lower panel). After sororin depletion, only few cells entered mitosis in the course of the experiment, consistent with the notion that sororin-depleted cells were unable to efficiently repair their damaged DNA and remained arrested in G2 phase because of activation of the DNA damage checkpoint. In contrast, Scc1-depleted cells began to enter mitosis as early as unirradiated cells, although at a reduced rate. Scc1 depletion thus impairs the function of the DNA-induced G2/M checkpoint.

Figure 2.

The G2/M DNA damage checkpoint depends on cohesin. Control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted cells were irradiated (8 Gy) in G2 phase. (A) At the indicated times after irradiation, cells were fixed with formaldehyde, stained with DAPI and mitotic indices were determined and plotted as percentages (n>180). (B) Total cell extracts were prepared at the indicated times after irradiation and analysed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies.

We further confirmed this result by immunoblot analyses of cell extracts that were prepared at different times before and after irradiation. In these experiments, mitotic entry was monitored by mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 (H3S10ph) and by a reduced electrophoretic mobility caused by mitotic phosphorylation of the protein Cdc25C. Both mitotic markers appeared after irradiation in Scc1-depleted cells, but not in control- or sororin-depleted cells (Figure 2B). Together, these results show that cohesin, but not sororin, is required for proper functioning of the DNA damage checkpoint in G2 phase.

Cohesin is required for the intra-S phase checkpoint

Earlier work has shown that DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of Smc1 and Smc3 is required for full activation of the intra-S phase checkpoint (Kim et al, 2002; Yazdi et al, 2002; Kitagawa et al, 2004; Luo et al, 2008). These findings, together with our observation that Scc1 and Smc3 are needed for the G2/M checkpoint, raised the possibility that cohesin has a general role in DNA damage checkpoint mechanisms. However, it was also possible that Smc1 and Smc3 have a distinct role in the intra-S checkpoint because these proteins are also subunits of the RC-1 complex, which has also been implicated in DNA repair (Jessberger et al, 1996; Stursberg et al, 1999). To distinguish between these possibilities, we tested whether Smc1 and Smc3 are phosphorylated as part of cohesin and whether cohesin subunits are required for the intra-S phase checkpoint.

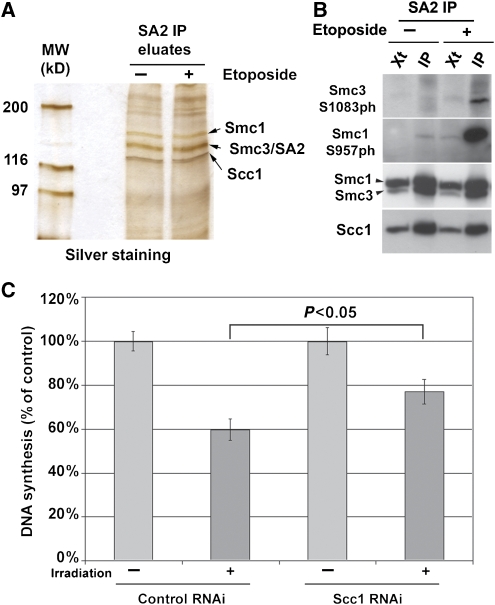

To analyse cohesin phosphorylation, cells were released from a double-thymidine arrest into S phase and DNA damage was induced or not. Subsequently, cohesin subunits were isolated from cell lysates by immunoprecipitation with SA2 antibodies, separated by SDS–PAGE and analysed by silver staining (Figure 3A) or immunoblotting with antibodies specific for phospho-serine 957 on Smc1 (Smc1-S957ph) and phospho-serine 1083 on Smc3 (Smc3-S1083ph; Figure 3B). After irradiation, Smc1-S957ph and Smc3-S1083ph could both be detected in the SA2 immunoprecipitate, but not in control IgG immunoprecipitates (Supplementary Figure 3), indicating that these proteins can be modified as part of cohesin. Furthermore, we observed that DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of Smc1 and Smc3 was almost completely abolished in cells depleted of Scc1 (see Figure 4A below; Supplementary Figure 4). As Scc1 is a subunit of cohesin, and has not been reported to be a subunit of RC-1, this observation implies that Smc1 and Smc3 are phosphorylated predominantly, if not exclusively, as part of cohesin. Further supporting this conclusion, mass spectrometric analysis of proteins recovered from HeLa extracts by immunoprecipitation with Smc3 antibodies identified all known subunits of cohesin, but not DNA polymerase ɛ and DNA ligase III (data not shown). It is possible that RC-1 is only expressed in cells with high recombinational activity, such as thymocytes, from which it was originally purified (Jessberger et al, 1993).

Figure 3.

Cohesin is essential for the intra-S phase checkpoint. (A, B) Cohesin complexes were immunoprecipitated from HeLa protein extracts prepared before (−) or after (+) etoposide-induced DNA damage using SA2 antibodies. (A) Eluates (SA2 IP eluates) were separated by SDS–PAGE and analysed by silver staining. (B) Protein extracts (Xt) and eluates (IP) were processed for western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (C) Radio-resistant DNA synthesis assay was performed for control- and Scc1-depleted cells. Incorporation of 3H-thymidine was determined after irradiation (8 Gy) and expressed relative to that of untreated cells. Two independent experiments were performed, with each condition in triplicates. Data shown represent averages and standard deviations of all six measurements per condition.

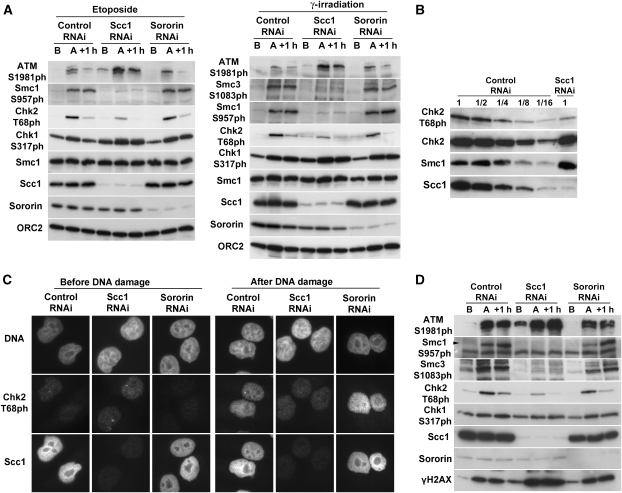

Figure 4.

Full activation of Chk2 by DNA damage depends on cohesin. (A) Control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted cells were synchronized in G2 phase and were either treated with etoposide (5 μM for 15 min, left panel) or irradiated (8 Gy, right panel). Total cell extracts were prepared before (B), immediately after (A) and 1 h after (+1 h) DNA damage induction and analysed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (B) Dilution series of irradiated control and Scc1-depleted cells were analysed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (C) Control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted cells were fixed before or after irradiation in G2 and processed for IFM experiments using anti-Chk2-T68Ph and anti-Scc1 antibodies. DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar 10 μm. (D) Control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted cells were synchronized in S phase and irradiated (8 Gy). Total cell extracts were prepared before (B), immediately after (A) and 1 h after (+1 h) DNA damage induction and analysed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies.

A corollary of these findings is that Scc1, like phosphorylation of Smc1 and Smc3, should be required for the intra-S phase checkpoint. To test this prediction, we irradiated control- and Scc1-depleted cells in S phase and measured the subsequent incorporation of 3H-thymidine into DNA. In cells that are proficient for the intra-S checkpoint, irradiation suppresses 3H-thymidine incorporation partially because firing of ‘late' replication origins is inhibited, whereas DNA synthesis continues from origins that have already been fired (Painter, 1981; Lavin and Schroeder, 1988). Consistent with this notion, 3H-thymidine incorporation was reduced by 40% when control cells were exposed to irradiation, indicating that the intra-S phase checkpoint had been activated (Figure 3C). In contrast, 3H-thymidine incorporation was only reduced by 20% in Scc1-depleted cells. This result differs significantly from the result obtained for control cells (P<0.05, unpaired t-test) and is similar to the reduction in DNA synthesis that has been observed in cells expressing non-phosphorylatable Smc1 or Smc3 (Kim et al, 2002; Yazdi et al, 2002; Luo et al, 2008). These observations indicate that cohesin is required for the intra-S phase checkpoint, and suggest that the earlier described requirement of Smc1 and Smc3 phosphorylation for this checkpoint reflects a role of the cohesin complex in this pathway.

Cohesin is required for complete activation of the checkpoint kinase Chk2

To understand why cohesin-depleted cells fail to properly activate the intra-S and G2/M checkpoint pathways, we tested whether cohesin is needed for activation of checkpoint kinases. We induced DNA damage in control-, Scc1- or sororin-depleted cells by irradiation or etoposide treatment during G2 phase and prepared cell extracts before and after induction of DNA damage. First, we analysed proteins in these extracts by immunoblotting with antibodies that are specific for the activated phosphorylated forms of Chk1 (Chk1-S317ph) and Chk2 (Chk2-T68ph). Compared with control- and sororin-depleted cells, the levels of Chk1-S317 were slightly increased in Scc1-depleted cells. In contrast, the levels of Chk2-T68ph were clearly and reproducibly reduced after Scc1 depletion (Figure 4A; Supplementary Figures 4 and 5). These effects were not because of changes in Chk1 and Chk2 levels, and the effects on Chk2 phosphorylation were specific for T68 because other phospho-sites (Chk2-S19ph, Chk2-S33/35ph) were not reduced (Supplementary Figure 4). Semi-quantitative immunoblot experiments indicated that Chk2 phosphorylation on T68 was reduced to <25% of the levels that were seen in control cells (Figure 4B). Similarly, Chk2 phosphorylation at T68 was reduced by at least 50% in cells depleted of Smc3 (Supplementary Figure 5). The difference in the reduction of Chk2-T68 phosphorylation could be due to the different depletion efficiencies for Scc1 (>90%, Figure 4B) and Smc3 (around 75%, Supplementary Figure 5B). To confirm our immunoblot results, we also analysed Chk2 phosphorylation in IFM experiments. In irradiated Scc1-depleted cells, Chk2-T68ph signals were clearly reduced compared with control- or sororin-depleted cells (Figure 4C). Our data, therefore, indicate that cohesin is required for phosphorylation of Chk2 on T68, which is required for Chk2 activation (Ahn et al, 2000; Matsuoka et al, 2000; Melchionna et al, 2000).

As phosphorylation of Chk2 on T68 depends on ATM (Ahn et al, 2000; Matsuoka et al, 2000; Melchionna et al, 2000), we analysed whether ATM activation is reduced in Scc1-depleted cells. However, the activated form of ATM (ATM-S1981ph) was not reduced, but increased, indicating that reduced Chk2 phosphorylation on T68 is not an indirect consequence of defects in ATM activation (Figure 4A).

We also observed that phosphorylated forms of ATM, Chk1 and the histone H2AX (γH2AX) were more abundant in Scc1- and Smc3-depleted cells even before induction of DNA damage (Figures 2B, 4A and 5B; Supplementary Figures 4 and 5A). This observation suggests that cohesin-depleted cells accumulate spontaneously occurring DSBs because of defects in DNA damage repair.

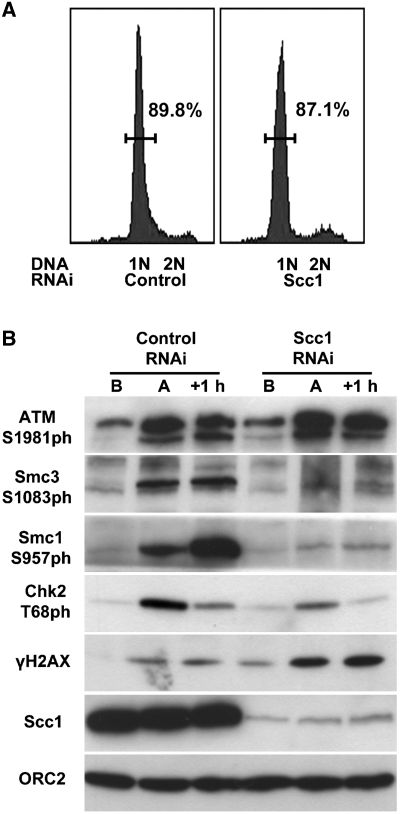

Figure 5.

Cohesin is required for Chk2 activation before chromosome duplication. (A) FACS analysis profiles of control- and Scc1-depleted cells enriched in G1 phase populations by a 14-h release after a double-thymidine arrest. (B) Control- and Scc1-depleted cells were irradiated (8 Gy) in G1 phase. Total cell extracts were prepared before (B), immediately after (A) and 1 h after (+1 h) irradiation and analysed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies.

To address whether cohesin also mediates Chk2 activation in the intra-S phase checkpoint, we synchronized control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted cells in S phase, induced DNA damage by irradiation and analysed phosphorylation of Chk2 and ATM by immunoblotting. Also in this case, a reduction in Chk2-T68ph signal was observed in Scc1-depleted cells, although ATM-S1981ph signals were elevated (Figure 4D). Cohesin is, therefore, also required during S phase for proper activation of Chk2.

The role of cohesin in Chk2 activation is independent of cohesin's function in sister chromatid cohesion

Our finding that cohesin, but not sororin, is required for full phosphorylation of Chk2 on T68 suggested that the role of cohesin in this process is independent of its ability to mediate cohesion. To test this possibility directly, we analysed whether cohesin is also required for Chk2 phosphorylation in G1 phase, that is when cohesion does not exist. Control- and Scc1-depleted cells were released for 14 h from a double-thymidine arrest and DNA damage was induced by irradiation. As estimated by FACS analysis, 85–90% of control cells and Scc1-depleted cells were in G1 phase under these conditions (Figure 5A). Cell lysates were prepared before and at different time points after irradiation, and proteins were analysed by immunoblotting (Figure 5B). As in cells synchronized in G2 and S phases, Chk2-T68ph levels were reduced in Scc1-depleted cells, indicating that cohesin is also required for full Chk2 phosphorylation and activation in G1 phase. The role of cohesin in this process is, therefore, presumably independent of its function in sister chromatid cohesion.

Cohesin is required for efficient recruitment of 53BP1 to DNA break sites

After irradiation, several proteins that are required for the DNA damage response accumulate on chromatin in discrete foci, which are believed to contain DNA break sites (Bekker-Jensen et al, 2006). These IRIFs contain the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 (MRN) complex, the mediator proteins Mdc1 and 53BP1 and phosphorylated forms of H2AX (γH2AX), ATM and Smc1. Recruitment of these proteins into IRIFs has been implicated in activation of the checkpoint effector kinases Chk1 and Chk2 (for review, see Sancar et al, 2004). We, therefore, tested whether cohesin participates in Chk2 activation by mediating the recruitment of DNA damage response proteins to IRIFs. We synchronized control, Scc1- or sororin-depleted cells in G2 phase, induced DNA damage by irradiation and analysed the formation of IRIFs in IFM experiments. The MRN complex subunits Mre11 and Nbs1 and the mediator Mdc1, γH2AX and ATM-S1981ph were enriched in IRIFs similarly in control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted cells (Supplementary Figure 6). Normal amounts of cohesin are, therefore, dispensable for the enrichment of these proteins at DNA break sites. However, we noticed that IRIFs, revealed by Mdc1 and γH2AX staining, seemed larger and more diffuse in Scc1-depleted cells when compared with typical small, well-defined IRIFs in control- or sororin-depleted cells. The presence of cohesin may, therefore, confine IRIFs to discrete regions, or Scc1-depleted cells might contain more IRIFs, which overlap and thus ‘fuse' into larger foci.

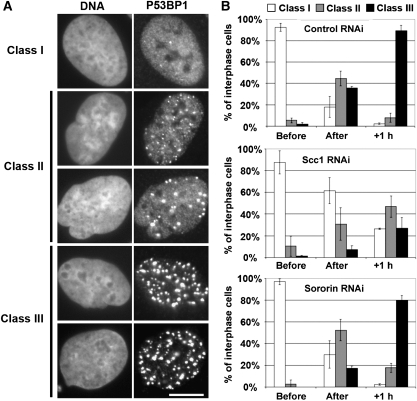

In contrast, the behaviour of the mediator protein 53BP1 differed significantly between control- and Scc1-depleted cells. One hour after irradiation, 90% of control cells and 75% of sororin-depleted cells showed 53BP1 staining almost exclusively in IRIFs and little, if any homogeneous staining throughout the nucleoplasm (Figure 6A and B, Supplementary Figure 7A, ‘Class III' phenotype). In contrast, only 33% of Scc1-depleted cells showed a similar distribution of 53BP1, and the other cells showed either partial recruitment of 53BP1 to IRIFs (40%, ‘Class II') or little or no 53BP1 staining in IRIFs (26%, ‘Class I'). This effect of Scc1 depletion was not simply because of a delay in 53BP1 recruitment as its recruitment was also impaired 3 h after irradiation (Supplementary Figure 7B and C). Cells treated with Smc3 siRNAs also displayed defective recruitment of 53BP1 to damage sites (Supplementary Figure 7C), although to a lesser extent, possibly because Smc3 was depleted less efficiently in our experiments than Scc1. A similar impairment of 53BP1 recruitment was observed when DNA damage was induced in Scc1-depleted cells during S phase (data not shown). It was shown earlier that 53BP1 is required for the DNA damage checkpoints in G2 and S phase and for activating phosphorylation of Chk2 at T68 (DiTullio et al, 2002; Fernandez-Capetillo et al, 2002; Wang et al, 2002; Peng and Chen, 2003), although challenging results were reported (Mochan et al, 2003; Ward et al, 2003). The defective activation of Chk2 in Scc1- and Smc3-depleted cells could, therefore, be due to the impaired recruitment of 53BP1 to DNA break sites.

Figure 6.

53BP1 enrichment at DNA break sites requires cohesin. (A) Representative fluorescence microscopy pictures of control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted HeLa cells irradiated (8 Gy) in G2 phase, processed for immunofluorescence using 53BP1 antibody and counterstained with DAPI. Cells were classified according to 53BP1 pattern in three different classes: homogenous nuclear staining (class I), few foci with diffuse staining (class II) and many strong foci without diffuse staining (class III). Scale bar 10 μm. (B) Quantification of the phenotypes shown in (A) before, immediately after, 1 h (+1 h) after irradiation for control-, Scc1- and sororin-depleted cells. Averages and standard deviations calculated from two independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

The cohesin subunit Rad21/Scc1 and the cohesin-associated protein Rad61/Wapl were first identified in genetic screens in fission and budding yeast for mutants that are hypersensititve to DNA damage (Birkenbihl and Subramani, 1992; Game et al, 2003). Since then it has been well established that cohesin is essential for the repair of damaged DNA and that this function depends on cohesin's ability to mediate sister chromatid cohesion (for review, see Watrin and Peters, 2006; Strom and Sjogren, 2007)). In contrast, it has remained much less clear if cohesin is also required for DNA damage-induced checkpoint mechanisms. In vertebrate cells, phosphorylation of Smc1 and Smc3 is required for the intra-S checkpoint (Kim et al, 2002; Yazdi et al, 2002; Kitagawa et al, 2004; Luo et al, 2008), but in this case, it remained unknown whether these proteins are phosphorylated as part of cohesin or as subunits of the recombinational DNA repair complex RC-1 (Jessberger et al, 1996; Stursberg et al, 1999). Furthermore, it was not known whether Smc1 and Smc3 phosphorylation is specifically required for the intra-S checkpoint, or whether these modifications are also important in other DNA damage-induced checkpoint pathways.

Our work shows that Smc1 and Smc3 are phosphorylated in response to DNA damage as part of cohesin, and that the integrity of the cohesin complex is essential for proper functioning of both the intra-S and the G2/M checkpoints. Our work reveals further that one of cohesin's roles in DNA damage checkpoints is to enable the activating phosphorylation of Chk2 on threonine 68.

Different mechanisms through which cohesin might contribute to checkpoint function can be envisioned. Recently, cohesin has been implicated in gene regulation (reviewed in Dorsett, 2007; Wendt and Peters, 2009). Cohesin could thus affect checkpoint function indirectly by changing the expression of checkpoint genes. However, we have not observed any significant changes in the levels of known checkpoint proteins. We, therefore, favour the idea that cohesin contributes to checkpoint activation directly by interacting with DNA at damage sites. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that cohesin accumulates at DSB sites not only in yeast, but also in mammalian cells (Potts et al, 2006), and that phosphorylated Smc1 accumulates in IRIFs (Kitagawa et al, 2004; Bekker-Jensen et al, 2006). At IRIFs, phosphorylated cohesin might then directly or indirectly mediate the recruitment of other proteins that are required for checkpoint function. Our work revealed that one such protein is 53BP1, whose proper accumulation in IRIFs depends on intact cohesin complexes, whereas cohesin inactivation had no inhibitory effect on Mdc1 and MRN enrichment and on ATM and Chk1 phosphorylation. As 53BP1 has been shown earlier to be required for Chk2 phosphorylation (Wang et al, 2002; Peng and Chen, 2003), it is possible that cohesin participates in Chk2 activation by promoting 53BP1 recruitment at damage sites. However, it is unclear whether Chk2 is essential for cell cycle delay after DNA damage (Matsuoka et al, 1998; Hirao et al, 2000, 2002; Jack et al, 2002; Takai et al, 2002; Rainey et al, 2008; Stracker et al, 2008), and 53BP1 may, therefore, have other, more important roles in checkpoint pathways. Furthermore, no alterations in 53BP1 localization were observed in cells expressing non-phosphorylatable mutants of Smc1, which also show defects in the intra-S checkpoint (Kitagawa et al, 2004). It is, therefore, possible that cohesin is also needed for recruiting other, yet unidentified checkpoint proteins to IRIFs. Understanding how cohesin mediates DNA damage checkpoint function will, therefore, remain an important task for the future.

Although the levels of Chk2T68ph were always reduced after depletion of cohesin, we found that the levels of phosphorylated ATM, H2AX and Chk1 were increased not only after induction of DNA damage, but even in the absence of experimentally induced DNA damage. A similar phenomenon has been observed in Chk1-depleted cells in which DNA damage and phosphorylation of H2AX are also increased (Syljuasen et al, 2005). It is, therefore, possible that cohesin-depleted cells accumulate spontaneously occurring DNA damage. This accumulation might entirely be due to cohesin's role in DNA damage repair, but it is conceivable that DNA lacking cohesin undergoes changes in chromatin structure that in addition make DNA more prone to the occurrence of damage. In either case, an important implication of these findings is that cohesin-depleted cells may be exposed to higher levels of DNA damage checkpoint signalling than control cells. One would, therefore, expect checkpoint-induced cell cycle delays to be stronger in cohesin-depleted cells than in cohesin proficient cells. The fact that the opposite phenomenon is observed suggests that cohesin has a particularly important role in checkpoint signalling ‘downstream' of the activation of checkpoint kinases.

In contrast to cohesin's role in DNA damage repair, several of our observations indicate that the checkpoint function of cohesin is independent of its canonical role in sister chromatid cohesion. In sororin-depleted cells, the G2/M checkpoint functions normally, despite sister chromatid cohesion and DNA DSB repair being as defective in these cells as they are in cells depleted of cohesin (Schmitz et al, 2007). Although normal amounts of cohesin can associate with DNA in sororin-depleted cells, this ‘non-cohesive' binding seems to be sufficient for the checkpoint function of cohesin. Furthermore, we show that cohesin is also required for Chk2 activation during G1 phase in which sister chromatid cohesion does not exist, further supporting that the function of cohesin in DNA damage checkpoint pathways is independent of its role in cohesion.

This aspect of our results may have important medical implications for understanding Cornelia de Lange Syndrome (CdLS), a human disease that can be caused by hypomorphic mutations in cohesin and the cohesin-loading factor NIPBL/Scc2 (Krantz et al, 2004; Tonkin et al, 2004). As sister chromatid cohesion seems to be largely normal in CdLS patients (Tonkin et al, 2004), it is thought that this disease is caused by cohesion-independent functions of cohesin (Dorsett, 2007), in particular in transcriptional regulation (Parelho et al, 2008; Wendt et al, 2008; Liu et al, 2009). Our work raises the possibility that CdLS patients may also suffer from defects in DNA damage checkpoints and thus react atypically to DNA damage. Addressing these questions will be important for understanding the etiology of CdLS and for adjusting DNA damage-based therapies to the specific needs of these patients.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Antibodies to Scc1 (rabbit 575, 623 and mouse), SA2 (447), Smc1, Smc3 (727), sororin, ORC2, Cdc25C, Phospho-Histone H3 (S10), hCAP-D2, Sgo1, Cyclin A and Cyclin B1 have been described (Watrin and Legagneux, 2005; Watrin et al, 2006; Lenart et al, 2007; Schmitz et al, 2007). Mouse monoclonal Phospho-ATM (S1981, #05-740, clone 10H11.E2), Phospho-Smc1 (S957, #05-786, clone 5D11G5) and Chk1 (#05-965, clone 2G11D5) antibodies were from Upstate and RPA antibodies (Ab1, 9H8) from Neomarkers. Rabbit Phospho-Chk1 (S317, #2344), γH2AX (S139, #2577) and Phospho-Chk2 (T68, #2661; S33/35, #2665; S19, #2666) antibodies were from Cell Signalling Technology, 53BP1 (NB100-304) antibodies from Novus Biological, Phospho-Smc3 (S1083, A300-480A) from Bethyl Laboratories and Chk2 antibodies (ab8108) from Abcam.

Cell culture, irradiation and RNAi

HeLa cells were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 0.2 mM L-glutamine and antibiotics (all Invitrogen). U2OS Nbs1-GFP cells and their maintenance were described earlier (Lukas et al, 2004). Cells were synchronized by a double-thymidine arrest protocol as described in Schmitz et al (2007). Etoposide was used at 5 μM and caffeine at 2 mM (all from Sigma). Etoposide was washed out by two 5-min washes at 37°C in pre-warmed PBS. γ-irradiation was performed in a Gammacell 3000 Elan irradiator from MDS Nordion (4 Gy per min.). Synthetic siRNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Ambion. Sequences and transfection of siRNAs have been described (Watrin et al, 2006; Schmitz et al, 2007; Wendt et al, 2008). Cells were used 48 h after transfection.

FACS analysis

FACS analyses were performed as in Schmitz et al (2007).

Radio-resistant DNA synthesis assay

Control cells and Scc1-depleted cells were released for 2 h from a thymidine arrest, and irradiated (8 Gy). After 45 min, 3H-labelled thymidine was added to the cell medium for 15 min, and then washed out. Twenty minutes later, cells were directly resuspended in 0.2 mM NaOH, diluted in scintillation cocktail (UltimaGold, PerkinElmer) according to manufacturer's instructions and incorporated radioactivity was measured by scintillation counting. Two independent experiments were performed, and each sample was made in triplicate; the results of all six measurements were used to calculate averages and standard deviations. Statistical significance of mean difference was assessed by unpaired t-test using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad software).

Immunofluorescence and chromosome spreads

Cell fixation with formaldehyde, immunofluorescence experiments and mitotic chromosome spreads were performed as described earlier (Watrin et al, 2006). For RPA, staining cells were fixed in a 1:1 methanol/acetone mixture for 20 min at −20°C and processed as described (Watrin et al, 2006).

Protein extracts

Sub-confluent HeLa cells were scraped off culture plates and washed thrice with ice-cold PBS. Cell pellet was resuspended in extraction buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM magnesium chloride, 0.2% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol) in the presence of protease-inhibitor mix (leupeptin, chymostatin and pepstatin, 10 μg/ml final each) and phosphatase inhibitors (10 mM sodium fluoride, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM EDTA and 1 μM okadaic acid). Cells were lysed on ice using a dounce homogenizer. After centrifugation (10 000 g for 15 min at 4°C), soluble protein extract was collected and used for further applications. Typically, 2 ml of extraction buffer were used for 10 15-cm Petri dishes, yielding 2 ml of protein extract at 8–12 mg/ml.

Immunoprecipitations and western blot analysis

Purified antibodies were covalently coupled to Affiprep protein A beads (Biorad, 1 μg of antibody per μl of bead) and washed with TBS containing 0.01% Triton-X 100. For immunoprecipitation, 10 μl of beads were incubated with 100 μl of 10 mg/ml protein extract for 1 h at 4°C, washed and eluted twice with 100 mM glycin (pH2) or directly resuspended in SDS–PAGE sample buffer. For western blotting, proteins were separated by 7–13% SDS–PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane and detected by incubation with antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxydase (Jackson Laboratories) and enhanced chemoluminescence.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Review Process File

Acknowledgments

We thank Claudia Lukas and Jiri Lukas for Nbs1-GFP U2OS cells, Yoshinori Watanabe for Sgo1 antibodies and Karl Mechtler for mass spectrometry. We are grateful to Claudia Lukas, Jiri Lukas, Peter Lenart, Mark Petronczki and Michael Yaffe for helpful discussions. Research in the laboratory of J-MP is supported by Boehringer Ingelheim, the Austrian Science Fund through the EuroDYNA Program of the European Science Foundation and the Austrian Research Promotion Agency through the Special Research Program ‘Chromosome Dynamics'.

References

- Ahn JY, Schwarz JK, Piwnica-Worms H, Canman CE (2000) Threonine 68 phosphorylation by ataxia telangiectasia mutated is required for efficient activation of Chk2 in response to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res 60: 5934–5936 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekker-Jensen S, Lukas C, Kitagawa R, Melander F, Kastan MB, Bartek J, Lukas J (2006) Spatial organization of the mammalian genome surveillance machinery in response to DNA strand breaks. J Cell Biol 173: 195–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkenbihl RP, Subramani S (1992) Cloning and characterization of rad21 an essential gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe involved in DNA double-strand-break repair. Nucleic Acids Res 20: 6605–6611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiTullio RA Jr, Mochan TA, Venere M, Bartkova J, Sehested M, Bartek J, Halazonetis TD (2002) 53BP1 functions in an ATM-dependent checkpoint pathway that is constitutively activated in human cancer. Nat Cell Biol 4: 998–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsett D (2007) Roles of the sister chromatid cohesion apparatus in gene expression, development, and human syndromes. Chromosoma 116: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Capetillo O, Chen HT, Celeste A, Ward I, Romanienko PJ, Morales JC, Naka K, Xia Z, Camerini-Otero RD, Motoyama N, Carpenter PB, Bonner WM, Chen J, Nussenzweig A (2002) DNA damage-induced G2-M checkpoint activation by histone H2AX and 53BP1. Nat Cell Biol 4: 993–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Game JC, Birrell GW, Brown JA, Shibata T, Baccari C, Chu AM, Williamson MS, Brown JM (2003) Use of a genome-wide approach to identify new genes that control resistance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to ionizing radiation. Radiat Res 160: 14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V, Koshland D, Strunnikov A (1997) A direct link between sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome condensation revealed through the analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae. Cell 91: 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauf S, Roitinger E, Koch B, Dittrich CM, Mechtler K, Peters JM (2005) Dissociation of cohesin from chromosome arms and loss of arm cohesion during early mitosis depends on phosphorylation of SA2. PLoS Biol 3: e69. (e-pub 2005 Mar 2001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao A, Cheung A, Duncan G, Girard PM, Elia AJ, Wakeham A, Okada H, Sarkissian T, Wong JA, Sakai T, De Stanchina E, Bristow RG, Suda T, Lowe SW, Jeggo PA, Elledge SJ, Mak TW (2002) Chk2 is a tumor suppressor that regulates apoptosis in both an ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-dependent and an ATM-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol 22: 6521–6532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao A, Kong YY, Matsuoka S, Wakeham A, Ruland J, Yoshida H, Liu D, Elledge SJ, Mak TW (2000) DNA damage-induced activation of p53 by the checkpoint kinase Chk2. Science 287: 1824–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack MT, Woo RA, Hirao A, Cheung A, Mak TW, Lee PW (2002) Chk2 is dispensable for p53-mediated G1 arrest but is required for a latent p53-mediated apoptotic response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 9825–9829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessberger R, Podust V, Hubscher U, Berg P (1993) A mammalian protein complex that repairs double-strand breaks and deletions by recombination. J Biol Chem 268: 15070–15079 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessberger R, Riwar B, Baechtold H, Akhmedov AT (1996) SMC proteins constitute two subunits of the mammalian recombination complex RC-1. EMBO J 15: 4061–4068 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ST, Xu B, Kastan MB (2002) Involvement of the cohesin protein, Smc1, in Atm-dependent and independent responses to DNA damage. Genes Dev 16: 560–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa R, Bakkenist CJ, McKinnon PJ, Kastan MB (2004) Phosphorylation of SMC1 is a critical downstream event in the ATM-NBS1-BRCA1 pathway. Genes Dev 18: 1423–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz ID, McCallum J, DeScipio C, Kaur M, Gillis LA, Yaeger D, Jukofsky L, Wasserman N, Bottani A, Morris CA, Nowaczyk MJ, Toriello H, Bamshad MJ, Carey JC, Rappaport E, Kawauchi S, Lander AD, Calof AL, Li HH, Devoto M et al. (2004) Cornelia de Lange syndrome is caused by mutations in NIPBL, the human homolog of Drosophila melanogaster Nipped-B. Nat Genet 36: 631–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin MF, Schroeder AL (1988) Damage-resistant DNA synthesis in eukaryotes. Mutat Res 193: 193–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenart P, Petronczki M, Steegmaier M, Di Fiore B, Lipp JJ, Hoffmann M, Rettig WJ, Kraut N, Peters JM (2007) The small-molecule inhibitor BI 2536 reveals novel insights into mitotic roles of polo-like kinase 1. Curr Biol 17: 304–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhang Z, Bando M, Itoh T, Deardorff MA, Clark D, Kaur M, Tandy S, Kondoh T, Rappaport E, Spinner NB, Vega H, Jackson LG, Shirahige K, Krantz ID (2009) Transcriptional dysregulation in NIPBL and cohesin mutant human cells. PLoS Biol 7: e1000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada A, Hirano M, Hirano T (1998) Identification of Xenopus SMC protein complexes required for sister chromatid cohesion. Genes Dev 12: 1986–1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas C, Melander F, Stucki M, Falck J, Bekker-Jensen S, Goldberg M, Lerenthal Y, Jackson SP, Bartek J, Lukas J (2004) Mdc1 couples DNA double-strand break recognition by Nbs1 with its H2AX-dependent chromatin retention. EMBO J 23: 2674–2683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Li Y, Mu JJ, Zhang J, Tonaka T, Hamamori Y, Jung SY, Wang Y, Qin J (2008) Regulation of intra-S phase checkpoint by ionizing radiation (IR)-dependent and IR-independent phosphorylation of SMC3. J Biol Chem 283: 19176–19183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge SJ (1998) Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science 282: 1893–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka S, Rotman G, Ogawa A, Shiloh Y, Tamai K, Elledge SJ (2000) Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated phosphorylates Chk2 in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 10389–10394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchionna R, Chen XB, Blasina A, McGowan CH (2000) Threonine 68 is required for radiation-induced phosphorylation and activation of Cds1. Nat Cell Biol 2: 762–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K (1997) Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell 91: 35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochan TA, Venere M, DiTullio RA Jr, Halazonetis TD (2003) 53BP1 and NFBD1/MDC1-Nbs1 function in parallel interacting pathways activating ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) in response to DNA damage. Cancer Res 63: 8586–8591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter RB (1981) Radioresistant DNA synthesis: an intrinsic feature of ataxia telangiectasia. Mutat Res 84: 183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parelho V, Hadjur S, Spivakov M, Leleu M, Sauer S, Gregson HC, Jarmuz A, Canzonetta C, Webster Z, Nesterova T, Cobb BS, Yokomori K, Dillon N, Aragon L, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M (2008) Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell 132: 422–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng A, Chen PL (2003) NFBD1, like 53BP1, is an early and redundant transducer mediating Chk2 phosphorylation in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem 278: 8873–8876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts PR, Porteus MH, Yu H (2006) Human SMC5/6 complex promotes sister chromatid homologous recombination by recruiting the SMC1/3 cohesin complex to double-strand breaks. EMBO J 25: 3377–3388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey MD, Black EJ, Zachos G, Gillespie DA (2008) Chk2 is required for optimal mitotic delay in response to irradiation-induced DNA damage incurred in G2 phase. Oncogene 27: 896–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin S, Ayad NG, Kirschner MW (2005) Sororin, a substrate of the anaphase-promoting complex, is required for sister chromatid cohesion in vertebrates. Mol Cell 18: 185–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S (2004) Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem 73: 39–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schar P, Fasi M, Jessberger R (2004) SMC1 coordinates DNA double-strand break repair pathways. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 3921–3929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J, Watrin E, Lenart P, Mechtler K, Peters JM (2007) Sororin is required for stable binding of cohesin to chromatin and for sister chromatid cohesion in interphase. Curr Biol 17: 630–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh Y (2001) ATM and ATR: networking cellular responses to DNA damage. Curr Opin Genet Dev 11: 71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjogren C, Nasmyth K (2001) Sister chromatid cohesion is required for postreplicative double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Biol 11: 991–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda E, Matsusaka T, Morrison C, Vagnarelli P, Hoshi O, Ushiki T, Nojima K, Fukagawa T, Waizenegger IC, Peters JM, Earnshaw WC, Takeda S (2001) Scc1/Rad21/Mcd1 is required for sister chromatid cohesion and kinetochore function in vertebrate cells. Dev Cell 1: 759–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker TH, Couto SS, Cordon-Cardo C, Matos T, Petrini JH (2008) Chk2 suppresses the oncogenic potential of DNA replication-associated DNA damage. Mol Cell 31: 21–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom L, Karlsson C, Lindroos HB, Wedahl S, Katou Y, Shirahige K, Sjogren C (2007) Postreplicative formation of cohesion is required for repair and induced by a single DNA break. Science 317: 242–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom L, Sjogren C (2005) DNA damage-induced cohesion. Cell Cycle 4: 536–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom L, Sjogren C (2007) Chromosome segregation and double-strand break repair—a complex connection. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stursberg S, Riwar B, Jessberger R (1999) Cloning and characterization of mammalian SMC1 and SMC3 genes and proteins, components of the DNA recombination complexes RC-1. Gene 228: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumara I, Vorlaufer E, Gieffers C, Peters BH, Peters JM (2000) Characterization of vertebrate cohesin complexes and their regulation in prophase. J Cell Biol 151: 749–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syljuasen RG, Sorensen CS, Hansen LT, Fugger K, Lundin C, Johansson F, Helleday T, Sehested M, Lukas J, Bartek J (2005) Inhibition of human Chk1 causes increased initiation of DNA replication, phosphorylation of ATR targets, and DNA breakage. Mol Cell Biol 25: 3553–3562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai H, Naka K, Okada Y, Watanabe M, Harada N, Saito S, Anderson CW, Appella E, Nakanishi M, Suzuki H, Nagashima K, Sawa H, Ikeda K, Motoyama N (2002) Chk2-deficient mice exhibit radioresistance and defective p53-mediated transcription. EMBO J 21: 5195–5205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin ET, Wang TJ, Lisgo S, Bamshad MJ, Strachan T (2004) NIPBL, encoding a homolog of fungal Scc2-type sister chromatid cohesion proteins and fly Nipped-B, is mutated in Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Nat Genet 36: 636–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unal E, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Koshland D (2007) DNA double-strand breaks trigger genome-wide sister-chromatid cohesion through Eco1 (Ctf7). Science 317: 245–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Matsuoka S, Carpenter PB, Elledge SJ (2002) 53BP1, a mediator of the DNA damage checkpoint. Science 298: 1435–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward IM, Minn K, van Deursen J, Chen J (2003) p53 binding protein 53BP1 is required for DNA damage responses and tumor suppression in mice. Mol Cell Biol 23: 2556–2563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watrin E, Legagneux V (2005) Contribution of hCAP-D2, a non-SMC subunit of condensin I, to chromosome and chromosomal protein dynamics during mitosis. Mol Cell Biol 25: 740–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watrin E, Peters JM (2006) Cohesin and DNA damage repair. Exp Cell Res 312: 2687–2693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watrin E, Schleiffer A, Tanaka K, Eisenhaber F, Nasmyth K, Peters JM (2006) Human scc4 is required for cohesin binding to chromatin, sister-chromatid cohesion, and mitotic progression. Curr Biol 16: 863–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt KS, Peters JM (2009) How cohesin and CTCF cooperate in regulating gene expression. Chromosome Res 17: 201–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt KS, Yoshida K, Itoh T, Bando M, Koch B, Schirghuber E, Tsutsumi S, Nagae G, Ishihara K, Mishiro T, Yahata K, Imamoto F, Aburatani H, Nakao M, Imamoto N, Maeshima K, Shirahige K, Peters JM (2008) Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature 451: 796–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi PT, Wang Y, Zhao S, Patel N, Lee EY, Qin J (2002) SMC1 is a downstream effector in the ATM/NBS1 branch of the human S-phase checkpoint. Genes Dev 16: 571–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Review Process File