Abstract

Iatrogenic bile duct injuries (IBDI) remain an important problem in gastrointestinal surgery. They are most frequently caused by laparoscopic cholecystectomy which is one of the commonest surgical procedures in the world. The early and proper diagnosis of IBDI is very important for surgeons and gastroenterologists, because unrecognized IBDI lead to serious complications such as biliary cirrhosis, hepatic failure and death. Laboratory and radiological investigations play an important role in the diagnosis of biliary injuries. There are many classifications of IBDI. The most popular and simple classification of IBDI is the Bismuth scale. Endoscopic techniques are recommended for initial treatment of IBDI. When endoscopic treatment is not effective, surgical management is considered. Different surgical reconstructions are performed in patients with IBDI. According to the literature, Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy is the most frequent surgical reconstruction and recommended by most authors. In the opinion of some authors, a more physiological and equally effective type of reconstruction is end-to-end ductal anastomosis. Long term results are the most important in the assessment of the effectiveness of IBDI treatment. There are a few classifications for the long term results in patients treated for IBDI; the Terblanche scale, based on clinical biliary symptoms, is regarded as the most useful classification. Proper diagnosis and treatment of IBDI may avoid many serious complications and improve quality of life.

Keywords: Iatrogenic disease, Biliary drainage, Bile ducts, Cholecystectomy, Roux-en-Y anastomosis, Surgical injuries, Surgical anastomosis

INTRODUCTION

Iatrogenic bile duct injuries (IBDI) remain an important problem in gastrointestinal surgery. They are most frequently caused by laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which is one of the commonest surgical procedures in the world[1]. The early and accurate diagnosis of IBDI is very important for surgeons and gastroenterologists, because unrecognized IBDI lead to serious complications such as biliary cirrhosis, hepatic failure and death[2,3]. The choice of the appropriate treatment for IBDI is very important, because it may avoid these serious complications and improve quality of life in patients. Therefore, the question regarding the type of treatment for patients with IBDI is still a matter of debate. Initially, endoscopic treatment is recommended in patients with IBDI. When endoscopic techniques are not effective, different surgical reconstructions are performed[4,5]. The goal of surgical treatment is reconstruction to allow good bile flow to the alimentary tract. In order to achieve this goal, many techniques are used. There are some contradictory opinions on different surgical reconstructions in the literature.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES OF RECONSTRUCTIVE BILIARY SURGERY

Anatomic knowledge of the liver and bile ducts can be traced to Babylon in 2000 BC[6]. Gallstone disease has been found in one mummy from Amen of the 21st Dynasty. Historic notes from Mesopotamia, Greece, Egypt and Roma also show an occurrence of bile duct disease in ancient history[6]. The first surgical procedures performed on bile ducts were not complicated. In 1618, Fabricus removed gallstones. In 1867, Bobbs performed cholecystostomy. Cholecystostomies were also performed by Sims (1878), Kocher (1878) and Tait (1879)[6-8]. The first planned cholecystectomy in the world was performed by Langenbuch in 1882[6-9]. The first choledochotomy was performed by Couvoissier in 1890. Widespread use of surgical procedures on bile ducts was associated with occurrence of IBDI. The first iatrogenic bile duct injury was described by Sprengel in 1891. He also reported the first choledochoduodenostomy (ChD) for calculi (1891)[7,10]. In 1892, Doyenn reported the first choledochocholedochostomy for the same condition[7]. Cholecystoenterostomy to the colon was the first biliary-alimentary anastomosis and it was performed by Winiwater in 1881[7]. The first surgical reconstruction (“end-to-side” ChD) of IBDI was performed by Mayo in 1905[7]. The first Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) was described by Monprofit in 1908. Dahl noted Roux-en-Y HJ for surgical treatment of IBDI in 1909[7]. In 1969, Smith created a mucosal graft anastomosis in the repair of the damaged proximal bile duct[7]. In 1954, Hepp and Couinaud described the hilar plate and long extrahepatic course of the left hepatic duct. The left hepatic duct, after dissection of the hilar plate, was used in the repair of high strictures[7]. In 1948, Longmire and Sanford described a technique of finding of a branch of the left hepatic duct for anastomosis in the high biliary strictures. This technique was based on partial resection of the left hepatic lobe. In 1957, this technique was modified by Soulpaut and Couinaud. They described finding much larger ductal structures in the left lobe by following the round ligament to the origin of the 3rd segment duct[7]. In 1994, Hepp and Blumgart described a technique of hilar and intrahepatic biliary-enteric anastomosis[11].

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS OF IBDI

Etiology of IBDI

IBDI present about 95% of all benign biliary strictures[12,13]. Benign biliary strictures encompass a wide spectrum involving not only IBDI, but also biliary disorders caused by other pathogenetic factors. The main causes of benign biliary strictures are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main causes of benign biliary strictures

| Congenital strictures | Biliary atresia and congenital cysts |

| Bile duct injuries | Iatrogenic: postoperative, following endoscopic and percutaneous procedures |

| Following blunt or penetrating trauma of the abdomen | |

| Inflammatory strictures | Cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis |

| Mirizzi’s syndrome | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | |

| Chronic ulcer or diverticulum of the duodenum | |

| Abscess or inflammation of the liver or subhepatic region | |

| Parasitic, viral infection | |

| Toxic drugs | |

| Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | |

| Radiation-induced strictures | |

| Papillary stenosis |

There are two main groups of surgical procedures leading to IBDI. The first group involves surgical procedures performed on the biliary tract such as open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, choledochotomy and previous operations on bile ducts. The second group involves operations performed on other organs of the epigastrium such as gastric resection (most frequently the Billroth II partial gastric resection), hepatic resection and liver transplantation, pancreatic resections, biliary-enteric anastomoses, portacaval shunts, lymphadenectomy and other procedures within the hepato-duodenal ligament[12,13]. IBDI occur most frequently during cholecystectomy. Recently, the number of patients with IBDI has increased two-fold, which has been associated with widespread use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy[1]. The incidence of IBDI following open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy according to different authors in the literature is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Incidence of IBDI following cholecystectomy (%)

| Author | IBDI incidence following OC | IBDI incidence following LC |

| McMahon et al[14], 1995 | 0.2 | 0.81 |

| Strasberg et al[15], 1995 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Shea et al[16], 1996 | 0.19-0.29 | 0.36-0.47 |

| Targarona et al[17], 1998 | 0.6 | 0.95 |

| Lillemoe et al[18], 2000 | 0.3 | 0.4-0.6 |

| Gazzaniga et al[19], 2001 | 0.0-0.5 | 0.07-0.95 |

| Savar et al[20], 2004 | 0.18 | 0.21 |

| Moore et al[21], 2004 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Misra et al[22], 2004 | 0.1-0.3 | 0.4-0.6 |

| Gentileschi et al[23], 2004 | 0.0-0.7 | 0.1-1.1 |

| Kaman et al[24], 2006 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

IBDI: Iatrogenic bile duct injuries; OC: Open cholecystectomy; LC: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Pathogenesis of IBDI

There are several factors associated with an increased risk of IBDI. Coexisting acute or chronic inflammation around the gallbladder and hepato-duodenal ligament can increase the difficulty of the surgical procedure and increase the risk of IBDI. Other factors such as patient obesity, fat within the hepato-duodenal ligament, poor exposure and bleeding in the surgical area also increase the risk of IBDI. Poor prognostic factors are also male gender and long duration of symptoms before cholecystectomy.

Anatomical anomalies of the bile ducts and hepatic arteries significantly increase the risk of IBDI. The most frequent cause of IBDI is misidentification of the bile duct as the cystic duct in cases of anomalies of cystic duct insertion into the common hepatic duct. About 70%-80% of all IBDI are a consequence of misidentification of biliary anatomy before clipping, ligating and dividing structures[12,13,25,26]. Excessive dissection along the common bile duct margins during open cholecystectomy can lead to biliary stricture because of damage to the three o’clock and nine o’clock axial arteries and their branches to the pericholedochal plexus. According to the literature, distal IBDI are accompanied by damage of axial arteries (10%-15%) and proximal IBDI are usually associated with damage to the hepatic artery and its branches (40%-60%)[26-30].

Clinical presentation of IBDI

The common clinical symptoms are jaundice, fever, chills, and epigastric pain. The clinical presentation depends on the type of injury and is divided into two groups. In patients with bile leaks, bile is present in the closed-suction drain located in the subhepatic region. If the subhepatic region is not drained, subhepatic bile collection (biloma) or abscess develops. In these patients fever, abdominal pain and other signs of sepsis occur. Generally, jaundice is not observed in these patients because cholestasis does not appear. In the second group of patients with biliary strictures, jaundice caused by cholestasis is the commonest clinical symptom[12,13].

Diagnostics of IBDI

Laboratory and radiological investigations are used in diagnosis of IBDI. Among laboratory examinations, indicators of cholestasis and liver function play an important role: serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, alanine and aspartate aminotransferases. In patients with IBDI without complications, the liver is not damaged. Therefore, cholestasis indicators are increased but aminotransferases are not increased in these patients. Pathological levels of aminotransferases are present in cases of secondary biliary cirrhosis as a serious complication of unrecognized or improperly treated biliary injuries. In patients with secondary biliary cirrhosis, hypoalbuminemia and coagulation defects (prolonged prothrombin time) are observed. They are the most frequently used parameters of synthetic capacity of the liver. Imaging diagnostics in IBDI involve ultrasonography of the abdominal cavity, cholangiography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), computed tomography, and magnetic resonance-cholangiography. Ultrasonography of the abdominal cavity allows imaging of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts with measurement of the diameter of the common bile duct or common hepatic duct. It also shows biloma or intraabdominal abscesses in patients with bile leaks. Computed tomography is useful for more specific investigation in doubtful cases in patients with bile leaks. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography is useful in assessment of the bile tract proximal to the location of the damage. ERCP is a very useful method of investigation in imaging of damaged bile ducts and it allows the repair of small bile duct injuries by insertion of a biliary prosthesis. Magnetic resonance cholangiography is a sensitive (85%-100%) and non-invasive imaging modality for the biliary tract. Currently, it is the “gold standard” in preoperative diagnosis of IBDI in patients qualifying for surgical reconstruction[12,13,31,32].

Almost 85% of IBDI are not recognized during the primary iatrogenic surgical procedure[33]. According to the literature, only 15%-30% of IBDI are recognized during the initial operation[34]. According to other data, 70% of IBDI are diagnosed within 6 mo and 80% within 12 mo after the initial operation[31].

Classification of IBDI

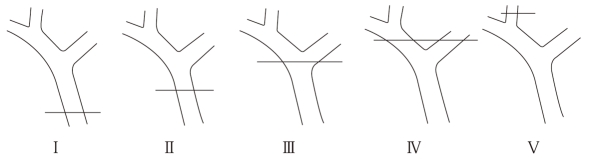

A number of classifications have been proposed by different authors. In our opinion, the Bismuth scale is the most useful and simple classification. It is based on the location of the injury in the biliary tract[35]. This classification is very helpful in prognosis after repair, but does not involve the wide spectrum of possible biliary injuries. The Bismuth classification is described in Figure 1. Another classification is the Strasberg scale which, in contrast to the Bismuth scale, allows differentiation between small (bile leakage from the cystic duct) and serious injuries performed during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but it does not play an important role in the choice of surgical treatment[15,34,36]. The Mattox classification of IBDI takes into consideration the type of injuring factor (contusion, laceration, perforation, transsection, diversion or interruption of the bile duct or the gallbladder)[37]. There are several classifications in the literature for IBDI induced during laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Stewart et al[38], Schmidt et al[27], Bektas et al[39]).

Figure 1.

Bismuth classification of IBDI. I: Common bile duct and low common hepatic duct (CHD) > 2 cm from hepatic duct confluence; II: Proximal CHD < 2 cm from the confluence; III: Hilar injury with no residual CHD-confluence intact; IV: Destruction of confluence: right and left hepatic ducts separated; V: Involvement of aberrant right sectoral hepatic duct alone or with concomitant injury of CHD.

MANAGEMENT OF IBDI

Endoscopic and radiological treatment of IBDI

Non-invasive, percutaneous radiological end endoscopic techniques are recommended as initial treatment of IBDI. When these techniques are not effective, surgical management is considered. According to the literature, the effectiveness of a radiological approach with transhepatic stenting of the damaged biliary tract is 40%-85%. The common complications of the radiological procedures are as follows: hemorrhage (hemobilia, bleeding from hepatic parenchyma or adjacent vessels), bile leakage and cholangitis. The other complications such as pneumothorax resulting from pleural violation, bilio-pleural fistula and perforation of adjacent abdominal structures including the gallbladder and large bowel, are described less frequently. Percutaneous dilatation is less effective (52%) than surgical treatment (89%). According to the literature, the radiological approach is also associated with a higher number of complications (35%) than surgical management (25%). Most frequently, it is recommended in very difficult cases of very high, hilar biliary strictures or in the treatment of very small diameter bile ducts[12,13,31,40].

Endoscopic dilatation associated with insertion of biliary prosthesis during ERCP investigation is the most frequently used non-surgical method in the treatment of IBDI. According to the literature, the success of endoscopic (72%) and surgical (83%) management of IBDI is comparable. Frequency of complications in both treatment methods is also comparable (35% vs 26%). The common complications of endoscopic techniques regarding placement of biliary prostheses include cholangitis, pancreatitis, prosthesis occlusion, migration, dislodgement and perforation of the bile duct. Endoscopic treatment is recommended as initial treatment of benign biliary strictures, in patients with biliary fistula or when surgical treatment is not warranted[12,13,41].

Surgical treatment of IBDI

The goal of surgical treatment is to reconstruct the bile duct to allow proper bile flow to the alimentary tract. In order to achieve this goal, many techniques are used. There are contradictory reports on the effectiveness of bile duct reconstruction methods in the literature. The following operations have been reported for surgical treatment of IBDI: Roux-en-Y HJ, end-to-end ductal biliary anastomosis (EE), ChD, Lahey HJ, jejunal interposition hepaticoduodenostomy, Blumgart (Hepp) anastomosis, Heinecke-Mikulicz biliary plastic reconstruction and Smith mucosal graft[11,18,42-46].

Various surgical techniques including immediate surgical repair: In the case of recognition of IBDI during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, immediate cholangiography and conversion to an open procedure in order to define the extent of the injury are required. The injury should be repaired by an experienced hepatobiliary surgeon. If this is impossible, a patient should be transferred to a hepatobiliary surgery referral center after adequate drainage of the subhepatic region. Bile ducts of diameter less than 2-3 mm without communication with a main biliary tract, should be ligated in order to avoid postoperative bile leak leading to development of biloma and abscess in the subhepatic region. Bile ducts of diameter more than 3-4 mm should be repaired, not ligated, because they drain a wider hepatic area. Interruption of common hepatic duct or common bile duct continuity can be repaired by immediate tension-free EE with or without a T tube, using absorbable sutures. Security of the immediately repaired bile duct with a T tube is controversial. According to the literature, in liver transplantation, EE over a T tube is associated with a significantly higher stricture rate than choledochocholedochostomy without a T tube (25% vs 11%). If the bile duct loss is too long and immediate and EE is not possible without tension, Roux-en-Y HJ is recommended[5,12,13,25,31,47].

Surgical reconstructions: A number of reconstructions are used in surgical treatment of IBDI. There are a few conditions for proper healing of each biliary anastomosis. The anastomosed edges should be healthy, without inflammation, ischemia or fibrosis. The anastomosis should be tension-free and properly vascularized. It should be performed in a single layer with absorbable sutures[25,38].

Currently, Roux-en-Y HJ is the most frequently performed surgical reconstruction of IBDI. In this surgical technique, a proximal common hepatic duct is identified and prepared and the distal common bile duct is sutured. End-to-side or end-to-end HJ is performed in a single layer using interrupted absorbable polydioxanone (PDS 4-0 or 5-0) sutures[48,49]. Most authors prefer HJ because of the lower number of postoperative anastomosis strictures. According to Terblanche et al[45], HJ is effective in 90% of cases. However, after this reconstruction, bile flow into the alimentary tract is not physiological, because the duodenum and upper part of the jejunum are excluded from bile passage. Physiological conditions within the proximal gastrointestinal tract are changed as a result of duodenal exclusion from bile passage. An altered bile pathway is a cause of disturbances in the release of gastrointestinal hormones[48-50]. There is a hypothesis that in patients with HJ, the bile bypass induces gastric hypersecretion leading to a pH change secondary to altered bile synthesis and release of gastrin. A higher number of duodenal ulcers is observed in patients with HJ, which may be associated with a loss of the neutralizing effect of the bile, including bicarbonates and secondary gastric hypersecretion[51]. Laboratory investigations revealed increased gastrin and glucagon-like immunoreactivity plasma levels and decreased triglycerides, gastric inhibitory polypeptide and insulin plasma levels in patients with HJ[51]. An altered pathway of bile flow is also a cause of disturbance in fat metabolism in patients undergoing HJ[51,52]. Moreover, the total surface of absorption in these patients is also decreased as a result of exclusion of the duodenum and upper jejunum from the passage of food. This hypothesis was supported by a study performed in our center. We compared early and long term results of two surgical reconstructions of IBDI: Roux-en-Y HJ and EE. The study showed a significantly lower weight gain in patients undergoing HJ in comparison to patients following physiological EE[49]. The other disadvantage of HJ is a lack of ability to control endoscopic examination and endoscopic dilatation of the strictured biliary anastomosis. In order to resolve this problem, a longer jejunal loop (jejunostomy) is prepared and sutured to the abdominal subcutaneous tissue in the right subcostal region. Jejunostomy can be open or closed with the possibility of opening in a case of biliary anastomosis stricture, which should be endoscopically dilated. Jejunostomy is associated with bile loss of about 40 mL/d[53].

EE is a physiological biliary reconstruction[49,54]. In this type of reconstruction, extensive mobilization of the duodenum with the pancreatic head through the Kocher maneuver, excision of the bile duct stricture, and refreshment of the proximal and distal stumps should be performed. Anastomosis is performed in a single layer with interrupted absorbable PDS 4-0 or 5-0 sutures[49]. This reconstruction is not recommended by most authors because of the higher number of anastomosis strictures in comparison with HJ. We recommend EE first, because in some patients, extensive mobilization of the duodenum with the pancreatic head by the Kocher maneuver allows tension-free anastomosis after the extensive bile duct length loss. Excision of the bile duct stricture, dissection and refreshing of the proximal and distal stumps as far as the tissues are healthy and without inflammation, and the use of non-traumatic, monofilament-interrupted 5-0 sutures allows the achievement of good long term results. Use of an internal Y tube conducting the right and left hepatic ducts into the duodenum through the EE and the papilla of Vater also allows the proper healing of this anastomosis. In our department, this reconstruction was performed when the bile duct loss was from 0.5 to 4 cm. It allowed the achievement of very good long term results with effectiveness comparable to HJ. Establishing a physiological bile pathway allows proper digestion and absorption, which causes a greater weight gain in patients following EE, as noted in our study[49]. Another essential advantage of EE is the possibility of control of the endoscopic examination in these patients. Fewer early complications are observed after EE than HJ, which is associated with opening of the alimentary tract and a higher number of anastomoses (biliary-enteric and entero-enteric)[49].

Other biliary reconstruction methods are used less frequently. ChD is actually a rarely performed operation recommended by some authors only in cases of injury within the distal portion of the common bile duct. It guarantees physiological bile flow into the duodenum and anastomosis endoscopic control, as well as being technically easier. It is recommended in some cases of distal strictures, when use of the jejunal loop, as a result of numerous adhesions, is impossible. It should be performed on the large common bile duct (> 15 mm diameter) because the postoperative strictures are more frequent within the narrow duct. ChD should be created between the duodenum and the distal common bile duct in order to decrease the risk of so-called sump syndrome noted in 0.14%-3.3% of cases in the literature. Following ChD, recurrent ascending cholangitis because of bile reflux is noted in 0%-4% of patients[11,31]. A higher rate of bile duct cancer in patients with ChD in comparison to HJ was noted by Tocchi et al[55] during a 30-year observation period (7.6% vs 1.9%).

Jejunal interposition hepaticoduodenostomy, using 25-35 cm of the jejunal loop, is performed in some surgical centers. This reconstruction includes three types of anastomosis (biliary-enteric, enteric-duodenal and entero-enteric). Biliary-enteric anastomosis is performed in a single layer with interrupted absorbable 5-0 sutures and enteric-duodenal anastomosis in a single layer with interrupted or continuous absorbable 4-0 sutures. The advantage of this reconstruction is physiological bile flow into the duodenum, which prevents duodenal ulcers caused by changes in the neurohormonal axis within the upper alimentary tract[10,56].

The repair of hilar IBDI requires special surgical techniques. In the past, the so-called “mucosal graft technique” described by Smith in the 1960s was performed[57,58]. This reconstruction involves creating a mucosal dome of jejunum (by removing a seromuscular patch) near the end of the Roux-en-Y loop through which a straight rubber tube is passed via hepatic ducts and through the liver parenchyma. This technique is based on the hypothesis that the jejunal mucosa grafts to the biliary epithelium, and a mucosa-to-mucosa anastomosis is created. Short-term results were good, but in the long term a high number of anastomosis strictures was observed. Therefore, currently, not Smith but the Blumgart-Hepp technique is used in reconstruction of hilar IBDI. In this technique, the dorsal surface of the left hepatic duct is placed parallel to the quadrate hepatic lobe; dissection and opening of the left hepatic duct longitudinally allows creation of a wide anastomosis of 1-3 cm in diameter[11,25,57-60].

Biliary drainage: There are several methods of biliary drainage securing the anastomosis: external T tube, external Y tube, Rodney Smith drainage and internal Y tube. External T drainage involves using a typical Kehr tube with insertion of its short branches into the bile duct and passage of its long branch through the abdominal wall to the outside. Y drainage involves insertion of short branches of the Kehr tube into both right and left hepatic ducts, splinting of the anastomosis and passage of its long branch through the jejunal loop and abdominal wall to the outside (external Y drainage) or into the duodenum by the papilla of Vater (internal Y drainage). An external T or Y tube is removed percutaneously and an internal Y tube is removed endoscopically. Most frequently, external T drainage is used in biliary-enteric anastomosis and internal Y drainage in EE. In Rodney Smith drainage, two straight rubber tubes splinting the biliary-enteric anastomosis are passed via the hepatic ducts, through the liver parenchyma and through the abdominal wall to the outside. This drainage type is used in high intrahilar biliary-enteric anastomosis. In the past, it was used in the Smith “mucosal graft technique”[54,58-60].

The use and duration of biliary drainage is still controversial. The advantage of biliary drainage is limitation of the inflammation and fibrosis occurring after the surgical procedure. In the opinion of some authors, the presence of the biliary tube prevents anastomosis stricture[61]. The disadvantage of biliary drainage is a higher risk of postoperative complications[62]. Mercado et al[63] recommend using transanastomotic stents when there is a thin bile duct less than 4 mm in diameter, and when there is inflammation within the ductal anastomosed edges which makes proper healing of the anastomosis questionable. The duration of drainage is also controversial. According to most authors, the optimal length of time for biliary drainage is about 3 mo. Investigations showed that longer durations of biliary drainage do not provide any advantage[18,64].

RESULTS OF SURGICAL TREATMENT OF IBDI

Short-term results and early complications

According to most authors, the early postoperative morbidity rate is 20%-30% and mortality rate 0%-2%[31,42,44]. The most frequent early complication is wound infection, which is described in 8%-17.7%[32,48,60,65]. Other complications reported in the literature are the following: bile collection, intra-abdominal abscess, biliary-enteric anastomosis dehiscence, biliary fistula, cholangitis, peritonitis, eventration, pneumonia, circulatory insufficiency, intra-abdominal bleeding, sepsis, infection of the urinary tract, pneumothorax, acute pancreatitis, thrombosis and embolic complications, diarrhea, ileus and multi-organ insufficiency[18,32,42,66].

Long term results

Assessment of long term results is the most important in surgical treatment of IBDI. Proof of successful surgical treatment is the absence of biliary anastomosis stricture. In referral centers, a successful outcome after surgical repair of IBDI is observed in 70%-90% of patients[3,5,45]. Two-thirds (65%) of recurrent biliary strictures develop within 2-3 years after the reconstruction, 80% within 5 years, and 90% within 7 years. Recurrent strictures 10 years after the surgical procedure are also described in the literature[3,31,67]. A satisfactory length of follow-up, which is necessary in order to assess the long term results of the repair procedure, is 2-5 years[18,31,64]. Some authors recommend 10 or 20 years of observation[43,45].

There are a number of classifications in order to assess the long term outcomes of bile duct surgical repairs. In our opinion, the Terblanche clinical grading (1990) is the most useful classification. It is based on clinical biliary symptomatology and is presented in Table 3[45]. Other less frequently used classifications by Nielubowicz et al[68] (1973), Lygidakis et al[69] (1986), Muñoz et al[70] (1990) and McDonald et al[66] (1995) are described in the literature.

Table 3.

Terblanche clinical classification for assessment of long-term results of surgical bile duct repair

| Grade | Result | |

| I | Excellent | No biliary symptoms with normal liver function |

| II | Good | Transitory symptoms, currently no symptoms and normal liver function |

| III | Fair | Clearly related symptoms requiring medical therapy and/or deteriorating liver function |

| IV | Poor | Recurrent stricture requiring correction, or related death |

CONCLUSION

Surgical procedures performed within the biliary tract are very common. The incidence of IBDI has increased recently, and has been associated with increased use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy worldwide. It is essential to be careful in the proper visualization of the surgical area and the identification of structures before ligation or transsection in order to decrease the risk of bile duct injuries during surgery. When biliary injury develops, early recognition and appropriate treatment are most important. Early and correct treatment allows avoidance of serious complications in patients with IBDI. Following bile duct repair, patients require long term and careful postoperative observation because of the possibility of biliary anastomosis stricture.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Ibrahim A Al Mofleh, Professor, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University, PO Box 2925, Riyadh 11461, Saudi Arabia

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Archer SB, Brown DW, Smith CD, Branum GD, Hunter JG. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a national survey. Ann Surg. 2001;234:549–558; discussion 558-559. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Negi SS, Sakhuja P, Malhotra V, Chaudhary A. Factors predicting advanced hepatic fibrosis in patients with postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures. Arch Surg. 2004;139:299–303. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellegrini CA, Thomas MJ, Way LW. Recurrent biliary stricture. Patterns of recurrence and outcome of surgical therapy. Am J Surg. 1984;147:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tocchi A, Mazzoni G, Liotta G, Costa G, Lepre L, Miccini M, De Masi E, Lamazza MA, Fiori E. Management of benign biliary strictures: biliary enteric anastomosis vs endoscopic stenting. Arch Surg. 2000;135:153–157. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davids PH, Tanka AK, Rauws EA, van Gulik TM, van Leeuwen DJ, de Wit LT, Verbeek PC, Huibregtse K, van der Heyde MN, Tytgat GN. Benign biliary strictures. Surgery or endoscopy? Ann Surg. 1993;217:237–243. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199303000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beal JM. Historical perspective of gallstone disease. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984;158:181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braasch JW. Historical perspectives of biliary tract injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:731–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy KJ. Carl Langenbuch and the Lazarus Hospital: events and circumstances surrounding the first cholecystectomy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1993;63:56–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1993.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Gulik TM. Langenbuch's cholecystectomy, once a remarkably controversial operation. Neth J Surg. 1986;38:138–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Górka Z, Ziaja K, Nowak J, Lampe P, Wojtyczka A. Biliary handicap. Pol Przeg Chir. 1992;64:969–976. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumgart LH. Hilar and intrahepatic biliary enteric anastomosis. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:845–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD, Ahrendt SA, Pitt HA. Operative management of strictures and benign obstructive disorders of the bile duct. In: Zuidema GD, Yeo CJ, Orringer MB, editors. Shackelford's surgery of the alimentary tract, Vol 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2002. pp. 247–261. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarnagin WR, Blumgart LH. Benign biliary strictures. In: Blumgart LH, Fong Y, editors. Surgery of the liver and biliary tract. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2002. pp. 895–929. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon AJ, Fullarton G, Baxter JN, O'Dwyer PJ. Bile duct injury and bile leakage in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:307–313. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shea JA, Healey MJ, Berlin JA, Clarke JR, Malet PF, Staroscik RN, Schwartz JS, Williams SV. Mortality and complications associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 1996;224:609–620. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199611000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Targarona EM, Marco C, Balagué C, Rodriguez J, Cugat E, Hoyuela C, Veloso E, Trias M. How, when, and why bile duct injury occurs. A comparison between open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:322–326. doi: 10.1007/s004649900662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, Sauter PA, Coleman J, Yeo CJ. Postoperative bile duct strictures: management and outcome in the 1990s. Ann Surg. 2000;232:430–441. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gazzaniga GM, Filauro M, Mori L. Surgical treatment of iatrogenic lesions of the proximal common bile duct. World J Surg. 2001;25:1254–1259. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savar A, Carmody I, Hiatt JR, Busuttil RW. Laparoscopic bile duct injuries: management at a tertiary liver center. Am Surg. 2004;70:906–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore DE, Feurer ID, Holzman MD, Wudel LJ, Strickland C, Gorden DL, Chari R, Wright JK, Pinson CW. Long-term detrimental effect of bile duct injury on health-related quality of life. Arch Surg. 2004;139:476–481; discussion 481-482. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misra S, Melton GB, Geschwind JF, Venbrux AC, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD. Percutaneous management of bile duct strictures and injuries associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a decade of experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gentileschi P, Di Paola M, Catarci M, Santoro E, Montemurro L, Carlini M, Nanni E, Alessandroni L, Angeloni R, Benini B, et al. Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a 1994-2001 audit on 13,718 operations in the area of Rome. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:232–236. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8815-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaman L, Sanyal S, Behera A, Singh R, Katariya RN. Comparison of major bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open cholecystectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:788–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connor S, Garden OJ. Bile duct injury in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93:158–168. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flum DR, Cheadle A, Prela C, Dellinger EP, Chan L. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy and survival in medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2003;290:2168–2173. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt SC, Settmacher U, Langrehr JM, Neuhaus P. Management and outcome of patients with combined bile duct and hepatic arterial injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2004;135:613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koffron A, Ferrario M, Parsons W, Nemcek A, Saker M, Abecassis M. Failed primary management of iatrogenic biliary injury: incidence and significance of concomitant hepatic arterial disruption. Surgery. 2001;130:722–728; discussion 728-731. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buell JF, Cronin DC, Funaki B, Koffron A, Yoshida A, Lo A, Leef J, Millis JM. Devastating and fatal complications associated with combined vascular and bile duct injuries during cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 2002;137:703–708; discussion 708-710. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jabłońska B. The arterial blood supply of the extrahepatic biliary tract - surgical aspects. Pol J Surg. 2008;80:336–342. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall JG, Pappas TN. Current management of biliary strictures. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:1098–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sikora SS, Pottakkat B, Srikanth G, Kumar A, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Postcholecystectomy benign biliary strictures - long-term results. Dig Surg. 2006;23:304–312. doi: 10.1159/000097894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Wit LT, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ. Surgical management of iatrogenic bile duct injury. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;230:89–94. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gouma DJ, Obertop H. Management of bile duct injuries: treatment and long-term results. Dig Surg. 2002;19:117–122. doi: 10.1159/000052024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bismuth H, Majno PE. Biliary strictures: classification based on the principles of surgical treatment. World J Surg. 2001;25:1241–1244. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murr MM, Gigot JF, Nagorney DM, Harmsen WS, Ilstrup DM, Farnell MB. Long-term results of biliary reconstruction after laparoscopic bile duct injuries. Arch Surg. 1999;134:604–609; discussion 609-610. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.6.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mattox KL, Feliciano DV, Moore EE. Trauma. 3rd ed. Stamford, CT: Applenton&Lange; 1996. pp. 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart L, Way LW. Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Factors that influence the results of treatment. Arch Surg. 1995;130:1123–1128; discussion 1129. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430100101019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bektas H, Schrem H, Winny M, Klempnauer J. Surgical treatment and outcome of iatrogenic bile duct lesions after cholecystectomy and the impact of different clinical classification systems. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1119–1127. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pitt HA, Kaufman SL, Coleman J, White RI, Cameron JL. Benign postoperative biliary strictures. Operate or dilate? Ann Surg. 1989;210:417–425; discussion 426-427. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198910000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vitale GC, Tran TC, Davis BR, Vitale M, Vitale D, Larson G. Endoscopic management of postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:918–923; discussion 924-925. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sicklick JK, Camp MS, Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Yeo CJ, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, Pitt HA, Coleman J, Sauter PA, et al. Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241:786–792; discussion 793-795. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161029.27410.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tocchi A, Costa G, Lepre L, Liotta G, Mazzoni G, Sita A. The long-term outcome of hepaticojejunostomy in the treatment of benign bile duct strictures. Ann Surg. 1996;224:162–167. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199608000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahrendt SA, Pitt HA. Surgical therapy of iatrogenic lesions of biliary tract. World J Surg. 2001;25:1360–1365. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terblanche J, Worthley CS, Spence RA, Krige JE. High or low hepaticojejunostomy for bile duct strictures? Surgery. 1990;108:828–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaudhary A, Chandra A, Negi SS, Sachdev A. Reoperative surgery for postcholecystectomy bile duct injuries. Dig Surg. 2002;19:22–27. doi: 10.1159/000052001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thethy S, Thomson BNj, Pleass H, Wigmore SJ, Madhavan K, Akyol M, Forsythe JL, James Garden O. Management of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:647–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jabłońska1 B, Lampe1 P, Olakowski1 M, Lekstan1 A, Górka Z. Surgical treatment of iatrogenic biliary injuries - early complications. Pol J Surg. 2008;80:299–305. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jabłońska B, Lampe P, Olakowski M, Górka Z, Lekstan A, Gruszka T. Hepaticojejunostomy vs. end-to-end biliary reconstructions in the treatment of iatrogenic bile duct injuries. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1084–1093. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rudnicki M, McFadden DW, Sheriff S, Fischer JE. Roux-en-Y jejunal bypass abolishes postprandial neuropeptide Y release. J Surg Res. 1992;53:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(92)90004-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nielsen ML, Jensen SL, Malmstrøm J, Nielsen OV. Gastrin and gastric acid secretion in hepaticojejunostomy Roux-en-Y. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1980;150:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Imamura M, Takahashi M, Sasaki I, Yamauchi H, Sato T. Effects of the pathway of bile flow on the digestion of fat and the release of gastrointestinal hormones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:386–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barker EM, Winkler M. Permanent-access hepaticojejunostomy. Br J Surg. 1984;71:188–191. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800710307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Górka Z, Ziaja K, Wojtyczka A, Kabat J, Nowak J. End-to- end anastomosis as a method of choice in surgical treatment of selected cases of biliary handicap. Pol J Surg. 1992;64:977–979. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tocchi A, Mazzoni G, Liotta G, Lepre L, Cassini D, Miccini M. Late development of bile duct cancer in patients who had biliary-enteric drainage for benign disease: a follow-up study of more than 1,000 patients. Ann Surg. 2001;234:210–214. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200108000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wheeler ES, Longmire WP Jr. Repair of benign stricture of the common bile duct by jejunal interposition choledochoduodenostomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146:260–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wexler MJ, Smith R. Jejunal mucosal graft: a sutureless technic for repair of high bile duct strictures. Am J Surg. 1975;129:204–211. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(75)90299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith R. Hepaticojejunostomy with transhepatic intubation: a technique for very high strictures of the hepatic ducts. Br J Surg. 1964;51:186–194. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800510307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jarnagin WR, Blumgart LH. Operative repair of bile duct injuries involving the hepatic duct confluence. Arch Surg. 1999;134:769–775. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.7.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Warren KW, Jefferson MF. Prevention and repair of strictures of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Surg Clin North Am. 1973;53:1169–1190. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)40145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidt SC, Langrehr JM, Hintze RE, Neuhaus P. Long-term results and risk factors influencing outcome of major bile duct injuries following cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:76–82. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robinson TN, Stiegmann GV, Durham JD, Johnson SI, Wachs ME, Serra AD, Kumpe DA. Management of major bile duct injury associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1381–1385. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Cano-Gutiérrez G, Chaparro JM, Galindo E, Vilatobá M, Samaniego-Arvizu G. To stent or not to stent bilioenteric anastomosis after iatrogenic injury: a dilemma not answered? Arch Surg. 2002;137:60–63. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lillemoe KD, Martin SA, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Talamini MA, Kaushal S, Coleman J, Venbrux AC, Savader SJ, Osterman FA, et al. Major bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Follow-up after combined surgical and radiologic management. Ann Surg. 1997;225:459–468; discussion 468-471. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199705000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bismuth H, Franco D, Corlette MB, Hepp J. Long term results of Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McDonald ML, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, Ilstrup DM, Kutch JM. Benign biliary strictures: repair and outcome with a contemporary approach. Surgery. 1995;118:582–590; discussion 590-591. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pitt HA, Miyamoto T, Parapatis SK, Tompkins RK, Longmire WP Jr. Factors influencing outcome in patients with postoperative biliary strictures. Am J Surg. 1982;144:14–21. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nielubowicz J, Olszewski K, Szostek M. [Reconstructive bile tract surgery ] Pol Przegl Chir. 1973;45:1389–1395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lygidakis NJ, Brummelkamp WH. Surgical management of proximal benign biliary strictures. Acta Chir Scand. 1986;152:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Muñoz R, Cárdenas S. Thirty years' experience with biliary tract reconstruction by hepaticoenterostomy and transhepatic T tube. Am J Surg. 1990;159:405–410. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]