Abstract

This study was designed to test the hypothesis that fetal adrenal nitric oxide synthase (NOS) is elevated in response to long term hypoxia (LTH). Pregnant ewes were maintained at high altitude (3,820 m) for approximately the last 100 days of gestation. Between days 138–141 of gestation, adrenal glands were collected from LTH fetuses and age-matched normoxic controls. qRT-PCR and Western analysis were used to quantify NOS expression and NOS distribution was examined by immunohistochemistry and double-staining immunofluorescence for eNOS and 17α hydroxylase (CYP17). nNOS was expressed at very low levels and with no differences between groups. Expression of eNOS was significantly greater in the LTH group compared with control. nNOS was distributed throughout the cortex while the greatest density of eNOS was observed in the zona fasciculata/reticularis area and eNOS co-localized with CYP17. We conclude that LTH enhances eNOS expression in the inner adrenal cortex which may play a role in regulation of cortisol biosynthesis in the LTH fetus.

Keywords: cortisol, steroidogenesis, immunohistochemistry

INTRODUCTION

Regulation of cortisol synthesis is essential for normal fetal growth and development. As in adults, the capacity to produce cortisol in response to stress is paramount in the ability of the late gestation fetus to survive physiological stressors. One such stressor is hypoxia, which represents a threat to fetal survival and well-being. It is evident that hypoxic stress increases plasma cortisol in the ovine fetus.1, 2 The acute phase of hypoxia has been studied extensively, but much less is known about the effects of long-term hypoxia (LTH).

Our laboratory has studied the effect of LTH on the sheep fetus. We maintain pregnant ewes at high altitude (3,820 m, Po2 ~ 60mmHg); from approximately day 40 of gestation to near term (term = 146 days. We have clearly shown that the sheep fetus adapts to LTH maintaining basal plasma cortisol at concentrations comparable to normoxic controls3, 4 despite exhibiting elevated basal plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels.5 The adaptive mechanisms involved in the preservation of normal basal cortisol levels in the face of this chronic stressor have not been fully elucidated. We have demonstrated that expression of the ACTH receptor, CYP11A (cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage) and CYP17 (17α-hydroxylase), key steroidogenic enzymes in cortisol synthetic pathway, were down-regulated in the fetal adrenal in response to LTH.6 Interestingly, although the normal ontogenic changes in basal plasma cortisol levels are maintained in the LTH fetus, in response to a secondary stressor, these fetuses exhibit enhanced cortisol production. Clearly, while the adaptive changes in expression of key steroidogenic genes provide a mechanism by which the fetus circumvents elevations in basal cortisol production in response to LTH, other factors likely play a role in governing cortisol production in these fetuses.

One potential mechanism may be through regulation of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and subsequent production of nitric oxide (NO). Although the most studied function of NO is its effect on vascular smooth muscle, increasing evidence suggests that NO plays a role in the regulation of steroidogenesis. NO has been shown to inhibit steroidogenesis in ovarian tissue of women,7 pigs,8, 9 rabbits10, 11, rats12 and NOS inhibitors increase testosterone secretion in Leydig cells.13 Immobilization stress also increased NO in adult rat testis and reduced production of testosterone.14 All three NOS isoforms, endothelial NOS (eNOS), neuronal NOS (nNOS) and inducible NOS (iNOS), have been demonstrated in the pig testes.15

Although less is known about the effects of NO on adrenal steroidogenesis, NO inhibits basal, ACTH-, and angiotensin II-induced aldosterone production in adult bovine zona glomerulosa cells.16 NO inhibition of aldosterone was also shown to be cGMP-independent 17 and reversed by NOS inhibitor thiocitrulline.18 NOS inhibition also increased aldosterone production in humans in vivo.19 In vitro, rat zona fasciculata cells exposed to different NO donors, and the NOS substrate L-arginine produced less significantly less glucocorticoid,20, 21 a likely consequence of NO-mediated inhibition of key rate-limiting steps in the steroidogenic pathway.22

These data together with evidence that NOS may be regulated by hypoxia23–25 suggest that NO inhibition of cortisol synthesis might be one of the possible mechanisms involved in our previously reported endocrine adaptations of ovine fetuses to LTH.3–5 However, to date, there are no data regarding the presence and distribution of the various NOS isoforms in the fetal adrenal. The present study was designed to determine the expression and distribution of NOS in sheep fetal adrenal cortex and to test the hypothesis that LTH enhances adrenal NOS expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Pregnant ewes were maintained at high altitude (3,820 m, maternal Po2 ~ 60 mmHg) from approximately day 40 of gestation to near term (term = 146 days) in our well-established model for LTH5, 6, 26 using procedures approved by the Loma Linda University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and guidelines in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Following transportation to the vivarium, maternal hypoxia was maintained by nitrogen infusion through a maternal tracheal catheter. Fetal adrenal glands were obtained between days 138–141 of gestation from LTH and age-matched normoxic controls. The methodology was performed as we have previously described in detail.5, 6 The adrenal glands were either snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for immunohistochemistry.

Western Analysis

Fetal adrenal glands were cut in half along the longitudinal axis, placed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS 1X; GIBCO, #70011-044, Carlsbad, CA), and the cortex was micro-dissected from the capsule and medulla. The cortical tissue was homogenized in 200µl lysis buffer (20mM HEPES-KOH, 10mM KCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 1mM EDTA, 167mM dithiothreitol, 100mM PMSF, 5µg/ml Leupeptin, 0.8µg/ml aprotinin). The mixture was centrifuged at 14000 × g for 15 minutes and the supernatant collected. Total protein was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Total protein (20 µg for eNOS (n = 7 normoxic controls; n = 8 LTH), 60 µg for nNOS and iNOS (n = 8 normoxic controls; n = 8 LTH) was loaded into freshly prepared SDS-PAGE gels (7.5% polyacrylamide). Molecular weights for nNOS, eNOS, and iNOS are reported as approximately 155, 140, and 130 kDa respectively. Electrophoresis was performed at 100 V for 100 minutes in Tris/Glycine/SDS (Bio-Rad). Protein was transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) at 0.36A for 90 minutes in Tris/Glycine buffer (Bio-Rad) on ice. The membranes were then blocked overnight at 4C in Tris buffered saline (Bio-Rad) containing 5% non-fat dry milk (Bio-Rad), 0.01% Tween 20. Primary antibodies were mouse anti-eNOS (1:250), mouse anti-nNOS (1:500) or mouse anti-iNOS (1:100) (all from BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA #610296, #610308, and #610599, mouse anti- eNOS, -nNOS, -iNOS respectively) diluted in blocking solution. Secondary antibody was horse-radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA #SC-2005) 1:1000 for all NOS isoforms. The membranes were subjected to enhanced chemiluminescence using Chemiglow Reagent (Alpha Innotech) and visualized by using the ChemiImager (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA) digital imaging system. Band intensities were measured and analyzed using AlphaEase software (Alpha Innotech). Relative density was normalized by loading equal protein amounts. In addition, a standard was run in every gel and sample values were expressed as densitometric units relative to the standard (relative optical density) as previously described for use in our laboratory27, 28. Samples from each animal were run in duplicate, and mean of these duplicates represented the density of NOS protein for each animal. The values from each animal were then used to calculate the mean±S.E.M. for each treatment group. The data were analyzed by Student’s t-test and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Quantitative Real time (RT) PCR quantification of mRNA

As we have previously described6, 29, total RNA was prepared from adrenal cortex (n=6 for each group) using a total RNA extraction kit (RNAqueous-4PCR, Ambion, Inc., Foster City, CA) Purity of RNA was assessed at A260 and A280 and only RNA with 260/280 ratios of 1.8–2.0 were used. This procedure includes a DNase I treatment step during extraction. Reverse transcription was performed using 1 µg total RNA using oligo dT as the primer and Superscript II (Invitrogen, Inc, Carlsbad, CA) as reverse transcriptase in a reaction volume of 20 µl. RNA is initially denatured for 5 minutes at 95°C prior to first strand synthesis at 42°C for 50 minutes and 15 minutes at 70°C. For all genes of interest, even though we DNase treat the RNA samples, we performed control reactions in which the reverse transcriptase was purposely omitted. Primer sequences used for quantitative real-time (qRT) PCR are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| Gene | Species | Accession Number | Primer | Sequence (5‘-3’) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nNOS (NOS1) |

Bos taurus |

XM_867630 | Forward Reverse |

AAA CCA CCA GCA CCT ACC AG TCT GAG GTT CCC TTT GTT GG |

| iNOS (NOS2) |

Bos taurus |

NM_001076799 | Forward Reverse |

AAG GCA GCC TGT GAG ACA TT CAG ATT CTG CTG CGA TTT GA |

| eNOS (NOS3) |

Bos taurus |

NM_181037 | Forward Reverse |

TCT TCC ACC AGG AGA TGG TC AGA GGC GTA CAG GAT GGT TG |

Real time PCR was performed using 1 to 5 µl (50 to 250 ng RNA equivalents) of first strand reaction per PCR reaction. All PCR reactions were performed in triplicate. The amount of cDNA needed per reaction is gene dependent and was determined by an initial PCR to ascertain that the amount of cDNA is within the linear amplification range for RT-PCR. Sybr Green was utilized as the fluorophore and a PCR mastermix using hot-start Taq polymerase supplied (Biorad, Inc.) using a volume of 20 µl per reaction. We utilized a Biorad iCycler equipped with the real-time optical fluorescent detection system and four filters including Sybr Green. A general three step PCR was used with a denaturation at 95°C for 45 sec, annealing (oligo specific but typically 55–60°C) for 30 sec and 72°C extension for 45 sec. For each RT reaction, we used cyclophillin as a ‘house keeping’ mRNA. An artificial 100 base single stranded DNA standard was used to generate a standard curve for quantification of starting cDNA concentrations.

Criteria for RT-PCR primers include: PCR amplicon must yield a single product (For all genes of interest, the amplicons were verified positive by Sanger dideoxy sequencing); a dilution curve of cDNA must yield a slope that is the same as generated by the standard DNA(100% + 10% ‘efficiency’ where 100% = Δ3 Ct/log cDNA input), and a post-amplification melt curve analysis of product must repeatedly demonstrate one product.

Immunohistochemistry

Fetal adrenals were fixed whole in 4% paraformaldehyde for ~24 hrs then placed in 70% EtOH until paraffin-embedding. 10µm longitudinal sections of paraffin-embedded tissue were cut, mounted on microscope slides. The slides were deparaffinized then immersed in fresh xylene. Sections were rehydrated by immersion in a graded series of alcohols and deionized water. Antigen retrieval was performed for 5 min using proteinase K solution (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA #S302030) for 5 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by with 3% H2O2 and nonspecific binding blocked with 10% normal goat serum, with 0.3% triton X in ChemMate antibody dilution buffer (Ventana, Tucson, CA #ADB250) before incubation with primary antibody (1:100 for eNOS; and 1:1000 for nNOS) followed by incubation with secondary antibody. Primary and secondary antibodies were the same as for Western analysis, and were diluted in 2% normal goat serum and 0.1% triton X, in ChemMate antibody dilution buffer. Sections in which the antibody dilution mixture was used instead of the primary antibody served as negative controls. Sections were incubated with avidin-biotin complex (ABC; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA PK-6100 or PK-6101) and colored with the chromagen diaminobenzidine (DAB; DAKO #K3466 counterstaining with hematoxylin. After sections were dehydrated in a graded series of alcohols and xylene, slides were coverslipped with Permount mounting medium (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA #SP15–100). Sections were viewed under brightfield microscopy and photomicrographs taken using a Spot camera with Capture software (Diagnostic Instruments Inc. Sterling Heights, MI).

Immunofluorescence double staining

Adrenal glands were cryosectioned (8 µm transverse sections), mounted onto slides and stored at −80C. For analysis, the slides were brought to room temperature then air dried and fixed in ice-cold acetone. The sections were washed twice in 0.1M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently enclosed with Super Pap Pen (Invitrogen). The sections were then incubated with 10% normal goat serum, 0.3% triton X 100 in ChemMate antibody dilution buffer (Ventana, #ADB250) at room temperature for 30 minutes to block nonspecific binding of primary antibody. The sections were incubated with 1:20 mouse anti-eNOS (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA #610296) then washed with 0.1M PBS and incubated with Alexa fluor 594 (red) labeled donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:100; Invitrogen #A21203). The sections were then washed in 0.1 M PBS. For CYP17 detection, the sections were treated identically through the primary antibody step where they were incubated with both primary (1:1000 rabbit anti-CYP17, kindly provided by Dr. Allen Conley, UC Davis); and secondary (1:500 of secondary antibody; Alexa fluor 488 (green) labeled goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen #A11078)) antibodies . The sections were then washed, covered with Vectashield™ hard-set mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Labs #H-1500). The sections were viewed under fluorescence microscopy, photomicrographs taken and overlaid using SPOT Advanced (version 4.6) software (Diagnostic Instruments Inc.).

RESULTS

Western Analysis

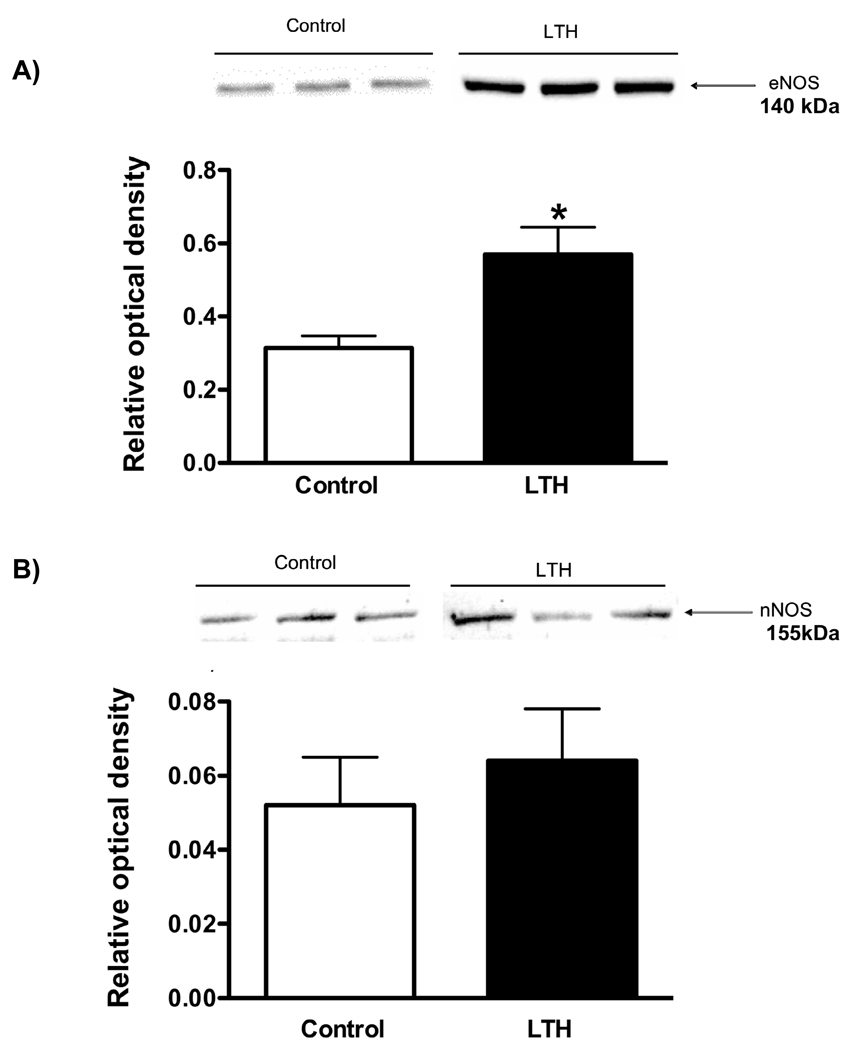

eNOS was abundantly expressed in both control and LTH fetal adrenal cortical tissue (Figure 1A) however expression for the LTH group were significantly higher (p<0.05) than control (0.55 +/− 0.08 LTH vs. 0.28 +/− 0.05 control, relative optical density units). nNOS protein was expressed in both groups with no difference between control and LTH adrenals (Figure 1B). However, the difference in relative protein abundance between eNOS and nNOS is highlighted by the scale difference between Figure 1A and 1B. It is also important to note that the amount of total protein loaded for nNOS was three times greater than that loaded for eNOS. Overall, eNOS was the dominant NOS isoform expressed about thirty fold more than nNOS. iNOS was not detected by Western analysis in adrenal cortical tissue from either normoxic or LTH fetal sheep.

Figure 1.

Protein expression for eNOS (A) and nNOS (B) as determined by Western analysis. All values represent mean+/-SEM relative optical density units. Representative immunoblots are illustrated above the corresponding histogram. (*p<0.05 LTH vs. control) n=8 for each group

qRT-PCR

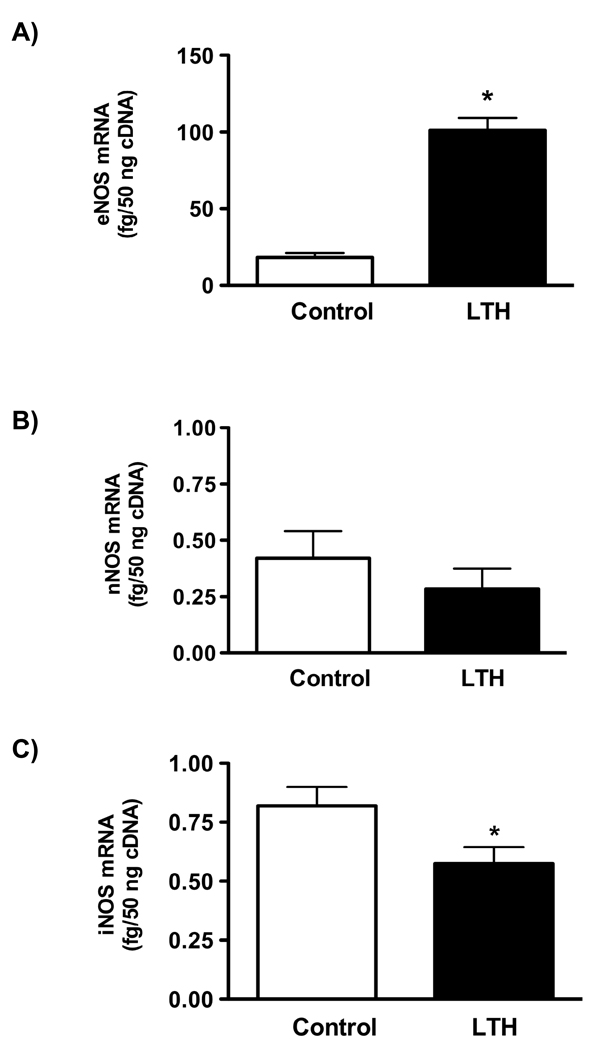

As determined by qRT-PCR, the concentration of mRNA for eNOS was significantly higher (p<0.001) in LTH fetal adrenal glands compared to normoxic controls (Figure 2A ). Message levels for nNOS did not differ between groups and were dramatically lower than those observed for eNOS (Figure 2B) confirming the results obtained from Western analysis. In contrast to the lack of protein expression, iNOS mRNA was measurable, albeit in low amounts, in both control and LTH adrenal cortical tissue (Figure 2C). Values for iNOS were significantly lower in the LTH group compared to control (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Concentrations of (A) eNOS (B) nNOS and , (C) iNOS mRNA from the first strand synthesis reaction. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the amount of mRNA for each gene of interest as described in METHODS. All values represent mean ± SEM, n=8 for each group. (*p<0.01 for LTH vs. control)

Immunohistochemistry

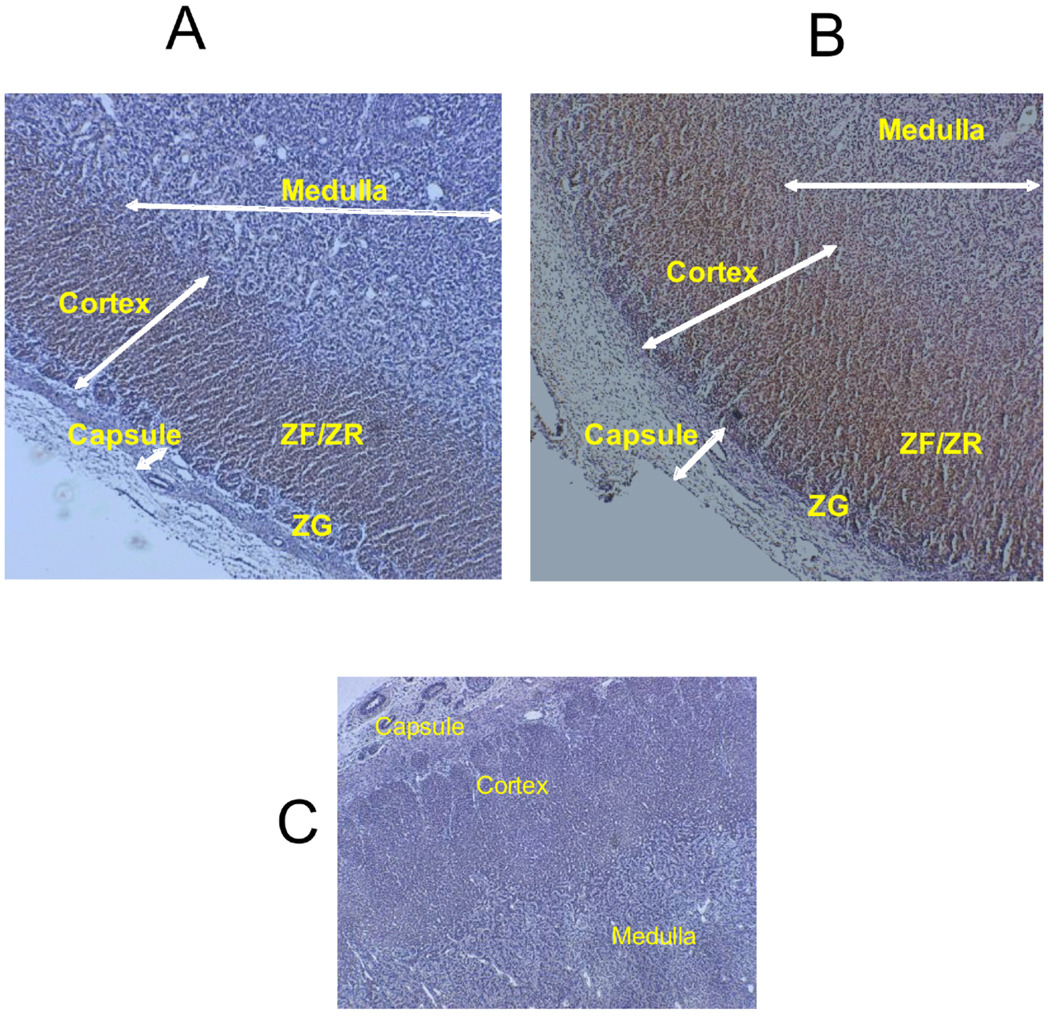

In the normoxic adrenals, eNOS was primarily localized in the inner cortex (ZF/ZR) almost entirely sparing the outer cortex with minimal staining in the medulla (Fig. 3A). In the LTH adrenals eNOS was distributed throughout the cortex and medulla, with the most intense staining in the ZF/ZR (Figure 3B). For nNOS, staining was similar for both control and LTH adrenals with primary distribution of stain in the cortex (Figure 4, A and B). Staining for iNOS was undetectable in either group (Data not shown).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical localization of adrenal eNOS from (A) normoxic control and (B) LTH fetuses. C illustrates the negative control (lack of primary antibody). The presence of eNOS is illustrated by the brown staining. The magnification is 40x. ZG= zona glomerulosa, FF/ZR= zona fasiculata/zona reticularis

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical localization of adrenal nNOS from (A) control and (B) LTH fetuses. The presence of eNOS is illustrated by the brown staining. The magnification is 40x.

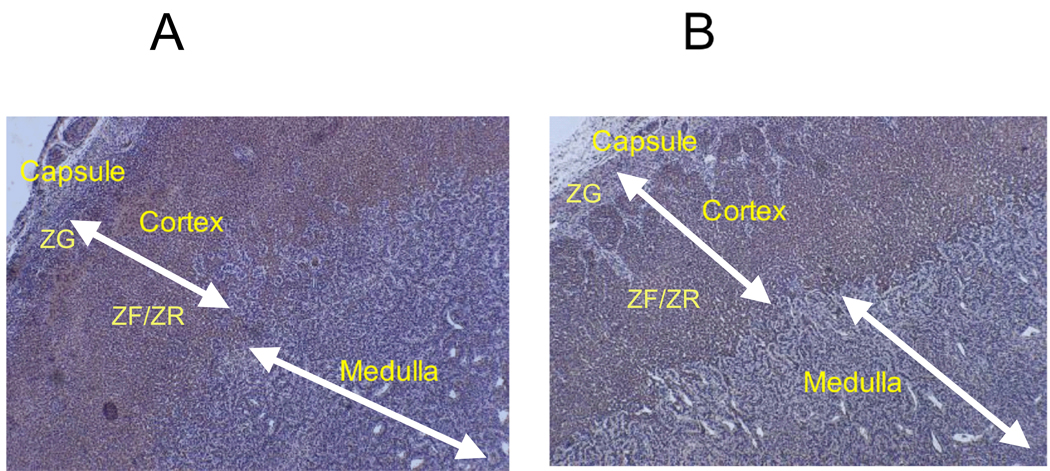

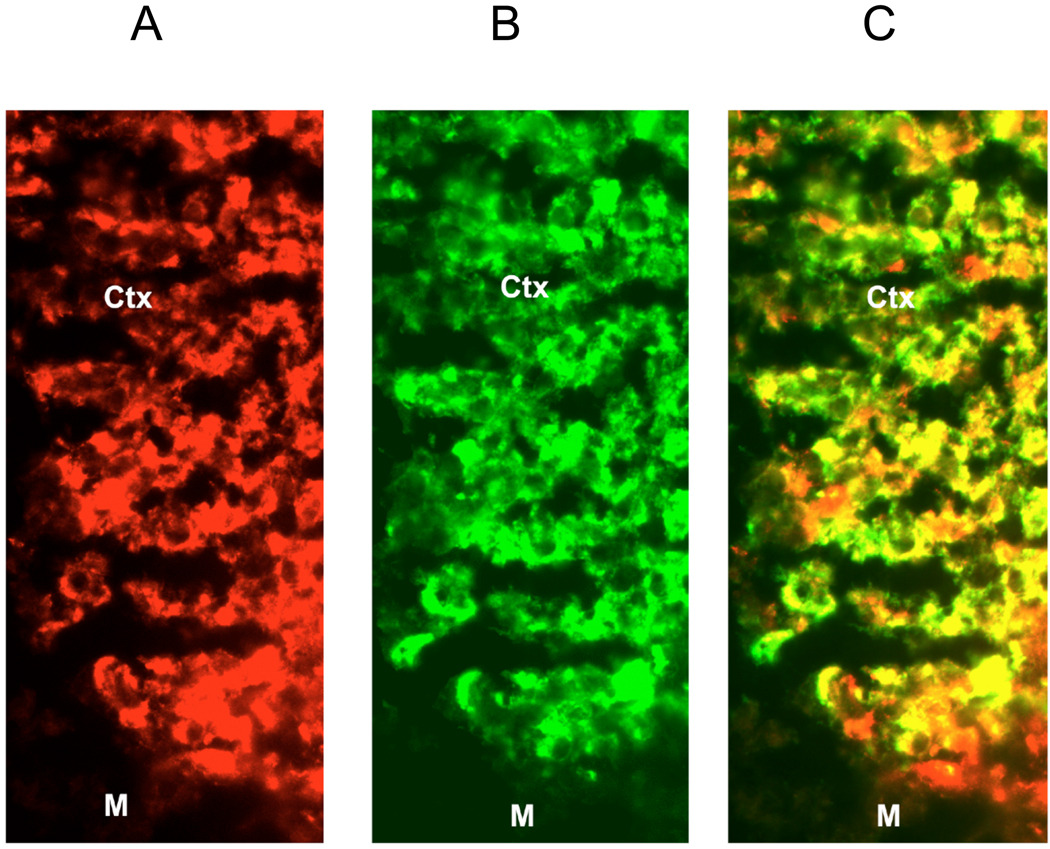

Immunofluorescence

A representative section of adrenal cortex illustrates localization of eNOS and CYP17 proteins in the inner cortex (ZF/ZG) toward the medulla (Figure 5). eNOS, represented by red fluorescence, was detected throughout the cortex with slightly lower intensity of the red fluorescence in the ZG (area not shown). CYP17, represented by green fluorescence, localized to the inner cortex of ZF/ZR, and was not detected in the ZG as expected (area not shown). Large areas of yellow fluorescence reflect the co-localization of eNOS and CYP17, indicating the presence of eNOS in adrenocortical cells.

Figure 5.

Representative fluorescent immunohistochemical localization of (A) eNOS and (B) CYP17 in the inner region of the adrenal cortex. C represents the merged images illustrating co-localization of eNOS and CYP-17 (areas of yellow) M- medulla, Ctx - inner region of the adrenal cortex. Magnification is 40x.

DISCUSSION

We previously demonstrated that under conditions of LTH, the ovine fetus undergoes significant adaptive changes at the level of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Despite elevations in basal ACTH secretion5, basal plasma cortisol concentrations are maintained within the range observed for normoxic control fetuses3, 4. The mechanism(s) involved in this critical adaptive response remains undefined. One potential mechanism is nitric oxide generation through regulation of NOS. In the present study, we found that eNOS is significantly up regulated in the adrenal cortex of the LTH fetus. To our knowledge, these are the first studies to not only describe the expression and distribution of NOS in the fetal adrenal, but more importantly, to demonstrate the effect of LTH on up regulation of eNOS.

Nitric oxide, a gas synthesized by a family of nitric oxide synthases, exerts a wide range of physiologic functions. The most studied function of NO is its effect on vascular smooth muscle. A major mechanism by which NO mediates cellular signaling in vascular smooth muscle is via activation of soluble guanylate cyclase. NO binds the heme group of soluble guanylate cyclase altering enzyme conformation and increasing its activity leading to elevation of intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) with subsequent activation of protein kinase G (PKG) resulting in vascular relaxation 30. NO has also been shown to have a profound effect on steroidogenesis in endocrine tissues. Unlike in vascular tissue however, the effects of NO on steroidogenesis seems to be cGMP-independent.17 Nitric oxide appears to competitively interact with the oxygen binding site of key steroidogenic enzymes like P450scc (CYP11A1) and P450c17 (CYP17).31 Since these enzymes use several rounds of attack of the heme-oxygen complex on the steroid substrate Peterson et al.,32 suggested that such multi-step targets would be more sensitive to NO inhibition than other enzymes such as, P450c21 (CYP21) or P450c11 (CYP11B).

The competitive interaction of NO with the oxygen-binding site of steroidogenic enzymes makes this compound an effective inhibitor of steroidogenesis. Indeed, NO has been clearly shown to inhibit steroidogenesis in a wide range of endocrine tissues including ovary11, 33, testes15 and adrenal cells.18, 21 At the level of the adrenal, the most widely studied effects of NO on steroid production have been on aldosterone synthesis where NO has been clearly shown to be a negative regulator. Although there is less information regarding the role of NO in glucocorticoid production, NO donors decreased both un-stimulated and ACTH-stimulated corticosterone production in rat zona fasciculata cells 20, 21. In contrast, NOS inhibition resulted in enhanced glucocorticoid output.20 Adams et al.,34 also found NO to act as a negative inhibitor of corticosterone synthesis.

Although the inhibitory effects of NO on steroidogenesis are clear, there is some controversy on the source of NO in endocrine tissue. The expression and distribution of NOS in the adrenal has been studied in a wide range of species with varying results. nNOS has been shown to increase in the adrenal cortex of rats following immobilization stress35, 36 while eNOS expression has been demonstrated in rat zona glomerulosa36, 37 and fasciculata 37. In contrast, Hanke and Campbell18 found that cultured bovine adrenal zona glomerulosa cells do not have detectable NOS. However, adrenal endothelial cells showed both enzymatic and immunoreactive eNOS. The authors suggested that these differences might be the result of either species specificity or as a result of cell culture conditions on adrenal NOS expression.

Data from the present study clearly demonstrate the presence of both eNOS and nNOS in adrenal cortical tissue of near term fetal sheep. For eNOS, immunohistochemical staining was most intense in the ZF/ZR region of the cortex in both control and LTH adrenals. This is similar to the distribution of eNOS staining reported in the adult ovine adrenal.32 However in the same study, the authors were unable to demonstrate the presence of nNOS. In contrast, we observed clear immunohistochemical staining for nNOS in the adrenal cortex of both control and LTH fetuses. The similar presence of nNOS was further confirmed by Western analysis as well as qRT-PCR albeit in relatively low abundance compared to that for eNOS. The reason for differences in adrenal cortical nNOS expression between adult and fetus may be due to developmental changes. Although we demonstrated iNOS mRNA at very low expression levels, it was undetectable with Western analysis or immunohistochemistry. This is consistent with earlier studies in adult ovine32, rat and human adrenal cortex 36 as well as in bovine zona glomerulosa cells18 demonstrating the absence of adrenal iNOS. Unlike the other NOS isoforms, iNOS activation is calcium independent and is only regulated at the level of expression, which would be ineffective as a method of controlling steroidogenesis.

In the present study, immunofluorescent dual labeling of the ZF/ZR demonstrated co-localization of eNOS with CYP-17, a key enzyme involved in cortisol synthesis. This information further strengthens the concept that adrenal cortical cells express eNOS and that NO produced locally may play a role in local regulation of cortisol synthesis. Endogenous generation of NO from ZF/ZR cells has also been suggested to occur through constitutively expressed eNOS in the rat.37 Irrespective of differences in species, developmental or the specific cellular localization of eNOS, the adrenal cortex is exposed to NO.

The concept that hypoxia can regulate NOS expression has precedence in a range of studies and tissues. Mitochondrial NOS (mtNOS) in cardiac tissue of male rats exposed to high altitude (4,340m) for 21 days increased 58% over sea level values.38 Exposure for longer periods of time (months) also resulted in up regulation of mtNOS.39 The authors concluded that high altitude hypoxia triggers a key physiological adaptation that upregulates NOS activity. These changes were correlated with an increase in hematocrit that further suggests a common mediator for erythropoietin and mtNOS, HIF-1α.

Hypoxia has also been shown to increase eNOS expression and NO production in microvessels in the heart of pigs.40 Another study showed that hypoxia stimulates the binding of eNOS with Hsp90 and activates the PI3-Akt pathway leading to eNOS phosphorylation and increased NO production.24 Our group has previously shown that LTH enhances eNOS mRNA and protein in ovine uterine arteries.23 In the present study we clearly demonstrated that LTH also induces expression of eNOS in the fetal adrenal cortex. In contrast, Murata et al.,41 observed a reduction in eNOS expression and function in organ cultured pulmonary arteries following hypoxia (5% O2 for 7 days). The same researchers also observed that hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension reduced NO production by impairing the interaction of eNOS with its regulatory proteins.42 Other workers have observed that hypoxia decreases eNOS expression in fetal while increasing the same in adult guinea pig heart43 and lung.44 Taken together, data from these studies clearly demonstrate that hypoxic exposure can regulate eNOS expression. It also becomes apparent that there is tissue and species specificity to the effects of hypoxia on eNOS expression. Under normoxic conditions, upregulation of eNOS could also occur as a result of reduced de novo NO production.45 However, under hypoxic conditions, it appears that eNOS is upregulated by mechanisms described above.

In conclusion, we have shown for the first time that the ovine fetal adrenal cortex expresses constitutive NOS (nNOS and eNOS). Further, LTH enhances expression of adrenal cortical eNOS. These data strengthen the hypothesis that enhanced LTH induced changes in NO production may be a mechanism by which the LTH fetus prevents elevations in basal cortisol secretion. We suggest that the enhanced eNOS expression represents elevated capacity for NO production and increased potential for regulation of cortisol synthesis under conditions of LTH.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD33147 (DAM) and HD31226 (CAD)

REFERENCES

- 1.Challis JR, Sloboda D, Matthews SG, et al. The fetal placental hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, parturition and post natal health. MolCell Endocrinol. 2001;20(185):135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner DS, Fletcher AJ, Fowden AL, Giussani DA. Plasma adrenocorticotropin and cortisol concentrations during acute hypoxemia after a reversible period of adverse intrauterine conditions in the ovine fetus during late gestation. Endocrinology. 2001;142:589–598. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.2.7980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imamura T, Umezaki H, Kaushal KM, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia alters endocrine and physiologic responses to umbilical cord occlusion in the ovine fetus. JSocGynecolInvestig. 2004;11:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi K, Umezaki H, Kaushal KM, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia alters ovine fetal endocrine and physiological responses to hypotension. AmJPhysiol RegulIntegrComp Physiol. 2004;287:R209–R217. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00701.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers DA, Bell PA, Hyatt K, Mlynarczyk M, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia enhances proopiomelanocortin processing in the near-term ovine fetus. AmJPhysiol RegulIntegrComp Physiol. 2005;288:R1178–R1184. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00697.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers DA, Hyatt K, Mlynarczyk M, Bird IM, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia represses the expression of key genes regulating cortisol biosynthesis in the near-term ovine fetus. AmJPhysiol RegulIntegrComp Physiol. 2005;289:R1707–R1714. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00343.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Voorhis BJ, Dunn MS, Snyder GD, Weiner CP. Nitric oxide: an autocrine regulator of human granulosa-luteal cell steroidogenesis. Endocrinology. 1994;135:1799–1806. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.5.7525252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masuda M, Kubota T, Aso T. Effects of nitric oxide on steroidogenesis in porcine granulosa cells during different stages of follicular development. EurJEndocrinol. 2001;144:303–308. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1440303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masuda M, Kubota T, Karnada S, Aso T. Nitric oxide inhibits steroidogenesis in cultured porcine granulosa cells. MolHumReprod. 1997;3:285–292. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.4.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gobbetti A, Boiti C, Canali C, Zerani M. Nitric oxide synthase acutely regulates progesterone production by in vitro cultured rabbit corpora lutea. JEndocrinol. 1999;160:275–283. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1600275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamauchi J, Miyazaki T, Iwasaki S, et al. Effects of nitric oxide on ovulation and ovarian steroidogenesis and prostaglandin production in the rabbit. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3630–3637. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsube K, Mikuni M, Matousek M, Brannstrom M. Effects of a nitric oxide donor and nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on luteinizing hormone-induced ovulation in the ex-vivo perfused rat ovary. HumReprod. 1999;14:2537–2543. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.10.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobashi M, Fujisawa M, Yamazaki T, et al. Inhibition of steroidogenesis in Leydig cells by exogenous nitric oxide occurs independently of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (star) mRNA. ArchAndrol. 2001;47:203–209. doi: 10.1080/014850101753145915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostic T, Andric S, Kovacevic R, Maric D. The involvement of nitric oxide in stress-impaired testicular steroidogenesis. EurJPharmacol. 1998;346:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HC, Byun JS, Lee TK, Jeong CW, Ahn M, Shin T. Expression of nitric oxide synthase isoforms in the testes of pigs. AnatHistolEmbryol. 2007;36:135–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.2006.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanke CJ, O’Brien T, Pritchard KA, Jr, Campbell WB. Inhibition of adrenal cell aldosterone synthesis by endogenous nitric oxide release. Hypertension. 2000;35:324–328. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanke CJ, Drewett JG, Myers CR, Campbell WB. Nitric oxide inhibits aldosterone synthesis by a guanylyl cyclase-independent effect. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4053–4060. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanke CJ, Campbell WB. Endothelial cell nitric oxide inhibits aldosterone synthesis in zona glomerulosa cells: modulation by oxygen. AmJPhysiol EndocrinolMetab. 2000;279:E846–E854. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.4.E846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muldowney JA, III, Davis SN, Vaughan DE, Brown NJ. NO synthase inhibition increases aldosterone in humans. Hypertension. 2004;44:739–745. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000143852.48258.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cymeryng CB, Dada LA, Podesta EJ. Effect of nitric oxide on rat adrenal zona fasciculata steroidogenesis. JEndocrinol. 1998;158:197–203. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1580197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cymeryng CB, Dada LA, Colonna C, Mendez CF, Podesta EJ. Effects of L-arginine in rat adrenal cells: involvement of nitric oxide synthase. Endocrinology. 1999;140:2962–2967. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.7.6848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drewett JG, ms-Hays RL, Ho BY, Hegge DJ. Nitric oxide potently inhibits the rate-limiting enzymatic step in steroidogenesis. MolCell Endocrinol. 2002;194:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao D, Bird IM, Magness RR, Longo LD, Zhang L. Upregulation of eNOS in pregnant ovine uterine arteries by chronic hypoxia. AmJPhysiol Heart CircPhysiol. 2001;280:H812–H820. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen JX, Meyrick B. Hypoxia increases Hsp90 binding to eNOS via PI3K–Akt in porcine coronary artery endothelium. Lab Invest. 2004;84:182–190. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi Y, Baker JE, Zhang C, Tweddell JS, Su J, Pritchard KA., Jr Chronic hypoxia increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase generation of nitric oxide by increasing heat shock protein 90 association and serine phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2002;91:300–306. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000031799.12850.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ducsay CA. Fetal and maternal adaptations to chronic hypoxia: prevention of premature labor in response to chronic stress. Comp BiochemPhysiol A MolIntegrPhysiol. 1998;119:675–681. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(98)01004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mlynarczyk M, Imamura T, Umezaki H, Kaushal KM, Zhang L, Ducsay CA. Long-term hypoxia changes myometrial responsiveness and oxytocin receptors in the pregnant ewe: differential effects on longitudinal versus circular smooth muscle. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1500–1505. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.018556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Root B, Abrassart J, Myers DA, Monau T, Ducsay CA. Expression and distribution of glucocorticoid receptors in the ovine fetal adrenal cortex: effect of long-term hypoxia. Reprod Sci. 2008;15:517–528. doi: 10.1177/1933719107311782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ducsay CA, Hyatt K, Mlynarczyk M, Root BK, Kaushal KM, Myers DA. Long-term hypoxia modulates expression of key genes regulating adrenomedullary function in the late gestation ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1997–R2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00313.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ignarro LJ. Biosynthesis and metabolism of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. AnnuRevPharmacolToxicol. 1990;30:535–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.30.040190.002535. 535–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsubaki M, Hiwatashi A, Ichikawa Y, Hori H. Electron paramagnetic resonance study of ferrous cytochrome P-450scc-nitric oxide complexes: effects of cholesterol and its analogues. Biochemistry. 1987;26:4527–4534. doi: 10.1021/bi00388a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson JK, Moran F, Conley AJ, Bird IM. Zonal expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in sheep and rhesus adrenal cortex. Endocrinology. 2001;142:5351–5363. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.12.8537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Voorhis BJ, Dunn MS, Snyder GD, Weiner CP. Nitric oxide: an autocrine regulator of human granulosa-luteal cell steroidogenesis. Endocrinology. 1994;135:1799–1806. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.5.7525252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams ML, Nock B, Truong R, Cicero TJ. Nitric oxide control of steroidogenesis: endocrine effects of NG-nitro-L-arginine and comparisons to alcohol. Life Sci. 1992;50:PL35–PL40. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kishimoto J, Tsuchiya T, Emson PC, Nakayama Y. Immobilization-induced stress activates neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) mRNA and protein in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in rats. Brain Res. 1996;720:159–171. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Natarajan R, Lanting L, Bai W, Bravo EL, Nadler J. The role of nitric oxide in the regulation of aldosterone synthesis by adrenal glomerulosa cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;61:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(97)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cymeryng CB, Lotito SP, Colonna C, et al. Expression of nitric oxide synthases in rat adrenal zona fasciculata cells. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1235–1242. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonzales GF, Chung FA, Miranda S, et al. Heart mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase is upregulated in male rats exposed to high altitude (4,340 m) Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2568–H2573. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00812.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valdez LB, Zaobornyj T, Alvarez S, Bustamante J, Costa LE, Boveris A. Heart mitochondrial nitric oxidesynthase. Effects of hypoxia and aging. Mol Aspects Med. 2004;25:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Justice JM, Tanner MA, Myers PR. Endothelial cell regulation of nitric oxide production during hypoxia in coronary microvessels and epicardial arteries. JCell Physiol. 2000;182:359–365. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<359::AID-JCP6>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murata T, Sato K, Hori M, Ozaki H, Karaki H. Decreased endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) activity resulting from abnormal interaction between eNOS and its regulatory proteins in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. JBiolChem. 2002;277:44085–44092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murata T, Yamawaki H, Hori M, Sato K, Ozaki H, Karaki H. Hypoxia impairs endothelium-dependent relaxation in organ cultured pulmonary artery. EurJPharmacol. 2001;421:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson LP, Dong Y. Chronic hypoxia decreases endothelial nitric oxide synthase protein expression in fetal guinea pig hearts. JSocGynecolInvestig. 2005;12:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chicoine LG, Avitia JW, Deen C, Nelin LD, Earley S, Walker BR. Developmental differences in pulmonary eNOS expression in response to chronic hypoxia in the rat. JApplPhysiol. 2002;93:311–318. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01083.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buga GM, Griscavage JM, Rogers NE, Ignarro LJ. Negative feedback regulation of endothelial cell function by nitric oxide. Circ Res. 1993;73:808–812. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]