Abstract

Although experimental studies support that men generally respond more to visual sexual stimuli than do women, there is substantial variability in this effect. One potential source of variability is the type of stimuli used that may not be of equal interest to both men and women whose preferences may be dependent upon the activities and situations depicted. The current study investigated whether men and women had preferences for certain types of stimuli. We measured the subjective evaluations and viewing times of 15 men and 30 women (15 using hormonal contraception) to sexually explicit photos. Heterosexual participants viewed 216 pictures that were controlled for the sexual activity depicted, gaze of the female actor, and the proportion of the image that the genital region occupied. Men and women did not differ in their overall interest in the stimuli, indicated by equal subjective ratings and viewing times, although there were preferences for specific types of pictures. Pictures of the opposite sex receiving oral sex were rated as least sexually attractive by all participants and they looked longer at pictures showing the female actor’s body. Women rated pictures in which the female actor was looking indirectly at the camera as more attractive, while men did not discriminate by female gaze. Participants did not look as long at close-ups of genitals, and men and women on oral contraceptives rated genital images as less sexually attractive. Together, these data demonstrate sex-specific preferences for specific types of stimuli even when, across stimuli, overall interest was comparable.

Keywords: sexual stimuli, sex differences, viewing time, oral contraceptives

INTRODUCTION

Men are typically assumed to respond more to visual sexual stimuli than women. Studies asking participants to indicate how attractive and sexually arousing they find visual sexual stimuli generally report higher ratings from men than from women (Laan, Everaerd, van Bellen, & Hanewald, 1994; Money & Ehrhardt, 1972; Schmidt, 1975; Steinman, Wincze, Sakheim, Barlow, & Mavissakalian, 1981), although there is substantial variability in the effect size of this sex difference (Murnen & Stockton, 1997). This variability may be due, in part, to the use of uncontrolled and varied types of experimental sexual stimuli. It is unknown how the specific content of visual sexual stimuli contributes to males’ and females’ interest in sexual stimuli (Money & Ehrhardt, 1972; Rupp & Wallen, 2008). Understanding what specific content males and females find sexually attractive could have practical implications for future sex research that aims to use stimuli of equal interest to males and females, and also contribute to our understanding of determinants of sexual response patterns in general.

Although few studies have specifically examined what types of visual sexual stimuli most interest men and women, limited research suggests that there may be sex differences in content preferences for visual sexual stimuli (Money & Ehrhardt, 1972; Rupp & Wallen, 2008). The primary sex difference is whether the stimuli depict same or opposite-sex actors. Generally, heterosexual men subjectively rate stimuli depicting nude males or male-male sexual behavior as less sexually arousing or attractive than stimuli including women (Costa, Braun, & Birbaumer, 2003; Schmidt, 1975; Steinman et al., 1981). In contrast, women generally rate photos of both males and females comparably attractive or arousing (Costa et al., 2003; Schmidt, 1975; Steinman et al., 1981). Genital measurement to same and opposite-sex stimuli shows the same pattern for men and women with men showing highest genital responding to their preferred sex while women show comparable genital arousal independent of the sex of the actors (Chivers, Rieger, Latty, & Bailey, 2004).

Limited research suggests that in addition to the sex of the actors in the stimuli, the sexual activity depicted influences men’s and women’s preferences. For example, when asked to subjectively indicate their sexual arousal in response to erotic videos that were chosen by either a male or female experimenter, participants reported stimuli chosen by a member of their own sex as more sexually arousing (Janssen, Carpenter, & Graham, 2003; Laan et al., 1994). In the Laan et al. study, the main characteristic that differentiated the male-created and female-created films was the amount of foreplay and focus on intercourse, with the male-created film involving no foreplay while the female-created film had four of 11-minutes devoted to it. This finding suggests that the type of sexual activity depicted in the stimuli is important to males and females in their response to such stimuli. However, when the amount of foreplay, oral sex, and intercourse was balanced in male and female selected films in the Janssen et al. (2003) study, men and women still had different film preferences, suggesting that there may be other characteristics of the stimuli, in addition to the proportion of sexual behaviors depicted, that maximize men and women’s arousal.

Recent studies using eye tracking find sex differences in men and women’s attention to different components of sexually explicit pictures (Lykins, Meana, & Kambe, 2006; Lykins, Meana, & Strauss, 2008; Rupp & Wallen, 2007a), supporting the idea that men and women have different preferences for components of sexually explicit pictures. In the Rupp and Wallen (2007a) study, although men and women’s looking patterns were similar in that all participants looked most at the female body, female face, and genitals, men spent more time than did women looking at the female face, women not using hormonal contraceptives looked more at the genitals, and women using hormonal contraceptives looked more at the background and clothing (Rupp & Wallen, 2007a). Generally, eye-tracking studies find more same-sex viewing interest in women than men (Lykins et al., 2006, 2008; Rupp & Wallen, 2007a). However, despite differences in gaze patterns, there were no sex differences in subjective ratings of the stimuli (Lykins et al., 2006; Rupp & Wallen, 2007a). Because men and women did not differ in subjective ratings, but had different patterns of attention, it is possible that men and women have different cognitive processing strategies when viewing sexual stimuli, and the different strategies produce equal levels of arousal though the aspects of the images visualized were different. Different types of stimuli may provide men and women with variable opportunities to use their preferred viewing strategies and maximize their interest in and arousal to the stimuli. Although eye tracking studies further demonstrate that men and women may have different preferences for certain specific components of sexual stimuli, it is still unclear how these content preferences translate into the kinds of stimuli men and women may prefer.

In addition to eye-tracking studies demonstrating sex differences in attention to visual sexual stimuli, recent neuroimaging work also suggests that men and women’s brains may respond differently to visual sexual stimuli (reviewed in Rupp & Wallen, 2008) even in the absence of sex differences in subjective ratings (Hamann, Herman, Nolan, & Wallen, 2004). This further suggests that subjective ratings may not capture possible sex difference in initial interest in and cognitive processing of visual sexual stimuli. We do not yet know the exact relationship between neural activation, reflecting changes in cognitive processing, and subjective and conscious evaluations of sexual stimuli. Conscious subjective evaluation of stimuli is a complex process emerging from multiple cognitive components, which may differ between men and women or with context. Differences in hormones between men and women, and within women based on hormonal contraceptive use would be expected to be a relevant factor influencing the cognitive processing of sexual stimuli due to its influence on sexual interest and motivation for sexual stimuli in general. However, it is unknown whether individual factors, such as hormones, influence preferences or interest in specific types of stimuli.

The current study aimed to determine whether men and women have reliable preferences for certain stimuli. The literature to date on men and women’s preferences for visual sexual stimuli suggests that men and women’s interest in and arousal to visual sexual stimuli may be dependent upon the activities and situations depicted in the stimuli. It is possible that there is overlap, in addition to differences, in preferences that could be utilized in experimental situations to provide stimuli of equal interest to men and women that may allow for more accurate experimental manipulations. Previous sex difference studies may have used stimuli that contained content of more interest to one sex than the other and produced sex differences that were specific to a set of visual sexual stimuli and not generalizable to all visual sexual stimuli.

Accurately investigating men and women’s stimulus preferences requires an objective unit of measurement that is directly comparable across both sexes. Most prior studies used subjective reports of sexual arousal or attraction. Such subjective scales are affected by subject bias and inhibition, especially in female participants (Alexander & Fisher, 2003). An alternative method uses genital changes in men and women, but the methodology and physical changes, vasocongestion in women and erection in men, are not comparable between the sexes. In contrast, viewing time offers a direct quantitative assessment of interest in sexual stimuli that does not rely upon subjective reports or genital response. Viewing time has been found to be a potentially useful methodology for measurement of sexual interest, in many studies men were found to look longer at pictures that they reported as more attractive (Harris, Rice, Quinsey, & Chaplin, 1996; Laws & Gress, 2004; Quinsey, Ketsetzis, Earls, & Karamanoukian, 1996). Similarly, men and women were found to look longer at pornographic images that they rated as more highly arousing (Brown, 1979). Additionally, in men, higher testosterone is correlated with longer viewing times, suggesting that viewing time may be an indicator of sexual motivation (Rupp & Wallen, 2007b).

The current study used viewing time as an objective measure of interest in the visual stimuli. The use of this methodology with visual sexual stimuli was intended to produce more objective measurement of preferences for visual sexual stimuli across sexes overall and within sexes based on the content of the stimuli. The current study included stimuli that varied with the sexual activity depicted, gaze of the female actor, and the proportion of the image that the genital region occupied. These components were selected based on previous literature suggesting a sex difference in viewing strategies for men and women and discrimination between same and opposite-sex stimuli (reviewed in Rupp & Wallen, 2008). Participants were expected to look longer at pictures depicting sexual activities that they preferred. We expected that men would show a preference for pictures depicting other males receiving oral sex and in a dominant intercourse position and vice versa for females due to both sexes tendency to project themselves into scenarios (Janssen et al., 2003; Money & Ehrhardt, 1972). We also predicted that men would have more interest in close-up images of the genitals than would females due to decreased interest in contextual information (Rupp & Wallen 2007a). Due to the male-specific objectification strategy, we expected them to demonstrate more interest in pictures with direct gaze compared to indirect gaze since these photos may allow them to connect more with the female actor. In contrast, we expected female participants to show more interest in pictures with indirect gaze compared to direct gaze since in may facilitate their projection into the scenario.

Understanding differences in preferences for visual sexual stimuli could assist in the interpretation of previously reported subjective, behavioral, and neurological sex differences in response to sexual stimuli and guide the development of stimulus sets of equal interest to men and women for future studies.

METHOD

Participants

This study included 45 heterosexual participants (men, normal cycling [NC] women, and oral contraceptive [OC] using women) between the ages of 23–35 years of age. Forty-two of the participants completed all three sessions (N = 14 in each group). Participants were from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. Participants were recruited through e-mail lists from Atlanta, GA area graduate and professional schools. The recruitment e-mail included a contact phone number allowing interested parties to contact research personnel. Upon receipt of the phone call, the experimenter briefly described the study and specified that the participant would be asked to view sexually explicit pictures of couples engaged in oral sex and intercourse.

Measures

If the potential participant was still interested after hearing information about the study from the experimenter over the phone, the experimenter asked the potential participant to pick up and return an applicant packet that included a questionnaire asking about oral contraceptive use for women (yes/no), some selected questions from the Brief Index of Sexual Function (BISF, Taylor, Rosen, & Leiblum, 1994) regarding sexuality and experience with pornography in the past month and year, and the Sexual Permissiveness subscale of the Sexual Attitudes Scale by Hendrick and Hendrick (1987). The Sexual Attitudes Scale is a 20-item Likert scale questionnaire asking how much participants agree with certain statements related to how sexually liberal their attitudes are. Lower scores indicated more conservative sexual attitudes. The information provided by potential participants was used for screening purposes to select appropriate participants with heterosexual preference and some experience with pornography. All of the potential participants who returned completed packets were eligible for the study and contacted for participation.

Procedure

Stimuli

Stimuli were sexually explicit color photos of heterosexual couples engaged in oral sex or intercourse taken from public domain websites. We presented equal numbers of photos depicting the following heterosexual activities: oral sex to male (OSM), oral sex to female (OSF), female dominant intercourse facing male partner (FDFM), female dominant intercourse facing away from male partner (FDFA), male dominant intercourse from front of female partner (MDFF), and male dominant intercourse from behind female partner (MDFB). These six activities were chosen to sufficiently describe the activities commonly depicted on mainstream internet pornography websites, but allowing for distinction of the gender in the superior position which we theorized may be a relevant characteristic to men and women in their evaluations of sexual stimuli. Within each of these activity groupings, pictures were matched with a paired picture containing the same actors and behaviors but differing either by the level of genital focus or by the gaze direction of the female actor. Half of the pictures within each activity variable were matched based on the genital focus: one picture of the scene had a close up focus on the genitals and the other matched picture was a distant perspective of the same scene. The genitals shown in the close up focus were dependent upon the activity depicted, all of the pictures from the intercourse categories showed pictures of both male and female genitals with penetration, oral sex to male pictures showed only the male genitals, and oral sex to female pictures showed only female genitals. The other half of the pictures was matched to vary only with the gaze of the female actor. We found pictures in which the female gaze was directed directly at the camera and matched them with nearly identical pictures in which the gaze was averted from the camera. We did not systematically vary the gaze of the male actor in the stimuli because pictures in which the male actor had a direct gaze at the viewer were difficult to find, in contrast to those including direct gaze of the female actor. Based on the sex difference in the use of an objectification strategy, we also thought it more important to focus on the gaze of the female actor, rather than the male, from a theoretical perspective.

A total of 364 pictures were chosen and downloaded from free sites on the Internet with the desired distribution across categories of sexual activity, genital focus, and female actor gaze. Before the eye tracking sessions began, these photos were independently rated by seven males and seven females not involved in the study for levels of sexual attractiveness. Pilot participants were instructed that a score of −1 indicated that the picture was sexually unattractive or in some way aversive and should not be included in the study. A score of zero meant that the picture was neutral; neither sexually attractive nor unattractive. A score of 1-4 indicated a positive reaction to the picture, 1 being the lowest, and 4 the highest rating of sexual attractiveness. Based on these pilot ratings, stimuli with a rating < 0 from any volunteer, were eliminated from the stimulus set. The remaining 322 pictures were ranked by mean rating and the 216 pictures with the highest mean ratings from both males and females within each activity were retained for the current study.

The final stimulus set consisted of 216 pictures. Since there were three sessions for each subject, three sets of stimuli (72 pictures each) were constructed with equally represented content (sexual activity, gaze, genital focus) and with statistically equal levels of sexual attractiveness, based on pilot ratings. This produced a total, for each session, of 18 pairs of pictures that varied according to gaze and 18 pairs that varied with genital focus. Within each of the 18 pairs, three pairs each portrayed the following activities, oral sex to a male by female, oral sex to a female by male, sexual intercourse with female dominant facing the male, sexual intercourse with female dominant facing away from the male, male dominant sexual intercourse facing towards the female, and male dominant intercourse facing away from the partner. This photo stimulus set with attractiveness ratings is available upon request for research use.

Testing

After the initial screening based on questionnaire results, participants came in for three test sessions during which they viewed visual sexual stimuli while their viewing time was recorded using Gazetracker software (Eye Response Technologies, Charlottesville, VA). Participants were seated comfortably in front of a laptop computer screen on which they were presented the stimuli. They were told that they could stop at any time and to let the experimenter know if they were uncomfortable at any point. Participants were instructed to look at the sexual image as long as they liked and to end viewing of the slide by pressing the space bar on the keyboard. Participants viewed a total of 72 pictures during each of three sessions including three pairs within each sexual activity from each stimulus category (gaze, genital focus, or activity). Participants viewed the same stimuli as each other during each of the three sessions. The photo presentation was randomized uniquely for each participant within each session so that no subject saw the same order of stimulus presentation as another subject within each session. A one second black screen with fixation crosshairs in the center preceded each photo to assure that the subject began the viewing of each photo from the same starting point. Viewing occurred privately with the experimenter separated from the testing area by a curtain. The experimenter could not see the participant or what they were looking at throughout testing.

Once the participant had viewed all 72 photos, a tone indicated to the experimenter that testing was complete. At this time, the curtain was opened and the session data were saved. Immediately following the viewing time paradigm, participants viewed all stimuli a second time in a different order and rated them on a nine point scale of sexual attractiveness on the computer keypad (1 = extremely sexually unattractive to 9 = extremely sexually attractive). Once they had completed ratings of all 72 photos, as indicated to the experimenter on the other side of the curtain by a tone, testing was complete. Participants were then compensated for their time and scheduled for their next session.

Data Analysis

Initial processing of viewing data used the same Gazetracker software that was used for stimulus presentation. Viewing time data from Gazetracker for each slide were exported into Microsoft Excel. The data were then transferred to SPSS for Windows (Version 13.0, SPSS Inc.) for statistical analyses.

The analyses investigated interest in the visual sexual stimuli. The dependent variables were viewing time and subjective ratings of sexual attractiveness. We conducted three different analyses in order to evaluate the effects of activity, gaze, and genital focus. The first was a mixed model 3 (Group: men, NCW, OCW) × 6 (Activity: OSM, OSF, FDFM, FDFA, MDFF, MDFB) repeated measures ANOVA. We also conducted a 3 (Group: men, NCW, OCW) × 2 (Gaze: direct, indirect) repeated measures ANOVA for gaze and a 3 (Group: men, NCW, OCW) × 2 (Genital Focus: close-in, far away) repeated measures ANOVA for genital focus. For all analyses, participants’ mean viewing times and subjective ratings of sexual attractiveness were the dependent measures. These analyses treated the mean viewing time and subjective rating of each participant for each activity type or category collapsed across all three test sessions as a data point. Main effects, interaction effects, and post-hoc analyses significant are reported. Finally, to look for relationships between participants’ viewing times and subjective ratings, we performed Pearson two-tailed correlations on these dependent measures overall and within each group.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows participants’ scores on questions regarding their sexual attitudes and previous viewing experience of explicit sexual material. Men and women did not differ in their sexual attitudes (M ± SD = 50.36 ± 14.00); however, men had more viewing experience with sexually explicit material, F(2, 43) = 9.16, p = .001, than both NC women (p < .001) and OC women (p = .001).

TABLE I.

Means and SEM on the Sexual Permissiveness Scale and Previous Viewing Experience as a function of group.

| Measure | M ± SEM |

|---|---|

| Sexual Attitudesa | |

| Men | 52.60 ± 4.36 |

| NC Women | 50.53 ± 3.56 |

| OC Women | 47.79 ± 2.96 |

| Viewing Experienceb | |

| Men | 3.23 ± 0.30 |

| NC Women | 1.83 ± 0.23 |

| OC Women | 1.93 ± 0.24 |

Absolute range, 20–100.

Absolute range, 0–6.

Across all participants, sexual attitudes, r(44) = .47, p < .003, and viewing experience, r(44) = .39, p = .01, positively predicted subjective ratings, but not viewing time. Correlations within groups, however, demonstrated sex-specific influences of participants’ sexual attitudes and viewing experience. For men, sexual attitudes were related to their subjective ratings, r(14) = .55, p = .05, but not viewing time. In contrast, sexual attitudes positively predicted NC women’s viewing time, r(14) = .62, p = .01, but had no effect on their subjective ratings. Within OC women, we did not find any significant correlations with their sexual attitudes as observed overall and within the other two groups, but there was a correlation between OC Women’s subjective ratings and their previous viewing experience, r (14) = .79, p = .001.

Viewing Time

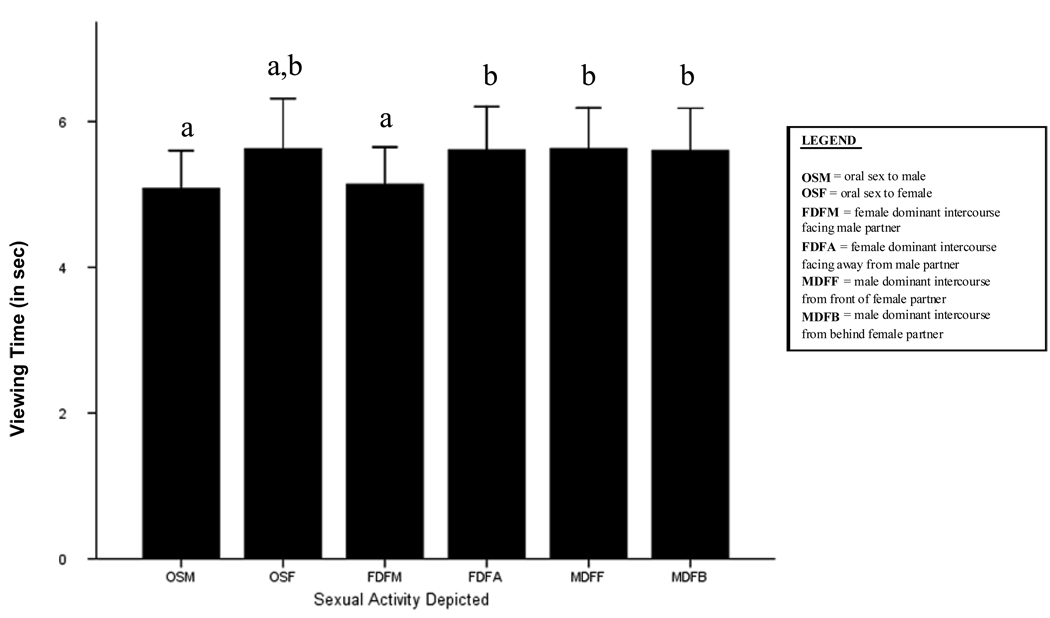

Table 2 shows mean viewing times as a function of group and sexual activity. A 3 (Group) × 6 (Sexual Activity) repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a main effect of sexual activity on participants’ viewing times, F(5, 185) = 3.43, p = .006, Figure 1.

TABLE II.

Means and SEM for interest measures by type of sexual activity and sex.

| Viewing Time (Seconds) | Subjective Ratinga | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SEM | M ± SEM | ||

| Oral Sex to Male | |||

| Men | 5.10 ± 2.53 | 6.39 ± 1.09b | |

| NCW | 4.80 ± 3.94 | 5.64 ± 0.98c | |

| OCW | 5.37 ± 3.37 | 5.34 ± 1.06c | |

| Male Dominant Facing Female | |||

| Men | 5.28 ± 2.26 | 6.24 ± 0.84 | |

| NCW | 5.19 ± 3.95 | 6.22 ± 0.70 | |

| OCW | 6.45 ± 4.16 | 6.03 ± 0.83 | |

| Female Dominant Intercourse Facing Away from Male | |||

| Men | 5.24 ± 2.37 | 6.21 ± 0.87 | |

| NCW | 5.35 ± 4.31 | 6.10 ± 0.75 | |

| OCW | 6.26 ± 4.34 | 5.80 ± 0.89 | |

| Female Dominant Intercourse Facing Male | |||

| Men | 4.98 ± 2.35 | 6.07 ± 0.92 | |

| NCW | 4.50 ± 3.17 | 6.09 ± 0.79 | |

| OCW | 6.00 ± 4.00 | 5.53 ± 1.09 | |

| Male Dominant Facing Away from Female | |||

| Men | 5.20 ± 2.45 | 6.00 ± 0.87 | |

| NCW | 5.38 ± 4.52 | 6.13 ± 0.79 | |

| OCW | 6.24 ± 3.91 | 5.71 ± 0.90 | |

| Oral Sex to Female | |||

| Men | 4.94 ± 2.29 | 5.75 ± 0.93c | |

| NCW | 5.75 ± 6.25 | 5.98 ± 1.44 | |

| OCW | 6.18 ± 3.66 | 5.99 ± 1.37 | |

Absolute range, 1–9.

Denotes a significant difference between men and both groups of women within activity type.

Denotes a significant difference within group between the activity type and all other activity types.

Figure 1.

Viewing time (M ± SEM) by activity overall groups. Viewing of OSM and FDFM was shorter than FDFA and MD pictures (all ps <.01). Significant differences are indicated by different letters.

Post hoc paired contrasts showed that, overall, participants did not look as long at pictures depicting oral sex to men as they did when looking at pictures depicting FDFA (p = .002), MDFF (p = .001), or MDFB (p = .002) pictures. Pictures in which the female actor was dominant and facing towards her male partner (FDFM) were viewed for shorter times than were pictures of intercourse in which the female actor was facing away from her partner (FDFA, p = .005) or in which the male actor was dominant (MDFF, p < .001; MDFB, p = .009).

Table 3 shows mean viewing times as a function of group, gaze of the female actor, and level of genital focus. A 3 (Group) × 2 (Gaze) repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated no effect of group or gaze on participants’ viewing times. Finally, a 3 (Group) × 2 (Genital Focus) repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a main effect of genital focus on participants’ viewing times, F(1, 39) = 39.63, p < .001. All participants looked longer at pictures with a farther genital focus compared to those with a close-in focus (within sex paired samples t-test; men, t = 3.77, p = .002; NCW, t = 2.83, p = .01; OCW, t = 4.28, p = .001).

TABLE III.

Mean and SEM for interest measures by picture category and sex.

| Direct Gaze | Indirect Gaze | Genital Close | Genital Far | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SEM | M ± SEM | M ± SEM | M ± SEM | |

| Viewing Time (seconds) | ||||

| Men | 4.99 ± 2.49 | 5.00 ± 2.61 | 4.37 ± 2.19b | 5.35 ± 2.55 |

| NCW | 5.14 ± 4.25 | 5.18 ± 4.29 | 4.94 ± 4.43b | 5.74 ± 5.12 |

| OCW | 5.99 ± 3.86 | 6.45 ± 3.90 | 5.26 ± 3.30b | 6.99 ± 4.18 |

| Overall | 5.37 ± 3.55 | 5.55 ± 3.64 | 4.86 ± 3.37b | 6.02 ± 4.05 |

| Subjective Ratings (1-9) | ||||

| Men | 6.44 ± 0.93a | 6.47 ± 0.76 | 5.21 ± 1.40b | 6.52 ± 0.75 |

| NCW | 5.88 ± 0.81b | 6.19 ± 0.75 | 5.88 ± 1.00c | 6.18 ± 0.78 |

| OCW | 5.83 ± 0.76b | 6.29 ± 0.65 | 4.82 ± 1.56b | 6.14 ± 0.78 |

| Overall | 6.05 ± 0.86b | 6.31 ± 0.72 | 5.30 ± 1.38b | 6.28 ± 0.77 |

Denotes a significant difference between men and both groups of women within category.

Denotes a significant within group difference between categories (direct versus indirect; close versus far).

Denotes a significant difference between NC women and OC women.

Subjective Ratings

Table 2 shows participants’ subjective ratings by group and sexual activity. A 3 (Group) × 6 (Sexual Activity) repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a sex by activity interaction, F(10, 185) = 2.11, p = .03, showing sex-specific preferences for certain stimuli. One-way ANOVA post-hoc analyses within each activity category demonstrated that men rated pictures of the male actor receiving oral sex as more sexually attractive than did both groups of women, F(2, 40) = 3.43, p = .04 (vs. NCW, p = .07; vs. OCW, p = .02). Further, post hoc analyses within each sex revealed that men’s ratings were dependent upon the activity depicted (Greenhouse Geisser correction, F(1.96, 23.56) = 3.46, p = .05, partial eta- squared = .22). Paired contrasts revealed lower ratings within men for pictures depicting oral sex to females, which were rated significantly lower than all other pictures except for pictures in the MDFB category (OSF vs. OSM, p = .05; vs. FDFM, p = .03; vs. FDFA, p = .03; vs. MDFF, p = .004). NC and OC women, in contrast, did not demonstrate a difference in subjective ratings based on the activity depicted.

Table 3 shows participants’ subjective ratings by group and the gaze of the female actor. A 3 (Group) × 2 (gaze) repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a main effect of gaze F(1, 39) = 14.44, p < .001, and an interaction of gaze with group, F(2, 39) = 3.21, p = .05, on participants’ subjective ratings. Overall, participants rated pictures with an indirect female gaze to be more sexually attractive. However, post hoc analyses (paired t-tests within each sex) of the sex by gaze interaction also demonstrated that although both groups of women rated the picture of indirect gaze as more sexually attractive than direct gaze pictures (NCW, t = 2.64, p = .02; OCW, t = 2.90, p = .01), men did not discriminate. Further post hoc analyses within gaze category across sexes showed a trend in which men rated pictures in which the female actor was looking directly at them as more sexually attractive than did either group of women (vs. NCW, p = .06; vs. OCW, p = .08).

Table 3 shows participants’ subjective ratings by group and the genital focus. A 3 (Group) × 2 (genital focus) repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated a main effect of genital focus, F(1, 39) =37.97, p < .001, and a group by genital focus interaction, F(2, 39) = 4.58, p = .02, on participants’ subjective ratings. Overall, participants rated pictures depicting a close-up focus to be less attractive. However, within-sex post hoc analyses demonstrated that NC women did not significantly rate photos differently based on their level of genital focus, while OC women and men did (OCW, t = 4.17, p = .001; men, t = 4.17, p = .001). Post hoc analyses within genital focus category across sexes showed that NC women rated pictures depicting a close-up genital focus as more sexually attractive than did OC women (p = .04) although their was no difference between men’s ratings and either group of women’s related to the genital focus.

Correlations Between Viewing Time and Subjective Ratings

Across all participants, there was not a significant correlation between participants’ viewing times and subjective ratings. However, correlations within groups by activity showed significant correlations for both OC and NC women that were specific to the activity depicted. Specifically, within NC women their viewing times and subjective ratings were significantly associated only for pictures depicting oral sex to a female, r(14) = .56, p = .04. OC women’s viewing time and subjective ratings were significantly correlated for pictures depicting the male actor receiving oral sex, r(14) = .52, p = .05, for MDFF pictures, r(14) = .55, p = .05, and for genital close-up pictures, r(14) = .54, p = .05. For men, viewing times and subjective ratings were not significantly correlated for any of the pictures.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to investigate sex differences in preferences for visual sexual stimuli, measured using both subjective ratings and an implicit measure of interest, participants’ viewing time. We did not find a significant difference between men and women in their overall subjective ratings or viewing times of the stimuli, inconsistent with the commonly held assumption that men find visual sexual stimuli more interesting and arousing than do women. Preferences for specific types of pictures varied by group. Specifically, men and women rated pictures of the opposite sex receiving oral sex as least sexually attractive. Participants also looked longer at intercourse shots in which they could more clearly see the female actor’s body, including the FDFA, MDFF, and MDFB pictures. Unlike subjective ratings, stimulus preferences for certain activities measured by viewing times did not vary significantly by group. Women rated pictures with an indirect female gaze more attractive, although men did not discriminate based on the gaze of the female actor. Participants did not look as long at close-up genital images, and men and OC women rated them less sexually attractive than pictures less focused on the genitals. Subjective ratings and viewing times were correlated only in women for pictures that held the strongest attraction or aversion, specifically those depicting oral sex to males or females and close-up genital views. Together, these data demonstrate sex-specific preferences for certain types of stimuli even when overall interest across stimuli was equal.

Men and women’s preferences observed here were consistent with previous literature suggesting different viewing strategies for men and women (Janssen et al., 2003; Money & Ehrhardt, 1972). The preferences for same-sex oral sex stimuli were consistent with previous literature in which women use projection strategies when viewing sexual stimuli, while men use both objectification and projection strategies. This could explain why both men and women had subjective preferences for pictures in which a member of their own sex was receiving, but not giving, oral sex. Men, however, also used an objectification strategy when viewing visual sexual stimuli, in which they imagined themselves engaged in sexual activity with the female actor. That women are thought to project themselves into sexual scenarios, rather than objectify the actor, could contribute to their observed preference for stimuli in which the female actor gazed indirectly. A direct gaze may give more presence or identity to the female actor, making it more difficult for the women to imagine that it is them in the sexual scenario, and not the female actor. Men, who are thought to use both objectification and projection strategies, did not discriminate based on the gaze of the female actor. Additionally, it is also possible that because women had less previous viewing experience of visual sexual stimuli they did not want to be “seen” looking at pornography by the woman in the photo.

Another well-known sex difference possibly contributing to the findings of the current study is that women do not demonstrate the same category-specific response to sexual stimuli as do men (Chivers et al., 2004; Chivers, Seto, & Blanchard, 2007). Specifically, heterosexual women will respond sexually to stimuli of their non-preferred sex, while men will not (Chivers et al., 2004, 2007). In the current study, both men and women looked longer at pictures of intercourse when the female actor was facing away from her partner or the male actor was dominant. As a consequence of the activity depicted, differing amounts of the female actor’s body was visible. In pictures in which the female actor was dominant and facing her partner, little could be seen of her body other than her back. However, in the other pictures of intercourse, the female actor’s body was more accessible for viewing, possibly explaining why both men and women looked longer at them. This is consistent with recent eye tracking studies demonstrating that men and women looked equally as long, and as often, at the female actors’ body when viewing visual sexual stimuli (Lykins et al., 2008; Rupp & Wallen, 2007a) and consistent with a non target-specific pattern of arousal in women, but not men (Chivers et al., 2004, 2007).

The other salient characteristic to men and women was the degree to which genitals dominated the image. All participants spent less time looking at pictures featuring a close-up genital view. This could be interpreted that they either did not like such pictures as much or that these were less complex pictures and had less potential information to process. Because men and OC women rated the close-up pictures as less sexually attractive, we would argue that the viewing times reflected less absolute interest. NC women, however, did not show the decreased subjective attraction to these pictures as did the other groups. This is also consistent with eye-tracking data in which women not using hormonal contraceptives looked more at the genitals in the photos compared to men or to women using hormonal contraceptives (Rupp & Wallen, 2007a). Whether these differences between women are due to the hormone differences produced by oral contraceptive use (Carlstrom, Lunell, & Zador, 1978) or reflect the different psychosocial variables contributing to a woman’s decision to use oral contraception (Bancroft, Sherwin, Alexander, Davidson, & Walker, 1991) remains unclear from the current study. Differences between the OC and NC women in this study were likely due to differences in both the hormone profiles and psychosexual traits of women who do and do not use hormonal contraceptives (Bancroft et al., 1991; Graham et al., 2007). Absolute hormone levels, specifically testosterone, and personal factors such as sexual motivation, have been shown to predict men’s viewing time of visual sexual stimuli (Rupp & Wallen, 2007b), and may influence women’s viewing time as well.

That men and women demonstrated sex-specific preferences for certain stimuli in the absence of overall sex differences in subjective ratings or viewing times warrants further discussion. This highlights the influence that the stimuli used can have on studies examining sex differences in subjective ratings of sexual stimuli. The design of the current study produced balanced numbers of pictures depicting oral sex to men and women and intercourse from a variety of viewpoints. The assortment of stimuli may have allowed men and women a greater opportunity to utilize their preferred viewing strategies and maximized their interest in the stimuli. The stimuli were also pilot-tested to ensure that they were attractive to women. In order to acquire a balanced picture set for pilot testing and the test sessions, the experimenters had to create their own stimulus set from pictures found on public domain websites on the Internet. The only currently available picture set including visual sexual stimuli, to the authors’ knowledge, is the International Affective Picture System (IAPS, Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2005). We did not use pictures from this set due to the large number of stimuli needed, and the desired sexual activity distribution. Additionally, we felt that a more updated picture set would be more appropriate for the relatively young sample of participants. However, because we used our own stimulus set instead of the IAPS, our stimuli are not validated beyond our limited pilot testing or controlled for many important variables, such as valence or arousal. We highlight the need for the production of a validated and extensive set of visual sexual stimuli for future research.

It is unclear whether sex-specific preferences would translate from our laboratory setting to naturalistic sexual encounters, or to a different population, due to the explicit nature of the visual stimuli used. It is difficult to extrapolate these findings regarding men and women’s preferences for sexually explicit visual scenes to predictions of their real world sexual arousal patterns and evaluations. The current study used explicit sexual pictures for the dual practical purposes of assisting in the development of a stimulus set that is of interest to both men and women, and to maximize men and women’s sexual interest to test for potentially subtle differences in preferences. Due to the nature of the stimuli used, which the participants were informed about before consenting to the study, we may have tested a unique group of study participants. As with most research studies investigating questions about sex, our study may be confounded by a biased self-selected sample that is more sexually liberal and comfortable with sexuality than the average population. Scores on women’s sexual attitudes were generally higher than those reported in the general population, although women’s previous viewing experience was relatively low and probably more similar to the general population. Future work may build upon the current study that has established sex differences in visual stimulus preferences and use visual stimuli that are more relevant to men and women’s real world sexual decision-making and social evaluations, which may also attract a more representative study sample.

The final point that we would like to discuss is the relationship between this relatively new methodology, viewing time, and subjective ratings. Of note, we found sex differences in activity preferences only for subjective ratings, but not viewing times, even though viewing times differed by activity for participants overall. It is possible, therefore, that men and women’s initial interest in visual sexual stimuli does not differ, but, rather, it is their interpretation and conscious evaluation of the stimuli that diverges which is reflected in their subjective reports. The lack of an overall correlation between subjective ratings and viewing times in the current study was consistent with a null correlation reported in a recent study (Israel & Strassberg, 2008). The current data did, however, show a correlation between viewing time and subjective ratings that was content and sex dependent. Both groups of women had significantly correlated subjective ratings and viewing times for specific types of visual stimuli. We do not interpret the lack of consistent correlations between subjective ratings and viewing times to be evidence that viewing time is an “invalid” measurement of sexual interest. Instead, we see this to be evidence that viewing time measures a different aspect of the response to sexual stimuli than does subjective reporting, which is precisely what it is intended to do.

Viewing time is a measure of interest in stimuli that is unfiltered through conscious subjective processing. In some cases in which initial cognitive interest is not in conflict with the psychosocial mediators of subjective ratings, such as sexual attitudes or previous viewing experience, the two may be very highly correlated. However, in cases in which there is a conflict between an individual’s conscious idea of what they find sexually arousing based on their own sexual schema, for example, and their objective interest in a visual sexual stimulus, the two measures may not be correlated due to the cognitive dissonance. That OC women and NC women showed correlations between viewing time and subjective ratings for the two types of activities that they had the least (OSM, close-up genital views) and most (OSF) interest in, respectively, supports this interpretation. In the investigation of sex differences, therefore, it is important to recognize the stage of processing and evaluation that may be captured with different methodologies, including the measurement of genital blood flow, questionnaires, neuroimaging, and viewing time.

In summary, the content of sexual stimuli influences men and women’s interest in visual sexual stimuli. Whether the observed sex differences in ratings of visual sexual stimuli are the product of biologically driven differences in sexual motivation, socialized sexual attitudes, and comfort with visual sexual stimuli, or the combination of these, remains unknown. However, these differences and similarities are of practical significance for future sex research that aims to use experimental stimuli of equal interest to men and women. Theoretically, this study’s combination of subjective and implicit measurement demonstrating limited and stimulus-specific correlations between the two also emphasizes the complex and multi-step process of men and women’s response to visual sexual stimuli. We would argue that the presence or absence of sex differences in preferences and response to sexual stimuli depend on the stimuli, level, and method of measurement, and should be considered in the interpretation of data suggesting sex differences in response to visual sexual stimuli.

REFERENCES

- Alexander MG, Fisher TD. Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self-reported sexuality. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:27–35. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft J, Sherwin BB, Alexander G, Davidson DW, Walker A. Oral contraceptives, androgens, and the sexuality of young women: A comparison of sexual experience, sexual attitudes, and gender role in oral contraceptive users and nonusers. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1991;20:105–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01541938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. Viewing time of pornography. Journal of Psychology. 1979;102:83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Carlstrom K, Lunell NO, Zador G. Serum levels of FSH, LH, estradiol-17 beta, and progesterone following the administration of a combined oral contraception containing 20 micrograms ethinylestradiol. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 1978;9:304–311. doi: 10.1159/000300999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers ML, Rieger G, Latty E, Bailey JM. A sex difference in the specificity of arousal. Psychological Science. 2004;15:736–744. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers ML, Seto MC, Blanchard R. Gender and sexual orientation differences in sexual response to sexual activities versus gender of actors in sexual films. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:1108–1121. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Braun C, Birbaumer N. Gender differences in response to pictures of nudes: A magnetoencephalographic study. Biological Psychology. 2003;63:129–147. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(03)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham CA, Bancroft J, Doll HA, Greco T, Tanner A. Does oral contraceptive-induced reduction in free testosterone adversely affect the sexuality or mood of women? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:246–245. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S, Herman RA, Nolan CL, Wallen K. Men and women differ in amygdala response to visual sexual stimuli. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:1–6. doi: 10.1038/nn1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GT, Rice ME, Quinsey VL, Chaplin TC. Viewing time as a measure of sexual interest among child molesters and normal heterosexual men. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:389–394. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick S, Hendrick C. Multidimensionality of sexual attitudes. Journal of Sex Research. 1987;23:502–526. [Google Scholar]

- Israel E, Strassberg DS. Viewing time as an objective measure of sexual interest in heterosexual men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen E, Carpenter D, Graham CA. Selecting films for sex research: Gender differences in erotic film preferences. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32:243–251. doi: 10.1023/a:1023413617648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laan E, Everaerd W, van Bellen G, Hanewald G. Women’s sexual and emotional responses to male- and female-produced erotica. Archives of Sexual Behaviour. 1994;23:153–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01542096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Instruction manual and affective ratings (Tech. Rep. No. A-6) Gainesville: University of Florida; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Laws DR, Gress CLZ. Seeing things differently: The viewing time alternative to penile plethysmography. Law and Criminal Psychology. 2004;9:183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lykins AD, Meana M, Kambe G. Detection of differential viewing patterns to erotic and non-erotic stimuli using eye-tracking methodology. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:569–575. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9065-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykins AD, Meana M, Strauss GP. Sex differences in visual attention to erotic and non-erotic stimuli. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:219–228. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Money J, Ehrhardt AA. Man and woman boy and girl: The differentiation and dimorphism of gender identity from conception to maturity. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Murnen SK, Stockton M. Gender and self-reported arousal in response to sexual stimuli: A meta-analytic review. Sex Roles. 1997;37:135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Quinsey VL, Ketsetzis M, Earls C, Karamanoukian A. Viewing time as a measure of sexual interest. Ethology and Sociobiology. 1996;17:341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp HA, Wallen K. Sex differences in viewing sexual stimuli: An eye-tracking study in men and women. Hormones and Behavior. 2007a;51:524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp HA, Wallen K. Relationship between testosterone and interest in sexual stimuli: The effect of experience. Hormones and Behavior. 2007b;52:581–589. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp HA, Wallen K. Sex differences in response to visual sexual stimuli: A review. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:206–218. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9217-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt G. Male-female differences in sexual arousal and behavior during and after exposure to sexually explicit stimuli. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1975;4:353–365. doi: 10.1007/BF01541721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman DL, Wincze JP, Sakheim, Barlow DH, Mavissakalian M. A comparison of male and female patterns of sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1981;10:529–547. doi: 10.1007/BF01541588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JF, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Self-report assessment of female sexual function: Psychometric evaluation of the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1994;23:627–643. doi: 10.1007/BF01541816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]