Abstract

Triglycerides (TG) stored in lipid droplets (LDs) are the main energy reserve in all animals. The mechanism by which animals mobilize TG is complex and not fully understood. Several proteins surrounding the LDs have been implicated in TG homeostasis such as mammalian perilipin A and insect lipid storage proteins (Lsd). Most of the knowledge on LD-associated proteins comes from studies using cells or LDs leaving biochemical properties of these proteins uncharacterized. Here we describe the purification of recombinant Lsd1 and its reconstitution with lipids to form lipoprotein complexes suitable for functional and structural studies. Lsd1 in the lipid bound state is a predominately α-helical protein. Using lipoprotein complexes containing triolein it is shown that PKA mediated phosphorylation of Lsd1 promoted a 1.7-fold activation of the main fat body lipase demonstrating the direct link between Lsd1 phosphorylation and activation of lipolysis. Serine 20 was identified as the Lsd1-phosphorylation site triggering this effect.

Keywords: Lsd, lipolysis, lipid droplets, PAT-protein, TG-lipase, TGL, phosphorylation, PKA, fat body, AKH

INTRODUCTION

Neutral lipids in the form of triglycerides (TG) are the predominant form of storage of fatty acids and comprise the main energy reserve in all animals [1]. The ability to store and release this energy involves a carefully regulated balance between TG synthesis and hydrolysis. Energy metabolism and its regulation are key processes defining insect survival and reproduction. Insects accumulate TG as lipid droplets (LDs) within the cytoplasm of fat body cells during feeding periods, and rely on these reserves during physiological non-feeding periods, sustained flight and embryo development [2, 3].

LDs play an active role in the release of stored fatty acids [4]. The lipid droplet surface, composed by phospholipids and proteins, represents a barrier for the hydrolysis of TG, which resides in the core of the particle [4, 5]. However, in the presence of the proper stimuli changes on the surface of the lipid droplet ensure a rapid hydrolysis of TG. Insect LDs contain many proteins [6, 7] including two PAT proteins. The PAT family was defined on the basis of sequence similarities among three vertebrate LD proteins: Perilipin, ADRP, and TIP47 [8]. These proteins are associated with intracellular lipid droplets, but TIP47 is also found in the cytosol [9]. PAT proteins are expected to play important roles in the deposition and utilization of TG [10, 11]. The PAT domain is an N-terminal sequence of ~100 residues [8]. Since the PAT domain is not required for targeting perilipin and ADRP to the LDs its role remains uncertain [12, 13]. Perilipin is the best characterized LD protein so far. Perilipin functions as a critical regulator of TG lipolysis in vertebrate adipocytes [4, 14] preventing or stimulating TG hydrolysis depending on its degree of phosphorylation [15]. Insect genomes encode only two PAT proteins, Lsd1 and Lsd2, which localize in the LDs [9, 16]. The overall sequence similarity of Lsd with the vertebrate family members is very low. Lsd2 is required for proper deposition of TG [17–19], while Lsd1 is involved in the activation of TG lipolysis [6].

Adipokinetic hormone (AKH), the main lipolytic hormone of insects [20], promotes a rapid phosphorylation and activation of the lipid droplets [6]. Changes in the lipid droplets accounted for ~70 % of the lipolytic response [21]. AKH stimulates lipolysis by a cAMP and Ca+2 dependent mechanism mediated by PKA activation [20, 22]. Previous studies identified Lsd1 as the main target of PKA [6]. Given its phosphorylation by PKA, Lsd1 most closely resembles perilipin A in terms of function [6]. The mechanism by which Lsd1 phosphorylation, alone or in conjunction with other lipid droplet proteins, activates lipolysis in insects is unknown.

Since LDs are complex organelles that contain a large number of proteins, the study of the mechanism of lipolysis would be facilitated if one would have an in vitro system that use purified proteins. Here we show the purification of recombinant Lsd1 and its assembly in lipoproteins complexes. Using this system we were able to study some structural features of Lsd1 as well as the effect of Lsd1 phosphorylation on the activity of the main fat body TG-lipase (TGL) in vitro. PKA mediated phosphorylation of Lsd1 promoted a significant activation of TGL demonstrating a direct role of Lsd1 in the control of lipolysis in insects. This is the first study showing the feasibility of reconstituting a lipid droplet protein in a lipoprotein system useful for structural and functional studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Total mRNA from Drosophila melanogaster was purchased from Invitrogen. pIEx-1 Ek/LIC vector, E. coli Rosetta 2, DNAse I, anti-His and anti S-tag antibodies were obtained from Novagen. [γ-32P]-ATP was purchased from MP Biochemicals. [tri-9,10-3H(N)]oleoylglycerol was purchased from Perkin Elmer. DMPG (dimyristoyl phosphatidylglycerol) was purchased from Serdary. Catalytic subunit of protein kinase A was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. DNA sequencing was performed by departmental Core Facility using ABI Model 3700 DNA Analyzer. All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Expression and purification of recombinant Lsd1

Total mRNA was reverse transcribed using oligo-d(T)18-primer and the cDNA was used to amplify the coding region of Lsd1 (CG10374, NP_732904.2) by PCR. The left and right primers were 5′-GACGACGACAAGATGGCAACTGCAACCAGCGGCAGTGGA and 5′-GAGGAGAAGCCCGGTCTAGACGCCGTTGATGTTATTGTG. The product was ligated into the vector pET-32 Ek/LIC that contains an N-terminal coding sequence for thioredoxin followed by His-Tag and S-Tag coding sequences. E. coli strain NovaBlue GigaSingles cells were transformed with the recombinant plasmid. Positive clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing. E. coli Rosetta 2 cells were transformed for protein expression. Expression of the recombinant protein was induced with 1mM IPTG in 1 liter of suspension culture. After 2 h, bacteria were collected and resuspended in buffer (50mM Tris pH8, 1mM EDTA, 100mM NaCl, 1mM PMSF) containing 0.3 mg/ml of lysozyme. After 30 min incubation, the preparation was centrifuged at 100,000g for 1h. The fusion protein was found in the pellet, which was resuspended in 0.1M sodium acetate pH5, 5mM MgCl2 and incubated with DNAse I at 37 °C for 1h. Sample was centrifuged (35,000g, 20min) and the pellet was resuspended in 20mM Tris pH7.5, 6M urea, 0.3 % octylglucoside, 0.5M NaCl and vortexed at 40°C for 15min. After centrifugation (5000g, 20 min) the procedure was repeated twice. The final pellet was resuspended in 20mM Tris pH11, 8M urea, 1 % cholate, 0.5M NaCl, 1mM DTT and sonicated in two steps for 1min each time. The preparation was centrifuged (5000g, 20 min) and the pH adjusted to 7.5. Trx-Lsd1 stock solution (5mg/ml) was kept in the freezer. Before usage the preparation was diluted to 0.5 mg/ml and dialyzed to a final concentration of 20 mM Tris pH7.5, 2M urea, 0.10M NaCl, 0.01% cholate.

Reconstitution of Trx-Lsd1 in lipoprotein particles and thrombin cleavage

DMPG liposomes (6mg/ml) in 20mM Tris pH7.5, 2M urea, 0.10M NaCl, were prepared by adding 0.2 ml of buffer into a glass vial containing a thin film of DMPG (1.2 mg). The vial was vortexed vigorously for 30s at RT. DMPG liposomes (400 nmol) were mixed with 8 nmoles of fusion protein (Trx-Lsd1) in 20 mM Tris pH7.5, 2M urea, 0.10M NaCl, 0.01% cholate. The final molar ratio of cholate to DMPG was 2. The samples were exhaustively dialyzed for 24 h against phosphate buffer (5mM PO4Na3 pH7.5, 20 mM NaCl) at 4°C. Cleavage of Trx-Lsd1 was carried out by incubating the entire preparation with 1.3 units of thrombin for 3.5 h at RT followed by dialysis against phosphate buffer using dialysis membrane with 12–14 kDa cutoff.

Circular Dichroism (CD)

CD spectroscopy was performed with a Jasco-715 (Jasco Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) spectropolarimeter using a 0.1 cm path length cell over the 195–260 nm range. The spectra were acquired every 1 nm with a 2 s averaging time per point and a 1 nm bandpass. Quadruplicates of the spectra were averaged, corrected for background, and smoothed. Protein concentrations were determined by UV at 280 nm using extinction coefficients of 52,955 M−1.cm−1 and 37,360 M−1.cm−1 for Trx-Lsd1 and Lsd1, respectively. The mean residue ellipticity (deg·cm2·dmol−1) was calculated from the corresponding number of residues of Trx-Lsd1 (588) and S-tagged-Lsd1 (458). The secondary structure of Lsd1 was estimated with the program Selcon3 using a 29-protein dataset of basic spectra [23].

Phosphorylation of Lsd1

Lsd1-DMPG-[3H]-triolein complexes (40 μg protein) in 50mM MOPS pH7, 5mM magnesium acetate, 1mM ATP, 5mM DTT were incubated in the presence and absence of 2 units of the catalytic subunit of PKA for 20 min at RT. The reaction was stopped by adding 10mM EDTA (final concentration). Lsd1-DMPG was phosphorylated under the same conditions in the presence of 50μCi of radiolabeled [γ-32P]-ATP. The reaction was stopped with Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Mass spectrometry

Phosphorylation reactions performed with Lsd1 complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE. Protein bands were excised, reduced and alkylated, and digested with trypsin (Promega V5111). Peptide extracts were analyzed by Maldi-tof. Linear mass spectra were also collected using alternative Maldi matrices 2,5-dihydroxy benzoic acid and sinapic acid. Peptide mass fingerprints were used for database searching with the Mascot® software (Matrix Science). For MS/MS analyses, samples were analyzed by reverse-phase micro-LC and online ESI-MS using an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer at the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory from the Univ. of Texas Health Science Center. Scaffold (version 010603) was used to search a database supplemented with the recombinant protein's sequence.

Lipase activity

Manduca sexta TGL was purified as previously described [24]. Substrate was prepared by incorporating triolein into Lsd1/DMPG complexes. For this purpose, triolein containing 2.1 mci/mmol of [9,10-3H] triolein was dried as a thin film in a glass vial. An aliquot of Lsd1/DMPG in phosphate buffer was added and vortexed for 30 sec. The preparation was incubated at RT for 30 min with interleaved vortexing every 10 min. Lipase activity was measured by incubating TGL (3μg) with 20 μl of substrate containing 2.5 nmol DMPG, 50 nmol TG and 0.05 nmol Lsd1 in 100 μl of buffer (100mM Tris pH 7.9, 0.5M NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 0.02% BSA, final concentrations) for 30 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped with 0.5 ml of chloroform-methanol-benzene 2:2.4:1 (v/v/v) and 8 μl of HCl 6N. Radiolabeled lipids from the organic phase were separated on TLC using hexanes:ethyl ether:formic acid (70:30:3 v/v/v) as developing solvent. Regions of the plate corresponding to TG, DG, MG and FFA were scrapped and quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Substrates containing control Lsd1 and PKA phosphorylated Lsd1 were assayed. Blank reactions did not contain enzyme. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated three times or more. TGL activity was expressed as nmol TG hydrolyzed/mg min.

Ultracentrifugation

Lsd1/DMPG complexes after thrombin cleavage were fractionated by ultracentrifugation in a KBr density gradient at 350,000g in a VTi 65.2 rotor as described before [25].

Other methods

SDS-PAGE was performed according to Laemmli and proteins were visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R staining. For Western Blotting, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Anti-S tag and anti-His tag monoclonal antibody was purchased from Novagen. Immunodetection was performed using the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and ECL chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Biosciences). The size of lipoprotein complex was determined by nondenaturing gradient PAGE in 4–20% gels for 12h at 120V.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overexpression and Purification of Trx-Lsd1 fusion protein

Lsd1 is tightly bound to the lipid droplets, but it can be partially dissociated with 8M urea and high concentration of detergents. However, purification of Lsd1 from LDs isolated from M. sexta adipocytes rendered insufficient amounts of protein to carry out biochemical studies. To circumvent this problem expression of recombinant Lsd1 (rLsd1) in E.coli was attempted. Lsd1 is a well conserved protein among insects. Multiple protein sequence alignment carried out with all Lsd1 sequences available from eight different insects produced a significant alignment. In particular, Lsd1 from Bombyx mori (lepidoptera) and Drosophila melanogaster (diptera) show high sequence identity (40.5%) in a 388 aminoacid overlap.

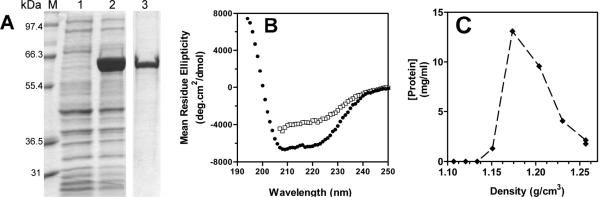

Drosophila rLsd1 was expressed as a fusion protein with thioredoxin (Trx-Lsd1) using the pET-32 Ek/LIC vector that also inserts a His-tag and an S-tag coding sequence between Trx and Lsd1. A thrombin cleavage site separates the Trx/His tag from S-tag/Lsd1. Expression of Trx-Lsd1 was attained in E.coli strain Rosetta 2. Maximal expression of rTrx-Lsd1 (65.7 kDa) occurred 2h after IPTG induction when Trx-Lsd1 was the major protein of the lysate (Fig 1A). Trx-Lsd1 was found in the insoluble fraction of the bacteria lysate. Solubilization was achieved by sonication in the presence of high concentrations of urea and detergents as described in Methods. Exploiting the insolubility of Trx-Lsd1 we removed contaminant proteins by washing the pellet several times with a buffer containing 6M urea, 0.3 % octylglucoside, 0.5M NaCl. Then Trx-Lsd1 was solubilized by sonication in 8M urea and 1% cholate. Once the protein was in solution it was possible to decrease the concentration of urea and cholate by dialysis to 2M and 0.01%, respectively. Significant aggregation of rLsd1 occurred at concentrations of urea below 2M. This procedure yielded a pure preparation of Trx-Lsd1 (Fig 1A). Given the insolubility of Trx-Lsd1 in the absence of denaturants, its cleavage with either thrombin or enterokinase was assayed in the presence of 2M urea. Although both proteases are active in 2M urea, and several experimental conditions were tested, an optimal condition for cleavage was not found. It was concluded that the cleavage sites of Trx-Lsd1 were not accessible to proteases.

Figure 1. Characterization of Trx-Lsd1.

A) SDS-PAGE: lane 1, bacterial lysate; lane2, bacteria lysate after IPTG; lane 3, purified Trx-Lsd1. B) Far-UV CD spectrum of Trx-Lsd1 in 2M urea buffer (□), and Trx-Lsd1/DMPG in phosphate buffer (●). C) Flotation density of Trx-Lsd1/DMPG in a KBr density gradient.

Only two PAT proteins, murine ADRP [26] and TIP47 [27], have been over-expressed so far as recombinant proteins. TIP47 was purified from the soluble fraction of cell lysate whereas recombinant ADRP localized in the insoluble fraction. Unlike Lsd1, these two proteins were soluble in Tris buffer after its purification. Although ADRP, TI47, and Lsd1 share similarities in the PAT region, Lsd1 shows a low overall identity - 17.5% - with the vertebrate proteins ADRP and TIP47.

Reconstitution of Trx-Lsd1 with lipids

To stabilize rLsd1 in aqueous buffer and obtain lipoprotein particles of Trx-Lsd1 we used the cholate dialysis method, which is amply used to prepare discoidal lipoproteins with apolipoproteins [28, 29]. Trx-Lsd1 in buffer containing urea and cholate was incubated with DMPG and subjected to exhaustive dialysis in phosphate buffer. A clear solution of Lsd1 was obtained after dialysis. This result indicated binding of Lsd1 to lipids and the formation of small lipoprotein particles (Trx-Lsd1/DMPG). The CD spectra of Trx-Lsd1 before and after dialysis showed that the protein gained α-helical structure upon binding to lipids (Fig 1B). Confirming the association of Lsd1 with phospholipid, ultracentrifugation of the lipoprotein complexes in a KBr gradient indicated that the concentration of Lsd1 was maximum in the fraction with a mean density of 1.185 g/cm3 (Fig 1C).

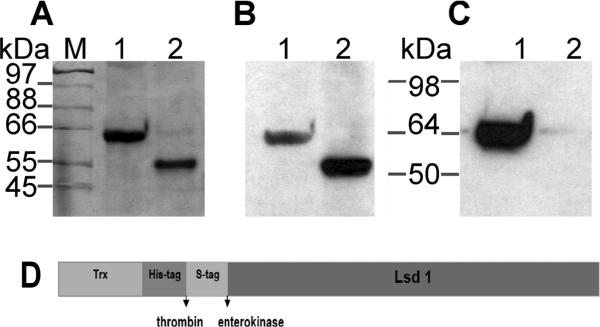

Thrombin cleavage of Trx-Lsd1 bound to lipids yielded a single product of 55kDa (Fig 2A). This apparent mass was slightly higher than the expected size (52kDa). The specificity of thrombin cleavage was verified by immunodetection with anti S-tag antibody that recognized both uncut Trx-Lsd1 and cleaved Lsd1 whereas anti His antibody only recognized uncut Trx-Lsd1 (Fig2 B-C). The removal of the 14kDa N-terminal domain (Trx-His) that was carried out during dialysis was confirmed by Western blot using the anti His antibody (data not shown). The identity of the 55kDa product was further confirmed by Maldi-tof, which unambiguously identified this protein band as Lsd1 from D. melanogaster, NP_732904.

Figure 2. Proteolytic Cleavage of Trx-Lsd1 in DMPG Complexes.

A) SDS-PAGE: Samples of Trx-Lsd1 uncut (lane 1), and after thrombin cleavage (lane 2) were separated by electrophoresis. B-C) Western blot analysis of the samples shown in panel A using anti S-tag (B) and anti His (C) antibodies.

Secondary structure of Lsd1

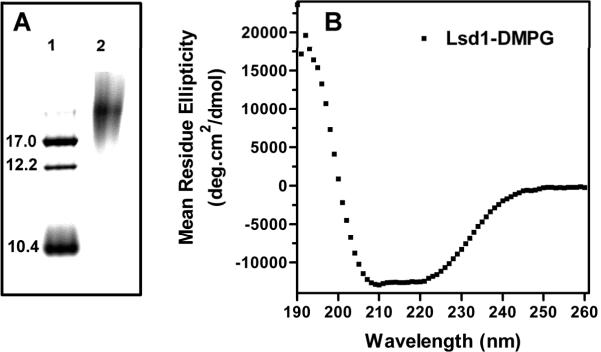

As expected, removal of the Trx-His N-terminal region from the fusion protein did not affect stability of the lipoprotein complexes. The lipoprotein particles of Lsd1 and DMPG formed a clear (low scattering) and stable solution in aqueous buffer. Analysis of the particle size by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis indicated that Lsd1/DMPG particles had an apparent diameter of 20 nm (Fig 3A).

Figure 3. Secondary structure of rLsd1.

A) Nondenaturing gel electrophoresis of rLsd1/DMPG complexes: Markers (Stoke diameters in nm) (lane 1); Lsd1/DMPG complexes (lane 2). B) CD spectrum of rLsd1 bound to DMPG.

The far-UV CD spectrum of Lsd1/DMPG showed the typical features of the spectra of α-helical proteins (Fig 3B). Estimation of the fractions of four structural components using the “Self-consistent” method (Selcon3) [23] indicated that the structure of Lsd1 bound to DMPG comprises 34% of α-helix, 16% β-pleated sheets, 21% turns and 29% random coil. A similar outcome was obtained using the programs nnPredict [30] (43% α-helical, 5% β and 52% random & turns), or GOR 4 [31] (51% α-helical, 8% β and 41% random & turns).

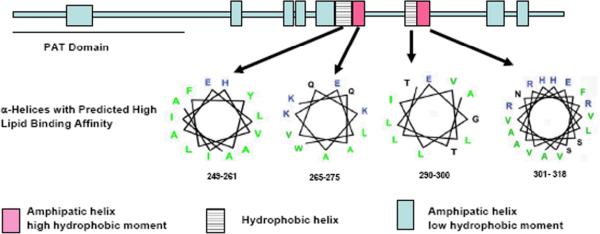

The predicted location of the α-helical regions of Lsd1 is shown in Fig 4. Analysis of the amphipathic character of the helices suggests that four of the helices, two highly amphipathic (265–275 and 301–318) and two hydrophobic helices (249–261 and 301–318), would be involved in binding to the lipid surface. The lipid binding regions of Drosophila Lsd1 are located at the central region of the molecule. The hydrophobic helices are likely to be buried in the lipid droplet, whereas the amphipathic helices would be anchored to the phospholipid surface through the nonpolar face of the helices and the stabilizing interactions of the positively charged residues with the phosphate groups of phospholipid. Other helices could be involved in lipid binding. However, they are characterized by smaller nonpolar faces or low hydrophobic moments.

Figure 4. Predicted α-helical regions of Lsd1.

Helical regions of Lsd1 (431aa) are indicated with rectangles. The PAT domain is located between residues 17–170. The locations of the 11 predicted helices are: 44–63, 170–178, 211–219, 221–228, 236–247, 249–261, 265–275, 290–300, 301–318, 357–371, and 380–389. Helical wheel diagrams of the four helices having a high lipid binding affinity are shown (charged residues are in blue, hydrophobic residues in green and uncharged polar residues in black).

Although Lsd1 contains a significant proportion of α-helical structure, a large extent of the polypeptide does not appear to fold and may not adopt a compact folded state suggesting that several regions of the protein may be available for interaction with other proteins, such as TGL. Noteworthy, the PAT domain is predicted to be a mostly unstructured region. It is also interesting to note that Lsd1 is a highly basic protein and does not have large stretches of highly hydrophobic regions. Analysis of the hydrophobicity and amphiphilicity of Lsd1 showed that only four helices clustered near the central region of the polypeptide, two largely hydrophobic and two highly amphipathic, would have a large tendency to bind to the lipid surface (Fig 4).

Effect of Lsd1 phosphorylation on TGL activity

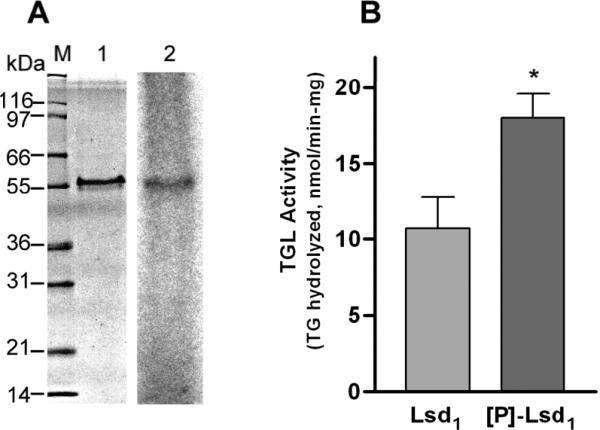

TGL is the major lipase found in the fat body of M. sexta and was identified as the homologous of CG 8552 from D. melanogaster [32]. A previous study showed that hormonal stimulation of lipolysis correlated with phosphorylation of Lsd1 in M.sexta [6]. Moreover, in vitro phosphorylation of isolated lipid droplets catalyzed by PKA enhanced both Lsd1 phosphorylation and the activity of TGL hydrolyzing TG contained in the lipid droplets [6]. These findings suggested a role of Lsd1 phosphorylation on TGL activation. The complexity of the lipid droplets did not allow determining whether Lsd1 phosphorylation activates lipolysis in a direct or in an indirect fashion, such as through the interaction with other proteins. To address this issue we investigated first whether Lsd1/DMPG was susceptible to PKA phosphorylation. Incubation of Lsd1/DMPG complexes with the catalytic subunit of PKA in the presence of [γ-32P]-ATP showed that Lsd1 reconstituted in DMPG complexes was phosphorylated (Fig 5A).

Figure 5. Effect of Lsd1 phosphorylation on TGL activity.

A) Lsd1 bound to DMPG was phosphorylated by PKA and [γ-32P]-ATP followed by SDS-PAGE (1) and autoradiography (2). B) TGL activity was assayed against rLsd1/DMPG/[3H]-triolein containing unphosphorylated (Lsd1) or phosphorylated ([P]-Lsd1) protein. Data represent the mean ± SEM (n=10). Statistical comparisons were made by Student's t test. Two tail P value was significant (*P=0.012).

Next we studied the effect of Lsd1 phosphorylation on TGL activity. For this purpose, Lsd1/DMPG particles were first loaded with radiolabeled triolein. Aliquots of Lsd1/DMPG/triolein complexes were then incubated with Mg-ATP in the presence or in the absence of PKA to obtain phosphorylated and control substrates, respectively. These substrates were subsequently incubated with TGL purified from the fat body of M. sexta. Additional blank reactions were carried out in parallel by incubating the substrate samples in the absence of lipase. This study showed that Lsd1 phosphorylation promotes a significant ~1.7-fold increase in TGL activity (Fig 5B). This finding supports a direct link between Lsd1 phosphorylation and TGL activation. The activation was slightly lower than the 2-fold activation that was observed when lipid droplets were phosphorylated in vitro with PKA [6]. The lower activation observed with lipoprotein complexes could be due to structural differences between the substrates and/or to the role of some other lipid droplet protein that is absent in this system.

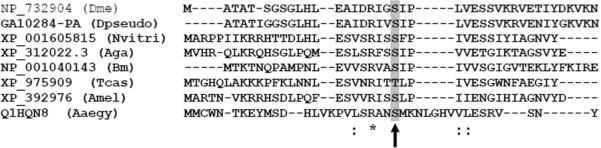

Lipoprotein complexes that were incubated with Mg-ATP in the presence or in the absence of PKA were subjected to mass spectrometry analysis to identify phosphorylation sites. Lsd1-derived peptides (23–24 unique peptides) were identified in 37–39 unique spectra. Ions (MH2+ 614.99) representing the peptide I(18)GSIPLVESSKR(29) were clearly detected in treated and untreated Lsd1 samples. Additionally, PKA-treated Lsd1 samples contained a strong peptide ion of m/z 654.93, which was absent from the control Lsd1 sample. MS/MS fragmentation identified this ion as representing the phosphorylated I(18)GpSIPLVESSK(29) peptide. The de-phosphorylated parent, a strong series of y ions (y3 to y11), and strong b4-98 ions were evident, unambiguously identifying the site of Lsd1 phosphorylation as Ser 20. This residue is located in the PAT domain of Lsd1 in a region that is predicted to be unfolded (Fig. 4). CD analysis carried out with both forms of the protein indicated that phosphorylation of Ser 20 did not modify the secondary structure of Lsd1 in the lipoprotein particles (data not shown). Six PKA consensus sites located at positions 20, 46, 84, 232, 291 and 373 are found in Dme Lsd1. Interestingly, among these putative phosphorylation sites, serine at position 20 is the only site that is absolutely conserved among all available Lsd1 sequences (Fig 6). Lsd1 from Tribolium castaneum Ser 20 is replaced by a threonine residue, which also belongs to a consensus PKA phosphorylation site. This conservation adds further support to the role of Ser 20 in the function of Lsd1.

Figure 6. Alignment of the N-terminal regions of Lsd1.

The alignment of the eight available Lsd1 sequences was performed using the T-Coffee program available at www.ebi.ac.uk/t-coffee. The accession numbers for the sequences are displayed in the figure. Dme, Drosophila melanogaster; Dpseudo, Drosophila pseudoobscura; Nvitri, Nasonia vitripennis; Aga, Anopheles gambiae; Bm, Bombyx mori; Tcas, Tribolium castaneum; Ame, Apis mellifera; Aaegy, Aedes aegypti. The arrow indicates Ser20. In Lsd1 from Tribolium castaneum Ser 20 is replaced by a threonine residue.

Altogether these findings demonstrate that the activity of TGL can be directly modulated by phosphorylation of Lsd1. Understanding the regulation of the lipolytic process is essential to the full understanding of the metabolism of triglycerides. The mechanism of basal lipolysis and the mechanism of activation of lipolysis are complex processes whose details are far from being fully understood in any system. The lipid droplet is recognized as an important organelle which accomplishes essential functions in adipocytes and therefore in the homeostasis of lipid metabolism of the organism [4]. The importance of studying these proteins is currently recognized. However, none of the potentially important proteins have been fully characterized from a functional or structural point of view, yet. Most of the knowledge of the lipolytic process has been achieved from studies carried out in 3T3 adipocytes [4]. In insects, the understanding of this process is in an early stage. Some aspects of the lipolytic process in these two systems are different. A clear difference with the mammalian system is that unlike HSL, insect TGL is constitutively phosphorylated and its level of phosphorylation is unaffected by hormonal stimulation [21]. Unlike HSL, which upon stimulation of the lipolysis is phosphorylated, activated and binds to the LD [33], stimulation of lipolysis in insects does not promote TGL translocation [6], and PKA catalyzed phosphorylation does not enhance TGL activity [6,34]. However, the fact that phosphorylation of Lsd1 directly modulates the activity of TGL resembles the mode of action of perilipin A. The mechanism by which phosphorylation of Lsd1 enhances the activity of TGL remains to be elucidated. Because activation of lipolysis does not involve a high affinity binding of cytosolic TGL to the lipid droplet we speculated that a change in the kinetic properties of the lipase could be responsible for the activation of TGL triggered by Lsd1 phosphorylation. This increase in the catalytic activity could be due to an increase in the accessibility of the lipase to the TG molecules. The possibility of reconstituting Lsd1 in lipoprotein particles will be useful to advance the understanding on the mechanism of activation of lipolysis in insects.

In conclusion, this study shows for the first time that association of Lsd1 with phospholipid, which to some extent resembles the arrangement of Lsd1 in the lipid droplet, provided an adequate environment that stabilized Lsd1 preventing protein aggregation and allowing folding. In this system Lsd1 adopted an α-helical conformation that is supported by the structure predictions from the amino acid sequence. Reconstitution of Lsd1 with lipids allowed to determine the effect of Lsd1 phosphorylation on the activation of the main lipase found in fat body adipocytes and, thus, in the control of the rate of lipolysis in insects. The possibility of reconstituting Lsd1 in lipoprotein particles makes possible to investigate the interaction of Lsd1 with other proteins. Likewise it could be beneficial for the studies on biochemical characterization of other lipid droplet-associated proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 64677 and Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- [1].Wolins NE, Brasaemle DL, Bickel PE. A proposed model of fat packaging by exchangeable lipid droplet proteins. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5484–5491. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ziegler R, Van Antwerpen R. Lipid uptake by insect oocytes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Beenakkers AM, Van der Horst DJ, Van Marrewijk WJ. Insect lipids and lipoproteins, and their role in physiological processes. Prog Lipid Res. 1985;24:19–67. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(85)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brasaemle DL. The perilipin family of structural lipid droplet proteins: Stabilization of lipid droplets and control of lipolysis. J Lipid Res. 2007 doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700014-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Murphy DJ. The biogenesis and functions of lipid bodies in animals, plants and microorganisms. Prog Lipid Res. 2001;40:325–438. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Patel RT, Soulages JL, Hariharasundaram B, Arrese EL. Activation of the lipid droplet controls the rate of lipolysis of triglycerides in the insect fat body. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22624–22631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Beller M, Riedel D, Jansch L, Dieterich G, Wehland J, Jackle H, Kuhnlein RP. Characterization of the Drosophila lipid droplet subproteome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1082–1094. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600011-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lu X, Gruia-Gray J, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Londos C, Kimmel AR. The murine perilipin gene: the lipid droplet-associated perilipins derive from tissue-specific, mRNA splice variants and define a gene family of ancient origin. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:741–749. doi: 10.1007/s00335-01-2055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Miura S, Gan JW, Brzostowski J, Parisi MJ, Schultz CJ, Londos C, Oliver B, Kimmel AR. Functional conservation for lipid storage droplet association among Perilipin, ADRP, and TIP47 (PAT)-related proteins in mammals, Drosophila, and Dictyostelium. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32253–32257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Londos C, Sztalryd C, Tansey JT, Kimmel AR. Role of PAT proteins in lipid metabolism. Biochimie. 2005;87:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Londos C, Brasaemle DL, Schultz CJ, Segrest JP, Kimmel AR. Perilipins, ADRP, and other proteins that associate with intracellular neutral lipid droplets in animal cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1999;10:51–58. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nakamura N, Fujimoto T. Adipose differentiation-related protein has two independent domains for targeting to lipid droplets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306:333–338. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00979-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Garcia A, Sekowski A, Subramanian V, Brasaemle DL. The central domain is required to target and anchor perilipin A to lipid droplets. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:625–635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Miyoshi H, Perfield JW, 2nd, Souza SC, Shen WJ, Zhang HH, Stancheva ZS, Kraemer FB, Obin MS, Greenberg AS. Control of adipose triglyceride lipase action by serine 517 of perilipin A globally regulates protein kinase A-stimulated lipolysis in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:996–1002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tansey JT, Huml AM, Vogt R, Davis KE, Jones JM, Fraser KA, Brasaemle DL, Kimmel AR, Londos C. Functional studies on native and mutated forms of perilipins. A role in protein kinase A-mediated lipolysis of triacylglycerols. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8401–8406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Teixeira L, Rabouille C, Rorth P, Ephrussi A, Vanzo NF. Drosophila Perilipin/ADRP homologue Lsd2 regulates lipid metabolism. Mech Dev. 2003;120:1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Welte MA, Gross SP, Postner M, Block SM, Wieschaus EF. Developmental regulation of vesicle transport in Drosophila embryos: forces and kinetics. Cell. 1998;92:547–557. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80947-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gronke S, Beller M, Fellert S, Ramakrishnan H, Jackle H, Kuhnlein RP. Control of fat storage by a Drosophila PAT domain protein. Curr Biol. 2003;13:603–606. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fauny JD, Silber J, Zider A. Drosophila Lipid Storage Droplet 2 gene (Lsd-2) is expressed and controls lipid storage in wing imaginal discs. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:725–732. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gade G, Auerswald L. Mode of action of neuropeptides from the adipokinetic hormone family. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2003;132:10–20. doi: 10.1016/s0016-6480(03)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Patel RT, Soulages JL, Arrese EL. Adipokinetic hormone-induced mobilization of fat body triglyceride stores in Manduca sexta: role of TG-lipase and lipid droplets. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2006;63:73–81. doi: 10.1002/arch.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Arrese EL, Flowers MT, Gazard JL, Wells MA. Calcium and cAMP are second messengers in the adipokinetic hormone-induced lipolysis of triacylglycerols in Manduca sexta fat body. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:556–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sreerama N, Venyaminov SY, Woody RW. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: inclusion of denatured proteins with native proteins in the analysis. Anal Biochem. 2000;287:243–251. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Arrese EL, Wells MA. Purification and properties of a phosphorylatable triacylglycerol lipase from the fat body of an insect, Manduca sexta. J Lipid Res. 1994;35:1652–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chetty PS, Arrese EL, Soulages JL. In Vivo Lipoprotein Binding Assay of the Insect Exchangeable Apolipoprotein, Apolipophorin-III. Protein Pept. Lett. 2003;10:469–473. doi: 10.2174/0929866033478681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Serrero G, Frolov A, Schroeder F, Tanaka K, Gelhaar L. Adipose differentiation related protein: expression, purification of recombinant protein in Escherichia coli and characterization of its fatty acid binding properties. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hickenbottom SJ, Kimmel AR, Londos C, Hurley JH. Structure of a lipid droplet protein; the PAT family member TIP47. Structure. 2004;12:1199–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jonas A, Kezdy KE, Wald JH. Defined apolipoprotein A-I conformations in reconstituted high density lipoprotein discs. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4818–4824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chetty PS, Arrese EL, Rodriguez V, Soulages JL. Role of Helices and Loops in the Ability of Apolipophorin-III To Interact with Native Lipoproteins and Form Discoidal Lipoprotein Complexes. Biochemistry. 2003;42:15061–15067. doi: 10.1021/bi035456i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kneller DG, Cohen FE, Langridge R. Improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by an enhanced neural network. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90154-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Garnier J, Gibrat JF, Robson B. GOR method for predicting protein secondary structure from amino acid sequence. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:540–553. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Arrese EL, Patel RT, Soulages JL. The main triglyceride-lipase from the insect fat body is an active phospholipase A(1): identification and characterization. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2656–2667. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600161-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Holm C. Molecular mechanisms regulating hormone-sensitive lipase and lipolysis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:1120–1124. doi: 10.1042/bst0311120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Patel RT, Soulages JL, Wells MA, Arrese EL. cAMP-dependent protein kinase of Manduca sexta phosphorylates but does not activate the fat body triglyceride lipase. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:1269–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]