Abstract

Long-term pulse chase experiments previously identified a sizable population of BrdU-retaining cells within the renal papilla. The origin of these cells has been unclear, and in this work we test the hypothesis that they become quiescent early during the course of kidney development and organ growth. Indeed, we find that BrdU-retaining cells of the papilla can be labeled only by pulsing with BrdU from embryonic (E) day 11.25 to postnatal (P) day 7, the approximate period of kidney development in the mouse. BrdU signal in the cortex and outer medulla is rapidly diluted by cellular proliferation during embryonic development and juvenile growth, whereas cells within the papilla differentiate and exit the cell cycle during organogenesis. Indeed, by E17.5, little or no active proliferation can be seen in the distal papilla, indicating maturation of this structure in a distal-to-proximal manner during organogenesis. We conclude that BrdU-retaining cells of the papilla represent a population of cells that quiesce during embryonic development and localize within a region of the kidney that matures early. We therefore propose that selective papillary retention of BrdU arises through a combination of regionalized slowing of, and exit from, the cell cycle within the papilla during the period of ongoing kidney development, and extensive proliferative growth of the juvenile kidney resulting in dilution of BrdU below the detection level in extra-papillary regions.

Keywords: BrdU-retaining cells, renal stem cells, renal progenitor cells, kidney growth, kidney development

cells within tubules and interstitium of the renal papilla display adult stem cell characteristics such as BrdU retention and appear capable of forming structures resembling neurospheres in culture (11). Recent genetic labeling studies challenged the notion that the renal papilla is a significant intrinsic source of progenitor cells required for the repair process following acute kidney injury: genetic labeling studies convincingly show that injured nephrons are repopulated by cells arising within the nephron epithelium and that extensive proliferation of epithelial cells occurs in the nephron segment most severely damaged, the S3 segment of the proximal tubule (7). Thus, it seems unlikely that the distantly located yet intriguing BrdU-retaining cells within the papilla are a dedicated stem cell population. In this study, we test the hypothesis that these cells instead are labeled during embryonic development and sequestered in a compartment of the kidney with minimal cellular turnover. We find that BrdU-retaining cells of the papilla can be labeled only by pulsing with BrdU during the period of active kidney development in the mouse. Furthermore, BrdU signal in the cortex and outer medulla is rapidly diluted during embryonic development and subsequent growth of the kidney, whereas signal in the papilla is not. We conclude that BrdU-retaining cells of the papilla indeed do represent a population of cells that quiesce during embryonic development and localize within a region of the kidney with minimal cellular turnover.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BrdU labeling.

Animal care in accordance with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Maine Medical Center. All mice used in the study were of ICR outbred stock. For embryonic BrdU-labeling studies, noon on the day of the vaginal plug was counted as embryonic (E) day 0.5. BrdU crystals (Roche 10280879001) were dissolved in DPBS without calcium and magnesium to make a 10 mg/ml stock. This stock was used for all BrdU injections. For the embryonic time points (E10, E11, E14, and E17) in long-term retention studies, pregnant dams were injected intraperitoneally with two doses of BrdU (80 μg/g), one dose 8 h before the desired time point and one dose 8 h after (for example, injected at E9.75 and E10.25 for the E10 time point). For the postnatal (P) time points (P2, P3, and P12), the pups were injected with two doses of BrdU (80 μg/g), one 8 h before the time point and one 8 h after the time point. Kidney papillas were removed for immunostaining at 3 mo. For the short-term retention study, dams were injected with a single pulse of BrdU (80 μg/g) at E11.25 or E17.25, embryonic kidneys were harvested at E11.75, E14.5, E17.5, P3, and P28 for immunostaining. To examine proliferation in regions of the kidney, pups were injected with BrdU (80 μg/g) once daily for 1 wk (P7-P14, P14-P21, or P21-P28) and kidneys were harvested for immunostaining.

Histology and immunostaining.

For all histology and immunostaining, the tissue was harvested and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C. For immunofluorescence, unfixed tissue was transferred to 30% sucrose in PBS and allowed to equilibrate overnight at 4°C. Tissue was frozen in OCT embedding compound and 5-μm sections were cut on a Leica cryostat. The sections were stained using a mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody (Roche 11170376001), Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen A-21124) secondary antibody, and DAPI (Invitrogen D1306) as a nuclear counterstain. Treatment with 2 N HCl was necessary to make the incorporated BrdU available to the primary antibody. For immunohistochemical staining, the tissue was transferred from paraformaldehyde to 70% ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm. Immunohistochemical BrdU staining was performed using the Zymed BrdU staining kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DBA staining was performed on adjacent sections as previously described (13).

Quantitation of immunostaining.

Micrographs were generated for each region of the kidney from three separate BrdU-treated animals; 2.8 million pixels was selected from each micrograph using the following criteria: 1) absence of tears in the section, 2) absence of large veins, and 3) presence of tissue in the entire area. Thus, the surface area of tissue analyzed from each region of the kidney was identical. Color information was removed from each image using Photoshop CS3 to subtract the hematoxylin staining, leaving immunostained nuclei. The number of nuclei in each sample was quantitated using Image J after thresholding, and a minimum of five contiguous pixels was required to register a positive nucleus. Comparison between manual counting and digital quantification revealed a close correlation. The quantification method is reported in detail in Supplemental Fig. 1 (the online version of this article contains supplemental data).

RESULTS

Long-term pulse chase with BrdU or [H3]thymidine has been used to identify adult stem cell populations (2, 8, 9). Such stem cells cycle extremely slowly, necessitating a pulse period of several days. Once incorporated, the label is retained until cells have gone through a sufficient number of cell cycles to dilute the label below the threshold for detection. In the case of BrdU-retaining cells of the renal papilla, a 3.5-day pulse followed by a 3-mo chase period identifies long-term BrdU-retaining cells in the renal papilla. As kidney development in the rodent is active until approximately 1 wk after birth (6), we reasoned that the BrdU pulse administered between P3 and P7 in the original work describing BrdU retention in the papilla (11) may be marking cells that are quiescing in the normal course of kidney development, rather than a dedicated stem cell population. To test this, we performed a series of BrdU pulses at stages before, during, and after the period of active kidney development in the mouse (Fig. 1). To improve temporal resolution in our study, we chose to administer BrdU on 1 day only, rather than over a 3.5-day period. No retaining cells can be found in the papilla following BrdU administration before (E10) or after (P12) kidney development, whereas retaining cells can be readily identified following administration of BrdU during active kidney development (E14 and P3). Thus, active development and/or growth during the pulse period is indeed required for labeling of the long-term BrdU-retaining cell population in the papilla.

Fig. 1.

Papilla cells quiesce during development of the metanephric kidney. A: scheme for BrdU treatments: animals were pulsed either before [embryonic (E) day 10], during [E14, postnatal (P) day 3], or after (P12) the period of active embryonic development of the permanent kidney. B: immunofluorescent detection of BrdU (red), with DAPI nuclear counterstain (blue) to detect BrdU-retaining cells in papillas of 3-mo-old animals. A BrdU pulse at E10 does not result in retention of labeled cells in the papilla at 3 mo of age, whereas pulse of cells at either E14 or P3 does. A BrdU pulse administered after the period of active kidney development (P12) does not lead to retention of labeled cells at 3 mo. Inset: enlargements of boxed areas in each panel show overlap of BrdU with DAPI, demonstrating nuclear localization of signal. Dashed line in E14.5 panel outlines the kidney papilla.

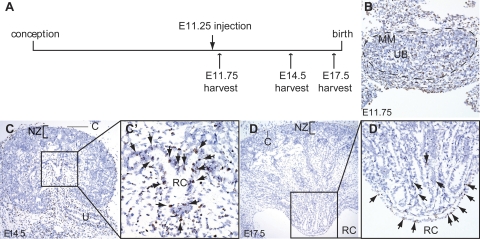

This intriguing finding indicates that BrdU-retaining cells localize to the papilla already during embryonic development. To better characterize this process, we performed a short-term pulse chase experiment, in which we examined the location of BrdU-labeled cells at embryonic time points following pulse at E11 (Fig. 2). We find that BrdU incorporation is almost ubiquitous in the E11.75 kidney after a BrdU pulse administered at E11.25 (Fig. 2B), but that labeled cells are localized to the central region of the kidney at E14.5, clustering around the nascent renal calyx (Fig. 2, C and C'). With the exception of the presumptive renal capsule, BrdU labeling has already been diluted out by cell division in the remainder of the kidney at this time point. At E17.5, a distinct renal papilla has developed, and BrdU-retaining cells are restricted to this structure (Fig. 2, D and D'). From this analysis, we conclude that a subset of cells destined to form the renal papilla quiesces at E11.25 or shortly thereafter. Thus, cells of the renal papilla may represent the first terminally differentiated cells of the developing kidney, either exiting the cell cycle entirely, or dramatically slowing their proliferation at E11.25, immediately following the onset of nephrogenesis. Recent gene inactivation studies of Wnt7b showed by morphological criteria that the medulla of the kidney arises at approximately E15.5 (18). Our BrdU-labeling studies indicate that cells destined to contribute to this compartment exit the cell cycle on a continual basis already at E11.25, suggesting that this anatomical structure may develop earlier than previously thought.

Fig. 2.

Short-term BrdU retention in the developing kidney. BrdU incorporation is detected by immunohistochemical staining (dark brown nuclei). To visualize tissue morphology, sections have been lightly counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). A: scheme of BrdU pulsing and harvest. B: 12 h after pulse, the majority of cells of the developing kidney (outlined) are BrdU labeled, demonstrating the highly proliferative nature of the tissue. C: 3 days after the BrdU pulse, the majority of cells are BrdU negative, with BrdU-positive cells concentrated to the capsule and the nascent papilla (C'). Six days after pulse, little BrdU labeling is seen in the kidney, with the exception of cells of the kidney capsule, and the nascent papilla (D', arrows). C, capsule; MM, metanephric mesenchyme; NZ, nephrogenic zone; RC, renal calyx; U, ureter; UB, ureteric bud.

The papilla of the kidney is composed of collecting ducts, loops of Henle, vasculature, and interstitial stromal cells. To understand whether a specific cell type within the papilla is responsible for BrdU retention, we stained adjacent sections of kidneys from mice administered BrdU at E11.5 with either anti-BrdU antibody or with the collecting duct marker DBA lectin (Fig. 3). As previously reported, BrdU-retaining cells can be found both in the interstitium and in tubular epithelium (11). Within tubular epithelia, cells are located both within DBA lectin-stained cells of the collecting duct lineage, and within non-DBA-stained presumptive loops of Henle. Nephron and collecting duct cell lineages are distinct (12, 19), and this marker analysis demonstrates that cells from both of these compartments quiesce early in development.

Fig. 3.

Localization of BrdU-retaining cells by staining with the collecting duct marker DBA lectin. Papillas were harvested from 3-mo-old animals administered BrdU at E11.5. Adjacent sections were stained for DBA lectin (A) or BrdU (B). Enlargements of boxed areas are shown in A' and B'. A and A': DBA-lectin stained cells (brown) can be seen lining collecting duct tubules of the papilla, as well as the RC. B and B': outline of DBA-stained cells is shown in yellow. Nuclear BrdU staining (dark brown) can be seen in nuclei of collecting duct cells (solid arrows), DBA-negative presumptive loops of Henle (open arrowheads), and presumptive interstitial cells that are not directly associated with tubule lumena (solid arrowheads). P, proximal papilla; D, distal papilla.

To understand why the quiescent population of cells within the renal papilla is not diluted out during postnatal growth of the organ, we performed a series of BrdU pulse chase experiments during the period of extensive organ growth from P7 to P28 (Fig. 4). The objective of these experiments was to gain insight into the degree of cellular proliferation in distinct regions of the growing juvenile kidney and to understand whether BrdU-retaining cells sequestered within the papilla during kidney development might remain quiescent due to limited growth of that tissue compartment. Mice were harvested at P14, P21, or P28 following daily BrdU pulsing for 1 wk before death (Fig. 4A). Nuclear BrdU incorporation was visualized by immunohistochemistry of kidney sections. Staining was quantified in equivalent surface areas of cortex, outer medulla, and papilla from three distinct animals per time point, the latter to understand whether there was significant individual variation. Overall, there is a trend of decreasing proliferation with age, and standard deviation from the mean shows an acceptable degree of individual variation for interpretation of the study (Fig. 4B). The cortex and outer medulla both display extensive BrdU incorporation, demonstrating that these regions undergo vigorous expansion by proliferation during juvenile growth of the organ (Fig. 4, B and C). Interestingly, proliferation within the kidney papilla is extremely rare at all three time points analyzed (Fig. 4, B and C). From this analysis, we conclude that the papilla displays minimal growth through cellular proliferation compared with other regions of the kidney from P7 onward. This is consistent with results of single overnight BrdU-labeling experiments showing that proliferation within the epithelium of the loop of Henle of the rat is negligible during the first 2 wk following birth (1). Rather than growing through intrinsic cell proliferation, the papilla thus appears to grow primarily by tubule elongation in the corticomedullary zone in the postnatal period (1). Having concluded that growth of the entire papilla through proliferation is highly restricted from P7 onward, we wanted to test whether growth through proliferation was also restricted in the perinatal period. We performed a labeling experiment in which BrdU was administered at E17.25, and kidneys were harvested at E17.5, P3, and P28 (Fig. 5). We find that there is very little labeling of cells in the distal papilla, whereas numerous labeled cells can be found more proximally in this region, demonstrating a regional restriction of proliferation within the papilla in the perinatal period. We conclude that distal regions of the papilla have already matured at E17.25 in the mouse, indicating that the papilla matures in a distal-to-proximal manner.

Fig. 4.

Papilla represents a cell compartment within the juvenile kidney with very limited turnover. A: BrdU dosing and organ harvest scheme. Three individual animals were dosed and harvested per time point. B: quantification of BrdU-stained nuclei in equivalent areas of tissue from cortex, outer medulla, and papilla reveals that cellular proliferation in the papilla is extremely rare compared with other regions of the kidney. Sections from 3 separate individuals were analyzed, and error bars in the graph represent the standard deviation of measurements. C: representative sections from BrdU-stained cortex, outer medulla, and papilla showing widespread distribution of proliferating cells in cortex and outer medulla, and a paucity of proliferating cells in the papilla.

Fig. 5.

BrdU administered at E17.25 shows limited incorporation in the distal papilla. After administration of a single pulse of BrdU at E17.25, kidney papillas were stained for BrdU retention at E17.5, P3, and P28. At all 3 times of harvest, little BrdU retention can be seen in the distal papilla (square bracket).

Based on these findings, we predicted that BrdU administration early in kidney development would lead to deposition of BrdU-retaining cells at the tip, whereas administration late in maturation of the papilla would lead to deposition at the base. To test this model, we compared the localization of BrdU-retaining cells at 3 mo after administration of BrdU at either E11.5, E14.5, or P2 (Fig. 6). Indeed, we find that BrdU retention is biased toward the distal papilla on BrdU administration in early development and toward the corticomedullary junction late in development (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Localization of BrdU-retaining cells within the papilla following administration at time points during papilla development and growth. BrdU was administered at either E11.5, E14.5, or P2, and papillas were harvested for analysis at 3 mo of age. Staining of serial papilla sections reveals that the majority of BrdU-retaining cells from the E11.5 administration are located within the distal papilla, whereas the majority of retaining cells from the P2 administration can be found in the proximal papilla. Administration at E14.5 results in distribution of retaining cells throughout the papilla.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we find that labeling of BrdU-retaining papilla cells is limited to time points during development and growth of the kidney papilla. Between E11.5 and P3, significant numbers of cells continually exit the cell cycle and become localized to both the interstitium and tubular epithelium of the papilla. The papilla grows through proliferation in a distal-to-proximal manner, with cellular proliferation arresting in the distal region before E17.5, a time at which very extensive proliferative growth is seen in the rest of the kidney. Interestingly, we find that BrdU-retaining cells destined for deposition in the papilla can be labeled already at E11.5, several days before establishment of a morphologically distinct kidney medulla at E15.5. We propose that BrdU retention occurs through regionalized maturation of the papilla surprisingly early in development, with cells slowing and exiting the cell cycle in a distal-to-proximal manner throughout the E11.5 to P7 period.

The biological significance of the long-term BrdU-retaining population in the renal papilla is unclear. On the one hand, these cells simply represent the first cells to terminally differentiate during kidney development and are the earliest cells to contribute to mature structures within the organ. It also remains a possibility that, due to their early exit from the cell cycle, these cells undergo fewer divisions than other nephron epithelial cells of the kidney and may therefore retain greater potential for reparative proliferation following injury. In the reparative response to acute injury, genetic lineage studies conclusively demonstrated that the origin of new nephron epithelial cells is surviving nephron epithelium and that contribution of interstitial cells is negligible (7), with bone marrow-derived cells making a variable but small contribution (3, 4, 10, 17). In acute injury, epithelial cells of the distal (S3) segment of the proximal tubule are lost, and surviving S3 epithelial cells dedifferentiate and repopulate the damaged section (7, 14–16). There appears to be a bias toward proliferation of distal sections of the S3 segment in severe injury (5), possibly because few cells survive in the more proximal sections. Proliferation of tubular epithelial cells in the papilla in response to acute injury has been reported (11), suggesting that BrdU-retaining cells of the papilla may participate in the repair of nephron epithelia following severe acute injury in which the majority of S3 epithelial cells are lost. Further studies employing lineage-marked cells will be required to clarify the degree of contribution of BrdU-retaining tubular epithelium of the papilla to nephron repair.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources 2P20RR18789-06 (project 1, L. Oxburgh) and a Norman S. Coplon extramural grant from Satellite Healthcare (L. Oxburgh). Additional support was provided by Maine Medical Center Research Institute core facilities for Histopathology (supported by 2P20RR18789-06) and the Maine Medical Center Animal Facility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express thanks to B. Larman for insightful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cha JH, Kim YH, Jung JY, Han KH, Madsen KM, Kim J. Cell proliferation in the loop of Henle in the developing rat kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1410–1421, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotsarelis G, Cheng SZ, Dong G, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Existence of slow-cycling limbal epithelial basal cells that can be preferentially stimulated to proliferate: implications on epithelial stem cells. Cell 57: 201–209, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duffield JS, Park KM, Hsiao LL, Kelley VR, Scadden DT, Ichimura T, Bonventre JV. Restoration of tubular epithelial cells during repair of the postischemic kidney occurs independently of bone marrow-derived stem cells. J Clin Invest 115: 1743–1755, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang TC, Alison MR, Cook HT, Jeffery R, Wright NA, Poulsom R. Proliferation of bone marrow-derived cells contributes to regeneration after folic acid-induced acute tubular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1723–1732, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujigaki Y, Goto T, Sakakima M, Fukasawa H, Miyaji T, Yamamoto T, Hishida A. Kinetics and characterization of initially regenerating proximal tubules in S3 segment in response to various degrees of acute tubular injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 41–50, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartman HA, Lai HL, Patterson LT. Cessation of renal morphogenesis in mice. Dev Biol 310: 379–387, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphreys BD, Valerius MT, Kobayashi A, Mugford JW, Soeung S, Duffield JS, McMahon AP, Bonventre JV. Intrinsic epithelial cells repair the kidney after injury. Cell Stem Cell 2: 284–291, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansson CB, Momma S, Clarke DL, Risling M, Lendahl U, Frisen J. Identification of a neural stem cell in the adult mammalian central nervous system. Cell 96: 25–34, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavker RM, Sun TT. Epidermal stem cells: properties, markers, and location. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 13473–13475, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin F, Moran A, Igarashi P. Intrarenal cells, not bone marrow-derived cells, are the major source for regeneration in postischemic kidney. J Clin Invest 115: 1756–1764, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliver JA, Maarouf O, Cheema FH, Martens TP, Al-Awqati Q. The renal papilla is a niche for adult kidney stem cells. J Clin Invest 114: 795–804, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oxburgh L, Chu GC, Michael SK, Robertson EJ. TGFb superfamily signals are required for morphogenesis of the kidney mesenchyme progenitor population. Development 131: 4593–4605, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxburgh L, Robertson EJ. Dynamic regulation of Smad expression during mesenchyme to epithelium transition in the metanephric kidney. Mech Dev 112: 207–211, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogetseder A, Palan T, Bacic D, Kaissling B, Le Hir M. Proximal tubular epithelial cells are generated by division of differentiated cells in the healthy kidney. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C807–C813, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogetseder A, Picard N, Gaspert A, Walch M, Kaissling B, Le Hir M. Proliferation capacity of the renal proximal tubule involves the bulk of differentiated epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C22–C28, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witzgall R, Brown D, Schwarz C, Bonventre JV. Localization of proliferating cell nuclear antigen, vimentin, c-Fos, and clusterin in the postischemic kidney. Evidence for a heterogenous genetic response among nephron segments, and a large pool of mitotically active and dedifferentiated cells. J Clin Invest 93: 2175–2188, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yen TH, Alison MR, Cook HT, Jeffery R, Otto WR, Wright NA, Poulsom R. The cellular origin and proliferative status of regenerating renal parenchyma after mercuric chloride damage and erythropoietin treatment. Cell Prolif 40: 143–156, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu J, Carroll TJ, Rajagopal J, Kobayashi A, Ren Q, McMahon AP. A Wnt7b-dependent pathway regulates the orientation of epithelial cell division and establishes the cortico-medullary axis of the mammalian kidney. Development 136: 161–171, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J, Carroll TJ, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal cells in the mouse metanephric kidney. Development 129: 5301–5312, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.