Abstract

There is a great need for biodegradable polymer scaffolds that can regulate the delivery of bioactive factors such as drugs, plasmids, and proteins. Coaxial electrospinning is a novel technique that is currently being explored to create such polymer scaffolds by embedding within them aqueous-based biological molecules. In this study, we evaluated the influence of various processing parameters such as sheath polymer concentration, core polymer concentration and molecular weight, and salt ions within the core polymer on coaxial fiber morphology. The sheath polymer used in this study was poly(ɛ-caprolactone) (PCL), and the core polymer was poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). We examined the effects of the various processing parameters on core diameters, total fiber diameters, and sheath thicknesses of coaxial microfibers using a 24 full factorial statistical model. The maximum increase in total fiber diameter was observed with increase in sheath polymer (PCL) concentration from 9 to 11 wt% (0.49 ± 0.03 μm) and salt concentration within the core from 0 to 500 mM (0.38 ± 0.03 μm). The core fiber diameter was most influenced by the sheath and core polymer (PCL and PEG, respectively) concentrations, the latter of which increased from 200 to 400 mg/mL (0.40 ± 0.01 μm and 0.36 ± 0.01 μm, respectively). The core polymer (PEG) concentration had a maximal negative effect on sheath thickness (0.40 ± 0.03 μm), while salt concentration had the maximal positive effect (0.28 ± 0.03 μm). Molecular weight increases in core polymer (PEG) from 1.0 to 4.6 kDa caused moderate increases in total and sheath fiber diameters and sheath thicknesses. These experiments provide important information that lays the foundation required for the synthesis of coaxial fibers with tunable dimensions.

Introduction

The fabrication of nonwoven fiber meshes with electrospinning is becoming increasingly popular in numerous fields. This technology is now being adapted in textiles,1–4 drug delivery,5–10 surgical and wound dressings,11–16 tissue engineering,17–21 as well as in the field of electronics.22,23 A modification of the well-known single polymer-solvent electrospinning technique (hereafter referred to as conventional electrospinning) is coaxial electrospinning, a fabrication method that produces fibers with a coaxial core and sheath component, where each component can have different solubilities in organic and aqueous solvents. In this case the core is hydrophilic to facilitate the loading and preservation of bioactivity of biological molecules, whereas the sheath is hydrophobic to allow fiber formation after evaporation of the volatile organic solvent. The advantages of such a technique to the tissue engineering community are significant; it allows for the creation of scaffolds that act as reservoirs, and fibers that allow for controlled release of aqueous-based biological molecules. Although biological molecules such as plasmids,24 growth factors,16,25,26 and drugs10,27,28 have been incorporated into conventional electrospun fibers, coaxial fibers have shown greater potential in maintaining bioactivity and extended release. For example, Zhang et al.29 and Jiang et al.,30 among others, have demonstrated that when proteins such as bovine serum albumin (BSA) and lysozyme were incorporated into the cores of coaxial fibers, they exhibited minimal burst release, an extended duration of sustained release, and significantly less aggregation of the bioactive compound than their incorporation by conventional blend and emulsion electrospinning techniques. Additionally, experiments by Liao et al.31 have demonstrated that platelet-derived growth factor, when released from coaxial fiber meshes over a period of 20 days, is as potent as fresh platelet-derived growth factor in promoting proliferation of NIH 3T3 fibroblasts.

An increasing number of attempts are being made to determine the parameters that control the morphology and dimensions of the coaxial fibers. These parameters can play an integral role in the rate of degradation of coaxial fiber mesh scaffolds as well as diffusion and release of the compounds embedded within them. Thus far, there has been a reasonable understanding of the mechanism behind conventional electrospinning and the factors that control the fiber morphology. For example, numerous studies have shown that an increase in polymer viscosity by increasing either the molecular weight or concentration increases the average fiber diameter and decreases bead formation within fibers.32–34 Further, increasing the dielectric constant of the electrospun solvents causes the fiber diameter to decrease.35–37 Other factors such as humidity,38 flow rates,39 voltage,32 distance between the polymer outlet and collecting plate,40 and diameter of the polymer ejecting orifice39 also play significant roles in determining fiber morphology. However, similar data on coaxial fiber morphology is more limited. Initial studies by Zhang et al. have shown a positive correlation between the core polymer (gelatin) concentration41 as well as core flow rates30 on overall fiber diameters. In other studies, Wang et al.42 reported that increases in core and sheath polymer flow rates increase the inner and outer diameters of the fibers. Some of the limitations in identifying these relationships come with a limited understanding of the complex electro-hydrodynamic interactions between the core and sheath solutions during the electrospinning process, which in turn contributes to limitations in designing coaxial fibers with specific dimensions.

In this study, the following four factors and their role in coaxial fiber morphology were evaluated: (i) sheath polymer concentration, (ii) core polymer concentration (iii) core polymer molecular weight, and (iv) sodium chloride (NaCl) ionic concentration in the aqueous core polymer solution. This study describes the variability in fiber morphology within a scaffold based on the factors mentioned above. Further, this study also describes the influence of the factors mentioned above upon core, sheath, and total fiber diameters using a full factorial statistical model. This model is a powerful method for determining the influence of each of the processing parameters upon fiber dimensions. Although other biodegradable polymers can be used to manufacture similar coaxial fiber scaffolds, we have used poly(ɛ-caprolactone) (PCL) in an organic (hydrophobic) solvent as the sheath polymer and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) in an aqueous solvent as the core polymer. These polymers were selected as model polymers because they have been used and characterized extensively for various applications, both in our laboratory as well as by the research community in general. To differentiate the location of the PCL sheath and the PEG core fibers, fluorescent markers were added to each of the polymer solutions, which allowed their visualization with confocal microscopy. The red fluorescence (associated with DiI, mixed with the PCL sheath solution) and green fluorescence (associated with fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] mixed with the aqueous PEG core solution) facilitated distinction of the sheath and core morphology of the fibers. This methodology has elucidated the parameters necessary for the fabrication of coaxial fibers of desired dimensions.

Methods

Solution for fiber sheath

For the fabrication of sheaths for the microfibers, PCL (MW = 80,000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved overnight in 3:1 w/v chloroform (CHCl3):methanol (CH3OH) at 9 or 11 wt%. Immediately before electrospinning, Vibrant® DiI (Cat. # V-22885; Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) was mixed with the PCL solution at 1.33 μL of DiI per 1 mL of PCL solution followed by thorough mixing with the vortexer. Aluminum foil was wrapped around the vials containing the solutions to protect them from light.

Solution for fiber core

For fabricating the cores of the coaxial microfibers, PEG (1.0 or 4.6 kDa) (Sigma) was mixed with water or 500 mM NaCl solution at 200 or 400 mg/mL concentration. The solutions were vortexed and placed on a shaker table until complete dissolution was achieved. About 0.05 wt% FITC (Sigma) was added to the PEG solutions immediately before electrospinning. After addition of FITC, the solutions were mixed with the vortexer for homogeneity. Aluminum foil was wrapped around the vials containing the solutions to protect them from light.

Factorial analysis of variables

A 24 factorial design was formulated followed by analysis of variance to evaluate the influence of PCL concentration, PEG molecular weight, PEG concentration, and NaCl concentration on total fiber diameters and sheath thicknesses as noted in Table 1. High and low concentrations of PCL were synthesized at 11 and 9 wt%, respectively. PEG molecular weights with a high value of 4.6 kDa and a low value of 1.0 kDa were similarly used. PEG solutions from each of the two molecular weights were mixed at a high PEG concentration of 400 mg/mL and a low concentration of 200 mg/mL. The PEG polymers were dissolved either in water (low value for NaCl concentration) or in 500 mM of NaCl solution (high value for NaCl concentration).

Table 1.

24 Factorial Design to Evaluate the Influence of PCL Concentration, PEG Molecular Weight, PEG Concentration, and NaCl Concentration on Coaxial Electrospun Fibers

| Variables | PCL concentration (wt%) | PEG molecular weight (kDa) | PEG concentration (mg/mL) | NaCl concentration (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 11 (P) | 4.6 (W) | 400 (C) | 500 (N) |

| Low | 9 (p) | 1 (w) | 200 (c) | 0 (n) |

Two levels of each of the four factors were used for evaluation; the levels are denoted as high for higher concentrations and low for lower of the two concentrations of each of the factors. The letters next to the values denote the symbol used for representing each of the conditions in subsequent explanation of Results and Discussion.

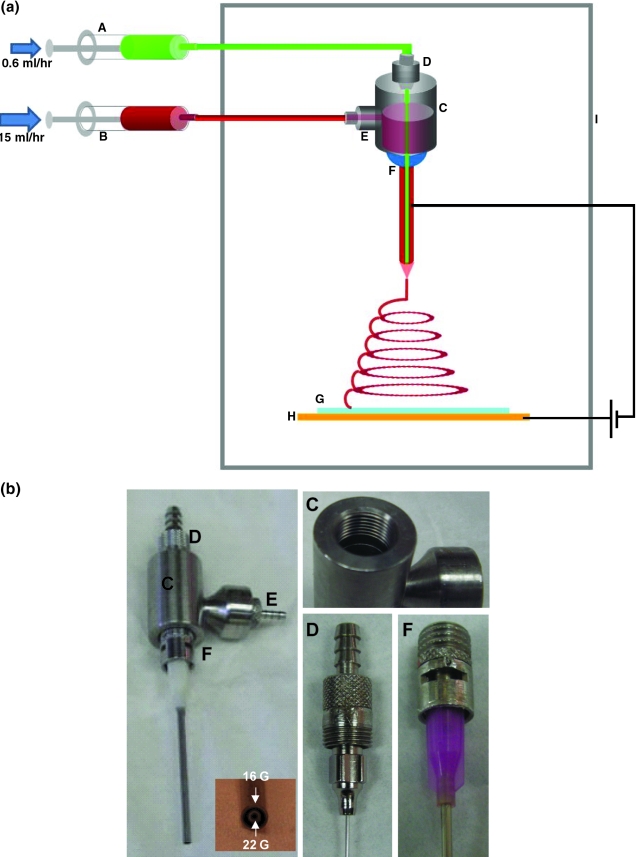

Electrospinning apparatus

The schematic in Figure 1 represents the electrospinning setup for the electrospun nonwoven coaxial fibers. The setup consisted of two syringe pumps (Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) set to different flow rates (15 mL/h for the sheath flow rate and 0.6 mL/h for the core flow rate), a power supply (Gamma High Voltage Research, Ormond Beach, FL), and a square, grounded copper plate (11 × 11 × 0.3 cm). Two 10 mL syringes were filled with the core solution (PEG) and sheath solution (PCL), respectively. The syringes were connected to the reservoir via silicon tubes attached to luers (Small Parts, Miramar, FL) that screwed into a steel reservoir. The reservoir had three luers, two of which were connected to needles: a 22-gauge (ID = 0.0464 mm) inner needle and a 16-gauge (ID = 1.3589 mm) outer needle, respectively (Brico Medical Supplies, Metuchen, NJ), placed concentric to each other (Fig. 1, inset b). The needles were locked into their respective luers, after which the leurs were threaded into the reservoir (C) as shown in Figure 1(b). This fixed the needles in a concentric conformation during the process of electrospinning. The third luer led into the reservoir and provided an inlet for the PCL solutions. The positive lead from the power supply was attached to the needle, whereas the negative lead was connected to the copper plate placed at a distance of 22 cm from the tips of the concentric needles. The reservoir, needles and the copper, and glass plates were set up in a plexi-glass box as shown in Figure 1 with the syringes and power supply directly outside for easy manipulation. The nonwoven coaxial fibers were collected onto a glass plate (0.22 cm thick) placed above the copper plate in a vertical setup. Before use, the glass plates were washed with warm water and soap, and dried with Kimwipes.

FIG. 1.

Coaxial electrospinning setup: (a) The device involves two syringes (A and B) that contain the aqueous and organic phase of the coaxial solutions, respectively. The solutions are independently fed to a reservoir (C). The reservoir contains an opening at the top that allows for attachment of a male luer (D) with a 22-gauge needle. Similarly, another male leur (E) screws into the side of the reservoir that carries the organic solution into the reservoir. The reservoir empties into a 16-gauge needle (F) attached to the bottom of the reservoir. The 22-gauge needle passes coaxially through the reservoir and the 16-gauge needle and its tip is flush with the 16-gauge needle. Potential difference is applied between a copper plate and the 16-gauge needle as indicated. Fibers are collected on a glass plate (G) placed on top of the copper plate (H). This setup is housed in a plexi-glass box (I) as indicated. (b) The actual reservoir used for these experiments is made from stainless steel. The inset shows the concentric needle tips. Outer needle is 16-gauge and inner needle is 22-gauge. The setup can be assembled and disassembled easily due to the screw threads that have been designed into the reservoir and luers as shown. The threads and the luers help lock the needles in a concentric position.

A voltage between 19 and 21 kV was applied between the needle and copper plate to induce electrospinning of the polymer solutions for 3 min. After electrospinning, the electrospun sheets were dried overnight in a chemical fume hood. For confocal analysis, the sheets were cut into sections (3.5 ×1.5 cm, cut from the periphery toward the center of each mat) and placed between two glass cover slips (Fisherbrand, Pittsburgh, PA). For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, the sheets were cut into 1 × 1 cm squares and placed on a stage lined with nonconducting tape. Three nonwoven mats were spun for each of the parameters and used for analysis.

Analysis of fiber morphology

SEM

SEM analysis on the fibers was performed as previously described.43 Briefly, electrospun scaffolds were sputter-coated with gold for 1 min and observed with an FEI-XL 30 environmental scanning electron microscope (Mawah, NJ) at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. For quantification of fiber diameter, measurements were made on the first eight fibers that intersected from left to right, a line drawn horizontally across the middle of an image (at 2500 × magnification). Images from four random locations (selected blindly at 50 × magnification) from each of the three scaffold mats were used for a total of 96 measurements.

Confocal microscopy

Sections of nonwoven electrospun scaffolds were placed between glass cover slips as noted above and were mounted on the stage of a Zeiss LSM 510 (Thornwood, NY) confocal microscope. The scaffolds were excited with argon (488 nm, 6% power) or helium-neon (543 nm, 25% power) lasers configured for multitrack imaging and imaged with a 63 × /1.4NA objective. The emission of FITC was detected using a 510–550 nm bandpass filter, and the emission of DiI was detected using a low-pass 560-nm filter. This configuration was used to prevent overlap between the two emission wavelengths.

The cover slips were scanned along the long axis moving from the right edge to the left. Four independent visual fields were selected randomly on each of the samples at approximately 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80% of the total length from the right most edge of the cover slips. All fibers within a focal plane in that field were scanned and recorded. The focal plane was then reconfigured to record additional fibers in that location. A total of 30 fibers were imaged per mat. The core and total fiber diameters were measured using Zeiss LSM 5 Image Browser (v.3,2,0,115) by two independent observers. Sheath thicknesses were calculated as a difference between the total and inner fiber diameters:

|

(1) |

Readings by both observers were incorporated and evaluated by statistical software (JMP® software; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, v5.1) to determine the influence of the various processing parameters on fiber morphology.

Analysis of fibers after incubation in aqueous medium

To determine if the submicron fibers had a thin PCL sheath that surrounded the fibers, five scaffolds each of 8 mm diameter from two groups of scaffolds made from 9 wt% PCL were incubated in 2 mL phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) for a period of 3 days. The fibers were placed on a shaker table operating at 115 rpm in a warm room (37°C). The polypropylene tubes holding these scaffolds were covered with aluminum foil to prevent photo-bleaching. After 3 days, two scaffolds from each group were analyzed using confocal microscopy as previously described. Three scaffolds were analyzed with SEM for fiber diameter measurements as described above.

Statistical analysis

The resultant data of inner and total fiber diameters and the sheath thickness were analyzed using analysis of variance with the SAS JMP software. The total diameter, inner diameter, and sheath thickness were selected as response variables, whereas PCL concentration, PEG molecular weight, PEG concentration, and NaCl concentration were selected as predictors. The analysis provided least squares mean diameters at each of the high and low levels of the predictors. To estimate the influence of each of the factors at high versus low values, the high least squares mean diameter was subtracted from the low least squares mean diameter value, and the resultant standard errors were calculated using the following formula:

|

(2) |

Results and Discussion

The specific objective of this study was to understand the influence of sheath polymer concentration, core polymer concentration and molecular weight, and NaCl concentration within the core solution on coaxial fiber morphology. The factors used to study the influence of these processing parameters are shown in Table 1. These parameters were selected based on preliminary studies that established concentration and molecular weight ranges that resulted in a stable Taylor cone and produced continuous fibers without apparent defects (such as beading or clumping).

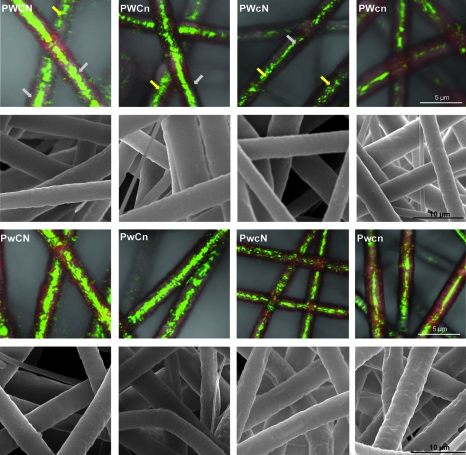

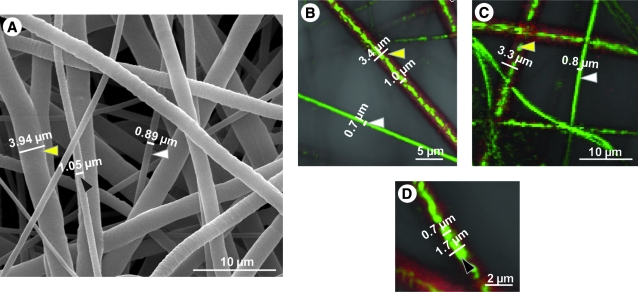

The study evaluated transverse dimensions of coaxial fiber morphology, that is, outer sheath of the fibers made from PCL and inner core made from PEG using confocal microscopy. These were clearly distinguished with the fluorescent markers used in the study as shown in Figure 2. Other methods of analysis such as transmission electron microscopy did not provide sufficient visualization of the core/sheath morphology in coaxial microfibers, although it has successfully been used previously for visualization of coaxial nanofibers.44 The sheath fibers appeared red due to the incorporation of DiI in the PCL solution, whereas the core fibers appeared green due to the incorporation of FITC in the PEG solution. Although the fluorescent markers were not covalently tagged to the polymers, evidence in the literature strongly indicates that mixing between the sheath and core solutions is minimal, thus confining the dyes to their respective polymers.44,45

FIG. 2.

Confocal microscopy and corresponding SEM images of the coaxial electrospun microfibers. The core of the coaxial fibers is an aqueous mixture of PEG and FITC (hence appears green in the confocal images), and the sheath is an organic mixture of PCL (3:1 CHCl3:CH3OH) and DiI (hence appears red). Yellow arrows represent sections of fibers not in focus, whereas the gray arrows are sections in focus. Images are labeled according to the combination of variables used (e.g., PWCn stands for high PCL wt%, high PEG MW, high PEG concentration, and low NaCl concentration). The scale bars represent 5 μm for confocal images and 10 μm for SEM images.

Variation in the distribution of fiber diameters

SEM analysis of the coaxial fiber meshes shows a significant change in the distribution of the fiber diameters as the sheath polymer (PCL) is increased in concentration from 9 to 11 wt% as indicated in Figures 2 and 3. Fibers made from 9 wt% PCL had a significant increase in the percentage distribution of submicron fibers (diameters <1 μm). The average population of submicron fibers increased from 3.0 ± 2.9% to 25.7 ± 8.1% when PCL concentration across all groups dropped from 11 to 9 wt%. Similarly, intermediate fibers with diameters between 1.1 and 2.0 μm increased from 4.8 ± 3.3% to 13.8 ± 5.0%. The prevalence of a population of significantly smaller fibers within coaxial fiber meshes have been widely reported in literature.46 Thus far, however, the composition of these fibers has been unknown. However, two theories have been proposed. Yu et al.45 suggested that these fibers are mainly composed of the core polymer and are formed when the charge density of the polymer solutions is high. The core polymer is extruded at a higher rate than the sheath polymer feed line can provide for entrainment. The other hypothesis states that sub-jets are formed from the sheath polymer solution during the process of electrospinning due to Maxwell's stresses29 acting on the polymer jet due to the surrounding electric field. This creates fibers that do not exhibit core/shell morphology and are composed of the shell polymer.

FIG. 3.

Distribution of coaxial electrospun PCL/PEG fibers. The percentage of submicron (<1 μm, red) and micron fibers >1 μm but <2 μm (yellow) increases when the PCL (sheath) concentration changes from 11 to 9 wt%. Fibers >2 μm in total diameter are represented in the orange sections of the bar graphs. The circles (●) represent the average diameter of the micron fiber >2 μm, triangles (▴) represent average diameter of fibers between 1 and 2 μm, and squares (▪) represent average fiber diameter of submicron fibers (<1 μm), each with their respective standard deviations.

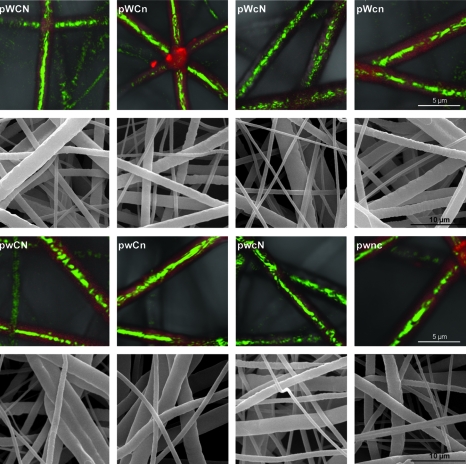

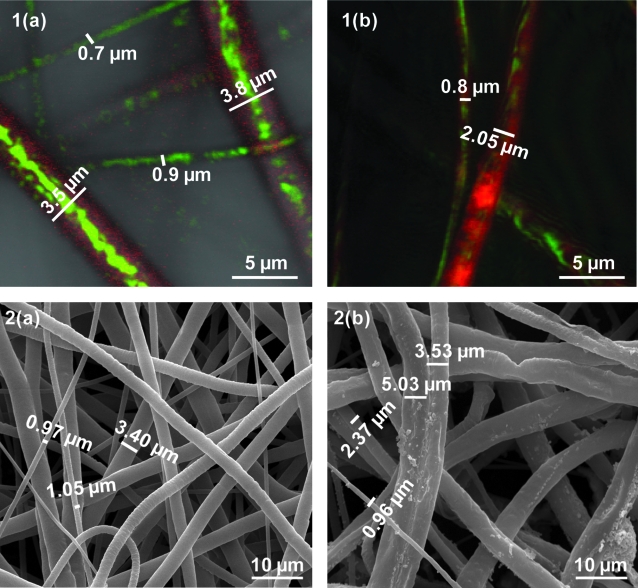

Confocal microscopy images of these fibers, as in Figure 4, show that the fibers <1 μm in diameter appear to be predominantly PEG (core) polymer. The potential presence of an undetected thin PCL sheath surrounding the predominantly PEG fibers could not be excluded due to the limited resolution of optical microscopy. Hence, two of the synthesized groups of 9 wt% PCL polymer fiber scaffolds were incubated in PBS for 3 days at 37°C on a shaker. SEM analysis of the fibers showed that there was on average a decrease in the population of submicron fibers (pWCn scaffolds decreased from 17.78 ± 2.34% to 11.44 ± 1.72%, whereas the pwcn scaffolds decreased from 30.11 ± 2.11% to 20.5 ± 1.68%) as noted in Table 2. Confocal microscopy analysis further suggests that the submicron fibers observed after 3 days of incubation in PBS had both PCL and PEG present within them as shown in Figure 5.

FIG. 4.

SEM (A) and confocal (B–D) images of 9 wt% coaxial electrospun PCL/PEG fibers displaying three populations of fibers based on coaxial morphology. Submicron fibers (<1 μm) (A, B, C) are indicated by white arrowheads. Fibers between 1 and 2 μm (A, D) have a thin PCL sheath and are largely comprised of PEG as indicated by the black arrowheads, and fibers >2 μm (A, B, C) comprise the majority of the population of the coaxial fibers and have a thicker sheath as indicated by the yellow arrowheads. Scale bars are indicated on their respective images.

Table 2.

Fiber Distribution and Average Diameters of Two Types (pWCn and pwcn) of Coaxial Fibers Made from 9 wt% PCL Before and After Incubation in PBS for 3 Days

| |

Day 0 |

Day 3 (after immersion in PBS) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 μm | 1–2 μm | >2 μm | <1 μm | 1–2 μm | >2 μm | |

| Group: pWCn | ||||||

| Average diameter (μm) | 0.65 ± 0.19 | 1.37 ± 0.29 | 3.42 ± 0.81 | 0.70 ± 0.18 | 1.44 ± 0.30 | 3.45 ± 0.80 |

| % Prevalence | 17.78 ± 2.34 | 17.90 ± 4.01 | 64.44 ± 3.89 | 11.44 ± 1.72 | 15.60 ± 3.90 | 74.36 ± 4.08 |

| Group: pwcn | ||||||

| Average diameter (μm) | 0.62 ± 0.13 | 1.64 ± 0.30 | 3.48 ± 0.85 | 0.64 ± 0.16 | 1.48 ± 0.30 | 3.41 ± 0.79 |

| % Prevalence | 31.11 ± 2.11 | 14.44 ± 1.89 | 54.44 ± 3.24 | 20.50 ± 1.68 | 15.50 ± 0.80 | 64.84 ± 3.44 |

FIG. 5.

Confocal [1(a) and 1(b)] and SEM [2(a) and 2(b)] images of coaxial fibers made from 9 wt% PCL before [1(a) and 2(a)] and after [1(b) and 2(b)] incubation in PBS for 3 days.

The intermediate fibers with diameters between 1.1 and 2.0 μm had a significantly increased PEG content as compared to the coaxial microfibers >2.0 μm (46.1–85.0% vs. 25.2–52.7%). The mechanism behind the formation of these submicron and intermediate fibers cannot be explained by the experiments described here. However, these data suggest that by increasing the sheath polymer concentration, the prevalence of submicron and intermediate fibers decreases significantly.

Influence of PCL sheath concentration on fiber morphology

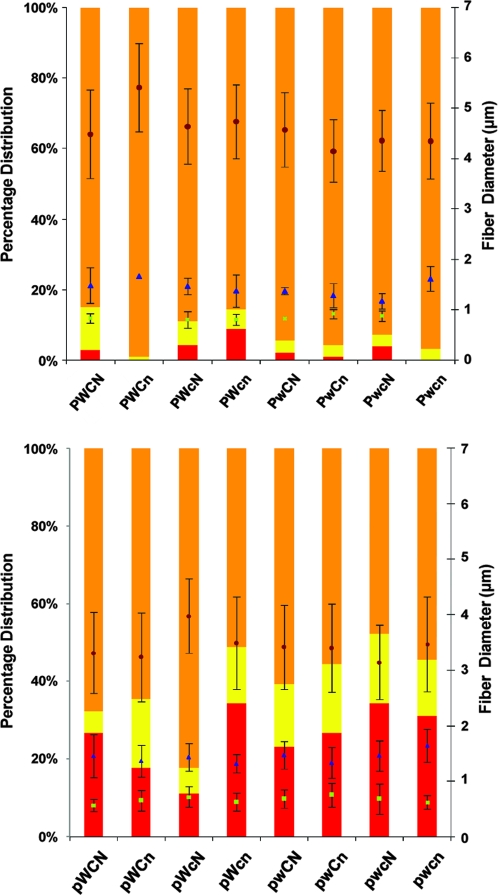

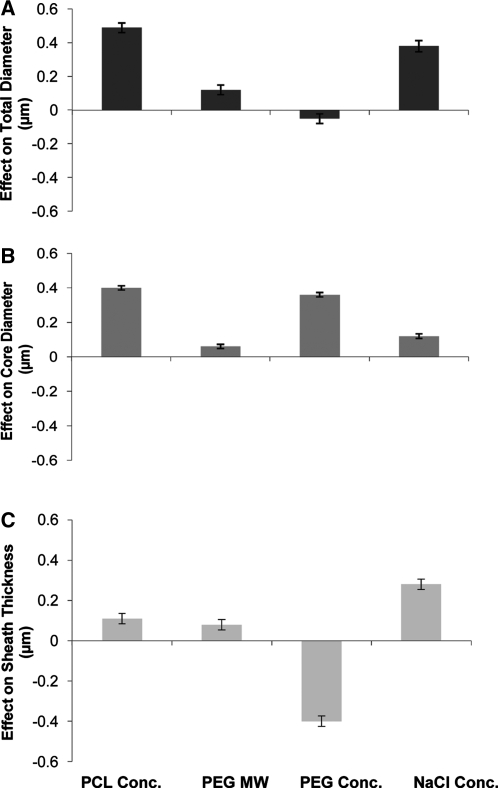

An additional goal of this study was to evaluate the influence of the different parameters listed in Table 1 on total and core diameter and sheath thickness. The high and low values of the parameters were selected on the condition that they produced continuous, uniform coaxial fibers. PCL concentration was evaluated at a low value of 9 wt% and a high value of 11 wt%, as shown in Table 1. Figure 6 and Table 3 show the influence of the PCL sheath concentration on total and core diameters, as well as sheath thicknesses with dimensions at low concentration treated as baselines. Hence, increasing the PCL concentration contributed to an increase in the total and core fiber diameters as well as the sheath thickness. The total diameter increased by 0.49 ± 0.03 μm, whereas the sheath diameter increased by 0.11 ± 0.03 μm. The data suggest that the core fiber diameters were also affected by the increase in PCL concentration; the mean increased by 0.40 ± 0.01 μm. The increase in thickness of the fiber sheaths due to an increase in sheath polymer concentration can be explained as an effect of increasing the viscosity of the polymer. However, the relatively greater effect on the overall fiber diameter as well as on the core fiber diameter requires further discussion.

FIG. 6.

Effect of the variable processing parameters, PCL concentration, PEG molecular weight, PEG concentration, and NaCl concentration within the core solution on total fiber diameter (A), core diameter (B), and sheath thickness (C). Error bars represent standard error. The tested parameters have a significant effect on the fiber total diameter, core diameter, or sheath thickness if their respective error bars do not cross the base line (x axis).52

Table 3.

Quantitative Summary of the Effect of Variable Parameters (PCL Concentration, PEG Molecular Weight, PEG Concentration, and NaCl Concentration) on Total Fiber Diameter, Core Diameter, and Sheath Thickness

| PCL concentration (μm) | PEG molecular weight (μm) | PEG concentration (μm) | NaCl concentration (μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total diameter | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | −0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.38 ± 0.03 |

| Core diameter | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| Sheath thickness | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | −0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

The increase in core diameters due to increase in PCL concentration could be an indirect effect related to the decreased prevalence of submicron fibers in meshes made from 11 wt% PCL formulations. Because the flow rate and hence the total core polymer supplied to the meshes remains constant, the core polymer either becomes part of submicron fibers (with 9 wt% PCL formulations) or gets embedded within the coaxial fibers (with 11 wt% PCL formulations). Thus, there is a significant increase in average core diameters (by 5.91 ± 0.22%) of fibers made from 11 wt% PCL. This increase in the core diameters further translates to an increase in the total diameter of the coaxial fibers.

Influence of PEG molecular weight on fiber morphology

Increasing the molecular weight of the core polymer moderately increases the total and core diameters as well as the sheath thickness. Molecular weight is a contributing factor to the viscosity of the polymer solution and possibly increases the overall viscosity of the polymer jets. For example, in our experience when the molecular weight of PEG is increased to 10,000 kDa, the polymers precipitate at the coaxial needle outlet. Upon increasing the PEG molecular weight, the total diameter of the fibers increases by 0.12 ± 0.02 μm, whereas the core diameter increases by 0.06 ± 0.01 μm, or 0.63 ± 0.31%. There is also a comparable increase in the sheath thickness (0.08 ± 0.03 μm) of the fibers. To our knowledge, thus far, studies have not looked at the influence of polymer molecular weights on coaxial fiber morphology. However, we can draw upon few studies that have addressed the influence on conventional fibers. A study by Koski et al.47 reported that increasing the molecular weight of poly(vinyl alcohol) increased the fiber diameter of conventional fibers from 200 nm to 2 μm. A similar study published by Eda et al.48 investigated the influence of a wider range (44,100, 393,400, and 1,877,000 g/mol) of molecular weights. Although none of the above concentrations produced uniform, bead-free fibers, the study reported a change in the electro-hydrodynamic cone jet properties that further resulted in the change in morphology of the polymer jet as well as the morphology of the fibers. Influences of a smaller range of molecular weights such as the ones tested here may be more subtle but still significant in affecting fiber diameters as reported here.

Influence of PEG concentration on fiber morphology

Increasing the PEG concentration from 200 to 400 mg/mL caused a significant effect on the morphology of the fibers. The total diameter of the fibers decreased by 0.05 ± 0.03 μm. The core fiber diameter increased by 0.36 ± 0.01 μm (9.89 ± 0.30%), whereas the sheath thickness decreased by 0.40 ± 0.30 μm. A study by Zhang et al.40 reported a similar increase in core diameters in coaxial fibers; however, they also reported an increase in the total diameters contrary to the results reported here. The main difference between these two studies is the dimensions of the fibers analyzed; while the study by Zhang et al. was testing nanofibers between 277 and 378 nm, this study is examining microfibers with average sheath thicknesses of 2.50 ± 0.35 μm. Zhang et al. have explained their results with the help of the swell effect of viscoelastic polymers, whereby the core fluid diameter enlarges after it is extruded from a narrow space, such as a needle. This swell effect of the core polymer translates to the fiber sheaths, which in turn increases the total diameter. The elasticity of the PEG and PCL may translate differently in microfibers than in nanofibers. In the case of fibers that have sheath thicknesses in the micrometer range, the swell effect may translate only to a few layers within the wall of the sheath polymer, causing their compression, which in turn provides more volume for the core polymer to expand. The finding that the sheath thickness decreases with an increase in the core polymer concentration further supports the theory that the core polymer compresses the inner sheath layers. The resulting sheath thickness versus the structural density profile of the coaxial sheath may play a significant role in the degradation kinetics of the fibers and the release of the molecules embedded within them.

Influence of NaCl concentration on fiber morphology

The influence of charge density on the behavior of polymer jets and consequently on fiber morphology is relatively well characterized in the literature in the context of conventional electrospinning.34,35 Charge densities of electrospun jets are attributed to the dielectric permittivity of the solvents or the conductivity of the polymers within them.48 Increasing the charge density by using a solvent with a higher dielectric constant, using a more conducting polymer, or increasing the electric current applied causes a decrease in the resultant fiber diameter.49,33 Adding salts such as palladium diacetate49 or NaCl33 also decreases the fiber diameter by increasing the conductivity and charge density. However, similar data on coaxial fibers are limited.

Contrary to results with conventional electrospinning, when 500 mM NaCl was added to the aqueous core PEG solution of the coaxial jet, the total and core diameters, as well as the sheath thicknesses, increased. The average increase in total diameter was 0.38 ± 0.03 μm, the core diameter increased by 0.12 ± 0.01 μm, whereas the sheath thickness increased by 0.28 ± 0.03 μm. Although these results seem counterintuitive, consideration of the theories proposed thus far with regard to conventional electrospinning can offer some insight. It is well known that the addition of salt increases the conductance of solvents, thereby increasing the dielectric constant of the solution. With conventional electrospinning models, increasing the conductance of the polymer increases the bending instability of the polymer jet. When radial Maxwell forces cause sufficient repulsion between the charges, the resultant jet splits, consequently forming fibers with smaller diameters.50 However, the electro-hydrodynamics in coaxial systems are more complex. Although similar Maxwell repulsive forces may be present within the charged core polymer, a less conductive PCL polymer sheath may mitigate these forces. Thus, in coaxial systems the charge repulsion may not overcome the cohesive forces and instead translates to larger fiber diameters. Characterization of the complex interactions involved in a coaxial system that are responsible for this phenomenon is beyond the scope of this study. Further elucidation with theoretical models for coaxial spinning, similar to those provided for conventional electrospinning by Reneker et al.33,51 and Rutledge et al.,35–37,42 among others, will be required to appreciate the complex electro–hydrodynamic interactions involved in coaxial systems.

Conclusion

The experiments described here evaluate the influence of various processing parameters on coaxial fiber morphology. The influence of sheath polymer (PCL) concentration, core polymer (PEG) concentration and molecular weight, and NaCl concentration within the core polymer on total and core fiber diameters and sheath thickness were tested using confocal microscopy. The results show that increasing PCL concentration and increasing NaCl concentration have the most influence of total fiber diameters. Core diameters are most influenced by PCL and PEG concentrations. Core polymer concentrations have a negative influence on sheath thicknesses, whereas NaCl concentration has maximal positive influence on sheath thickness. The information generated by these studies has the potential to facilitate the synthesis of coaxial fibers with tunable dimensions, which consequently may affect the release kinetics of the compounds embedded within them.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AR48756 and R21 AR56076). Anita Saraf would also like to acknowledge funding by NSF Grant DGE-0114264 and the Baylor College of Medicine, Medical Scientist Training Program.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ali A.A. New generation of super absorber nano-fibroses hybrid fabric by electro-spinning. J Mater Process Technol. 2008;199:193. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dersch R. Graeser M. Greiner A. Wendorff J.H. Electrospinning of nanofibres: towards new techniques, functions, and applications. Aust J Chem. 2007;60:719. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang Y.K. Park C.H. Kim J. Kang T.J. Application of electrospun polyurethane web to breathable water-proof fabrics. Fibers Polym. 2007;8:564. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan K. Obendorf S.K. Fabrication and evaluation of electrospun nanofibrous antimicrobial nylon 6 membranes. J Membr Sci. 2007;305:287. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg M. Langer R. Jia X.Q. Nanostructured materials for applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2007;18:241. doi: 10.1163/156856207779996931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenawy E.R. Abdel-Hay F.I. El-Newehy M.H. Wnek G.E. Controlled release of ketoprofen from electrospun poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibers. Mater Sci Eng A. 2007;459:390. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tungprapa S. Jangchud I. Supaphol P. Release characteristics of four model drugs from drug-loaded electrospun cellulose acetate fiber mats. Polymer. 2007;48:5030. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaseashta A. Stamatin I. Electrospun polymers for controlled release of drugs, vaccine delivery, and system-on-fibers. J Optoelectronic Adv Mater. 2007;9:1606. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang D.Z. Li Y.N. Nie J. Preparation of gelatin/PVA nanofibers and their potential application in controlled release of drugs. Carbohydr Polym. 2007;69:538. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong Y. Fujimoto K. Hashizume R. Guan J. Stankus J.J. Tobita K. Wagner W.R. Generating elastic, biodegradable polyurethane/poly(lactide-co-glycolide) fibrous sheets with controlled antibiotic release via two-stream electrospinning. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1200. doi: 10.1021/bm701201w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Y.S. Yang D.Z. Chen X.M. Xu Q. Lu F.M. Nie J. Electrospun water-soluble carboxyethyl chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibrous membrane as potential wound dressing for skin regeneration. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:349. doi: 10.1021/bm7009015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim G.H. Yoon H. A direct-electrospinning process by combined electric field and air-blowing system for nanofibrous wound-dressings. Appl Physiol A. 2008;90:389. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J.P. Chang G.Y. Chen J.K. Electrospun collagen/chitosan nanofibrous membrane as wound dressing. Colloid Surf A. 2008;313:183. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duan Y.Y. Jia J. Wang S.H. Yan W. Jin L. Wang Z.Y. Preparation of antimicrobial poly(epsilon-caprolactone) electrospun nanofibers containing silver-loaded zirconium phosphate nanoparticles. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;106:1208. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han I. Shim K.J. Kim J.Y. Im S.U. Sung Y.K. Kim M. Kang I.K. Kim J.C. Effect of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) nanofiber matrices cocultured with hair follicular epithelial and dermal cells for biological wound dressing. Artif Organs. 2007;31:801. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2007.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva S.Y. Rueda L.C. Marquez G.A. Lopez M. Smith D.J. Calderon C.A. Castillo J.C. Matute J. Rueda-Clausen C.F. Orduz A. Silva F.A. Kampeerapappun P. Bhide M. Lopez-Jaramillo P. Double blind, randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers, using a nitric oxide releasing patch: PATHON. Trials. 2007;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li W.S. Guo Y. Wang H. Shi D.J. Liang C.F. Ye Z.P. Qing F. Gong J. Electrospun nanofibers immobilized with collagen for neural stem cells culture. J Mater Sci. 2008;19:847. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moroni L. Schotel R. Hamann D. de Wijn J.R. van Blitterswijk C.A. 3D fiber-deposited electrospun integrated scaffolds enhance cartilage tissue formation. Adv Funct Mater. 2008;18:53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell H.M. Boyce S.T. Fiber density of electrospun gelatin scaffolds regulates morphogenesis of dermal-epidermal skin substitutes. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;84A:1078. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews K.D. Hunt J.A. Black R.A. Technology of electrostatic spinning for the production of polyurethane tissue engineering scaffolds. Polym Int. 2008;57:203. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srouji S. Kizhner T. Suss-Tobi E. Livne E. Zussman E. 3-D Nanofibrous electrospun multilayered construct is an alternative ECM mimicking scaffold. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19:1249. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3218-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mieszawska A.J. Jalilian R. Sumanasekera G.U. Zamborini F.P. The synthesis and fabrication of one-dimensional nanoscale heterojunctions. Small. 2007;3:722. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin M. Zhang X.T. Nishimoto S. Liu Z.Y. Tryk D.A. Murakami T. Fujishima A. Large-scale fabrication of Ag nanoparticles in PVP nanofibres and net-like silver nanofibre films by electrospinning. Nanotech. 2007;18:75605. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/18/7/075605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nie H.M. Wang C.H. Fabrication and characterization of PLGA/HAp scaffolds for delivery of BMP-2 plasmid composite DNA. J Control Release. 2007;120:111. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu Y.C. Nie H. Ho M.L. Wang C.K. Wang C.H. Optimized bone regeneration based on sustained release from three-dimensional fibrous PLGA/HAp composite scaffolds loaded with BMP-2. Biotech Bioeng. 2008;99:996. doi: 10.1002/bit.21648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chew S.Y. Mi R.F. Hoke A. Leong K.W. Aligned protein-polymer composite fibers enhance nerve regeneration: a potential tissue-engineering platform. Adv Funct Mater. 2007;17:1288. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200600441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng J. Yang L. Liang Q. Zhang X. Guan H. Xu X. Chen X. Jing X. Influence of the drug compatibility with polymer solution on the release kinetics of electrospun fiber formulation. J Control Release. 2005;105:43. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi H.X. Hu P. Xu J. Wang A.J. Encapsulation of drug reservoirs in fibers by emulsion electrospinning: morphology characterization and preliminary release assessment. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2327. doi: 10.1021/bm060264z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y.Z. Wang X. Feng Y. Li J. Lim C.T. Ramakrishna S. Coaxial electrospinning of (fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated bovine serum albumin)-encapsulated poly(epsilon-caprolactone) nanofibers for sustained release. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1049. doi: 10.1021/bm050743i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang H. Hu Y. Zhao P. Li Y. Zhu K. Modulation of protein release from biodegradable core-shell structured fibers prepared by coaxial electrospinning. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2006;79:50. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao I.C. Chew S.Y. Leong K.W. Aligned core-shell nanofibers delivering bioactive proteins. Future Med. 2006;1:465. doi: 10.2217/17435889.1.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deitzel J.M. Kleinmeyer J. Harris D. Tan N.C.B. The effect of processing variables on the morphology of electrospun nanofibers and textiles. Polymer. 2001;42:261. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson C.J. Chase G.G. Yarin A.L. Reneker D.H. Effects of parameters on nanofiber diameter determined from electrospinning model. Polymer. 2007;48:6913. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zong X.H. Kim K. Fang D.F. Ran S.F. Hsiao B.S. Chu B. Structure and process relationship of electrospun bioabsorbable nanofiber membranes. Polymer. 2002;43:4403. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hohman M.M. Shin M. Rutledge G. Brenner M.P. Electrospinning and electrically forced jets. I. Stability theory. Phys Fluids. 2001;13:2201. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hohman M.M. Shin M. Rutledge G. Brenner M.P. Electrospinning and electrically forced jets. II. Applications. Phys Fluids. 2001;13:2221. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shin Y.M. Hohman M.M. Brenner M.P. Rutledge G.C. Experimental characterization of electrospinning: the electrically forced jet and instabilities. Polymer. 2001;42:9955. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casper C.L. Stephens J.S. Tassi N.G. Chase D.B. Rabolt J.F. Controlling surface morphology of electrospun polystyrene fibers: effect of humidity and molecular weight in the electrospinning process. Macromolecules. 2004;37:573. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katti D.S. Robinson K.W. Ko F.K. Laurencin C.T. Bioresorbable nanofiber-based systems for wound healing and drug delivery: optimization of fabrication parameters. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2004;70:286. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang C. Zhang W. Huang Z.H. Yan E.Y. Su Y.H. Effect of concentration, voltage, take-over distance and diameter of pinhead on precursory poly (phenylene vinylene) electrospinning. Pigment Resin Tech. 2006;35:278. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y. Huang Z.M. Xu X. Lim C.T. Ramakrishna S. Preparation of core-shell structured PCL-r-gelatin bi-component nanofibers by coaxial electrospinning. Chem Mater. 2004;16:3406. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang M. Yu J.H. Kaplan D.L. Rutledge G.C. Production of submicron diameter silk fibers under benign processing conditions by two-fluid electrospinning. Macromolecules. 2006;39:1102. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pham Q.P. Sharma U. Mikos A.G. Electrospun poly(epsilon-caprolactone) microfiber and multilayer nanofiber/microfiber scaffolds: characterization of scaffolds and measurement of cellular infiltration. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2796. doi: 10.1021/bm060680j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun Z.E. Zussman A.L. Yarin J.H. Wendorff G.A. Compound core-shell polymer nanofibers by co-electrospinning. Adv Mater. 2003;15:1929. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu J.H. Fridrikh S.V. Rutledge G.C. Production of submicrometer diameter fibers by two-fluid electrospinning. Adv Mater. 2004;16:1562. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang Z.M. He C.L. Yang A. Zhang Y. Han X.J. Yin J. Wu Q. Encapsulating drugs in biodegradable ultrafine fibers through co-axial electrospinning. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77:169. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koski A. Yim K. Shivkumar S. Effect of molecular weight on fibrous PVA produced by electrospinning. Mater Lett. 2004;58:493. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eda G. Liu J. Shivkumar S. Flight path of electrospun polystyrene solutions: effects of molecular weight and concentration. Mater Lett. 2007;61:1451. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fridrikh S.V. Yu J.H. Brenner M.P. Rutledge G.C. Controlling the fiber diameter during electrospinning. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90:144502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.144502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hou H. Jun Z. Reuning A. Schaper A. Wendorff J.H. Greiner A. Poly(p-xylylene) nanotubes by coating and removal of ultrathin polymer template fibers. Macromolecules. 2002;35:2429. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reneker D.H. Chun I. Nanometre diameter fibres of polymer, produced by electrospinning. Nanotech. 1996;7:216. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rueda N. Bacaud R. Lanteri P. Vrinat M. Factorial design for the evaluation of the influence of preparation parameters upon the properties of dispersed molybdenum sulfide catalysts. Appl Cat A. 2001;215:81. [Google Scholar]