Abstract

Two-dimensional Southwestern blotting (2D-SW) described here combines several steps. Proteins are separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose (NC) or polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The blotted proteins are then partially renatured and probed with a specific radiolabeled oligonucleotide for Southwestern blotting (SW) analysis. The detected proteins are then processed by on-blot digestion and identified by LC-MS/MS analysis. A transcription factor, bound by a specific radiolabeled element, is thus characterized without aligning with protein spots on a gel. In this study, we systematically optimize conditions for 2D-SW and on-blot digestion. By quantifying the SW signal using a scintillation counter, the optimal conditions for SW were determined to be: PVDF membrane, 0.5% PVP40 for membrane blocking, serial dilution of guanidine HCl for denaturing and renaturing proteins on the blot, and an SDS stripping buffer to remove radiation from the blot. By quantifying the peptide yields using nano-ESI-MS analysis, the optimized conditions for on-blot digestions were found to be: 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16 and 30% acetonitrile in trypsin digestion buffer. Using the optimized 2D-SW technique and on-blot digestion combined with HPLC-nano-ESI-MS/MS, a GFP-C/EBP model protein was successfully characterized from a bacterial extract, and native C/EBP beta was identified from 100 Eg HEK293 nuclear extract without any previous purification.

Keywords: Transcription factor, 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis, southwestern blot, mass spectrometry

1.0 INTRODUCTION

The purification and characterization of transcription factors is challenging. Transcription factors bind to specific DNA sequence elements in the promoters of genes, activating or repressing gene transcription. They are often present at low copy number (ranging between 103 and 105 molecules per cell) and hence nuclear extracts often contain very low concentrations of any one transcription factor. If 1 pmol of pure protein is required for successful LC-MS/MS characteization, a transcription factor (103–105 molecules per cell) would require isolation from 2 × 107–109 cells. Since yield is seldom 100%, purification often requires large amounts of starting material and successful characterization requires sensitive analytical methods. Proteomic identification methods, combining trypsin digestion and subsequent mass and sequence identification using capillary chromatography, nanospray electrospray ionization (NSI), and tandem mass spectrometry, provides the necessary sensitivity and can provide reliable identity and sequence information at the subpicomole level 1, 2.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis is a particularly appealing method for fractionation of nuclear extract or partially purified proteins. Fractionating proteins by isoelectric focusing in a first dimension and then by molecular mass in a second dimension, about 5000 proteins can be separated on a single gel 3, 4. This could then be combined with the Southwestern blotting technique to identify the transcription factor of interest. The SW was first described by Bowen et al early in 1980 5, and is used to identify and characterize DNA-binding proteins that interact with DNA in a sequence-specific manner. In a SW, the proteins are separated by gel electrophoresis and then electroblotted, typically to nitrocellulose (NC) or polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. After partial renaturation of the proteins on the blot, a radiolabeled oligonucleotide containing the DNA response element is incubated with the membrane and binds the transcription factor on the blot. Autoradiography then reveals its location. The success of SW largely depends on the successful renaturation of the proteins after their separation. Some DNA-binding proteins may be inefficiently renatured, resulting in inefficient binding by DNA on membrane. In addition, any multimeric protein that requires a combination of different subunits or cofactor(s) to bind DNA may be difficult to detect by this technique 6, 7. Despite these limitations, SW analysis provides sensitive and specific detection when applicable. In this study, the conditions for SW analysis are optimized systematically.

SW would be particularly appealing if it could be combined with on-blot trypsin digestion so that samples could be directly applied to the mass spectrometer for characterization. On-blot digestion is an alternative to in-gel digestion for better digestion efficiency and sequence coverage, and has been used to analyze intact proteins electroblotted to NC or PVDF membranes for immunostaining analysis 8.

To test the feasibility of combining 2DGE with SW detection and on-blot digestion, we first used a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-CAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) fusion protein previously constructed in our laboratory 9 to model our first application of this potential proteomics approach. The method allowed rapid separation and characterization of GFP-C/EBP from a crude bacterial extracts without any other fractionation. We then used the method to characterize C/EBP from cultured HEK293 cell nuclear extract. The results show the method is feasible and leads to rapid characterization.

2.0 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Materials

Dithiothreitol (DTT), iodoacetamide (IDA), polyvinylpyrrolidone 40 (PVP40), zwittergent 3–16, octyl β-D-glucopyranoside (OGP), acetonitrile (ACN), trypsin (sequencing grade), 2-mercaptoethanol and Tris were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Nitrocellulose (NC), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), and other gel electrophoresis reagents were from BioRad Laboratories (CA, USA). C/EBP beta antibody (Δ198) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (CA, USA).

2.2 Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

The self-complementaty C/EBP oligonucleotide (5′-GCTGCAGATTGCGCAATCTGCAGC-3′, EP24) was annealed and 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P] ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Bacterial crude extract (1 μg) was mixed with labeled EP24 (1.6 nM final concentration) in a total volume of 25 μl 1 incubation buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT). After incubation at room temperature for 30 min, the complex was separated on a pre-electrophoresed 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.25X TBE buffer and detected by autoradiography. In competition assays, 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled duplex EP24, AP-1 (5′-CGC TTG ATG ACT CAG CCG GAA-3′ annealed with its complementary strand) was also added.

2.3 Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DGE)

Isoelectric focusing (IEF) was performed with ReadyStrip IPG strips (pH 3–10, linear, 7 cm) using PROTEAN IEF cell (BioRad) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Bacterial (BL21) crude extract, pure GFP-C/EBP which was purified by Ni2+–NTA-agarose chromatography from BL21 crude extract 9, or HEK293 nuclear extract (30–100 μg) was mixed in 125 μl rehydration buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2% CHAPS, 65 mM DTT, 8% Ampholytes, 1% Zwittergent 3–10, 0.01% bromophenol blue) and rehydrate at 50 V for 16 hours. IEF was at 40, 000 v.hr and 20 °C. Then, the strips were equilibrated in equilibration buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 6 M urea, 2% SDS, 30% glycerol, 0.0001% bromophenol blue) containing 2% DTT at room temperature for 15 min and then in equilibration buffer containing 2.5% iodoacetamide for 15 min. The strips were transferred to a 12% SDS-PAGE gel for second dimensional electrophoresis using the PROTEAN II xi 2-D (BioRad) cell. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with silver nitrate or transferred to NC or PVDF membrane for western blotting (WB) or Southwestern blotting (SW) analysis.

2.4 Southwestern blotting (SW)

A SW was performed as described 10 with minor modifications. Briefly, protein sample was separated by SDS-PAGE or 2DGE, and then transferred to NC or Sequi-blot PVDF membrane (0.2 μm) at 110 V for 1.5 hr in the cold room. The blotted proteins were denatured and renatured by immersing the blot in 6M guanidine HCl, which was then serially diluted to 3M, 1.5M, 0.75M, 0.375M, 0.188M, 0.094M using 1 binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100), with incubation at 4 °C for 10 min each time. The blot was blocked at room temperature for one hour in 1 binding buffer containing 5% non-fat milk, or in 0.5% PVP40 or 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16 in 1 binding buffer for 30 min or 5 min, respectively. When we compared the renaturation efficiency, 4M urea in 1 binding buffer was added to blot and incubated at room temperature for one hour instead of serially diluting 6M guanidine HCl to 0.094M using 1 binding buffer as described above. Subsequently, the membrane was probed overnight with [γ-32P] radiolabeled EP24 (1.5 nM, 106 cpm/ml) at 4 °C in 1 binding buffer containing 0.25% BSA, 10 μg/ml poly dI:dC. The washed membrane was air-dried and exposed for autoradiography or cut and quantified using a scintillation counter for Cerenkov radiation (LS 6500, Beckman Coulter, USA). In addition, different stripping buffers were tested for 10 minutes to remove the radiolabeled oligonucleotide from the blots, which includes SDS stripping buffer (62.5mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 100mM β-mercaptoethanol) at 50 °C, 2M sodium chloride, 3M potassium thiocyanate, 0.1M glycine, pH 2.0 and 6M guanidine HCl at room temperature, or TE buffer (10mM Tris, 1mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 95 °C.

2.5 Western blot (WB)

Gels were electroblotted onto 0.2 μm pore nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes as already described. The dilution for C/EBP antibody was 1:500. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using 1:10,000 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody-HRP conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, California, USA) and detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) using procedures previously described 11. In some experiments, SW and WB were done on the same blot. To do this, SW analysis was first performed without autoradiography, and then the same blot was probed with C/EBP antibody for WB. After the ECL signal of WB blot was developed, the ECL signal was allowed to decay completely overnight, then the same blot was further analyzed by autoradiography for the SW signal.

2.6 On-blot digestion for ESI-MS analysis

The protein bands or spots were excised from 1D or 2D-SW blots, cut into 1 mm X 1 mm pieces, stripped at 50°C with SDS stripping buffer for 10 min, and then the membrane was washed ten times with 500 μl H2O for 1 min. For 1D, the proteins on the blot were reduced with 10 mM DTT at 56 °C for one hour, and then alkylated by 55 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature in the dark for one hour. After washing with 500 μl 25 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.0) five times for 1 min, the blot was blocked with 10 μl of 1% Zwittergent 3–16, 1% PVP40 or 1% OGP in 25 mM NH4HCO3 (pH 8.0) at room temperature for 30 min and heated at 95°C for 5 min. Then acetonitrile (ACN), 10 μl of 40 μg/ml trypsin and an appropriate amount of 25 mM NH4HCO3 was added to a final volume of 40 μl, and digested overnight at 37 °C. The digestion solution was sonicated for 5 min and collected, and the peptides on the membrane were further extracted with 30 μl of 5% TFA/50% ACN at room temperature for one hour, and then 30 μl of 0.5% TFA/50% ACN at room temperature for another hour. The combined solution (100 μl) was vaccum dried and dissolved into 30 μl of 0.1% TFA, desalted by C18 ZipTip as per the manufacture’s protocol and the peptides were eluted with 20 μl 0.1%TFA/50% ACN (4 μl X5). Ten μl of eluate was diluted to 50 μl with 0.1% TFA/50% methanol containing 70 ng of Angiotensin II as an internal standard.

2.7 Infusion Nanospray-ESI-MS analysis

When optimizing on-membrane digestion, the eluate containing the internal standard was introduced into a Finnigan LCQDECA (ThermoQuest MS) equipped with a nanospray ionization interface. The ESI-MS was operated under the following conditions: NSI spray voltage, 2.0 kV (positive-ion mode); spray current: 0.29 μA; capillary temperature, 150°C. Sample (50 μl) was infused into the nanospray ion source with a 50 μl syringe pump at a flow rate of 0.25 μl/min. The spectra were accumulated for 5 min at mass range of 200–800 and 800–2000 Da individually. The precusor ion was further identified by data dependent MS/MS analysis using collision induced dissociation at 35% relative collision energy. The isolation width for the parent ion was adjusted manually (0.5–1% of the parent mass).

2.8 HPLC-nanospray-ESI-MS/MS analysis

After optimizing the on-blot digestion, the proteins binding EP24 were excised from 2DGE-SW membrane, digested on blot, and identified by HPLC-nanospray-ESI-MS/MS. After the peptides were desalted by C18 ZipTip, the eluate was lyophilized, resuspended in 10 μl of 0.1% TFA, and analyzed by capillary HPLC-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) using a Thermo Finnigan linear ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ) equipped with a nano-ESI source. On-line HPLC separation of the digests was accomplished with an Eksigent HPLC micro HPLC. The column was a PicoFrit™ (New Objective; 75 μm i.d.) packed to 10 cm with C18 adsorbent (Vydac 218MS, 5 μm, 300 Å). Mobile phase A was 0.5% acetic acid (HAc)/0.005% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and mobile phase B was 90% acetonitrile/0.5% HAc/0.005% TFA. The gradient was from 2 to 42% B in 30 min. The flow rate was 0.4 μl/min. MS conditions were a 2.9 kV ESI voltage, an isolation window for MS/MS of 3; 35% relative collision energy, with a scan strategy of a survey scan followed by acquisition of data dependent collision-induced dissociation (CID) spectra of the seven most intense ions in the survey scan above a set threshold.

2.9 Database search

The raw file of LC-MS/MS was searched against Swiss-Prot database 49.0 (268,833 sequences, 123,649,849 residues) or a local database using Mascot (version 2.1.0) software. The exact sequence of fusion protein GFP-C/EBP and C/EBP family members, including α, β,γ,δ, ε, and ζ, were added to the local database. The searching parameters are as followings: trypsin as enzyme, two possible missed cleavages, monoisotopic mass values; peptide tolerance, 1.0 Da; MS/MS tolerance, 0.8 Da; instrument, ESI-TRAP; oxidized methionine and cysteine carbamidomethylation as variable modification, For MS-MS sequence information, each raw file was also opened with Xcalibur software (version 2.0.5) and manually sequenced. Neutral mass of the parent and sequence information were used to identify proteins in the Swiss-Prot fused with in-house database using Mascot software (2.1.0). Results were scored using the probability-based Mowse score. The score threshold to achieve p < 0.05 is set by the Mascot algorithm and is based on the size of the database used in the search. Protein scores were derived from ion scores as a non-probabilistic basis and protein scores as the sum of a series of peptide scores. We accepted the protein identifications when Mascot scores were above the statistically significant threshold (p < 0.05) and the proteins with two unique peptides matched were considered as high confidence.

3.0 RESULTS

To test the feasibility of two-dimensional Southwestern blotting for transcription factor identification, the fusion protein GFP-C/EBP was firstly used as a model. Supplementary Figure 1A shows the protein sequence of the fusion protein. Supplementary Figure 1B shows the specific complex formed by GFP-C/EBP with EP24 oligonucleotide. Supplementary Figure 1C shows the GFP-C/EBP protein present in the bacterial crude extract and the highly purified GFP-C/EBP, containing a (His)6 N-terminal sequence, after Ni2+-NTA-agarose chromatography 9. Supplementary Figure 1D shows the results when one-dimensional gel blots are used for Southwestern blot (SW) with EP24 and western blot (WB) with a C/EBP antibody, which reacts with C/EBP α, β, δ, and ε isoforms. The lowest GFP-C/EBP amount (31.3 ng), easily detected by SW is equal to 0.7 pmol. Thus, SW has the needed sensitivity for our purpose and is more sensitive than WB with this commercial antibody.

In order to systematically optimize the conditions for SW analysis, we used bacterial crude extract containing GFP-C/EBP as a model. A large, single-well SDS-PAGE gel was used to separate bacterial crude extract. After SW analysis, the EP24-binding band (GFP-C/EBP) was located using autoradiography and the blot cut into identical strips. Using the scintillation counter, the SW signal can be quantified. First, the SW signal of GFP-C/EBP from bacteria crude extract on NC and PVDF membrane was compared. Panel 1 of Table 1 shows that PVDF membrane has about 2.5–3-fold greater signal than NC during SW analysis. The effect of different blocking agents, including 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16, 0.5% PVP40 and 5% non-fat milk, was also determined, and shows that 0.5% PVP40 is a good choice for PVDF membrane blocking during SW analysis. Furthermore, the renaturing buffer was compared in panel 2 of Table 1. Although urea renaturation on PVDF blot gave more SW signal than guanidine HCl, more protein was removed from the blot when using urea as determined by Coomassie blue staining and densitometry. In addition, the stripping condition was investigated as shown in panel 3, SDS stripping buffer can efficiently remove radiolabeled oligonucleotide from PVDF membrane as compared with the other buffers, which were less effective at removing the radiation. So the optimal SW conditions determined are: PVDF membrane, 0.5% PVP40 for blocking, guanidine HCl for renaturation and SDS stripping buffer to remove radiation from the blot prior to proteomic characterization.

Table 1.

Optimization of Southwestern blot (SW) analysis

| 1. SW comparison between NC and PVDF using different blocking buffers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blot | Zwittergent | PVP40 | milk |

| NC | 922±221 | 879±78 | 681±117 |

| PVDF | 2335±111 | 2861±72 | 1929±318 |

| 2. SW comparison between urea and guanidine HCl for renaturing | ||

|---|---|---|

| Urea | Guanidine HCl | |

| Cpm | 849±27 | 568±35 |

| Protein retained on membrane | 43±1% | 60±7% |

| 3. Stripping comparison for PVDF membrane | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stripping buffer | Cpm remaining | |

| SDS stripping buffer, 50 °C | 93±18 | |

| 2M NaCl | 2269±77 | |

| 3M KSCN, pH 7.5 | 1119±325 | |

| 0.1M glycine, pH 2.0 | 2189±58 | |

| 6M guanidine HCl | 1247±308 | |

| TE, 95 °C | 2411±57 | |

| Control (unstripped) | 2419±107 | |

Average and standard deviation are calculated from three independent experiments.

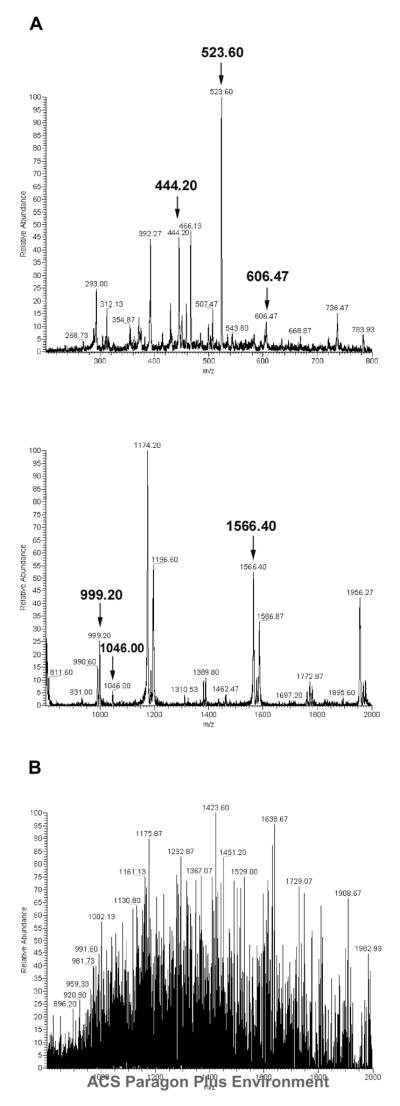

In this study, the on-blot digestion conditions were also optimized, using purified GFP-C/EBP as a model. By using the optimal SW conditions described above, the GFP-C/EBP band on the SW blot was excised, digested with trypsin and analyzed by nano-ESI-MS analysis. Figure 1A shows the typical infusion MS spectra using 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16 in the digestion solution. Supplementary Figure 2 shows the MS/MS spectra of four parent peptides with m/z at about 444.2 (2+), 606.6 (2+), 999.6 (1+) and 1566.6 (1+), confirming that these four peptides, indicated by arrows in Figure 2A, were fragments of GFP-C/EBP. Fig 1B shows what happens when PVP40 is used for blocking immediately prior to on-blot digestion; the multiple peaks presumably result from fragmentation of this complex polymer. This makes PVP40 undesirable during digestion.

Figure 1.

Optimization of on-blot digestion after Southwestern blotting analysis. 20 μg of purified GFP-C/EBP was applied to a large single well and separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose (NC) and PVDF membrane for SW analysis. The proteins on the blots were denatured and renatured by guanidine HCl and blocked with 0.5% PVP40. After autoradiography, the blot was cut into ten equal strips for on-blot digestion. The blot was stripped by SDS stripping buffer. After reduction and alkylation, the strip was digested in the presence of 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16 and 30% ACN at 37 °C overnight. Desalted by C18 ZipTip, the eluted peptides in 0.1% TFA+50%ACN containing angiotensin II (1046 Da, 70 ng) used as an internal control were analyzed by infusion ESI-MS. The precursor peptides were further identified by ESI-MS/MS analysis. A, The infusion ESI-MS result using 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16 in on-blot digestion conditions is shown with mass range (200–800Da, upper panel) and (800–2000Da, lower) separately. The precursor peptides for MS/MS identification (m/z at 444, 606, 999, and 1566), and the Angiotensin II internal control (1046, or 523, 2+) are indicated with arrows. B, shows the MS spectra (800–2000Da) of the same procedure using PVP40 in the place of Zwittergent.

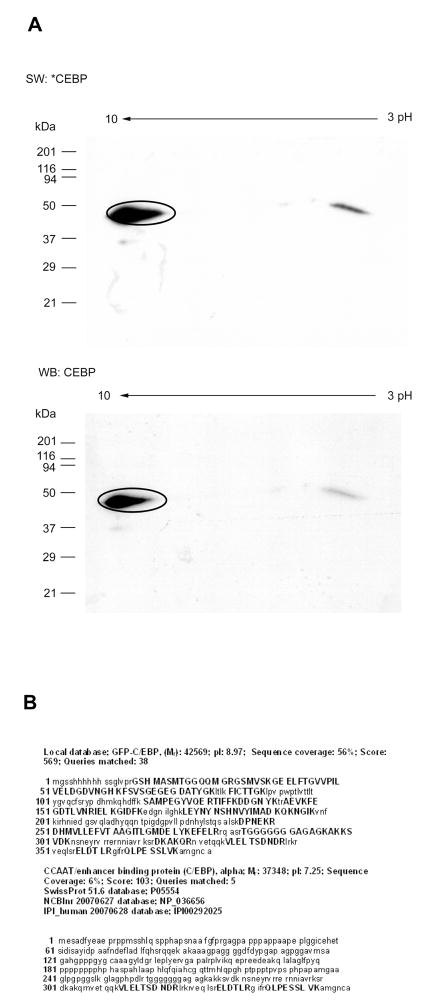

Figure 2. 2D Southwestern blotting analysis of purified GFP-C/EBP.

A, Comparison of 2D-SW and 2D-WB analysis of GFP-C/EBP fusion protein. Purified GFP-C/EBP (1 μg) was separated by 2DE and transferred to PVDF membrane for SW and WB analysis. The molecular mass of standard is shown on the left, pH on the top of the 2DE gel. The upper part shows the 2D-SW result, a spot with pI 9.0, M.W 46 kDa indicating the position of GFP-C/EBP, is also detected at same position in 2D-WB analysis shown in the lower panel. B, MS analysis of a spot on 2D-SW blot. The encircled spot on the 2D-SW blot (Panel A) corresponding to GFP-C/EBP was identified by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis and database search. The protein sequence coverage is shown with bold, capital letters; the Local database search indicates the sequence coverage reached 56%, while the SwissProt, NCBInr and human IPI database searching shows sequence coverage at 6% with mammalian C/EBP α.

In the experiment, Angiotensin II was used as an internal control with m/z at 523.6 (2+) and 1046.2 (1+). The relative intensity of the GFP-C/EBP peptides was divided by the angiotensin signal to normalize all the data. These normalized ratios are compared in Table 2. First, the peptide yields from trypsin digestion on-blot were compared between NC and PVDF membrane. After SW analysis, the membranes with/without stripping were on-blot digested in the presence of 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16 (in the absence of PVP-40), and the yield including 606.6, 999.6 and 1566.6 peptides on PVDF membrane was divided by the results from NC. As shown in panel 1, PVDF shows 5–10 fold higher peptide yield than on NC when membranes were previously stripped of radioactive DNA. Without stripping, the ratio is diminished to about two, suggesting that lower losses from PVDF blot during stripping contributes to its performance. This is confirmed in panel 2. Stripping has little effect on the peptide yield of on-PVDF-blot digestion. On-NC-blots, stripping remove much more of the bound proteins from the blot.

Table 2.

Optimization of on-membrane digestion

| 1. MS comparison between PVDF and NC membrane | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strip | Blot | 606.6 | 999.6 | 1566.6 |

| + | PVDF/NC | 4.9 | 12.3 | 11.0 |

| − | PVDF/NC | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.4 |

| 2. MS comparison between stripping and no stripping | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blot | Strip | 606.6 | 999.6 | 1566.6 |

| PVDF | −/+ | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| NC | −/+ | 2.3 | 6.2 | 7.5 |

| 3. MS comparison using different agentsa in digestion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agents | 444.2 | 606.6 | 999.6 | 1566.6 |

| Zwittergent | 0.4 | 27.2 | 12.5 | 26.8 |

| OGP | 3.3 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| PVP40 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 8.7 |

| 4. MS comparison using different concentration of ACN in the presence of Zwittergentb | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ACN | 606.8 | 999.6 | 1566.6 |

| 10% | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| 20% | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.8 |

| 30% | 1.5 | 2.9 | 4.4 |

| 50% | 0.8 | 1.4 | 7.1 |

| 5. LC-MS/MS comparison using different membranes and blocking buffers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blot | Blocking buffer | Sequence coverage | Score |

| NC | PVP40 | 51% | 755 |

| PVDF | milk | 24% | 130 |

| PVDF | Zwittergent | 20% | 327 |

| PVDF | PVP40 | 72% | 711 |

Results of detergents divided by that of no detergent.

Results with ACN were divided by results with absence.

Digests also included 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16.

The data are representative of three independent analyses.

It has been reported that detergent can help extraction and solubilization of peptides generated from proteolytic digestion and that acetonitrile (ACN) improves digestion efficiency. As shown above, the PVDF membrane gave rise to higher peptide recovery than NC. We compared the efficiency using different detergents and different concentration of ACN during on-PVDF-blot digestion, each time comparing the ratio to trypsin digestion with no additions. Panel 3 indicates that Zwittergent 3–16 provides 12–27 fold higher peptide recovery of 606.6, 999.6 and 1566.6 peptides compared with no detergent, and 30% ACN is found to increase the three peptide yields by 1.5–4.4 fold in the presence of Zwittergent 3–16. OGP helps extraction of peptides 444.2 and 606.6 by 2–3 fold compared with no detergent. As PVP40 is a polymer, it complicates the spectra as have been seen in Figure 1B. So PVP40 is not recommended to be used during or immediately prior to proteolytic digestion and also did not increase peptide yield as well as Zwittergent.

In SW analysis of bacteria crude extract containing GFP-C/EBP, three different blocking buffers as mentioned in Table 1, i.e. 5% non-fat milk, 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16 and 0.5% PVP40, were chosen to block PVDF membrane after it was denatured and renatured, and the on-PVDF digested peptides were analyzed by HPLC-nano-ESI-MS/MS. By comparing sequence coverage after database searching, we were able to refine blotting and blocking methods as shown in Panel 5. When either 5% non-fat milk or the detergent Zwittergent 3–16 were used, proteomic identification and sequence coverage were much less definitive than when PVP-40 was used, making PVP40 the preferred SW blocking method, the same result as SW optimization shown in Table 1 Panel 1. HPLC-MS/MS identification indicates that 0.5% PVP40 blocking buffer gave rise to 72% sequence coverage of GFP-C/EBP, while the sequence coverage of 5% non-fat milk and 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16 is 24% and 20%, respectively. In addition, GFP-C/EBP derived from bacteria crude extract has higher sequence coverage (72%) on PVDF than on NC membrane (51%).

Thus, for the SW analysis, we conclude that PVDF should be used with PVP40 blocking, guanidine HCl renaturation, stripping should be using the SDS protocol, and on-blot trypsin digestion should be performed in the presence of 0.5% Zwittergent 3–16 and 30% ACN. These conditions are used for all subsequent experiments.

Figure 2 shows a two-dimensional Southwestern and western blot of the purified GFP-C/EBP. The major component has an isoelectric point and mass corresponding closely to the calculated values. A minor component has a much more acidic isoelectric pH. The major spot was cut from the blot, digested on the PVDF blot with trypsin, and subjected to LC-MS/MS identification. The local database search result shows that GFP-C/EBP was identified with a very high score and 56% sequence coverage, not a surprising result for a highly purified protein. The sequence coverage covers all three regions including His tag, E-GFP and C/EBP alpha. As the 99 amino acid of GFP-C/EBP C-terminus came from rat C/EBP alpha, three peptides came from C/EBP alpha are matched after searching the mammalian databases containing SwissProt, NCBInr and IPI, as shown in Figure 2B, confirming the correct sequence of GFP-C/EBP. The fragment ions of the precursor peptide VLELTSDNDR (337–346 aa. of GFP-C/EBP) with m/z 581.10 (2+) is shown in supplementary Fig 3A.

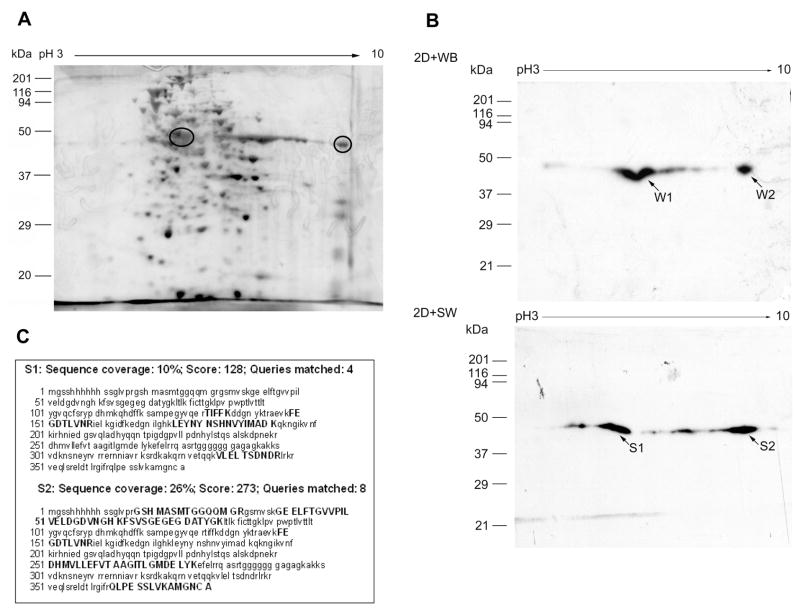

To further test the method, a two-dimensional separation of the bacterial crude extract, rather than the purified protein was used. The silver stained 2D gel result is shown in Fig. 3A and contains a very large number of proteins. Fig. 3B shows the corresponding SW proteins probed with the radiolabeled EP24 oligonucleotide. There are two major (labeled S1 and S2) EP24 binding spots. The two major spots were cut from the PVDF blot, trypsin digested, and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. The S1 spot gave only 10% sequence coverage; three unique peptides from E-GFP and one peptide from C/EBP alpha sequence. The S2 spot, with an isoelectric pH at about 9.0 corresponding to that calculated for this protein, is clearly intact GFP-C/EBP with 26% sequence coverage representing all sequence regions of the fusion protein. Interestingly, 2D-WB analysis indicates that both W1 and W2 spots interact with C/EBP antibody at the same position of 2D-SW marked as S1 and S2, implying some modification of GFP-C/EBP in bacteria crude extract. In addition, the fragment ions of two precursor peptides, TIFFK (aa. 132–136) from spot S1 with m/z at 655.22 (1+) and FSVSGEGEGDATYGK (aa. 62–86) from spot S2 with m/z at 752.16 (2+), are shown in supplementary Figure 3B and 3C, respectively.

Figure 3. 2D-SW analysis of bacterial crude extract containing GFP-C/EBP.

The same amount of crude bacterial GFP-C/EBP extract (30 μg/each) was separated by 2DE. A, One 2DE gel was stained with silver nitrate. B, Two gels were transferred to PVDF membrane for SW and WB analysis. During SW analysis, 0.5% PVP40 was used in the blocking buffer. The molecular masses of standards are shown on the left. The pH units of IPG strips are shown at the top. The position of GFP-C/EBP corresponding to SW spots is circled in panel A. The comparison of 2D-SW and 2D-WB result is shown in panel B. The protein spots which bind C/EBP antibody are indicated as “W1” and “W2”, and the protein spots which bind radiolabeled EP24 are indicated as “S1” and “S2”. C, MS analysis of 2D-SW protein spots of crude bacterial GFP-C/EBP extract. “S1” and “S2” protein spots on 2D-SW blot were digested by trypsin and analyzed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS.

To further challenge this new technique, Fig. 4A shows the result of one dimensional SW obtained from HEK293 nuclear extract containing native C/EBP. There are two closely spaced protein bands, close to 37 kDa, binding radiolabeled EP24 or C/EBP antibody. Fig 4C shows the result of two dimensional SW and WB of HEK293 nuclear extract, demonstrating the presence of C/EBP and the coincidence of 2D-SW and WB. After aligning the 2D-SW spots with the silver stained 2DE gel of nuclear extract (Fig 4B), it is apparent that C/EBP proteins are of very low abundant in HEK293 nuclear extract, hardly visible by silver staining. Furthermore, the spots, labeled “a” and “b” on the two dimensional SW, were cut, digested and identified. As shown in Fig 4D, the spot “a” is identified as human CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta (C/EBP beta) with theoretical pI of 8.55 and molecular mass of 36 kDa, consistent with the position on two dimensional SW and WB. There are two unique peptides matched with human C/EBP beta after searching SwissProt fused with in-house database, which are: APPTACYAGAAPAPSQVKSK (243–262 aa., expect value is 0.0035) with m/z at 639.18(3+) shown in supplementary Fig 3D and AKMRNLETQHK (292–302 aa., expect value is 0.012) with m/z at 686.15 (2+) shown in Fig 4D, and the sequence coverage of C/EBP beta is 9%.

Figure 4. 2D-SW analysis of HEK293 nuclear extract.

A, Comparison of 1D-SW and WB analysis. HEK293 nuclear extract (20 μg/each) was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to a PVDF membrane for SW and WB analysis. B, HEK293 nuclear extract was separated by 2DE. One 2D gel (50 μg) was stained with silver nitrate in panel B, C, and two gels (100 μg) were transferred to PVDF membrane for WB (upper panel) and SW (lower) analysis in panel C. The two protein spots on the blots that reacted with the C/EBP antibody and radiolabeled EP24 are indicated as “a” and “b”. The 2D-SW spots were analyzed by on-blot digestion and HPLC-nano-ESI-MS/MS analysis, spot “a” was successfully identified as human C/EBP beta, as shown in panel D. D, MS/MS analysis of 2D-SW protein spot “a”. MS/MS results shows that there are two unique peptides from spot “a” matched with human C/EBP beta (NP-005185) with 9% sequence coverage after searching local and SwissProt database. The spectra represent the doubly charged peptide AKMRNLETQHK at m/z 686.15 (2+). The matched b- and y- ions, derived from the peptide are indicated with arrows. The amino acid sequence of the parent peptide is shown on the top of the spectrum.

DISCUSSION

SW has been widely used to determine the molecular weight of the DNA-binding proteins. Recently for example, a 40-kDa protein in regenerated rat liver was found to bind the −148–124 sequence in the c-jun promoter 10. A potential novel enhancer protein with molecular weight of 96-kDa, was found to bind a specific sequence (−133–122) on human MCT-1 oncogene promoter 12. SW analysis also determined that two proteins with molecular weight at 48-kDa and 70-kDa were capable of binding a putative insulin-responsive element in Rat angiotensinogen promoter 13. Sometimes the molecular weight of DNA-binding protein can help identity of the responsible protein(s) by searching transcription factors databases such as TransFac. and using EMSA supershift and a specific antibody when an antibody is available. Often though, like the four DNA binding proteins mentioned above, the identity is still not known primarily because of the very low abundance of DNA binding proteins and lack of specific antibodies. In this situation and others, 2D-SW and proteomic methods can make identification and characterization possible.

Southwestern blots of two-dimensional gel separations have been used once before for this purpose, but this used alignment of a 2D gel with a SW blot to identify gel spots for further analysis by in-gel digestion 14. Here, we have developed 2D-SW methods that allow nuclear extract to be resolved by two-dimensional electrophoresis and used the SW technique to detect where transcription factors of interest are positioned on the blot and used the blot itself for further analysis avoiding any errors in alignment. In our study, we have successfully characterized a transcription factor model from bacterial crude and HEK293 nuclear extract. These techniques are an improvement over existing methods. Furthermore, it requires only that the DNA response element bound by the transcription factor be known, which is essentially always the case.

In this study, we systematically optimized the SW conditions by a series of experiments. The best SW conditions determined are: PVDF membrane, 0.5% PVP40 to block the blot, guanidine HCl to renature proteins on the blot and SDS stripping buffer to strip radiation. When the scintillation counting was calibrated for Cerenkov efficiency, we determined that 25% of the protein (GFP-C/EBP) on the renatured blot bound with EP24, which is quite high efficiency for a multi-step procedure. Actually, when we electroblot for a longer time (2 hr), the transferring efficiency can be further increased (data not shown).

Blocking with 0.5% PVP40 for SW produce more SW signal, better subsequent peptide yield and sequence coverage. This agrees with previous results where Bunai et al 15 successfully analyzed 100–500 fmol standard proteins immobilized on PVDF membrane, which were blocked with 0.5% PVP40, washed and digested by trypsin in 80% ACN. But PVP40 during digestion results in a complex MS spectrum (Fig 1B) due to PVP40 polymer fragmentation. So PVP40 can be used to block membrane during SW analysis, but it should be completely washed away after blocking.

In the present study, Zwittergent 3–16 was found to be useful for extracting and solubilizing peptides generated from on-blot digestion as described before 16. Zwittergent 3–16, which consists of an ionic sulfonate head, a quarternary amine and a hydrophobic un-branched 16C tail, providing both strong hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity, has been used to block nitrocellulose membrane during on-blot proteolytic digestion 17. In our study, Zwittergent shows higher recovery for most GFP-C/EBP peptides increasing peptide recovery by as much as 27 fold. However, high concentrations of Zwittergent are known to interfere with peptide mass fingerprinting. To remove Zwittergent, we used reverse-phase HPLC separation before ESI-MS/MS analysis 16, 18.

The organic solvent ACN helps extract peptides from PVDF membrane in high concentration up to 80% and increases peptide yield 15, 19, 20. It has been reported that 70% ACN and 30% methanol in MALDI matrix solution greatly improve the on-NC digestion 21, 22. In this study, we found that 30% CAN combined with 0.5% zwittergent 3–16 was optimal for most peptides studied (panel 4, Table 2).

We also compared the peptide yield with or without SW stripping protocol before on-blot digestion. The result shows that stripping has no large effect on a PVDF blot, but it significantly lessens peptides from NC blot, indicating stripping step may remove proteins from NC to some degree. As anticipated, PVDF membrane shows much higher protein binding ability and peptide recovery compared with nitrocellulose membrane 23.

Compared with 2D-WB, 2D-SW provides similar or greater sensitivity when it is combined with on-blot digestion and MS analysis. Klarskov’s lab has detected 1pmol of standard proteins after WB on PVDF membrane and on-blot digestion 24. Both methods share the procedures of 2DE separation, electrotransfer to PVDF or NC membrane, on-blot digestion and MS identification. Some procedures are different, for example, stripping buffer used for WB (0.1M glycine, pH 2.0) doesn’t work for SW stripping. And 2D-WB requires a specific antibody while 2D-SW blot is probed with specific oligonucleotide and can be applied even when the DNA binding protein is still unidentified and no antibody is available.

Recent data from our laboratory used EMSA and Scatchard analysis to determine that the HEK293 nuclear extract (100 Eg) loaded on the SW blot in Fig 4 contains less than 2 picomol of C/EBP 25. Thus, analysis here after so many steps probably represents sub-pmol characterization of a transcription factor. To our knowledge, no identification of transcription factor from cell nuclear extract has ever been reported without extensive protein purification. In our study, we clearly identified C/EBP-β from HEK293 nuclear extract. Recently, the purification of transcription factors has been improved by using the oligonucleotide trapping method in which an oligonucleotide is constructed with a specific duplex DNA response element that is bound by a transcription factor and a single-stranded DNA tail used for recovery. The DNA is added at nanomolar concentration to nuclear extract where it forms a complex with the transcription factor(s) specific for that element. The complex is then recovered by annealing the single-stranded tail to a complementary single-stranded DNA-column. This method has been used for the successful purification and characterization of the Xenopus B3 transcription factor, the CAAT enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), MafA 26, 27 and recently, a transcription factor complex binding to a novel element in the c-jun promoter 28. Although sometimes a homogenous protein can be obtained in single-step purification, often this is not the case and further fractionation is required. So we next plan to couple this new 2D-SW with on-blot digestion to oligonucleotide trapping to learn if this may provide a facile way to characterize any novel transcription factor.

Conclusions

The 2DE-SW with on-blot trypsin digestion provides a way to characterize a transcription factor directly from crude nuclear extracts without prior purification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Maria Macias for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant GM043609. We also thank Dr. William Haskins at the RCMI Proteomics Facility of the University Texas at San Antonio for the LC-ESI-Mass Spectra for analysis and many helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information consists of two figures and one table. One figure gives the MS/MS results showing four peptides used to identify GFP-C/EBP in the experiments. The second figure gives MS/MS spectra of precursor peptides from both the bacterial GFP-C/EBP and the HEK293 C/EBP identified in 2DE Southwestern blot experiments. The table shows all other nucleotide binding proteins found in our analysis of HEK 293 nuclear extract.

References

- 1.Graves PR, Haystead TA. Molecular biologist’s guide to proteomics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66(1):39–63. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.1.39-63.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffin TJ, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R. Advances in proteome analysis by mass spectrometry. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2001;12(6):607–12. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(01)00268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Farrell PH. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wittmann-Liebold B, Graack HR, Pohl T. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis as tool for proteomics studies in combination with protein identification by mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2006;6(17):4688–703. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen B, Steinberg J, Laemmli UK, Weintraub H. The detection of DNA-binding proteins by protein blotting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8(1):1–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siu FK, Lee LT, Chow BK. Southwestern blotting in investigating transcriptional regulation. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(1):51–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Labbe S, Stewart G, LaRochelle O, Poirier GG, Seguin C. Identification of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins by southwestern blotting. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;148:255–64. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-208-2:255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang X, Bai J, Liu YH, Lubman DM. Characterization of SDS--PAGE-separated proteins by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1996;68(6):1012–8. doi: 10.1021/ac950685z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarrett HW, Taylor WL. Transcription factor-green fluorescent protein chimeric fusion proteins and their use in studies of DNA affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 1998;803:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)01257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohri S, Sharma D, Dixit A. Interaction of an approximately 40 kDa protein from regenerating rat liver with the −148 to −124 region of c-jun complexed with RLjunRP coincides with enhanced c-jun expression in proliferating rat liver. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271(23–24):4892–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oak SA, Jarrett HW. Skeletal Muscle Signaling Pathway Through the Dystrophin glycoprotein Complex and Rac1. Biochemistry. 2003;278(41):39287–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi B, Levenson V, Gartenhaus RB. Identification and characterization of a novel enhancer for the human MCT-1 oncogene promoter. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90(1):68–79. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, Zhang SL, Pang L, Filep JG, Tang SS, Ingelfinger JR, Chan JS. Characterization of a putative insulin-responsive element and its binding protein(s) in rat angiotensinogen gene promoter: regulation by glucose and insulin. Endocrinology. 2001;142(6):2577–85. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei CC, Guo DF, Zhang SL, Ingelfinger JR, Chan JS. Heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F modulates angiotensinogen gene expression in rat kidney proximal tubular cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(3):616–28. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bunai K, Nozaki M, Hamano M, Ogane S, Inoue T, Nemoto T, Nakanishi H, Yamane K. Proteomic analysis of acrylamide gel separated proteins immobilized on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes following proteolytic digestion in the presence of 80% acetonitrile. Proteomics. 2003;3(9):1738–49. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pham VC, Henzel WJ, Lill JR. Rapid on-membrane proteolytic cleavage for Edman sequencing and mass spectrometric identification of proteins. Electrophoresis. 2005;26(22):4243–51. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lui M, Tempst P, Erdjument-Bromage H. Methodical analysis of protein-nitrocellulose interactions to design a refined digestion protocol. Anal Biochem. 1996;241(2):156–66. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pham V, Henzel WJ, Arnott D, Hymowitz S, Sandoval WN, Truong BT, Lowman H, Lill JR. De novo proteomic sequencing of a monoclonal antibody raised against OX40 ligand. Anal Biochem. 2006;352(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obama T, Kato R, Masuda Y, Takahashi K, Aiuchi T, Itabe H. Analysis of modified apolipoprotein B-100 structures formed in oxidized low-density lipoprotein using LC-MS/MS. Proteomics. 2007;7(13):2132–41. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strader MB, Tabb DL, Hervey WJ, Pan C, Hurst GB. Efficient and specific trypsin digestion of microgram to nanogram quantities of proteins in organic-aqueous solvent systems. Anal Chem. 2006;78(1):125–34. doi: 10.1021/ac051348l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luque-Garcia JL, Zhou G, Sun TT, Neubert TA. Use of nitrocellulose membranes for protein characterization by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2006;78(14):5102–8. doi: 10.1021/ac060344t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luque-Garcia JL, Zhou G, Spellman DS, Sun TT, Neubert TA. Analysis of electroblotted proteins by mass spectrometry: protein identification after Western blotting. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7(2):308–14. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700415-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez J, Mische SM. Enzymatic digestion of proteins on PVDF membranes. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2001;Chapter 11(Unit 11 2) doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps1102s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Methogo RM, Dufresne-Martin G, Leclerc P, Leduc R, Klarskov K. Mass spectrometric peptide fingerprinting of proteins after Western blotting on polyvinylidene fluoride and enhanced chemiluminescence detection. J Proteome Res. 2005;4(6):2216–24. doi: 10.1021/pr050014+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panda M, Jiang D, Jarrett HW. Trapping of transcription factors with symmetrical DNA using thiol-disulfide exchange chemistry. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1202(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuoka T, Zhao L, Artner I, Jarrett H, Friedman D, Means A, Stein R. Members of the large Maf transcription family regulate insulin gene transcription in islet beta cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6049–6062. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6049-6062.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moxley RA, Jarrett HW. Oligonucleotide trapping method for transcription factor purification -systematic optimization using electrophoretic mobility shift assay. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1070:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang D, Zhou Y, Moxley RA, Jarrett HW. Purification and identification of positive regulators binding to a novel element in the c-Jun promoter. Biochemistry. 2008;47(35):9318–34. doi: 10.1021/bi800285q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.