Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that increased dopaminergic sensitivity induced by olfactory bulbectomy is mediated by dysregulation of endocannabinoid signaling. Bilateral olfactory bulbectomy induces behavioral and neurobiological symptomatology related to increased dopaminergic sensitivity. Rats underwent olfactory bulbectomy or sham operations and were assessed two weeks later in two tests of hyperdopaminergic responsivity: locomotor response to novelty and locomotor sensitization to amphetamine. Amphetamine (1 mg/kg i.p.) was administered to rats once daily for eight consecutive days to induce locomotor sensitization. URB597, an inhibitor of the anandamide hydrolyzing enzyme fatty-acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), was administered daily (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) to sham and olfactory bulbectomized (OBX) rats to investigate the impact of FAAH inhibition on locomotor sensitization to amphetamine. Pharmacological specificity was evaluated with the CB1 antagonist/inverse agonist rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p). OBX rats exhibited heightened locomotor activity in response to exposure to either a novel open field or to amphetamine administration relative to sham-operated rats. URB597 produced a CB1-mediated attenuation of amphetamine-induced locomotor sensitization in sham-operated rats. By contrast, URB597 failed to inhibit amphetamine sensitization in OBX rats. The present results demonstrate that enhanced endocannabinoid transmission attenuates development of amphetamine sensitization in intact animals but not in animals with OBX-induced dopaminergic dysfunction. Our data collectively suggest that the endocannabinoid system is compromised in olfactory bulbectomized rats.

Keywords: olfactory bulbectomy, endocannabinoid, amphetamine sensitization, FAAH, anandamide, dopamine

INTRODUCTION

Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are widely distributed throughout the brain of several mammalian species, including rodents and humans (Herkenham et al., 1991; Herkenham et al., 1990). The best characterized endogenous ligands for this receptor are anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) (Devane et al., 1992; Di Marzo et al., 1994; Stella et al., 1997). Endocannabinoids are synthesized and released on demand and then are rapidly deactivated by transport into cells followed by enzymatic hydrolysis (for review see Piomelli, 2005). Activation of presynaptic CB1 receptors inhibits neurotransmission in a retrograde manner (Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001; Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2001; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001). Endocannabinoids modulate both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission to control homeostasis throughout the central nervous system (Di Marzo and Petrosino, 2007).

The endocannabinoid system also modulates activity of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. CB1 receptors are located in the striatum (Herkenham et al., 1991; Hohmann and Herkenham, 2000; Mailleux and Vanderhaeghen, 1992), where they reside presynaptically on glutamatergic afferents as well as GABAergic interneurons (Monory et al., 2007). In the striatum, cannabinoid CB1 mRNA is localized to GABAergic medium spiny projection neurons as well as GABAergic interneurons (Herkenham et al., 1991; Hohmann and Herkenham, 2000; Mailleux and Vanderhaeghen, 1992). Postsynaptic endocannabinoid release is necessary for CB1-mediated long-term depression of glutamatergic transmission in the striatum (Gerdeman et al., 2002). Thus, endocannabinoids may act as retrograde messengers to suppress cortico-striatal glutamate release onto striatal medium spiny neurons. Direct and indirect dopamine agonists also increase striatal anandamide levels (Centonze et al., 2004; Giuffrida et al., 1999). These findings suggest functional interactions between the endocannabinoid, glutamatergic and dopaminergic signaling systems.

We hypothesized that hyperdopaminergic dysfunction observed following olfactory bulbectomy is associated with impaired endocannabinoid signaling. Bilateral olfactory bulbectomy in the rodent induces heightened locomotor responsivity to a novel open field (i.e. novelty) (Klein and Brown, 1969; van Riezen and Leonard, 1990) and a “presensitized” locomotor response to indirect dopaminergic agonists such as cocaine (Chambers et al., 2004) and amphetamine (Gaddy and Neill, 1976). In addition, olfactory bulbectomized rats exhibit faster acquisition of amphetamine self-administration relative to sham rats (Holmes et al., 2002). Olfactory bulbectomy induces sprouting of dopaminergic axons in the ventral striatum, in which basal dopamine release and dopamine receptor levels are increased at behaviorally relevant time points (Gilad and Reis, 1979; Holmes, 1999; Lingham and Gottesfeld, 1986; Masini et al., 2004). The olfactory bulbectomized (OBX) rat thus serves as a model of dopaminergic hyperfunction.

Anandamide and its related bioactive congeners, the N-acylethanolamines (NAEs), are likely to be synthesized presynaptically by the enzyme N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine-hydrolyzing phospoholipase D (NAPE-PLD). NAPE-PLD is confined to glutamatergic axon terminals, where the enzyme is found in association with intracellular calcium stores (Nyilas et al., 2008). Thus, the biosynthesis of anandamide may be related to the calcium-dependent state of glutamatergic axonal terminal. In the striatum, a portion of glutamatergic afferents are removed by olfactory bulbectomy (Kelly et al., 1997), suggesting that olfactory bulbectomy may also impair glutamate-dependent anandamide biosynthesis.

Anandamide is deactivated by the enzyme fatty-acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) (Cravatt et al., 1996, 2001; Devane et al., 1992). FAAH is localized to soma and dendrites of neurons that are postsynaptic to presynaptic CB1 receptors (Egertová et al., 2003). Unlike direct agonists of CB1 receptors, FAAH inhibitors do not produce unwanted psychoactive side-effects or profound motor impairment (Piomelli, 2005). The FAAH inhibitor URB597 produces CB1-mediated anxiolytic effects (Kathuria et al., 2003; Moise et al., 2008; Patel and Hillard, 2006) as well as antidepressant (Bortolato et al., 2007) and anti-impulsivity (Marco et al., 2007) effects. Thus, URB597 represents a useful tool for studying the impact of FAAH inhibition on dopamine-dependent behaviors.

We used the olfactory bulbectomy model to investigate the role of endocannabinoids in modulating behaviors influenced by dopaminergic dysfunction – the locomotor response to novelty and sensitization to amphetamine. First, the olfactory bulbectomy model was validated by assessing locomotor activity in response to exposure to a novel open field in both sham-operated and OBX rats. Next, locomotor sensitization to amphetamine was profiled in OBX and sham rats over eight consecutive days of amphetamine administration. The FAAH inhibitor URB597 was administered at a dose known to selectively increase the bioavailability of anandamide without altering levels of 2-arachidonoylglycerol in intact rats (Kathuria et al. 2003). We tested the hypothesis that FAAH inhibition would suppress amphetamine sensitization in sham-operated animals but not in animals in which a hyperdopaminergic state was induced by olfactory bulbectomy. The contribution of CB1 receptors to URB597-mediated actions was evaluated using the competitive CB1 antagonist/inverse agonist rimonabant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and Surgical Procedures

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (N = 60), Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) weighing approximately 250 – 300 g at surgery were used. All procedures were approved by the University of Georgia Animal Care and Use Committee. Rats were housed in groups of two to five in a humidity- and temperature-controlled animal housing facility. Lights in the colony room were on at 0600 and off at 1800. All behavioral testing was initiated during the light phase. Rats were randomly assigned to either sham or olfactory bulbectomy surgery. For olfactory bulbectomy surgery, rats (n = 18) were anesthetized with a combination of pentobarbital (65 mg/kg i.p.; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg i.p.; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, IA) or isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). Burr holes measuring 3 mm in diameter were bilaterally drilled approximately 5 mm anterior to bregma and 1 mm lateral to the midline. The dura mater was pierced and a curved plastic pipette tip was used to aspirate the olfactory bulbs. The resulting cavity was filled with Gelfoam (Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI). Rats receiving the sham surgery (n = 42) underwent the same procedure except that the olfactory bulbs were not aspirated. Confirmation of olfactory bulb lesion was determined by brain dissection at the end of the experiment. Lesions were considered complete if the bulbs were completely severed from the forebrain, the weight of the tissue dissected from the olfactory bulb cavity did not exceed 5 mg, and frontal lobes were not bilaterally damaged. Histological verifications were performed by an experimenter blinded to the surgical condition.

Pharmacological Manipulations

URB597 was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Rimonabant was a gift from NIDA. D-amphetamine sulfate was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). URB597 and rimonabant were dissolved in a 1:1:8 ratio of 100% ethanol:emulphor:saline. D-amphetamine sulfate (1 mg/kg) was dissolved in 0.9% saline. Drugs were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) in a volume of 1 ml/kg body weight. The FAAH inhibitor URB597 was administered at a dose (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) which selectively increases anandamide accumulation in intact rats, without altering levels of 2-AG (Kathuria et al., 2003). Rimonabant was administered at a dose (1 mg/kg i.p.) that blocks pharmacological effects of URB597, but does not exert locomotor or anxiogenic effects when administered alone (Jarbe et al., 2006; Moise et al., 2008; Patel and Hillard, 2006). Animals were randomly assigned to drug conditions that included ethanol: emulphor: saline vehicle (sham n = 4, OBX n =4), saline (sham n = 10, OBX n = 5), URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) (sham n = 13, OBX n = 9), URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) coadministered with rimonabant (1 mg/kg) (sham n = 8), or rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.) alone (sham n = 7). All animals (N = 60) received amphetamine 15 min following these pharmacological manipulations.

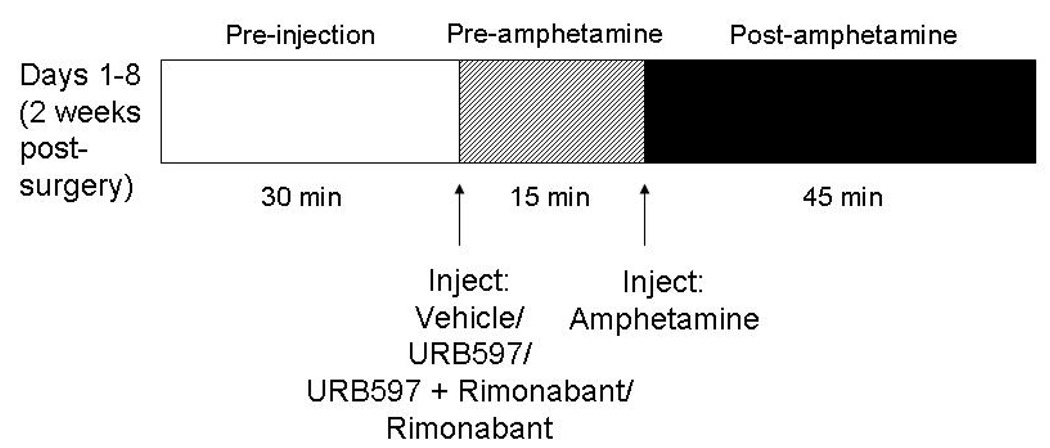

Locomotor Sensitization to Amphetamine

Locomotor sensitization to amphetamine was assessed (see Figure 1 for diagrammed procedure) using a model similar to that validated previously using cocaine (Chambers et al., 2004). At least two weeks following surgery, rats were placed individually in the center of a polycarbonate activity monitor chamber (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) measuring 44.5 × 44 × 34 cm housed in a darkened, quiet room. A 25- watt bulb shone over the chamber. Activity was automatically measured by computerized analysis of photobeam interrupts (Med Associates). Total distance traveled in the arena was obtained from the computer program and used for data analysis. Rats remained undisturbed in this chamber for 30 min. At the end of this period, according to previously randomly assigned drug conditions, rats were injected i.p. with vehicle, saline, URB597 (0.3 mg/kg), URB597 (0.3 mg/kg) coadministered with rimonabant (1 mg/kg) or rimonabant (1 mg/kg) alone. Rats were then placed back in the center of the chamber and remained undisturbed for 15 min. Activity was again automatically recorded by the computer software. At the end of this period, rats were injected with d-amphetamine sulfate (1 mg/kg i.p.) and placed back into the chamber, undisturbed, for 45 min. Activity was automatically recorded by Med Associates computer software during the entire interval. Rats were subjected to the exact same procedure once daily for a total of eight consecutive days (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Experimental design. All animals underwent the diagrammed procedure daily for 8 days beginning 14 days following OBX or sham surgery. First, animals were placed in the open field arena (30 min pre-injection interval). Then, URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.), URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) plus rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.), rimonabant alone (1 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle (i.p.) was administered and rats were placed back into the arena (15 min pre-amphetamine interval). Amphetamine (1 mg/kg i.p.) was subsequently administered and rats were placed back into the arena (45 min post-amphetamine interval). Activity levels were monitored for each of the three phases described.

Data Analysis

On each day of behavioral testing, distance traveled was recorded in three consecutive phases: (1) pre-injection open field activity (for 30 min), (2) pre-amphetamine open field activity determined after injection of vehicle/saline, URB597, URB597 coadministered with rimonabant or rimonabant alone (for 15 min), and (3) post-amphetamine open field activity (for 45 min), as diagrammed in Figure 1. Novelty-induced locomotor activity, measured during the first 30 min open field session on day 1, was analyzed with a between subjects (sham vs. OBX) Student’s t-test. Differences in average distance traveled between surgical and drug groups were analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference post hoc tests. The source of significant interactions was explained, in the case of two group comparisons, using Student’s t-tests. Friedman’s test for nonparametric repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze sensitization trends. “Distance traveled” counts obtained from activity meter software at various time points served as the dependent variable. In a small minority of cases (1% of data points or 43 out of 4320 data points), because of technical difficulties with computer software or the open field arena, data points were incomplete. Missing data values were therefore replaced with group means for that specific time point on that day. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Control Conditions

In both sham and OBX groups, distance traveled post-amphetamine did not differ between saline (vehicle for amphetamine) and ethanol: emulphor: saline (vehicle for URB597 and rimonabant) vehicle-treated animals [P > 0.05 for both comparisons]. Therefore, saline-treated animals were combined with the ethanol:emulphor:saline vehicle-treated animals to form what will be referred to hereafter as the “vehicle”-treated control group.

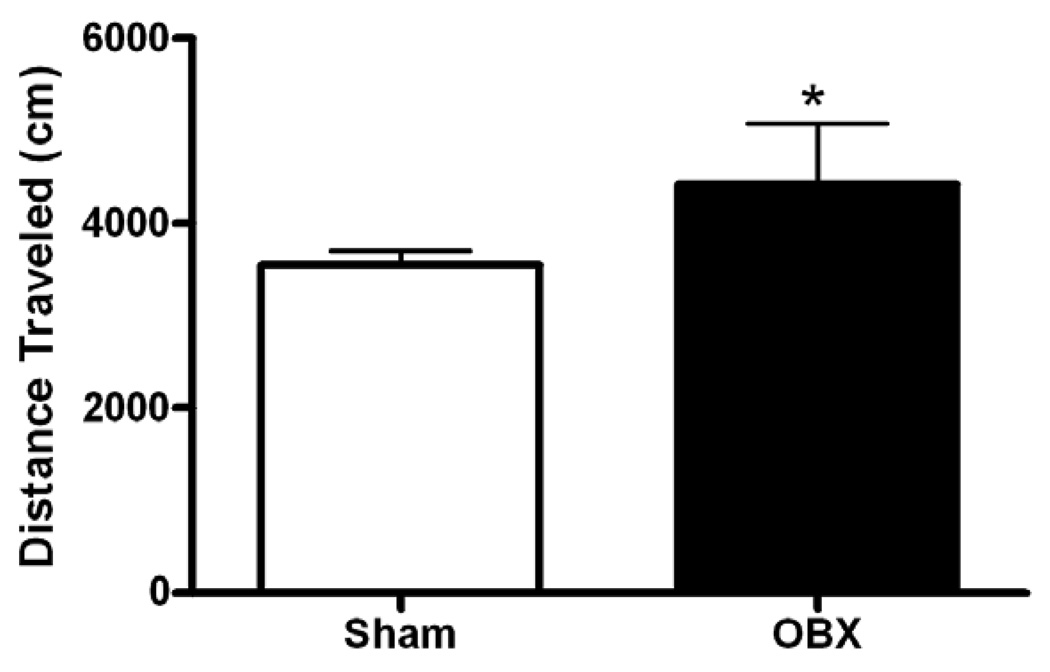

Exposure to Novel Open Field (Day 1)

To verify that the OBX animals in our study exhibited characteristic hyperlocomotor responses to novelty, locomotor behavior elicited by exposure to a novel open field was measured in OBX and sham-operated rats. OBX animals exhibited 24.5 % greater locomotor activity than sham rats during the 30 min exposure to the novel open field arena (t58 = 1.82, P < 0.05, one-tailed) (see Figure 2), as described in other published reports (Klein and Brown, 1969; van Riezen and Leonard, 1990).

Figure 2.

Novelty-induced locomotor activity in olfactory bulbectomized and sham-operated rats. Olfactory bulbectomy induced a heightened locomotor response to a novel open field relative to sham surgery during the initial open field session (day 1). Data are Mean + SEM; *P < 0.05 versus sham (t-test).

Repeated Exposure to Open Field (Day 2–7 Pre-injection Sessions)

To confirm that OBX rats behaved similarly to sham-operated rats when placed in an open field arena that was no longer novel, distance traveled was assessed on days 2–7 during the 30 min pre-injection sessions. Olfactory bulbectomy did not affect locomotor activity during this period. Locomotor activity declined similarly in both OBX and sham animals that received vehicle over consecutive days of testing (F6,126 = 13.87, P = 0.001). Moreover, cannabinoid pharmacological manipulations did not affect distance traveled in sham or OBX animals during the 30 min habituation session on days 2–7 (P > 0.05 for both analyses) (data not shown). Therefore, effects of URB597 and rimonabant on amphetamine sensitization (on day 2–7) did not depend upon locomotor responses elicited in response to the open field itself.

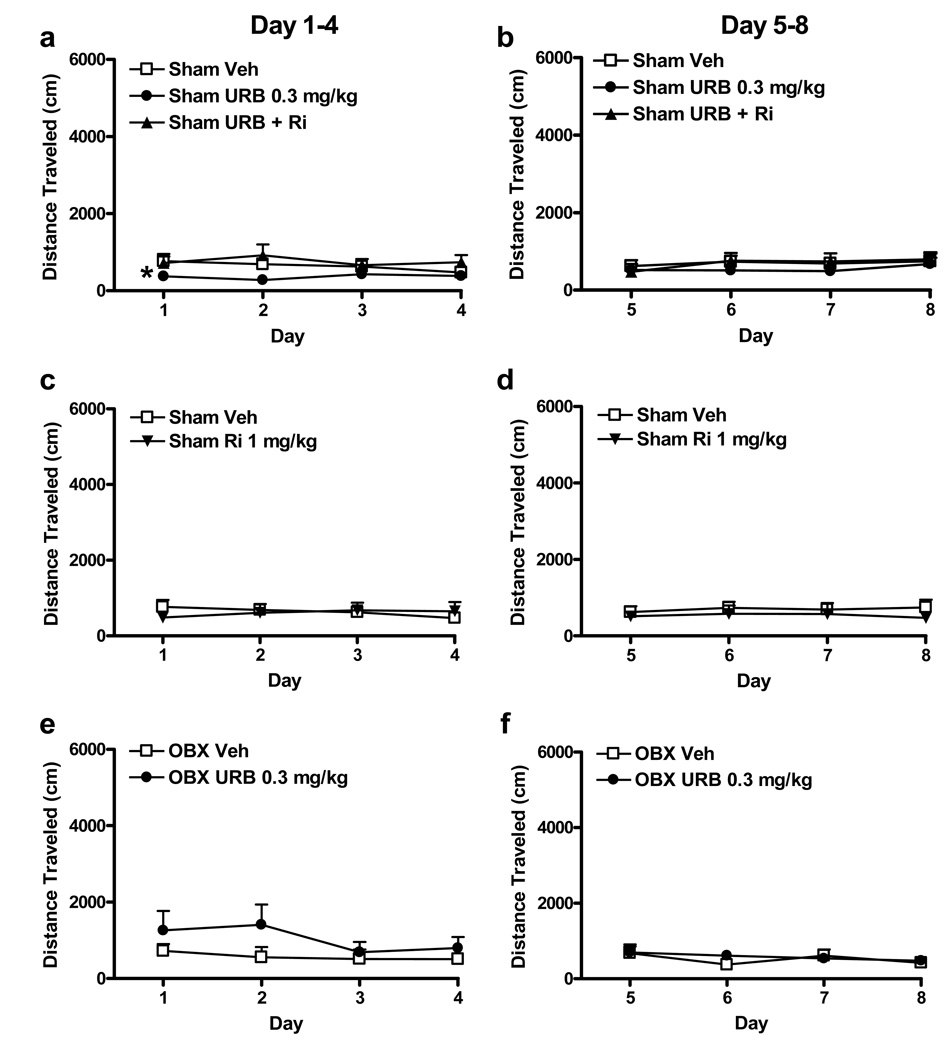

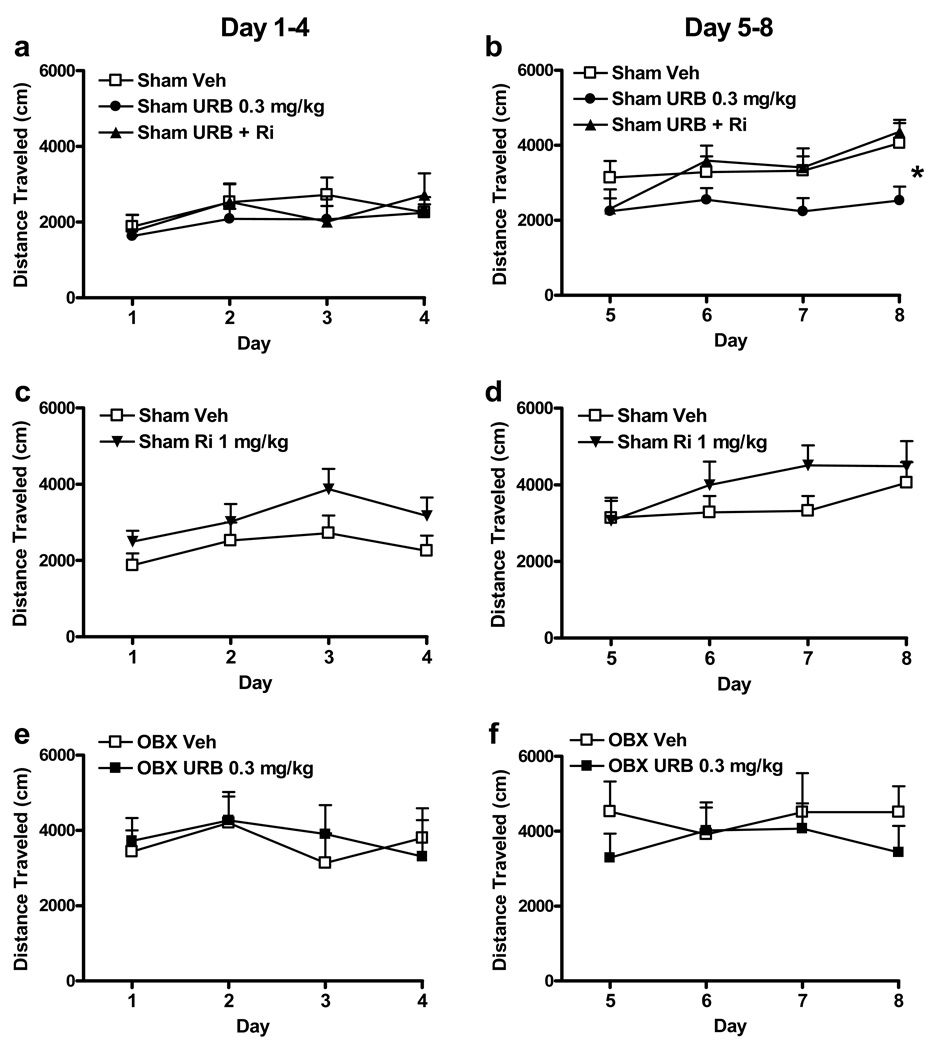

Cannabinoid Pharmacological Manipulations (Pre-amphetamine Sessions)

The impact of cannabinoid pharmacological manipulations on basal locomotor activity was evaluated in pre-amphetamine sesssions (see Figure 1) to enable us to separate effects on basal locomotor activity from effects on locomotor sensitization to amphetamine. For this analysis, distance traveled during the 15 min pre-amphetamine interval was assessed over eight consecutive days of testing. Animals received once daily administration of either vehicle, URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.), URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) coadministered with rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.), or rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.) alone. Olfactory bulbectomy did not affect distance traveled during this pre-amphetamine interval in animals that received vehicle (P > 0.05) (data not shown). The first and last four days of preamphetamine locomotor activity were analyzed separately to determine whether possible locomotor effects of URB597, observed during the preamphetamine session, could explain any effects of URB597 on locomotor sensitization to amphetamine (see post-amphetamine session results below). In sham animals, URB597 produced a modest but reliable decrease in distance traveled during the preamphetamine session during the first four days of testing (F2, 32 = 6.11, P < 0.01). This effect was blocked by coadministration of rimonabant (P < 0.05 for both post hoc comparisons) (see Figure 3a). However, URB597 did not affect locomotor activity during the preamphetamine interval during the last four days of testing (P > 0.05) (see Figure 3b). This latter interval corresponds to the period during which URB597 suppressed locomotor sensitization to amphetamine in sham animals (see post-amphetamine session results below). Thus, effects of URB597 on amphetamine sensitization in our study cannot be attributed merely to acute locomotor effects of the FAAH inhibitor. In sham animals, rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.) did not alter distance traveled during the pre-amphetamine sessions relative to vehicle over either the first four (P > 0.05) or the last four (P > 0.05) days of the sensitization protocol (see Figure 3c, d). Similar conclusions were reached when locomotor activity was analyzed across the entire eight consecutive days of testing (data not shown). In OBX animals, URB597 did not alter distance traveled during the preamphetamine sessions relative to vehicle over either the first four (P > 0.05) or last four (P > 0.05) days of testing (see Figure 3e, f). Similar conclusions were reached when locomotor activity was assessed across all eight consecutive days of testing.

Figure 3.

Activity during the pre-amphetamine interval in sham-operated and olfactory bulbectomized rats. In sham animals, URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) decreased pre-amphetamine locomotor activity (a) on days 1–4 of the sensitization protocol. This effect was blocked by rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p). P < 0.01 (ANOVA), *P < 0.05 for each comparison (Fisher's PLSD post hoc). (b) No changes in pre-amphetamine locomotor activity were observed on days 5–8 of testing. In sham animals, rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.) alone did not alter pre-amphetamine locomotor activity relative to vehicle during either the (c) first four or (d) last four days of testing. In OBX rats, URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) did not affect pre-amphetamine locomotor activity relative to vehicle during either the (e) first four or (f) last four days of testing. Data are Mean + SEM.

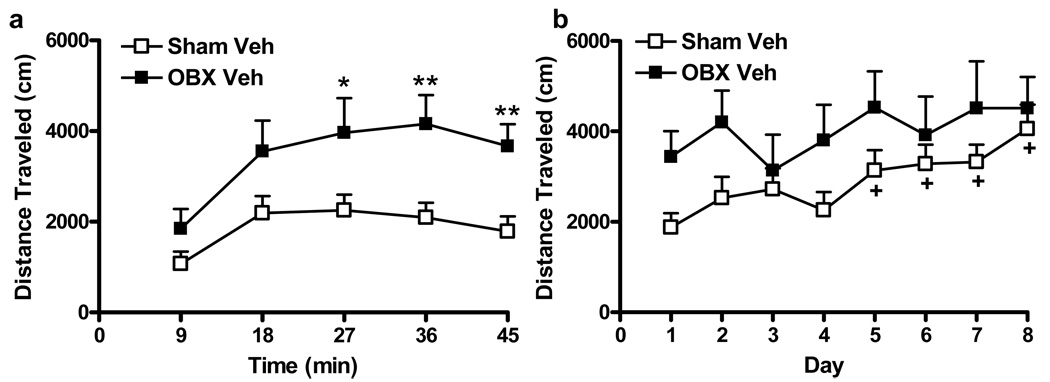

Amphetamine-induced Locomotor Activity (Post-amphetamine Sessions)

To determine the initial locomotor response to amphetamine, distance traveled during the first post-amphetamine session was compared in OBX and sham-operated rats (i.e. on day 1). On day 1, OBX rats receiving vehicle showed greater locomotor responses to amphetamine than sham-operated rats that similarly received vehicle (F1, 21 = 6.88, P < 0.05) (see Figure 4a). Amphetamine-induced locomotor activation increased but then leveled out over the 45 min observation interval in both groups (F4, 84 = 27.36, P < 0.001) (see Figure 4a). Olfactory bulbectomy differentially increased distance traveled over time on the first day of amphetamine administration (F4, 84 = 3.72, P < 0.01); OBX animals traveled more than shams from 27–45 min post-amphetamine administration (P < 0.05 for all comparisons) (see Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Olfactory bulbectomy alters the development of amphetamine sensitization (a) Olfactory bulbectomy induces a heightened locomotor state in response to initial (day 1) amphetamine (1 mg/kg i.p.) administration P < 0.01 (ANOVA) *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus sham (t-test) (b) Sham animals develop a typical sensitization to repeated injections of amphetamine, as demonstrated by increased locomotor activity (P < 0.001 (Friedman's), +P < 0.05 versus day 1 (Dunn's multiple comparisons). By contrast, OBX animals are presensitized to amphetamine. Data are Mean + SEM.

To determine the impact of olfactory bulbectomy on amphetamine sensitization, amphetamine-induced distance traveled was compared in vehicle-treated OBX and sham-operated rats over all eight days of testing. A time-dependent sensitization to amphetamine developed in sham-operated groups (Fr8, 14=32.64, P < 0.001); distance traveled on days 5–8 was greater than that observed on day 1 (P < 0.05 for all comparisons, Dunn’s multiple comparisons), By contrast, OBX animals did not further sensitize to locomotor effects of amphetamine (P > 0.05) (see Figure 4b).

Drug Effects on the Development of Amphetamine-induced Sensitization

OBX animals responded very differently to both amphetamine and URB597 relative to sham-operated rats. Therefore, the impact of cannabinoid pharmacological manipulations on amphetamine sensitization was evaluated in each surgical group separately. Sham animals that received vehicle sensitized to the locomotor effects of amphetamine; amphetamine-induced distance traveled was greater during the last four days of the sensitization protocol than during the first four (Fr8,14 = 35.1, P < 0.0001, Friedman’s test). Distance traveled on day 8 was greater than that observed on days 1, 3 or 4. Amphetamine-induced locomotor activity was also greater on days 5–7 than on day 1 (P < 0.05 for all comparisons, Dunn’s multiple comparisons) (see Figure 5a, b). Furthermore, in sham animals that received URB597, amphetamine-induced locomotor sensitization did not occur (P > 0.05, Friedman’s). Therefore, effects of cannabinoid pharmacological manipulations were analyzed during the first four and last four days of the sensitization protocol separately to best describe the impact of URB597 treatment on the development of amphetamine sensitization.

Figure 5.

Effects of cannabinoid pharmacological manipulations on amphetamine sensitization in sham-operated and olfactory bulbectomized rats (a) Locomotor responses to amphetamine (1 mg/kg i.p.) are similar in sham animals that received vehicle (i.p.), URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.), or URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) coadministered with rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.) during the first four days of the sensitization protocol. (b) In sham animals, URB597 (0.3 mg/kg i.p.) attenuated amphetamine sensitization relative to vehicle (i.p.) during the last four days of the sensitization protocol (*P < 0.05, ANOVA). This effect was blocked by rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.) (P < 0.05 for each comparison, Fisher's PLSD post hoc). Rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.) did not affect the development of amphetamine sensitization during either the (c) first four or (d) the last four days of testing. In OBX animals, URB597 did not alter the development of amphetamine sensitization during either the (e) first four or (f) last four days of testing. Data are Mean + SEM.

In sham animals, amphetamine-induced distance traveled was not affected by cannabinoid pharmacological manipulations during the first four days of testing (P > 0.05) (see Figure 5a). Pharmacological manipulations did, however, alter amphetamine-induced distance traveled during the last four days of the sensitization protocol (F2, 32 = 3.72, P < 0.05). Shams that received URB597 traveled less than those that received vehicle and this effect was blocked by rimonabant (P < 0.05 for both post hoc comparisons) (see Figure 5b). In sham animals, locomotor sensitization to repeated amphetamine administration was observed during the last four days of testing (F3, 96 = 5.73, P = 0.001) (see Figure 5b). In sham animals, rimonabant alone did not affect the development of amphetamine sensitization relative to vehicle during either the first (P > 0.05) or last four (P > 0.05) days of testing (see Figure 5c, d). Amphetamine-induced locomotor sensitization was similarly increased in sham-operated groups receiving either vehicle or rimonabant. Identical conclusions were reached when distance traveled was analyzed across the first four (F3, 57 = 3.48, P < 0.05) or the last four (F3, 57 = 3.44, P < 0.05) days of the sensitization protocol (see Figure 5c, d) or across all 8 consecutive days of testing.

In OBX animals, amphetamine-induced distance traveled was similar across all 8 days of amphetamine administration (P > 0.05), reflecting the lack of further sensitization to amphetamine in OBX animals (see Figure 5e, f). Furthermore, URB597 did not alter the development of amphetamine sensitization in OBX rats during either the first (P > 0.05) or last four (P > 0.05) days of the sensitization protocol (see Figure 5e, f).

DISCUSSION

The olfactory bulbectomized rat is a model in which dopaminergic transmission is profoundly altered. OBX rats exhibit increases in dopamine-dependent behaviors such as an increased behavioral sensitivity to novelty (Klein and Brown, 1969; van Riezen and Leonard, 1990) and drugs of abuse (Gaddy and Neill, 1976; Holmes et al., 2002; Chambers et al., 2004). Olfactory bulbectomy also increases dopaminergic activity in the ventral striatum (Gilad and Reis, 1979; Holmes, 1999; Lingham and Gottesfeld, 1986; Masini et al., 2004). The olfactory bulbectomy model was therefore employed to examine the role of the endocannabinoid signaling system in modulating behaviors known to rely at least partially on dopaminergic transmission: locomotion in response to novelty and development of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine. In line with other studies (Klein and Brown, 1969; van Riezen and Leonard, 1990), OBX animals exhibited greater locomotion than sham animals in response to novelty. Sham and OBX animals also responded quite differently to the FAAH inhibitor URB597. In sham animals, URB597 decreased locomotor activity during the preamphetamine interval in a CB1-dependent manner. By contrast, the FAAH inhibitor did not alter locomotor activity of OBX animals over the same interval. Sham animals also exhibited a time-dependent sensitization to amphetamine that was suppressed by URB597 in a CB1-dependent manner. In agreement with previous research (Gaddy and Neill, 1976), OBX animals in our study displayed a heightened locomotor response to acute treatment with amphetamine. Our results verify and extend this observation by documenting that, in contrast to shams, further sensitization to amphetamine was absent in OBX animals following repeated amphetamine treatment. Our data suggest that OBX animals are “presensitized” to indirect dopaminergic agonists. Thus, sensitization could not be further enhanced in OBX animals with repeated amphetamine treatment, as suggested previously with repeated cocaine treatment (Chambers et al., 2004). These observations suggest that dopaminergic sensitivity is maximal in OBX animals prior to pharmacological manipulations. This notion is also supported by evidence that dopamine signaling is enhanced in the ventral striatum of OBX rats (Gilad and Reis, 1979; Holmes, 1999; Lingham and Gottesfeld, 1986; Masini et al., 2004). Furthermore, OBX animals were insensitive to the FAAH inhibitor URB597, which suppressed amphetamine sensitization in sham-operated rats. Rimonabant alone did not affect sensitization to amphetamine. The rimonabant dose employed in the current study (1 mg/kg i.p.) did not alter locomotor activity elicited by exposure to either the open field or to amphetamine. This observation is consistent with previous work documenting that rimonabant (1 mg/kg i.p.) blocks pharmacological effects of URB597 without altering basal locomotor activity or inducing anxiogenic-like behavior (Jarbe et al., 2006; Moise et al; 2008; Patel and Hillard, 2006).

In other studies, the CB1 antagonist/inverse agonist AM251 decreased (Thiemann et al., 2008a) whereas rimonabant increased (Masserano et al., 1999); Thiemann et al., 2008b) locomotor responses to amphetamine in otherwise naive animals. In our study, a lower dose (1 mg/kg i.p.) of rimonabant was administered than that used in the study by Thiemann et al. (2008b). Thus, this behaviorally inactive dose of rimonabant, administered alone, did not affect locomotor activity in our study. Differences in the effects of AM251 and rimonabant may be explained by the fact that these drugs are known to have inverse agonist properties and may differentially block CB1 receptors versus other off-target sites (Pertwee, 2005). However, off-target effects cannot explain the ability of rimonabant to block the effects of a FAAH inhibitor in our study.

In sham-operated rats, URB597 decreased the development of amphetamine sensitization in a CB1-dependent manner. This observation contrasts with the decrease in amphetamine sensitization observed following treatment with AM251 (Thiemann et al., 2008a). Inhibition of anandamide hydrolysis with URB597 (Kathuria et al. 2003) could be expected to exert an effect opposite to that of CB1 blockade. However, URB597 did not affect development of amphetamine sensitization until day 5 of our paradigm. Subchronic administration of URB597 may increase extracellular anandamide concentrations more effectively in an environment in which the endocannabinoid system is better able to regulate dopaminergic transmission (i.e. elicitied in response to novelty or amphetamine exposure). This enhanced modulation may not be apparent until development of amphetamine sensitization is well under way (i.e. approximately day 5 of amphetamine administration in the current study). By contrast, administration of AM251, a CB1 antagonist/inverse agonist, would exert a more direct, and thus more rapid, effect on CB1 receptors. Notably, FAAH inhibition had no effect on the development of amphetamine sensitization in OBX animals.

OBX animals exhibited a presensitized locomotor state that is likely to result from an inability of the endocannabinoid system to modulate dopaminergic activity. The olfactory bulbs provide the major cortical input to the olfactory tubercle component of the ventral striatum (Heimer et al., 1995). Olfactory bulbectomy thus removes a major source of glutamatergic afferents in the striatum and possible source of the anandamide synthesizing enzyme NAPE-PLD. Thus, in OBX rats, FAAH inhibition may be unable to reinstate anandamide levels to levels observed in sham-operated rats. Consistent with this hypothesis, OBX animals show altered novelty-induced glutamate release in the striatum relative to sham-operated rats (Ho et al., 2000), providing further evidence for glutamatergic dysregulation in this model. Alternatively, olfactory bulbectomy may disrupt the synthesis of endocannabinoids in the ventral striatum and/or other regions that are deafferented by olfactory bulbectomy. These alterations would be expected to induce lower than optimal levels of endocannabinoids. Finally, limbic structures (e.g. amygdala, piriform and entorhinal cortices) that are deafferented by olfactory bulbectomy (Kelly et al., 1997) may disrupt regulatory input downstream from these structures into the dopaminergic system, including striatal projection neurons. Our data suggest that this disruption may render OBX animals more vulnerable to stimuli, such as novelty and amphetamine, which heighten dopaminergic transmission.

URB597 transiently decreased pre-amphetamine locomotor activity in sham-operated but not OBX animals. This suppression, however, dissipated over time; URB597 no longer suppressed pre-amphetamine locomotor activity by days 4–8 of the sensitization protocol. This interval occurred immediately after injection and may reflect a URB597-mediated acute locomotor effect (i.e. revealed under conditions in which locomotor responses to novelty have undergone habituation following repeated exposure to the open field). As with sensitization, OBX animals were insensitive to this putative locomotor effect of URB597. Interestingly, in sham-operated rats, FAAH inhibition did not influence the development of amphetamine sensitization relative to vehicle-treated controls until later days in the sensitization protocol. Our findings demonstrate that subchronic (8 days) administration of URB597 attenuates the development of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine in sham-operated rats. However, this modulation is notably absent or impaired in OBX rats in which the dopaminergic system is presensitized to stimuli, such as novelty and amphetamine, which heighten dopaminergic transmission. Our data suggest that endocannabinoids and fatty-acid amide hydrolase regulate plasticity in response to stimuli that enhance dopaminergic transmission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by DA021644, DA022478, DA022702 (to A.G.H.) and a University of Georgia Dissertation Completion Assistantship and an ARCS Foundation Scholarship (to S.A.E.).

REFERENCES

- Bortolato M, Mangieri RA, Fu J, Kim JH, Arguello O, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, Piomelli D. Antidepressant-like activity of the fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor URB597 in a rat model of chronic mild stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(10):1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D, Battista N, Rossi S, Mercuri NB, Finazzi-Agro A, Bernardi G, Calabresi P, Maccarrone M. A critical interaction between dopamine D2 receptors and endocannabinoids mediates the effects of cocaine on striatal gabaergic Transmission. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(8):1488–1497. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers RA, Sheehan T, Taylor JR. Locomotor sensitization to cocaine in rats with olfactory bulbectomy. Synapse. 2004;52(3):167–175. doi: 10.1002/syn.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384(6604):83–87. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Demarest K, Patricelli MP, Bracey MH, Giang DK, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(16):9371–9376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Mandelbaum A, Etinger A, Mechoulam R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258(5090):1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Fontana A, Cadas H, Schinelli S, Cimino G, Schwartz JC, Piomelli D. Formation and inactivation of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide in central neurons. Nature. 1994;372(6507):686–691. doi: 10.1038/372686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Petrosino S. Endocannabinoids and the regulation of their levels in health and disease. Current opinion in lipidology. 2007;18(2):129–140. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32803dbdec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertová M, Cravatt BF, Elphick MR. Comparative analysis of fatty acid amide hydrolase and CB1 cannabinoid receptor expression in the mouse brain: evidence of a widespread role for fatty acid amide of endocannabinoid signaling. Neuroscience. 2003;119:481–496. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy JR, Neill DB. Enhancement of the locomotor response to d-amphetamine by olfactory bulb damage in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1976;5(2):189–194. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(76)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdeman GL, Ronesi J, Lovinger DM. Postsynaptic endocannabinoid release is critical to long-term depression in the striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(5):446–451. doi: 10.1038/nn832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad GM, Reis DJ. Collateral sprouting in central mesolimbic dopamine neurons: biochemical and immunocytochemical evidence of changes in the activity and distrubution of tyrosine hydroxylase in terminal fields and in cell bodies of A10 neurons. Brain Res. 1979;160(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90597-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida A, Parsons LH, Kerr TM, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Navarro M, Piomelli D. Dopamine activation of endogenous cannabinoid signaling in dorsal striatum. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(4):358–363. doi: 10.1038/7268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L, Zahm DS, Alheid GF. Basal Ganglia. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. 2nd Ed. New York: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 579–628. [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci. 1991;11(2):563–583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00563.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Little MD, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(5):1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho YJ, Chang YC, Liu TM, Tai MY, Wong CS, Tsai YF. Striatal glutamate release during novelty exposure-induced hyperactivity in olfactory bulbectomized rats. Neuroscience letters. 2000;287(2):117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Herkenham M. Localization of cannabinoid CB(1) receptor mRNA in neuronal subpopulations of rat striatum: a double-label in situ hybridization study. Synapse. 2000;37(1):71–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200007)37:1<71::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes PV. Olfactory bulbectomy increases prepro-enkephalin mRNA levels in the ventral striatum in rats. Neuropeptides. 1999;33(3):206–211. doi: 10.1054/npep.1999.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes PV, Masini CV, Primeaux SD, Garrett JL, Zellner A, Stogner KS, Duncan AA, Crystal JD. Intravenous self-administration of amphetamine is increased in a rat model of depression. Synapse. 2002;46(1):4–10. doi: 10.1002/syn.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathuria S, Gaetani S, Fegley D, Valino F, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, La Rana G, Calignano A, Giustino A, Tattoli M, Palmery M, Cuomo V, Piomelli D. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 2003;9(1):76–81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JP, Wrynn AS, Leonard BE. The olfactory bulbectomized rat as a model of depression: an update. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;74(3):299–316. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D, Brown TS. Exploratory behavior and spontaneous alternation in blind and anosmic rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1969;68(1):107–110. doi: 10.1037/h0027657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Cerebellar depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition is mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. J Neurosci. 2001;21(20):RC174. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-j0005.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingham RB, Gottesfeld Z. Deafferentation elicits increased dopamine-sensitive adenylate cyclase and receptor binding in the olfactory tubercle. J Neurosci. 1986;6(8):2208–2214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-08-02208.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailleux P, Vanderhaeghen JJ. Distribution of neuronal cannabinoid receptor in the adult rat brain: a comparative receptor binding radioautography and in situ hybridization histochemistry. Neuroscience. 1992;48(3):655–668. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90409-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco EM, Adriani W, Canese R, Podo F, Viveros MP, Laviola G. Enhancement of endocannabinoid signalling during adolescence: Modulation of impulsivity and long-term consequences on metabolic brain parameters in early maternally deprived rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86(2):334–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini CV, Holmes PV, Freeman KG, Maki AC, Edwards GL. Dopamine overflow is increased in olfactory bulbectomized rats: an in vivo microdialysis study. Physiol Behav. 2004;81(1):111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masserano JM, Karoum F, Wyatt RJ. SR 141716A, a CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonist, potentiates the locomotor stimulant effects of amphetamine and apomorphine. Behav Pharmacol. 1999;10(4):429–432. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199907000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monory K, Blaudzun H, Massa F, Kaiser N, Lemberger T, Schutz G, Wotjak CT, Lutz B, Marsicano G. Genetic dissection of behavioural and autonomic effects of Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol in mice. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(10):2354–2368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moise AM, Eisenstein SA, Astarita G, Piomelli D, Hohmann AG. An endocannabinoid signaling system modulates anxiety-like behavior in male Syrian hamsters. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1209-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyilas R, Dudok B, Urban GM, Mackie K, Watanabe M, Cravatt BF, Freund TF, Katona I. Enzymatic machinery for endocannabinoid biosynthesis associated with calcium stores in glutamatergic axon terminals. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1058–1063. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5102-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Maejima T, Kano M. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signals from depolarized postsynaptic neurons to presynaptic terminals. Neuron. 2001;29(3):729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Hillard CJ. Pharmacological evaluation of cannabinoid receptor ligands in a mouse model of anxiety: further evidence for an anxiolytic role for endogenous cannabinoid signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318(1):304–311. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Inverse agonism and neutral antagonism at cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Life Sci. 2005;76(12):1307–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D. The endocannabinoid system: a drug discovery perspective. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6(7):672–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella N, Schweitzer P, Piomelli D. A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature. 1997;388(6644):773–778. doi: 10.1038/42015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann G, Di Marzo V, Molleman A, Hasenohrl RU. The CB(1) cannabinoid receptor antagonist AM251 attenuates amphetamine-induced behavioural sensitization while causing monoamine changes in nucleus accumbens and hippocampus. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008a;89(3):384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann G, van der Stelt M, Petrosino S, Molleman A, Di Marzo V, Hasenohrl RU. The role of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor and its endogenous ligands, anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, in amphetamine-induced behavioural sensitization. Behav Brain Res. 2008b;187(2):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Riezen H, Leonard BE. Effects of psychotropic drugs on the behavior and neurochemistry of olfactory bulbectomized rats. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;47(1):21–34. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001;410(6828):588–592. doi: 10.1038/35069076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]