Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this study was to determine the clinical and therapeutic characteristics of women with a primary peritoneal carcinoma (PPC).

Materials and Methods

A retrospective clinical study was conducted to evaluate 22 women diagnosed with a PPC from 1993 to 2007 at the Hospitals of The Catholic University of Korea. Diagnoses were based on the Gynecologic Oncology Group criteria and clinical data. We collected patient clinicopathological data including age, presenting symptoms, pretreatment CA-125 values (U/ml), clinical stage (based on the FIGO stage), performance status (using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale), whether cytoreductive surgery was optimal or not, types of chemotherapy and response to treatment. We evaluated the clinical characteristics and response to treatment, time to treatment failure and overall survival.

Results

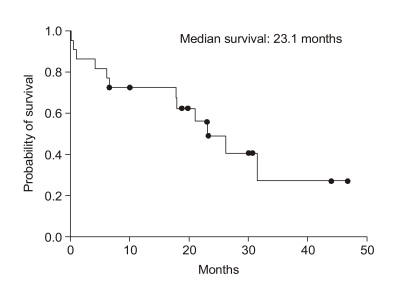

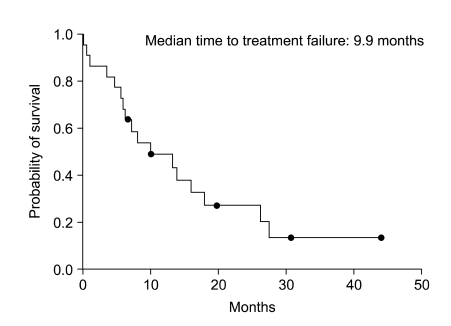

The median overall survival of all patients was 23.1 months. The estimated 3-year survival rate was 29% (SE, 13%). The response rate to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy was 79% and the median time to treatment failure was 9.9 months (95% confidence interval, 1.38~18.4 months). By univariate and multivariate analysis, performance status was the only significant factor associated with overall survival (p<0.05).

Conclusion

We evaluated the clinical characteristics and treatment response of patients with a primary peritoneal carcinoma. Our results showed that it is possible to achieve long-term survival in patients with PPC. A further clinical study is to need to establish clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Primary peritoneal carcinoma, Clinical characteristics

INTRODUCTION

Primary peritoneal carcinoma (PPC) was first described in 1959 by Swerdlow (1). This cancer spreads widely inside the peritoneal cavity and mostly involves the omentum. However, it spares or only minimally involves the ovaries. Histologically, it is indistinguishable from primary epithelial ovarian carcinoma and is diagnosed in the absence of other identifiable primary sites (2). Although the histopathological and clinical features of PPC have been described in several reports, the behavior of this disease entity remains obscure (3~6). Most investigators have described a similar clinical behavior of PPC and papillary serous ovarian carcinoma (7~9). In order to determine the characteristics and prognosis in patients with a primary peritoneal carcinoma, we conducted a retrospective analysis of cases that were treated at our institution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a retrospective review of 22 patients with primary peritoneal carcinoma (PPC) diagnosed from 1993 to 2007 at the Hospitals of The Catholic University of Korea. A diagnosis of PPC was reviewed by evaluation of the clinical and pathological findings, and was based on the Gynecology Oncology Group (GOG) criteria as described in the study by Bloss et al(6) that included the following: (i) the ovaries were either absent or normal in size; (ii) the involvement of the extraovarian sites was greater than the involvement of the surface of either ovary; (iii) an absence of a deep-seated invasive ovarian carcinoma or invasive disease in the ovarian cortical stroma with tumors that measured less than 5×5 mm2, (iv) the histopathological and cytological characteristics of the tumors were similar to that for epithelial ovarian cancer. Although GOG criteria are based on surgical and pathological findings, in this study we included the clinical diagnosis of PPC based on computed tomography (CT) and histopathology reports.

We collected clinical and pathological data of the patients. The information included the age at diagnosis, presenting symptoms, pretreatment CA-125 values (U/ml), clinical or surgical stage (based on the FIGO stage), performance status (using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale), whether cytoreductive surgery was optimal (i.e., ≤1.0 cm for the largest residual tumor mass) or not (i.e., >1.0 cm for the largest residual tumor mass), the type of chemotherapy and response to treatment, the date of death or the date of the last follow-up, and patient condition at the last follow-up. Evaluation of the clinical response to chemotherapy was based on WHO criteria (10). The follow-up information was updated until July 31, 2007, based on a review of the medical record, or by direct contact with patients or their relatives.

Overall survival was determined from the time of the initial diagnosis to the time of death or date of last contact. The time to treatment failure was from the date of diagnosis to the date of progressive disease, recurrence or death. Disease progression or recurrence were defined as a new lesion or an increased size of the pre-existing lesion on an image or an elevated CA-125 level in two consecutive tests, if no evaluable or measurable lesion was present. Estimated overall survival curves were calculated using the method of Kaplan-Meier, and comparisons of survival distribution among various factors were made using the log rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 11.0).

RESULTS

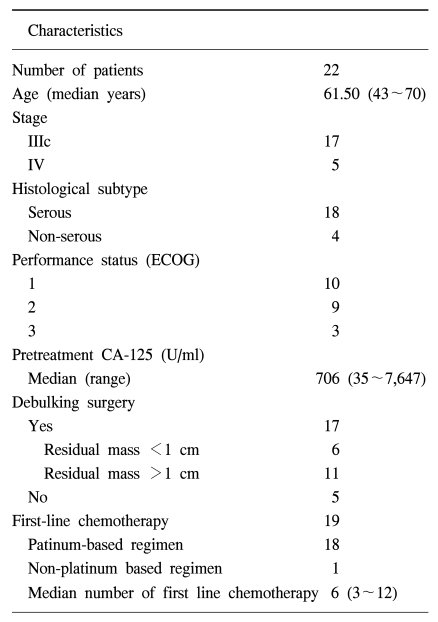

Twenty-two patients were diagnosed with PPC and were treated. A CT scan was performed before treatment in all patients. All patients had normal sized ovaries (less than 4 cm) with extensive involvement of the peritoneum including ascites. The clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The median patient age was 62 years (range 43~70 years). The most common presenting symptoms were abdominal distension and pain. At pretreatment, the CA-125 level of one patient was at the upper limit of the normal range of CA-125 values in our laboratory (normal range, 0 to 35 U/ml); the other patients had elevated pretreatment CA-125 values and the median value was 706 IU/ml (range, 35~7647 IU/ml). However, during treatment, the CA-125 level of the patient at the upper limit of the normal range decreased.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

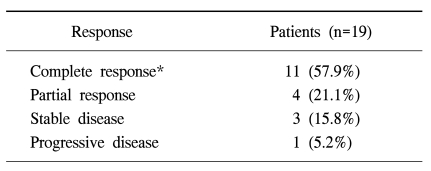

Cytoreductive surgery was performed initially in 17 patients. Residual disease was optimal in 6 patients and suboptimal in 11 patients. The histological subtype was predominantly the serous type (81.8%). One patient had a mucinous type and three patients had poorly differentiated types. Three patients died before commencing chemotherapy, two patients had disease progression during diagnosis and one patient died due to postoperative complications. Nineteen patients received first-line chemotherapy with a platinum-based agent, 15 patients received platinum and taxane, three patients received platinum and cyclophosphamide and one patient received a non-platinum containing regimen. The median number of courses of first-line chemotherapy was 6 (range 3~12). The patient response to primary chemotherapy is described in Table 2. Of the13 patients that received second-line chemotherapy, 6 patients achieved a partial or complete response.

Table 2.

Response to first-line chemotherapy

*includes two patients with optimal cytoredctive surgery.

The median duration of follow-up was 19.9 months (range 0.2~47.1 months). At the time of the last follow up, eleven (50%) patients died from the disease, six (27.3%) patients were alive with disease and four (18.2%) patients were alive without disease, and one (5%) patient died due to postoperative complications.

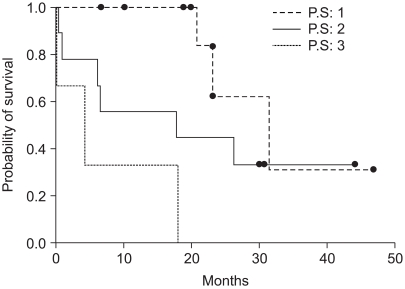

For all patients, the median overall survival was 23.1 months and the estimated 3-year survival rate was 29% (SE, 13%) (Fig. 1) and the median time to treatment failure was 9.9 months (95% confidence interval, 1.38~18.4) (Fig. 2). However, except for three patients that did not receive chemotherapy, the median overall survival was 26.3 months, the estimated 3-year survival was 36% (SE, 14%) and the median time to treatment failure was 13.8 months (95% confidence interval, 6.54~21.05). The relapsed sites were mainly the peritoneal cavity and liver. We tested the prognostic factors that affected survival time such as age, performance status, stage, whether cytoreductive surgery was optimal or not, and histological subtype. The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses showed that the performance status was the only significant factor associated with overall survival (p<0.05, Fig. 3). However, there was also a tendency toward significance for optimal cytoreductive surgery (p=0.08).

Fig. 1.

Overall survival curve for 22 patients with a primary peritoneal carcinoma.

Fig. 2.

Time to treatment failure.

Fig. 3.

Survival curves for patients with PPC according to performance status. A statistically significant difference was detected (p<0.05). P.S: performance status.

DISCUSSION

A primary peritoneal carcinoma is referred to by many names including a mesothelioma, papillary carcinoma of the peritoneum, serous surface papillary carcinoma and extraovarian papillary serous carcinoma; these many names reflect a debate on the histogenesis and clinical behavior of the tumor. With the use of histopathological criteria, these tumors appear more like M?llerian neoplasms than classic mesotheliomas (7,11,12). Surgical exploration provides a diagnosis, staging evaluation and treatment of patients with PPC. Assessment of patients should be directed at identifying potential primary sites, including the ovaries and mammary glands as well as pancreatic and gastrointestinal lesions (7). Histopathological and cytological characteristics of the tumor are predominantly the serous type (13). However other varieties of Müllerian differentiation have been reported, including clear cell, endometrioid, mucinous, and mixed Müllerian mesodermal tumors (7).

The treatment of a PPC is based on cytoreductive surgery and platinum based chemotherapy. Optimal cytoreduction is the primary goal of the surgical procedure. Excision of all visible implants is the hallmark of the cytoreductive efforts (7). In this study, 6 (27.2%) patients received optimal cytoreductive surgery. In a series of 18 patients reported by Taus et al., the rate of extensive involvement in the upper abdomen was high and this finding led to the performance of an exploratory laparotomy in 38% of the patients (14). In a series reported by Fromm et al., the rate of successful debulking surgery was only 41% (3). The chemotherapeutic regimen used for PPC should be similar to that used in ovarian cancer. The use of platinum- based chemotherapeutic regimens improves patient survival; long-term survival can be achieved in some patients with the use of platinum-based chemotherapy (3,5,15). Bloss et al. (16) demonstrated in a phase II trial, that a PPC was similar to an epithelial ovarian carcinoma in response to treatment, toxicity and overall survival. Based on the results of this trial, the GOG has included patients with PPC in many of its subsequent ovarian cancer trials. Our results also showed that the use of platinum-based chemotherapy increases the survival and might achieve long-term survival; the estimated 3-year survival rate was 36%.

Currently, the CA-125 antigen is considered the most effective tumor marker for a primary peritoneal carcinoma (2). Skates et al. (17) reported a case of a patient that, based on a rising level of CA-125, received surgery and was found to have a peritoneal papillary serous carcinoma. Altaras et al. (2) described that CA-125 measurements correlated with the clinical status of disease. Similar to ovarian cancer, patients with PPC have CA-125 values that are useful for diagnosis and follow up of response to therapy. However, it should be noted that not all primary peritoneal carcinomas exhibit increasing levels of CA-125; there is report where CA-125 testing did not detect a primary peritoneal carcinoma before bulky widespread dissemination (18).

The clinical presentation of patients with PPC reported in the current study are in agreement with those previously reported studies (2,4~6,11,12,15,19). The most common presenting symptoms were abdominal distension and pain. Ascites was the most common sign detected on examination.

Some investigators have reported that by univariate analysis, overall survival depends on age at diagnosis, performance status and degree of debulking achieved at the primary cytoreductive surgery. However, multivariate analysis showed that only performance status and debulking surgery correlated with overall survival and these results were statistically significant (20).

Although the study population was smaller than other previous studies, the median survival reported in the current study was greater than that reported in previous studies (2,5,6, 12,19,21), between 11.3~17.8 months. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings.

CONCLUSIONS

We have evaluated the clinical characteristics and treatment response of patients with primary peritoneal carcinoma. To improve survival of PPC, a further clinical study is needed to evaluate the use of further optimal debulking surgery and chemotherapy.

References

- 1.Swerdlow M. Mesothelioma of the pelvic peritoneum resembling papillary cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary; case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;77:197–200. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(59)90287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altaras MM, Aviram R, Cohen I, Cordoba M, Weiss E, Beyth Y. Primary peritoneal papillary serous adenocarcinoma: clinical and management aspects. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;40:230–236. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90283-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fromm GL, Gershenson DM, Silva EG. Papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lele SB, Piver MS, Matharu J, Tsukada Y. Peritoneal papillary carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1988;31:315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(88)80010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ransom DT, Patel SR, Keeney GL, Malkasian GD, Edmonson JH. Papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. A review of 33 cases treated with platin-based chemotherapy. Cancer. 1990;66:1091–1094. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900915)66:6<1091::aid-cncr2820660602>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloss JD, Liao SY, Buller RE, Manetta A, Berman ML, McMeekin S, et al. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: a case-control retrospective comparison to papillary adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50:347–351. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu CS, Menzin AW, Leonard DG, Rubin SC, Wheeler JE. Primary peritoneal carcinoma: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1999;54:323–335. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199905000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cormio G, Di Vagno G, Di Gesu G, Mastroianni M, Melilli GA, Vimercati A, et al. Primary peritoneal carcinoma: a report of twelve cases and a review of the literature. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000;50:203–206. doi: 10.1159/000010311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barda G, Menczer J, Chetrit A, Lubin F, Beck D, Piura B, et al. Comparison between primary peritoneal and epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1039–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatment G. World Health Organization; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills SE, Andersen WA, Fechner RE, Austin MB. Serous surface papillary carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and comparison with stage III-IV ovarian serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:827–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalrymple JC, Bannatyne P, Russell P, Solomon HJ, Tattersall MH, Atkinson K, et al. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Cancer. 1989;64:110–115. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890701)64:1<110::aid-cncr2820640120>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss NS, Homonchuk T, Young JL., Jr Incidence of the histologic types of ovarian cancer: the U.S. Third National Cancer Survey, 1969~1971. Gynecol Oncol. 1977;5:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(77)90020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taus P, Petru E, Gucer F, Pickel H, Lahousen M. Primary serous papillary carcinoma of the peritoneum: a report of 18 patients. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1997;18:171–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen KT, Flam MS. Peritoneal papillary serous carcinoma with long-term survival. Cancer. 1986;58:1371–1373. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860915)58:6<1371::aid-cncr2820580632>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bloss JD, Brady MF, Liao SY, Rocereto T, Partridge EE, Clarke-Pearson DL. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: a phase II trial of cisplatin and cyclophosphamide with comparison to a cohort with papillary serous ovarian carcinoma-a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skates S, Troiano R, Knapp RC. Longitudinal CA125 detection of sporadic papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:693–696. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.t01-1-13050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlan BY, Baldwin RL, Lopez-Luevanos E, Raffel LJ, Barbuto D, Narod S, et al. Peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma, a phenotypic variant of familial ovarian cancer: implications for ovarian cancer screening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:917–928. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Truong LD, Maccato ML, Awalt H, Cagle PT, Schwartz MR, Kaplan AL. Serous surface carcinoma of the peritoneum: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Human pathology. 1990;21:99–110. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90081-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubernard G, Morice P, Rey A, Camatte S, Fourchotte V, Thoury A, et al. Prognosis of stage III or IV primary peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:976–981. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowalski LD, Kanbour AI, Price FV, Finkelstein SD, Christopherson WA, Seski JC, et al. A case-matched molecular comparison of extraovarian versus primary ovarian adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:1587–1594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]