Abstract

Lithium (Li+) has been used to treat mood affect disorders, including bipolar, for decades. This drug is neuroprotective and has several identified molecular targets. However, it has a narrow therapeutic range and the one or more underlying mechanisms of its therapeutic action are not understood. Here we describe a pharmacogenetic study of Li+ in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Exposure to Li+ at clinically relevant concentrations throughout adulthood increases survival during normal aging (up to 46% median increase). Longevity is extended via a novel mechanism with altered expression of genes encoding nucleosome-associated functions. Li+ treatment results in reduced expression of the worm ortholog of LSD-1 (T08D10.2), a histone demethylase; knockdown by RNA interference of T08D10.2 is sufficient to extend longevity (~25% median increase), suggesting Li+ regulates survival by modulating histone methylation and chromatin structure.

Genetic studies of lifespan determination have revealed a large number of potential targets for chemical compounds to slow aging. Because aging is a major risk factor in human disease, such compounds may prove useful in postponing age-related diseases. A number of compounds have been shown to extend lifespan of simple animals such as the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. These range from compounds with known antioxidant activities such as the superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics EUK-8 and EUK-134 (1–3), through to compounds that appear to act through modulation of neural activity (4) such as the anticonvulsants ethosuximide, trimethadione, and 3,3-diethyl-2-pyrrolidinone. Some natural products are also associated with lifespan extension, including the polyphenol resveratrol, which increases lifespan in yeast (5), C. elegans, and the fly Drosophila melanogaster (6).

The alkali metal ion Li+ affects diverse biological processes, from a range of developmental effects in simple metazoans to metabolic alterations in mammals (7). Despite its clinical use (8,9), the mechanism of action in the brain still remains unclear (10). However, several molecular targets have been identified, including inositol monophosphatase and phosphomonoesterases (11), sodium coupled citrate transporter (12), and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β)4 (7).

Li+ has neuroprotective effects; in rats, Li+ treatment results in an elevation in bcl-2 levels in several brain regions (13, 14). The C. elegans ortholog of this neuroprotective protein (CED-9) (15) functions to prevent cell death during development (16, 17). In models of neurological disease, Li+ has been shown to reverse axon transport deficiencies in transgenic Drosophila (18) and reduce insoluble tau (19), abrogate axonal degeneration (20), and decrease β-amyloid production in mice (21). In studies on cultured cerebellar granule cells of rats, Li+ protected against apoptosis induced by anticonvulsants (22). Li+ protects cells in models of Huntington disease (HD) (23) and against toxicity caused by aggregate-prone proteins containing either polyglutamine or polyalanine expansions in Drosophila (24). Li+ can also improve neurological function and pathology in a Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1 mouse model (25). Recently, Li+ was shown to protect C. elegans from the toxic effects of expression of a fragment of huntingtin protein containing an expanded polyglutamine tract associated with human HD (26).

To understand the mechanisms of Li+ action we have taken a pharmacogenetic approach in the C. elegans. Not only does this allow mediators of Li+ action to be identified, but it also allows for an assessment of the general effects of the drug in a whole organism.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains

Bristol N2: wild-type, CB4876: clk-1(e2519), CF1038: daf-16(mu86), DA465: eat-2(ad465), DR1572: daf-2(e1368), MT3970: mab-5(mv114) ced-9(n1653), SS104: glp-4(bn2), TJ356: zIs356 (Ex(daf-16::gfp+rol-6)), TJ1060: spe-9(hc88); fer-15(b26), VC199: sir-2.1(ok434), WM104: unc-101(sy216) gsk-3(nr2047)/hIn1(unc-54(h1040)) and NL2099: rrf-3(pk1426) were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center at the University of Minnesota. Worms were cultured on 6-cm nematode growth media (NGM) agar plates on a lawn of live Escherichia coli OP50 and maintained at 20 °C unless otherwise stated. All experiments were performed with hermaphrodite worms.

Lifespan Assay

All populations were cultured at 20 °C for 3 days until reaching the L4 larval stage, except glp-4(bn2), which was cultured at the permissive temperature of 16 °C, and then shifted to 25 °C as eggs for the lifespan assay. Populations of L4-stage worms were then transferred onto NGM plates with or without LiCl (Sigma) as specified and subsequently maintained at 25 °C. Populations were examined every 1–2 days and transferred onto new plates to avoid starvation or larval crowding as required. Death events were noted as a failure to respond to touch with a platinum wire and animals lost or that died from internal larval hatching were recorded as censored data as previously described (27).

Fertility Assay

A synchronous wild-type hermaphrodites were cultured at 20 °C for 3 days until they reached the L4 stage. 15 individual worms were then transferred and maintained each on a separate NGM plate with or without 10 mm LiCl and cultured at 25 °C. Individuals were transferred daily; the progeny were left to develop for 3 days before counting.

Elemental Analysis

Approximately 1 × 106 C. elegans eggs were collected following hypochlorite treatment and hatched overnight in S-basal to synchronize development. All cultures were maintained at 20 °C. Larvae developed for 3 days and were then collected and washed with S-basal in 15-ml polypropylene tubes (Corning). 50,000 adults were transferred onto 10-cm NGM plates with or without 10 mm LiCl, and the mixture was incubated for 24 h at 25 °C. All plates had ~ 1 ml of 2×1011 cells (OP50)/ml as a food source. Populations were then collected with 10 ml of S-basal and filtered through 40-µm nylon cell strainers (BD Falcon) and washed with 200 ml of 18 MΩ milli-Q H2O (Millipore). Worms were transferred to 15-ml tubes and pelleted by brief centrifugation. Elemental analysis was then conducted using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP) as previously described (28). The ICP was routinely calibrated using National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)-traceable elemental standards (Sigma-Aldrich) and validated using NIST-traceable test standards (sample 1577b, NIST); all ICP reagents and plastic ware were company-certified and routinely tested for trace metal work. Values shown are the averages of four replicates normalized by weight for growth media and by organism number for worms.

Microarray Analysis

Gene expression data were collected using wild-type (N2 strain) nematodes comparing six untreated (control) populations to a common mixed stage reference RNA and six populations treated with 10 mm LCl for 48 h at 25 °C. All populations were initially cultured at 20 °C for 3 days from eggs until reaching the L4 stage and were then transferred onto media with and without LiCl. Each biological replicate was comprised of total RNA extracted from 50 nematodes using an Absolute RNA Microprep Kit (Stratagene). Sample integrity and concentration were determined using a ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanodropTechnologies) and Bioanalyzer Pico Chip (Agilent Inc.). Total RNA samples were then amplified using Amino Allyl Message Amplification II Kit (Ambion Inc.), using ~ 500 ng of Total RNA. Sample integrity and concentration was again determined using a ND-1000 Spectrophotometer and Bioanalyzer Pico Chip. AmplifiedRNAwas then labeled using CyDye Post Labeling Reactive Dyes (Cy3 and Cy5, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp.) in conjunction with the reagents and protocol from the Amino Allyl Message Amplification II Kit. To improve hybridization the amplified RNA was “fragmented” using an RNA Fragmentation kit (Ambion Inc.). Hybridization was done using a Lucidea Slide Pro machine (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp.) using the manufacturer’s protocol. All wash solutions (Nuclease-free Water, 20% SDS and 20× SSC) were obtained from Ambion Inc. The arrays were obtained from the Washington University in St. Louis Genomic Sequencing Center. Arrays were scanned using a Scan Array Express 2-Laser Scanner (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Images were then quantitated using the GenePix 5.1 software package (Molecular Devices Corp.) using GAL file overlays provided by the Washington University in St. Louis (Genomic Sequencing Center), and a GPR file was generated. All gene annotations were obtained from Wormbase (release WS161).

Statistics

Survival assays were analyzed using a non-parametric (Mantel-Haenszel) Log rank test and presented as Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Prism™ software package). Differences in fertility and elemental content were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t test (Excel MS).

To find differentially expressed genes in the microarray analysis, we performed two-sample t-tests for each gene and then used a FWER cut-off of 5% on the marginal p values using the Holm’s step-down method (29). Clusters of similarly expressed genes were found using the hierarchical modification of partitioning around medoids algorithm, called HOPACH (30), which also re-orders the data (in our case genes) for display in an ordered distance matrix.

Associations between gene ontology (GO) terms and responding transcripts were determined using the mean difference in the log2 expression of genes within each GO and all genes outside of each GO, respectively. This procedure was performed on all GOs with 25 or more constituent genes. Differentially expressed GOs were then identified using the same manner as described above, using raw p values derived from two sample t test and aFWERcut-off of 5% based on the slightly more conservative Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Mortality Analysis

Estimates of initial mortality rate and rate of increase with age and model fitting were made using WinModest (31). Gompertz mortality curves, ln(ux) = ln(a) + bx, where ux defines the age-specific hazard, were fitted with log-likelihood ratios used to examined the effects of constraining the intercept (a) or gradient (b) variables (31).

Cell Culture and Immunochemical Analysis

Human breast cancer cell line MCF7 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Mediatech) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Mediatech), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Mediatech), and 10 µg/ml insulin (Sigma). On 10-cm dishes, 1 × 106 cells were plated in normal media, attachment and grown for 24 h, and then treatment with LiCl for 48 or 72 h as indicated prior to fractionation and extract preparation. Cells were lysed in 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, 10 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.3% IGEPAL, and one Complete, Mini, EDTA-free; Protease Inhibitor Mixture tablet (Roche) per 10 ml of lysis buffer, with a Dounce homogenizer. Nuclei were pelleted with a 5000 rpm spin for 5 min, and then lysed with 100 µl of 100 mm NaCl, 25 mm Tris, pH 7.5, and 2% SDS, with 4 × 10 s pulses of sonic disruption on ice. Standard SDS-PAGE and immunodetection protocols were used with rabbit anti-LSD1 (Abcam) and anti-Lamin A/C (Cell Signaling Technologies).

RESULTS

Lifespan of C. elegans Exposed to LiCl

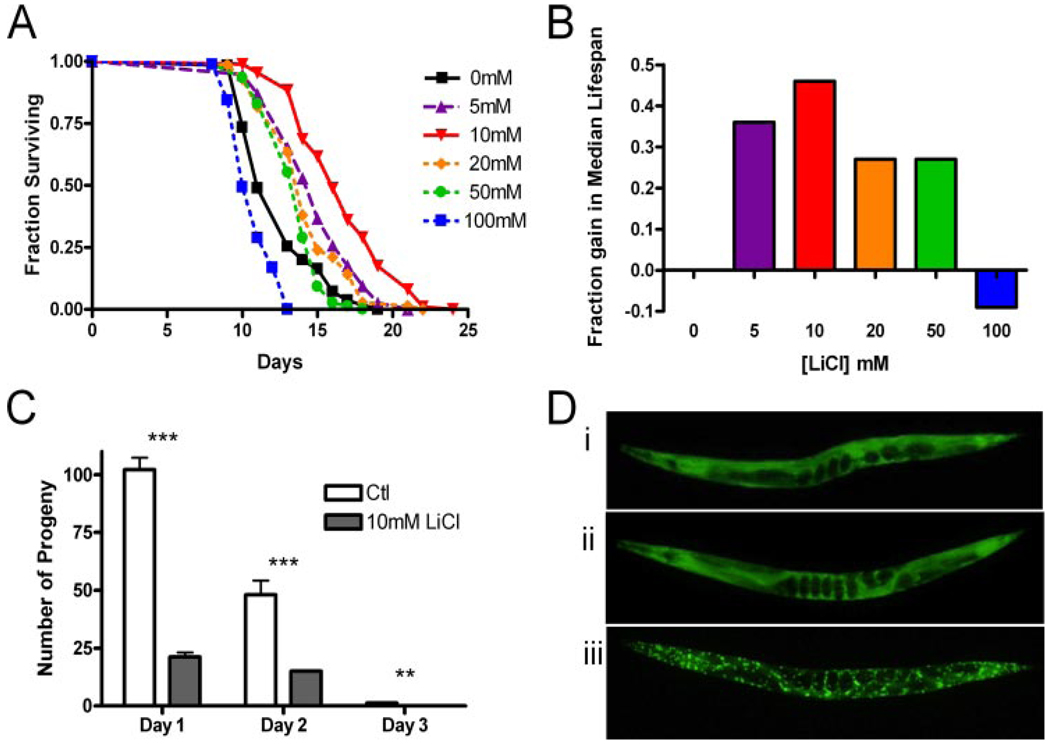

Cohorts of pre-fertile wild-type worms were exposed to LiCl over a concentration range of 5–100 mm following development. Chronic LiCl treatment significantly increased both median and maximum lifespan (Fig. 1, A and B). A dose-response relationship was observed with an optimal lifespan increase seen at 10 mm LiCl where median wild-type lifespan was increased by 46% (p < 0.0001). Some degree of variability in the extent of lifespan extension was observed; across all replicates the average median lifespan increase was 36% (Table 1).

FIGURE 1. Effects of LiCl on wild-type C. elegans lifespan and fertility.

A, Kaplan-Meier survival curves of hermaphrodite worm populations exposed to 0–100 mm LiCl. B, fraction gain in median survival (days) of wild-type populations cultured on 0–100 mm LiCl. C, effects of 10 mm LiCl on wild-type C. elegans fertility at 25 °C. All data presented as mean ± S.E. **, p < 0 01; ***, p < 0.001. D, a 24-h exposure to 10 mm LiCl has no effect on DAF-16 nuclear localization. Fluorescence micrographs of DAF-16::GFP expression in 4-dayold animals. Untreated control animal (i) and individuals given a 24-h exposure to 10 mm LiCl (ii) and a 2h 33 °C heat shock (iii).

TABLE 1. Lifespan effects at 25 °C of post-developmental exposure to 10mm LiCl.

Median life-span (LS) in days at 25 °C of populations treated with (+) or without (−) 10 mm LiCl. Genotype with no drug are compared with line 1, with percentage change in median LS due to genotype (gt) shown but not compared for statistical difference. Percentage changes in median LS due to Li+ are based on comparisons are against the same genotype with no drug treatment. n is the number of hermaphrodites examined, with the number of censored animals shown in parentheses. “Replicates” indicates the number of independent experiments.

| Genotype | LiCl | Median LS |

Median increase (gt) |

Median increase (Li+) |

n | Replicates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ||||||

| Wild type | − | 10.6 | 922 (94) | 11 | ||

| + | 14.5a | +36% | 1141 (29) | |||

| gsk-3β(nr2047)b | − | 7.0a | −36% | 156 (9) | 2 | |

| + | 6.5c | −7% | 147 (13) | |||

| eat-2(ad465) | − | 12.0 | +9% | 94 (13) | 2 | |

| + | 16.0a | +33% | 206 (21) | |||

| clk-1(e2519) | − | 13.0 | +18% | 166 (22) | 2 | |

| + | 17.5a | +35% | 190 (7) | |||

| daf-2(e1368) | − | 14.0 | +27% | 143 (19) | 2 | |

| + | 17.0a | +21% | 146 (11) | |||

| daf-16(mu86) | − | 9.5 | −14% | 145 (3) | 2 | |

| + | 13.5a | +50% | 119 (17) | |||

| sir-2.1(ok434) | − | 15.0 | +36% | 168 (25) | 2 | |

| + | 18.0a | +20% | 184 (3) | |||

| glp-4(bn2) | − | 13.5 | +23% | 201 (0) | 2 | |

| + | 16.5a | +22% | 212 (0) | |||

| ced-9(n1653)d | − | 8.5 | −23% | 213 (83) | 2 | |

| + | 15.0a | +76% | 199 (70) | |||

| spe-9(hc88); | − | 13 | NAe | 112 (10) | 1 | |

| fer-15(b26) | + | 17a | +31% | 120 (1) | ||

p < 0.0001.

Mutant in a unc-101(m1) genetic background.

p < 0.01.

Mutant in a mab-5(mv114) genetic background.

NA, not applicable.

To determine if lifespan extension was associated with increased intracellular Li+ concentrations, ICP was used to measure the elemental content of nematode populations. In control groups, Li+ was below detection limits (0.45 pmol per worm), whereas in those exposed to 10 mm LiCl for 24 h an average of 6 pmol of Li+ per worm was detected (supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Four-day-old wild-type worms have an approximate volume of 5 nl (32); assuming homogenous distribution of Li+ throughout the worm, we estimate the concentration of Li+ to be ~ 1.2 mm. This concentration falls within the therapeutic range for serum concentration used to treat bipolar disorder thus C. elegans treated with 10 mm LiCl could provide a physiologically appropriate model of human treatment regimens (9). This finding is consistent with the view that elevated intracellular Li+ is responsible for the observed lifespan extension.

Fertility Effects of LiCl

Given the wide variety of potential targets of Li+, toxicity was expected at high concentrations. Consistent with this, median worm lifespan was significantly shortened by 9% when they were exposed to 100 mm LiCl (p < 0.001; Fig. 1, A and B). In addition, Li+ had a detrimental effect on hermaphrodite self-fertility (Fig. 1C). Mean total progeny production at 25 °C for unmated, untreated hermaphrodites was 148.4 ± 7.1 (S.E.), whereas 10 mm LiCl treated worms produced only 22.2 ± 2.2 (S.E.; p < 0.0001). Li+-treated worms produced less eggs, and most eggs that were laid subsequently failed to hatch.

Epistatic Interaction with Known Li+ Target, GSK-3β

We then took a pharmacogenetic approach to understanding the mechanism of lifespan extension by Li+. Here we combine Li+ treatment with the effects of specific single-gene mutations in known targets of Li+ or in genes known to modulate aging rate. We first examined whether Li+ extends lifespan through inhibition of the known target GSK-3β using a maternally rescued null gsk-3β(nr2047) mutant. A 36% reduction in median lifespan in gsk-3β(nr2047) mutants was observed compared with wild type (p < 0.0001, Table 1). Mutational loss of GSK-3β appears detrimental to lifespan. This observation is inconsistent with the model of Li+-induced lifespan extension exclusively through inhibition of GSK-3β activity. Exposure of gsk-3β(nr2047) mutants to Li+ causes a further, but slight 7% decrease in median lifespan (p < 0.001). Therefore, although inhibition of GSK-3β is not sufficient for lifespan extension, lifespan extension by Li+ actually requires GSK-3β.

Epistatic Interaction with Caloric Restriction

Caloric restriction (CR) is associated with lifespan extension in a range of species (33). We considered the possibility that Li+ induced caloric restriction by causing an aversion to the E. coli food source that takes the form of a circular lawn centered on the NGM plate. The Li+ was homogenously dispersed through the media and caused no observable alteration in the distribution of the worms. Furthermore, C. elegans are actually attracted to Li+ on agar plates (34). However, we examined the possibility that Li+ may act as a CR mimetic by reducing food intake or acting on signaling pathways or other downstream effectors of CR. We tested this hypothesis by asking whether Li+ could extend the lifespan of CR worms. EAT-2 is a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit required for pharyngeal pumping (35). Worms with mutations of eat-2 exhibit slowed feeding rates and extended lifespan (36) and is thus thought to mimic CR. It has also been suggested that mutation of the clk-1 gene extends lifespan by a mechanism similar to CR. The clk-1 mutant worms have altered ubiquinone biosynthesis and extend lifespan by a mechanism related to CR (37). We observed that Li+ treatment extends the median lifespan of both eat-2 and clk-1 mutants (33 and 35%, p < 0.0001, respectively; Table 1). There are a number of interpretations of this finding. It is possible that each of these single gene mutation do not produce the maximum CR-associated lifespan extension, therefore Li+ treatment further increases the CR action. However, because the magnitude of the lifespan extension is similar to that observed in wild-type worms, the data is more consistent with a model in which CR and Li+ treatment extend lifespan by distinctive mechanisms.

Epistatic Interaction with the IGF/FOXO Signaling Pathway

Another well characterized influence on C. elegans lifespan is that of an IGF/FOXO signaling pathway that regulates the activity of the FOXO-like transcription factor DAF-16. The daf-2 gene encodes an insulin-like receptor protein, and hypomorphic mutations can result in a doubling of lifespan (38). Li+ extended daf-2(e1368) median lifespan by 19% (Table 1). This could suggest an independent mechanism, but the magnitude of lifespan extension is somewhat smaller than that observed in wild-type worms. Lifespan extension by the daf-2(e1368) mutation requires the integrity of DAF-16; worms carrying mutations in both daf-2 and daf-16 exhibit normal lifespans. To further assess the role of the IGF/FOXO signaling pathway in Li+-induced lifespan extension, we tested the effect of Li+ on daf-16(mu86) worms, which lack functional DAF-16, and observed a 50% increase in median lifespan (p < 0.0001, Table 1). This strongly suggests that Li+ does not affect lifespan through the insulin signaling pathway. This was further supported by two other observations. Overexpression of SIR-2, an NAD-dependent deacetylase, extends C. elegans lifespan (39), potentially via interactions with DAF-16 (40). We find Li+ increases median lifespan of sir-2.1 null mutants, consistent with observation that Li+ affects longevity independently from the IGF/FOXO pathway. In addition, we treated worms expressing a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged DAF-16 (TJ356: zIs356 (Ex(daf-16::gfp+rol-6))). The DAF-16::GFP protein is located in the nucleus in daf-2 mutants or during stress (41). When we exposed worms expressing this fusion protein to 10 mm LiCl, we observed no nuclear localization (Fig. 1D). We conclude that the effect of Li+ on lifespan is not due to reduced IGF/FOXO signaling.

Epistatic Interaction with Germ Line Signaling

Genetic or laser ablation of germ line precursor cells is an additional mechanism in C. elegans to extend lifespan (42). Worms carrying the glp-4(bn2) allele are sterile when allowed to develop at 25 °C essentially lacking germ line proliferation (43). The lowered fertility of Li+-treated worms prompted us to consider that Li+ could extend lifespan by inhibiting germ line proliferation or function. However, we found that Li+-treated glp-4(bn2) mutants were even longer lived than the untreated mutants (22%, p < 0.0001; Table 1). This is consistent with Li+ affecting lifespan independently of germ line effects on lifespan.

Epistatic Interaction with ced-9/bcl-2

We also considered whether Li+ could be acting through other mechanisms previously described as possible targets in mammalian systems. In rats, Li+ treatment results in an elevation in bcl-2 levels in several brain regions (13, 14). Similar increases have been reported in Li+-treated human cells. The rise in bcl-2 levels might explain the lifespan effects of Li+ due to the clear neuroprotective role of this protein (15). The C. elegans ortholog of bcl-2 (CED-9) functions to prevent cell death during development (16, 17). To ask whether Li+ lifespan effects were dependent on CED-9 function, we treated worms carrying the ced-9(n1653) loss-of-function mutation (16) and observed a 78% increase in median lifespan (p < 0.0001, Table 1). The lack of involvement of CED-9 anti-apoptotic processes is consistent with the postmitotic status of adult C. elegans and the preservation of the C. elegans nervous system of C. elegans during normal wild-type aging (44).

Genome-wide Transcript Response to LiCl

To further investigate the biological action of Li+ we performed an unbiased examination of the mRNA abundance changes as a result of exposure to 10 mm LiCl, using a full genome microarray study. Differentially expressed genes were identified through t-tests via comparing populations of control versus Li+-treated worms. Using a false discovery rate (45) of ≤ 0.01, we observed 702 changes in gene expression. We then imposed a stringent FWER (29) of ≤0.05, reducing our list to 99 genes. We identified 65 up-regulated and 34 down-regulated transcripts, which were then sorted by geometric mean ratio and are shown in supplemental Table S3. These genes were also clustered using a hierarchical clustering routine (HOPACH) to find possible coregulated suites of genes (30). We observed 9 distinct clusters, as shown in an ordered distance matrix (supplemental Fig. S1). Gene expression variation across all chips for both treatments was plotted with the medoid values (supplemental Fig. S2). We then performed an analysis at the GO level to identify common function of responding genes. We identified five significant GOs (at a FWER cut-off of 0.05) associated with Li+ treatment (supplemental Table S4), including nucleosome and nucleosome assembly-associated genes that are significantly over-represented in response to Li+ treatment. Validation of a subset of transcripts identified as differentially expressed following Li+ treatment was performed using quantitative reverser transcription-PCR (supplemental Table S5).

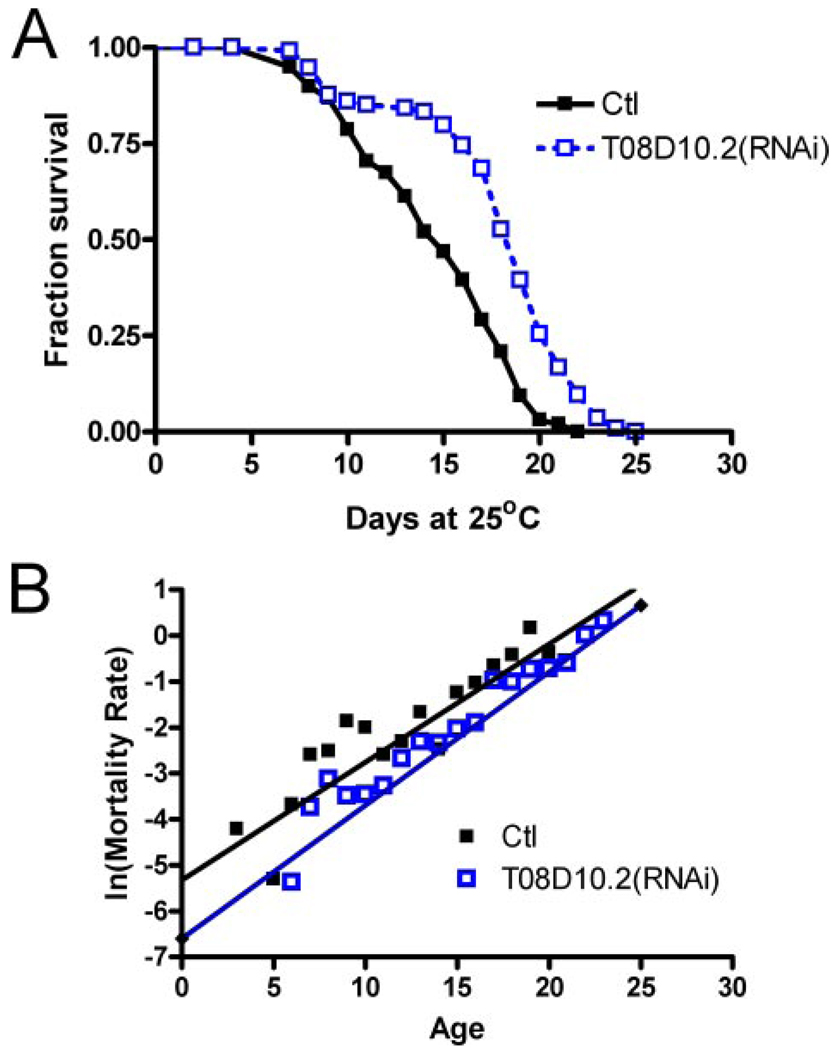

C. elegans LSD-1 Ortholog

Following the identification of the nucleosome and nucleosome assembly-associated GO we decided to more closely examine potential nucleosome regulators from our list of affected transcripts. We observed that transcripts for T08D10.2, an amine oxidase and worm ortholog of human LSD-1, are reduced to 0.33 that of controls following Li+ treatment (supplemental Table S3, part i). LSD-1 encodes a histone demethylase (46). Treating an RNAi-sensitive genetic background, rrf-3(pk1426) (47) ,with T08D10.2(RNAi) during adulthood resulted in an average median lifespan increase of ~26% (p < 0.001; Fig. 2A). Demographic analysis suggests that the rate of increase in the age-specific mortality rate with age was not significantly altered, but the increase was shifted to a later age (p < 0.01, Fig. 2B). This effect is consistent with a delay in the onset of aging or lowered intrinsic mortality, suggesting that chromatin remodeling may be a component of aging in C. elegans.

FIGURE 2. Effects of T08D10.2(RNAi) on C. elegans lifespan.

A, Kaplan-Meier survival curve showing median lifespan of 15 days (control) versus 19 days for T08D10.2(RNAi), p < 0.001. B, log-linear plot of mortality rate versus age shown for control and T08D10.2(RNAi)-treated C. elegans. Gompertz curves were fitted, and the mortality rate increase was found not to be different; however, a significant difference in initial mortality rate (p < 0.01) is consistent with a shift of the mortality curve to later ages following T08D10.2(RNAi).

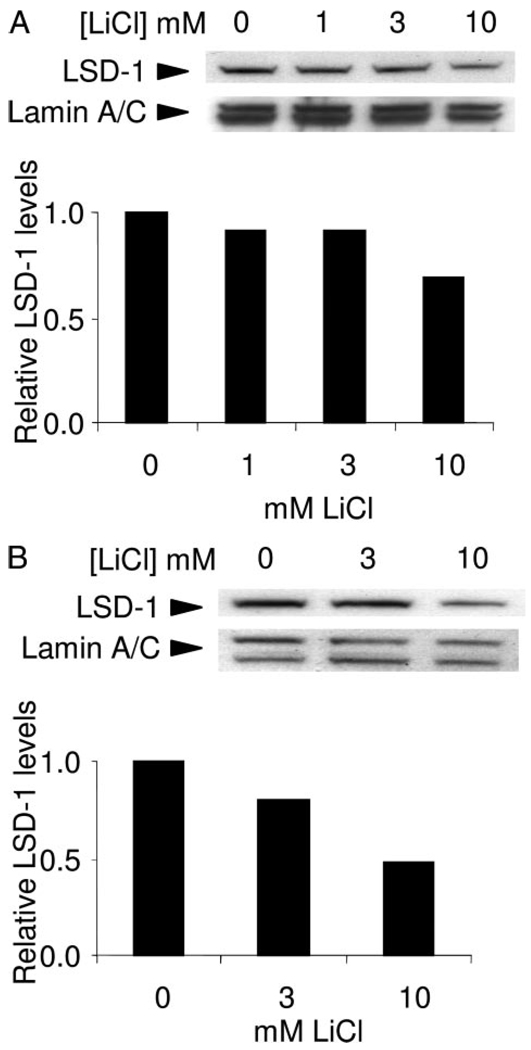

Effects of LiCl in Mammalian Cells

Genetic effect on aging appears to be conserved across a wide variety of species, which is probably the result selection on early life fitness traits such as development, fertility, and stress resistance. This raises the possibility that chemical compounds that alter lifespan in simple organisms may also affect aging in mammals. If LSD-1 is an important target of Li+ in C. elegans then we wish to know whether the mammalian LSD-1 is also down-regulated a mammalian cell line. To determine the conservation of effects by Li+ we treated human breast cancer cell line MCF7 with LiCl and measured the levels of LSD-1 (Fig. 3, A and B). We found that LSD-1 responded to chronic exposure to Li+, with an approximate 50% reduction after 72-h exposure to 10 mm LiCl compared with untreated controls. These results are consistent with Li+ affecting LSD-1 in mammalian cells and tissues and may be capable of causing chromatin modification.

FIGURE 3. LiCl reduces Lsd-1 levels in MCF7 cells.

Immunoblot showing reduced LSD-1 levels following 48-h (A)and 72-h (B) exposure to the LiCl concentrations shown. LSD-1 levels shown are relative to untreated controls following a correction for loading differences using Lamin A/C levels.

DISCUSSION

This study highlights the utility of C. elegans for pharmacogenetic analysis of drug activity and raises the possibility that a drug in current use could have effects on human aging phenotypes. This is especially true because the amount of Li+ within treated nematodes measured using ICP falls close to recommended therapeutic plasma levels (9).

An epistatic analysis between Li+ and mutations in genes already known to alter aging in C. elegans revealed that none of these genes were required for the effect of Li+ on longevity, suggesting we have identified a novel mechanism capable of modulating aging. The one gene activity essential was GSK-3β. GSK-3β is inhibited by Li+ directly by competing with magnesium, a required cofactor (48), and indirectly by increasing Ser-9 phosphorylation via an unknown mechanism (49, 50). Maternally rescued gsk-3β null C. elegans have decreased lifespan and show no Li+-induced increase in lifespan (Table 1). This implies that GSK-3β is required for Li+ action. This result is somewhat counterintuitive and may be explained by two reasons. Firstly, this may represent a threshold effect, such that reduced adult GSK-3β may have different effects compared with a complete absence of GSK-3β activity. Secondly, inhibition of GSK-3β activity may have differing effects in different tissues. In C. elegans intestinal cells GSK-3β inhibits SKN-1, a transcription factor that induces phase II detoxification genes, oxidative stress responses, and is required for longevity (51). Inhibition of GSK-3β via Li+ in these intestinal cells may derepress SKN-1 and potentially increase oxidative stress responses and modulate aging. However, reduced GSK-3β activity in other adult tissues may be detrimental; for example, we have recently identified neuronal GSK-3β as a potent pro-longevity factor.5 The complete inhibition of GSK-3β activity in all tissues may have conflicting effects on aging.

Array analysis of transcripts responding to Li+ revealed many changes, including ABC transporters with up-regulation of pgp-5 and pgp-6, and down-regulation of ced-7 (supplemental Table S3). The former genes are part of a P-glycoprotein subclass of the ATP-binding cassette transporters, which are highly conserved and dynamically evolving (52). The P-glycoproteins encoded by pgp-5 and -6 are expressed in the intestinal cells (53) and are predicted to function as efflux pumps that protecting C. elegans by exporting exogenous toxins. pgp-6 is also expressed in adult amphid sensory neurons (53). Interestingly, P-glycoproteins are also a component of the blood-brain barrier in vertebrates, suggesting that Li+ may alter transport of toxic compounds from the vertebrate brain if these effects are conserved. In contrast, transcript for ced-7 is down-regulated (supplemental Table S3). Mutant alleles of ced-7 mutants are defective in engulfment of the cell corpses during apoptosis (54).

We also observed elevated levels of mRNAs encoding ten histones (supplemental Table S3) in response to Li+. Of these, nine are identified as replication-dependent histones (his-4, -7, -8, -45, -61, -62, -64, -67, and -68), involved in maintaining regular chromatin structure during replication of nuclear DNA (55). The remainder is a replacement histone (his-35) and is thought to be expressed constitutively or in a tissue-specific manner. These results are consistent with Li+ causing changes in nucleosome composition and remodeling of chromatin. These results may also indicate Li+ causing some attempt to initiate DNA replication or repair. The nematodes exposed to Li+ were late L4 larvae (3 days old) when essentially all somatic cells are non-dividing (56), although endoreduplication of nuclear DNA is observed within a limited number of hypodermal cells (57). However, analysis of bromodeoxyuridine incorporation to identify cells undergoing DNA replication revealed no differences between untreated and Li+-treated worms (data not shown). The effect on histone mRNAs may have originated from perturbation of developing embryos in utero, because 10 mm LiCl was clearly detrimental to early development (Fig. 1C).

However, we propose that Li+ may have other chromatin effects particular to adult tissues. In response to Li+ transcript for T08D10.2, the worm ortholog for Lsd-1, was reduced 3-fold. In MCF7 human breast cancer cells Li+ also reduced LSD-1 protein levels to approximately one-half that of untreated controls, suggesting this effect of Li+ may be broadly conserved. LSD-1 acts as a histone demethylase to remodel chromatin (46). Chromatin is composed of dynamic nucleosomes that regulate the DNA-dependent processes of transcription, replication, recombination, and repair (58). The core of four histone proteins that form nucleosomes is subject to an epigenetic code of post-translational modifications (59). The combination of these modifications and the recruitment of particular co-factors then determine the “openness” of chromatin domains and ability of this region of DNA to function. The regulation of gene silencing by chromatin modification is a proposed determinant of organismal aging (60).

The process of normal aging is also intrinsically linked to late onset neurodegenerative diseases. However, the cellular 5 G. McColl and G. J. Lithgow, unpublished data. changes and events due to aging that impact neurodegeneration are not yet understood. In a screen for candidate therapeutic compounds in a C. elegans HD model, Li+ was shown to suppress HD neurotoxicity (26). Consistent with our longevity experiments the FOXO-like transcription factor DAF-16 was not required for this neuroprotective effect. These results suggest there may be a shared mechanism between protection against polyglutamine disease and extended lifespan.

Studies using HD models have also shown that mutant huntingtin expression leads to a change in histone acetyl transferase activity. This aberrant acetyltransferase activity and resulting chromatin remodeling may lead to transcriptional dysregulation and, ultimately, neuronal dysfunction in HD (61). Furthermore, a therapeutic role for histone deacetylase inhibitors in a number of HD models has been recently reported. In contrast, overexpression of C. elegans SIR-2.1, a deacetylases, extends longevity (39). However, a direct interaction between histones and SIR-2.1 remains to be shown. These results suggest that regulation of chromatin remodeling can affect neuroprotection from polyglutamine disease and modulate organismal aging.

In summary, we have identified a novel indirect target of Li+, LSD-1, and its effects on longevity. The molecular details of how Li+ alters survival via modulating histone methylation and chromatin structure require further study. However, C. elegans may be a useful model to dissect out these mechanisms. The use of simple model organisms with well developed genetics tools will expedite identification of molecular targets and signaling pathways affected by drug administration and thereby facilitate the development improved therapies for disease states and disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary K. Scott, Krysta Felkey, Lawreen Asuncion, Amanda Foster, and Michael Benedetti for technical assistance, and Nicole Jenkins, Silvestre Alavez, Aiden Leigh, and members of the Lithgow laboratory for helpful discussions. We also thank Y. Bei and C. Mello for the generous gift of the WM21 strain.

Footnotes

All microarray data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE8058. Gene expression studies were facilitated by a Nathan Shock award (P30AG025708). All other nematode strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Research Resources.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures,” Figs. S1 and S2, and Tables S1–S5.

Supported by the American Federation for Aging Research.

Supported by the Ellison Medical Research Foundation and NIH Grants AG24385 and AG18679.

Supported by NIH Grants AG21069, AG22868, and NS050789-01, the Ellison Medical Resarch Foundation, the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, the American Federation for Aging Research, the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation, and the Herbert Simon Family Medical Foundation.

The abbreviations used are: GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; IGF, insulin/insulin-like growth factor; FWER, family wise error rate; HD, Huntington disease; NGM, nematode growth media; ICP, inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy; CR, caloric restriction; GFP, green fluorescent protein; RNAi, RNA interference.

G. McColl and G. J. Lithgow, unpublished data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Melov S, Ravenscroft J, Malik S, Gill MS, Walker DW, Clayton PE, Wallace DC, Malfroy B, Doctrow SR, Lithgow GJ. Science. 2000;289:1567–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keaney M, Gems D. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:277–282. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampayo JN, Olsen A, Lithgow GJ. Aging Cell. 2003;2:319–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evason K, Huang C, Yamben I, Covey DF, Kornfeld K. Science. 2005;307:258–262. doi: 10.1126/science.1105299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, Zipkin RE, Chung P, Kisielewski A, Zhang LL, Scherer B, Sinclair DA. Nature. 2003;425:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, Sinclair D. Nature. 2004;430:686–689. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein PS, Melton DA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:8455–8459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cade JFJ. Med. J. Aust. 1949;2:349–352. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.06241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price LH, Heninger GR. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;331:591–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409013310907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phiel CJ, Klein PS. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001;41:789–813. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masuda CA, Xavier MA, Mattos KA, Galina A, Montero-Lomeli M. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:37794–37801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue K, Zhuang L, Maddox DM, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Biochem. J. 2003;374:21–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen RW, Chuang DM. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:6039–6042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen G, Zeng WZ, Yuan PX, Huang LD, Jiang YM, Zhao ZH, Manji HK. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:879–882. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.720879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hockenbery D, Nunez G, Milliman C, Schreiber RD, Korsmeyer SJ. Nature. 1990;348:334–336. doi: 10.1038/348334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hengartner MO, Ellis RE, Horvitz HR. Nature. 1992;356:494–499. doi: 10.1038/356494a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hengartner MO, Horvitz HR. Cell. 1994;76:665–676. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mudher A, Shepherd D, Newman TA, Mildren P, Jukes JP, Squire A, Mears A, Drummond JA, Berg S, MacKay D, Asuni AA, Bhat R, Lovestone S. Mol. Psychiatry. 2004;9:522–530. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez M, Hernandez F, Lim F, az-Nido J, Avila J. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:301–308. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noble W, Planel E, Zehr C, Olm V, Meyerson J, Suleman F, Gaynor K, Wang L, LaFrancois J, Feinstein B, Burns M, Krishnamurthy P, Wen Y, Bhat R, Lewis J, Dickson D, Duff K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:6990–6995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500466102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phiel CJ, Wilson CA, Lee VM, Klein PS. Nature. 2003;423:435–439. doi: 10.1038/nature01640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nonaka S, Katsube N, Chuang DM. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;286:539–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carmichael J, Sugars KL, Bao YP, Rubinsztein DC. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:33791–33798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berger Z, Ttofi EK, Michel CH, Pasco MY, Tenant S, Rubinsztein DC, O’Kane CJ. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:3003–3011. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watase K, Gatchel JR, Sun Y, Emamian E, Atkinson R, Richman R, Mizusawa H, Orr HT, Shaw C, Zoghbi HY. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voisine C, Varma H, Walker N, Bates EA, Stockwell BR, Hart AC. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McColl G, Vantipalli MC, Lithgow GJ. FASEB J. 2005;19:1716–1718. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2447fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Killilea DW, Atamna H, Liao C, Ames BN. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2003;5:507–516. doi: 10.1089/152308603770310158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holm S. Scand. J. Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Laan MJ, Pollard KS. J. Stat. Plan. Inf. 2003;117:275–303. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pletcher SD. J. Evol. Biol. 1999;12:430–439. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirose T, Nakano Y, Nagamatsu Y, Misumi T, Ohta H, Ohshima Y. Development. 2003;130:1089–1099. doi: 10.1242/dev.00330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bordone L, Guarente L. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;6:298–305. doi: 10.1038/nrm1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1973;70:817–821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKay JP, Raizen DM, Gottschalk A, Schafer WR, Avery L. Genetics. 2004;166:161–169. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.1.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakowski B, Hekimi S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:13091–13096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong A, Boutis P, Hekimi S. Genetics. 1995;139:1247–1259. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kenyon C. Cell. 2005;120:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L. Nature. 2001;410:227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berdichevsky A, Viswanathan M, Horvitz HR, Guarente L. Cell. 2006;125:1165–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henderson ST, Johnson TE. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1975–1980. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsin H, Kenyon C. Nature. 1999;399:362–366. doi: 10.1038/20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beanan MJ, Strome S. Development. 1992;116:755–766. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.3.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herndon LA, Schmeissner PJ, Dudaronek JM, Brown PA, Listner KM, Sakano Y, Paupard MC, Hall DH, Driscoll M. Nature. 2002;419:808–814. doi: 10.1038/nature01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y. Cell. 2004;119:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sijen T, Fleenor J, Simmer F, Thijssen KL, Parrish S, Timmons L, Plasterk RH, Fire A. Cell. 2001;107:465–476. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryves WJ, Harwood AJ. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;280:720–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Sarno P, Li X, Jope RS. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:1158–1164. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jope RS. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;24:441–443. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.An JH, Vranas K, Lucke M, Inoue H, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Blackwell TK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:16275–16280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508105102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheps JA, Ralph S, Zhao Z, Baillie DL, Ling V. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R15. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao Z, Sheps JA, Ling V, Fang LL, Baillie DL. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;344:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu YC, Horvitz HR. Cell. 1998;93:951–960. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pettitt J, Crombie C, Schumperli D, Muller B. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:857–866. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.4.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Dev. Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flemming AJ, Shen ZZ, Cunha A, Emmons SW, Leroi AM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:5285–5290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mellor J. Trends Genet. 2006;22:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peterson CL, Laniel MA. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R546–R551. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guarente L, Kenyon C. Nature. 2000;408:255–262. doi: 10.1038/35041700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sadri-Vakili G, Cha JH. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2006;2:330–338. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.